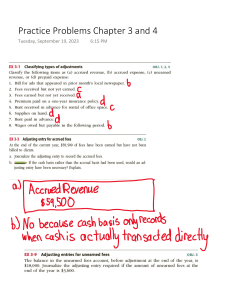

For the exclusive use of J. Ruesche, 2023. 9-810-041 REV: FEBRUARY 10, 2014 JOSEPH B. LASSITER III WILLIAM A. SAHLMAN NOAM WASSERMAN Nantucket Nectars: The Exit Well, we knew we were in an interesting position. We had five companies express interest in acquiring a portion of the company. Sometimes you have to laugh about how things occur. Tropicana (Seagram) and Ocean Spray became interested in us after reading an article in Brandweek magazine that erroneously reported that Triarc was in negotiations to buy us. (See Exhibit 1 for a copy of this article.) At the time, we hadn’t even met with Triarc, although we knew their senior people from industry conferences. We have no idea how this rumor began. Within weeks Triarc and Pepsi contacted us. We told no one about these on-going negotiations and held all the meetings away from our offices so that no Nectars employee would become concerned. It was quite a frenetic time. The most memorable day was just a few days ago actually. Firsty and I were in an extended meeting with Ocean Spray, making us late for our second round meeting with Pepsi. Ultimately, Tom and I split up: Firsty stayed with Ocean Spray and I met with Pepsi. Ocean Spray never knew about the Pepsi meeting. Tom and I have learned under fire throughout our Nectars experience, but this experience was a new one for us. — Tom Scott, co-founder of Nantucket Nectars It was certainly exciting to have some companies interested in acquiring Nantucket Nectars. But, should the founders sell at this time? The company was doing great, better than they had ever imagined. See Exhibit 2 for historical financials. Should they continue negotiating with potential buyers to find out the market value of their company? Ultimately, they needed to decide whether to sell the company. Background Tom Scott and Tom First met in freshman year while students at Brown University. The following summer, the two joined four others and launched a painting venture on Cape Cod for the summer season. Tom Scott recalled that “we were all friends; Tom and I were no closer than any others in the group.” Yet, he noticed that “Tom First and I saw business similarly”: We enjoyed similar things—trying new tools, making the flyers, learning how to work together, etc.—and we liked studying business and ”playing business“ the same way kids ”play fort.” Within the group there were fights and disagreements and people assuming the ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Professors Joseph B. Lassiter III and William A. Sahlman and Research Associate Jon M. Biotti prepared the original version of this case, “Nantucket Nectars,” HBS No. 898-171. This version was prepared by Professors Joseph B. Lassiter III, William A. Sahlman, and Noam Wasserman. HBS cases are developed solely as the basis for class discussion. Cases are not intended to serve as endorsements, sources of primary data, or illustrations of effective or ineffective management. Copyright © 2009, 2014 President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, call 1-800-5457685, write Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, MA 02163, or go to www.hbsp.harvard.edu/educators. This publication may not be digitized, photocopied, or otherwise reproduced, posted, or transmitted, without the permission of Harvard Business School. This document is authorized for use only by Joseph Ruesche in Founder's Dilemmas Fall 2023 taught by CHRISTINA LUBINSKI, Copenhagen Business School from Oct 2023 to Mar 2024. For the exclusive use of J. Ruesche, 2023. 810-041 Nantucket Nectars: The Exit role of ”boss” over others. Tom and I used to laugh about it and marvel at the human element. We just wanted it to work and, interestingly, neither Tom nor I ever tried to be boss. We liked the whole more than our individual roles. We always worked hard and wanted the customers to be happy. Always. Despite their jerkiness, their unfairness. Even at the cost of profit sometimes. The following summer when Tom Scott created Allserve, a floating convenience store serving boats in the Nantucket Harbor, “I asked three of my former paint teammates to join me. Tom was an obvious ask, but I asked two others as well. Soon, though, the two others showed signs of laziness, selfishness, or it wasn’t ‘cool enough’ for them. Whereas Tom and I clicked and saw the world the same.” After graduation Tom and Tom decided to return to Nantucket to continue their Allserve business, as Tom Scott explained: “After four years working off-and-on together, what was once a team of six became a team of two; it was a process of elimination or attrition.” At the time, they sold ice, beer, soda, cigarettes and newspapers and performed services such as pumping waste and delivering groceries and laundry for boats in the Harbor. The founders did not even sell juice at that time. As First recalled, “We started what was basically a floating 7-Eleven.”1 During the winter of 1990, First recreated a peach fruit juice drink that he had discovered during a trip to Spain. The drink inspired the two founders to start a side-business of making fresh juices. In the spring of 1990, the founders decided to hand-bottle their new creation and sell them off their Allserve boat. “We started by making it in blenders and selling it in cups off the boat. But we also put it in milk cartons and wine bottles—basically anything that we could find.”2 Customers loved the product, prompting the founders to open the Allserve General Store on Nantucket’s Straight Wharf. Soon thereafter, other Nantucket stores started carrying the product. In its first year, Nantucket Allserve sold 8,000 cases of its renamed juice, Nantucket Nectars, and 20,000 the following year. Financing and Marketing In the first two years, the two founders invested their collective life savings, about $17,000, in the company to contract an outside bottler and finance inventory. For the next two years, Nantucket Nectars operated in an undercapitalized state on a small bank loan. Tom Scott recalled the situation: We were scraping along. Everything was going back into the company. By early 1993, our few employees hadn’t been paid in a year, never mind that Tom and I hadn’t paid ourselves in three and a half years. But we worked all sorts of odd jobs on the side, especially during the winter. It was especially tough because we could see the juice really taking off. Ultimately, the two founders persuaded Mike Egan, the founder and former CEO of Alamo Car Rentals, to invest $600,000 in Nantucket Nectars in exchange for 50% of the company. (Egan maintained 93% of Alamo’s stock.) The founders originally met Egan while serving his boat in Nantucket Harbor during the early days of Allserve. While the founders were concerned about ceding a controlling share to an outsider, they needed the money and had no other options. Egan performed the function of trusted advisor while not meddling in the day-to-day operations of the business. As Egan explained, “I really made the investment because it makes me wake up in the morning and feel like I’m twenty-five again, trying to grow another company.” 1 Beverage Aisle, February 1996. 2 Beverage Aisle, February 1996. 2 This document is authorized for use only by Joseph Ruesche in Founder's Dilemmas Fall 2023 taught by CHRISTINA LUBINSKI, Copenhagen Business School from Oct 2023 to Mar 2024. For the exclusive use of J. Ruesche, 2023. Nantucket Nectars: The Exit 810-041 The founders used the capital to improve distribution and increase inventory. First, they secured better, independent bottlers. Secondly, the founders created a unique private distribution strategy where they themselves sold, delivered, and stocked the product. An early employee explained: We were doing it all. We leased some warehouse space, bought an old van, and went up and down the street selling Nantucket Nectars and our passion to make the brand succeed. The retailers immediately loved our story and enjoyed seeing us stock the shelves ourselves. Becoming our own distributor allowed us to control the positioning of the product. We often rearranged the shelves to ensure that Nantucket Nectars was better positioned than Snapple. In order to speed up their growth, the founders obtained the exclusive rights to distribute Arizona Iced Tea in Massachusetts. The founders wanted to piggyback off the strong brand and higher volumes of Arizona Iced Tea to build their own distribution arm and to get more outlets for their own products in the market. Within three months the distribution division grew from seven to one hundred employees and from 2,000 to 30,000 cases sold per month. At the same time, the founders repackaged and reformulated their own product while convincing small stores to carry Nantucket Nectars alongside the red-hot Arizona Iced Tea. By the end of 1994, revenues surpassed $8 million. Nantucket Nectars relied on creative packaging, rapid and original product introductions, wordof-mouth and a memorable story line. With the increased capital raised from Egan, the founders segued into radio ads as a means to push the Nantucket “story.” The founders described early mishaps in radio ads and placed messages underneath their bottle caps in order to attract consumer interest. (See Exhibit 3.) For example, an early radio ad described how employee Ned Desmond, on the first sales trip to Boston, crashed the Nantucket Nectars van, destroying all the juice. Another radio ad explained how early employee Larry Perez accidentally dropped the proceeds from the first sale into the harbor. Growth The early days were extremely frustrating for the two founders. While customers clearly liked the product, Nantucket Nectars only had three flavors—Cranberry Grapefruit, Lemonade, and Peach Orange—and the founders were completely unsure of how to grow the business. Tom Scott explained: “The frustrations that we dealt with were immense. We didn’t know what point-of-sale was, we didn’t know what promotion was, we didn’t know what margin we should be making.”3 As a means to differentiate, Nantucket Nectars committed to creating high quality, all natural juice beverages without regard for the margins; the quality of the product came first. This strategy translated into replacing high fructose corn syrup with only pure cane sugar, and to using four times the juice of other major brands to improve on their mantra of quality and taste. The founders also differentiated their product by introducing a proprietary 17.5 ounce bottle to complement their existing 12 ounce line as compared to competitors’ standard 16 ounce bottle. From the original three juice flavors, Nantucket Nectars developed 27 flavors across three product lines during the first three years: 100% fruit juices, juice cocktails and ice teas/lemonades. The new distribution business allowed the founders to penetrate more of the small outlets and to begin building up a presence in larger stores and chains. Unfortunately, they also learned that the economics of the distribution business really required one of the "big brands" or you just could not 3 Beverage Aisle, February 1996. 3 This document is authorized for use only by Joseph Ruesche in Founder's Dilemmas Fall 2023 taught by CHRISTINA LUBINSKI, Copenhagen Business School from Oct 2023 to Mar 2024. For the exclusive use of J. Ruesche, 2023. 810-041 Nantucket Nectars: The Exit carry the overhead. In 1995, the founders sold their distribution arm after losing $2 million in the previous year. The founders concentrated on marketing their own product and developing the Nantucket Nectars brand name. The priority at Nantucket Nectars was “moving the juice.” The company switched the distribution of Nantucket Nectars to a combination of in-house salesforce and outside distributors. With the direct salesforce, Nantucket Nectars called the store accounts to sell the product. The salesforce also employed the strategy of visiting all small retailers to make sure that the product was displayed well, “eye to thigh,” and also to check the distributor’s work. The strategy was to build steadily a sustainable organization through strong relations with either the best distributors or individual vendors. As Tom Scott explained, “we were not trying to build a house of cards, we wanted solid long-term growth.” Nantucket Nectars was fortunate to have caught a new wave emerging in the beverage industry, the “New Age” segment, including ready-to-drink teas (a three-year CAGR of 24% during 19921995), water (34% CAGR), juices (32% CAGR) and sports drinks (12% CAGR). Driving this strong growth were trendy young consumers pursuing healthier lifestyles yet faced with fast-paced lifestyles and shortened lunches. They appreciated large, single-serve packaging of New Age beverages and the “gulpability” of lighter, non-carbonated, natural fruit juices. Customers had no switching costs. Some people questioned the sustainability of any New Age beverage brand given the “fad” status of this segment. Competition surfaced in three major ways in the New Age beverage world. First, a competitor might simply undercut in pricing to flood the market while also offering a high quality or innovative product. The second way of competing involved image and brand strength: brand advertising, packaging, trade and consumer promotions. Lastly, brands competed, especially the large players in the beverage industry, by blocking the smaller, less powerful players from the retailer shelf space. So far, more than 100 companies from traditional beverage companies like Coca Cola to regional startups like Arizona launched New Age beverages hoping to capture shifting consumer tastes. Product innovation was a critical element of competitiveness and created an incredibly fierce battle for shelf space, especially among regional companies focused on differentiating themselves through flavors, packaging and image. Many industry analysts believed that competition would increase as New Age beverages became the latest battle ground in the Cola Wars. Coke, Pepsi and Seagrams were all fighting to become the best “total beverage company” to serve the masses while also responding to new beverage trends. New Age beverages were an opportunity to bolster flattening cola and alcohol businesses with shortterm profits, and to improve their competencies at serving niche markets. These firms supported a portfolio of beverage brands with expensive marketing and sophisticated distribution skills. Their access to supermarkets through controlling shelf space, vending machines, convenience stores and fountain distribution channels combined with mass marketing and brand awareness provided them with distinct advantages in developing brands even though their procedures and image inhibit their ability to exploit non-traditional, rapidly changing market opportunities. Furthermore, scale lowered a beverage company’s cost structure by decreasing the cost of per unit ingredients and distribution. Profitability and Cost Management Fiscal year 1995 represented the first year of profitability for the company. The company’s margins were among the lowest in the New Age beverage category given the founders’ emphasis on quality. Unfortunately, high sales growth forced the founders to focus on increasing production to 4 This document is authorized for use only by Joseph Ruesche in Founder's Dilemmas Fall 2023 taught by CHRISTINA LUBINSKI, Copenhagen Business School from Oct 2023 to Mar 2024. For the exclusive use of J. Ruesche, 2023. Nantucket Nectars: The Exit 810-041 meet high demand, rather than delivering quality at a favorable cost. Their lower margins were also a result of limited futures contracts in commodity procurement. The company’s rapid growth and emphasis on quality ingredients accentuated its competitive disadvantages in raw material procurement and plant scheduling. Because of difficulty in predicting growth, the founders were unable to institutionalize future contracts on ingredients. As a consequence, the company was heavily dependent on the harvests as competitors were more likely to secure products if there were a shortage. For example, due to the poor 1995 cranberry harvest, Nantucket Nectars got no cranberries because Ocean Spray controlled all the supplies. This competitive disadvantage in procurement had an even greater impact on Nantucket Nectar’s margins because of the higher fruit content in their products. Nantucket Nectars’ Strategy In August 1997, responding to the launch of competitors’ new product lines, Nantucket Nectars launched a new line of beverages, called Super Nectars, which were herbally enhanced and pasteurized fruit juices and teas. Four of the six new flavors were made from no less than 80% real fruit juice while the remaining two were naturally steeped from green tea and flavored with real fruit juice and honey. Each Super Nectar was created with a concern for both great taste and good health. The line of Super Nectars included Chi’I Green Tea, Protein Smoothie, Vital-C, Ginkgo Mango, Green Angel, and Red Guarana Tea. There was evidence to suggest that Nantucket Nectars should maintain their growth for at least the next five years (see Exhibit 4) and that the company could have tremendous upside in the supermarket channel, where 55% of all New Age beverages were sold but which only accounted for 1% of Nantucket Nectars’ sales (see Exhibit 5). Further upside might come from geographic expansion; only 9% of the company’s sales came from each of the Midwest and West regions of the United States. The founders were also aware that their success to date was accomplished through the more fragmented channels like convenience stores, delis, educational institutions and health and gourmet stores which demanded single-serve product. They also wanted to market their product through the supermarket channel which demanded multi-serve product. Nantucket Nectars had rolled out a larger-sized bottle (36 ounce bottle) for the supermarkets but the company was having difficulty securing shelf space in the larger supermarket chains. The Snapple deal. Outside of macro-economic conditions and the stock market jitters of October 1997, the Snapple deal profoundly affected the New Age beverage market. In November, 1994, Quaker Oats had purchased Snapple from Thomas Lee for $1.7 billion. By 1997, Quaker Oats conceded its defeat, selling Snapple to Triarc for $300 million, while firing their chief executive officer, William Smithburg. Industry experts blamed Snapple’s decline on Quaker’s problems with Snapple’s distributors as well as a new marketing strategy. Quaker Oats replaced Howard Stern and “Wendy the Snapple Lady” with the corporate “Threedom is Freedom” advertising campaign. Quaker Oats also attempted to take away the most profitable distribution business from the distributors in order to utilize its own Gatorade distribution arm. The distributors relegated Snapple to secondary status, causing Snapple sales to decline precipitously. Quaker’s strategy to drop their old distribution network became known as Snappleization within the distribution industry: a distributor lost its distribution contract after a beverage company was acquired by a bigger player. The acquirer moved distribution either in-house or simply to larger distributors after the first distribution network helped build the market for the beverage. 5 This document is authorized for use only by Joseph Ruesche in Founder's Dilemmas Fall 2023 taught by CHRISTINA LUBINSKI, Copenhagen Business School from Oct 2023 to Mar 2024. For the exclusive use of J. Ruesche, 2023. 810-041 Nantucket Nectars: The Exit Sell? The founders wondered what to do with the company. If they decided to proceed with a sale, they wondered how to handle the negotiations in order to maximize the price. See Exhibit 6 for descriptions of major potential bidders. Tom Scott and Tom First wondered how to structure the potential transaction. They both believed strongly in the upside potential of their company but were also concerned about holding the stock of a different company. Should they negotiate the best cash deal possible without a long-term management responsibility or should they negotiate for acquirer stock in order to participate in the company’s continued upside? How would the chosen strategy affect the valued employees who had helped build the company? The founders wondered what significant assets and skills within Nantucket Nectars drove their corporate value and therefore deserved a premium for the brand. The founders came up with the following list: A more appealing story than any other juice beverage company (great material for a company with a large marketing budget and more distribution power) A stabilizing cost structure Access to 18-34 market Last good access to single-serve distribution in the New Age beverage market Best vehicle for juice companies to expand into juice cocktail category without risking their own brand equity As Tom First described the situation, “The difficult question is how do we figure out what the value of Nantucket Nectars is to someone else, not just us.” The founders believed that most acquirers would provide scale economies on costs of goods sold decreasing costs approximately 10% to 20% depending on the acquirer. Exhibit 7 shows enterprise-value analyses under both standalone (i.e., remain independent) and strategic-sale scenarios, using various multiples and discount rates. The founders were also very concerned with the outcome after a sale. Nantucket Nectars currently has 100 employees of which there were 15 accountants, 20 marketers, 57 salespeople, 5 sales administrators and 3 quality control people. Depending on the structure of the potential transaction, what would happen to these people? Another major concern was that the culture of the firm would change drastically depending on whether a transaction was consummated and with whom. Nantucket Nectars still maintained a nonformal dress code; it was very uncommon to see anyone dressed in business attire. The organization of the firm was still non-hierarchical with all employees able to approach the two Toms. Tom First described this concern: “Destroying the entrepreneurial spirit that has made the company special is one of my biggest fears. Once you start departmentalizing, you lose that. It is essential that we maintain our culture so that work is still fun.” The founders were also concerned about the management involvement of any potential strategic partner. Both founders wanted to continue to run the company if possible. Lastly, the founders did not want to have their sales and marketing story negatively affected because of ownership issues. Would consumers continue to enjoy the Nantucket Nectars story if the company were actually owned by a large public company? 6 This document is authorized for use only by Joseph Ruesche in Founder's Dilemmas Fall 2023 taught by CHRISTINA LUBINSKI, Copenhagen Business School from Oct 2023 to Mar 2024. For the exclusive use of J. Ruesche, 2023. Nantucket Nectars: The Exit Exhibit 1 810-041 Brandweek Article on Potential Transaction Source: Karen Benezra, Brandweek, Vol. 38 Issue 29, (July 21, 1997), p. 29. Exhibit 2 Historical Financials of Nantucket Nectars ($000s) December 31 of each year 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 Total Revenue $233 $379 $978 $8,345 $15,335 $29,493 Cost of Sales 172 317 765 6,831 11,024 20,511 61 62 213 1,514 4,311 8,982 Marketing and Advertising 0 0 0 320 875 2,581 General and Administrative 82 62 90 3,290 3,344 5,432 Total Expenses 82 62 90 3,610 4,219 8,013 -21 0 123 -2,096 91 969 0 4 0 104 137 247 -21 -4 123 -2,199 -45 722 0 5 7 53 139 301 -21 -9 116 -2,252 -184 421 0 0 0 0 16 52 -21 -9 116 -2,252 -200 369 Gross Profit EBITDA Amortization and Depreciation EBIT Interest Expense Earnings before Taxes Income Tax Expense Net Income (Loss) Source: Company documents. 7 This document is authorized for use only by Joseph Ruesche in Founder's Dilemmas Fall 2023 taught by CHRISTINA LUBINSKI, Copenhagen Business School from Oct 2023 to Mar 2024. For the exclusive use of J. Ruesche, 2023. 810-041 Exhibit 3 Nantucket Nectars: The Exit Nantucket Nectars Typical Bottle Cap Source: Company materials. Exhibit 4 Projected U.S. Retail Sales of New Age Beverages, 1991 to 2000 (in millions) Category 1991 Alternative Fruit Drinks Gourmet/Natural Sodas Flavor-essenced Waters Juice Sparklers Total 1995 2000 CAGR (1991-2000) $236.8 371.9 304.1 232.9 $857.0 627.7 329.7 238.4 $1,328.8 697.5 259.2 231.2 21.1% 7.2 (1.8) (0.1) $1,145.7 $2,052.8 $2,516.7 9.1% Source: Beverage Industry, March 1997, p. 51. Exhibit 5 Locations of New Age Beverage Sales, All versus Nantucket Nectars Location of All New Age Beverages Sold, 1996 Location Supermarkets Convenience Stores and/or Smaller Mass-Volume Stores Others Total Percentage Sold: All Companies 55% 35% 10% Percentage Sales: Nantucket Nectars 1% 6% 93% 100% 100% Source: Beverage Industry, March 1997, p. 50. 8 This document is authorized for use only by Joseph Ruesche in Founder's Dilemmas Fall 2023 taught by CHRISTINA LUBINSKI, Copenhagen Business School from Oct 2023 to Mar 2024. For the exclusive use of J. Ruesche, 2023. Nantucket Nectars: The Exit Exhibit 6 810-041 List of Potential Buyers and Strategic Match Potential Bidder Strategic Match Ocean Spray The founders knew the Ocean Spray senior management from industry conferences and believed that there was a good match of culture. Ocean Spray was private which would allow Nantucket Nectars to operate in a similar fashion: less disclosure, less hassle, and less short-term pressure to hit earnings. The founders also knew that Ocean Spray generated a good internal cash flow which could be used to fund Nantucket Nectar growth. They also knew that Nantucket Nectars might be able to exploit Ocean Spray’s loss of Pepsi distribution which might cause them to bid aggressively. Ocean Spray is the world’s largest purchaser of non-orange fruit juice, especially berries, tropicals and other exotics. Lastly, Ocean Spray maintained a network of five captive bottling plants plus several long term arrangements with bottlers giving secure, national manufacturing coverage at advantageous cost and quality control. The founders were worried by the loss of Pepsi distribution. Industry experts believed that the distribution agreement would terminate in May, 1998 with 50% of current singleserve distribution handled by Pepsi-owned bottlers (approx. $100MM) with another $100MM handled by Pepsi franchisees. Thus, Ocean Spray could lose as much as $200 million in sales (from a base of $1.05 billion) if they could not find a good distributor or could not distribute effectively themselves. Ocean Spray, however, maintained strong power on the grocery shelves, especially in the Northeast. Pepsi Pepsi seems more prepared to take risks with new products in the New Age segment. Pepsi recently terminated its distribution arrangement with Ocean Spray which will take effect sometime in early 1998. Many industry insiders believe that Pepsi entered into this distribution arrangement to learn as much as possible about single serve New Age beverages before entering the market themselves. Skip Carpenter, a Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette equity analyst, described the action as a “move that clearly signals a bold new way in which PepsiCo will compete in the juice segment going forward.” In late 1996, Pepsi launched a cold, ready-to-drink sparkling coffee drink with Starbucks coffee called Mazagran. In 1995, Pepsi also launched Aquafina, a bottled water drink. One major concern for the founders was that Pepsi has a history of downscaling the quality of products, such as Lipton Brisk Tea, in order to achieve higher volume. Triarc (Snapple and Mistic) The founders believed that Triarc provided the best platform to grow the Nantucket Nectars business the most over the next two years. Through ownership of Snapple, RC Cola and Mistic, Triarc has immediate access to a national single-serve network to push the Nantucket Nectar product. One concern was that Triarc would want to replace many of Nantucket Nectar’s distributors because of redundancy. While the written contracts with the distributors were favorable concerning termination without too much cost, Nantucket Nectars worried about reprise from distributors (similar to what happened to Quaker Oats after they bought Snapple, which created the term “Snappleization”). Source: Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette Beverage Industry Report; Skip Carpenter; July 14, 1997; DLJ Research report, July 14, 1997. 9 This document is authorized for use only by Joseph Ruesche in Founder's Dilemmas Fall 2023 taught by CHRISTINA LUBINSKI, Copenhagen Business School from Oct 2023 to Mar 2024. For the exclusive use of J. Ruesche, 2023. 810-041 Nantucket Nectars: The Exit Exhibit 7 Analysis of Current Enterprise Value, Standalone vs. Strategic Sale (valuations in $000s) Standalone: Assumptions Company remains independent and achieves financial targets for 1997-1998. 1999-2002 revenues grow at 20-25%. Gross margins remain at 34.3% through 2002. Operating margins and working capital items consistent with 1998 levels. Capital expenditures grow in line with sales (no significant capital expenditures assumed in model) Assumes value is capitalized (exit) year-end 2002. EBITDA (exit multiples) Discount rate 9.0 10.0 11.0 12% $47,235 $52,434 $57,634 14% $42,320 $46,995 $51,671 16% $37,974 $42,186 $46,398 18% $34,123 $37,924 $41,726 Strategic Sale: Assumptions Company consummates sales of majority interest to strategic buyer at end of 1998. Through integration with strategic buyer… o 1999-2002 revenues grow at 25-30%. o Gross margins improve from 34.3% in 1997 to 37.3% in 2002. o Operating margins improve to 13% by 2002. Working Capital items consistent with 1998 levels. Capital expenditures grow in line with sales (no significant capital expenditures assumed in model) Assumes value is capitalized (exit) year-end 2002. EBITDA (exit multiples) Discount rate 9.0 10.0 11.0 12% $145,259 $159,934 $175,609 14% $130,644 $143,841 $157,037 16% $117,707 $129,596 $141,485 18% $106,231 $116,961 $127,690 Source: Company documents. 10 This document is authorized for use only by Joseph Ruesche in Founder's Dilemmas Fall 2023 taught by CHRISTINA LUBINSKI, Copenhagen Business School from Oct 2023 to Mar 2024.