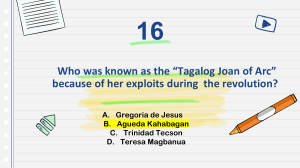

SELF-LEARNING HOME TASK (SLHT) Subject : 21st Century Literature from the Philippines and the World Grade: 11 Quarter: 2nd Week: 4 MELC: Identify representative texts and authors from South America Competency Code: EN12Lit-IIa-2 Name: School: Section: District: Date: Objective/s: Knowledge: Recognize different selections and writers from Europe Skills: Examine the given texts to comprehend the theme presented Values/Attitude: Reflect on the subjects discussed in the text and give personal views Subject Matter: Representative Texts and Authors from Europe Procedure: A. READINGS/DISCUSSIONS SELECTION 1 THE LAST JUDGMENT Karel Čapek The notorious multiple-killer Kugler, pursued by several warrants and a whole army of policemen and detectives, swore that he’d never be taken. He wasn’t either – at least not alive. The last of his nine murderous deeds was shooting a policeman who tried to arrest him. The policeman indeed died, but not before putting a total of seven bullets into Kugler. Of these seven, three were fatal. Kugler’s death came so quickly that he felt no pain. And so it seemed Kugler had escaped earthly justice. When his soul left his body, it should have been surprised at the sight of the next world – a world beyond space, grey, and infinitely desolate – but it wasn’t. A man who has been jailed on two continents looks upon the next life merely as new surroundings. Kugler expected to struggle through, equipped only with a bit of courage, as he had in the last world. At length the inevitable Last Judgment got around to Kugler. Heaven being eternally in a state of emergency, Kugler was brought before a special court of three judges and not, as his previous conduct would ordinarily merit, before a jury. The courtroom was furnished simply. Almost like courtrooms on earth, with this one exception: there was no provision for swearing in witnesses. In time, however, the reason for this will become apparent. The judges were old and worthy councilors with austere, bored faces. Kugler complied with the usual tedious formalities: Ferdinand Kugler, unemployed, born on such and such a date, died… at this point it was shown Kugler didn’t know the date of his own death. Immediately he realized this was a damaging omission in the eyes of the judges; his spirit of helpfulness faded. “Do you plead guilty or not guilty?” asked the presiding judge. “Not guilty,” said Kugler obdurately. “Bring in the first witness,” the judge sighed. Opposite Kugler appeared an extraordinary gentleman, stately, bearded, and clothed in a blue robe strewn with golden stars. At his entrance, the judges arose. Even Kugler stood up, reluctant but fascinated. Only when the old gentleman took a seat did the judges again sit down. “Witness,” began the presiding judge, “omniscient God, this court has summoned you in order to hear your testimony in the case against Kugler, Ferdinand. As you are the supreme truth, you need not take the oath. In the interest of the proceedings, however, we ask you to keep to the subject at hand rather than branch out into particulars – unless they have a bearing on this case.” “And you, Kugler, don’t interrupt the witness. He knows everything, so there’s no use denying anything.” “And now, witness, if you would please begin.” That said, the presiding judge took off his spectacles and leaned comfortably on the bench before him, evidently in preparation for a long speech by the Witness. The oldest of the three judges nestled down in sleep. The recording angel opened the Book of Life. God, the witness, coughed lightly and began: “Yes. Kugler, Ferdinand. Ferdinand Kugler, son of a factory worker, was a bad, unmanageable child from his earliest days. He loved his mother dearly, but was unable to show it, this made him unruly and defiant. Young man, you irked everyone! Do you remember how you bit your father on the thumb when he tried to spank you? You had stolen a rose from the notary’s garden.” “The rose was for Irma, the tax collector’s daughter,” Kugler said. “I know,” said God. “Irma was seven years old at that time. Did you ever hear what happened to her?” “No, I didn’t.” “She married Oscar, the son of the factory owner. But she contracted a venereal disease from him and died of a miscarriage. You remember Rudy Zaruba?” “What happened to him?” “Why, he joined the navy and died accidentally in Bombay. You two were the worst boys in the whole town. Kugler, Ferdinand, was a thief before his tenth year and an inveterate liar. He kept bad company, too: old Gribble, for instance, a drunkard and an idler, living on handouts. Nevertheless, Kugler shared many of his own meals with Gribble.” The presiding judge motioned with his hand, as if much of this was perhaps unnecessary, but Kugler himself asked hesitantly, “And… what happened to his daughter?” “What’s she doing right now?” "Mary?" asked God. "She lowered herself considerably. In her fourteenth year she married. In her twentieth year she died, remembering you in the agony of her death. By your fourteenth year you were nearly a drunkard yourself, and you often ran away from home. Your father's death came about from grief and worry; your mother's eyes faded from crying. You brought dishonor to your home, and your sister, your pretty sister Martha, never married. No young man would come calling at the home of a thief. She's still living alone and in poverty, sewing until late each night. Scrimping has exhausted her, and patronizing customers hurt her pride." "What's she doing right now?” “This very minute she’s buying thread at Wolfe’s. Do you remember that shop? Once, when you were six years old, you bought a colored glass marble there. On that very same day you lost it and never, never found it. Do you remember how you cried with rage?” “Whatever happened to it?” Kugler asked eagerly. “Well, it rolled into the drain and under the gutterspout. As a matter of fact, it’s still there, after thirty years. Right now it’s raining on earth and your marble is shivering in the gush of cold water.” Kugler bent his head, overcome by this revelation. But the presiding judge fitted his spectacles back on his nose, and said mildly, “Witness, we are obliged to get on with the case. Has the accused committed murder?” Here the Witness nodded his head. “He murdered nine people. The first one he killed in a brawl, and it was during his prison term for his crime that he became completely corrupted. The second victim was his unfaithful sweetheart. For that he was sentenced to death, but he escaped. The third was an old man whom he robbed. The fourth was a night watchman.” “Then he died?” Kugler asked. “He died after three days in terrible pain,” God said. “And he left six children behind him. The fifth and sixth victims were an old married couple. He killed them with an axe and found only sixteen dollars, although they had twenty thousand hidden away.” Kugler jumped up. “Where?” “In the straw mattress,” God said. “In a linen sack inside the mattress. That’s where they hid all the money they acquired from greed and penny-pinching. The seventh man he killed in America, a countryman of his, a bewildered, friendless immigrant.” “So it was in the mattress,” whispered Kugler in amazement. “Yes,” continued God. “The eighth man was merely a passerby who happened to be in Kugler’s way when Kugler was trying to outrun the police. At that time Kugler had periostitis and was delirious from the pain. Young man, you were suffering terribly. The ninth and last was the policeman who killed Kugler exactly when Kugler shot him.” “And why did the accused commit murder?” asked the presiding judge. “For the same reasons others have,” answered God. “Out of anger or desire for money, both deliberately and accidentally-some with pleasure, others from necessity. However, he was generous and often helpful. He was kind to women, gentle with animals, and kept his word. Am I to mention his good deeds?” “Thank you,” said the presiding judge, “but it isn’t necessary. Does the accused have anything to say in his own defense?” “No,” Kugler replied with honest indifference. “The judges of this court will now take this matter under advisement,” declared the presiding judge, and the three of them withdrew. Only God and Kugler remained in the courtroom. “Who are they?” asked Kugler, indicating with his head the men who just left. “People like you,” answered God. “They were judges on earth, so they’re judges here as well.” Kugler nibbled his fingertips. “I expected… I mean, I never really thought about it. But I figured you would judge since…” “Since I’m God,” finished the stately gentleman. “But that’s just it, don’t you see? Because I know everything, I can’t possibly judge. That wouldn’t do at all. By the way, do you know who turned you in this time?” “No, I don’t,” said Kugler, surprised. “Lucky, the waitress. She did it out of jealousy.” “Excuse me,” Kugler ventured, “but you forgot about that good-for-nothing Teddy I shot in Chicago.” “Not at all,” God said. “He recovered and is alive this very minute. I know he’s an informer, but otherwise he’s a very good man and terribly fond of children. You shouldn’t think of any person as being completely worthless.” “But I still don’t understand why you aren’t the judge,” Kugler said thoughtfully. “Because my knowledge in infinite. If judges knew everything, absolutely everything, then they would also understand everything. Their hearts would ache. They couldn’t sit in judgment – neither can I. As it is, they know only about your crimes. I know all about you. The entire Kugler. And that’s why I cannot judge.” “But why are they judging… the same people who were judges on earth?” “Because man belongs to man. As you see, I’m only the witness. But the verdict is determined by man, even in heaven. Believe me, Kugler, this is the way it should be. Man isn’t worthy of divine judgment. He deserves to be judged only by other men.” At that moment, the three returned from their deliberation. In heavy tones the presiding judge announced, “For repeated crimes of first – degree murder, manslaughter, robbery, disrespect for the law, illegally carrying weapons, and for the theft of a rose: Kugler, Ferdinand, is sentenced to lifelong punishment in hell. The sentence is to begin immediately. “Next case please: Torrance, Frank.” “Is the accused present in court?” Know that: Karel Čapek (1890-1938) was one of the most original Czech writers of the 1920s and 30s, whose works were the inspiration for much of the science fiction of Europe and America. He became famous for his symbolic fantastic plays and novels. He gave the world the word “robot” to describe mechanical characters without souls in his best-known play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) Karel had mastered the Czech language, utilizing a vast vocabulary utilized in his writings. He also employed many uncommon words and colloquial Czech without vulgarisms. In his works he asserted that each person has his or her own truth, portrayed many perspectives on reality and criticized modern society. People’s abuse of technology was another theme that often came up in his writings that appear simple but are really profound with many layers of meaning. Guide for Comprehension: Using a short bond paper, write a news report on the life and death of Ferdinand Kugler. Use the rubric below as performance indicators. Rubric A well-written news report… - has a title that tells what happened (headline). - begins with a lead that summarize the story. - answers Wh– and H-questions in the opening paragraph(s). - uses simple language - is objective in its treatment of the story. SELECTION 2 THE WASHWOMAN Isaac Bashevis Singer Our home had little contact with Gentiles. 1 The only Gentile in the building was the janitor. Fridays he would come for a tip, his “Friday money.” He remained standing at the door, took off his hat, and my mother gave him six groschen.2 Besides the janitor there were also the Gentile washwomen who came to the house to fetch our laundry. My story is about one of these. She was a small woman, old and wrinkled. When she started washing for us she was already past seventy. Most Jewish women of her age were sickly, weak, broken in body. All the old women in our street had bent backs and leaned on sticks when they walked. But this washwoman, small and thin as she was, possessed a strength that came from generations of peasant forebears. Mother would count out to her a bundle of laundry that had accumulated over several weeks. She would lift the unwieldy pack, load it on her narrow shoulders, and carry it the long way home. She also lived on Krochmalna Street too, but at the other end, near Wola section. It must have been a walk of an hour and a half. She would bring the laundry back about two weeks later. My mother had never been so pleased with any washwoman. Every piece of linen sparkled like polished silver. Every piece was neatly ironed. Yet she charged no more than the others. She was a real find. Mother always had her money ready, because it was too far for the old woman to come a second time. Laundering was not easy in those days. The old woman had no faucet where she lived but had to bring in the water from a pump. For the linens to come out so clean, they had to be scrubbed thoroughly in a washtub, rinsed with washing soda, soaked, boiled in an enormous pot, starched, then ironed. Every piece was handled ten times or more. And the drying! It could not be done outside because thieves would steal the laundry. The wrung-out wash had to be carried up to the attic and hung on clotheslines. In the winter it would become as brittle as glass and almost break when touched. Then there was always a to-do with other housewives and washwomen who wanted the attic clothesline for their own use. Only God knew all the old woman had to endure each time she did a wash! She could have begged at the church door or entered a home for the penniless and aged. But there was in her a certain pride and a love of labor with which the Gentiles have been blessed. The old woman did not want to become a burden, and so she bore her burden. My mother spoke a little Polish, and the old woman would talk with her about many things. She was especially fond of me and used to say that I looked like Jesus. She repeated this every time she came, and Mother would frown and whisper to herself, her lips barely moving, “May her words be scattered in the wilderness.” The woman had a son who was rich. I no longer remember what sort of business he had. He was ashamed of his mother, the washwoman, and never came to see her. Nor did he ever give her a groschen The old woman told this without rancor. One day the son was married. It seemed that he had made a good match. The wedding took place in a church. The son had not invited the old mother to his wedding, but she went to the church and waited at the steps to see her son lead the “young lady” to the altar. The story of the faithless son left a deep impression on my mother. She talked about it for weeks and months. It was an affront not only to the old woman but to the entire institution of motherhood. Mother would argue. “Nu, does it pay to make sacrifices for children? The mother uses up her last strength, and he does not even know the meaning of loyalty.” And she would drop dark hints to the effect that she was not certain of her own children: Who knows what they would do someday? This, however, did not prevent her from dedicating her life to us. If there was any delicacy in the house, she would put it aside for the children and invent all sorts of excuses and reasons why she herself did not want to taste it. She knew charms that went back to ancient times, and she used expressions she had inherited from generations of devoted mothers and grandmothers. If one of the children complained of a pain, she would say, “May I be your ransom and may you outlive my bones!” Or she would say, “May I be the atonement for the least of your fingernails.” When we ate she used to say “Health and marrow in your bones!” The day before the new moon she gave us a kind of candy that was said to prevent parasitic worms. If one of us had something in his eye, Mother would lick the eye clean with her tongue. She also fed us rock candy against coughs, and from time to time she would take us to be blessed against the evil eye. This did not prevent her from studying The Duties of the Heart, The Book of the Covenant, and other serious philosophic works. But to return to the washwoman: that winter was a harsh one. The streets were in the grip of a bitter cold. No matter how much we heated our stove, the windows were covered with frostwork and decorated with icicles. The newspapers reported that people were dying of the cold. Coal became dear. The winter had become so severe that parents stopped sending children to the cheder, 3 and even the Polish schools were closed. On one such day the washwoman, now nearly eighty years old, came to our house. A good deal of laundry had accumulated during the past weeks. Mother gave her a pot of tea to warm herself, as well as some bread. The old woman sat on a kitchen chair trembling and shaking, and warmed her hands against the teapot. Her fingers were gnarled from work, and perhaps from arthritis too. Her fingernails were strangely white. These hands spoke of the stubbornness of mankind, of the will to work not only as one's strength permits but beyond the limits of one's power. Mother counted and wrote down the list: men's undershirts, women's vests, long-legged drawers, bloomers, petticoats, shifts, featherbed covers, pillowcases, sheets, and the men's fringed garments. Yes, the Gentile woman washed these holy garments as well. The bundle was big, bigger than usual. When the woman placed it on her shoulders, it covered her completely. At first she swayed, as though she were about to fall under the load. But an inner obstinacy seemed to call out: No, you may not fall. A donkey may permit himself to fall under his burden, but not a human being, the crown of creation. It was fearful to watch the old woman staggering out with the enormous pack, out into the frost, where the snow was dry as salt and the air was filled with dusty white whirlwinds, like goblins dancing in the cold. Would the old woman ever reach Wola? She disappeared, and Mother sighed and prayed for her. Usually the woman brought back the wash after two or, at the most, three weeks. But three weeks passed, then four and five, and nothing was heard of the old woman. We remained without linens. The cold had become even more intense. The telephone wires were now as thick as ropes. The branches of the trees looked like glass. So much snow had fallen that the streets had become uneven, and streets sleds were able to glide down many streets as on the slopes of a hill. Kindhearted people lit fires in the streets for vagrants 4 to warm themselves and roast potatoes in, if they had any to roast. For us the washwoman's absence was a catastrophe. We needed the laundry. We did not even know the woman's house address. It seemed certain that she had collapsed, died. Mother declared that she had had a premonition, as the old woman left our house the last time, that we would never see our things again. She found some torn old shirts and washed them, mended them. We mourned, both for the laundry and for the old, toil-worn woman who had grown close to us through the years she had served us so faithfully. More than two months passed. The frost had subsided, and then a new frost had come, a new wave of cold. One evening, while Mother was sitting near the kerosene lamp mending a shirt, the door opened and a small puff of steam, followed by a gigantic bundle, entered. Under the bundle tottered the old woman, her face as white as a linen sheet. A few wisps of white hair straggled out from beneath her shawl. Mother uttered a half-choked cry. It was as though a corpse had entered the room. I ran toward the old woman and helped her unload her pack. She was even thinner now, more bent. Her face had become more gaunt, and her head shook from side to side as though she were saying no. She could not utter a clear word, but mumbled something with her sunken mouth and pale lips. After the old woman had recovered somewhat, she told us that she had been ill, very ill. Just what her illness was, I cannot remember. She had been so sick that someone had called a doctor, and the doctor had sent for a priest. Someone had informed the son, and he had contributed money for a coffin and for the funeral. But the Almighty had not yet wanted to take this pain-racked soul to Himself. She began to feel better, she became well, and as soon as she was able to stand on her feet once more she resumed her washing. Not just ours, but the wash of several other families too. “I could not rest easy in my bed because of the wash,” the old woman explained. “The wash would not let me die.” “With the help of God you will live to be a hundred and twenty,” said my mother, as a benediction. “God forbid! What good would such a long life be? The work becomes harder and harder…my strength is leaving me… I do not want to be a burden on anyone!” The old woman muttered and crossed herself, and raised her eyes toward heaven. Fortunately there was some money in the house and Mother counted out what she owed. I had a strange feeling: the coins in the old woman's washed-out hands seemed to become as worn and clean and pious as she herself was. She blew on the coins and tied them in a kerchief. Then she left, promising to return in a few weeks for a new load of wash. But she never came back. The wash she had returned was her last effort on this earth. She had been driven by an indomitable will to return the property to its rightful owners, to fulfill the task she had undertaken. And now at last her body, which had long been no more than a broken shard 5 supported only by the force of honesty and duty, had fallen. The soul passed into those spheres where all holy souls meet, regardless of the roles they played on this earth, in whatever tongue, of whatever creed. I cannot imagine paradise without this Gentile washwoman. I cannot even conceive of a world where there is no recompense for such effort. 1 a person of a non-Jewish nation or of non-Jewish faith an Austrian coin used until 2002 that is equivalent of a cent of their basic monetary unit 3 an elementary Jewish school in which children are taught to read the Torah (Jewish Scripture) and other books in Hebrew 4 one who has no established residence and wanders from place to place without lawful or visible means of support 5 shell, scrap 2 Know that: Isaac Bashevis Singer, Yiddish in full Yitskhok Bashevis Zinger, (1904-1991), PolishAmerican writer of novels, short stories, and essays in Yiddish (a German dialect which integrates many languages, including Hebrew). He was the recipient in 1978 of the Nobel Prize for Literature. His fiction, depicting Jewish life in Poland and the United States, is remarkable for its rich blending of irony, wit, and wisdom, flavored distinctively with the occult and the grotesque. He was raised in a family where everything revolved around religion (his father was a rabbi). All of his siblings, apart from the youngest, became writers. Guide for Comprehension: 1. Describe the physical features of the washwoman. 2. How did she bear “her burden” of providing for or supporting herself in order to survive? 3. What happened to her during the harsh winter ? 4. According to the washwoman, what made her stay alive? 5. What lesson does this story tell us about our duty or work? SELECTION 3 THE OLIVES Lope de Rueda Characters: TORUBIO - father AGUEDA - mother MENCIGUELA - daughter. ALOJA - neighbor TORUBIO. If not for that, I'd be home before this. AGUEDA. You don't say! And where did you plant it? TORUBIO. Close to the new-bearing figtree; you remember, where I kissed you long, long ago... (Enter MENCIGUELA.) MENCIGUELA. Come, father, everything's ready! TORUBIO. Good Lord, the storm certainly has razed the fields! All the way to the mountain clearing yonder! I remember how the bottom simply dropped out of the sky and clouds came crashing down. Well now, I wonder what that wife of mine has up her sleeve for supper – a pox on her! (calling) Agueda, Menciguela, Agueda de Toruegano! (He bangs furiously at the door.) (Enter MENCIGUELA.) MENCIGUELA. Mercy, father! Do you always have to smash doors? TORUBIO. There's a sharp tongue for you! Where's your mother, Miss Chatterbox? MENCIGUELA. She's next door, helping out with the sewing. TORUBIO. Blast her sewing and yours! Go call her! (Enter AGUEDA.) AGUEDA. Well, well! Just look our lord and master, in one of his nasty moods. What a wretched little bundle of fagots he's loaded on his back! TORIBIO. Wretched, is it, my fine lady? Why, it took two of us – me and your godson together - to lift it from the ground! AGUEDA. Hmm-well, maybe! Oh, my, you're soaking wet! TORUBIO. Drenched to the bone! But for God's sake, bring me something to eat! AGUEDA. What the devil do you expect? There's not a thing in the house. MENCIGUELA. How wet this wood is, father! TORUBIO. Of course it is. But you know your mother; she'll say it's only dew! AGUEDA. Run, child, go cook your father a couple of eggs, and make his bed. (Exit MENCIGUELA.) AGUEDA. I suppose you forgot all about the olive-shoot I asked you to plant? AGUEDA. Know what I was thinking? In six or seven years we'll have seven or eight bushels of olives, and if we plant a shoot here and a shoot there every now and then we'll have a wonderful grove in another twenty-five years. TORUBIO. Right you are, Agueda, a finelooking grove! AGUEDA. And you know what? I'll gather the olives, you'll cart them off on your little donkey, and Menciguela will sell them in the market. (turning to Menciguela) But listen to me, Menciguela, don't you dare sell a half peck of them for less than two Castilian reals! TORUBIO. Good gracious, woman! What are you talking about? Two Castilian reals? Why, such a price would give us nightmares. Besides, the market-inspector would never allow it! Fourteen, or at most fifteen dineros a half peck is quite enough to ask. AGUEDA. Bosh, Torubio! You're forgetting that our olives are the finest Cordovans in Spain! TORUBIO. Even if they are from Cordova, my price is just right. AGUEDA. Bother your prices! Menciguela, don't you sell our olives for less than two Castilian reals a half peck! TORUBIO. What do you mean, "Two Castilian reals"? Come here, Menciguela, how much are you going to ask? MENCIGUELA. Whatever you say, father. TORUBIO. Fourteen or fifteen dineros. MENCIGUELA. So be it, father. AGUEDA. What do you mean, "So be it, father"? Come here, Menciguela, how much are you going to ask? MENCIGUELA. Whatever you say, mother. AGUEDA. Two Castilian reals. MENCIGUELA. Two Castilian reals. TORUBIO. What do you mean, "Two Castilian reals"? Let me tell you that if you disobey my orders, you'll surely get two hundred lashes from me. How much are you going to ask, Menciguela? MENCIGUELA. Whatever you say, father. TORUBIO. Fourteen or fifteen dineros. MENCIGUELA. So be it, father. AGUEDA. What do you mean, "So be it, father"? (striking Menciguela) Here, take this "sobe-it" and that "so- be-it," and this, and that – that will teach you! TORUBIO. Leave the child alone! MENCIGUELA. Ouch, Mama, stop! Father, she's killing me!... Help! Help!... (Enter ALOJA) ALOJA. What's wrong, neighbors? Why are you beating your daughter? AGUEDA. Oh, good sir, this awful man is giving things away. He has made up his mind to send his family to the poorhouse. Imagine, olives as big as walnuts! TORUBIO. I swear by the bones of my ancestors that they're no bigger than pistachio nuts AGUEDA. They certainly are! TORUBIO. They are not! ALOJA. Very well, my dear lady, please do me the favor of going inside and I'll try to settle the matter. AGUEDA. You mean muddle it up worse! (Exit AGUEDA) ALOJA. Now, dear neighbor, how about the olives? Show them to me and I'll buy them all up to thirty bushels worth. TORIBIO. But you don't understand at all! You see, my friend, the olives are not here at home, they're there, out in the fields. ALOJA. If that's the case, you'll harvest them and I'll give you a fair price for the whole lot of them. MENCIGUELA. Mother says she must get two Castilian reals a half peck. ALOJA. My, my, but that's high! TORUBIO. See what I mean? MENCIGUELA. My father wants fifteen dineros per half peck. ALOJA. Show us a sample. TORUBIO. In God's name, señor, you don't seem to understand! Today I planted the shoot of an olive-tree and my wife claims that in six or seven years she'll gather seven or eight bushels. Then I'll take them to market and our daughter will sell them. She wants her to ask for two Castilian reals per half peck. But I object. My wife insists; so what with one word leading to the next, it turned into a squabble. ALOJA. A squabble, bah! The trees aren't even planted and you fools beat this poor child for quoting the wrong price! MENCIGUELA. What shall I do, señor? TORUBIO. Don't cry, darling! She's pure gold, sir. Run and set the table, and as soon as I make the first sale I'll see to it that you get the prettiest skirt in town. ALOJA. And you, neighbor, go in and make peace with your wife. (Exeunt Torubio and Menciguela.) ALOJA. O Lord, what strange things one has to witness in life! The trees haven't even been planted but everyone's up in arms about the olives! A good reason for me to put an end to my mission! ************************** end ************************* Word Guide: dinero — Spanish word for money real — coin used in Spain (Spanish peso = eight reals) peck — unit of dry measure used to rate potatoes, beans, and olives bushel — equals to four pecks Know that: A precursor of the Golden Age of Spanish literature, Lope de Rueda (1510?–1565), was a Spanish dramatist, stage director and playwright. He became popular with his numerous comedies, dramatic pastorals, religious pageants, and some forty "pasos" or one-act plays that are comic representations drawn from the events of daily life and intended to be used as humorous relief between the acts of longer works . In these skits, he featured stock characters like the braggart, the fool, the rogue, and the scholar. With these short plays, Rueda created the first popular realistic theater in Spain. The Olives, the seventh paso in El deleitoso (The Delightful), is based on the Spanish equivalent of “Don’t count your chickens before they hatch.” Guide for Comprehension: 1. How does the argument on the olives begin? 2. Have you been in a similar situation like that of Menciguela, that is, being forced to take sides in an argument? What did you do? 3. What does Aloja discover about the olives? 4. What makes the play funny? 5. Who is the most interesting character? Why do you say so? SELECTION 4 Excerpt: Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl Frank, Anne. The Diary of a Young Girl. Translated by B. M. Mooyart-Doubleday. New York: Bantam Books, 1952. Background: Anne’s diary begins on her thirteenth birthday, June 12, 1942, and ends shortly after her fifteenth. At the start of her diary, Anne describes fairly typical girlhood experiences, writing about her friendships with other girls, her crushes on boys, and her academic performance at school. Anti-Semitic (discrimination against Jews) laws forced Jews into separate schools. Anne and her older sister, Margot, attended the Jewish Lyceum in Amersterdam. The Franks had moved to the Netherlands in the years leading up to World War II to escape persecution in Germany. After the Germans invaded the Netherlands in 1940, the Franks were forced into hiding. With another family, the van Daans, and an acquaintance, Mr. Dussel, they moved into a small secret annex above Otto Frank’s office where they had stockpiled food and supplies. The employees from Otto’s firm helped hide the Franks and kept them supplied with food, medicine, and information about the outside world. The residents of the annex pay close attention to every development of the war by listening to the radio. Some bits of news catch Anne’s attention and make their way into her diary, providing a vivid historical context for her personal thoughts. The adults make optimistic bets about when the war will end, and their mood is severely affected by Allied setbacks or German advances. Amsterdam is devastated by the war during the two years the Franks are in hiding. All of the city’s residents suffer, since food becomes scarce and robberies more frequent. Saturday, June 20, 1942 My father was 36 when he married my mother, who was then 25. My sister Margot was born in 1926. I followed on June 12, 1929, and, as we are Jewish, we emigrated to Holland in 1933, where my father was appointed Managing Director of Travies NV. This firm is in close contact with the firm Kolen and Company in the same building, of which my father is a partner. The rest of our family, however, felt the full impact of Hitler’s snit-Semitic laws, so life was filled with anxiety. In 1938 after the pograms1, my two uncles escaped to the USA. My old grandmother then came to us, she was then 73. After May 1940, good times rapidly fled: first the war, then the surrender, followed by the arrival of the Germans, which is when the suffering of the Jews really began. Anti-Jewish decrees2 followed each other in quick succession. Jews must wear a yellow star. Jews must hand in their bicycles. Jews are banned from trains and are forbidden to drive. Jews are only allowed to do their shopping between three and five o’clock, and then only in shops which bear the placard “Jewish Shop.” Jews must be indoors by eight o’clock and cannot even sit in their own gardens after that hour. Jews are forbidden to visit theatres and other places of entertainment. Jews may not take part in public sports, swimming baths, tennis courts, hockey fields, and other sports grounds are all prohibited to them. Jews may not visit Christians. Jews must go to Jewish schools, and many more similar restrictions. So we could not do this and we were forbidden to do that. Jopie3 used to say to me, “You’re scared to do anything because you fear it may be forbidden.” Our freedom was strictly limited. Yet things were still bearable. Thursday, November 19, 1942 Countless friends and acquaintances have gone on to a horrible fate. Evening after evening the green and gray lorries4 roll past. The Germans ring at every front door to inquire if there are any Jews living in the house. If there are, then the whole family has to go at once. If they don’t find any, they go on to the next house. No one has a chance of evading them unless one goes into hiding. Often they go around us with lists, and only ring when they know they can get a good haul. Sometimes they let the off for cash, so much per head. It seems like the slave hunts of olden times. But it’s certainly no joke; it’s much too tragic for that. In the evenings when it’s dark, I often see rows of good innocent people, accompanied by crying children walking on and on…bullied and knocked about until they almost drop. No one is spared – old people, babies, expectant mothers, the sick – each and all join in the march of death. How fortunate we are here. So well cared for and undisturbed. We wouldn’t have to worry about all this misery were it not that we are anxious for all those dear to us that we can no longer help. I feel wicked sleeping in a warm bed, while my dearest friends have been knocked down or have fallen into a gutter somewhere out in the cold night. I get very frightened when I think of friends who have been delivered into the hands of the cruelest brutes that walk the earth. And all because they are Jews! Wednesday, May 3, 1944 Why all this destruction? The question is very understandable, but no one has found a satisfactory answer to it so far. Yes, why do they still make more gigantic planes, still heavier bombs, and at the same time, prefabricated5 houses for construction. Why should millions be spent daily on the war and yet there’s not a penny available for medical services, artists, or for the poor people? Saturday, July 15, 1944 In spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart. I simply can’t build up my hopes on a foundation consisting of confusion, misery, and death. I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness. I hear the ever approaching thunder, which will destroy us too. I can feel the sufferings of millions and yet, if I look up into the heavens, I think that it will all come right, that this cruelty too will end, and that peace and tranquility6 will return again. _____________________________________________________________________________________ 1 4 organized persecutions of Jews trucks 2 5 laws mass-produced homes 3 6 Anne’s best friend pace Know that: Born Annelies Marie Frank in Frankfurt, Germany, Anne Frank (1929-1945), a young Jewish girl, her sister, and her parents moved to the Netherlands from Germany after Adolf Hitler and the Nazis came to power there in 1933 and made life increasingly difficult for Jews. In 1942, Frank and her family went into hiding in a secret apartment behind her father’s business in Germanoccupied Amsterdam. The Franks were discovered in 1944 and sent to concentration camps; only Anne’s father survived. Anne Frank’s diary of her family’s time in hiding, first published in 1947, has been translated into almost 70 languages and is one of the most widely read accounts of the Holocaust. The Holocaust was the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its allies and collaborators. Guide for Comprehension: 1. Anne lived in a Europe with severe restrictions on Jews. She mentioned several anti-Semitic laws in this excerpt. What were some things that she mentioned in this passage which demonstrate the conditions she was living under? 2. How would you describe the tone of this excerpt? 3. Reread the paragraph written by Anne on July 15th. What are your thoughts about her feelings? 4. During this Covid 19 pandemic, what experiences do you have that are similar with Anne Frank’s? SELECTION 5 REMEMBER Christina Rossetti Remember me when I am gone away, Gone far away into the silent land; When you can no more hold me by the hand, Nor I half turn to go yet turning stay. Remember me when no more day by day You tell me of our future that you plann'd: Only remember me; you understand It will be late to counsel then or pray. Yet if you should forget me for a while And afterwards remember, do not grieve: For if the darkness and corruption leave A vestige of the thoughts that once I had, Better by far you should forget and smile Than that you should remember and be sad. Source: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45000/remember-56d224509b7ae Know that: Christina Georgina Rossetti, (1830—1894), one of the most important of English women poets both in range and quality. She excelled in works of fantasy, in poems for children, and in religious poetry. Rossetti is best known for her ballads and her mystic religious lyrics, and her poetry is marked by symbolism and intense feeling. Remember was written when she was still a teenager in 1849 but not published until 1862 when it appeared in Rossetti’s first volume, Goblin Market and Other Poems. This collection established Rossetti as a significant voice in Victorian poetry. SELECTION 6 I Live, I Die, I Burn, I Drown Louise Labé I live, I die, I burn, I drown I endure at once chill and cold Life is at once too soft and too hard I have sore troubles mingled with joys Suddenly I laugh and at the same time cry And in pleasure many a grief endure My happiness wanes and yet it lasts unchanged All at once I dry up and grow green Thus I suffer love's inconstancies And when I think the pain is most intense Without thinking, it is gone again. Then when I feel my joys certain And my hour of greatest delight arrived I find my pain beginning all over once again. Know that: Louise Labé (c. b. 1522–d. 1566) is the most well-known and celebrated woman writer of non-noble birth from the French Renaissance. While her published work (Œuvres de Louize Labe Lionnoize , 1555) is modest in length, the variety of genres she employs (epistle, sonnet, elegy, prose dialogue),… her strength of voice, and her mastery of Petrarchan (a kind of sonnet introduced by Petrarch)… conventions have made of her a hugely important figure in the literature of this period. Louise Labe was born in the early 1520s to a prosperous rope-maker, a member of the Lyon bourgeoisie. Her mother died when she was a child; her father had her educated in languages and music... Source: https://allpoetry.com/Louise-Labe Guide for Comprehension: Using the SPECS, analyze the poems you have just read. REMEMBER Subject matter of the poem: What event, situation, or experience does the poem describe or present? Purpose or theme, or message of the poet: What is the poet’s purpose in writing this? What message does she want to communicate? Emotion, or mood or feeling: What is the predominant emotion or mood of the poem? does the mood change during the poem? what emotions does the poet seek to evoke in the reader? Craftmanship or technique: What are the specific literary elements, and/or devices the poet has used in creating the poem? (rhyme scheme, figures of speech, etc.) Summary: Summarize the poem as a whole. What is the impact of the whole poem? How successful is the poem to convey emotion or feeling, ort to convey the poem’s message? I Live, I Die, I Burn, I Drown B. EXERCISES Activity Directions: Choose one selection that you like from this home task . After deciding, select one activity that you want to perform. Use another sheet of paper if needed. Text-to-Self Connection Does the text remind you of something that has happened in your life? Favorite Part What was your favorite part of the text? Why? This reminds me of _______. My favorite part of the story is ___________. Problem and Solution Write a Letter For stories only: Pick a character or persona to write What is the problem in the story and a letter. Give the character or how was it solved? persona advice or ask him/her questions. The main problem in the story is _________. Dear ______, Compare and Contrast Character Story: Describe the main character or persona. Give a reason. The main character is ________ because ________. Summary Write a summary of the text that you like. Sequence of Events Different Ending Compare a character or persona to For stories only: yourself. How are you similar and Write a different ending to a story or how are you different? write what might happen next. For stories only: What are the main events of the story? How does the story begin, develop, and end? Text-to-Text Connection Cause and Effect Lesson Learned Does the text remind you of another story or poem that you have read? Why? For stories only: Pick a part of the story that shows cause and effect. Describe what event caused another event. What lesson does the main character/persona teach you? Why is this lesson important? This reminds me of ______. The lesson is __________. C. ASSESSMENT/APPLICATION/OUTPUTS Directions: Using a short bond paper, write a slogan about the theme of the selections emphasizing how the characters and persona overcame their struggles in life. Rubric • It should start with a verb. • It can be in written in any language (English, Filipino, Cebuano). • It must contain 7-10 words including punctuation marks. D. SUGGESTED ENRICHMENT/REINFORCEMENT ACTIVITY/IES You can watch the full movie of The Diary of Anne Frank at this link https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=c25oZQrnXwc&t=11s. References: Payawal-Gabriel, Josefina. World Literature and Communication. Quezon City, Philippines: St. Bernadette Publishing House Corporation., 2014 https://www.britannica.com/biography/Karel-Capek https://www.dramaonlinelibrary.com/person?docid=person_capekKarel https://culture.pl/en/artist/isaac-bashevis-singer https://www.britannica.com/biography/Isaac-Bashevis-Singer https://www.hillsboro.k12.oh.us/userfiles/79/Classes/683/Anne%20Frank%20-%20The%20Diary%20of%20a% 20Young%20Girl.pdf https://lrobisonnet.weebly.com/uploads/2/1/3/0/21304206/diary_of_a_young_girl.pdf https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/anne-frank-1#section_2 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/introduction-to-the-holocaust https://www.britannica.com/biography/Christina-Rossetti https://poets.org/poet/christina-rossetti https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195399301/obo-9780195399301-0104.xml Prepared by: Vershyl A. Mendoza Danna Lee I. Teleron Reviewed by: Dr. Clavel D. Salinas Edited by: