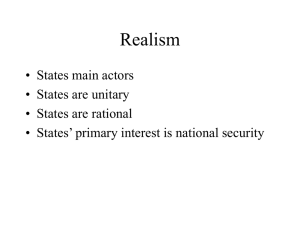

Review: Is Realism Dead? The Domestic Sources of International Politics Reviewed Work(s): War and Reason: Domestic and International Imperatives. by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and David Lalman: The Domestic Bases of Grand Strategy. by Richard Rosecrance and Arthur A. Stein: Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition. by Jack Snyder Review by: Ethan B. Kapstein Source: International Organization , Autumn, 1995, Vol. 49, No. 4 (Autumn, 1995), pp. 751-774 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2706925 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms , The MIT Press , Cambridge University Press and University of Wisconsin Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Organization This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Is realism dead? The domestic sources of international politics Ethan B. Kapstein Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and David Lalman. War and Reason: Domestic and International Imperatives. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1992. Richard Rosecrance and Arthur A. Stein, editors. The Domestic Bases of Grand Strategy. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1993. Jack Snyder. Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and InternationalAmbition. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1991. Is realism dead? Has it finally succumbed to the theoretical and empirical onslaught to which it has been subjected? If the answer is yes, which theories have taken its place? If the answer is no, what explains its durability?' I argue in this essay that structural realism, qua theory, must be viewed as deeply and perhaps fatally flawed. Yet at the same time, qua paradigm or worldview, it continues to inform the community of international relations scholars. The reason for this apparent paradox is no less sociological than epistemological. Borrowing from Thomas Kuhn, I argue that structural realism will not die as the cornerstone of international relations theory until an alternative is developed that takes its place.2 In the absence of that alternative, students of world politics will continue to use it as their cornerstone; in an important sense, structural realism continues to define the discipline. I thank Michael Desch, Joseph Grieco, Ted Hopf, Jack Levy, John Odell, Scott Sagan, Randall Schweller, and the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article. 1. In this review I use the terms "realism," "neorealism," and "structural realism" interchangeably; when I refer to the realism expressed, for example, by Morgenthau, I call it "classical realism." See Hans J. Morgenthau, PoliticsAmong Nations (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948; New York: Grosset and Dunlop, 1964). 2. Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962). For an account from the "sophisticated falsificationist" perspective, see, for example, Imre Lakatos, The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1978), especially pp. 31-47. International Organization 49, 4, Autumn 1995, pp. 751-74 ? 1995 by The 10 Foundation and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 752 International Organization The books under review mark a continuation of past efforts to attack structural realism by emphasizing the domestic sources of international relations. In so doing, each offers unique methodological approaches and an array of fascinating case studies. They raise insightful questions about the conditions under which domestic political and ideological factors can shape foreign policies that lead to such outcomes as overexpansion and war. But the central questions to be raised in this essay are: to what extent do the works under review contribute to the crucial task of theory building in international relations? Do they offer alternative theories of world politics that promise to supplant realism? If not, to what extent are the modifications provided generalizable beyond the specific cases analyzed? Or, instead, have these and other works simply led us into a period of theoretical "crisis," in which the discipline finds itself dissatisfied with existing theories but as yet unable to construct new ones?3 That the books under review seek to challenge realism on its "home ground" of national security cannot be doubted. Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and David Lalman, for example, state that "Although we set out with no preconceived notions about the relative merits of . . . realpolitik and domestic interpretations [of state behavior] ... the logic and evidence developed in this book provide a foundation for the claim that a perspective that is attentive to the domestic origins of foreign policy demands gives a richer and empirically more reliable representation of foreign affairs than a realist emphasis."4 Richard Rosecrance and Arthur Stein write: "The study of grand strategy, which deals with what influences and determines nations' policy choices for war and peace, is an ideal arena in which to examine 'realist' approaches. It is, after all, the realm in which countries should be most expected to follow realist imperatives.... And yet the findings of this volume suggest that this ... response to security stimuli does not always and may not even usually occur."5 And for Jack Snyder, ''recent exponents of Realism in international relations have been wrong in looking exclusively to states as the irreducible atoms whose power and interests are to be assessed . . . domestic pressures often outweigh international ones in the calculations of national leaders."6 In mounting their attack, the authors highlight not only the logical flaws contained in realism but also its inability to explain (much less predict) many of 3. The language is borrowed, of course, from Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. It should be noted that Kuhn did not refer to the social sciences in this work, instead limiting his claims to what he called "normal science." 4. Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and David Lalman, War and Reason: Domestic and International Imperatives (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1992), p. 9. 5. Richard Rosecrance and Arthur A. Stein, eds., The Domestic Bases of Grand Strategy (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1991), p. 12. 6. Jack Snyder, Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1991), pp. 19-20. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Realism 753 the outcomes that are of greatest interest to contemporary scholars, including the end of the cold war and the repeated failures of states to balance against threatening powers.7 That these books, which are all within the field of security studies, should point to realism's weaknesses is especially significant, for it is in that domain of international relations where its legacy probably remains the strongest. Yet I conclude that these works are unlikely to produce a "paradigm change" in international relations scholarship, for two reasons. First, none of them goes beyond its case study material to produce a generalizable alternative theory; indeed, as we will see, Snyder explicitly omits whole types of states from his analysis. Second, none of these works provides even a decisive modification of structural realism, if by such a modification we mean the generation of alternative hypotheses from existing realist assumptions (i.e., states as primary actors; anarchy as the international condition; state behavior as rational) or from a changed set of assumptions. Because of this failure, those scholars who believe that realism is dead should prepare themselves for a shock. Indeed, a notable example is Bruce Russett, who ironically borrowed Mark Twain's famous remark about the premature report of death in an article about American decline.8 Reviewing War and Reason among other books, Russett stated that "these broadsides leave a sinking hulk" where realism "once ruled the theoretical seas."9 And he quotes Zeev Maoz, who has written that system theories are "useless theoretically," "empirically meaningless," and "normatively objectionable."10 What these critiques overlook is that scholars will continue to cling to realist planks until they are rescued. In the following section, I briefly discuss what we might reasonably expect from a theory of world politics, whether it be domestically or systemically oriented. I then examine each book, highlighting both the insights and problems associated with the argumentation. I conclude by examining the status of structural realism in light of these critiques and providing some suggestions for how scholars might proceed if they seek to develop a progressive research program. 7. For further elaboration of realism's explanatory and predictive failures, with special reference to the end of the cold war, see John Lewis Gaddis, "International Relations Theory and the End of the Cold War," in Sean Lynn-Jones and Steven Miller, eds., The Cold War and After: Prospects for Peace (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1993), pp. 323-88; and Richard Ned Lebow, "The Long Peace, the End of the Cold War, and the Failure of Realism," International Organization 48 (Spring 1994), pp. 249-78. 8. Bruce Russett, "The Mysterious Case of Vanishing Hegemony: Or is Mark Twain Really Dead?" International Organization 39 (Autumn 1985), pp. 207-31. 9. Bruce Russett, "Processes of Dyadic Choice for War and Peace," World Politics 47 (January 1995), pp. 268-82. The quotations are drawn from p. 269. 10. Zeev Maoz, National Choices and International Processes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 548, quoted in Russett, "Processes of Dyadic Choice for War and Peace," p. 269. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 754 International Organization In search of theory If theories of the domestic sources of world politics are to replace or significantly modify structural realism as the cornerstone of international relations theory, they must be able not only to falsify it but also to articulate an explicit model of how a given set of domestic factors can produce particular international outcomes, the most important being war and peace. In order to take that next crucial step, they must be able to conceptualize the causal mechanisms at work that lead from the domestic factors that have been identified as critical (democratic regime type, for example) to foreign policies (for example, free trade) and to specific international outcomes (peace, for example). In other words, they must offer explanations of international relations that either work from the "inside out" or, if their more modest task is to modify structural realism, that specify the domestic process by which uncertain systemic pressures are translated into particular policy responses. Further, the theories must be generalizable beyond the case studies treated if they are to have any hope of exercising a decisive influence on international relations theory. The need for theories that incorporate the systemic and unit levels in an operational way has, of course, become an old theme within the discipline. For instance, writing in these pages some fifteen years ago, Peter Gourevitch asked: "Is the traditional distinction between international relations and domestic politics dead? Perhaps. Asking the question presupposes that it once fit reality, which is dubious."" He urged scholars to examine domestic and international politics "as a whole," and this continues to be a major, if elusive, goal.12 In the interim, the theoretical issue at stake concerns the explanatory mileage we get from adopting one particular model over another, no matter how closely its assumptions fit reality. Gourevitch noted that political scientists had adopted two major approaches for exploring the problem of how states behave with respect to their external environment. The first, most powerfully associated with but not limited to structural realism, privileges the autonomous nature of the anarchic international system and focuses on the pressures that it places on every nation-state. In this view, the foreign policies of states are best explained as a rational response to these external pressures. To be sure, the reactions of states to the international system are processed through some form of domestic intermediation. Political structures, bureaucracies, and ideas and beliefs can all play a role in shaping policy, and structural explanations often 11. Peter Gourevitch, "The Second Image Reversed: The International Sources of Domestic Politics," International Organization 32 (Autumn 1978), pp. 881-911, at p. 881. 12. For one promising contribution, however, that focuses on international negotiations, see Peter Evans, Harold Jacobson, and Robert Putnam, eds., Double-Edged Diplomacy: International Bargaining and Domestic Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), which contains a number of case studies of bargaining in both economics and security. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Realism 755 provide no more than a starting point for analyzing state behavior.13 Still, for those scholars who accept the power of a structural paradigm, the most parsimonious explanation of a country's foreign policy behavior is not found in the psychology of its leaders, its regime type, or its political ideology; instead, it is located in the relative position of the state in the anarchic international system, as measured by its capabilities-its capacity for independent action. The second approach rejects or downplays the utility of system-level theorizing. It argues either that there is no objective international system with an independent existence or that systemic pressures are so weak and uncertain that they are indeterminate with respect to the foreign policy choices that states make and the outcomes of their international interactions. In order to understand state behavior, therefore, scholars must reject the "billiard ball" model of structural realism and begin their exploration inside the "black box" of domestic politics. The causal logic of this explanation thus begins with what is happening inside a particular unit. Two brief examples, one theoretical, the other historical, seemingly provide strong support to the inside-out framework. From a theoretical perspective, the strongest inside-out alternative to structural realism would seem to be the theory of the democratic peace. A cottage industry has emerged in recent years that seeks to explain why states with democratic regimes do not go to war with one another. The word "theory," however, is a misnomer in this context, for proponents of this school have accumulated observations rather than any sustained causal logic.14 Further, even if the causal logic were established, democratic peace theory would still have a difficult time explaining the outcomes of conflicts among democratic states in such issue-areas as trade and finance. In economic relations among democracies, threats and coercion-the stuff of realist theory-are ever-present as part of international negotiations, while the value of international institutions in mitigating these conflicts may be overrated.'5 But these criticisms aside, we could hypothesize with some confidence that a world composed solely of liberal states would not confront the same type of 13. On political structures, see Peter Katzenstein, ed., Between Power and Plenty (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1978). On bureaucracies, see Graham Allison, Essence of Decision (Boston: Little, Brown, 1971). On beliefs, see Deborah Welch Larson, Origins of Containment (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1985). 14. For a critical review of democratic peace theory, see Christopher Layne, "Kant or Cant: The Myth of the Democratic Peace," International Security 19 (Fall 1994), pp. 5-49. 15. Ethan B. Kapstein, Governing the Global Economy: International Finance and the State (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1994). For a criticism of liberal institutionalism, see John J. Mearsheimer, "The False Promise of International Institutions," International Security 19 (Winter 1994/95), reprinted in Michael Brown, Sean Lynn-Jones, and Steven Miller, eds., The Perils of Anarchy: Contemporary Realism and Intemational Security (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995), pp. 332-76. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 756 International Organization security dilemma that exists when these same liberal states must coexist with authoritarian regimes, because liberal states view one another primarily as trading partners and not as potential military adversaries.16 Thus, we can argue that a multipolar world of liberal states would be more peaceful than a multipolar world consisting of different regime types, some of which are nonliberal. Absent any structural determinism, world politics closely resembles the nature of the actors who interact across borders.17 In short, regime type is a more significant determinant of international relations than polarity, or the distribution of power. An obvious historical example that would seem to support the regime type approach is provided by the German case. During the early 1930s, Hitler apparently thought-and convinced large numbers of his countrymen to believe-that a global conspiracy of Jews and Communists was preventing Germany from gaining its rightful place in the world. In the process of advancing his beliefs, he mobilized a nation that went on to conquer and occupy most of Europe. In contrast, Hitler's predecessors in Weimar Germany, who also lived in a multipolar world full of threats and challenges, generally did not believe that the country's problems could or should be solved through rearmament and the unilateral application of military force. Thus, despite the similarities of the Weimar and Nazi periods at the systemic level, very different international outcomes obtained owing to the differences in regime types. These examples should suffice to suggest the limits of structural approaches to world politics and lead us to concentrate on what drives decision making within the black box. But this has proved to be a frustrating endeavor. As Robert Putman has observed, "much of the existing literature on relations between domestic and international affairs consists either of ad hoc lists of countless 'domestic influences' on foreign policy or of generic observations that national and international affairs are somehow 'linked.' "18 Indeed, an example of such list making is provided by Rosecrance and Stein, who write in the introductory chapter of their edited volume that "domestic groups, social ideas, the character of constitutions, economic constraints (sometimes expressed through international interdependence), historical social tendencies, and domestic political pressures play an important, indeed, a pivotal role in the selection of grand strategy, and, therefore, in the prospects for international conflict and cooperation."'19 This statement is probably true, but if we are not told how to weigh these factors-to hypothesize about which 16. Richard Rosecrance, The Rise of the Trading State (New York: Basic Books, 1986). 17. For a good review of these inside-out approaches, see Randall L. Schweller, "Domestic Structures and Preventive War: Are Democracies More Pacific?," World Politics 44 (January 1992), pp. 235-69. For a skeptical view of liberalism in the European context, see John J. Mearsheimer, "Back to the Future: Instability in Europe after the Cold War," Intemational Security 15 (Summer 1990), pp. 5-56. 18. Robert Putnam, "Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games," Intemational Organization 42 (Summer 1988), pp. 427-60, at p. 430. 19. Rosecrance and Stein, The Domestic Bases of Grand Strategy, p. 5. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Realism 757 of them matters at what time-then we are left with nothing of theoretical value. We all know that theories are more than lists of independent variables: they seek to explain cause-and-effect relationships. But while some political scientists do not like to admit it, theories of social science are different from those of natural science. With few exceptions, they are historically and culturally contingent, and while the best of them may help us to explain the past, most are poor at predicting the future. Realism, with its pretensions of being a "universal" theory, provides an apparent exception; one may ask, however, whether structural realism actually stands on any firmer an empirical foundation than the inductive inside-out theories described in these pages, or whether it has provided any greater predictive power. Further, with the exception of Marxian theories, explanations in the social sciences tend to be static and fail to account for change. Structural realism provides an excellent example of a social science theory that assumes systemic continuity and does not incorporate the notion of change (although theoretical modifications, like Robert Gilpin's notion of hegemonic war, provide important exceptions).20 Despite these limitations, we should nonetheless expect social science theories to be stated clearly and the causal linkages that purport to explain events to be specified clearly.21 The first step in theory building is to determine what is to be explained. This sounds simple enough, but as I will show with respect to the books under review, a loosely stated or poorly conceptualized dependent variable can create tremendous problems for an author. Further, scholars sometimes accuse theories of failing to meet a particular test when in fact they do not purport to explain the phenomenon in question. This is an especially important issue when comparing different theories. Do theories of world politics that are rooted in domestic sources and those rooted in structural realism seek to explain the same phenomena?22 Having chosen a dependent variable, one must determine the appropriate independent variables; again, these must be clearly stated and conceptualized. Many realists, for example, use the term "power" as a key independent variable without adequately defining its meaning, a point to which I will return below.23 20. Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981). 21. Two useful recent works on social science theory are Alexander Rosenberg, Philosophy of Social Science (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1988); and Daniel Little, Varieties of Social Explanation (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1991). 22. For a model of how social scientists should compare competing theories, see Scott D. Sagan, The Limits of Safety (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1993), chap. 1. 23. On this point, see Robert Keohane, "Realism, Neorealism, and the Study of World Politics," in Robert Keohane, ed., Neorealism and Its Critics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), pp. 1-26 and p. 13 in particular. Important exceptions such as Knorr and Baldwin have made significant efforts to clarify the meaning of the term "power." See Klaus Knorr, The Power of Nations (New York: Basic Books, 1975); and David Baldwin, "Power Analysis and World Politics," World Politics 31 (January 1979), pp. 161-94. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 758 International Organization Similarly, phrases like "domestic structure" often are used rather loosely by unit-level theorists.24 In both the social and natural sciences, as Oran Young reminds us, theories "are often judged in terms of the criterion of parsimony, or, the ability to explain the maximum number of phenomena with the minimum number of assumptions of premises."25 As suggested by the ad hoc lists cited above, theories with too many variables simply become unusable or lead to spurious causation. Further, if two theories are competing to explain the same phenomena, the more parsimonious one will be preferred (assuming that it is accurate). Yet the requirement for parsimony can also stand in the way of theoretical progress. Any adequate understanding of contemporary international politics likely will require theories that are more complex than those now at our disposal.26 Finally, as Young also notes, theories may play a heuristic role "in facilitating intellectual progress by suggesting or precipitating the development of addi- tional theories."27 The theory as presented can fail on logical grounds but still generate important questions and insights. I argue below that despite its many faults, structural (or neo) realism continues to have significant heuristic value; indeed, the rich literature presented in this review was generated by puzzles that realism raises but apparently cannot answer. The failure of a theory to solve problems does not necessarily spell its demise. Anomalies occur all the time in nature that existing theories have difficulty explaining. In order to overturn a theory, one needs a new theory that does a better job of explaining both the old observations and the new observations. Part and parcel of the falsification process is alternative theory development.28 Domestic politics and war Among the books under review, only Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman's War and Reason uses formal theory or modeling techniques to bridge domestic and international politics. Those scholars supportive of the rational-choice research program will see in this book yet another reason to accept its promise as the theory of modern political science. For those who have avoided the contempo- 24. For perhaps the most influential rendering of this term, see Peter Katzenstein, "Conclusions," in Katzenstein, Between Power and Plenty. 25. Oran Young, "The Perils of Odysseus: On Constructing Theories of International Relations," in Raymond Tanter and Richard Ullmann, eds., Theory and Policy in Intemational Relations (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972), p. 181. 26. I thank John Odell for highlighting this point. For more on theorizing in the social sciences, see Robert Keohane, Gary King, and Sidney Verba, Designing Social Inquiry (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994). 27. Young, "The Perils of Odysseus," p. 182. 28. On this point, see Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; and Lakatos, The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Realism 759 rary rational-choice literature owing to math phobia, Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman surely are among the most accessible scholars working this vein. The arguments of the book can be clearly discerned without a sophisticated mathematics background, and that is to the authors' credit. What are the authors trying to explain in War and Reason? Their dependent variable seems to be whether or not wars "arise from considerations contrary to the general welfare." Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman state that the general welfare (which is defined as security against foreign incursion) "concerns the connection between the goals of the citizenry and the objectives and actions of ... statesmen. Have leaders chosen the best course of action ... to enhance the welfare of the people?"29 War and Reason is an ambitious book, and the authors are trying to address one of the central issues in the literature: whether states go to war because external pressures have weighed so heavily upon them as to give them little or no choice if they wish to survive (the structural realist approach) or because domestic political factors have led states to aggression (the domestic sources approach). To once again cite the example of Germany, was it structural pressures that led the Nazis to wage war, or unit-level factors? If the former, why did the Weimar Republic not declare war? Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman's effort to construct a formal test of these alternatives should be applauded, but as we will see below their simplification of realist theory undermines their analysis. In essence, Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman begin their test by treating structural realism as the "pure theory" of international politics, and the authors ask whether or not the foreign policies of states diverge from its predictions about how they should behave in an anarchic environment. More narrowly, the authors focus on balance-of-power theory, for, as Kenneth Waltz wrote, "If there is any distinctively political theory of international politics, balance-of-power theory is it."30 The authors test balance-of-power theory by modeling an international interactions game, which is really at the heart of the book. The game itself is simple and clearly explained and is illuminating in several respects. Indeed, their explication should be required reading for all formal theorists who seek a wider audience for their scholarship. In setting up the game, Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman contrast the realist view of foreign policy with a domestic-political view. According to them, "the realist view . . . suggests that leaders select policies vis-'a-vis putative rivals to maximize the welfare of their own state (and presumably themselves) in the foreign policy context."13' In the domestic politics model, the "key foreign policy leader . . . is not charged with defining the aims of foreign policy. These aims 29. Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman, War and Reason, p. 3. On the definition of welfare, see ibid., p. 12. 30. Kenneth Waltz, Theory of International Politics (New York: Random House, 1979), p. 117. 31. Ibid., p. 17. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 760 International Organization originate from the domestic political process." As the authors themselves admit, the "domestic political process" is never defined adequately in the book and remains something of a mystery. In their international interactions game, they build a model that is supposed to demonstrate the differences between the realist and domestic political approaches. The model is based on six assumptions that are common to both theoretical variants: that strategies are chosen to maximize expected utility; that the ultimate change in welfare resulting from a war or from negotiation is uncertain (that is, it is difficult to know in advance whether one will be better off on the basis of negotiating or going to war); that losses in war are certain; that nations prefer to attain their objectives through negotiation rather than war; that acceding to foreign demands is less desirable than the status quo, which is less desirable than gaining one's demands; and that "each outcome has a set of potential benefits and/or costs appropriately associated with it."32 The international interactions game has two proper subgames, which are of greatest interest. These crisis subgames arise when state A does not capitulate to state B's demand to change the status quo. In their most significant finding, Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman argue that, using their realist assumption in which the leader is unconstrained by domestic political forces, the only rational outcomes for the actors are either negotiation or continuation of the status quo. Thus, realism does not explain the most important outcome of world politics, namely the decision for war. The study of war and peace, therefore, must focus by default on domestic politics. How do the authors reach this remarkable conclusion? The logic is as follows. Take two states A and B, with identical preference structures. They each prefer the status quo (SQ) to acquiescence (A) to the other country's demands, and acquiescence to capitulation (C) following the use of military force; thus SQ > A > C. A negotiated settlement (N) to the dispute, however, is also preferred to acquiescence and capitulation; thus N > A > C. Given this preference ordering, rational actors with complete information about the risks associated with the use of force will either maintain the status quo or seek a negotiated settlement; the other alternatives-acquiescence or capitulationclearly are inferior. In short, if war arises from a crisis it must be because of factors located at the unit level, since structural pressures generate a status quo preference. In modeling this interaction, Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman have turned structural realist theory on its head. Realists generally believe that wars happen because there is no central power to prevent their occurrence. In contrast, Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman argue that realist logic actually points in the opposite direction: structural pressures should act to prevent wars, but they are overpowered by "irrational" domestic political forces. 32. Ibid., p. 40. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Realism 761 This compelling argument suffers from several problems, and here I focus on two: first, the authors' misunderstanding of realist theory; and second, the assumptions underlying their international interactions game.33 For contemporary structural realism, what happens when states become aggressive or revisionist?34 The most important hypothesis is that other states will balance against the threatening power; thus, any rational state that seeks to dominate its neighbor should expect a coalition to rise up against it. But if a state knows that a balancing coalition of equal or greater power inevitably will form, then it should negotiate or remain content with the status quo. Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman remind us, however, that balances do not always form, at least in time to prevent war. This failure is, according to the authors, inexplicable by realist logic. But no realist ever claimed that balances occur automatically; that is, in time to prevent war or save a given international-political structure from crumbling. States often are slow to recognize threats; the United States only went to war in 1941 after being victimized by Japan's surprise attack at Pearl Harbor. Further, alliances may not form quickly because states will engage in buck-passing-an effort to get other states to bear the greatest burden of the conflict.35 Indeed, given the temptation to free ride the question for realists is: why do alliances ever form at all, and this is also a question that revisionist leaders may ask when they make their decision for war. Do not such leaders generally expect to divide and conquer their enemies?36 What this suggests is that the rational leader may choose to start a limited war if it seems unlikely that a balance will form to stop the aggression; in fact, the leader would expect a countervailing balance to form only when and if the revisionist state threatens the existing international order. The puzzle thus becomes: why do states sometimes overexpand (go too far), causing other states to create such counterbalances? (This is the very puzzle that Jack Snyder explores in Myths of Empire.) The point about limited war, in turn, suggests that one of Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman's major assumptions should be challenged: namely, that states always prefer negotiation to war. On the one hand, one could argue that such an assumption skews their results: if we assume that states prefer negotiation to 33. Bueno de Mesquita used many of the same assumptions as the basis for his earlier book, The War Trap (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1981), and at that time a number of fundamental criticisms were raised. See, for example, Yuen Foong Khong, "War and International Theory: A Commentary on the State of the Art," Review of Intemational Studies 10 (January 1984), pp. 41-63. I thank Scott Sagan for bringing this article to my attention. 34. Randall Schweller, "Bandwagoning for Profit: Bringing the Revisionist State Back In," Intemational Security (Summer 1994), pp. 72-107. 35. Thomas J. Christensen and Jack Snyder, "Chain Gangs and Passed Bucks: Predicting Alliance Patterns in Multipolarity," Intemational Organization 44 (Spring 1990), pp. 137-68. 36. For a discussion of the standard realist response and views on this subject, see Steven Walt, "Alliances, Threats, and U.S. Grand Strategy," Security Studies 1 (Spring 1992), pp. 448-82 and p. 449 in particular. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 762 International Organization war we should not be surprised if this result flows from their game. On the other, it could be that states that prefer negotiation will nonetheless get war, in prisoners' dilemma fashion.37 The authors could have clarified better how these contending perspectives play out. More important, states may actually prefer war to negotiation for the following reasons: first, to take advantage of strategic surprise; second, because war may create a bandwagon effect that tips the international balance in the state's favor; and finally, because war is seen as preferable to negotiation as a means, given the state's broader strategic ends (e.g., to demonstrate its military force to potential challengers).38 These critiques, however, should not obscure War and Reason's contribution to the literature. Its effort to test realist versus domestic-political theories and its blend of (clearly explicated) formal modeling with historical examples provide a useful example for scholars working in this genre. Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman have sought to address some of the major theoretical and empirical issues in international relations, and if they have not provided alternative theories they have at least written a thought-provoking tour d'horizon. Domestic politics and overexpansion Whereas Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman have attempted to launch a spare and logical attack on structural realism in War and Reason, Snyder has provided a rich and complex battery of evidence in Myths of Empire. Snyder provides an ambitious account of the "overexpansion" of the major great powers since the nineteenth century-an expansion that led to the creation of countervailing balances of power. The author claims that his account is consistent with a modified realist position; that is, a modification that fully incorporates domes politics. Indeed, the book blasts open the black box of the state in an effort to uncover the interest groups that promote particular foreign policy decisions.39 As noted above, Snyder has chosen a good puzzle for careful readers of realist theory, since we would expect rational leaders to halt their aggression before causing balances to form against them. The international environment permits aggression, but systemic factors alone do not explain why overexpansion occurs. For this, Snyder argues, we need to understand the dynamics of policy formation within the nation-state, and especially the role of competing interest groups within various political structures. In developing his domestic-political explanation for overexpansion, Snyder draws heavily on Alexander Gerschenkron's distinction between early and late 37. I thank an anonymous reviewer for highlighting this point. 38. On the bandwagon effect, see Schweller, "Bandwagoning for Profit." The bandwagoning hypothesis, of course, opposes the neorealist hypothesis that the international system tends towards balance. 39. For a penetrating review essay on Snyder, see Fareed Zakaria, "Realism and Domestic Politics," Intemational Security 17 (Summer 1992), pp. 177-98. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Realism 763 industrializers. The early industrializers-namely Britain and the United States-were less prone to overexpansion because their political systems were resistant to "cartelization" and capture by a small number of interest groups; instead, a variety of contending interests clashed in the domestic political sphere. But in late industrializers, like Germany and Japan, a coalition of powerful economic and political interest groups, which shared a desire for geographic expansion, were able to capture the government and cartelize policy formation. The "myth of empire"-or of the state's alleged need to engage in imperial expansion-was thus created by those groups that favored such expansion for political and/or economic reasons. Unfortunately, in the process of logrolling political favors, the demand for expansion got out of hand, and overexpansion resulted; overexpansion, or the provoking of a countervailing balance, was an outcome that no single group wanted but that the coalition-captured government was unable to prevent. This snowball theory of overexpansion has some significant problems. I will focus on two of them: first, its generalizability; second, its utility in modifying realism. Snyder himself does not make any claims for the generalizability of his approach. For example, he argues that it is difficult to know a priori what a dictator will do with respect to foreign policy, given his or her complete control of the political system. To be sure, some dictators, such as Hitler, have pursued expansionist policies that ultimately provoked a response by other great powers. But other dictators, like Franco, have focused their political machinations on the domestic front. Thus, Snyder's model does not purport to explain some of the most interesting and important cases of state behavior in international history. Snyder's analysis also seems to work better for his historic as opposed to his contemporary cases; perhaps this says something about the value of a historical perspective. For example, he contrasts the overexpansion of Germany and Japan in the 1940s with the relatively moderate geopolitical behavior of the Soviet Union and the United States during the cold war. But to assert that the Soviet Union did not overexpand is dubious, since Stalin's postwar policies led to the creation of a balancing coalition that incorporated a majority share of the world's gross product and included the United States and all of Western Europe (along these lines, one wishes that the author had hypothesized about China's likely geopolitical evolution). With respect to the United States, one could argue that a Soviet-led counterbalance was indeed created during the cold war in response to U.S. expansion in Western Europe; and looking to the future, some scholars posit that a new balance eventually will form to counter America's current position of hegemonic power.40 To state that Snyder's approach is not generalizable is not to reject its value. Most social science theories are historically contingent, and scholars of 40. See, for example, Christopher Layne, "The Unipolar Illusion: Why New Great Powers Will Rise," Intemational Security 17 (Spring 1993), pp. 5-51. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 764 International Organization international relations may eventually decide that this is the best they can achieve. If that is the case, however, to what extent can we say that Snyder successfully has modified structural realism, a theory that does have pretenses of universal significance? At a minimum, any modification of realism would have to retain the insights that it does contribute to our understanding of world politics, but this is not the case if we adopt Snyder's model. Take the case of "strange alliances," such as those that form between democratic and nondemocratic powers or among authoritarian regimes. Snyder's theory of alliances is as follows: "States with myth-resistant domestic political orders behave in accord with the tenets of defensive Realism. They form defensive alliances to contain the expansion of aggressive states."'41 Since the behavior of dictatorships cannot be predicted, however, the theory would not enable us to explain the most puzzling (from a unit-level perspective) alliance of modern times: that between the Soviet Union and the United States to check Hitler. Realism does a better job of predicting alliances between democracies and dictatorships when they share a common enemy. And what about the behavior of states prone to adopt the myths of empire? For these states, Snyder says, we need to adopt a different variant of realism, which he labels "aggressive realism." These revisionist powers are not satisfied with the status quo and engage in overexpansion. Their behavior can be understood only by opening the black box of domestic politics. But how does such an approach help us understand the alliance behavior of revisionist states, such as those between Germany and Japan during World War II, or the Nazi-Soviet nonaggression pact? Snyder's theory also fails the parsimony test. Again, as stated at the outset of this review, the value of parsimony is probably overstated by international relations scholars-especially when it applies to theories that patently fail to explain outcomes in world politics. But an examination of Snyder's cases suggests that a simple, realist explanation of overexpansion may have yielded a significant amount of explanatory power. Snyder admits as much when he writes, "in several cases a state's position in the international system correlated roughly with its propensity to overexpand."42 In his commentary on Myths of Empire, Fareed Zakaria also has pointed out that a "spare systemic explanation" can explain the outcome of each country study (namely, imperial Germany, 1930s Japan, Victorian Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union) that Snyder covers.43 Contrast the examples of British and Japanese expansion. During the nineteenth century, Zakaria reminds us, Britain was the world's superpower, controlling the sea lanes, international finance, and a large share of global wealth. With the defeat of 41. Snyder, Myths of Empire, p. 12. 42. Ibid., p. 307. 43. Zakaria, "Realism and Domestic Politics." This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Realism 765 Napoleonic France, it faced no serious European challengers for fifty years, and it expanded thereafter in gluttonous fashion; as Randall Schweller has remarked, "the appetite of great powers grows with the eating."44 In short, Britain expanded because nothing stopped it, including domestic politics. Japan, in contrast, was a growing regional power that relied on imports for almost all its raw materials, including oil from the United States and minerals from various British colonies.45 In trying to secure its supplies in a world of competing economic blocs (for example, the British-led sterling bloc, the protectionist policies of which even enraged the United States as late as the Marshall Plan years), Japan engaged in a policy of imperial expansion with the objective of creating a so-called co-prosperity sphere of its own.46 Ultimately, this policy collided with that of the United States, a nation with much greater economic and military capabilities than Japan. Relative power explains the outcome of this ill-fated expansion episode.47 Snyder would respond that realism still does not tell us anything about the possible sources of such policy behavior. If the above statements about relative power are true, why then did Japan seek to conquer all of east Asia, much less attack the United States? Why did it not maintain a limited-war strategy? If Japan had been a rational actor, would not it have avoided a direct conflict with a much more powerful state? Indeed, historians have demonstrated that many Japanese officials had powerful doubts about their country's course of action and accurately predicted that its aggressive policies must end in ruin.48 The challenge for such a perspective is to make a convincing case that an alternative paradigm was available to Japanese decision makers for their consideration in light of the international conditions that were present. Snyder points out, for example, that in the mid-1920s liberals and conservatives engaged in a lively debate over Japanese foreign policy. But he observes that the liberals' position was severely undermined by the closure of markets around the world during the Great Depression. As he writes, "At the end of the 1920s, depression and protectionism helped kill ... democracy."49 This suggests that Japanese militarism and overexpansion were, at a minimum, aided and abetted by how other countries were coping with economic decline; that is, by systemic pressures. Thus, the more threatening the external environment, the more warlike the domestic environment. (Ironically, rearmament played a useful role 44. Randall Schweller, personal communication, 28 March 1994. 45. On Japan's economic dependence and its related military strategy, see Alan S. Milward, War, Economy and Society: 1939-1945 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), pp. 30-36. See also Michael Barnhart, Japan Prepares for Total War (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1987). 46. On Anglo-American friction over the sterling bloc, see Ethan B. Kapstein, The Insecure Alliance: Energy Crises and Westem Politics Since 1944 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), chap. 2. 47. Zakaria, "Realism and Domestic Politics." 48. See, for example, Barnhart, Japan Prepares for Total War. 49. Ibid., p. 151. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 766 International Organization in economic recovery in Japan and elsewhere by the eve of World War II, but this rearmament also increased the level of global insecurity.)50 Overall, Myths of Empire provides a fascinating account of the domestic politics of five nations during those periods when they were undergoing intense economic and political change and of how such changes favored the interests of certain organized groups in society. It is unlikely, however, that the complex, Gerschenkronian model presented in the book will provide either the cornerstone for a new paradigm of international relations or even lead to a decisive modification of structural realism-especially in light of Snyder's failure to explain the behavior of dictatorships. Further, he does not make a convincing case for the marginal theoretical (as opposed to historical) value of his model. If state actions can be broadly understood as a response to systemic pressures, and if outcomes can be broadly understood as the product of relative power capabilities, it is a priori unclear how much explanatory leverage we would gain by adopting Snyder's approach as opposed to a more parsimonious systemic account. Domestic politics and grand strategy For Snyder, the constellation of domestic political forces rather than power capabilities provides the key to understanding state behavior in the international system. The essays in The Domestic Bases of Grand Strategy further complicate the picture by suggesting that, in addition to such forces, beliefs, constitutions, economic conditions, and ideas all can influence the shape and execution of national security policy. Each essay is well-written, and most are relatively persuasive on a stand-alone basis; unfortunately, in the interests of space they cannot all be described in this article. But the volume provides us with a series of theoretical appetizers rather than a meal, and no overall framework is provided that would guide us through such fundamental questions as, which of the cited influences is most important, and why? Each essay finds as its starting point the failure of structural approaches to explain particular policy outcomes; of course, most neorealists would probably respond that their theory does not try to explain the details of unit-level decision making. Thus, in his study of the cold war, John Mueller asks why it ended in 1985 (the year the cold war ended, like the year in which it began, will no doubt fuel historic controversy for generations to come) despite the fact that Soviet economic and military capabilities were not far different from their 1981 levels? Thus, well before the demise of Mikhail Gorbachev and the Soviet empire, the Soviet Union and the United States were speaking about the war's 50. On the role of rearmament in economic growth, see Charles Kindleberger, A World in Depression: 1929-1939 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973); and Alan S. Milward, War, Economy and Society: 1939-1945 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977). This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Realism 767 end and the implications of that change for world peace.51 Such momentous changes, Mueller argues, are inexplicable by realist logic, and he tells us that "the grand strategies of the major contestants ... were chiefly determined by differences in ideas and ideologies that emanate from domestic politics, not by structural differences in the distribution of capabilities at the international level."52 But what were the differences between the cold war strategies of the Soviet Union and those of the United States? Did they each not form large blocs that confronted one another? Did they each not fight wars on their peripheries? And was their contest not ultimately decided by relative power capabilities? Again, Mueller's approach may supplement a realist account, but he does not supplant much less modify one. In his essay, Arthur Stein states that neorealism fails to illuminate U.S. security policy during two crucial periods-the 1930s and late 1940s-and suggests that "domestic politics underlay an incoherence in U.S. grand strategy."53 For Stein, the puzzle is found in U.S. "underextension" in the interwar years, followed by overextension in the postwar era. That is, U.S. foreign commitments were less extensive than its capabilities would have permitted during the 1930s but more extensive than its capabilities warranted in the late 1940s, following massive troop demobilization after World War II. The failure of U.S. grand strategy in the interwar years, says Stein, contributed to the eruption of World War II, while the postwar gap between commitments and fielded capabilities provided a permissive environment for Soviet expansion and the Korean invasion. The lag between the perception of threats to the balance of power and the implementation of policies to counter those threats provides a challenge, Stein asserts, to structural realism, and is found in the complex interplay of domestic political forces. Again, besides challenging some of Stein's historiography (the United States did begin to engage in a substantial military buildup during the late 1930s, as measured by defense budgets and industrial mobilization policies), most realists would accept that such lags occur all the time; what matters to them is that great powers respond eventually. In their study of British grand strategy during the 1930s, Rosecrance and Zara Steiner turn Stein's analysis on its head.54 Great Britain, they argue, lacked the economic and military capabilities to challenge Hitler in the late 1930s, but it did so anyway (they seem to overlook the fact that Britain was first tacitly and later explicitly allied with France during most of this period, and 51. John Mueller, "The Impact of Ideas on Grand Strategy," in Rosecrance and Stein, The Domestic Bases of Grand Strategy, pp. 48-64, and pp. 54-55 in particular. 52. Ibid., p. 48. 53. Arthur Stein, "Domestic Constraints, Extended Deterrence, and the Incoherence of Grand Strategy, 1938-1950," in Rosecrance and Stein, The Domestic Bases of Grand Strategy, pp. 96-123. The quotation is drawn from p. 97. 54. Richard Rosecrance and Zara Steiner, "British Grand Strategy and the Origins of World War II," in Rosecrance and Stein, The Domestic Bases of Grand Strategy, pp. 124-153. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 768 International Organization that their combined resources were probably greater than those available to Hitler's Germany).55 They argue that this policy decision, seemingly at odds with neorealist predictions, was due to a change in "cognitive beliefs" within the British polity about Hitler's objectives and the possibility of meeting them through peaceful accommodation.56 While Britain's economic and military situation, they say, should have dictated a continuation of the appeasement strategy and further negotiation (as Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman's model of realist theory would predict), the country accepted an alliance with countries that it could not defend (France, Poland) and found itself in a war that it could not win on its own. To be sure, all the essays described above suggest the importance of enriching realist explanations with domestic-level analyses. But who would quarrel with that? No serious scholar disputes the importance of ideas, beliefs, and domestic political factors in shaping foreign policies. The more crucial question for our purpose, however, is, what is the underlying theory here? In what ways have the authors advanced our understanding of domestic and international politics as a whole? In that regard, perhaps the most useful essay in the volume is Matthew Evangelista's contribution on Soviet grand strategy.57 As with the volume's other contributors, Evangelista discovers serious anomalies between realism's predictions about state behavior and actual Soviet policies. But Evangelista goes beyond a mere critique of existing theories to suggest a new paradigm that incorporates structural and unit-level approaches. Further, the insights generated in the essay are policy-relevant in the best sense of that term: they raise significant questions about U.S. foreign policy during the cold war and whether other roads could have been taken that would have promoted those moderates working within the Soviet government. Evangelista opens his essay by noting the contradictions in two accounts of Soviet behavior by Waltz written in 1981 and 1990. In 1981, Waltz claimed that relative Soviet weakness vis-a-vis the United States had led it to invest massive sums in military power; in a 1990 essay he claimed that relative Soviet weakness had led it to seek accommodation with the West; thus, at one time weakness led to an effort to catch up, while a few years later it led to negotiation.58 This, Evangelista says, is puzzling, since the sharpest drop in Soviet economic output relative to the United States occurred in neither the late 1970s nor 1980s but in 55. I thank Randall Schweller for highlighting this point. 56. Ibid., p. 126. 57. Matthew Evangelista, "Internal and External Constraints on Grand Strategy: The Soviet Case," in Rosecrance and Stein, The Domestic Bases of Grand Strategy, pp. 154-78. 58. See Kenneth Waltz, "On the Nature of States and Their Recourse to Violence," United States Institute for Peace Joumal 3 (June 1990), pp. 6-7; Kenneth Waltz, "Another Gap," Policy Papers in International Affairs, Institute for International Affairs, Berkeley, Calif., 1981, pp. 79-80, cited in Evangelista, "Internal and External Constraints on Grand Strategy " pp. 157 and 160. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Realism 769 the early 1970s, which was a time of detente on the one hand and a continued Soviet military buildup on the other.59 Thus, changes in capabilities do cause changes in behavior, but the direction of that behavioral change is indeterminate. Taking this as his starting point, Evangelista then opens the black box of domestic politics to relax realism's unitary actor assumption. He suggests that policymakers are in fact aware of their relative economic position in the international system and of the degree of military threat posed by other actors. What public officials debate, however, is the appropriate policy response to the international environment in which they find themselves. And that policy response is shaped not merely by relative capabilities but by the foreign policies of other states in the system. Evangelista labels this approach "postrealist," and argues "that if the leaders of one country, such as the United States, understand the nature of internal foreign policy debates in a rival country, such as the former Soviet Union, they can tailor their own policies to try to influence the outcome of debates in the rival country and, consequently, their rival's behavior. Thus, in considering how postrealist analysts would relate the external environment to Soviet economic constraints we should look beyond a simple dichotomy of perceptions of high versus low threat to consider internal Soviet disagreements about U.S. behavior."60 Evangelista's assumption that foreign policy decisions in country A will produce a reaction in country B is hardly original. What is intriguing, however, is the idea that the foreign policy decisions taken in country A can decisively influence the politics of B's internal debates over how best to respond. In other words, he emphasizes that policy interactions between two states are not predetermined and that a significant scope for choice is possible. Foreign policies in country A, he argues, can favor either moderate or hard-line forces in country B. In the case at hand, he states that the United States generally pursued cold war policies that favored hard-liners in the Soviet Union, and that it lost several opportunities to promote the moderates in power, especially during the Khrushchev years. On a more hopeful note, however, he suggests that the American government's policies toward Presidents Gorbachev and Yeltsin have been sensitive to promoting the moderates at work in Russia. The problem with this approach is that it easily leads to a chicken-and-egg situation, since one could argue that it was really Soviet policies under Stalin that encouraged hard-line responses by the United States in the first place. After all, postwar America engaged in a rich debate over how diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union should be pursued, a debate that led, among other things, to the firing of Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace from the 59. Ibid., pp. 157-60. 60. Ibid., p. 170. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 770 International Organization Truman administration and the near-split of the Democratic party.6" It was Stalin, so goes this line of argument, rather than conservatives in the U.S. government, who forced the United States to adopt policies such as those found in NSC-68, one of the cold war's founding documents.62 Should Evangelista pursue this postrealist approach, one hopes that he will provide us with some guidance as to how we might resolve these types of deadlocks with respect to action-reaction functions. In generating their various puzzles, the essays in the Rosecrance and Stein volume, like War and Reason and Myths of Empire, seemingly provide further evidence against the explanatory and predictive power of structural realism. They call into question both that theory's operating assumptions and its analysis of state behavior. And while many of the critiques fault neorealism for claims it never makes, some essays raise serious questions that must be confronted by realist scholars if they wish to continue defending the theory's utility. This issue will be treated in more detail in the following section. Nonetheless, the works under review are markedly less successful in providing the reader with a well-articulated alternative to the realist paradigm or even to useful modifications of it in anything but ad hoc fashion. While several of the authors provide useful supplements to realist accounts, those who reject realism outright must leave us with something more, for example, than the finding that "ideas matter." Evangelista's chapter represents a partial and welcome exception in this regard, but postrealism will need significant development before it can be viewed as a viable paradigm in its own right. Is realism dead? Despite its weaknesses, structural realism somehow remains standing as the only paradigm that purports to explain the insecure nature of the anarchic international environment and the behavior of the states within it over the broad sweep of history. From its core assumptions about the system and its units, it draws a number of hypotheses. Unfortunately, the books under review suggest serious flaws in both its assumptions and its hypotheses, leading to questions about the theory's utility if not durability. Of all realism's assumptions and hypotheses, probably the most disputed concern rationality and balancing behavior. For example, the rationality 61. Deborah Welch Larson, Origins of Containment (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1985), On the firing of Wallace, see pp. 288-94. 62. National Security Council document number 68 (NSC-68), written in 1950, provided the rationale for a new American military buildup in the wake of the rapid demobilization that had followed the end of World War II. According to historian John Lewis Gaddis, "What NSC-68 did was to suggest a way to increase defense expenditures without war, without long-term budget deficits, and without crushing tax burdens." NSC-68 has been viewed by historians as a founding document of U.S. cold war strategy. See John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), p. 93. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Realism 771 assumption is questioned by nearly all the authors discussed here, and even those scholars who find it useful continue to debate its meaning.63 Are states rational in the economic value-maximizing sense of the term, or in the psychological satisficing sense? If a state can choose between balancing for security or banding together for gain, what is the rational policy to adopt? Can states learn from past experiences? As stated above, the insistence of theorists on using concepts like rationality without fully defining them and showing their operational value can only hinder the field's progress. And what about the balancing hypothesis, which is attacked by several of the authors discussed herein (for example, Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman)? Waltz, of course, argued that states balanced against capabilities, while his student Steven Walt suggested that they balance against threat.64 Other scholars have suggested that balancing occurs against land powers, not naval powers.65 In contrast, Schweller asserts that the prevalence of balancing has been overstated, to the neglect of "bandwagoning" behavior. Schweller says states are motivated to side with the stronger party (bandwagon) "by the prospect of making gains."66 In short, the most significant neorealist hypothesis remains contested. From a broader theoretical perspective, one may question the analogy between structural realism and microeconomics. Waltz, for example, has written that "balance-of-power theory is microtheory precisely in the economist's sense. The system, like a market in economics, is made by the actions and interactions of its units, and the theory is based on assumptions about their behavior."67 However, the international system, as Waltz describes it, operates nothing like a competitive marketplace, and it is wrong to argue, as he does, that the international system generates pressure on states in the same way that markets generate pressure on firms.68 If this is true, why do relatively few states disappear or "go out of business?" Further, the balance of power, to the extent that it does become operational, unwittingly acts to maintain the system of states. This, of course, would be unheard of in economics, where "creative destruction" is an ongoing process.69 63. For a critical review of the literature on rationality, see Jack Snyder, "Rationality at the Brink," World Politics 30 (April 1978), pp. 345-65. For a sympathetic overview, see Edward Rhodes, Power and MADness (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989), pp. 47-81. For competing treatments of the balance of power, see, among others, Edward Vose Gulick, Europe's Classical Balance of Power (New York: Norton, 1955); Hans Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1993 orig. 1948), pp. 183-216; Steven Walt, Origins of Alliances (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1987); and Schweller, "Bandwagoning for Profit." 64. See Waltz, Theory of International Politics; and Walt, Origins ofAlliances. 65. I thank Jack Levy for highlighting this point. See Jack Levy, "Theories of General War," World Politics 37 (April 1985), pp. 344-74. 66. Schweller, "Bandwagoning for Profit," p. 24. 67. Waltz, Theory of International Politics, p. 118. 68. Waltz, Theory of International Politics. Zakaria also accepts the value of this analogy in "Realism and Domestic Politics," pp. 193-95. See also Barry Buzan, Charles Jones, and Richard Little, The Logic ofAnarchy (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), pp. 192-94. 69. Edward Vose Gulick, Europe's Classical Balar.ce of Power (New York: Norton, 1955). This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 772 International Organization Perhaps of greatest importance, economic systems are regulated by states, whereas the international system is anarchic. Realist theory, then, appears flawed in many important respects. As a result, the study of international relations is now in something of a crisis stage: the existing paradigm appears to be of limited value, but no strong contenders provide a viable alternative. We know that domestic politics "matter," but we still do not know how to treat domestic and international politics as a whole. It is thus not surprising that the field has found itself mired in debates that are taking an increasingly strident and even ideological tone: whether states seek relative or absolute gains, or whether particular scholars adopt a realist or liberal institutionalist perspective in their work. Adopting extreme positions may be professionally useful, but one wonders how helpful it is for illuminating our object of study, namely state behavior. A positive research program should not abandon realism but should continue to build on and refine its basic analysis of the relationship between system and unit. Most scholars of international relations probably accept that one of the defining features of their field of study is that the interactions of the units take place in an anarchic environment, an environment without any central, governing authority. What they dispute are the implications of anarchy for state behavior. For Waltz, the crucial independent variable within this environment is the distribution of power; namely, whether it is bipolar, unipolar, or multipolar. But a significant debate has erupted about the definition of polarity, as exemplified by a set of recent articles that take contending views on the distribution of power in the contemporary system.70 With the end of the cold war, the concept of polarity seemingly has become even more confused; a positive research program would reexamine this concept and possibly redefine it, perhaps incorporating notions of state type. This interplay between polarity and regime type goes to the heart of the debate among systemic and domestic politics approaches. A priori, realists would predict that a bipolar world, irrespective of state type, would be more peaceful than a multipolar world of democracies. At the same time, several studies have argued that economic cooperation among democracies is more likely to prevail when the distribution of power is asymmetric, or when one state is "hegemonic."71 While recognizing that economic conflicts among democracies may not ignite international wars, the manner in which they are resolved is still influenced if not determined by the distribution of power within the particular issue-area.72 This point leads to an observation about the state of international relations scholarship, as exemplified by the books reviewed herein. What they all share is 70. For the debate, see Lynn-Jones and Miller, The Cold War and After. 71. See, for example, Gilpin, War and Change; and Kapstein, The InsecureAlliance. 72. See Baldwin, "Power Analysis." This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Realism 773 not the assumption of rational state behavior but rather a concern about state power-how it is accumulated and how it is exercised.73 Scholars across the methodological and theoretical spectrum are reexamining the most fundamen- tal concept in politics: power. If the current theoretical crisis promotes a fresh understanding of power, to include comparisons of the ability of different types of states to extract and employ economic and military resources, it will have left a promising legacy for future generations.74 And in this exercise, contemporary scholars would do well to reexamine and then go beyond the work of such classical realists as Morgenthau, Kennan, and Kissinger, who were concerned with the material bases of power (unlike structural realists), but rather less with the nature of domestic regimes. Conclusions The books under review have led us to wonder whether a structural approach still provides a useful starting point for analyzing international politics. If systemic pressures are weak or indeterminate when it comes to foreign policy, then structural theories would seem to tell us almost nothing about how states will behave in their international interactions. This suggests that future explanations should begin within the nation-state. Why, then, can we not take the decisive step and simply abandon structural realism once and for all? Why should it remain, as Robert Keohane asserts, "a necessary component in a coherent analysis of world politics?"75 Does not such an approach mislead rather than guide us? In this review essay, I have tried to provide some reasons as to why a structural theory remains valuable for students of international relations. Beyond its continuing merits on heuristic grounds, neorealism provides a useful starting point for understanding outcomes in the international system. Further, with its emphasis on both system and unit, neorealism is perhaps the only paradigm that actually does treat domestic and international politics as a whole. But perhaps a more profound, if troubling, answer to why we still cling to neorealism was provided by Kuhn in his classic work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. He wrote: Let us then assume that crises are a necessary precondition for the emer- gence of novel theories and ask next how scientists respond to their exis73. For an optimistic view of the rationality assumption, see Duncan Snidal, "The Game Theory of International Politics," in Kenneth Oye, ed., Cooperation Under Anarchy (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986). 74. For one compelling study along these lines, see Margaret Levi, Of Rule and Revenue (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988). 75. Robert Keohane, "Theory of World Politics: Structural Realism and Beyond," in Keohane, ed., Neorealism and Its Critics, pp. 158-203. The quotation is drawn from p. 159. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 774 International Organization tence. Part of the answer ... can be discovered by noting first what scientists never do when confronted by even severe and prolonged anomalies. Though they may begin to lose faith and then to consider alternatives, they do not renounce the paradigm that has led them into crisis.... The decision to reject one paradigm is always simultaneously the decision to accept another.76 76. Kuhn, Structure of Scientific Revolutions, p. 77. This content downloaded from 94.7.218.89 on Sun, 14 Aug 2022 11:41:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms