Ecocritical analysis and Ao-Naga myths present in Temsula Ao’s Poems

advertisement

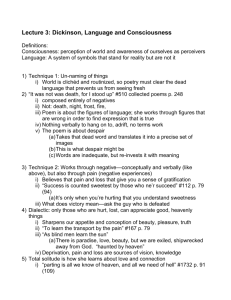

Shraman Paul M.A in English Literature West Bengal State University Ecocritical analysis and Ao-Naga myths present in Temsula Ao’s Poems Ecocriticism, as an academic discipline, primarily explores the relationship between literature and the physical environment, extending its scope from nature writing and canonical literature to various forms of media such as film, television, theatre, and architectural discourse. At its core, Ecocriticism, according to Cheryll Glotfelty, aims to bring back professional authenticity for the "undervalued genre of nature writing.” (Wikipedia). Ecocriticism, which has its roots in William Ruckert's 1978 article "Literature and Ecology: An Experiment in Ecocriticism" seeks to improve ecological literacy in literary works by analysing how humans interact with the natural world. In "Contemporary Literary and Cultural Theory" (2013), Pramod K. Nayar defines ecocriticism as a critical approach that is in line with ecological activism and examines how nature is portrayed in cultural works: “It aligns itself with ecological activism and social theory with the assumption that the rhetoric of cultural texts reflects and informs material practices towards the environment, while seeking to increase awareness about it and linking itself (and literary texts) with other ecological sciences and approaches” (2013: 242). (P.K Nayar) Ecocriticism traces its origins to early 20th-century American literature, influenced by transcendentalists like Emerson, Fuller, and Thoreau. In England, it roots in the 1790s British Romanticists, notably Wordsworth, who emphasized on the man-nature relationship in his poetry. When it comes to talk about ecocriticism, Raymond Williams' "The Country and The City" (1985) becomes very important. It delves into nature, countryside, and city in 18thcentury English literature, contributing to the development of ecocritical thought. In the realm of Indian English writing, particularly from the North East, ecocriticism emerges prominently. Poets like Mamang Dai and Temsula Ao champion the ecological richness of their surroundings, advocating preservation against environmental threats. Their poetry, marked by a distinctive presence of nature, portrays it not only as a backdrop but as a spiritual force in artistic creation. The poets underscore that harm to nature jeopardizes the identity of the people, intricately linked to the natural world. North East Indian English poetry, encapsulated by Mamang Dai and Temsula Ao, resonates with a profound ecological consciousness, urging the safeguarding of the region's ecology, culture, and identity. (Aonok Grace) Temsula Ao: Temsula Ao's poem “Stone People from Lungterok” draws on the myths and folklore of the Ao Naga community to present an ecocritical perspective on the relationship between nature and human origins. The poem explores the idea that the Ao ancestors emerged directly from the earth, positioning them as intrinsically connected to the land. The poem opens by introducing "Lungterok" as the mythical birthplace of the "stone people," immediately evoking a sense of earthiness and geological emergence. According to the Aos their first forefathers emerged out of the earth at the place called Lungterok. These were three men and three women (Dancing Earth). The vivid image of the stone people being: born Out of the womb Of the earth Powerfully depicts nature as a maternal, life-giving force. Through this organic imagery, Ao rejects notions of human supremacy over nature, instead advocating for an ecocentric worldview that sees humanity as emerging from and dependent on the natural world. Throughout the poem, Ao uses rich descriptive language to characterize the stone people as possessing profound ecological wisdom passed down through oral traditions. They are knowledgeable In birds’ language And animal discourse Suggesting an innate communicative bond between human, avian, and mammalian species. Their status as The worshippers Of unknown, unseen Spirits Of trees and forests, Of stones and rivers further cements their harmonious relationship with the environment. The stone people hold a deep reverence for the natural world that modern societies have lost. Ao also examines the duality of the stone people as both "gentle lovers and savage heroes," grappling with the complexities of humanity's ties to nature. While positioned as wise ecologists, they also engage in bloodthirsty practices like headhunting. The poet does not shy away from these contradictions, boldly confronting the nuances of human-nature relations. Ultimately, Ao advocates for embracing ancestral ecological knowledge to develop greater environmental ethics. She closes with uncertainty about whether the stone people's wisdom persists, asking "or are the stone-people yet to come of age?" This final question prompts self-reflection on how modern societies might cultivate more sustainable relationships with the natural world, learning from mythic eco-traditions. Through rich symbolism and evocative language, Ao's poem provides an ecocritical perspective on human origins and humanity's complex bond with nature. She champions an ecocentric worldview that foregrounds the interdependency of people and environment, challenging human-cantered ideologies. Blending oral mythology and metaphor, Ao calls for honouring ancestral ecological practices while continuing to evolve more harmonious ways of inhabiting the earth. The poet gives voice to the "stone people" and the land itself, advocating for environmental ethics through mythopoeic imagination. Temsula Ao's poem "Soul Bird" on the other hand draws on the animist beliefs of her Naga ancestors to present a vision of the human soul merging with the natural world after death by taking of a bird, insect or sometimes even a caterpillar. The poem provides an ecocritical perspective by depicting the continuity between human life and the environment through the metaphor of the soul becoming a bird (Dr Narasingaram Jayashree). The poem opens with the line "They are chanting prayers" immediately establishing the context of a recent death of a loved one. In the next lines, Ao writes: They are chanting prayers But I watch a lonely hawk Soaring Amidst the swirling blue. Here Ao puts forth the Naga folk belief that the departed soul takes the form of a bird, in this case a hawk. The soul is not detached from the earth but remains, "Amidst the swirling blue." There is a direct transition of the human spirit into an animal form, emphasizing the soul's immersion in nature. The poem continues with the hawk flying high and appearing moving in hesitant circles Emitting an earthly sound, Hawk-eyes seemingly riveted On the mould below, Fences in By newly-cut bamboo This peaceful unification of the soul, earth, and sky represents the oneness between humanity and the natural environment. The soul's journey does not remove it from nature but integrates it more fully. Meanwhile, the grandmother of the poet is found addressing, See that keening bird in the sky? That’s your mother’s soul Saying her final goodbye, to the poet. As the poem further progresses, the myth present in Ao-Naga religion gets another confirmation and the readers get to know about the death the poet’s mother. The visual imagery depicts the soul bird being wholly subsumed into the vast expanse of sky. The repetition of "I watched a lonely hawk" underscores the speaker bearing witness to the soul completing its transition in the cycle of life and death. The soul does not depart to some immaterial realm, but finds its place of rest in the blue sky, which hints at transcendence through merging with nature's essence. Ao's poem provides an alternative to beliefs that position humanity as disconnected from the environment. Her ecocritical perspective emphasizes that in life and death we remain integral parts of the natural world. The cyclical movement of the soul into an animal form represents that interconnection. Through lyrical verse and organic imagery, Ao advocates for an ecological awareness that overcomes notions of human exceptionalism over nature. Ultimately it can be said, Temsula Ao's poems "Stone People From Lungterok" and "Soul Bird" offer profound ecocritical perspectives rooted in Naga mythology. Ao challenges anthropocentric views by portraying the stone people's emergence from the earth and the soul's seamless integration with nature after death. Through vivid imagery and mythopoeic imagination, she advocates for a harmonious relationship between humanity and the environment, urging a return to ancestral ecological wisdom. Ao's poetry becomes a call for environmental ethics, embracing the continuity between life and nature. In doing so, she contributes to the broader discourse of ecocriticism, underscoring the importance of recognizing our interconnectedness with the natural world for a sustainable future. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Bibliography: [1] Aonok, Grace; “Recovering Lost Lore Through Poetry: An Examination of Select Poems by Temsula Ao”; October 2022; 2022 IJCRT | Volume 10, Issue 10, ISSN 2320-2882; Page550-555 [2] Jayashree, Narasingaram; “Ecocentric and Mythopoeic Facets in Temsula Ao’s Poem, Stone People from Lungterok”; 4th and 5th Aug, 2017; IJTRD ISSN: 2394-9333; Page- 343-45. [3]Wikipedia [4] Nongkynrih, KS; Singh Ngangom, Robin; "Dancing Earth Anthology" ; 6 November 2009; Paperback; Page- 1-5 [5] Nayar, Pramod K; “Contemporary Literary and Cultural Theory: From Structuralism to Ecocriticism.” 1 January 2009; Paperback; Page- 242.