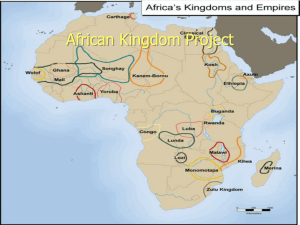

THE TRANS-SAHARAN TRADE 1.0 Nature 1.1: This was the traffic flow between North Africa and West Africa through the Sahara Desert. 1.2: In practical terms, it involved trade contacts between North Africans and the populations of the Sudanese states, who in turn related with their counterparts in the forest zone. 1.3: The trans-Saharan trade existed well before the birth of Christ, but it received an added fillip from about the first century AD with the camel (“ship of the desert”) as the principal transport animal. 1.4: Until about the eighth century, the control of the trans-Saharan trade was in the hands of the desert Berbers. But the initiative was taken over by the Muslim population of the North African states following the establishment of Islam there from the eighth century. 2.0 Routes 2.1: The trans-Saharan trade was carried on along a complex network of routes. However, our area's routes may be broadly grouped into three branches. 2.2: Westerly branch: Linked Morocco with the region of the Senegal River and the upper reaches of the Niger River. 2.3: Central branch: Linked Algeria with the commercial centres on the middle reaches of the Niger. 2.4: Easterly branch: Linked Tunisia and Tripoli with Hausaland and Kanem-Borno in the Lake Chad area. 3.0 Commodities 3.1: The commodities traded can be divided into two categories. First, there were state necessities such as gold and slaves sent north; and salt, horses and weapons, which went south. 3.2: The other category of items were luxury goods, and they included expensive cloth, pepper, ivory, kola nuts, and leather goods. 3.3: Gold was obtained from the forest belt. There were four major goldfields: Bambuhu (Bambuk) in the regions of the Upper Senegal (Eastern Senegal/Western Mali); Bure in the Upper Niger (Guinea); Lobi in the Upper Volta (southwestern Burkina Faso); and the Akan forests (modern Ghana) south of the Volta River. 3.4: Salt was mined in the Sahara regions, where there were large deposits of hard rock salt. These were quarried for export. The major salt-producing centres were Teghazza (Northern Mali), Taodeni (northern Mali), Idjil (Central Mauritania) and Bilma (Northeast Niger). 4.0 Significance 4.1: The trans-Saharan trade was important in the rise and growth of the Sudanese states. 4.2: In their heyday, the cities of Kumbi Saleh, Jenne, Timbuktu, and Gao emerged as the emporia for the import and export trade. 4.3: In the Central Sudan, Kanem-Borno and the Hausa states emerged as important termini of the trans-Saharan trade. 4.4: The trans-Saharan trade was an important medium in the diffusion of North African cultural influence, especially Islam, in the Sudanese states. GHANA 1.0 Growth 1.1: The Soninke constituted the principal group in the empire of Ghana. At the height of its power in the eleventh century, the empire extended over parts of the present-day Republics of Senegal, Mauritania, and Mali. 1.2: Little is known concerning the earliest period of the history of Ghana. Available evidence suggests that Ghana was already founded by the end of the fourth century. 1.3: By the eighth century, when Arab traders first visited Ghana, it had emerged as a powerful state in the Western Sudan. In the next two centuries, Ghana developed into a vibrant empire. 1.4: The development of Ghana into a powerful empire is most closely associated with its progressive involvement in the trans-Saharan trade. 2. 0 Administration 2.1: The king of Ghana was highly revered by his subjects. People could only approach the king by prostrating full-length with their heads covered in dust. No one could sneeze in the presence of the king. Only the king and his crown prince wore sewn clothing, others draped unstitched wears. On his demise, the king was buried with his attendants and a sizeable portion of his property in the belief that he would continue to live a royal life in the world beyond. 2.2: He publicly dispensed justice and assisted in administration by a Council of Ministers. At the height of Ghana’s power in the eleventh century, the king’s government had come to include also Muslim Arab traders who acted as interpreters, scribes, and treasurers. 2.3: For provincial administration, the local rulers and those of the vassal states ruled their subjects. To secure and guarantee the loyalty of vassal rulers, they were required to send their sons to the king’s court as hostages. The king also exacted tributes from his vassal rulers. 2.4: For the defence of the state and imperial expansion, the king of Ghana could muster a considerable number of warriors. 3.0 The Almoravids 3.1: The ascendant position of Ghana in the Western Sudan was marked by its conquest and seizure of the commercial town of Awdaghust (Southern Mauritania) in 992, which it wrested from the Sanhaja Berbers. 3.2: Ghana’s troubles started with the formation of the Almoravids, a militant Muslim movement that arose from among the Sanhaja Berbers of Western Sahara composed of three main branches: Lamtuna, Juddala, Mussufa. The Sanhaja had converted to Islam since the first half of the eighth century. 3.3: In 1039, the leader of the Juddala tribe called Yahya ibn Ibrahim arrived from a pilgrimage to Mecca with a Berber Islamic preacher named Abdullah ibn Yasin. The Juddala leader had returned with the preacher to enhance the quality of Islamic practice among his people. 3.4: Ibn Yasin’s views were considered too puritanical, and so when in 1041ibn Ibrahim died, the Juddala expelled ibn Yasin from their society. 3.5: Ibn Yasin withdrew into seclusion but succeeded in drawing along with him a sizeable body of followers from among the Lamtuna. In 1042, he came out of his hideout with a resolve to prosecute a Jihad among the Sahanja tribes. His followers were called al-murabitun, corrupted in European languages as Almoravids. By 1053, he had succeeded through force and persuasion in winning all the Sanhaja sub-groups to his movement. 3.6: In 1054, the Almoravids moved against and captured Sijilmasa (in Morocco). Sijilmasa, a northern terminus of the trans-Saharan trade routes, was controlled by the expanding Zenata Berbers, who were the enemies of the Sahanja. In the same year (1054), the Almoravids regained Awdaghust from Ghana 3.7: Ibn Yasin was killed in battle in 1059 and was succeeded by Abu Bakr ibn Umar as the head of the Almoravids. The Almoravids engaged Ghana in several skirmishes until they conquered it in 1076 and forced many citizens to adopt Islam. Abu Bakr died in 1087, and thereafter the Almoravid movement collapsed in the Western Sudan. His supporters held on to the conquest in Morocco, from where they took Spain also till 1147. 4.0 The Decline of Ghana 4.1: Ghana immediately regained its independence, but irreparable damage had been done to its power and prestige. 4.2: The years under Almoravid rule had weakened Ghana’s links with the people she had controlled, and her authority over them was lost in some of the former provinces. Some people split off and became separate kingdoms. Among those who established a new and separate kingdom were the Soso, a Soninke subgroup. 4.3: Ghana was finally eclipsed when in 1203, Sumanguru Kante of the Soso inflicted a crushing defeat on Ghana. 4.4: Sumanguru’s ascendancy was cut short by the emergent state of Mali, which by 1240 had established control over the territories of the Soso and Ghana. THE MALI EMPIRE 1.0 Establishment 1.1 The empire of Mali rose from among the Mandinka, who refer to their territory as Manding. They are also popularly known as the Malinke, while Mali is used for the name of their territory. 1.2 The Malinke had been organised into several chiefdoms by the beginning of the thirteenth century. Kangaba was the most dominant of the chiefdoms. 1.3 In 1224, Sumanguru Kante of the Soso Kingdom brought the Malinke under his political sway. 1.4 In about 1230, a Kangaba prince called Sundiata returned from exile and succeeded in uniting all the Malinke chiefdoms under his leadership. At the head of this united force, he defeated Sumanguru in 1235 at the Battle of Kirina. 1.5 Sundiata thereafter established his authority over the Soso territory and began building a new state from among the Malinke. The city of Niani was established as the capital. 2.0 Growth 2.1 By 1255, when he died, Sundiata had already laid the foundations for transforming his new state into an empire. 2.2 Sundiata was succeeded by his son Mansa Ulli (1255-70), during whose reign Mali experienced further expansion. Important commercial centres such as Walata, Timbuktu, and Gao were incorporated into the empire. 2.3 However, the momentum was halted under the reigns of the next three rulers in the period between 1270 and 1285. 2.4 In 1285, a high official of the state called Sakura usurped the throne. By the time he died in 1300, Sakura had relaunched Mail on the path of greatness. 3.0 Zenith 3.1 It was during Mansa Musa's reign (1312-37), Mali attained the peak of its power and prosperity. 3.2 He maintained an administrative machinery designed to ensure good governance. 3.3 Trade and commerce expanded as the various trade routes and centres were made safe by the security agents of the state. 3.4 The power of Mali under Mansa Musa was complemented by promoting Islam and links with the Muslim world. In 1324 Mansa Musa embarked on a pilgrimage to Mecca via Egypt. 3.5 He created such an impression of prosperity in the course of the pilgrimage that Mali was to appear on two world maps prepared by Europeans later in the fourteenth century. 3.6 Mansa Musa was succeeded by his son Muhammad who reigned for four years. Suleyman, a brother to Mansa Musa, ruled afterwards. The power of Mali was maintained under the reign of Suleyman (1341–1360). 4.0 Decline 4.1 Between Suleyman’s death in 1360 and 1400, there were as many as six rulers. The period was characterised mainly by dynastic wrangling and coups d'état. 4.2 The deterioration continued during the fifteen century. In about 1420, the ruler of the rising state of Songhai carried war into Niani; simultaneously, Mali’s control over Timbuktu was threatened by attacks from the Mossi in the south and the Tuaregs in the north. The Tuaregs eventually captured the town as well as Walata in 1434. 4.3 From then until about the seventeenth century, when it finally ceased to exist, the Mali Empire gradually shrank to its original Malinke territories from which it had developed into imperial status. THE SONGHAI EMPIRE 1.0 Growth 1.1 The Songhai comprised the Sorko (fishermen), the Gow (hunters), and Do (farmers). The Sorko were the dominant element. 1.2 The Songhai state had been established as early as the seventh century under a line of kings titled Dya, with a capital at kukiya. But by the tenth century, the capital had been shifted to Gao, which was becoming an important commercial centre. 1.3 The presence of Muslim traders also resulted in the conversion of the Dya ruling dynasty to Islam in about 1019. 1.4 The Songhai State was incorporated into the Mali Empire during the mid-thirteenth century. But Songhai regained its independence in 1275, under Ali Kolon, who established a new dynasty titled Sunni. 1.5 The independence won by Songhai was short-lived for the energetic Sakura, who usurped the Mali throne in 1285 again brought Songhai under Mali control. 1.6 Mali rule over Songhai was eventually terminated in the last quarter of the fourteenth century as the power of Mali declined. 2.0 Sunni Ali 2.1 Under the reign of Sunni Ali (1464-92), Songhai was transformed into an imperial state. 2.2 Sunni Ali was a soldier-king. He possessed a seasoned and well-organised army of infantry and cavalry wings. He also had a naval fleet 2.3 He attacked and conquered the two commercial centres of Timbuktu (1469) and Jenne (1473). 2.4 In the south, Sunni Ali led several expeditions against the Dongo, the Mossi, the Kebbawa, and the Borgawa. His most outstanding achievement in this direction was in 1483 when he inflicted a crushing defeat on the Mossi, thus ending intermittent Mossi invasions into the Niger valley and the Songhai area since the mid-thirteenth century. 2.5 At the time of his accidental death, Sunni Ali was the master of a great empire based on the Niger. The empire extended from Dendi [on the Nigeria/Niger border] in the east to the frontiers of the gradually shrinking Mali in the west. The Kanuri State of Kanem-Borno 1.0 Geographical Coverage 1.1 The history of the Kanem-Borno Empire may broadly be divided into two phases. The first phase covered the period from c. ninth to the fourteenth century when the seat of government was at Njimi in Kanem, east of Lake Chad, while the second phase lasted between the fifteenth to the early nineteenth century when the capital was located at Ngazargamu in Borno, west of Lake Chad. 1.2 Altogether, the boundaries of the empire at various times extended over parts of the modern Republics of Niger, Chad, Cameroun, and a large section of present Yobe and Borno States in Nigeria. 1.3 The dominant and ruling group in the Kanem-Borno Empire were the Kanuri, and this is why the empire is often referred to as the Kanuri Empire and the two periods mentioned above as the first and second Kanuri Empires, respectively. 2.0 Growth and Expansion 2.1 The Kanuri were before the end of the first millennium AD speakers of related language groups who had evolved one or two petty states by the ninth century. However, from the mid-ninth century, they all gradually came to be consolidated into a single kingdom and people. The king was addressed by the title of Mai. 2.2 The state was from the last quarter of the eleventh century ruled by a dynasty called Saifawa. The founder of this dynasty was Hume (c. 1075–1086). Hume traced his descent from Saif ibn Dhu Yazan, a Yemeni-Arab hero of the sixth century, and it is for this reason, the dynasty is referred to as the Saifawa. 2.3 By the twelfth century, the Saifawa had established a unified kingdom in Kanem (east of Lake Chad), with its seat of government at Njimi. Imperial expansion commenced from the reign of Hume’s successor, Dunama (c. 1086–1140). He is said to have had a force of 100,000 mounted soldiers and 120,000 foot soldiers. 2.4 Dunama was followed by a string of successors, especially in the thirteenth century, committed to far-flung imperial expansions to secure the state's commercial benefits. In this connection, available sources lay particular stress on the imperial activities of Dunama Dibalami (c. 1210– 1248), who at most times led his military expeditions in person. He secured control over Fezzan on the trans-Saharan trade route and Traghan, a place well over 800 miles from Njimi, establishing a governor there for commercial considerations. 2.5 Dunama Dibalami was also noted for his Islamic zeal. As a Muslim reformer, he destroyed a sacred object called Mune, which was believed to contain the guardian spirit of the state; and as a patron of learning, he built a hostel in Cairo for Kanem people. 3.0 Political Decline 3.1 But the thirteen century marked the apogee of Kanuri history in Kanem. The turn of the fourteenth century saw a Kanuri state on the brink of collapse. This was because the opening years of the century were of civil wars. These were compounded by external problems. Thus, military engagements with the So, who inhabited the southern and western sides of Lake Chad, resulted in the death of four Mais in succession, all before 1325. East of Kanem were the Bulala, whose incursion into Saifawa land became progressively devastating. Indeed, the Bulala wars filled most of the second half of the fourteenth century such that in the 1360s and the 1370s, five Mais fell on the battlefield fighting the Bulala. Unable to bear the situation any longer, Mai Umar Ibn Idris (1382–87) gave up Kanem and sought refuge in the country of Borno, west of Lake Chad. For all practical purposes, the evacuation from Kanem by the Saifawa marked the end of what is often being referred to as the First Kanuri Empire. 3.2 But even though the Saifawa moved westwards, their troubles were yet to be over. Not only were they continually subjected to incessant Bulala attacks–which resulted in the death of two more Mais just before the end of the fourteenth century–but the fifteenth century opened with the fragmentation of the Saifawa royal lineage into two branches. The result, of course, was rivalry for the throne, disregard of proper succession procedures and the successful contention of pretenders to the throne. Also, the political instability denied the Saifawa of permanent capital in their new homeland. For the better part of the first half of the fifteenth century, capitals were continually shifted with the installation of new Mais. 4.0 Revival 4.1 The Saifawa drift into political abyss was halted with the accession to the throne of Ali Ghaji (1465–1497). Indeed, he has often been described as the founder of the Second Kanuri Empire, which was to endure till the early periods of the nineteenth century. 4.2 Of the many measures taken by Ali Ghaji in the revival of Kanuri power, three were of particular importance. Ali Ghaji’s first concern was building a new capital since there had been no permanent capital since the evacuation from Njimi. A new capital was built at Ngazargamu, which, sited as it was west of Lake Chad, was far from the enemies of the Kanuri (the So in the south and Bulala in the east) and well placed for future extension into the eastern parts of Hausaland. 4.3 To maintain the internal security thus gained and defend the kingdom against external attacks, Ali Ghaji raised the strength of the royal army. His major campaigns were directed against the Bulala, and his successes in these battles broke Bulala power. He thus bequeathed to his successors a military legacy that saw Kanuri power at its heights in the next two centuries. 4.4 But perhaps the most important achievement of his reign was the elimination of the segmentation of the ruling dynasty and enabling the circumstances for succession by his direct descendant. Thus, he was succeeded by his son, Idris Katakarmabe (1497–1515), and grandson, Muhammad (1515–38), respectively. The re-introduction of the system of direct succession (primogeniture) forestalled dynastic wrangling, which had been a source of political instability in the Kanuri state in the past two centuries. THE HAUSA STATES 1.0 Geographical Coverage and Origin Traditions 1.1 The Hausa are predominantly located in northern Nigeria in the present-day Sokoto, Zamfara, Kebbi, Kaduna, Katsina, Kano and Jigawa States. They also inhabit parts of the Niger Republic, while Hausa-speaking colonies are to be found in the northern parts of the Republics of Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, Benin, and as far as the western sections of the Republic of Sudan. 1.2 Bayajidda /Daura Legend: The Hausa were administered in a number of states, which developed between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries. According to tradition, these states were established through the agency of a legendary figure called Bayajidda. The development of the Hausa states is attributed to the offspring of this figure. The Bayajidda, or Daura legend as it is called, relates that at an unspecified date in remote times, Bayajidda fled from Baghdad, his home country, to Kanem. He was, however, subsequently to flee again from Kanem in fear of the Mai. He travelled westwards to Daura in Hausaland, whose people were deprived of water from a well by a sacred snake. Bayajidda killed the snake, and in gratitude and admiration, the queen of Duara married him. The marriage produced a son called Bawo, whose six sons became founders of dynasties that established six Hausa states. Thus, Gazaura founded a dynasty in Daura; Kumaiyu in Katsina; Bagauda in Kano; Zamagari in Rano; Gunguma in Zazzau; Duma in Gobir. Another dynasty was established in Garun-ta-Gabas by Biram, a son of Bayajidda, through an earlier marriage with the daughter of the Mai of Kanem. These states then became known as the Hausa Bakwai (i.e., the Hausa [pure] seven); as district from another set of seven states known as the Banza Bakwai (the bastard seven) said to have been founded by dynasties established by Bayajidda’s grandchildren through concubines. The Banza Bakwai are: Zamfara, Kebbi, Gwari, Yawuri, Nupe, Kwararafa (Jukun), and Oyo. 1.3 Although historians generally agree that the Bayajidda legend need not be regarded as authentic history, there is still no consensus on its interpretation. A recent interpretation is that the element of marriage in the story suggests that the early states were forged on marriage alliances. The aspect concerning the Banza Bakwai is probably an attempt to underscore the historical links between the Hausa and their more important neighbours. 2.0 Rise of States 2.1 By the beginning of the fourteenth century, some of the Hausa states had begun to experience political and economic expansion due to increasing involvement in the trans-Saharan trade. In terms of political administration, each state was governed by a king addressed as Sarki and chosen from among members of the ruling lineage. 2.2 By the end of the fourteenth century, Kano had emerged as the most prominent Hausa state. A period of territorial conquest began under the reign of Sarkin Kananeji (1390–1410). He is said to have spent most of his reign on the battlefield. Evidence of the involvement of his kingdom in the trans-Saharan trade is shown in the fact that he employed new military equipment such as padded horse armour, iron helmets, and coats of chain mail. Muhammad Rumfa (1463–99) had an even more successful career. To his reign is attributed several administrative innovations. Other highlights of his reign included: (a) the extension of the Kano city walls and the building of new gates, (b) the establishment of the Kurmi market, the main market in Kano; (c) the adoption of royal symbols to include horses, drums, flags, Ostrich-feather fans, and the long copper horns [Kakaaki] 2.3 Two other notable Hausa states during our period were Katsina and Zazzau. Both states achieved remarkable political and economic growth under the reigns of Muhammad Korau (1445– 93) and Muhammad Rabo (last quarter of the fifteenth century), respectively. Indeed, the two rulers are traditionally regarded as the first Muslim kings of their respective states. 3.0 External Influences 3.1 Hausaland also experienced external influences in varied forms. During the fifteenth century, some of the Hausa states were brought under the political sway of Kanem-Borno. In the process, Kanuri cultural elements were introduced into Hausaland. For example, the Hausa states adopted such Kanuri titles as galadima, chiroma, and kaigama. 3.2 Other external influences included the settlement of foreign immigrants. The most notable were the Fulani, both herdsmen and Muslim clerics. Foreign immigration and involvement in the trans-Saharan trade led to the introduction of Islam. The religion is said to have been introduced into Hausaland first in Kano. Its introduction is attributed to the Wangarawa (Malinke traders) during the reign of Yaji (1349–85). Although royal patronage was initially insignificant, the increasing commercial prosperity of Kano drew many Muslim clerics to the city. Islam received a boost under Rumfa. He built mosques and strove to introduce Islamic concepts in administration. For guidance, he entered into correspondence with a celebrated North African scholar, al-Maghili, in 1491/2, who in response visited Kano, and wrote a small treatise on the art of government for his use. The essay was titled “The Obligation of Princes.” In demonstrating his commitment to the Islamic faith, Rumfa cut down the traditional sacred tree in Kano and erected a mosque on the site. He also instituted the public celebration of the festivities at the end of the Ramadan fast, the Eid el-Fitr. 3.3 A similar process of Islamisation was taking place in Katsina during this period. The Wangarawa are said to have introduced Islam into Katsina under Korau. Korau built a mosque modelled on those of Gao and Jenne. Like Rumfa, he was visited by al-Maghili, who urged the application in Katsina of the ideas set out in his treatise. The two immediate successors of Korau who assumed office in the last years of the fifteenth century also supported the promotion of Islam. Ibrahim Sura (1493–98) is remembered as a conscientious devotee who forced his subjects to pray and imprisoned those who refused. After him came Ali (1498–1524), whose steadfastness earned him the nickname Murabit, i.e., religious warrior. ISLAM IN THE SUDANESE STATES 1.0 Advent 1.1 Islam came to Sudanese West Africa through North African traders from the eighth century. For the greater part of the period before 1500, the religion was associated more with the courts (palaces) of the various states and their ruling classes. 1.2 And even then, there was a lot of syncretistic combination of Islamic and traditional practices in court ceremonials and observances. Outside the ranks of the ruling classes, Islam was embraced by traders who were in close contact with the foreigners from North Africa. 2.0 Impact 2.1 With Islam came literacy and Islamic education. The city of Timbuktu, for example, became from the heyday of the Mali Empire, the foremost centre of Islamic learning in Sudan. 2.2 New ideas on administration were also introduced. Islamic scholars were appointed as advisers of Sudanese rulers. 2.3 They acted as interpreters, scribes, and treasurers to most of the rulers of the states in the Sudan. 3.0 Western Sudan 3.1 In the empire of Mali, the cause of Islam was most advanced by Mansa Musa (1312–37) and his brother Mansa Suleyman (1341–1360). 3.2 Suleyman built mosques and instituted the Friday public prayers. He attracted Muslim scholars to his country and was himself a student of religious sciences, which comprised theology, law, and Arabic grammar, among other disciplines. 3.3 Under Mansa Musa and Suleyman, Muslim scholars had a privileged status and much influence. The mosque, the chief Imam’s house, and a few designated areas in the empire were regarded as sanctuaries for wrongdoers. 4.0 Central Sudan 4.1 In Kano, Islam received a boost under Muhammad Rumfa (1463–99). He ordered the building of mosques and instituted the observance of festival prayers. He also ordered the cutting down of the sacred tree of Kano and built a mosque on the site. In so doing, he demonstrated a clear and official break with the non-Islamic past. 4.2 A similar action to what Rumfa did in Kano had earlier been done in Kanem-Borno during the thirteenth century when Mai Dunama Dibalami (c. 1210–1248) ordered that the mune, a sacred object traditionally considered to be significant for the peace of the state, should be cut open. This action represented an important symbolical break at the state level with local religious cults. 5.0 Overview 5.1 Traditional values and ideas on religion and politics were still well-entrenched. Hence, even though such empire builders like Sundiata and Sunni Ali had Islamic backgrounds, they drew their support from the traditional cults at critical points in the development of their states. 5.2 Nevertheless, the factor of Islam in governance could not be ignored. The factor of Islam was significant in the overthrow of Sunni Baru, Sunni Ali’s successor, by Mohammed Ture. Under Muhammad Ture, Islam made its greatest impact in Songhai. THE BENIN KINGDOM 1.0 Early Phase 1.1 The Benin kingdom, as symbolized by its monarchy, was established on shaky foundations. The first three kings or oba of the kingdom are said to have been confronted with formidable obstacles during their reigns. 1.2 Their authority and power were particularly undermined by a hereditary order of chiefs called Uzama n’Ihinron. The Uzama chiefs were the kingmakers. 1.2 The king ranked no more than a primus inter pares (first among equals) in the administration of the kingdom. 2.0 Growth: Ewedo 2.1 But this state of affairs was halted when Ewedo, the fourth oba, assumed office. Ewedo compelled all chiefs to stand in his presence; formerly, the Uzama remained seated. He also disallowed them from using swords of state or conferring titles. 2.2 Ewedo built a new palace and instituted a hierarchy of chiefs to serve the palace, whose loyalty would strictly be to the oba. 2.3 Servants of the oba belonged to one of the three palace associations. The most senior association was called Iwebo, which took charge of the oba’s wardrobe, including his regalia. The second was Iweguae, which comprised the ruler’s attendants and domestic servants. The third association, called Ibiwe, was responsible for duties concerning the needs of the oba’s wives and children. 2.4 Ewedo also laid the foundation for Benin expansion by conquest. 3.0 Consolidation: Ewuare 3.1 Ewuare instituted a hierarchy of town chiefs similar in structure to that, which already existed in the palace. His council of state thus comprised palace chiefs—i.e., the heads of the palace associations—and town chiefs. 3.2 Royal authority was further consolidated by Ewuare’s institution of a chieftaincy title, the Edaiken, which was to be assumed by the prince designated as the heir apparent (the crown prince). This measure had the effect of reducing further the influence of the hereditary Uzama chiefs who hitherto were the kingmakers. 3.3 The religious and sacred aspects of kingship were strengthened. He introduced the annual Igue festival, which was designed to demonstrate the oba’s mystical powers. 3.4 Benin became a formidable military power and grew into an empire. 3.5 The tempo of Benin military expansion was accelerated under Ozolua, Ewuare’s youngest son, who acceded to the throne in c. 1481. He is reported to have been killed by his troops because of his lust for war. EARLY PORTUGUESE CONTACTS 1.0 Aims and Objectives 1.1 The advent of the Portuguese may be explained by a number of reasons, all of which derived from the principal aim of establishing an alternative sea route to India. 1.2 the Portuguese intended to undermine the power of the Islamic states of North Africa by establishing footholds in West Africa. Related to this point was the desire to convert the people of West Africa into Christianity and to attempt to establish contact with a legendary Christian king called Prester John, who would assist the Portuguese in their project. 1.3 There was the desire to satisfy European curiosity and inquisitiveness by widening the little European knowledge of the African continent. 1.4 The third and most important point was the Portuguese desire to gain access to the sources of the West African gold trade, the knowledge of which filtered to Europe through North Africa. 2.0 Activity 2.1 The most important centre of Portuguese activity was the coastline of modern Ghana, which they called Costa da Mina ([Gold] Mine Coast) because they were able to establish a gold trade with the local communities.* 2.2 Another area of Portuguese activity on the West African coast was the region between modern Sierra Leone and Liberia, which they called the Grain Coast because the Portuguese obtained from this region a species of sweet pepper known as Malagueta pepper. To the east of the Grain Coast was the Ivory Coast, where the Portuguese bought elephant tusks. 2.3 On the Lagos Lagoon, the Portuguese traded with the Ijebu. They bought slaves and elephant tusks from the Ijebu for manillas (brass bracelets). 2.4 The Portuguese had more extensive trade with the Benin Kingdom. Ughoton was the port town of Benin where the oba made arrangements to receive and control the activities of Portuguese traders. 2.5 The Portuguese had similar trading relations with the communities on the Forcados River near Warri and Bonny in the Niger Delta. *Mina means mine (gold mine). In 1482 the Portuguese constructed the fort of Sao Jorge da Mina, “Mine of Saint George or St George Mine.” The corruption of this name into its modern form, “Elmina,” occurred in the period of the Dutch occupation of the fort after 1637.