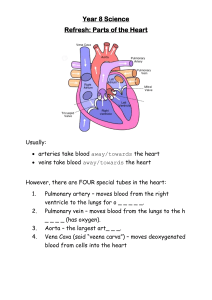

University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 UNIVERSITY OF SANTO TOMAS FACULTY OF MEDICINE AND SURGERY DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE PULMONARY and CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE 2 AY 2023-2024 SECTION OF PULMONARY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE TABLE OF CONTENTS General Description 2 Case Discussions 5 SGD 1: Asthma and COPD SGD 2: CAP and Pleural Effusion SGD 3: Lung Cancer and VTE Ward Work 9 Interview check list 10 Physical Examination of the Respiratory System 11 Lectures Basic Chest Imaging 13 ABG 16 Spirometry 17 Community Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) 20 COPD 27 Bronchiectasis 39 Tuberculosis 40 Sleep Disorders 47 Lung Cancer 49 Venous Thromboembolism 52 Emergency Acute Respiratory Failure / ARDS 58 Hemoptysis 59 Massive Pulmonary Embolism 61 WS 1 Clinico Radiologic Correlation 62 WS 2 ABG / Clinico Radiologic Correlation 65 WS 3 Spirometry / Inhaler Gadget / Peakflow 74 WS 4 Ultrasound 80 Workshops Team-Based Learning for Third Year Medical Students TBL 1 Asthma 82 TBL 2 Dyspnea (Cardio-Pulmo Integration) 83 Additional Notes: 1 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 Bronchial Asthma 84 Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) / Pulmonary Hypertension (PH) 96 UNIVERSITY OF SANTO TOMAS FACULTY OF MEDICINE AND SURGERY DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE PULMONARY and CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE AY 2023-2024 GENERAL DESCRIPTION • Pulmonary Medicine: Tuesday and Thursday • 7:00 am to 12:00 nn CHAIRMAN, Department of Medicine: Melvin Marcial, MD, MHPEd CHIEF OF SECTION of Pulmonary Medicine: Julie Christie G. Visperas, MD, MHPEd PULMONARY MEDICINE LEADER: Julie Christie G. Visperas, MD, MHPEd PULMONARY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE ENTRY COMPETENCIES: • Basic Anatomy and Physiology of the Respiratory System PULMONARY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE ENTRY COMPETENCIES: • Basic Anatomy and Physiology of the Respiratory System TERMINAL COMPETENCIES: At the end of the module, the third year students should be able to: • review the pathophysiologic aspects of the Respiratory system as found in disease states • correlate the patient manifestations with the pathophysiology involved in Respiratory diseases • arrive at a logical diagnosis based on signs and symptoms • formulate a logical, rational, and cost effective medical plan for patients, to include both diagnostic and therapeutic aspects • apply ethical principles in the approach to the diagnosis and management of patients with Respiratory diseases LEARNING ACTIVITIES: LECTURES • teacher / specialist oriented activity • most common diseases of the Respiratory system will be presented to the students, with focus on clinical application of basic concepts, as well as updates on diagnosis and treatment • an interactive/ student oriented approach will be utilized as much as possible to enhance learning CLINICAL CASE CONFERENCE This is the venue for presenting cases admitted in the UST Hospital, which will illustrate any or all of the following: - interesting / rare cases in Respiratory Medicine, as this may be the only opportunity for the students to be exposed to such problems - cases with complicated/ multidisciplinary courses- so that the students may be made aware of the complex interactions among the various organ systems and specialties - classical textbook cases so that the students may appreciate further the clinical applications of what they may have been given as didactics 2 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine - Revised August 2023 diagnostic dilemmas, so that the students may observe how the various consultants dissect the patient’s problems in order to come up with a logical diagnosis. Ethical issues which may be encountered. Question and answer formats and Interactive key pads/polls will be used to encourage the medical students to participate in the discussion. CASE DISCUSSIONS 1. student lead and facilitator guided 2. cases are prepared before-hand 3. students will: 3.1. formulate learning objectives relevant to the case 3.2. present a concept map ( this will be their guide for the management of the patient) 3.3. submit simple and processed problem list WARD WORK - self directed and tutor-guided activity - provides an opportunity for the students to handle actual patients in the ward - to get a complete medical history and physical examination, identify the pertinent problems of the patient, arrive at a logical diagnosis, and plan a management scheme - the students may also be asked to accompany their patients to certain procedures as this will enhance their learning experience - one written history with case discussion will be submitted per module WORKSHOP - student - oriented, facilitator guided - provides an opportunity for the students to have hands-on training in/ with skills/procedures/algorithms used in the respiratory system the various EXAMINATIONS - short quizzes will be given per week, based on the reading assignments as well as the previous workshops/ Clinical Case Discussion - module examinations will be given at the end of each shift STUDENT EVALUATION MODULE/Shifting Grade = 98% (70% from the Class Standing + 30% from the Shifting Examination) 2% (Attendance Grade) Class Standing = 70% 25% from Cluster Exams/Quizzes (12.5% Cardio; 12.5% Pulmo) 45% Module Specific Gradable Activities Cardio-Pulmo Module Gradable Activity: Interactive Case Discussion/SGD (5 Cardio + 3 Pulmo)= 15% Cardio; 15% Pulmo History (Patient Write Up: 1 Cardio and 1 Pulmo) = 15% CARDIO; 15% PULMO Ward/ Simulated Patient Encounter = 10% TBL in Pulmo iRAT = 5% tRAT/tAPP = 10% Attitude = 10% Peer Evaluation = 5% REFERENCES: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 21st Edition Pleural Diseases 6th edition by Richard Light Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic 3 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (updated 2022) IDSA and ATS Guidelines on Community Acquired Pneumonia 2019 Philippine Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Diagnosis, Empiric. Management, and Prevention of Community-acquired (CPG 2016) Manual of Procedures for the National TB Control Program (Philippines, 6th Edition, 2020), Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control of Tuberculosis in Adult Filipinos: 2016 Update, International Standards for Tuberculosis Care 3nd Edition (ISTC 3rd ed., 2014 WHO’s Guidelines for the Treatment of Drug-susceptible Tuberculosis and Patient Care Global Initiative for Asthma updated 2023 Philippine COVID-19 Living Recommendations, Institute of Clinical Epidemiology, National Institutes of Health, UP Manila; PSMID; DOH. January 3, 2022 SGD1: Breathless in bed Gene Ehica, a 52 year old, married Filipino male, casino dealer consulted because of dyspnea. Three weeks before consultation, the patient experienced awakenings around 3 am where he would have dyspnea that would resolve spontaneously initially and later with the use of a blue inhaler that was prescribed a years ago for and emergency room visit.. This would be associated with a high-pitched sound as he exhaled. He used to walk to work as he lived just one kilometer. away but now takes a tricycle. He would experience some cough and shortness of breath while dealing cards so he would use 2 puffs of the inhaler before working, which he did five days weekly. 4 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 Review of systems revealed he had daily morning nasal stuffiness. Family history: Father - COPD and CAD, died at the age of 76. Mother and brother have asthma Past medical history - recall being told to have childhood asthma but has been relatively symptom-free except for some easy fatiguability starting three years ago. Treated for TB for 6 months 5 years ago under DOTS. Hypertensive on maintenance medications Personal history: Non-smoker, non-alcoholic Occupational history: card dealer at the casino for 25 years Physical examination: Conscious, coherent, cooperative BP: 120/80 RR: 20 cpm CR: 100 bpm T: 37 C Skin is warm and moist No alar flaring, no circumoral cyanosis, no sternocleidomastoid muscle retractions. Symmetrical chest expansion, no retractions, equal tactile fremitus, resonant, no adventitious lung sounds. On forced expiration, a wheeze could be appreciated. Other examinations were normal. 1. Make a summary statement/ illness script of the case above. 2. What is your most likely diagnosis? What information in the history and physical examination findings are contributory? 3. What are your differential diagnoses? 4. What are the contributing factors to dyspnea? 5. Which is a diagnostic examination of choice? How is it expected to help in the diagnosis? 6. Interpret the spirometry results which will be shown to you by your facilitator. Is it compatible with the patient presented? 7. What other tests may be helpful in disease management? 8. What is the pharmacological management approach? 9. What non-pharmacological approaches can we employ? 10. How do we know the disease is under control? 11. Construct a follow-up program for the patient. 12. What are the indicators that a patient should seek medical attention? 13. When should the patient be referred to a specialist? 14. Construct a concept map. SGD 2 YOU TAKE MY BREATH AWAY CASE DISCUSSION 2 / SGD 2 YOU TAKE MY BREATH AWAY OBJECTIVES: • Recognize the most common signs and symptoms of patients with Pneumonia and Pleural effusion • Correlate the manifestations with the pathophysiology of the disease/s • Recommend procedures that will aid in the diagnosis and management of Pneumonia and Pleural effusion • Classify Pneumonia patients according to current guidelines • Know the most common organisms involved in each classification • Prescribe management for Pneumonia and Pleural effusion • Recognize complications associated with management of pleural effusion; recommend interventions for these complications\ 5 • University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 Make simple and processed problem lists CASE: Vina Vahasia, a 50 year old teacher, consulted for dyspnea. Eight days prior to admission, the patient started having cough with yellowish phlegm, as well as fever with a temperature range of 37.5- 38.6C. Three days ago, she also started experiencing sharp left upper quadrant pain which intensified whenever she would cough. She also mentions that around this time, she also started having exertional dyspnea when going up to the second floor of her apartment. She had a chest x-ray done, was told she had pneumonia, and was prescribed antibiotics, However, she discontinued the antibiotics after taking only 1 dose because of nausea and vomiting. Two days ago, she started dyspnea even on activities of daily living. She also felt short of breath when lying down on her right side, and was only comfortable when she used 3 pillows at night. The persistence of the cough and worsening of the dyspnea prompted consultation. (-) weight loss; (-) anorexia; (-) chest heaviness; (-) PND; (+) nocturia. She is a known Diabetic since 2004, with irregular intake of Glibenclamide. Her CBG results range from 160-180 mg/dl. She does not smoke nor drink alcoholic beverages. Family history is (+) for DM. GS: conscious, alert, aware, speaks in short sentences, but prefers a semi-upright position; prominence of the SCM. VS: BP 110/70, CR 100/min, RR 24/min, T 37.9C; O2 sats 93% at RA Funduscopic exam: (+) exudates OU Chest: Lagging of the left hemithorax, decreased fremiti, dullness, and decreased breath sounds from T6 downwards Cardio: apex beat was at the 5 th LICS, parasternal area; heart sounds normal; JVP and CAP normal; peripheral pulses ++ Abdomen: unremarkable Ext: no edema NE: 20% sensory deficit both feet GUIDE QUESTIONS: 1. Make a summary statement/ illness script of the case above. 2. Correlate the manifestations of the patient with the possible pathophysiology of the disease/s a. Eight days fever, cough, dyspnea, pleuritic pain b. Shortness of breath when lying on her right side c. Progressive shortness of breath d. Nocturia, CBG results, retinopathy, neuropathy e. Speaks in short sentences, prefers semi upright position, SCM prominence, RR 24; O2 sats 93% f. Lagging of L, decreased fremiti, dullness and decreased BS T6 downwards, apex beat displaced to the contralateral side 6 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 g. Nausea and vomiting 3. What is our admitting impression? Make a simple and processed problem list. 4. How do we classify our patient (what guidelines do we use)? What is the classification of our patient? 5. What is the importance of classifying the patient? 6. What are the most common organisms involved in CAP? What are the recommended antibiotic coverage? 7. What labs/ procedures will we request for? Why? What are the expected results? 8. Interpret the chest imaging and ultrasound which will be shown to you by your facilitator on the day of the SGD. 9. Does our patient have a transudate or an exudate? Is it possible to differentiate them based on clinical manifestations? 10 Ultrasound guided Thoracentesis was done. 800 cc of slightly turbid amber colored fluid was obtained . Interpret the test results for the pleural fluid which will be shown to you on the day of the SGD. 11. When do we expect response to treatment? What if the patient is not improving? 12. Is there any way to prevent Pneumonia? SGD 3 Intended Learning Outcomes: 1. Recognize the common risk factors and manifestations of lung cancer. 2. Discuss the approach to the evaluation of a pulmonary mass. 3. Discuss the approach to the management of lung cancer. 4. Discuss the risk factors for VTE. 5. Discuss the approach to the diagnosis and management of VTE. Case Scenario Part 1: A 51-year-old female consulted because of an incidental finding of a pulmonary mass noted on her routine annual physical examination chest x-ray. She is currently 7 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 asymptomatic. She denies cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, chest pain, unexplained weight loss and fever. Other than the usual seasonal flu and common childhood illnesses, she had no history of previous illness. She is not hypertensive nor diabetic. She had no history of previous PTB diagnosis nor treatment. Her obstetric history is G1P1 (1001), with no history of oral contraceptive use. Her family medical history is likewise unremarkable. She does not smoke. She is a businesswoman residing in a high-rise condominium in BGC. Her physical examination was likewise unremarkable. Her vital signs were as follows: BP 120/80 CR: 72 RR: 18 Temp. 36.7 O2 sat: 98% on room air. Her neck was supple with no palpable cervical lymph nodes. There was symmetrical chest expansion, no retraction, equal tactile and vocal fremitus, resonant on percussion of both lungs, lung sounds were normal. There was no edema. Other physical examination findings were normal. A chest CT scan with contrast was done and representative cuts are shown below. Chest X-ray: Chest CT scan with contrast: GUIDE QUESTIONS: 1. Make a summary statement/ illness script of the case above. 2. What other data in the history and PE should you look for? Describe the chest xray. 3. Which of her clinical features are compatible with a benign disease, and which ones are compatible with a malignant process? 4. Give your presumptive diagnosis, presumptive cell type and presumptive staging based on the given clinical data. 5. How would you establish the diagnosis and clinical stage? 8 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 6. Discuss the approach to pre-treatment planning? Continuation… After your clinical evaluation and pre-treatment planning, you diagnose her to have Adenocarcinoma of the Lungs, Stage 3a (T3N0M0). Her performance status is generally good (ECOG 0). 7. What are the goals of treatment for this case? What treatment options will you recommend for her? 8. What are the goals for follow-up care? Part 2: After a course of neo adjuvant therapy, she underwent VATS with left lower lobectomy. She tolerated the procedure well, there was no immediate post-operative complication noted. She was apparently recovering well from surgery until, on her 5th post-op day when she suddenly complained of dyspnea with right-sided pleuritic pain. Her vital signs were as follows: BP = 120/80, CR 120, RR 28, Temp 36.8, O2 Sat 92% while on 5lpm O2 supplementation via nasal canula. You are considering the possibility of pulmonary embolism. GUIDE QUESTIONS: 1. What are her risk factors for pulmonary embolism? 2. What is the clinical probability of pulmonary embolism in this case? What other symptoms and signs should you look for to strengthen your diagnosis? 3. How will you manage the patient? WARD WORK / Virtual Patient Encounter/Telemedicine: INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: WEEK 1 - History and PE - review of IPPA 1. Discuss clinical manifestations of patients manifesting with respiratory distress and with respiratory failure 2. Correlate the various manifestations with pathophysiology involved 3. Review the physical examination techniques (IPPA) in patients with pulmonary diseases WEEK 2 - Case 1. Identify patients with Pulmonary disorders 2. Obtain significant data—subjective and objective—from patients 3. Correlate the data obtained and formulate a logical diagnosis 4. Discuss differentials, diagnostic and therapeutic plans WEEK 3 - clinical correlation, discussion of case 1. Critique the patient history / PE obtained the previous week 2. Discuss x-rays / ABGs / Mechanical ventilator management bedside 9 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 INTERVIEW CHECK LIST ITEM A. OPENING 1. Initial greeting a. verbal introduction b. shakes hands of patient c. addresses patient appropriately— Mr., Mrs, Tatay, Nanay, Lola 2. puts patient at ease B. INFORMATION GATHERING 3. questioning: uses open-to-closed ended questions 4. expounds on problem(s) 5. establishes a narrative thread 6. problem survey 7. clarification C. CLOSING 8. encourages patient’s questions DEFINITION SCORE States name and role on team Greets patient and companions warmly Minimizes distractions; attends to patient’s comfort and privacy MAXIMUM SCORE: 10 Focuses by starting with open questions and ending with closed questions. Avoids multiple and leading questions Asks and verifies problem(s) appropriately Maintains a chronological account. Lets the patient tell the story without interrupting and listens attentively. Follows significant leads Asks “what else?” until all major concerns are expressed. Goes over review of systems Restates the content (paraphrases patient’s answers) and checks for accuracy, i.e. “Let me see if I have this right?” MAXIMUM SCORE: 50 Does not avoid questions and answers clearly 9. states appreciation for patient’s efforts MAXIMUM SCORE: 10 D. FACILITATION SKILLS 10. eye contact 11. invites/ reinforces patient’s responses with nods, and repeating patient’s last statement Conveys interest and attentiveness MAXIMUM SCORE: 10 E. FLOW 12. overall feeling is that the interview moves smoothly from one component to another with key points summarized and ending with a smooth closure MAXIMUM SCORE: 20 TOTAL SCORE: 10 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM RULE OUT THE PRESENCE OF RESPIRATORY DISTESS/ IMPENDING RESPIRATORY FAILURE 1. 2. Mentions if the following are present: (at least 4) 4 points Abdominal paradox Central cyanosis Altered sensorium Preference for the upright position/ tripod position Prominence of the SCM Retractions Speaks in phrases (ask the patient a question and note how he responds States if there is respiratory distress/ failure, or if we can now proceed with the rest of the physical examination 1 point 5 points DONE NOT DONE ONCE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS / FAILURE HAS BEEN RULED OUT, PROCEED WITH THE STRUCTURED PE OF THE CHEST NOT DONE 1. DONE INCOR RECTLY DONE PREPARATION Washes hands Greets patient, introduces self Explains procedure, asks for permission/ consent Asks patient to remove shirt/ blouse- provides drapes if necessary 4 points 2. INSPECTION 3. Describes the appearance of the chest- symmetry/ masses/ bulges/ scars/ lesions- both anterior and posterior Compares antero-posterior to lateral diameter States which is wider- antero-posterior or lateral diameter 3 points INSPECTION/ PALPATION 3.1. 3.2. 3.3. TRACHEA While facing the patient, inspects the position of the trachea Inserts index fingers on the spaces on either side of the trachea Observes whether the spaces on either side are equal States if trachea is midline 4 points CHEST EXPANSION While facing the patient, places thumbs along costal margins and xiphoid processes with palms resting on the anterior chest Asks patient to take a deep breath Observes for movement of his/ her hands Describes if chest wall movement is symmetrical/ asymmetrical Moves toward back of patient Locates inferior angle of the scapula Palpates for the 10th ICS along the midscapular line Puts both palms flush against the chest wall along the 10th ICS, grasping the posterior chest Moves both hands medically (towards the vertebral line) so as to form a crease along the mid-back Asks the patient to take a deep breath Observes for movement of his/her hands with the chest wall movement Describes if the chest wall movement is symmetrical/ asymmetrical 12 points PALPATION FOR TACTILE FREMITI Palpates gently across anterior and posterior chest Describes if there are any points of tenderness/ bulges/ masses Asks patient to cross his arms across his chest Moves toward back of patient 11 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine 4. 4.1. 4.2. 5. 5.1. 5.2. 6. Revised August 2023 Rests the ulnar surface of his/her hand in the upper posterior chest, medial to the scapula Asks patient to say “ninety-nine” or “tres-tres” Feels for vibration in the area (tactile fremiti) Moves hand to other side and does same procedure Moves hand to a lower position in the chest, and does same procedure Always compares one side to the other while moving from upper to mid chest area, initially always medial to the scapula Once below the level of T7/ 7th ICS, examines for tactile fremiti along the scapular lines and posterior axillary lines, always comparing one side to the other States if the tactile fremiti are equal 12 points PERCUSSION PERCUSSION OF LUNGS Reminds patient to keep his arms crossed Beginning at the upper lung field, aligns finger (of pleximeter hand) along intercostal space along the paravertebral line, making sure that it is only the distal 3rd of the finger resting on the chest wall Strikes the distal 3rd of the finger with the tips of the fingers of the free hand (plexor) Listens for percussion sound produced Does same procedure, moving from one side of the chest to the other, from the upper to the lower lung fields 5 points DIAPHRAGMATIC EXCURSION Asks the patient to take a deep breath and hold it Percusses along the scapular line and locate the area of dullness which is the level of the diaphragm Marks that level Asks patient to do normal breathing Instructs patient to exhale as much as possible Percuss upward from marked point and locate the area of dullness States positions of both levels Moves to opposite side and repeats procedure 8 points AUSCULTATION BREATH SOUNDS Makes sure that patient still has his arms crossed over his chest Asks patient to take slow deep breaths through his mouth Auscultates with the diaphragm of the stethoscope in the same areas used in palpation and percussion (moving from upper lung field to lower, always comparing one side to the other) Listens to 2-3 respiratory cycles before moving to next position States if there are adventitious breath sounds 5 points VOCAL FREMITI Repeats the same procedure but asks patient to say “tres-tres” or “ninetynine” instead of taking deep breaths Listens for vocal fremiti States if vocal fremiti are equal 3 points ENDING THE PHYSICAL EXAMINATION Informs patient that examination is done Asks patient if he needs help dressing Thanks patient 3 points TOTAL POINTS PERFECT SCORE 64 points 12 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 LECTURES : LECTURE 1 : BASIC CHEST IMAGING INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Review normal chest radiograph 2. Assess the quality of the chest radiograph 3. Identify and interpret radiograph abnormalities 4. Correlate radiographic result of clinical manifestations 5. Identify normal chest ultrasonography findings 6. Interpret abnormal chest ultrasonography findings 1. QUALITY OF FILM 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. PA view Position Penetration full Picture full insPiration 2. BASIC CHEST X-RAY INTERPRETATION Are There Many Lung Lesions? A 1. 2. 3. 4. costophrenic sulci contour of hemidiaphragm level of hemidiaphragm Right usually higher than left T 1. symmetry of thoracic cage / ICS 2. rib fractures M 1. trachea 2. heart 3. hila (L usually higher than left) LL 1. compare one lung to the other lung NORMAL CHEST ULTRASOUND - bat sign lung sliding comet tails sea shore sign LUNG PATHOLOGIES PLEURAL EFFUSION – sonolucency- usually above the diaphragm – loculated effusion PNEUMOTHORAX – absence of lung sliding, identification of lung point; bar code sign 13 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 PNEUMONIA – dynamic air bronchograms Emphysema A – flat/depressed hemidiaphragm; low set T – widened interspaces M – dropped heart – investigate for Pulmonary hypertension (look at Pulmonary arteries) LL – hyperluscent lungs, +/- bullae, pruning of blood vessels Pneumothorax A – +/- flattening of one hemidiaphragm on the side of the pathology; +/blunting of costophrenic sulcus (secondary to bleeding) T – +/- widened interspaces on affected side M – +/- shifting of midline structures contralaterally LL – presence of visible visceral pleural line- radiographic hallmark Consolidation A – may be normal T – normal M – +/- silhouette sign depending on the lobe involvement LL – presence of air bronchograms Obstructive Atelectasis A – hemidiaphragm may be affected depending on the size of atelectasis T – +/- narrowed interspaces on affected side with compensatory widening on opposite side M – +/- shifting of midline structures ipsilaterally LL – homogenous opacification of affected area Cicatricial Atelectasis A – hemidiaphragm may be affected depending on the size of atelectasis T – +/- narrowed interspaces on affected side with compensatory widening on opposite side M – +/- shifting of midline structures ipsilaterally LL – inhomogenous opacification of affected area, with air bronchograms Effusion A – blunting of costophrenic sulcus, or non visualization of hemidiaphragm, due to presence of fluid T – +/- widened interspaces on affected side (may be hard to visualize because of the presence of fluid) M – +/- shifting of midline structures contralaterally depending on amount of fluid as well as presence of any other underlying lung pathology LL – homogenous opacification with a lateral upward curve (meniscus sign) -on lateral decubitus view – the homogenous density (fluid) occupies the most dependent portion of the chest wall (layering) if it is FREE within the pleural space Cavitary Tuberculosis A – costophrenic sulci not affected unless there is concomitant effusion or thickening T – interspaces not affected unless there is also volume loss/ atelectasis M – +/- shifting of midline structures depending on volume loss LL – lucency within the lung parenchyma usually with an irregular margin. 14 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 Bronchiectasis A – costophrenic sulci not affected unless there is concomitant effusion or thickening T – interspaces not affected unless there is also volume loss/ atelectasis M – +/- shifting of midline structures depending on volume loss LL – honeycomb densities Metastatic lesions A – costophrenic sulci not affected unless there is concomitant effusion or thickening T – interspaces not affected unless there is also volume loss/ atelectasis M – +/- shifting of midline structures depending on volume loss LL – cannon ball appearance; brocnhoalveolar spread; multiple nodules REFERENCES: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 20thEdition Chest Radiography (Felson) Module on Pulmonary Medicine Workbook NOTES: 15 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 LECTURE 2 : ARTERIAL BLOOD GAS (ABG) INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Learn the usefulness of the arterial blood gas 2. Know the normal values 3. Interpret arterial blood gases 4. Present a simple algorithm in the interpretation of ABG results 5. Apply various equations to blood gas interpretation and clinical management NOTES: 16 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 LECTURE 3 : SPIROMETRY INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Define ventilation 2. Enumerate the organs involved in ventilation 3. Describe the physiologic changes during ventilation 4. Define the different ventilatory defect (obstructive, restrictive and mixed) 5. Show how a spirometry testing is done 6. Enumerate the parameters measured and define its normality 7. Show and rationalize an algorithm of how a spirometry report in interpreted 8. Interpret several spirometry report and correlate with the possible diagnosis of clinical cases 9. Enumerate and show examples of how spirometry is used in clinical practice REFERENCES: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 21st Edition American Thoracic Society Statement on Pulmonary Function Testing Module on Pulmonary Medicine Workbook NOTES: 17 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Concept of Ventilatory Defect Site of Pathology Ventilatory Defect Airways Obstructive P: Pleura A: Alveoli (lungs) I: Interstitium (lungs) N: Neuromuscular apparatus T: Thoracic cage Restrictive Primary Loop Manifestation Low air flow Short exaggerated concavity Low lung Narrow volume Revised August 2023 FEV1/FVC FVC Almost always low Always low 1. Breathing Maneuver/ Parameters Measured/ Interpretation Algorithm 1.1. Forced Vital Maneuver: After several tidal breathing, subject inhale to TLC then forcefully, rapidly, completely expire to RV for at least 6 seconds and then forcefully and rapidly inspire back to TLC 1.2. Parameters Measured 1.2.1. Forced Expiratory Volume in one Second (FEV1): From TLC, it is the volume forcefully expired by patient for one second. It is considered as an airflow parameter 1.2.2. Forced Vital Capacity (FVC): The volume forcefully expired from TLC to RV. Considered as an airflow parameter 1.2.3. FEV1/FVC: Considered as an airflow parameter 1.3. Parameters for Normality 1.3.1. GOLD Standard: Lower Limit of Normality is the 5 th percentile 1.3.2. Alternative Standard 1.3.2.1. FEV1/FVC: anything below 0.7 or 70 is considered abnormally low 1.3.2.2. FEV1 or FVC: anything below 80% of the predicted is considered abnormally low 1.4. Significant response to Bronchodilator: Labelling requires 2 conditions: FEV1 or FVC increase of at least 12% from baseline: FEV1 or FVC increase of at least 200 ml from baseline 2. Sequence of Interpretation 2.1. Is it a good quality test? 2.2. Is there an obstructive ventilatory defect? 2.3. Is there a probable restrictive ventilatory defect? 2.4. If a ventilatory defect is present, what is the severity? 2.5. Is there a significant response to bronchodilator? 18 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 FLOW CHART FOR THE INTERPRETATION OF A SPIROMETRY RESULT FLOW CHART FOR THE INTERPRETATION OF A SPIROMETRY RESULT 19 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 LECTURE 4 : COMMUNITY ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA (CAP) INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Recognize the most common signs and symptoms of patients with Community Acquired Pneumonia 2. Correlate the manifestations with the pathophysiology of the disease 3. Recommend procedures that will aid in the diagnosis and management 4. Classify patients according to current guidelines 5. Know the most common organisms involved in each classification 6. Prescribe initial management based on the classification of the patient 7. Provide differentials for patients who do not respond to medications REFERENCES: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 21st Edition IDSA and ATS Guidelines on Community Acquired Pneumonia 2019 Philippine Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Diagnosis, Empiric. Management, and Prevention of Community-acquired (CPG 2016) Module on Pulmonary Medicine Workbook NOTES: 20 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 Clinical Practice Guidelines for Community Acquired Pneumonia Reference Card: Pneumonia Severity Index Calculation of the patient’s PSI allows classification of the severity of pneumonia using the scaled rankings in the following table: Table: severity of Pneumonia Scale Class Class I Class II Class III Class IV Class V Description of severity Exhibit no severe clinical signs and aged less than 50 yrs. old. This class ha a 30-day mortality rate of 0.1%, however, it is not relevant to residents of RACFs. PSI score 1-70. This class has a 30-day mortality rate of 0.6% and are usually treated in the RACF home. PSI score 71-90. This class has a 30-day mortality rate of 0.9% and should be assessed for appropriateness of IV treatments in the facility of hospital. PSI score 91-130. This class has a 30-day mortality rate of 9.3% and I usually treated in hospital. PSI score >130. This class has a 30-day mortality rate of 29.2% and should be treated in hospital PSI risk class I – Patient age ≤50 years and patient has none of the following: History of: Clinical signs: • Neoplastic disease • Acutely altered mental state • Liver disease • Respiratory rate ≥30 per minute • Congestive cardiac failure • Systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg • Cerebrovascular disease • Temperature <35oC or ≥40oC • Renal disease • Pulse rate ≥125 per minute PSI risk classes II, III, IV and V – calculate score using the following information: Factor PSI score Resident’s score Patient age Age in years (male) or age in years (female) -10 Nursing home (but not hostel) resident +10 Coexisting illness - Neoplastic disease - Liver disease - Congestive cardiac failure - Cerebrovascular disease - Chronic renal disease Signs on examination +30 +20 +10 +10 +10 - Acutely altered mental state - Respiratory rate ≥30 per minute - Systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg - Temperature <35oC or ≥40oC - Pulse rate ≥125 per minute Results of investigation +20 +20 +20 +15 +10 21 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 PNEUMONIA SEVERITY INDEX Identifying the level of risk in CAP patients: The risk factors and how they are scored: Patient Characteristic Males Females Nursing home residents Comorbid Illness Neoplastic disease Liver disease Congestive heart failure Cerebrovascular disease Renal disease Physical Examination Findings Altered mental status Respiratory rate 30 breaths per minute or more Systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg Temperature < 35oC or 40oC or more Pulse 125 beats per minute or more Laboratory Findings pH< 7.35 BUN > 10.7 mmol/L Sodium less than 130 /L Glucose > 30 percent Hematocrit < 30 percent Partial pressure of arterial oxygen < 60 mm Hg Pleural effusion Demographic Factors (Age) Points Assigned* Age (in years) Age (in years) -10 +10 +30 +20 +10 +10 +10 +20 +20 +20 +15 +10 +30 +20 +20 +10 +10 +10 +10 *A risk score (total point score) for a given patient is obtained by summing the patient age in years (ago minus 10 for females) and the points for each applicable patient characteristics. *Oxygen saturation < 90 percent was considered abnormal in the Pneumonia PORT cohort study. The application of the PSI to the initial site of treatment decision (translation research) combines the PSI risk score and in addition considers the status of arterial oxygenation when used to guide the initial site of treatment. How Risk Levels Are Scored Risk Level 30-Day Mortality Risk Class Based on: Low Less 0.5 percent I Algorithm Low Greater than or equal to 0.5 and less than 1.0 percent II 70 or fewer points Low Greater than or equal to 1.0 and less than 4.0 percent III 71-90 points Moderate Greater than or equal to 4.0 and less than 10.0 percent IV 91-130 points High Greater than or equal to 10.0 percent V Greater than 130 points Source: Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia.NEngl J Med 1997;336(4):242-50. 22 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 CURB-65 AND CRB-65 SEVERITY SCORES FOR COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA Clinical factor Points Confusion 1 Blood urea nitrogen > 19 mg per dL 1 Respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths per minute 1 Systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg or Diastolic blood pressure ≤ 60 mm Hg Age ≥ 65 years 1 1 Total points: 0 Deaths/total (%)* 7/1,223 (0.6) 1 31/1,142 (2.7) 2 69/1,019 (6.8) Short inpatient hospitalization or closely supervised outpatient treatment 3 79/563 (14.0) Severe pneumonia; hospitalize and consider admitting to intensive care 4 or 5 44/158 (27.8) CURB-65 score Recommendation† Low risk; consider home treatment 0 Deaths/total (%)* 2/212 (0.9) Very low risk of death; usually does not require hospitalization 1 18/344 (5.2) Increased risk of death; consider hospitalization 2 30/251 (12.0) 3 or 4 39/125 (31.2) CRB-65 score‡ Recommendation† High risk of death; urgent hospitalization CURB-65 = Confusion, Urea nitrogen, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, 65 years of age and older. CRB-65 = Confusion, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, 65 years of age and older. * - Data are weighted averages from validation studies.1-2 † -Recommendation are consistent with British Thoracic Society guidelines.3 Clinical judgment may overrule the guideline recommendation. ‡ - A CRB-65 score can be calculated by omitting the blood urea nitrogen value, which gives it a point range 0 to 4. This score is useful when tests blood tests are not readily available. 1. 2. 3. Aujesky D, Auble TE, Yealy DM, Stone RA, Obrosky DS, Meehan TP, et al. Prospective comparison of three validated prediction rules for prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2005; 118-384-392. Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, Boersma WG, Karalus N, Town Gl, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58:377-382. British Thoracic Society Pneumonia Guidelines Committee. BTS guidelines for the management of communityacquired pneumonia in adults – 2004 update. Available at http://www.britthoracic.org.uk/c2/uploads/MACAPrevised apr04.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2006. 23 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 FOR LOW RISK PATIENTS - ADMIT WHEN: - complications of pneumonia - exacerbation of underlying disease - inability to take oral medications or receive out patient care - multiple risk factors - PLUS o hypoxemia O2 sat < 90% or PaO2 < 60mmHg o shock o decompensated co-existing disease o pleural effusion o inability to take oral medications o social problems o lack of response to previous antibiotic treatment WHERE SHOULD WE ADMIT PATIENTS? ADMIT TO ICU IF: - septic shock requiring vasopressors - ARF requiring intubation or MCV - 3 of the ff minor criteria: o RR > 30/min o P/F < 250 o Multilobar infiltrates o Confusion/ disorientation o Uremia (BUN > 19 mg/dl) o Leucopenia (< 4000 cells / mm3) o Thrombocytopenia (< 100,000 cells / mm3) o Hypothermia (< 36C) o Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation MOST PROBABLE ORGANISMS - OUTPATIENT - S pneumonia, M pneumonia, H influenza, C pneumonia, respiratory viruses - IN PATIENT NON ICU - S pneumonia, M pneumonia, H influenza, C pneumonia, Legionella spp, anaerobes (aspiration), respiratory viruses - IN PATIENT ICU - S pneumonia, S aureus. Legionella, Gram (-) bacilli, H influenza EMPIRIC THERAPY OUTPATIENT - previously healthy, no use of antibiotics in previous 3 monthso Macrolide, Doxycycline - with co-morbidities o respiratory FQ, B lactam + macrolide - high probability of macrolide resistant Strep even in patients with no co-morbiditieso respiratory FQ, B lactam + macrolide INPATIENT NON ICU - respiratory FQ, B lactam + macrolide INPATIENT ICU - B lactam + either azithromycin or a respiratory FQ INPATIENT ICU with Psedomonas infection - antipseudomonas B lactam + cipro or levofloxacin or B-lactam + aminoglycoside + azithromycin or B-lactam + aminoglycoside + antipneumococcal fluoroquinolone (penicillin allergy - substitute aztreonam for the B-lactam) INPATIENT ICU with community acquired MRSP - add vancomycin or linezolid 24 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 25 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 26 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 LECTURE 5 : CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE (COPD) INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Classify the different severities and stages of COPD 2. Develop an appropriate pharmacological and non-pharmacological regimen for patients with COPD based on disease severity, as well as for exacerbations of COPD 3. Create a proper prescription, treatment monitoring plan, and the treatment regimen for a COPD patient 27 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 28 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 29 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 30 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 31 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 32 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 33 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 34 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 35 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 36 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Revised August 2023 37 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine 38 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine LECTURE 6 : BRONCHIECTASIS INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Define bronchiectasis 2. Recognize common signs and symptoms of bronchiectasis 3. Identify common causes of bronchiectasis 4. Apply treatment principles in a given case REFERENCES: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 21st Edition NOTES: 39 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine LECTURE 7 : TUBERCULOSIS INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Familiarize students on the clinical signs and symptoms, risk factors and laboratory evidence associated with active TB disease. 2. Review current local (DOH-NTP Manual of Procedures) and international (ISTC 2014 and WHO Guidelines) recommendations for TB diagnosis and management for drugsusceptible and drug-resistant TB, even in cases of TB/HIV co-infection – including disease classification, registration group, treatment regimens and outcomes. Int’l Std for TB Care: • To ensure early diagnosis, providers must be aware of individual and group risk factors for tuberculosis and perform prompt clinical evaluations and appropriate diagnostic testing for persons with symptoms and findings consistent with tuberculosis. • All patients, including children, with unexplained cough lasting two or more weeks or with unexplained findings suggestive of tuberculosis on chest radiographs should be evaluated for tuberculosis WHO 2018:Standards for early TB detection • For persons with signs or symptoms consistent with TB, performing prompt clinical evaluation is essential to ensure early and rapid diagnosis. • All persons who have been in close contact with patients who have pulmonary TB should be evaluated. The highest priority contacts for evaluation are those: o with signs or symptoms suggestive of TB; o aged <5 years; o with known or suspected immunocompromising conditions, particularly HIV infection; o who have been in contact with patients with MDR-TB or XDR-TB. • All persons living with HIV and workers who are exposed to silica should always be screened for active TB in all settings. Other high-risk groups should be prioritised for screening based on the local TB epidemiology, health system capacity, resource availability and feasibility of reaching the risk groups. • CXR is an important tool for triaging and screening for pulmonary TB, and it is also useful to aid diagnosis when pulmonary TB cannot be confirmed bacteriologically. CXR can be used to select individuals for referral for bacteriological confirmation and the role of radiology remains important when bacteriological tests cannot provide a clear answer. Standards for TB diagnosis • All patients with signs and symptoms of pulmonary TB who are capable of producing sputum should have as their initial diagnostic test at least one sputum specimen submitted for Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra assay. This includes children who are able to provide a sputum sample and patients with EPTB. A second Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra assay may be performed for all patients who initially test negative by Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra but whose signs and symptoms of TB persist. • The Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra assay should be used in preference to conventional microscopy and culture as the initial diagnostic test for cerebrospinal fluid specimens from patients being evaluated for TB meningitis. The Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra assay is recommended as a replacement test for usual practice (including conventional microscopy, culture or histopathology) for testing specific nonrespiratory specimens (lymph nodes and other tissues) from patients suspected of having EPTB. • For persons living with HIV, the Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra assay should be used as an initial diagnostic test. LF-LAM can be used to assist in the diagnostic process for HIV-positive patients who are seriously ill. • DST using WHO-recommended rapid tests should be performed for all TB patients prior to starting therapy, including new patients and patients who require retreatment. If rifampicin resistance is detected, rapid molecular tests for resistance to isoniazid, fluoroquinolones and second-line injectable agents should be performed promptly to inform the treatment of MDR-TB and XDR-TB. • Culture-based DST for selected second-line anti-TB agents should be performed for patients enrolled in individualised (longer) MDR-TB treatment. Standard for diagnosing LTBI • Either TST or IGRA can be used to test for LTBI. TST is not required before initiating IPT in persons living with HIV. 40 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine NTP-MOP: • All presumptive TB should undergo DSSM unless it is not possible due to the following situations o mentally incapacitated as decided by a specialist or medical institution o debilitated or bedridden o children unable to expectorate o patients unable to produce sputum despite sputum induction Int’l Std for TB Care: • All patients, including children, who are suspected of having pulmonary tuberculosis and are capable of producing sputum should have at least two sputum specimens submitted for smear microscopy or a single sputum specimen for Xpert MTB/RIF testing in a quality-assured laboratory. Patients at risk for drug resistance, who have HIV risks, or who are seriously ill, should have Xpert MTB/RIF performed as the initial diagnostic test. Blood-based serologic tests and interferon-gamma release assays should not be used for diagnosis of active tuberculosis. 41 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine • • For all patients, including children, suspected of having extrapulmonary tuberculosis, appropriate specimens from the suspected sites of involvement should be obtained for microbiological and histological examination. An Xpert MTB/RIF test is recommended as the preferred initial microbiological test for suspected tuberculous meningitis because of the need for a rapid diagnosis. In patients suspected of having pulmonary tuberculosis whose sputum smears are negative, Xpert MTB/RIF and/or sputum cultures should be performed. Among smear- and Xpert MTB/RIF negative persons with clinical evidence strongly suggestive of tuberculosis, anti-tuberculosis treatment should be initiated after collection of specimens for culture examination. WHO Guidelines: • Sputum should be obtained, as well as appropriate specimens for culture and histopathological examination in cases of extrapulmonary TB, depending on the site of disease. Examination of sputum and a chest radiograph are also suggested, in case patients have concomitant pulmonary involvement. • For HIV-negative patients, if broad-spectrum antibiotics are used in the diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary TB, anti-TB drugs and fluoroquinolones should be avoided. A trial of broad-spectrum antibiotics is no longer recommended to be used as a diagnostic aid for smear-negative pulmonary TB in persons living with HIV. WHO 2018: Standards for HIV infection and other comorbid conditions • HIV testing should be routinely offered to all patients with presumptive TB and those who have been diagnosed with TB. • Persons living with HIV should be screened for TB by using a clinical algorithm. • ART and routine CPT should be initiated among all TB patients living with HIV, regardless of their CD4 cell count. • A thorough assessment should be conducted to evaluate comorbid conditions and other factors that could affect the response to or outcome of TB treatment. Particular attention should be given to diseases or conditions known to affect treatment outcomes, such as diabetes mellitus, drug and alcohol abuse, undernutrition and tobacco smoking. WHO 2018: Standards for treating drug-susceptible TB • While awaiting DST results, patients with drug-susceptible TB and TB patients who have not been treated previously with anti-TB agents and do not have other risk factors for drug resistance should receive a WHO-recommended firstline treatment regimen using quality assured anti-TB agents. The initial phase should consist of 2 months of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. The continuation phase should consist of 4 months of isoniazid and rifampicin. Daily dosing should be used throughout treatment. The doses of anti-TB agents should conform to WHO’s recommendations. FDC anti-TB agents may provide a more convenient form ofadministration. • In patients who require retreatment for TB, the category II regimen should no longer be prescribed and DST should be conducted toinform the choice of treatment regimen. • In patients with tuberculous meningitis or tuberculous pericarditis, adjuvant corticosteroid therapy should be used in addition to anappropriate TB treatment regimen. Standards for treating drug-resistant TB • In patients with rifampicin-susceptible, isoniazid-resistant TB, 6 months of combination treatment with rifampicin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide and levofloxacin, with or without isoniazid, is recommended. • Patients with MDR/RR-TB require second-line treatment regimens. MDR/RR-TB patients may be treated using a 9–11month MDR-TB treatment regimen (the shorter regimen) unless they have resistance to second-line anti-TB agents or meet other exclusion criteria. In these cases, a longer (individualised) regimen with at least five effective anti-TB agents in the intensive phase and four agents in thecontinuation phase is recommended for ⩾20 months. Partial resection surgery has a role in treating MDR-TB. Standard for treating LTBI • Persons living with HIV and children younger than 5 years who are household or close contacts of persons with TB and who, after anappropriate clinical evaluation, are found not to have active TB but to have LTBI should be treated. Disease Classification Based on Anatomical Site and Bacteriologic Status Anatomical Site Bacteriological status Definition of Terms Smear-positive Bacteriologicallyconfirmed Pulmonary (PTB) Clinicallydiagnosed Culturepositive Rapid Diagnostic Test-positive A patient with at least one (1) sputum specimen positive for AFB, with or without radiographic abnormalities consistent with active TB A patient with positive sputum culture for MTB complex, with or without radiographic abnormalities consistent with active TB A patient with sputum positive for MTB complex using rapid diagnostic modalities such as Xpert MTB/RIF, with or without radiographic abnormalities consistent with active TB A patient with two (2) sputum specimens negative for AFB or MTB, or with smear not done due to specified conditions but with radiographic abnormalities consistent with active TB; and there has been no response to a course of empiric antibiotics and/or symptomatic medications; and who has been decided (either by the physician and/or TBDC) to have TB disease requiring a full course of anti-TB chemotherapy OR 42 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Extrapulmonary (EPTB) Bacteriologicallyconfirmed Clinicallydiagnosed A child (less than 15 years old) with two (2) sputum specimens negative for AFB or with smear not done, who fulfills three (3) of the five (5) criteria for disease activity (i.e., signs and symptoms suggestive of TB, exposure to an active TB case, positive tuberculin test, abnormal chest radiograph suggestive of TB, and other laboratory findings suggestive of tuberculosis); and who has been decided (either by the physician and/or TBDC) to have TB disease requiring a full course of anti-TB chemotherapy OR A patient with laboratory or strong clinical evidence for HIV/AIDS with two (2) sputum specimens negative for AFB or MTB or with smear not done due to specified conditions but who, regardless of radiographic results, has been decided (either by physician and/or TBDC) to have TB disease requiring a full course of anti-TB chemotherapy. A patient with a smear/culture/rapid diagnostic test from a biological specimen in an extra-pulmonary site (i.e., organs other than the lungs) positive for AFB or MTB complex A patient with histological and/or clinical or radiologic evidence consistent with active extra-pulmonary TB and there is a decision by a physician to treat the patient with anti-TB drugs TB Disease Registration Groups Registration Group New Retreatment Relapse Treatment After Failure Treatment After Lost to Follow-up (TALF) Previous Treatment Outcome Unknown (PTOU) Other Definition of Terms A patient who has never had treatment for TB* or who has taken anti-TB drugs for less than one (<1) month. A patient previously treated for TB, who has been declared cured or treatment completed in their most recent treatment episode, and is presently diagnosed with bacteriologically-confirmed or clinically-diagnosed TB. A patient who has been previously treated for TB and whose treatment failed at the end of their most recent course.This includes: • A patient whose sputum smear or culture is positive at 5 months or later during treatment. • A clinically diagnosed patient (e.g., child or EPTB) for whom sputum examination cannot be done and who does not show clinical improvement anytime during treatment. A patient who was previously treated for TB but was lost to follow-up for two months or more in their most recent course of treatment and is currently diagnosed with either bacteriologically-confirmed or clinically-diagnosed TB. Patients who have been previously treated for TB but whose outcome after their most recent course of treatment is unknown or undocumented. Patients who do not fit into any of the categories listed above. Recommended Category of Treatment Regimen Category of Treatment Category I Category Ia Category II Category IIa Classification and Registration Group Pulmonary TB, new (whether bacteriologically-confirmed or clinically-diagnosed) Extra-pulmonary TB, new (whether bacteriologically-confirmed or clinically-diagnosed) except CNS/ bones or joints Extra-pulmonary TB, new (CNS/ bones or joints) Pulmonary or extra-pulmonary, previously treated drug-susceptible TB (whether bacteriologically confirmed or clinically-diagnosed) • Relapse • Treatment After Failure • Treatment After Lost to Follow-up (TALF) • Previous Treatment Outcome Unknown • Other Extra-pulmonary, Previously treated drug susceptible TB (whether bacteriologically confirmed or clinically diagnosed - CNS/ bones or joints) Standard Shorter MDR-TB Regimen (SSTR) RR-TB or MDRTB Standard Regimen Drug-resistant (SRDR) RR-TB or MDRTB Regimen for XDR XDR-TB Treatment Regimen 2HRZE/4HR 2HRZE/10HR 2HRZES/1HRZE/5HRE 2HRZES/1HRZE/9HRE 4-6 Km-Mfx-Pto-Cfz-Z-Hhigh-dose-E / 5 Mfx-Cfz-Z-E Treatment duration for at least 9-12 months ZKmLfxPtoCs Individualized once DST result is available Treatment duration for at least 18-24 months Individualized based on DST result and history of previous treatment Note: H=Isoniazid, R=Rifampicin, Z=Pyrazinamide, E=Ethambutol, S=Streptomycin 43 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine NTP-MOP: • DOT can be done in any accessible and convenient place for the patient (e.g., DOTS facility, treatment partner’s house, patient’s place of work, or patient’s house) as long as the treatment partner can effectively ensure the patient’s intake of the prescribed drugs and monitor his/her reactions to the drugs. Any of the following could serve as treatment partner: a) DOTS facility staff, such as the midwife or the nurse; or b) a trained community member, such as the barangay health worker (BHW), local government official, or a former TB patient. • Trained family members may be assigned to administer oral medications during weekends and holidays; or as the sole treatment partner in special/exceptional cases, such as: o Poor access to a DOTS facility due to geographical barriers (including temporarily displaced populations) o Debilitated and/or bed-ridden patients o DOT schedule is in conflict with the patient’s work/school schedule and unable to access other DOTS facilities o Cultural beliefs that limit the choice of a treatment partner (e.g., indigenous people) o Treatment of children • In such cases where a family member is the treatment partner, drug supply is to be distributed on a weekly basis or as agreed by the health worker and the family member. • Streptomycin intramuscular injections are to be administered only by trained and authorized health personnel. Patients with no access to such services during weekends/holidays may forego streptomycin doses during weekends/holidays provided they still complete the recommended number of doses (i.e., 56 doses). • A TB patient diagnosed during confinement in a hospital may start treatment using NTP drug supply upon the approval of the hospital TB team. Once discharged, the patient shall be referred by the hospital TB team to a DOTS facility for registration and continuation of the assigned standard treatment regimen. Treatment response is monitored through follow-up sputum exams – only 1 specimen required. The schedule generally follows this principle: follow-up DSSM shall be done at the end of intensive phase, at the end of the 5th month and at the end of treatment. Category I/Ia Category II /IIa Note:*If the patient belongs to Category I or Ia and baseline DSSM is negative, no need to repeat DSSM in succeeding months. **For Category I or Ia patients who remain positive after the intensive phase, follow the DSSM schedule of Category II patients without changing the treatment regimen. Int’l Std for TB Care: • Response to treatment in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis (including those with tuberculosis diagnosed by a rapid molecul ar test) should be monitored by follow up sputum smear microscopy at the time of completion of the initial phase of treatment (two months). If the sputum smear is positive at completion of the initial phase, sputum microscopy should be performed again at 3 monthsand, if positive, rapid molecular drug sensitivity testing (line probe assays or Xpert MTB/RIF) or culture with drug susceptibility testing should be performed. In patients with extra-pulmonary tuberculosis and in children, the response to treatment is best assessedclinically. • An assessment of the likelihood of drug resistance, based on history of prior treatment, exposure to a possible source case having drug-resistant organisms, and the community prevalence of drug resistance (if known), should be undertaken for all patients. Drug susceptibility testing should be performed at the start of therapy for all patients at a risk of drug resistance. Patients who remain sputum smear-positive at completion of 3 months of treatment, patients in whom treatment has failed, and patients who have been lost to follow up or relapsed following one or more courses of treatment should always be assessed for drug resistance. For patients in whom drug resistance is considered to be likely an Xpert MTB/RIF test should be the initial diagnostic test. If rifampicin resistance is detected, culture and testing for susceptibility to isoniazid, fluoroquinolones, and second-line injectable drugs should be performed promptly. Patient counseling and education, as well as treatment with an empirical second-line regimen, should begin immediately to minimize the potential for transmission. Infectioncontrol measures appropriate to the setting should be applied. • Patients with or highly likely to have tuberculosis caused by drug-resistant (especially MDR/XDR) organisms should be treated with specialized regimens containing quality-assured second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs. The doses of anti-tuberculosis drugs should conform to WHO recommendations. The regimen chosen may be standardized or based on presumed or confirmed drug susceptibility patterns. At least five drugs, pyrazinamide and four drugs to which the organisms are known or presumed to be susceptible, including an injectable agent, should be used in a 6–8 month intensive phase, and at least 3 drugs to which the organisms are known or presumed to be susceptible, should be used in the continuation phase. Treatment should be given for at least 18–24 months 44 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine beyond culture conversion. Patient-centered measures, including observation of treatment, are required to ensure adherence. Consultation with a specialist experienced in treatment of patients with MDR/XDR tuberculosis should beobtained. WHO Guidelines: • A positive smear at the end of intensive phase has a very poor ability to predict relapse or pretreatment isoniazid resistance. However, it is useful in detecting problems with patient supervision and for monitoring program performance. For smear-positive pulmonary TB patients (whether Category 1 or 2) treated with first-line drugs, sputum smear microscopyMAY be performedat completion of the intensive phase of treatment.Then for new cases, sputum smear microscopy is to be repeated at the end of the fifth and sixth months.However,if the specimen obtained at the end of the intensive phase (month 2) is smear-positive in new patients, sputum smear microscopy should be obtained at the end of the third month; and if it is still positive, sputum culture and drug susceptibility testing (DST) should be performed. This will allow a result to be available earlier than the fifth month of treatment.In previously treated patients, sputum culture DST should be performed if follow-up smear after the intensive phase is positive. In patients treated with the regimen containing rifampicin throughout treatment, if a positive sputum smear is found at completion of the intensive phase, the extension of the intensive phase is not recommended. • If a patient is found to harbour a multidrug-resistant strain of TB at any time during therapy, treatment is declared a failure and the patient is re-registered and should be referred to an MDR-TB treatment programme.It is unnecessary, unreliable and wasteful of resources to monitor the patient by chest radiography. Pulmonary TB patients whose sputum smear microscopy was negative (or not done) before treatment and whose sputum smears are negative at 2 months need no further sputum monitoring. They shoul d be monitored clinically; body weight is a useful progress indicator. For patients with extrapulmonary TB, clinical monitoring is the usual way of assessing the response to treatment. Int’l Std for TB Care: • HIV testing and counseling should be conducted for all patients with, or suspected of having, tuberculosis unless there is a confirmed negative test within the previous two months. Because of the close relationship of tuberculosis and HIV infection, integrated approaches to prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of both tuberculosis and HIV infection are recommended in areas with high HIV prevalence. HIV testing is of special importance as part of routine management of all patients in areas with a high prevalence of HIV infection in the general population, in patients with symptoms and/or signs of HIV-related conditions, and in patients having a history suggestive ofhigh risk of HIV exposure. • In persons with HIV infection and tuberculosis who have profound immunosuppression (CD4 counts less than 50 cells/mm3), ART should be initiated within 2 weeks of beginning treatment for tuberculosis unless tuberculous meningitis is present. For all other patients with HIV and tuberculosis, regardless of CD4 counts, antiretroviral therapy should be initiated within 8 weeks of beginning treatment for tuberculosis. Patients with tuberculosis and HIV infection should also receive co-trimoxazole as prophylaxis for other infections. • Persons with HIV infection who, after careful evaluation, do not have active tuberculosis should be treated forpresumed latent tuberculosis infection with isoniazid for at least 6 months. • All providers should conduct a thorough assessment for co-morbid conditions and other factors that could affect tuberculosis treatment response or outcome and identify additional services that would support an optimal outcome for each patient. These services should be incorporated into an individualized plan of care that includes assessment of and referrals for treatment of other illnesses. Particular attention should be paid to diseases or conditions known to affect treatment outcome, for exampl e, diabetes mellitus, drug and alcohol abuse, undernutrition, and tobacco smoking. Referrals to other psychosocial support services or to such services asantenatal or well-baby care should also be provided. • All providers should ensure that persons in close contact with patients whohave infectious tuberculosis are evaluated and managed in line with internationalrecommendations. The highest priority contacts for evaluation are: o Persons with symptoms suggestive of tuberculosis o Children aged <5 years o Contacts with known or suspected immunocompromised states,particularly HIV infection o Contacts of patients with MDR/XDR tuberculosis 45 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine WHO Guidelines: • The first priority for HIV-positive TB patients is to initiate TB treatment, followed by co-trimoxazole and ART. • Drug susceptibility testing is now recommended at the start of TB therapy in all people living with HIV, to avoid mortality due to unrecognized drug-resistant TB), and strongly encourages the use of rapid DST in sputum smear-positive persons living with HIV. Treatment Outcomes for Drug-susceptible TB Cases Outcome Cured Treatment completed Treatment failed Died Lost to follow-up Not Evaluated Definition A patient with bacteriologically-confirmed TB at the beginning of treatment and who was smear- or culture-negative in the last month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion in the continuation phase. A patient who completes treatment without evidence of failure but with no record to show that sputum smear or culture results in the last month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion were negative, either because tests were not done or because results are unavailable.This group includes: • A bacteriologically confirmed patient who has completed treatment but without DSSM follow-up in the last month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion • A clinically diagnosed patient who has completed treatment A patient whose sputum smear or culture is positive at 5 months or later during treatment. OR A clinically diagnosed patient (child or EPTB) for whom sputum examination cannot be done and who does not show clinical improvement anytime during treatment. A patient who dies for any reason during the course of treatment. A patient whose treatment was interrupted for 2 consecutive months or more. A patient for whom no treatment outcome is assigned. This includes cases transferred to another DOTS facility and whose treatment outcome is unknown. LECTURE 8 : SLEEP RELATED BREATHING DISORDERS 46 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA (OSA) INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Discuss respiratory physiology during sleep 2. Recognize the symptoms attributable to a sleep related disorder of breathing 3. Present the clinical evaluation of a patient with SDB 4. Describe the natural course of the disease and the systemic consequences 5. Discuss options for treatment 5.1. lifestyle changes 5.2. oral appliances 5.3. continuous positive airway pressure 5.4. surgical options Physiologic Impact of sleep on breathing • minimal in normal individuals • significant consequences in those with disturbances of respiratory structure or function o decreased metabolic drive o decreased diaphragmatic strength o decreased intercostal and accessory muscle function activity (in those with structurally small oropharynx) Sleep Disordered Breathing (SDB) • Apnea: Cessation of airflow for at least 10 seconds • Hypopnea: Reduction in airflow with resultant desaturation of ≥4% Definitions of SDB • Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI): Averaged frequency of apnea and hypopnea events per hour of sleep Types of Sleep Studies • Type I -in-laboratory, technician-attended, overnight polysomnography (PSG) • Type II -can perform full PSG outside of the laboratory without a technologist • Type III -do not record the signals needed to determine sleep stages or sleep disruption • Type IV -continuous single or dual bioparameter devices Obstructive Sleep Apnea • AHI or RDI ≥15 from portable monitors • AHI or RDI ≥5 and associated with symptoms (excessive daytime sleepiness, impaired cognition, mood disorders, insomnia, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, or history of stroke) • The presence of respiratory efforts during these events suggests that they are predominantly obstructive Treatment • Oral appliance • CPAP • Surgical approach • Medications • Risk factor directed treatments (weight reduction, sleep hygiene) REFERENCES: 47 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 20th Edition Principles of Sleep Medicine, Kryger, Roth and Dement, 4 th Edition NOTES: 48 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine LECTURE 9 : LUNG CANCER INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Enumerate the risk factors in the development of lung cancer 2. Discuss the etiopathogenesis of lung cancer 3. Present an algorithm in the evaluation of patient with lung cancer 4. Discuss the advances in the diagnosis and staging of Lung Cancer 5. Discuss the standard treatment of Non-Small Cell and Small Cell Lung Cancer 6. Elaborate on the role of palliative care in the management of patient with Lung Cancer vis-à-vis standard treatment Lung Cancer Lung cancer causes 1.37 million deaths per year worldwide, which represents 18% of all cancer deaths. Within the European Union, lung cancer is the most frequently fatal cancer, leading to over 266,000deaths yearly and accounting for 20.8% of all cancer deaths. Definitive surgery in the early stages is themost effective treatment for lung cancer. However, most patients are diagnosed at an advanced, and thusnon-curable, disease stage. Survival time decreases significantly with progression of disease, with a 5-yearsurvival time declining from 50% for clinical stage IA to 43%, 36%, 25%, 19%, 7% and 2% for stages IB, IIA, IIB, IIIA, IIIB and IV, respectively. Moreover, Shi et al.reported a 5-year survival rate of morethan 80% in 185 surgically treated patients with peripheral smallsized lung cancers (2 cm or less) afterlobectomy and lymph node dissection. In particular, the 5-year survival rate increased with smallertumour size: 80% in tumours1.6–2.0 cm, 85% in tumours 1.0–1.5 cm and 100% in tumours<1.0 cm indiameter, respectively. It is 49 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine therefore crucial to detect lung cancer early, before symptoms occur and whilecurable therapy is still achievable. 50 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine REFERENCES: ESR/ERS Lung Cancer White Paper April 2015. American Cancer Society. AJCC Lung Cancer Staging 8th Edition. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 20thEdition American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Lung Cancer (2nd Edition). Chest 2007: 132 Clinical Practice Guidelines in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Lung Cancer, UST Benavides Cancer Institute, Thoracic Unit (2007) 51 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine LECTURE 10 : VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM (VTE) INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Define burden of illness and provide a clear definition of terms: Deep vein thrombosis (DVT), Pulmonary Embolism (PE) and VTE 2. Enumerate the risk factors (Virchow’s Triad) for the development of VTE and cite predisposing clinical conditions. 3. Discuss the etiopathogenesis of VTE (formation of blood clots from the leg veins to the lungs) and its consequences on the cardiorespiratory system. 4. Enumerate the clinical manifestations of DVT-PE 5. Discuss the objective evaluation and diagnostic work-up for DVT-PE 5.1. applying the "clinical decision/prediction rule" (Well’s Criteria) 6. Discuss briefly the current and recommended management for VTE using: 6.1. Pharmacologic modalities: a) anticoagulants e.g. heparins (UFH, LMWH), warfarin, pentassacharides; b) thrombolytics; c) new oral anticoagulants (NOA) 6.2. Non-pharmacologic modalities eg. IVC filter, IPC, GCS, and anti-embolic stockings (AES). 6.3. PROPHYLAXIS using either pharmacologic or non-pharmacologic REFERENCES: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 21st Edition Textbook of Respiratory Medicine 5th edition. Murray-Nadel, 2021; 7th Edition Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 2nd Update to 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians EvidenceBased Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest August 2021 Wells (2001) Annals of Intern Med, 135: 98-107; July 2001 NOTES: 52 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine 1. DEFINITION • • • • Venous Thromboembolism Venous thromboembolism (VTE) includes deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). Pulmonary Embolism (PE)- a complication of an underlying disease ▪ It commonly results from venous thrombosis occurring in the deep veins of the lower extremities. It is the number one preventable cause of death in the hospital.1,2 The incidence of VTE in Asia is perceived to be low compared to Western countries. However, Asian studies report an incidence of fatal PE ranging from 0.2% to 6%.3 Basic risk factors- Virchow’s triad-stasis, hypercoagulability, and Intimal wall or endothelial injury. 2. ETIOLOGY – ETIOPATHOGENESIS • • • • • • Venous thrombi start to form either in the vicinity of a venous valve, where eddy currents arise, or at the site of intimal injury. Platelets start to aggregate with release of mediators that initiate the coagulation cascade, causing the formation of a red thrombus. At any time during the formation of a venous thrombus, a portion or all of the thrombus can detach as an embolus. Once embolism occurs, it can trigger very serious pulmonary and cardiac effects (impaired gas exchange; increased pulmonary vascular resistance), depending on the extent of the reduction of the cross sectional area of the pulmonary vascular bed as well as the preexisting status of the cardiopulmonary system. Over 90 percent of cases of acute PE are due to emboli emanating from the proximal veins of the lower extremities. Thrombus formed above the popliteal vein e.g. iliofemoral,(above-the-knee, thigh or proximal thrombi) appear to be the source of most clinically recognized pulmonary embolus. 3.CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS • • • • • • Dyspnea / tachypnea Syncope, hypotension or cyanosis indicates a massive PE Pleuritic pain, cough, or hemoptysis- small embolism located distally near the pleura. Physical examination- non specific; may have tachypnea and tachycardia, accentuated P2 component of S2; recent onset RVH; elevated JVP No clinical findings are universal and the absence of specific findings does not rule out the diagnosis. Wells Criteria relies on a carefully taken history and physical examination which consists of seven variables, namely: (see Appendix) 1-signs-symptoms of DVT 2-PE more likely than alternative diagnosis 3-tachycardia (>100 bpm) 4-surgery or immobilization in last 4 weeks 5-prior DVT or PE 6-hemoptysis 7-active malignancy 4. LABORATORY/ANCILLARY PROCEDURES (see algorithm in Appendix) • • • Blood tests ▪ A complete blood count(CBC)– may show leukocytosis. ▪ Arterial blood gases (ABGs)–may reveal low oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. ▪ new generation D-dimer assay in combination with the Wells clinical prediction rule is effective in ruling out clinically significant PE. A negative test using the ELISA technique (e.g. Vidas d-dimer less than 500 ng/ml) may rule out PE in patients with a low to moderate pretest probability and a nondiagnostic VQ scan. Electrocardiography –tachycardia and nonspecific ST-T wave changes. ▪ classic finding of an “S1-Q3-T3” pattern is observed in only 20% of patients with proven PE. Chest radiography –nonspecific, may be normal 53 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine • • • • • • • • • ▪ A peripheral wedge shaped infiltrate (Hampton’s hump)- PE with infarction ▪ Localized decrease in pulmonary vascular markings (Westermark’s sign) Ventilation-Perfusion Lung Scan – A normal perfusion lung scan virtually excludes PE ▪ high probability lung scan indicates a high likelihood of emboli (95 percent) particularly in patients with a high pretest probability of pulmonary emboli. Magnetic Resonance –sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 96% for central, lobar, and segmental emboli. ▪ inadequate for the diagnosis of subsegmental emboli. Echocardiography –can be used to rule out AMI, tamponade, aortic dissection. ▪ Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can show indirect evidence of PE in 80% of patients with massive PE and central emboli in 70% of cases. Computed Tomography - can visualize the main, lobar, and segmental pulmonary emboli with a reported sensitivity of >90%. CT Pulmonary angiography – remains the gold standard for diagnosis and will be needed in up to 20 percent of patients with suspected PE and inconclusive noninvasive evaluations. A positive result consists of a filling defect or sharp cutoff of small vessels. A negative test appears to exclude clinically relevant PE. Leg studies Contrast venography – has long been considered the "gold standard" for the diagnosis of DVT (MRA is emerging as a safe and reliable imaging test for both PE and DVT). In a study of 160 patients suspected clinically of having DVT in whom contrast venography was negative, only 1.3 % developed DVT during a six month follow-up. Impedance plethysmography(IPG) – a noninvasive test which measures venous outflow from the lower extremity and can detect proximal vein thrombosis with sensitivity and specificity of 91 and 96 percent, respectively. The IPG has been well validated against the gold standard. Detection of calf vein thrombosis is poor. Duplex scan – is the most widely used modality for evaluating patients with suspected DVT. Also known as Color-flow Doppler imaging or Compression ultrasonography (CU), this noninvasive test is operator dependent and does not distinguish between old from new clot. In one study of consecutive outpatients with clinically suspected DVT, CU had a sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 99%, respectively. Like all tests, ultrasonography for DVT is most useful when the results are combined with an assessment of pretest probability. 5.MANAGEMENT PHARMACOLOGIC Anticoagulants- main treatment regimen; administered to avoid further clot formation in the lower extremities ▪ Unfractionated heparin (UFH) IV or SQ- initial drug of choice o bolus of 80 IU/kg IV and maintenance infusion at 18 IU/kg. o duration is usually 7-10 days (5 days is just as effective o partialthromboplastin time (aPTT) of the patient maintained between 2-3 times the upper limit of the laboratory normal ▪ Oral anticoagulation with warfarin - may be started on the first day of heparin therapy (usual overlap is 3 - 5 days, as full effect of warfarin requires 5 days. o Prothrombin time (PT) should be monitored and the international normalized ratio (INR) target of 2.5, with a range of 2.0-3.0. ▪ Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH)e.g. enoxaparin. o Recommended dose is 1 mg/kg of given subcutaneously every 12 hours for up to 3 months in VTE patients with reversible risk factors. o For recurrent emboli and nonreversible risk factors, therapy may have to be given indefinitely. o less bleeding complications from LMWH than UFH Thrombolytic Therapy • Streptokinase, Urokinase, and recombinant Tissue Plasminogen activator (rTPA). • accelerate the resolution of the pulmonary artery clot and may be used especially in patients with massive embolism and systemic hypotension. • must be followed by a standard course of heparin treatment • increased incidence of bleeding. Newly developed anticoagulant/Antithrombotic Drugs. • Most are monotherapeutic(specific factor Xa inhibitors e.g.Fondaparinux) in contrast to the LMWH which are polytherapeutic. 54 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine New oral anticoagulants (NOAC) • Dabigatran, and rivaroxaban have already been approved for prophylaxis after hip and knee surgery in the US while, apixaban has been approved in Europe; Rivaroxaban have been approved for VTE treatment as well Non-Pharmacologic • IVC filter, intermittent pneumatic compression device (IPC), graduated compression stockings (GCS), and antiembolic stockings (AES). • Inferior vena cava (IVC) interruption, via filter placement may be used as an alternative therapy for VTE when absolute contraindications (eg, recent surgery, hemorrhagic stroke, or significant active or recent bleeding) or failure of anticoagulation are present. 6. PROPHYLAXIS Pharmacologic • Unfractionated heparin –SQ, every 8 hrs; needs aPTT monitoring • Low molecular weight heparin –for both prophylaxis and treatment of patients who present primarily with DVT with or without concomitant PE. o Dalteparin and fondaparinux was approved for prophylaxis only but not VTE treatment. Fondaparinux- Factor Xa inhibitor, pentasaccharide, given for prophylaxis medical patients at 2.5 mg/ subcutaneous q 24hours. Rivaroxaban- FactorXa inhibitor given for prophylaxis in patient who underwent orthopedic surgery; dose 10mg/tab per orem once a day. Non-pharmacologic • Early ambulation, especially for post-operative patients. • Graduated elastic compression stockings – provide pressure on the lower extremities, to prevent venous stasis. • Intermittent pneumatic compression – is a mechanical device attached to the extremities, which provides some form of passive leg exercises, therefore stimulating muscle contraction. • Inferior vena caval interruption – a most popular and widely used device is the Greenfield filter. APPENDIX: ❖ VTE Diagnostic Algorithm (A Practical Approach) Suspect DVT or PE Assess Clinical probability (Wells or Geneva criteria) DVT Low-Mod PE High D-dimer D-dimer ELISA or Latex Normal no DVT High Low-Mod ELISA or Latex Increased do ImagingDuplex Normal Increased do ImagingCTPA or VQ no PE th *Algorithm modified by Dr. Villespin from Harrison’s Internal Med 18 ed. 2011_Feb 14, 2013 55 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine I. Wells scoring system for DVT CLINICAL VARIABLE Score Active Cancer 1 Paralysis, paresis, or recent cast 1 Bedridden >3d; major surgery <12 weeks 1 Localized tenderness along the deep veins 1 Unilateral calf swelling>3cm Unilateral pitting edema Collateral superficial nonvaricose veins Alternate dx at least as likely than DVT 1 1 1 -2 Original criteria: (Lancet, 1997; 350: 1795-98) Score < 1 point 1-2 points > 3 points Risk Low probability Moderate probability High probability Probability of DVT 3% 17% 75% Simplified Criteria: (CMAJ, 2006) 1 point- DVT is likely < 1 point- DVT is unlikely II. A. Wells Score for PE CLINICAL FEATURE Signs &Sx of DVT PE most likely dx Hear rate >100 Immobilzation or surgery 4 wks prior Previous DVT or PE Hemoptysis Active Cancer Total Points 3.0 3.0 1.5 1.5 1.5 1.0 1.0 12.5 Wells Criteria for PE (Original, 3-tiered) Risk Points % Patients with these features Probability of PE (%) Low 0-2 40 3.6 Moderate ate 3 - 6 53 20.5 High >6 7 66.7 Wells’ Criteria: (Modified, 2-tiered) > 4 PE is likely ≤ 4 PE is unlikely 56 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine II. B. Geneva Score(Original, 3-tiered)) The original Geneva score is calculated using 7 risk factors and clinical variables: Variables • • Score Age 60 - 79 years 1 80+ years 2 Previous venous thromboembolism Previous DVT or PE • 2 Previous surgery Recent surgery within 4 weeks • 3 Heart rate Heart rate >100 beats per minute • • • • • • 1 PaCO2 < 35mmHg 2 35 – 39 mmHg 1 PaO2 < 49 mmHg 4 49 – 59 mmHg 3 60 – 71 mmHg 2 72 – 82 mmHg 1 Chest X-ray Plate-like atelectasis 1 Elevation of hemidiaphragm 1 < 5 points indicates a low probability of PE 5 - 8 points indicates a moderate probability of PE > 8 points indicates a high probability of PE Risk Points Low Moderate High 0-4 5-8 9 - 12 % Patients with Probability of PE these features (%) 49 44 6 10 38 81 EMERGENCY : 57 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine EMERGENCY : RESPIRATORY FAILURE / ARDS INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Define acute respiratory failure and ARDS 2. Recognize signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure and Acute respiratory distress syndrome 3. Discuss approach to patients with ARF and ARDS REFERENCES: Handbook of Medical and Surgical Emergencies, UST Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 21st Edition NOTES: 58 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine EMERGENCY : HEMOPTYSIS INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Define massive hemoptysis 2. Enumerate etiology and differential diagnosis for patients presenting with massive hemoptysis 3. Discuss approach to patients with massive hemoptysis Definition Hemoptysis is defined as the expectoration of blood from the respiratory tract. Massive hemoptysis is variably defined as the expectoration of 100-600 mL o blood over a 24 hour period. Varied conditions may present with hemoptysis such as bronchitis, pneumonia, tuberculosis or bronchogenic carcinoma. Etiology Blood may originate from the nasopharynx or the gastrointestinal tract. If the blood is dark red in appearance with an acidic pH it is a clue that its origin is the GI tract. True hemoptysis is bright red in appearance and alkaline in pH. Differential Diagnosis Source other than the lower respiratory tract Upper airway bleeding GI bleeding Tracheobronchial source Neoplasm Bronchitis Bronchiectasis Foreign body Pulmonary parenchymal source Lung abscess Pneumonia TB Lupus pneumonitis Pulmonary vascular source AV malformation Pulmonary embolism Miscellaneous Pulmonary endometriosis Systemic coagulopathy 59 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Approach to a patient with Hemoptysis REFERENCES: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 21st Edition Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine 60 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine EMERGENCY : MASSIVE PULMONARY EMBOLISM INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Define massive pulmonary embolism. 2. Utilize algorithms in the diagnosis of massive pulmonary embolism. 3. Discuss the use of thrombolytic therapy in massive pulmonary embolism. Massive pulmonary embolism is defined as an acute pulmonary embolism(PE) with sustained systemic arterial hypotension.1 Proposed definition according American Heart Association is acute PE with sustained hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg for at least 15 minutes or requiring inotropic support, not due to a cause other than PE, such as arrhythmia,hypovolemia, sepsis, or left ventricular [LV] dysfunction), pulselessness, or persistent profound bradycardia (heart rate <40 bpm with signs or symptoms of shock).1Of the number of cases of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE), 10% is estimated to be classified as massive pulmonary embolism.2 This makes it pertinent to be able to diagnose and manage massive PE adequately. Only confirmed venous thromboembolism should receive thrombolytic therapy since this is coupled with major risks. Thrombolytics in addition to heparin anticoagulation as treatment for Massive PE requires individualized assessment of the balance of benefits versus risks.2 Potential benefits include rapid resolution of symptoms (eg, dyspnea, chest pain, and psychological distress), stabilization of respiratory and cardiovascular function without need for mechanical ventilation or vasopressor support, reduction of RV damage, improved exercise tolerance, prevention of PE recurrence, and increased probability of survival. Risks include disabling or fatal hemorrhage in the form ofintracerebral hemorrhage, and increased risk of minor hemorrhage, which results in prolonged hospital stay and need for blood transfusions.2Once it is decided that thrombolytic therapy is warranted, it is recommended that the thrombolytic agent be administered by a peripheral venous catheter, rather than a pulmonary arterial catheter (Grade 2C). The thrombolytic regimen infusion time should be short (ie, ≤2 hours), rather than a regimen with a more prolonged infusion time (Grade 2C).1 Aside from medical management, either catheter embolectomy and fragmentation or surgical embolectomy is reasonable for patients with massive PE and contraindications to fibrinolysis (Class IIa; Level of Evidence C). Offering these would depend upon the expertise of the medical institution.1Another indication for catheter embolectomy and fragmentation or surgical embolectomy is in massive PE who remain unstable after receiving fibrinolysis (Class IIa; Level of Evidence C). 2 REFERENCES: 1 Christophe Marti et al. Eur Heart J 2015;36:605-614 2Jaff, M. et al. Circulation. 2011; 123: 1788-1830 3Vyas and Donato& Thrombolysis in Acute Pulmonary Thromboembolism Southern Medical Journal & Volume 105, Number 10, October 2012 4Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012; 141:e419S. 61 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine WORKSHOP : WORKSHOPS 1 : CLINICO-RADIOLOGIC CORRELATION INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Interpret chest radiographs using ATMLL approach 2. Correlate the radiographic findings with historical data and physical examination findings with emphasis on IPPA 3. Recommend initial management 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Emphysema Pneumothorax Consolidation Obstructive Atelectasis Cicatricial Atelectasis Effusion Cavitary TB Bronchiectasis Metastatic lesions Clinico-Radiologic Correlation Are There Many Lung Lesions? A 1. costophrenic sulci 2. contour of hemidiaphragm 3. level of hemidiaphragm (R usually higher than left) T 1. symmetry of thoracic cage / ICS 2. rib fractures M 1. trachea 2. heart 3. hilar (L usually higher than left) LL 1. compare one lung to the other lung Emphysema A – flat/depressed hemidiaphragm; low set T – widened interspaces M – dropped heart – investigate for Pulmonary hypertension (look at Pulmonary arteries) LL – hyperluscent lungs, +/- bullae, pruning of blood vessels 62 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Pneumothorax A – +/- flattening of one hemidiaphragm on the side of the pathology; +/- blunting of costophrenic sulcus (secondary to bleeding) T – +/- widened interspaces on affected side M – +/- shifting of midline structures contralaterally LL – presence of visible visceral pleural line- radiographic hallmark Consolidation A T M LL – may be normal – normal – +/- silhouette sign depending on the lobe involvement – presence of air bronchograms Obstructive Atelectasis A – hemidiaphragm may be affected depending on the size of atelectasis T – +/- narrowed interspaces on affected side with compensatory widening on opposite side M – +/- shifting of midline structures ipsilaterally LL – homogenous opacification of affected area Cicatricial Atelectasis A – hemidiaphragm may be affected depending on the size of atelectasis T – +/- narrowed interspaces on affected side with compensatory widening on opposite side M – +/- shifting of midline structures ipsilaterally LL – inhomogenous opacification of affected area, with air bronchograms Effusion A – blunting of costophrenic sulcus, or non visualization of hemidiaphragm, due to presence of fluid T – +/- widened interspaces on affected side (may be hard to visualize because of the presence of fluid) M – +/- shifting of midline structures contralaterally depending on amount of fluid as well as presence of any other underlying lung pathology LL – homogenous opacification with a lateral upward curve (meniscus sign) -on lateral decubitus view – the homogenous density (fluid) occupies the most dependent portion of the chest wall (layering) if it is FREE within the pleural space Cavitary Tuberculosis A T M LL – costophrenic sulci not affected unless there is concomitant effusion or thickening – interspaces not affected unless there is also volume loss/ atelectasis – +/- shifting of midline structures depending on volume loss – lucency within the lung parenchyma usually with an irregular margin. Bronchiectasis A T M LL – costophrenic sulci not affected unless there is concomitant effusion or thickening – interspaces not affected unless there is also volume loss/ atelectasis – +/- shifting of midline structures depending on volume loss – honeycomb densities 63 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Metastatic lesions A T M LL – costophrenic sulci not affected unless there is concomitant effusion or thickening – interspaces not affected unless there is also volume loss/ atelectasis – +/- shifting of midline structures depending on volume loss – cannon ball appearance; brocnhoalveolar spread; multiple nodules Insp +/- lagging Palp Inc TF Perc Dull Auscult Inc BS Bronchophony, egophony, whispered pectoriloquy shift None Obstructive atelectasis +/- lagging Dec TF Dull Dec BS Ipsi Pleural effusion +/- lagging Dec TF Dull Dec BS Contra Pneumothorax +/- lagging Dec TF Hyper resonant Dec BS Contra Emphysema Minimal chest movement Dec TF Hyper resonant Dec BS bilaterally None Cicatricial atelectasis +/- lagging Inc TF Dull Inc BS Ipsi Consolidation NOTES: 64 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine WORKSHOP 2 : ABG / CLINICO-RADIOLOGIC CORRELATION INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Learn the usefulness of the arterial blood gas 2. Know the normal values 3. Interpret arterial blood gases 4. Present a simple algorithm in the interpretation of ABG results 5. Apply various equations to blood gas interpretation and clinical management Mechanics: The students will be divided into 3 groups. Each facilitator will discuss the 2 cases of ABG with the chest x-rays. CASE 1 A 79 y.o male, smoker came in because of dyspnea. There was use of accessory muscles of respiration. BP 120/80 CR 90/min RR 14/min. ABG RESULT: (at 4 LPM oxygenation) 7.33 63 100 29 98 78 0.56 278 0.26 QUESTIONS: 1. Interpret the ABG. Look at – a. pH b. PCO2 c. PaO2 d. HCO3 ANSWER: 2. Is the patient hypoxemic? ANSWER: 3. What is the oxygenation status? a. P/F ratio of the patient? b. Expected P/F of the patient? c. a/A pAO2 = 713 x FiO2 – pCO2/0.8 65 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine pAO2 = a/A = paO2/pA02 ANSWER: a/A = d. AaDO2 AaDO2 = pAO2 – paO2 AaDO2 = 4. What is the cause of the hypoxemia? (Refer to the algorithm) CASE 2 A 60 y.o male was rushed to the emergency room because of 3 day history of dyspnea, increased cough and sputum production. He had BP 130/80mmHg, HR 110 regular, RR 32, T 36.6C, oxygen saturation 70% at room air. He had supraclavicular retractions, paradoxical breathing and peripheral cyanosis, rhonchi and wheezes on both lung fields. He was intubated and hooked to the mechanical ventilator with the following set up: TV 400, RR 12 (with actual RR of 25) FIO2 of 50%. Chest x-ray done one day ago (show xray to students, ask them to 1. Interpret using ATMLL: Diagnosis: ______________________ 2. A – T – M – LL – What are the expected IPPA findings? Insp Palp Perc Auscult 3. Explain PE based on sound transmission principles 4. What in the cxr is pathognomonic of lobar consolidation? 5. What is the most common organism involved? shift 66 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine ABG RESULT: (at 50% FIO2) QUESTIONS: 1. Interpret the ABG. Look at – a. pH b. PCO2 c. PaO2 d. HCO3 ANSWER: 2. What is the oxygenation status? a. P/F ratio of the patient? ANSWER: b. Expected P/F of the patient? ANSWER: c. a/A pAO2 = 713 x FiO2 – pCO2/0.8 ANSWER: d. AaDO2 AaDO2 = pAO2 – paO2 AaDO2 = ANSWER: 3. What is the desired Fio2 of this patient? dFio2 = expected pO2 + pCO2 a/A 0.8 713 67 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine dFiO2 = = ANSWER: 4. How would we correct the hypoventilation? Remember: ● ● ● VA = Ve - Vd ● Ve = Vt x RR ANSWER: 5. Which caused the hypoxemia of the patient? a. Shunt b. Hypoventilation plus another mechanism c. VQ mismatch d. Diffusion ANSWER: 68 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Reference: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 19thEdition Notes: 69 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine 70 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine ARTERIAL BLOOD GAS MAIN INDICATIONS 1. to know the ventilatory status of the patient (acid base balance) 2. to know the oxygenation status of the patient 1. Ventilatory status / acid base • pH pCO2 • HCO3 2. Oxygenation status a. PaO2 b. O2 sat c. aAO2 d. p(A-a)O2 e. P/F IMPORTANT EQUATIONS: 1. Henderson - Hasselbach pH= 6.1 + log HCO3 / PaCO2 x 0.03 2. Alveolar Equation VA = VCO2 / PaCO2 x K VA = 1 / PaCO2 3. Alveolar Gas Equation PAO2 = FiO2 (PB – PH2O) – PACO2 / R PAO2 = FiO2 (713) – PACO2 / 0.8 4. Alveolar–arterial oxygen difference normal p(A-a)O2 = 15 +/- 5 torr P(A-a)O2 P(A-a)O2 = PAO2 – PaO2 PAO2 is computed for using equation #3 PaO2 is derived from ABG results 5. Arterial alveolar ratio aAO2 normal aAO2 = 0.75 PaO2 is derived from the ABG result PAO2 is computed for using equation #3 6. P/F ratio PaO2 / FiO2 PaO2 is derived from the ABG result FiO2 is the fraction of inspired oxygen being given to the patient Normal values for patients < 60 y.o. for patients > 60 y.o. expectedP/F = 400 expected P/F = 400 – (years above 60 x 5) 7. LPMto FiO2 8. Desired FiO2 LPM x 4 + 20 - compute for PAO2 (equation # 3) - compute for aAO2 (equation # 5) - compute for desired FiO2 desired PaO2* + aAO2 PaCO2 0.8 desired FiO2 = 713 • desired PaO2 is usually 80-100 71 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine INTERPRETING THE ARTERIAL BLOOD GAS 1. IS THE ABG NORMAL OR ABNORMAL? Normal values: pH 7.35 – 7.45 pCO2 35- - 45 pO2* 80 – 100 HCO3 22 – 27 O2 sat > 95% 2. IF THE ABG IS NORMAL, GREAT! 3. IF THE ABG IS ABNORMAL, PROCEED WITH INTERPRETATION OF THE ACID BASE BALANCE AND OXYGENATION VENTILATORY/ ACID BASE STATUS 1. Is the problem ACIDEMIA or ALKALEMIA? pH< 7.4 = acidemia pH> 7.4 = alkalemia 2. Is the primary disturbance RESPIRATORY or METABOLIC? • correlate the pH with the pCO2 and HCO3 • a high pCO2 leads to acidemia, while a low pCO2 leads to alkalemia • a high HCO3 leads to alkalemia, while a low HCO3 leads to acidemia 3. Is it UNCOMPENSATED, PARTIALLY, OR FULLY COMPENSATED? Respiratory acidosis Alkalosis Metabolic acidosis Alkalosis Primary disturbance high pCO2 low pCO2 Compensation HCO3 will increase HCO3 will decrease low HCO3 high HCO3 pCO2 will decrease pCO2 will increase UNCOMPENSATED - there is no movement of either the pCO2 or the HCO3 in response to the primary disturbance PARTIALLY COMPENSATED - there is movement of the pCO2 or HCO3 in an attempt to correct the primary disturbance, but the movement is not enough to normalize the pH COMPENSATED - there is movement of the pCO2 of HCO3 to correct the primary disturbance, and the increase or decrease is enough to normalize the pH 72 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine OXYGENATION STATUS 1. Is the patient HYPOXEMIC? • a normal pO2 DOES NOT MEAN that there is no hypoxemia in a patient on supplemental oxygen • the other indices of oxygenation have to be considered • any time a patient has a pO2 > 100, he is probably receiving supplemental oxygen OXYGENATION AT ROOM AIR FiO2 = 21% 1. patients< 60 y.o. expected PaO2 = 80 – 100 2. patients> 60 y.o. expected PaO2 = 80 – years above 60 3. compare PaO2 value in ABG to the expected 4. if actual < expected, patient is hypoxemic ON SUPPLEMENTAL OXYGEN 1. check aAO2, p(A-a)O2 and P/F ratio expected aAO2 > 0.75 expected p(A-a)O2 = 15 + 5 expected P/F for patients < 60 years old = 400 for patients > 60 years old = 400 – (yrs above 60 x 5) 2. Is the patient receiving the desired FiO2?- compute for desired FiO2 using equation #8 in previous page 73 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine WORKSHOP 3: SPIROMETRY / INHALER GADGETS / PEAK FLOW STATION 1: SPIROMETRY INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: At the end of the session the participants will: 1. Know how a spirometry test is performed. 2. Be able to generate a good spirometry test. 3. Be able to discern whether a spirometry test is of good quality. Acceptability Criteria: 1. Good start (extrapolated volume < 150 ml) 2. Good end [FET > 6 sec. & Plateau (< 25 ml/ sec)] 3. No artifacts (smooth curve) Reproducibility Criteria: 1. There should be at least 3 acceptable trials 2. Two largest acceptable FVC: 150 ml with each other 3. Two largest acceptable FEV1: 150 ml with each other 74 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine STATION 2: INHALER GADGETS INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: At the end of the session, the participants will: 1. Be familiar with the different inhaler gadgets, their uses, advantages and disadvantages. 2. Be able to demonstrate proper use of the different inhaler gadgets. I. Types of inhaler gadgets. 1. Metered dose inhalers a. Pressurized Metered Dose Inhaler (pMDI) i. Rapihaler ii. Ventolin pMDI b. Soft-mist pMDI i. Respimat 2. Dry powder inhalers a. Single unit dose i. Rotahaler ii. Breezhaler b. Multi-dose reservoir i. Turbohaler ii. Nexthaler c. Multi-unit dose i. Diskus ii. Elipta II. Proper inhalation technique for each type of device. • pMDI 1. Shake 4 or 5 times if suspension formulation. 2. Take the cap off. 3. Prime the inhaler. 4. Exhale slowly, as far as comfortable. 5. Hold the inhaler in an upright position. 6. Immediately place the inhaler in the mouth between the teeth, with the tongue flat under the mouthpiece 7. Ensure that the lips have formed a good seal with the mouthpiece 8. Start to inhale slowly, through the mouth and at the same time press the canister to actuate a dose. 9. Maintain a slow and deep inhalation, through the mouth, until the lungs are full of air. This should take an adult 4-5 secs. 10. At the end of the inhalation, take the inhaler out of the mouth and close the lips. 11. Continue to hold breath for as long as possible, or up to 10 sec before breathing out. 12. Breathe normally. 13. If another dose is required, repeat steps 4-12. • 1. 2. 3. DPI Take the cap off (some do not have a cap). Follow the dose preparation instructions in the PIL. Do not point the mouthpiece downwards once a dose has been prepared for inhalation because the dose could fall out. 75 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine 4. Exhale slowly, as far as comfortable (to empty the lungs). Do not exhale into the DPI. 5. Start to inhale forcefully through the mouth from the very beginning. Do not gradually build up the speed of inhalation. 6. Continue inhaling until the lungs are full. 7. At the end of inhalation, take the inhaler out of the mouth and close the lips. Continue to hold breath for as long as possible or up to 10s. III. Controller and Reliever medications. • CONTROLLER MEDICATIONS o ICS/ LABA▪ Salmeterol + Fluticasone • Diskus/ Accuhaler • Metered dose inhaler ▪ Formoterol + Budesonide • Turbuhaler (may also be used as rescue medication) o LABA/LAMA ▪ Umeniclidium + Vilanterol • o Long acting anticholinergic (for COPD) ▪ Tiotropium • Handihaler • Soft-mist inhaler • RESCUE/RELIEVER MEDICATIONS o Short acting B agonists ▪ Salbutamol • Metered dose inhaler • Rotacap • Nebules ▪ Terbutaline • Metered dose inhaler • Turbuhaler o Anticholinergic/ SABA ▪ Salbutamol / ipratropium • Metered dose inhaler 76 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine STATION 3: PEAK FLOW INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: At the end of the session, the students will be able to: 1. Enumerate indications for peak flow monitoring 2. Demonstrate proper technique for doing peak flow 3. Compute for peak flow variability 4. Interpret results of peak flow values PEAK FLOW MONITORING • May help confirm the diagnosis of asthma • 60 L/min (or 20% or more pre-BD PEF) post BD • diurnal variation > 20% (for bid values > 10%) • Improves control of asthma specially in patients with poor perception of symptoms • May help identify environmental (including occupational) causes of asthma symptoms • Advantages: portable, simple to use, may be used at home • Disadvantage: may not correlate directly with FEV1- may underestimate degree of airflow limitation PEAK FLOW VARIABILITY COMPUTATIONS • maximum – minimum divided by mean daily average • minimum am pre-BD divided by recent best- most useful clinically NOTES: 77 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine PEAK FLOW RESULTS 1 PATIENT A – 20-year-old college student complaining of episodes of chest tightness and exertional dyspnea, especially during the “ber” months. She does not smoke, but her boyfriend is a chain smoker. FH is (-) for Asthma but her sister has Allergic Rhinitis. PE is unremarkable. She could not schedule her spirometry as she was in the middle of exam week so was asked to monitor her peak flow for 1 week and bring back the results PEAK FLOW VALUES* AM Pre BD Post BD PM Pre BD Post BD Day 1 300 300 320 340 Day 2 300 310 300 330 Day 3` Day 4 310 320 340 350 300 310 340 350 Day 5 310 310 330 350 Day 6 300 310 340 360 Day 7 310 310 350 360 RESULT AVERAGE * These tests can be repeated during symptoms or in the early morning. Daily diurnal PEF variability is calculated from twice daily PEF as ([day’s highest minus day’s lowest]/mean of day’s highest and lowest) and averaged over a week. Excessive variability in twice-daily PEF over 2 weeks • Adults: average daily diurnal PEF variability > 10% • Children: average daily diurnal variability > 13% Notes: USE COMPUTATION #1 78 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine PEAK FLOW RESULTS 2 PATIENT B – 37-year-old pharmacist, diagnosed to have Asthma 3 years ago. She denies any shortness of breath and says that she hasn’t had any significant Asthma attacks in the past 2 years. She takes Montelukast prn. She consults because she has been having non-productive cough for the past 2 weeks, which wakes her up at night. PE is normal. She was asked to monitor her peak flow for 1 week. PEAK FLOW VALUES personal best = 350 AM PM Pre BD Post BD Pre BD Day 1 250 270 300 Post BD 320 Day 2 260 270 300 330 Day 3` 250 280 310 320 Day 4 290 290 320 330 Day 5 280 290 330 330 Day 6 280 290 320 340 Day 7 270 300 320 340 RESULT AVERAGE Notes: USE COMPUTATION #2 79 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine WORKSHOP 4: LUNG ULTRASOUND INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOME: 1. Identify normal lung ultrasound findings on B mode and M mode 2. Note for movement of the diaphragm on normal respiration 3. Visualize movement of diaphragm on ultrasound on normal, deep inspiration and shallow inspiration Instructions: Students will be grouped by subsection. Their respective facilitators with a faculty lead will help the students during the session, which will last for 30 minutes. There will be 2-3 subsections at a time which will be scanning the standardized patient, taking note of the following: 1. Lung Sliding a. Position of standardized patient/ subject: Supine b. Ultrasound probe: high frequency 12L/ Linear c. Mode: B mode (brightness mode) d. Note for Bat sign e. Note for lung sliding on inspiration and expiration f. Note for a “somewhat” disappearance of this lung sliding when you ask the subject to hold his/her breath g. Note for: • A lines • B lines • Comet tails • Bat sign h. Mode: M mode (motion mode) • Sea-shore sign: normal • Bar code sign/ stratosphere sign: pneumothorax i. Output: An image of the normal sliding of your standardized patient 2. Diaphragm movement on inspiration and expiration a. Position of standardized patient/ subject: Supine b. Ultrasound probe: Low frequency/ curvilinear probe c. Mode: B mode (brightness mode) d. How to scan: Anterior-axillary line on the right; Mid-Posterior axillary line; 5th8th ICS on the left; use spleen or liver as acoustic window and angle probe toward the spine e. Note for diaphragm moving on inspiration- caudad movement of mirror image artifact f. Note for diaphragm moving on expiration- cephalad movement of mirror image artifact g. Note for difference of motion of diaphragm on deep, normal and shallow inspiration. Freeze a good image of each of the three maneuvers. h. Output: Image of the diaphragm during normal, deep and shallow inspiration. 3. Femoral and Popliteal Vein Scanning a. Position the Standardized patient/subject: supine or sitting b. Ultrasound Probe: High Frequency/ Linear probe c. Mode: B Mode (Brightness Mode) d. How to Scan: Femoral Area: With the probe indicator oriented to the right of the patient, on transverse orientation from the inguinal area lightly scan to visualize the Mickey Mouse sign which comprise: the Femoral Artery (appears round in cross section with strong pulsations and non compressible); saphenous vein (compressible) and Femoral vein 80 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine (compressible). Patient should be in a supine position with legs relaxed or internally rotated. Popliteal Area: With the probe indicator oriented to the right of the patient, on transverse orientation from the popliteal crease, lightly scan to visualize the popliteal vein and artery with the popliteal vein which is compressible. Patient may be in a sitting position with legs hanging from the edge of the bed. REFERENCES: Ultrasound Institute, University of South Carolina, USA You may access: Overview of Lung Ultrasound https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WOlz8-km6hE 81 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine TBL 1 ASTHMA: TEAM-BASED LEARNING FOR THIRD YEAR MEDICAL STUDENTS PURPOSE: This team-based learning (TBL) module focuses on the diagnosis and management of patients with asthma in the primary care and ER settings. The students will work as a group in discussing the case. EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES: By the end of this session, learners will be able to: 1. Complete a structured clinical assessment of a patient with symptoms suggestive of asthma, identifying the likelihood of asthma diagnosis. 2. Consider alternate diagnoses for patients presenting with respiratory symptoms. 3. Assess asthma control and asthma severity. 4. Apply stepwise approach to asthma therapy. 5. How to identify patients who are at high risk of a life-threatening asthma attack 6. Manage asthma in the primary care and ER setting. FORMAT: 1. Individual Readiness Assessment Test (iRAT) 2. Team Readiness Assessment Test (tRAT) 3. Discussion of Answers 4. Team Application (Tapp) 5. Discussion of Case Application 6. Post Test REFERENCES: Barnes, P. (2018). Asthma In: Jameson J, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J. eds.Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e (pp. 19571969) New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; http://0-accessmedicine.mhmedical.com.ustlib.ust.edu.ph/content.aspx? bookid=2129&sectioned=159313747. Accessed August28, 2019. 2020 GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. (https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/) 82 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine TBL 2 DYSPNEA (CARDIO-PULMO INTEGRATION): TEAM-BASED LEARNING ON FOR THIRD YEAR MEDICAL STUDENTS PURPOSE: To enhance the ability of third-year medical students to assess the causes of and treatments for common causes of dyspnea OBJECTIVES: 1. To create a differential diagnosis (>1 possible etiology) for causes of dyspnea from common illness scripts representative of typical patients encountered on Internal Medicine services 2. To infer a differential diagnosis to guide initial testing to evaluate for common causes of dyspnea 3. To associate what types of initial therapy are required for the common causes of dyspnea 4. To demonstrate critical thinking skills in coming up with management of the case presented based on physical exam findings, imaging modalities, and laboratory studies. FORMAT: 1. Individual Readiness Assessment Test (iRAT) 2. Team Readiness Assessment Test (tRAT) 3. Discussion of Answers 4. Team Application (Tapp) 5. Discussion of Case Application 6. Post Test ADVANCED PREPARATION: Cardio and Pulmo Module Notes / Workbooks 83 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine ADDITIONAL NOTES: BRONCHIAL ASTHMA Clinical Presentation Asthma is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome affecting the lower respiratory tract. It presents as episodic or persistent symptoms of wheezing, dyspnea, air hunger, and cough. Symptoms may be precipitated or exacerbated by exposure to allergens and irritants, viral upper respiratory tract infections, bacterial sinusitis, exercise, and cold air. Nocturnal symptoms indicate more severe disease, causing awakening in the early morning hours (for those with a normal diurnal schedule). The clinical presentation of asthma is variable with respect to severity, underlying pathogenic mechanisms, effect on quality of life, and responsiveness to treatment. Risk Factors Risk factors for asthma include heredity, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, viral infections in the first 3 years of life, and socioeconomic factors such as income level, the presence of cockroach or rodent infestations in the home, and access to medical care. Heritable factors include genes regulating IgE-related mechanisms, glucocorticoid response, airway smooth muscle development (ADAM33) and components of the immune system (HLA-G).Tobacco smoke is a common exacerbating factor in patients with asthma. Physical Examination Physical findings in stable asthma are nonspecific, and physical examination findings can be normal when the patient is well. Poorly controlled asthma may exhibit auscultatory wheezing or rhonchi, but the intensity of wheezing is a poor indicator of the severity of either airflow obstruction or disease pathology. In an acute exacerbation of asthma, tachypnea, pulsus paradoxus, cyanosis, and use of accessory muscles of respiration may be evident. Differential Diagnosis Upper respiratory tract Vocal cord dysfunction Congestive rhinopathy Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome Lower respiratory tract Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Occupational bronchitis Cystic fibrosis Bronchiectasis Pneumonia Gastrointestinal tract Gastroesophageal reflux disease Cardiovascular system Congestive heart failure Pulmonary hypertension Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease Central nervous system Habitual cough Diagnosis Spirometry is the most important diagnostic procedure for evaluating airway obstruction and its reversibility. It should be performed in all patients in whom asthma is a diagnostic consideration. The maximal volume of air forcibly exhaled from the point of maximal inhalation (forced vital capacity, FVC), the volume of air exhaled during the first second 84 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine of this maneuver (FEV1), and FEV1:FVC ratio are 3 key measures. An FEV1:FVC ratio less than the lower limit of normal (0.7-0.8 in adults, depending on age) indicates airway obstruction. Reversibility of airway obstruction is indicated by an increase in FEV1 of 200 mL or greater and 12% or greater from baseline after inhalation of short-acting β2agonists. Management Please refer to pages 76-85 for relevant algorithms, treatment options and management steps based on the Global Initiative for Asthma. REFERENCES: Global Initiative for Asthma 2019. McCracken JL. Et. al; Diagnosis and management of Asthma in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2017;318(3):279-290 Diagnostic flowchart for diagnosing asthma Reference: 1. 2020 GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/) 2. Philippine Consensus Report on Asthma Diagnosis and management 2019 85 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Table 1 (Australian Asthma Handbook v1.1 Section 1.1 asset ID: 4) Investigating asthma-like symptoms Taking a History Type Recommendation Consensus Consider asthma in adults with (any of): recommendation* • episodic breathlessness • wheezing • chest tightness • cough Consensus Ask about: recommendation* • current symptoms (both daytime and night-time) • pattern of symptoms (e.g. course over day, week or year) • precipitating or aggravating factors (e.g. exercise, viral infections, ingested substances, allergens) • relieving factors (e.g. medicines) • impact on work and lifestyle • home and work environment • smoking history (tobacco, cannabis, exposure to other people’s smoke) • past history of allergies including atopic dermatitis (eczema) or allergic rhinitis (“hay fever”) • family history of asthma and allergies Consensus When respiratory symptoms are not typical, do not rule out the possibility recommendation* of asthma without doing spirometry, because symptoms of asthma vary widely from person to person *Based on clinical experience and expert opinion (informed by evidence, where available) Table 2 (Australian Asthma Handbook v1.1 Section 1.1 asset ID: 4) Findings that increase or decrease the possibility of asthma in adults Asthma is more likely to explain the symptoms if any of these apply Asthma is less likely to explain the symptoms if any of these apply More than one of these symptoms • wheeze • breathlessness • chest tightness • cough Symptoms recurrent or seasonal Symptoms worse at night or seasonal History of allergies (e.g. allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis) Dizziness, light headedness, peripheral tingling Symptoms obviously triggered by exercise, cold air, irritants, medicines (e.g. aspirin or beta-blockers), allergies; viral infections, laughter) Family history of asthma or allergies Symptoms began in childhood Widespread wheeze audible on chest auscultation FEV1 or PEF lower than predicted without other explanation Isolated cough with no other respiratory symptoms Chronic sputum production No abnormalities on physical examination of chest when symptomatic (over several visits) Change in voice Symptoms only present during respiratory tract infections Heavy smoker (now or in past) Cardiovascular disease Normal spirometry or PEF when symptomatic (despite repeated tests) Eosinophilia or raised blood IgE level without other explanation Symptoms rapidly relieved by a SABA bronchodilator Table adapted from: Respiratory Expert group. Therapeutic guidelines Limited. Therapeutic Guidelines: Respiratory Version4. Therapeutic Guidelines Limited. Melbourne, 2009. British Thoracic Society (BTS) Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). British Guidelines on the Management of Asthma. A national clinical guideline. BTS. SIGN. Edinburgh; 2012 86 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Australian Asthma Handbook v1.1 asset ID:2 Table 3 Confirmed variable airflow limitation Documented excessive variability in lung function* (one or more of the tests below) AND documented expiratory flow limitation* Positive bronchodilator (BD) reversibility test* (more likely to be positive if BD medication is withheld before test: SABA ≥4 hours, LABA≥15 hours) Excessive variability in twice-daily PEF over 2 weeks* Significant increase in lung function after 4 weeks of anti-inflammatory treatment Positive exercise challenge test* Positive bronchial challenge test (usually performed only in adults) The greater the variation or the more occasions excess variation is seen, the more confident the diagnosis At a time when FEV1 is reduced, confirm FEV1/FVC is reduced (it is usually >0.75 – 0.80 in adults) Adults: increase in FEV1 of > 12% and > 200 mL from baseline, 10-15 minutes after 200-200 mcg Albuterol (Salbutamol) or equivalent (greater confidence if increase is > 15% and > 400 mL) Children: increase in FEV1 of > 12% predicted Adults: average daily diurnal variability > 10%** Children: average daily diurnal PEF variability > 13%** Adults: increase in FEV1 by 12% and > 200 mL (or PEF by 20%) from baseline and after 4 weeks of treatment, outside respiratory infections Adults: fall in FEV1 of >10% and >200 mL from baseline Children: fall in FEV1 of > 12% predicted or PEF > 15% Fall in FEV1 from baseline of ≥20% with standard dose of methacholine or histamine, or ≥15% with standardized hyperventilation, hypertonic saline or mannitol challenge BD: bronchodilator (short-acting SABA or rapid-acting LABA); FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; LABA: long-acting beta2-agonist; PEF: peak expiratory flow (highest of three readings); SABA: shirt-acting beta2-agonist. * These tests can be repeated during symptoms or in the early morning. Daily diurnal PEF variability is calculated from twice daily PEF as ([day’s highest minus day’s lowest]/mean of day’s highest and lowest) and averaged over a week. For PEF, use the same meter each time as PEF may vary by up to 20% between meters. BD reversibility may be lost during severe exacerbations or viral infections, and airflow limitation may become persistent over time. If bronchodilator reversibility is not present at initial presentation, the next step depends on the availability of other tests and the urgency of the need for treatment. In a situation of clinical urgency, asthma treatment may be commenced and diagnostic testing arranged within the next few weeks, but other conditions that can mimic asthma should be considered and the diagnosis of asthma confirmed as soon as possible. Table 4 GINA assessment of asthma control in adults Asthma symptom control In the past 4 weeks, has the patient had Daytime asthma symptoms more than twice/week? Any night waking due to asthma? SABA reliever for symptoms More than twice a week? Any activity limitation due to asthma? Level of symptom control Uncontrolled WellPartly Controlled Controlled YES NO YES NO YES NO YES NO None of these 1-2 of these 3-4 of these 87 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Risk Factors for Poor Asthma Outcome Assess risk factors at diagnosis and periodically, particularly for patients experiencing exacerbations. Measure FEV1 at start of treatment, after 3–6 months of controller treatment to record the patient’s personal best lung function, then periodically for ongoing risk assessment Having uncontrolled asthma symptoms is an important factor for exacerbations. Additional, potentially modifiable risk factors for flare-ups (exacerbations), even in patients with few symptoms, include: Having any of • High SABA use (with increased mortality if > 1 x 200-dose canister/month) these risk • Inadequate ICS: not prescribed ICS; poor adherence, incorrect inhaler technique factors • Low FEV1, especially if < 60% predicted increases the • Higher bronchodilator reversibility patient’s risk of • Major psychological or socioeconomic problems exacerbations • Exposures: smoking, allergen exposure if sensitized even if they • Comorbidities: obesity, chronic rhinosinusitis, confirmed food allergy have few • Sputum or blood eosinophilia asthma • Elevated FENO (in adults with allergic asthma) symptoms • Pregnancy Other major independent risk factors for flare-ups (exacerbations) • Ever intubated or in intensive care unit for asthma • ≥ severe exacerbations in the last 12 months Risk factors for developing fixed airway obstruction • Preterm birth, low birth weight and greater infant weight gain • Lack of ICS treatment • Exposure tobacco smoke; noxious chemicals; occupational exposures • Low initial FEV1; chronic mucous hypersecretion; sputum or blood eosinophilia Risk factors for medication side-effects • Systemic: frequent OCS; long-term, high dose and/or potent ICS; also taking P450 inhibitors • Local: high-dose or potent ICS; poor inhaler technique FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; OCS: oral corticosteroid; P450 inhibitors: cytochrome P450 inhibitors such as ritonavir, ketoconazole, itraconazole; SABA: short-acting beta2-agonist. Reference: 0. 2020 GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/) 1. Philippine Consensus Report on Asthma Diagnosis and management 2019 88 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Figure 1 Asthma Control Test Score: 25 – Congratulations! You have TOTAL CONTROL of your asthma. You have no symptoms and no asthma-related limitations. See your doctor if this changes. Score: 20 to 24 – On Target Your asthma may be WELL CONTROLLED but not TOTALLY CONTROLLED. Your doctor may be able to help you aim for TOTAL CONTROL. Score: less than 20 – Off Target Your asthma may NOT BE CONTROLLED. Your doctor can recommend an action plan to help improve your asthma control. 89 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Figure 2: Stepwise Management Global Initiative for Asthma Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2020. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/ 90 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Table 5 Initial Asthma Treatment: recommended options in adolescents and adults Presenting symptoms Preferred INITIAL TREATMENT All patients • SABA-only treatment (without ICS) is not recommended Infrequent asthma • As needed low dose ICS-formoterol symptoms, e.g. less than (Evidence B) twice a month Other options include ICS whenever SABA is taken, in combination or separate inhalers * Asthma symptoms or • Low dose ICS with as needed SABA (Evidence need for reliever twice a A), or month or more • As-needed low dose ICS-Formoterol (Evidence A) Other options include LTRA (less effective than ICS, Evidence A), or taking ICS whenever SABA is taken either in combination or separate inhalers (Evidence B). Consider likely adherence with controller if reliever is SABA. ** Troublesome asthma • Low does ICS-LABA as maintenance and reliever # symptoms most days; or therapy with ICS-formoterol (Evidence A) or as waking due to asthma conventional maintenance treatment with asonce a week or more, needed SABA (Evidence A), OR especially if any risk • Medium dose ICS**with as needed SABA factors exist (Evidence A) Initial asthma • Short course of oral corticosteroids AND start presentation is with regular controller treatment with high-dose ICS severely uncontrolled (Evidence A) or # asthma, or with medium-dose ICS-LABA (Evidence D) exacerbation ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; LABS: long-acting beta2-agonist; LTRA: leukotriene receptor antagonist; OCS: oral corticosteroids; SABA: short-acting-beta2-agonist * Corresponds to starting at Step 2 ** Corresponds to starting at Step 3 # Not recommended for initial treatment in children 6-11 years Global Initiative for Asthma Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2020. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/ 91 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Figure 3 SUGGESTED INITIAL CONTROLLER TREATMENT IN ADULTS WITH A DIAGNOSIS OF ASTHMA FIRST ASSESS: Confirmation of diagnosis Symptom control & modifiable risk factors (including ling function) Comorbidities IF : Symptoms most days, waking at night ≥ once a week and low lung function? START WITH: YES Medium dose ICS-LABA (MART or maintenance-only) STEP 4 Low dose ICS-LABA (MART or maintenance-only) STEP 3 Daily low dose ICS or as-needed low dose ICS-Formoterol STEP 2 Daily low dose ICS or as-needed low dose ICS-Formoterol STEP 1 NO Symptoms most days, or waking at nigh ≥ once a week ? YES NO Inhaler technique & adherence Symptoms twice a month or more? Patient preferences & goals YES NO Global Initiative for Asthma Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2020. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/ 92 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine ASSESSMENT OF SEVERITY MANAGEMENT-COMMUNITY SETTINGS The severity of the exacerbation (Figure 4.4-1) determines the treatment administered. Indices of severity, particularly PEF (in patients older than 5 years), pulse rate, respiratory rate, and pulse oximetry, should be monitored during treatment. Most patients with severe asthma exacerbations should be treated in an acute care facility (such as a hospital emergency department) where monitoring, including objective measurement of airflow obstruction, oxygen saturation, and cardiac function, is possible. Milder exacerbations, defined by a reduction in peak flow of less than 20%, nocturnal awakening, and increased use of Table 6 Severity of Asthma Exacerbations* Breathless Talks in Alertness Respiratory rate Accessory muscles and suprasternal retractions Wheeze Pulse/min. Pulsusparadoxus PEF after initial bronchodilator % predicted or % personal best PaO2 (on air)┼ and/or PaCO2 ┼ Mild Moderate Severe Walking Talking Infant – softer shorter cry; difficulty feeding At rest Infant stops feeding Can lie down Prefers sitting Sentence Phrases May be agitated Usually agitated Increased Increased Normal rates of breathing in awake children: Age < 2 months 2-12 months 1-5 years 6-8 years Usually not Usually Hunched forward Words Usually agitated Often >30/min Normal Rate < 60/min < 50/min < 40/min < 30/min Usually Moderate , often only Loud end expiratory < 100 100-120 Guide to limits of normal pulse rate in children: Infants 2-12 months-Normal Rate Preschool 1-2 years School age 2-8 years Absent May be present < 10mm Hg 10-25 mm Hg Over 80% Approx. 60-80% Normal Test not usually necessary > 60 mm Hg < 45 mm Hg < 45 mm Hg Respiratory arrest imminet Drowsy or confused Usually loud Paradoxical thoracoabdominal movement Absence of wheeze > 120 Bradycardia < 160/min < 120/min < 110/min Often present > 25 mm Hg (adult) 20-40 mm Hg (child) < 60% predicted or personal best (< 100 l/min adults) or response lasts < 2hrs < 60 mm Hg Absence suggests respiratory muscle fatigue Possible cyanosis > 45 mm Hg; Possible respiratory failure (see text) SnO2%(on air)┼ > 95% 91-95% < 90% Hypercapnea (hypoventilation) develops more readily in young children than in adults and adolescents. *Note: The presence of several parameters, but not necessarily all, indicates the general classification of the exacerbation. ┼Note: Kilopascals are also used internationally; conversion would be appropriate in this regard. 93 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Figure 4 Management of Asthma Exacerbations in Acute Care Setting Initial Assessment (see Figure 4.1-1) • History , physical examination (auscultation, use of accessory muscles, heart rate, respiratory rate, PEF or FEV1, oxygen saturation, arterial gas if patient in extremis) Initial Treatment • Oxygen to achieve O2 saturation ≥ 90% (95% in children) • Inhaled rapid-acting β2-agonist continuously for one hour. • Systemic glucocorticosteroids if no immediate response, or if patient recently took oral glucocosteroid, or if episode is severe. • Sedation is contraindicated in the treatment of an exacerbation. Reassess after 1 hour Physical examination, PEF, O2 saturation and other tests as needed. Criteria for Moderate Episode: • PEF 60-80% predicted/personal best • Physical exam: moderate symptoms, accessory muscle use Treatment: • Oxygen • Inhaled β2-agonist and inhaled anticholinergic every 60min • Oral glucocorticosteroids • Continue treatment for 1-3 hours, provided there is improvement Criteria for Severe Episode: • History of risk factors for near fatal asthma • PEF< 60%;predicted/personal best • Physical exam: severe symptoms at rest, chest retraction • No improvement after initial treatment Treatment: • Oxygen • Inhaled β2-agonist and inhaled anticholinergic • Systemic glucocorticosteroids • Intravenous magnesium Reassess after 1-2 Hours Good Response within 1-2 Hours: • Response sustained 60 min after last treatment • Physical exam normal: No distress • PEF > 70% • O2 saturation > 90% (95% children) Incomplete Response within 1-2 Hours: • Risk factors for near fatal asthma • Physical exam: mild to moderate signs • PEF < 60% • O2 saturation not improving Poor Response within 1-2 Hours: • Risk factors for near fatal asthma • Physical exam: symptoms severe, drowsiness, confusion • PEF < 30% • PCO2> 45 mm Hg • PO2< 60 mm Hg Admit to Acute Care Setting • Oxygen • Inhaled β2-agonist ± anticholinergic • Systemic glucocorticosteroid • Intravenous magnesium • Monitor PEF, O2 saturation, pulse Admit to Intensive Care • Oxygen • Inhaled β2-agonist + anticholinergic • Intravenous glucocorticosteroids • Consider intravenous β2-agonist • Consider intravenous theophylline • Possible intubation and mechanical ventilation Reassess at intervals Improved: Criteria for Discharge Home • PEF > 60% predicted/personal best • Sustained on oral/inhaled medication Home Treatment: • Continue inhaled β2-agonist • Consider, in most cases, oral glucocorticosteroids • Consider adding a combination inhaler • Patient education: Take medicine correctly Review action plan Close medical follow-up Poor Response (see above): • Admit to Intensive Care Incomplete response in 6-12 Hours (see above): • Consider admission to Intensive Care if no improvement within 6-12 hours Improved (see opposite) 94 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Figure 5 Global Initiative for Asthma Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2020. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/ 95 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine PULMONARY ARTERIAL HYPERTENSION (PAH) / PULMONARY HYPERTENSION (PH) Intended Learning Outcomes: • Recognize the signs and symptoms of pulmonary hypertension • Define diagnostic modalities applicable to the clinical presentation of a patient suspected to have pulmonary hypertension • Interpret test results for the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. • Know possible treatment regimen depending on the diagnosis and severity of pulmonary hypertension. Definition: • Pulmonary Hypertension (PH): a hemodynamic and pathophysiological condition defined as mean PAP >25 mmHg at rest assessed by RHC • Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH): a clinical condition characterized by presence of pre-cap PH in the absence of other causes of pre-cap PH • In recent journals (ERJ), AmPAP of 20 mmHg should be considered as the upper limit of normal value. This new definition has been recently proposed by other. However, this abnormal elevation of mPAP in isolation is not sufficient to define PVD as it can be due to an increase in CO or PAWP. • Pre-capillary PH is best defined by the concomitant presence of mPAP>20 mmHg, PAWP ≤15 mmHg and PVR ≥3 WU emphasizing the need for RHC with mandatory measurement of CO and accurate measurement of PAWP Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension (PH) 1 PAH 1.1 Idiopathic PAH 1.2 Heritable PAH 1.3 Drug- and toxin-induced PAH (table 3) 1.4 PAH associated with: 1.4.1 Connective tissue disease 1.4.2 HIV infection 1.4.3 Portal hypertension 1.4.4 Congenital heart disease 1.4.5 Schistosomiasis 1.5 PAH long-term responders to calcium channel blockers (table 4) 1.6 PAH with overt features of venous/capillaries (PVOD/PCH) involvement (table 5) 96 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine 1.7 Persistent PH of the newborn syndrome 2 PH due to left heart disease 2.1 PH due to heart failure with preserved LVEF 2.2 PH due to heart failure with reduced LVEF 2.3 Valvular heart disease 2.4 Congenital/acquired cardiovascular conditions leading to post-capillary PH 3 PH due to lung diseases and/or hypoxia 3.1 Obstructive lung disease 3.2 Restrictive lung disease 3.3 Other lung disease with mixed restrictive/obstructive pattern 3.4 Hypoxia without lung disease 3.5 Developmental lung disorders 4 PH due to pulmonary artery obstructions (table 6) 4.1 Chronic thromboembolic PH 4.2 Other pulmonary artery obstructions 5 PH with unclear and/or multifactorial mechanisms (table 7) 5.1 Haematological disorders 5.2 Systemic and metabolic disorders 5.3 Others 5.4 Complex congenital heart disease PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; PVOD: pulmonary veno-occlusive disease; PCH: pulmonary capillary haemangiomatosis; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction. Pulmonary Hypertension Symptoms: - Breathlessness - Fatigue - Weakness - Chest pain/angina - Syncope/presyncope - Abdominal distention 97 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine - Raynaud’s in about 10% (worse prognosis) Hemoptysis (rare) Pulmonary Hypertension Physical Signs: - Left parasternal lift /RV heave - Loud P2 of 2nd Heart sound - Pansystolic murmur of Tricuspid regurgitation - Diastolic murmur of Pulmonary insufficiency - Right-sided 3rd heart sound Pulmonary Hypertension Physical Signs (Advanced State): - Jugular vein distention - Hepatomegaly - Peripheral edema - Ascites - Cool extremities Clues for Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension: - clear lungs (Normal breath sounds) - no clubbing(except in CHD, PVOD) - central and peripheral cyanosis - hoarseness (Ortner syndrome) - stigmata of secondary causes of PAH: o scleroderma, cirrhosis, HIV, OSA ACCF/AHA Diagnostic Approach to PAH 2 98 University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery Department of Medicine Section of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine Four stage approach to diagnosis (Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009) • • • • Clinical suspicion of PAH o symptoms, known risk factors Exclusion of Group 2 (left heart disease) and Group 3 (lung disease) PH o ECG, chest radiograph, echocardiography, PFTs, HRCT Exclusion of Group 4 (CTEPH) PH o ventilation/perfusion lung scan PAH evaluation and characterisation o CT pulmonary angiography, CMRI, haematology, biochemistry, serology, and ultrasonography o functional class and exercise capacity o right heart catheterisation (RHC) Treatment of PAH Stage A Stage B Stage C Stage C Stage D High risk with no symptoms PAH with + VDC PAH with - VDC PAH with - VDC Low Risk High Risk Refractory symptoms requiring special intervention Hospice Transplantation Inotropes, atrial septostomy Consider multidisciplinary team Combination therapy IV meds (Flolan or Trepostonil) Aldactone and digoxin Dietary sodium restriction, diuretics Bosentan +/- Sildenafil +/- Ventavis Calcium Channel Blockers Risk factor reduction, patient and family education Sleep apnea, Obesity, Uncontrolled hypertension and/or depress LVEF, drug abuse REFERENCES: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 20th Edition; Chapter 304 ESC/ERS Guidelines 2009 Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension.Gérald Simonneau, David Montani, David S. Celermajer, Christopher P. Denton, Michael A. Gatzoulis, Michael Krowka, Paul G. Williams, Rogerio Souza European Respiratory Journal 2019 53: 1801913; DOI: 10.1183/13993003.01913-2018 99