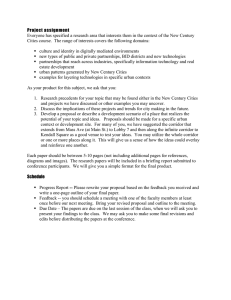

Britain | HS2 HS2 starting to become a reality The core section of Britain’s second high-speed line between London and Birmingham has been progressing at pace. Mark Simmons talks exclusively with HS2 Ltd’s chief rail officer Emma Head about how much work remains before the first trains start running. The Colne Valley Viaduct near west London will become Britain’s longest railway bridge. Photo: HS2 Ltd I T might seem premature to imagine the first trains running when even the company responsible for constructing Britain’s second highspeed line, HS2 Ltd, is quoting a fouryear window for its completion. But rail passengers travelling into Birmingham’s New Street and London’s Marylebone stations already have a very real sense that one of Europe’s biggest construction projects is making tangible progress. They can see for themselves, respectively, the foundations of HS2’s northern terminus of Birmingham Curzon Street taking shape and the elegant Colne Valley viaduct at the southern end of the route near West Ruislip extending itself, concrete segment by concrete segment, for more than 3km over lakes and waterways to form what will become Britain’s longest railway bridge. A total of six tunnel boring machines (TBMs) are currently burrowing their way through a mixture of ground types and tunnelling on HS2 is already estimated to be around 50% complete overall. In total, approximately two-thirds of the budget for civil engineering work between London (Old Oak Common) and Birmingham has now been spent. After several years of uncertainty caused by rising construction costs and political equivocation, culminating last October in the cancellation of all sections of HS2 north of Birmingham, the future for HS2 is now much clearer. Phase 1, 225km between London and Birmingham, with a connection north of Birmingham to the West Coast Main Line at Handsacre (see timeline) is now the only phase that will be built (see panel, p21). The most southerly part of the route, the 13km tunnelled section between the major hub interchange at Old Oak Common in west London and the terminus at Euston in central London, has been paused for at least two years, while the government assesses the viability of attracting private-sector finance to complete this stretch. After the turbulence of recent times, including the departure of CEO, Mr Mark Thurston, last autumn - his replacement is expected to take up their post this summer - and reams of HS2 timeline March 2010 HS2 launches 20 January 2012 Plans approved; project split into two phases February 2017 September 2020 Phase 1 parliamentary Phase 1 construction offically starts approval February 2021 November 2021 Phase 2A parliamentary London Old Oak Common approval station construction starts IRJ May 2024 “My job is to keep an eye on the key decisions to make sure they will come together to deliver an end-state railway and I have the power to instruct change and make better programme decisions where I can see a new scope or a need to alter delivery to make sure we protect that end-state outcome.” High Speed 2 Prime system integrator Source: HS2 Ltd negative media coverage, to attempt to get the project back on track might seem a brave undertaking. Yet this is exactly the challenge that HS2 Ltd’s chief rail officer, Ms Emma Head, accepted when she began work earlier this year. With two decades of civil engineering experience in rail, and a member of HS2 Ltd’s executive team since 2015, Head is just the kind of person the project needs, especially as 11 major contracts are due to be awarded later this year (see table, p22). When she sits down for an exclusive interview with IRJ it is immediately apparent Head has the whole route very clearly imprinted on her mind, as she talks seamlessly about each section without hesitation or recourse to maps or other paperwork. She explains that her role emerged as a direct result of lessons learned from Crossrail, the £18.8bn project to build a new east-west rail tunnel across London, where the first trains began running on what is now the Elizabeth Line in 2022. In the heat of construction, with many contractors on board, it became evident that responsibility for managing certain tasks was unclear. “So HS2 Ltd has mapped all of the interfaces between the construction packages and between the systems where we expect there to be interfaces that need to be managed, and which contractor we believe should be discharging that integration activity,” Head says. What hope for Phase 2? W ITH all sections of Phase 2, including 2A, 2B east and 2B west, now officially cancelled by the current government, it is unclear whether either of the two northern parts of HS2’s original Y-shaped network could still be built at a later date. Head confirms that safeguarding for Phase 2A was removed earlier this year. Despite this withdrawal of protection from other development, it is unlikely that the route will be immediately lost as it remains protected by the Act of Parliament authorising the construction of HS2 that continues in force until 2026. At present, safeguarding remains in place for Phase 2B as some of the line might be required for other new lines in northern England, collectively known as Northern Powerhouse Rail and informally as HS3. With a general election due to held by January 2025, some proponents of HS2 suggest that an incoming government might reverse the decision to cut Phase 2. The leader of the opposition, Sir Keir Starmer, has already said this is not something that his government would do if the Labour Party is elected. However, his shadow transport minister, Ms Louise Haigh, has previously vowed “to get the job done,” suggesting that the prospects of reviving at least part of Phase 2 are not completely dead. The elected mayors of Birmingham and Manchester, Mr Andy Street and Mr Andy Burnham, are working with a private-sector consortium, including Arup, Mace and Arcadis, led by former HS2 Ltd chair Sir David Higgins, to put forward alternatives. These include a lower-speed line that would cost less, and improvements to and or new sections of the West Coast Main Line. A full set of proposals is expected this summer. November 2021 December 2021 March 2023 Phase 2B east curtailed Alstom-Hitachi joint venture wins rolling stock contract London Old Oak Common Euston terminus section paused IRJ May 2024 Head admits that she has already had to make changes surrounding railheads and placeholder assumptions on behalf of systems. “One thing we’ve done which I think is unique in our rail systems contracts is that we’ve specified that HS2 will undertake a role we’ve called prime system integrator, where we’ve identified multi-face interfaces, which are the hardest to integrate and are often critical,” she says. “We will retain accountability for each one and we will actively integrate it, rather than outsourcing it to a supplier. One of things I’m trying to work out now is what are the critical pinch points and not shy away from them.” Head is keen to point out that many October 2023 Phases 2A, 2B west and remainder of 2B east cancelled January 2024 Birmingham Curzon Street station construction starts 21 Britain | HS2 HS2 contracts to be awarded in 2024 Package Value band (£m at 2020-21 prices) Shortlisted bidders Engineering Management System (EMS) 50-100 = Thales Transport & Security = Siemens Mobility Third-Party Communications 50-100 = EE/BT Group = Thales GTS Overhead Catenary System (OCS) 100-250 = Colas Rail =Balfour Beatty Group, ETF and TSO (BBVT joint venture) Washwood Heath Depot and Network 250-500 Integrated Control Centre = Gülermak = Vinci Construction = VolkerFitzpatrick Operational, Telecommunications and 250-500 = Thales Transport & Security SystemsSecurity = Siemens Mobility Tunnel and Lineside 250-500 Mechanical & Electrical = Alstom = Costain Group Track Installation 250-500 = BBVT (Phase 1, Lot 1 Urban) = Colas Rail = Ferrovial Construction/ BAM Nuttall joint venture = Rhomberg Sersa/ Strabag joint venture High-Voltage Power System 250-500 = SMC Rail Power joint venture of Siemens Mobility and Costain = UK Power Networks Services (Contracting) Track Installation 250-500 = BBVT (Phase 1, Lot 3 North) = Colas Rail Ferrovial Construction/ BAM Nuttal JV Track Installation 250-500 = BBVT (Phase 1, Lot 2 Central) = Colas Rail = Ferrovial Construction/ BAM Nuttall joint venture = Rhomberg Sersa/ Strabag joint venture Control, Command & Signalling (CCS) 500-3000 and Traffic Management Source: HS2 Ltd 2028-29 2029-33 2025 Rolling stock First trains ready Phase 1 opens from construction starts for testing London Old Oak Common to Birmingham Curzon Street 22 = Alstom = Hitachi Rail = Siemens Mobility other lessons learned from the construction of Crossrail have been taken on board by HS2 Ltd. These include software integration and performance measurement. For the former, although many software systems are off-the-shelf products, they each have individual update cycles, which can impact on other systems. HS2 has already appointed a head of software, so that assumptions of how software systems will work can be mapped out and monitored in real time. “There are around 200 software systems needed to build HS2, but only 10 are critical,” Head explains. “Without having gone through our initial analysis we wouldn’t necessarily be aware of that, whereas we certainly are now.” Measuring and managing performance should allow HS2 to avoid some of the public relations disasters experienced by Crossrail when key milestones were missed. “I remember speaking with my colleagues at Crossrail when they thought it was 90% complete. Not long after, they told me it was only 68% complete because they realised that things hadn’t been built,” Head says. “So, we’re making sure that we really understand technical debt. And when we proceed to build something, we are clear what is owed to us later.” While Crossrail has certainly proved useful for navigating around potential system integration pitfalls, it does not provide a comprehensive blueprint, as the project involved tunnelling under London and the use of existing infrastructure at either end, therefore avoiding many of the planning issues that HS2 Ltd is contending with in order to build a new railway between London and Birmingham. With a mindboggling 8500 individual planning consents required for Phase 1, Head has her hands full ensuring that planning conditions, especially those around environmental impact and risk, are properly met and construction schedules managed accordingly. As a delivery body, working on behalf the British government via the Department of Transport (DfT), HS2 Ltd has also had to navigate the fallout 2031-35 November 2030 First trains enter service Handsacre spur opens, (on West Coast Main Line first trains to/from if HS2 not yet open) conventional network 20?? Old Oak Common London Euston opens IRJ May 2024 of political decisions, over which it has no control. Head won’t be drawn on how a potential change of government (a general election must take place before January 2025 - see panel, p21) might affect prospects for reinstating those sections of HS2 cancelled by the current administration. Nor will she comment on the ongoing debate over the rising costs of the project (see panel, right) - those are matters for politicians, she insists. The rise and fall and rise of HS2’s costs Preparatory work Head is, however, able to clarify a couple of points that have been widely misunderstood in the British media. One relates to the paused tunnel section to Euston. Reports that tunnelling has already started at Old Oak Common are wide of the mark, she says. To allow progress with extensive surface work at Old Oak Common, the two TBMs that will bore the tunnel will be lowered into their launch chambers later this year. Head says this is part of the preparatory work for the Euston tunnels, which is funded to 2025. Until a decision has been made by DfT on proceeding with construction, the TBMs will remain stationary, effectively buried at Old Oak Common. Head is also able to shed light on potential service levels and routes to be served by the new high-speed train fleet, construction of which is due to start next year (see panel, p24). “We IRJ May 2024 W HEN HS2 was launched in 2010 it was costed at £37.5bn in 2009 prices and included the full route from London Euston to Birmingham Curzon Street (Phase 1), with separate lines continuing to Crewe (Phase 2a), Manchester (Phase 2b west) and Leeds (Phase 2b east). By 2020, as the Covid-19 pandemic hit, the projected cost had rocketed to £106bn. After Phase 2b east was curtailed in 2021, the total costs were estimated at £53-71bn. And when the British government cancelled Phase 2 in its entirety in October 2023 it said it was taking the £36bn saved to redistribute to local transport projects. A report by the Public Accounts Committee of the House of Commons in February described HS2 as “very poor value for money.” HS2 currently expects the project to cost £67bn, including inflation. The PAC notes that the current estimate does not take into account the potential difficulty of raising private finance to complete the Old Oak Common - Euston section. Approximately £2.2bn has been spent on the now-abandoned Phase 2. Although inflation in Britain is currently on a downward trend, it seems inevitable that in the next five years or longer until opening costs will rise further. The question is by how much. 23 Britain | HS2 don’t have a formal set of revised train specifications from DfT yet, but we’ve been given the working assumptions that we can use to mature our design with,” Head says. Direct trains These assumptions are that three 400m trains, each composed of two 200m-long high-speed trains with a total capacity of around 1000 passengers, will run every hour between Old Oak Common and Birmingham Curzon Street. And, when the Handsacre spur is complete, an additional six single 200m trains per hour will run from Old Oak Common directly to destinations north of Birmingham. Suggestions that the 400m trains will split or join at Birmingham are firmly dismissed by Head. “There’s no time benefit to that,” she explains. So, at present, there are not expected to be any direct trains between Birmingham Curzon Street and the north of England and beyond. This means that the line connecting Birmingham and the Handsacre spur (see map, p21) will not be used in regular service. For the trains running through from London to destinations on the conventional network north of Birmingham, HS2 is working with the manufacturers on detailed design issues, such as how to achieve level boarding after the trains leave the HS2 network. “The Network Rail stations that the trains might be able to stop at include platforms that don’t have a consistent height and tracks that don’t have a consistent cant and profile,” Head says. New high-speed trains still on schedule A LSTOM and Hitachi Rail are the 50:50 partners in a joint venture that in December 2021 was confirmed as the winning bidder to supply new trains for HS2. The deal for 54 eight-car high-speed trains, each 200m long, plus 12 years maintenance, was agreed at a price of £1.97bn. Each train will have capacity for 550 passengers and will be configured to run in multiple. Siemens, Talgo and CAF were shortlisted for the contract, with both Siemens and Talgo launching legal challenges during the procurement process. The Talgo case was settled in June 2021, but the Siemens case, started in the same month, went to the High Court, where the challenge was rejected on all six counts in November 2023. Construction of the new fleet was expected to start in 2025 at the time of contract award and, perhaps remarkably, Head says that the original timescale remains in place. The trains will be built in Britain, with the work shared between Alstom’s facilities in Derby (interiors and electrical systems) and Crewe (bogies) and Hitachi Rail’s plant in Newton Aycliffe (carbodies). The whole fleet will be designed to operate on both HS2 (built to the larger mainland European loading gauge) and the conventional rail network north of Birmingham. Head says that a gauge clearance programme is already underway to ensure that the new trains don’t foul station platforms and other structures on the lines that they are expected to use. The first trains are expected to start testing in 2028, with entry into service at least 12 months later. “We found the [single]-step configuration challenging and so we are now looking at a two-step solution, which is able to deploy differently, yet optimises safe use on both networks. That is a change driven by us. I’ve been asked if infrastructure enhancements would work instead, but that means doing it to every station you might stop at, so it’s much better to do it using the rolling stock.” The two-step solution, which has already been implemented in Florida, adds a couple of seconds dwell time at each stop, as the train’s software assesses which step configuration to deploy, but Head is convinced that this is the most viable way of achieving level boarding at all stations. While Head focuses on the myriad of unresolved issues relating to rolling stock, infrastructure and systems, one key question remains: when will the line open for passengers? Perhaps learning again from Crossrail and the Elizabeth Line, which very publicly missed a succession of opening dates, HS2 Ltd hasn’t specified a precise opening date or even tied it down to a specific year. “It will be sometime between 2029 and 2033,” says Head, whose appetite for hard work and solid results suggests that opening will come sooner rather than later. IRJ The V-shaped piers that carry HS2 into Birmingham Curzon Street have been specially designed to maximise space on the ground. Photo: HS2 Ltd 24 IRJ xxxxx 2016 IRJ May 2024 Britain | light rail Coventry’s Very Light Rail project aims for 2025 demonstration The prototype CVLR vehicle is currently housed in its own shed at the Black Country Innovative Manufacturing Organisation’s National Innovation Centre test track at Dudley. Photo: BC Collection The British city of Coventry is on track to open the world’s first Very Light Rail (VLR) demonstration line next year. Mark Simmons finds out more and examines the possibilities that VLR could unlock in urban areas across the globe. T HE British city of Coventry, just 30km away from its betterknown neighbour Birmingham, is famous for its motoring heritage. Having produced the first British car in 1897, the city went on to become a major automotive manufacturing hub and picked up the title of the British Detroit. Those days are long gone for both cities, but Coventry is on the cusp of a new transport revolution. Next year Coventry City Council, working in partnership with regional transport authority Transport for the West Midlands (TfWM), aims to have a working demonstration of the Very Light Rail (VLR) mass transit system it has been pioneering for around a decade. An 800m stretch of mainly double track will run from Warwick Road, close to Coventry station, to Corporation Street, north of the city centre. A single battery-powered demonstrator vehicle (see panel, pxx) will run on the tracks and will carry invited guests, though not fare-paying passengers. IRJ May 2024 As a demonstrator line that will not be open to the public it can avoid the lengthy planning procedures, including obtaining a Transport and Works Act Order, that a fully-fledged light rail system would have to go through, although it will still need planning approval to operate on public roads – an application was submitted in February. The demonstration line will include a segregated cycleway to enable testing to focus on interaction with road vehicles. Real-world conditions The main purpose of the demonstration line, however, is to prove in real-world conditions that Coventry’s recently-patented track system can be installed speedily. The innovative track, developed in partnership with the nearby University of Warwick’s Warwick Manufacturing Group, is designed to be laid in a trench just 300mm deep and with curves as tight as 15m radius (IRJ March p32). The fundamental aim of Coventry VLR (CVLR) has always been to significantly reduce the cost of building an on-street light rail line in a city centre. This is largely due to the need to divert existing utilities, a process rendered unnecessary by the CVLR low-depth trackform. Determining whether the original goal of achieving a construction cost of around £10m per km, compared with £25-100m per km for conventional light rail, will be met will be one of the key outputs of the demonstration project. The CVLR concept originally arose when Coventry realised that it, along with similar towns and cities with a population of 300,000 or less, could simply not afford conventional light rail solutions, even though passenger numbers are high enough to warrant them. Since its inception, CVLR has been funded by the public sector and the current phase of development, costing around £15m from a total 25 Britain | light rail budget of £40m, is being funded by the Department for Transport (DfT). Before construction of the demonstration line can begin, the DfT has asked an independent review panel to assess the project’s viability. “We will provide evidence to the panel that the project is technically sound, can be delivered within the cost envelope that has been set, has an appropriate safety case and that the vehicle and track are fit for purpose,” says Ms Nicola Small, TfWM programme director for VLR, who is hopeful that the project will be approved later this summer, allowing construction of the demonstration line to begin before the end of the year. DfT approval will unlock a £16.5m funding package that will not only build the demonstration line, but also provide other city-centre traffic improvements for Coventry, including the segregated cycleway, which will enhance the journey experience for all types of users, from pedestrians to car drivers. “The next phase of funding also covers the operating cost of the prototype vehicle that we already have and adapting it to run in a live environment,” Small says. “We’ll be focusing on areas like crashworthiness, to make sure that it can safely withstand getting hit by a bus or a car.” With procurement of an operator for the demonstration line already underway, and assuming that the timetable outlined above runs to plan, test running could start in 2025. “this is our opportunity to make sure that future iterations of the vehicle meet public needs and to showcase it to other cities that might be interested, as well as potential privatesector investors” Small says. The accurate data that the demonstration line will provide will help to build future business cases not only for Coventry but also for other similar-sized cities. Completion of the line will release a final £8.5m of the current budget that will allow the compilation of an outline business case for the first full-scale route in Coventry, as well as the start of work to build a digital twin of the next-generation CVLR vehicle. The long-term aspiration for Coventry is for four CVLR lines radiating from the city centre in a four-leaf clover configuration – see map, right. The first route to be built would likely connect the city centre with University Hospital Coventry and Warwickshire, and ultimately a park and ride site at Ansty, in two phases. This line, that has Autonomous running: when, not if A T present the CVLR vehicle is controlled by a driver in the same way as most conventional light rail vehicles. But those involved in urban planning suggest that the most efficient way of running relatively small rail vehicles in urban areas is by using autonomous control technology. Engineers involved in CVLR say that producing autonomous vehicles is “straightforward.” Small agrees, though she points out that the law has yet to catch up. “Technically, I think that’s a fair statement,” she says. “Autonomy has been developed by the private sector and, in theory, it should be possible to install it in a rail vehicle that has only longitudinal movements. But, legislatively, it is far from straightforward, as there is currently no legislation to support autonomous operation of an urban rail vehicle.” She suggests that issues such as insurance risk pose a big challenge and while the CVLR has flagged the key points that need to be addressed with the DfT, responsibility for changing the law to allow autonomous operation is something that ultimately rests with government. However, Small reveals that although current CVLR plans initially involve vehicles with drivers, feasibility work for Coventry’s first full-scale route includes the use of driverless vehicles. “We assumed that by 2035, we’d be upgrading our fleet to be autonomous and operating it in that way from then,” she says. “That’s based on when we think there might be legislation in place to support it.” Small adds that there are sound economic reasons for pursuing a driverless future. Projections for CVLR show that revenue can triple following its introduction. “It is something that needs to be taken forward if we’re going to be able to achieve viable commercial cases for smaller cities,” she says. “Autonomy needs to be Although CVLR vehicles will initially feature drivers, autonomous operation is planned. Photo: BC Collection factored in.” 26 already been costed at around £189m, would require 20 next-generation vehicles. Small suggests that an outline funding case for this route could be submitted for the next public-sector funding round in 2027, offering the possibility of the first CVLR vehicles running in passenger service before the end of the decade. “ We’ll be focusing on areas like crashworthiness, to make sure that it can safely withstand getting hit by a bus or a car. Nicola Small The timetable for this first line could be accelerated if a private-sector partner decides to invest in the project. Small says that Coventry has already held preliminary discussions with potential candidates. “But we always get to the point that we need to build a demonstrator, because every conversation we have had leads to that conclusion,” she says. “They think it’s a cracking idea, but at this stage it’s still an idea and they want to see a proof of concept they can invest in, as they’ve already acknowledged it has global potential. So we’re confident that the city-centre demonstrator can attract private sector investment.” CVLR’s global appeal could be substantial. Because the patented track form is compatible with standard light rail track, VLR vehicles could run through to destinations on existing conventional light rail networks. Even more intriguing is the possibility that conventional light rail vehicles could run on VLR track, providing a considerably less expensive alternative for extending existing light rail networks. A steady stream of visitors has been heading to see the CVLR in test operation at the National Innovation Centre (NIC) in Dudley, with recent domestic interest coming from London, Oxford, Portsmouth and West Yorkshire. Delegations from further afield include parties from Canada and Thailand. “I’m sure we’ll continue to get plenty of interest,” Small says. “But I think seeing is believing, isn’t it? And that’s why we’ve just got to deliver this demonstrator.” IRJ IRJ May 2024 CVLR’s battery vehicle prototype C VLR’s prototype lightweight battery vehicle, owned by Coventry City Council, was completed by Transport Design International in 2022 and was moved to the Black Country Innovative Manufacturing Organisation’s National Innovation Centre test track at Dudley, where it is housed in its own building. The vehicle body panels are made from lightweight composites so the total mass per linear metre is just over 1 tonne. Unladen, the 11m-long vehicle weighs around 11 tonnes and when fully loaded weighs 16 tonnes, resulting in an axleload of 4 tonnes for the twin-bogie design. The vehicle is 3.17m high, 2.65m wide and can carry 70 passengers with 20 seated. The prototype, designed for a service life of 20 years, has a maximum speed of 70km/h and can traverse gradients of up to 5%. All axles are driven by a 750V 54kWh lithium titanate underfloor battery, delivering a continuous power rating of 175kW. Its range between charges is around 35km, though this varies considerably according to temperature, load, and other factors. The battery can be charged overnight from a 20kW shore supply and, during the day, receive rapid charges taking 3 min 30 sec from a 200kW supply, as well as being charged during regenerative braking. This year the vehicle has been undertaking load and wheel wear tests at the Dudley test track. The prototype CVLR vehicle undergoing wheel wear testing on the Dudley test track balloon loop in March 2024. The bogies are normally covered by protective skirts. Photo: Phil Marsh IRJ May 2024 Riding the CVLR prototype vehicle I RJ was invited to sample the CVLR prototype in March 2024 on the test track at the Black Country Innovative Manufacturing Organisation’s National Innovation Centre in Dudley. The wide 900mm doorway made accessing the vehicle easy and the interior felt spacious, even when all seats were occupied. The ride was exceptionally smooth, even around the 15m balloon loop, when not even the slightest steel-onsteel squeal normally associated with traversing tight curves was audible. The vehicle easily reached a speed of 40km/h and felt stable at all speeds. Although its maximum service speed is 70km/h, it will be limited to 32km/h when in operation on the Coventry demonstrator line, the maximum speed for all vehicles in the city centre. Visibility is good throughout the vehicle and the public address system worked well, with announcements easy to hear. The overall feel was of a high-quality product, matching any current conventional light rail vehicle. 27 Freight | Asia Developing the Middle Corridor for regional economic growth While the Middle Corridor through Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and Georgia has been receiving increased attention as an alternative route for containers moving between China and Europe, a recent World Bank report highlights the potential of developing it as a regional economic corridor. Robert Preston reports. D UE to its many border crossings, the need to transfer containers from rail to ship and road and between track different gauges, as well as other operating inefficiencies, the Middle Corridor has traditionally enjoyed less favour for moving longdistance freight between China and Europe. Also known as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, the Middle Corridor is defined by the World Bank as running from the border crossings between China and Kazakhstan at Dostyk and Khorgos and then across Kazakhstan by rail to the port of Aktau on the Caspian Sea. Consignments then move by sea to Baku, and by rail again through Azerbaijan and Georgia, and either continue to Europe by rail via Turkey or across the Black Sea. Due to what the World Bank describes as inefficiencies and infrastructure gaps in Turkey, the Black Sea route is currently preferred. Despite being the shortest route between the Pacific coast of China and Europe, transit times on the Middle Corridor are three times longer than the northern route via Russia, according to a World Bank report published in November 2023, and are comparable with the maritime route via Singapore and the Suez Canal. However, the attractiveness of both of these routes has declined following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and, more recently, 28 Kazakhstan Railways (KTZ) is the Middle Corridor’s largest railway company. Photo: David Gubler due to the security crisis in the Red Sea that has seen shipping diverted via the Cape of Good Hope. The Middle Corridor remains the least vulnerable route between China and Europe in terms of external shocks. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, container traffic on the Middle Corridor increased by 33% in 2022 when compared with 2021. But as shippers moved unprecedented volumes of traffic to the corridor in the immediate aftermath of the invasion, its limits quickly became apparent. While technical operational capacity was not reached, difficulties at border crossings and with transhipment and coordination led to very lengthy delays. Traffic moved back to alternative corridors with the result that container traffic fell by 37% in the first eight months of 2023 when compared with 2022. Three country focus Despite the current focus on providing an alternative overland route between China and Europe, the World Bank study says that the Middle Corridor primarily provides an opportunity to diversify trade routes and improve connectivity between Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kazakhstan, and accordingly focuses on these three countries. It notes that all three at present rely heavily on Russia to provide access to ports served by global trade routes and as a trading partner, with 39% of imports to Kazakhstan coming from Russia. As well as diversifying imports and reducing dependence on Russia and China, a well-functioning Middle Corridor offers the potential to export more to Europe and reach new markets that could include the Middle East, North Africa, south and southeast Asia. The report sets out the policies and investment required to triple freight traffic and halve transit times by 2030. With these in place, it forecasts that a total of 11 million tonnes of freight will move along the Middle Corridor and via the Caspian Sea in 2030, an increase of 209% on 2021. Of this, 4.4 million tonnes will be transit traffic moving in containers, up by 303%. Although trade from Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kazakhstan is forecast to grow by 169%, at 7 million tonnes it will represent a larger proportion of the total. The World Bank believes that the Middle Corridor will remain a minor player in handling intercontinental trade between China and Europe due to the availability of other options, especially deep-sea shipping. In contrast, at the regional level, developing the corridor and diversifying flows will favour high value-added commodities such as fertiliser, where traffic is forecast to nearly double, as well finished metals, prepared foodstuffs, machinery and chemicals. Time-sensitive and other IRJ May 2024 higher-value freight will partially shift from the northern route to Europe via Russia, and the proportion of Middle Corridor traffic made up by raw materials will fall from 60% to 53%. The World Bank says that the assessment undertaken for its study corroborated a stakeholder survey which found that transport costs on the Middle Corridor were high and, more importantly, unstable. While the cost fluctuates, it is close to the fixed rate of the alternative northern route, even though the transit time is twice as long on the Middle Corridor. The study says that in 2022 it took an average of 50-53 days to move freight from Dostyk or Khorgos via the Middle Corridor to the Black Sea port of Constanta in Romania. Although the longest delays occur during sea crossings, mainly due to a shortage of vessels, the key issues affecting the rail component of the Middle Corridor are high prices, unpredictable transit times, the lack of tracking systems, the difficulties of transhipment and last-mile delivery, and the poor quality of both rolling stock and logistics terminals. End-toend rail infrastructure comes third in the list of the five main factors limiting capacity and causing operational bottlenecks on the Middle Corridor (see panel, above right), ranked in order of time cost. The study says that rail operations “suffer from localised constraints at the port-rail interfaces where a lack of equipment, poor connections, and inefficient operational practices cause delays and increase costs.” Examining the rail component of the Middle Corridor in more detail, the report notes that Kazakhstan Railways (KTZ), Azerbaijan Railways (ADY) and Georgian Railway (GR) are highly interoperable, sharing a common track gauge of 1520mm as well as operational and cultural characteristics inherited from the Soviet era that allow the movement of rolling stock between the different networks. Although the positive impact of this interoperability is reduced by the need to tranship freight at the Caspian Sea ports, some wagons travel across the Caspian Sea by train ferry. Containers move on flat wagons that are interoperable across the different railways, offering opportunities for the acquisition of common fleets that can be shared. Modernisation To meet its full potential, the rail component of the Middle Corridor requires modernisation and investment to relieve localised capacity constraints caused by equipment, infrastructure and operating practices. These cause bottlenecks that cancel out efficient movement over the rest of the corridor. The physical pinch points are mainly located where freight is transhipped or handed over to a different operator. While containers are relatively standardised, the report says that KTZ, ADY and GR still need to fully adopt equipment and operating procedures for the efficient movement of containers throughout the Middle Corridor. This is being prevented by shortages of specialised wagons, cranes and other equipment, such as those needed to handle 20ft containers rather than the 40ft boxes that are the norm in the corridor. The report says that 20ft containers sit idle at most interchange points due to the lack of specialised equipment, putting the Middle Corridor at a competitive disadvantage. Without improvement, current Capacity limitations in order of time cost 1. lack of corridor-wide coordination and management 2. poor operational efficiency of ports and Caspian Sea shipping services 3. lack of end-to-end rail infrastructure 4. delays at border crossing points, and 5. lack of integrated IT systems for data and information exchange. railway infrastructure could be an impediment to further development of the Middle Corridor. Capacity varies widely along the corridor; the northsouth lines tend to have substantially more capacity than the east-west routes, a legacy of the Soviet era. Since the ability of the corridor to perform well is determined by the sections with the lowest capacity, the report says that KTZ, ADY and GR must focus on a well-designed and coordinated plan to increase total corridor capacity. The report identifies the key issues limiting capacity on the most critical sections of the Middle Corridor (see table, p30). In the meantime, “quick wins” could be delivered by ensuring the availability of rolling stock and improving shunting operations in Kazakhstan. Limited availability of rolling stock is a particular constraint in Azerbaijan and Georgia, where transhipment from rail to maritime and road transport also requires immediate attention. In the longer term, the report says that the introduction of automatic block signalling, other signalling modernisation work and the acquisition of new locomotives and flat wagons can lead to large efficiency gains across the three railway networks of the Middle Corridor. Priority projects that must be Middle Corridor Standard gauge 1520mm gauge A Akhalkalaki B Gardabani UKRAINE RUSSIA GEORGIA Cmbdl!Tfb Pati Batumi Istanbul 22 Cetinkaya 5 SYRIA Beyneu Dbtqjbo !Tfb Aktau 30 Tbilisi 10 AB 23 ARMENIA TURKEY Mersin 10 IRAQ Seyfullin Shalkarand 10 60 8 Saksaulskaya 74 Mojynty Aktogai 18 15 Dostyk 74 Zhetigen 17 Shu 77 Khorgos 40 Almaty KYRGYZSTAN N CHINA KAZAKHSTAN 16 18 UZBEKISTAN Baku Arys TURMENISTAN AZERBAIJAN 14 0 km 500 TAJIKISTAN IRAN IRJ Numbers indicate capacity of section of line in total number of trains per day. IRJ May 2024 29 Freight | Asia studied further in Kazakhstan include increasing capacity on the Dostyk Mojynty section, building the Almaty bypass, and rebuilding the Arys Saksaulskaya, Beineu - Mangistau and Seyfullin - Saksaulskaya - Shalkarand sections. In Azerbaijan, work should be undertaken to finalise the implementation of rebuilding the section from Baku to the Georgian border, including replacing signalling and telecommunications systems, raising the maximum speed and changing the overhead electrification system from dc to ac. Finalising the reconstruction of the Tibilisi Akhalkalaki section should be a priority Key Middle Corridor capacity constraints Country Section Estimated capacity, trains per day (pairs) Current usage, % Notes Kazakhstan Dostyk - Mojynty 18 80 Capacity limits exceeded. Line is part of the northern route via Russia and Belarus and also a major artery for exporting commodities from Kazakhstan to China. Kazakhstan Seyfullin Saksaulskaya 10 70 Single-track non-electrified line with over 50% of trains carrying ore and metals. Potential to accommodate an additional one or two at a speed just above 10km/h. Kazakhstan Khorgos - Arys 17 - 77 17 - 40 Non-electrified single-track Zhetigen - Almaty section operating at full capacity of 24 train pairs. Double-track electrified line west from Almaty is a key constraint as all freight trains pass through the city centre and locomotives must be changed from diesel to electric. Usage exceeds 70% on the Shu - Arys section due to 35 pairs of passenger trains and Kazakhstan Uzbekistan freight. Kazakhstan Shalkarand Aktau 8 - 80 8 - 60 Section carries low traffic and not considered a bottleneck, but key issues are low train speeds, locomotive shortages and steep gradients on Beineu - Mangistau section. Trains must be split in two when moving east, causing wagons to build up at Mangistau and the port of Aktau. Azerbaijan Alat - Georgian border 25 80 High wear on the catenary and poor track condition on this double-track line limit capacity. ADY plans to install new overhead electrification equipment in 2024 and increase capacity to 53 trains a day. Gardabani border crossing congested due to a lack of locomotives and average crossing time is three days. Georgia Azerbaijan border - Poti/ Batumi 30 70 Capacity to the Black Sea port of Poti is limited by a lack of locomotives. The branch to Batumi can only accommodate seven trains a day and over 85% of containers arrive at the port by road. 30 in Georgia along with starting work to rebuild the line from Akhalkalaki to Kars in Turkey. There are four border crossings along the Middle Corridor, which vary greatly in operational performance, infrastructure and equipment, as well as the specific issues that affect the speed and predictability of freight services. The border crossings at the break of gauge between China (1435mm) and Kazakhstan (1520mm) at Dostyk and Khorgos are the most developed, with facilities for handling intermodal traffic, but there are disparities between westbound and eastbound traffic throughput. The World Bank report says that from the Chinese side, a very large number of westbound trains are allowed through without delay, while eastbound trains are limited to between six and 10 trains a day at Dostyk. Border crossings The border crossing at Dostyk has a throughput capacity of 18 pairs of trains a day. As this barely meets current demand, the report says that expansion will be required as the Middle Corridor develops. The key issue is the waiting time at the border which can be as long as 60 hours, due in part to an insufficient number of sorting tracks and the lack of an automated and unified system for providing preliminary notification of train arrival times. There is also inefficient management of shunting locomotives and the distribution of wagons across the sorting tracks and transhipment areas. Similar problems have been identified at Khorgos. Although infrastructure is more developed on the Kazakhstan side of the border, there are only two tracks in the transhipment area on the Chinese side which prevents trains from passing each other. Throughput capacity is 17-18 trains a day and the transit time is roughly the same as at Dostyk. There is no marshalling yard and an insufficient number of reception and dispatch tracks, as well as those for storing empty wagons. Rolling stock flow management is inefficient and there is a lack of electronic data exchange. The construction of a marshalling yard or a container terminal should be studied further as a priority, the World Bank says. The busiest border crossing on the Middle Corridor is between Böyük Kasik in Azerbaijan and Gardabani in Georgia, but infrastructure here is weaker than at Khorgos or Dostyk and it forms a major bottleneck. The average crossing time is three days, with IRJ May 2024 capacity limitations and a shortage of locomotives exacerbated by the lack of electronic data exchange for completing customs formalities. Neither Böyük Kasik nor Gardabani were designed as border stations and lack facilities for sorting or reforming trains, while their location in populated areas limits the scope for future development. There are more tracks at Böyük Kasik than at Gardabani, with the result that trains may take longer to cross the border if they are required to undergo customs inspection in Georgia. The border crossing at Akhalkalaki in Georgia opened in 2017, and its modern design and equipment allow for efficient transhipment between 1520mm gauge and the 1435mm-gauge network in Turkey. However, the report says that this border crossing may become a bottleneck following the completion of the new line to Sivas in Turkey. It recommends that further studies to increase capacity here should be undertaken as a priority. Funding partners Although the World Bank says that massive efficiency improvements can be achieved in the short term through better coordination, logistics, and digitisation, it says that large-scale investment will also be needed over the next 10 years and that KTZ, ADY and GR will need publicsector support for the necessary capital spending. While all three generate respectable freight revenue, the report says, past debt obligations and unfunded government requirements prevent them from being able to meet the cost of infrastructure projects. Five key messages of World Bank report 1 Reimagine the Middle Corridor as an economic corridor. Adopt an institutional mechanism that transcends national boundaries and is empowered to develop, promote and maximise use of the corridor as an integrated trade route and economic region. 2 Offer corridor-length logistics solutions. Offer end-to-end standards of service and tariffs, as opposed to the fragmented practices that are in place today. 3 Reform and simplify processes and procedures. Form a strong partnership with an international container operator to take charge of container operations and provide better coordination between border agencies and especially customs authorities to simplify processing goods in transit. Coordination is particularly important between the railways of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kazakhstan. 4 Leverage the potential of digital data flows. Digitise corridor processes and make use of digital data flows to ensure speedy and accurate sharing of information between operators and shippers. 5 Continue to improve infrastructure and equipment along the corridor following a robust prioritisation process. Certain elements of the capacity expansion programme should have a higher priority as they pose specific risks, including connectivity between ports and railways. As the largest railway, KTZ generates around $US 2.5bn in annual revenue, but its debt burden means that it is unable to find commercial finance on competitive terms, relying on publicsector support through increases in direct government funding or loans from international financial institutions. ADY is in a similar position and relies for the most part on public-sector financing. It is Georgian government policy that GR should be financially independent and self-sustaining, but the report says a recent €500bn Eurobond issue “has topped its financial capacity for the foreseeable future” and that GR’s ability to fund its own capital needs is likely very limited. In November 2022, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan and Turkey signed a roadmap setting out the priority investment projects and other actions needed to improve the Middle Corridor Azerbaijan Railways (ADY) relies mainly on public-sector financing. Photo: ADY IRJ May 2024 between 2022 and 2027. In June 2023, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Kazakhstan agreed to create a joint logistics operator. Support and interest in providing investment and technical assistance has been confirmed by the World Bank itself as well as the European Union (EU), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB), together with other multilateral development banks and bilateral partners. In January, EIB Global, the arm of the European Investment Bank (EIB) dedicated to financing projects outside the EU, signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to co-finance sustainable transport projects with Kazakhstan and the Development Bank of Kazakhstan. In addition to other MoUs signed with Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, which are building a new railway to China, EIB Global is providing a total of €1.47bn and this is expected to attract further capital, resulting in total support of €3bn. According to an earlier EBRD study, total investment of €18.5bn is required if the Middle Corridor is to reach its full potential. Meanwhile, ADB is finalising its own study and says that it stands ready to support the development of the Middle Corridor in all forms. “Now is an opportune moment to make the Middle Corridor more competitive, expand its capacity, address inefficiencies, and reduce costs,” says Mr Charles Cormier, the World Bank’s regional infrastructure director for Europe and Central Asia. “A combination of shortterm gains in efficiency through various measures, along with medium-term investment, will strengthen the functioning of the Middle Corridor and catalyse its potential.” IRJ 31 Infrastructure | resilience Can satellite monitoring help to combat the risks of climate change? Taking the Lossan corridor in southern California as an example, Reijo Pold* of Value Space explains how satellite-based infrastructure monitoring can provide early warning of landslides and other disruptive events caused by climate change. M AINTAINING infrastructure to the required standard is the basis for ensuring the safety and continuity of rail services. Failure of a section of track or an infrastructure asset can result in potential fatalities, large repair costs, loss of service and reputational damage, leading to serious economic consequences. Climate change is already creating a surge in such events for the rail industry worldwide. Rising global temperatures create new environmental conditions, such as rising sea levels, prolonged periods of drought and higher than usual precipitation. These factors have a direct impact on rail infrastructure. Increased precipitation can create flooding and lead to ground saturation, which can weaken embankments and slopes, creating the risk of landslides that can move the track from its alignment or block it with debris. Periods of drought can cause drying, sinkage or cracking of underlying soils, leading to track misalignment or slope failures. A rise in sea level can increase the rate of coastal erosion, threatening railways built along the shoreline. Traditional methods of monitoring infrastructure conditions under such scenarios include using track condition data to detect changes to the alignment, which can then be addressed by remedial work or further on-site surveys to determine the underlying causes of infrastructure deterioration. But traditional methods might not easily identify some of the wider existing or developing spatial risks on or near the railway, such as signs of slope instability or ground movement. And given the major size of some networks, effective monitoring of climate change-related infrastructure risks can be a significant challenge. Operating almost in real time, satellite-based movement assessment and monitoring provides an in-depth way for infrastructure managers to understand where the risks are actually located. Analysis of data gathered by satellite radar enables highly accurate detection of movement that can point to existing or developing risks. These assessments can be delivered quickly and costeffectively, enabling the rail industry to identify, monitor and quantify the risks posed by climate change. 32 Both passenger and freight services on the Lossan corridor in southern California have been disrupted as a result of extreme weather events caused by climate change. Photo: X/GoOCTA Value Space has recently undertaken satellite-based analysis of ground conditions on sections of the 561.6km Lossan corridor in southern California, running from San Luis Obispo through Los Angeles to San Diego. It is the second-busiest inter-city passenger rail corridor in the United States, and also carries freight worth over $US 1bn every year. Both passenger and freight services on sections of the corridor have been disrupted as a result of the more extreme weather patterns caused by climate change, particularly those sections where the railway was built along the coast. They have experienced ground movement caused by coastal erosion that has affected track alignment, as well as unexpected landslides blocking traffic and damaging infrastructure. In September 2021 and in September 2022, two consecutive ground shifts took place on the shoreline at Cyprus Shore in San Clemente, between Los Angeles and San Diego, resulting in the track moving by as much as 381mm. After the September 2022 event, passenger services remained suspended for six months. Ground movement was attributed to coastal erosion which had worn away a counterbalance that allowed an ancient landslide to reactivate. The two events required emergency track stabilisation work costing a total of $US 21.7m. After the first shift, over 20,000 tonnes of large rocks and boulders were placed on the coastal side of the railway to counteract erosion and ground movement. More substantial works were carried out after the second ground movement event, with large metal anchors driven into the slope adjacent to the track to prevent the line from moving. Satellite-based analysis for the period between January 2021 and September 2022 revealed two notable movement clusters with different directions on the section at Cyprus Shore. The larger cluster moved up to 20mm per year, and the smaller one up to 14mm per year. Analysis of detailed movement data showed that this section of the coast and the slope were moving throughout the period of analysis. IRJ May 2024 In August 2021, just before the first ground shift, there was developing movement instability. Movement stabilised after the first ground shift and initial emergency stabilisation work, but movement continued up until the second ground shift in September 2022. The differently moving clusters on the shore and slope beneath the railway point to the accumulation of stress that is typical of a developing ground slide or movement event. Further satellite-based analysis between January 2021 and January 2024 revealed that movement is still present in the area, with buildings above a slope next to the railway experiencing movement of up to 19mm a year. Landslides at San Clemente Unusually high precipitation during the winters of 2022 and 2023 have caused an increase in landslide incidents in California. Railways have not been left untouched and several landslides have disrupted rail services in San Clemente, including a major event on April 27 2023 on the coastal slope below Casa Romantica cultural centre. Debris blocked the railway just below the slope and again after a second landslide in June that year. It cost $US 6m to clear the track and build a wall to protect the railway from further damage. Value Space’s analysis of the landslide area for the period from October 9 2021 to April 26 2023 identified ground movement on the slope of up to 46mm per year that was distinctly different from adjacent areas. Analysis revealed that the area of the landslide started showing warning signs in November 2022. The sides of the marked area in Figure 1 are moving in opposite directions and the mid-section of the marked area stands out for the lack of stable satellite-measured readings. These signs indicate possible strong stress on the slope that are typical of a developing landslide. These findings would have led to a warning being issued well ahead of the landslide, had the area been under satellite-based monitoring. The Lossan corridor has several longer sections along the coast that are already known or identified as being at risk from future weather and climate change-related incidents. The 2.72km section built on the Del Mar Bluffs north of San Diego has been of particular concern for a number of years, as the high sea cliffs here experience natural erosion resulting from earthquakes, rain, groundwater flows, breaking waves, and wind. The bluffs retreat naturally at an average rate of up to 152.4mm a year. IRJ May 2024 Eight surface slides on the bluffs have been reported in the area since summer 2018. Each time one takes place, rail traffic is stopped until inspection confirms that it is safe for operations to resume. Since 2003, the San Diego Association of Governments (Sandag) has completed several projects to stabilise the bluffs, with a new project due to begin this year at a cost of $US 78m. Value Space has analysed movements in the Del Mar Bluffs area for the period from January 24 2021 to January 15 2024 (Figure 2). Satellite-based assessment of the area identified 17 different movement clusters on the track section, among them were six areas of significant movement. Threats to service continuity on the Lossan corridor are not limited to the southern coastal sections at San Clemente and Del Mar Bluffs, however. Similar conditions exist on the northern part of the corridor. At a hearing of California Senate Transportation Subcommittee on Lossan Rail Corridor Resiliency last year, experts estimated the cost of stabilising these northern sections at $US 85m. For the period from January 2021 to January 2024, Value Space analysed the 85km section between Santa Barbara and Vanderberg and the 45km section between Santa Barbara and Ventura with different areas of detected movement marked. These examples demonstrate that satellite-based movement assessments can be conducted on longer sections of railway to identify, monitor and quantify climate change risks on a network level. With its highly accurate and up-todate deformation detection capabilities, satellite-based monitoring and risk assessment is set to help the rail industry as it has already benefitted the insurance sector in understanding the risks to critical infrastructure posed by climate change. As infrastructure managers face increasing disruption and losses caused by more extreme weather patterns, they should seek to implement new tools to stay ahead of the curve and proactively manage the risks associated with climate change. Expect satellite-based technology to become standard practice. IRJ * Reijo Pold is the Estonian-born, London-based founder of Value Space, a technology company that uses satellites to conduct assessments for commercial properties and infrastructure. Figure 1: Analysis showing discrepancies in movement at the site of the landslip on the Lossan corridor. Figure 2: Analysis of slope movements on the wider Del Mar Bluffs area. 33