A picture held us captive*: secular narratives and the Christian mission

advertisement

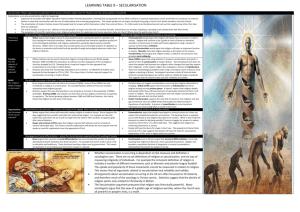

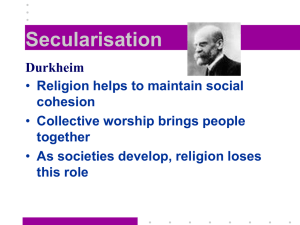

‘A picture held us captive’: secular narratives and the Christian mission Dominic Erdozain King’s College London dominic.erdozain@kcl.ac.uk • • • • • Power of discourse Three kinds of secularisation theory Bowing to secularisation: the Liberal tradition Pastoral implications ‘Cause is not what it used to be’: challenges to secularisation theory • ‘Awkward facts’: the uses of history • Conclusion L. Wittgenstein: 'A picture held us captive. And we could not get outside it, for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us inexorably.' Philosophical Investigations (1953) Alice Marguerite Crary and Rupert J. Read, The New Wittgenstein (Routledge, 2000), 232. Reinhold Niebuhr on the power of implicit dogma: ‘all the more potent in colouring opinion because it is not known as a dogma.’ ‘Let Liberal Churches Stop Fooling Themselves’ Christian Century, March 25, 1931 ‘Ecclesiastical pathology, one of the favourite studies of the time’. The symptom was a perpetual pulse-taking at the behest of ‘empiricists within and without the churches’ – an obsessive compulsion on a corporate scale. The writer believed that ‘churches would gain by intermitting for, say three years, the whole series of statistical returns, and simply going on with duty’. British Weekly, 27 July 1888, 213. • Three kinds of secularisation theory: • Idealist – ideas drive history, make belief untenable; religion is the ‘dark’ past eg. Peter Gay,. The Enlightenment: The Rise of Modern Paganism (Vol. 1). W. W. Norton & Company, 1995. • Materialist / sociological – economics, industrial organisation problematise religion and religious ‘community’ eg. Peter L. Berger,. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Anchor Books, 1990. ‘[By] the twenty-first century, religious believers are likely to be found only in small sects, huddled together to resist a worldwide secular culture.’ Peter Berger, The New York Times, 1968 • Cultural – cultural change eviscerates religious values Eg. Callum G. Brown, The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation 18002000. London: Routledge, 2000. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Tegel Prison Letter April 30 1944 ‘And we cannot be honest unless we recognize that we have to live in the world etsi deus non daretur. And this is just what we do recognize – before God! God himself compels us to recognize it. So our coming of age leads us to a true recognition of our situation before God. God would have us know that we -must live as men who manage our lives without him. The God who is with us is the God who forsakes us (Mark 15:34). The God who lets us live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually. Before God and with God we live without God. God lets himself be pushed out of the world on to the cross. He is weak and powerless in the world, and that is precisely the way, the only way, in which he is with us and helps us.’ Alister E. McGrath, The Christian Theology Reader (Wiley-Blackwell, 2006), 53–4. ‘The teaching of traditional Christians of course makes no appeal to men and women of modern education.’ Bishop Barnes of Birmingham, 1949 Quoted in Adrian Hastings, A History of English Christianity 1920-2000, 4th ed. (London: SCM Press, 2001), 491. David Sheppard [taking over from Robinson as Bishop of Woolwich, 1969]: ‘Bishop John Robinson said he did not think there would be any visible church in the inner-city in ten years’ time! I made a mental note to do everything in my power to prove him wrong.’ Bishop of Southwark, Mervyn Stockwood told him: Congregations ‘are likely to be small’ [Church had to] ‘face the facts’ Sheppard refers to ‘chronic collapse of confidence’ ‘even if it were not true, they acted as if it were’ David Sheppard, Steps Along Hope Street: My Life in Cricket, the Church and the Inner City (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2002), 121. William Temple: on the apparently inexorable rise of the state, and why the church needs to accept it: ‘The process is inevitable; it is not likely to be reversed.’ Quoted in F. K Prochaska, Christianity and Social Service in Modern Britain: The Disinherited Spirit (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 95. ‘Forty years after David Martin wrote A Sociology of English Religion, I asked him to reflect on its predictions. He said he had not anticipated how enthusiastically the churches would collude in their own demise. He had not expected the mainstream churches to jettison so much Christian belief and ritual in the hope that imitating secular culture would make them more attractive. Encouraged by the bright young things who ran television, vicars vied with each other to argue that socialism, communism, feminism (indeed any secular ‘ism’) was really more Christian than Christianity.’ Steve Bruce, ‘Secularisation in the UK and the USA’, in Secularisation in the Christian World: Essays in Honour of Hugh McLeod, ed. Callum G Brown and M. F Snape (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), 207. ‘The idea that a prediction may have influence upon the predicted event is a very old one. Oedipus, in the legend, killed his father whom he had never seen before; and this was the direct result of the prophecy which had caused his father to abandon him. This is why I suggest the name ‘Oedipus effect’ for the influence of the prediction upon the predicted event (or, more generally, for the influence of an item of information upon the situation to which the information refers)’. Karl Raimund Popper, The Poverty of Historicism (Routledge, 2002), 10–11. Terry Eagleton on Dawkins, The God Delusion: ‘It thus comes as no surprise that Dawkins turns out to be an old-fashioned Hegelian when it comes to global politics, believing in a zeitgeist (his own term) involving ever increasing progress, with just the occasional ‘reversal’.’ ‘LRB · Terry Eagleton · Lunging, Flailing, Mispunching’, n.d., http://www.lrb.co.uk/v28/n20/terry-eagleton/lunging-flailing-mispunching ‘The “critique of metaphysics”… turns out to be a new metaphysics’. John Milbank, Theology and Social Theory: Beyond Secular Reason (Basil Blackwell, 1990), 105. Peter Berger: ‘the assumption that we live in a secularised world is false: The world today, with some exceptions…is as furiously religious as it ever was, and in some places more so than ever.’ The Desecularization of the World (1999) Peter Burke: ‘The historian is the guardian of awkward facts, the skeletons in the cupboard of the social memory’. ‘History as Social Memory’, in Memory, History, Culture, and the Mind, ed. T. Butler (Oxford 1989), 110. ‘At least five times, therefore, with the Arian and the Albigensian, with the Humanist sceptic, after Voltaire and after Darwin, the Faith has to all appearance gone to the dogs. In each of these five cases it was the dog that died. How complete was the collapse and how strange the reversal, we can only see in detail in the case nearest to our own time.’ G.K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man (1925)