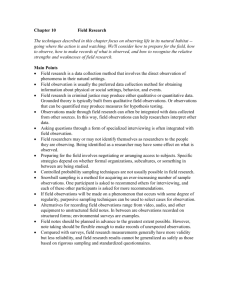

Social Research Methods Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches- Neuman (Pearson, 7th Edition)

advertisement