Presentation - Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

advertisement

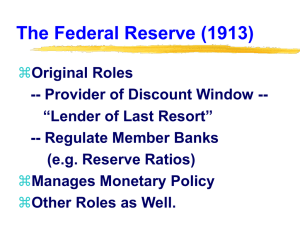

Volatile Times and Persistent Conceptual Errors: U.S. Monetary Policy 1914-1951 Charles W. Calomiris Columbia Business School and NBER Atlanta Fed Jekyll Island Conference November 2010 Central Questions • What did the Fed try to do, why, and how? • What effects did Fed monetary policy have? • Why did it take so long to correct errors in monetary policy? • What do we learn from this experience about how central banks learn? – Importance of initial conditions (beliefs about policy; unique US circumstances required original thinking) – Importance of environment (especially, volatility of WWI, roaring twenties, Great Depression, WWII, which made it hard to identify policy errors) What Did the Fed Try to Do, Why, and How? • Goal: Provide an “elastic” currency, which was expected to resolve problems of peculiar US tendency for banking panics, which was related to unusually high seasonal swings in interest rates (under unit banking, cotton crop, etc.). And do so without centralizing power, without promoting bubbles and without threatening gold standard. NOT expecting (or desiring) to prevent cycles or bank failures. • Why? Historical experience of 1873-1907. Panics occurred at seasonal and cyclical times of high banking system leverage (peaks) when liabilities of failed businesses spiked and stock market fell (Calomiris and Gorton 1991). Stable reserve ratios would reduce systemic liquidity risk. • How: Real bills doctrine, decentralized system of 12 districts (‘til 1935) lending reserves on loans as collateral, balance of power among government, banks, others. Real Bills Doctrine • Provide liquidity to accommodate loan demand variation based on fundamentals (which will allow banks to keep their loan-to-reserves stable, and will thus smooth seasonal and cyclical fluctuations in interest rates). • To do so, focus on lending against “self-liquidating” commercial bills that finance goods in transit. • Avoid fueling bubbles by avoiding accommodation of real estate or stock market lending. => (1) Riefler-Burgess framework’s focus on borrowed reserves and nominal interest rates to gauge needs of market, (2) promote use of real bills as collateral, (3) discourage use of Fed discount window to promote nonreal bills based lending, and (4) lend at a “penalty” rate (real bills limits and penalty rate were abandoned with WWI need to support government). Figure 1 The Loan Market with and without the Fed Loan Supply (without Fed) Real Loan Interest Rate Loan Supply (with Fed) High Loan Demand Average Loan Demand Low Loan Demand Real Quantity of Loans Problems with Real Bills Policy • Accommodates demand shifts for loans assuming that they are based on fundamentals, and is thus pro-cyclical in effect (no nominal anchor) • Focuses on nominal interest rate and does not take account of real interest rate changes due to expected inflation changes. • Does not take into account loan-supply shocks. • The latter two are especially relevant for explaining the monetary implosion of the Great Depression. Figure 2 Loan Supply Contraction and Rising Real Loan Rates During the Depression Loan Supply (1932) Real Loan Interest Rate Loan Supply (1931) Loan Supply (1929) Loan Demand (1929) Loan Demand (1931) Loan Demand (1932) Real Quantity of Loans Why Did It Take So Long To Correct Errors? • Fed didn’t expect to end recessions. • Beliefs about its limited power to spur economy, and misinterpretations of loan and money supply collapses as demand-side collapses. • Money illusion by Fed policy makers. • Volatility of environment: WWI; technology changes in 1920s, alongside deep structural changes in financial sector, transport, communications, stock market boom and bust, and gold standard resumption; Great Depression shocks and New Deal policies; and WW II. This volatility was not conducive to identifying errors in thinking about policy. Priors were not revised. Identifying Policy Influences Is Hard • This statement is true even in retrospect. • Some key issues about the effects of monetary policy during the interwar period remain highly controversial; identifying them and adapting policy in real time was challenging. • To illustrate that point, consider some of the major continuing controversies. – Was 1928-29stock market boom a bubble? (My view: Perhaps not.) – Was the Fed constrained by the gold standard, and if so when and why? (My view: In a few months in late 1931 there were justifiable concerns about the risk of a run on the dollar; otherwise no.) – Were waves of bank failures in 1930 and early 1931 national panics or reflecting fundamental insolvency? (My view: No.) – Was the Fed constrained by a “liquidity trap”? (My view: No.) – Did the Reserve Requirement Increases of 1936-1937 Cause the Recession of 1937-1938? (My view: No.) The Fed’s Success Story: Seasonal Smoothing • Seasonal variation in the level of interest rates and the ratio of loans to reserves became much smoother after the founding of the Fed. • Seasonality of interest rate volatility and stock returns volatility were also reduced. • These findings by Miron and Bernstein et al. suggest that accommodating seasonal demand did reduce seasonal liquidity risk. • It is possible that the observed success in seasonal smoothing reinforced adherence to the Riefler-Burgess framework, and thereby contributed to cyclical policy failures. Politics and the Fed • Changes in policy did not only reflect economic considerations. The Fed was constrained by force majeure. • WWI and WWII: monetary policy independence has limits. • 1935 Act: Consolidation of power at Board, and reduction of power of Fed (also note ESF, silver, targeting of gold price). • The Accord of 1951: reflects expansion of Fed’s balance sheet, which allows it to credibly threaten a contraction. Lessons for Today: (1) Learning Is Slow When You Need It Most • Volatile times can make learning and accountability hard. Likely false views are harder to discredit • Is it obvious that TBTF bailouts were a good idea, and that related policies were appropriate in implementing them? • Is it obvious which parts of TARP/TALF/etc. were properly designed? • Is it obvious whether QE II is now warranted? • If not, even if all these were bad ideas or badly done, policy makers will not learn easily or be held accountable for their errors as much as they should be. Lessons for Today: (2) New Institutions Create, Not Just Resolve, Big Problems • The creation of the Fed was a response to the panic-ridden national banking era. Perhaps a better response would have been branch banking, which would have permitted the creation of a central bank that could have learned from other countries’ histories better. • We solved the problem of seasonal smoothing and disruptive national banking era liquidity risk, but with a mistaken policy approach that gave us the much greater banking and economic distress of the Great Depression. Lessons for Today: (3) What Will Be Political Fallout of Current Reforms • Major political shocks (WWI, the Great Depression, and WWII) matter for monetary policy over and above their economic consequences: all caused major changes in the structure and operations of the Fed, with lasting consequences. • Will Dodd-Frank further politicize the Fed? • What will be the consequences for long-term price stability and regulatory efficiency?