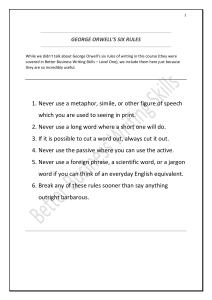

Why I write Politics and English language Shooting an elephant The hanging Summary Summary Summary Summary • • • • Orwell says at the start that he always felt he should be a writer. He attempted to "abandon" the notion in his early adult years, but he realised it was his true calling and that he would someday "settle down and write books."He claims that as a lonely child, he would make up stories and have imaginary talks, and that this loneliness may have contributed to his ambition to become a writer. Orwell's literary career began when he had two poems published in the neighbourhood newspaper during the First World War, when he was still a young boy. He continued to think like a writer in his teens, making up a "continuous "narrative" about myself," but he never recorded it. He aspired to write "enormous naturalistic novels with unhappy endings, full of detailed descriptions and arresting similes, as well as full of purple passages in which words were used partly for the sake of their sound" when he was in his twenties. Then, according to Orwell, there are four main reasons why people choose to become writers: egoism, aesthetic enthusiasm, historical impulse, and political purpose. The desire to be regarded as smart, to be talked about while still alive, and to be recalled after death is egoism. The appreciation of beauty in both the written word and the surrounding environment is referred to as aesthetic excitement. The drive to disclose the truth to readers and see things objectively is the historical motivation. The desire to alter people's perceptions of the type of society they want to live in is referred to as a political purpose. This third one is debatable because Orwell contends that every author takes a stance on a certain issue: "Once again, no book is truly free from political bias." The belief that politics and art should not interact is a political stance in and of itself. Perhaps surprisingly, given that he is best known for his "political" writing, Orwell admits that, by nature, the first three motives usually come first for him. But when the Spanish Civil War started in 1936, Orwell was clear about his position. Every line of serious writing he has produced since 1936 has been, as he famously states, "written for democratic socialism, as I understand it, and against totalitarianism." In his statement "Why I Write," George Orwell says that he has attempted to make political writing "into an art" throughout the ten years from 1936. He admits that his motivation hasn't always been altruistic, but rather has been just as self-centered and "vain" as it is in most writers, but he also understands that "one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one's own personality." Orwell's writing has improved thanks to his exposure to the political world. Ideas • education • identity • purpose • art Orwell starts off by highlighting the strong correlation between the language authors employ and the calibre of political thought in the time period under discussion (the 1940s). He contends that because language and mind are so tightly related, if we use vocabulary that is slovenly and decadent, it makes it simpler for us to fall into harmful mental habits. Then, Orwell provides five examples of poor political writing. He highlights two issues that are present in all five of the passages: stale imagery and a lack of detail. The authors of these passages either didn't care whether they successfully communicated their intended meaning or simply said things out of habit rather than because they thought they should. Current political writing suffers from the issue that it "consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated hen-house," according to Orwell. Orwell then goes into detail about the many flaws in contemporary English literature, including: dying metaphors are figures of speech that writers clumsily use even if they are outdated and no longer able to conjure up a striking image. Orwell mentions several examples include swansong, toe the line, Achilles' heel, and no axe to grind. Using terms like "toe the line" or "tow the line" incorrectly or mixing metaphors, again because they are uninterested in the feelings those images elicit, are only two examples of how Orwell feels authors should avoid using these dying metaphors. Operators, sometimes known as verbal false limbs, are used when a single-word (and more direct) verb is substituted with a lengthier, more ambiguous phrase. For example, the verb "make contact with" simply means "contact." Additionally typical are writing expressions like by examination of as opposed to the more straightforward by examining. Because the thought or idea being communicated is not particularly compelling, sentences are prevented from fizzling out by largely meaningless concluding platitudes like greatly to be desired or brought to a satisfactory conclusion. Pretentious Diction: Orwell highlights various points in this passage. According to him, authors embellish straightforward truths with terms like "objective," "basis," and "eliminate" to make subjective opinion appear to be factual information. International politics is described using words like epic, historic, and inevitable, whereas writing that exalts conflict uses words like realm, throne, and sword. To project an image of culture and elegance, foreign expressions like deus ex machina and mutatis mutandis are frequently used. In fact, many contemporary English writers use Latin or Greek vocabulary in the mistaken idea that they are "grander" than native Anglo-Saxon ones: Latinate words like expedite and alleviate are mentioned by Orwell here. Meaningless terms: According to Orwell, a lot of literary criticism and art criticism in particular are full of terms like "human," "living," and "romantic" that have no true meaning at all. In today's political writing, the word "fascism" has also lost any meaning and instead merely refers to "something undesirable." Orwell "translates" a well-known chapter from the biblical Book of Ecclesiastes into modern English, complete with its ambiguous terminology, to illustrate his argument. He contends that "the whole tendency of modern prose is away from concreteness." In contrast to his own madeup interpretation of this text, he draws attention to the concrete and commonplace images (such as references to bread and wealth) in the Bible narrative. Orwell claims that the issue is that it is easier—and more tempting—to use these stock terms in speech and writing than it is to be more clear, creative, and accurate. Orwell concludes ‘Politics and the English Language’ with six rules for the writer to follow: Beginning with some of his early experiences as a young police officer serving in Burma, Orwell shares some of his memories. Although it has been disputed how much of the essay is autobiographical, we will refer to the narrator as Orwell himself for convenience. Like other British and European citizens of imperial Burma, he was detested by the locals, who would trip him up during games of football between the Europeans and Burmans and would shout derogatory remarks about their European colonisers in public. Orwell claims that these encounters left him with two things: they confirmed his already-formed belief that imperialism was bad and they established in him a hate of the hostility that existed between European imperialists and their native people. Of course, these two are connected, and Orwell is aware of the Buddhist priests' resentment over being subject to European power. He understands this point of view, but it's unpleasant to be the target of someone else's mockery or scorn. Between his "hatred of the empire" he served and his "rage against the evil-spirited little beasts who tried to make [his] job impossible," he finds himself torn. The major action of Orwell's narrative occurs in Moulmein, a city in Lower Burma. One of the domesticated elephants that the locals own and utilise has been causing mayhem throughout the bazaar after giving its rider, or mahout, the slip. It has demolished huts, butchered cows, and descended on fruit stands in search of sustenance. To see what he can achieve, Orwell grabs his firearm and mounts his pony. Although he is aware that the elephant won't be killed by the rifle, he nevertheless holds out hope that the elephant will be startled by the gunshot. Orwell finds out that the elephant just killed a guy by trampling him to the ground—a coolie or native labourer. Sending his pony away, Orwell orders the delivery of an elephant gun, which would be more efficient against such a large animal. When Orwell goes in search of the elephant, he discovers it calmly munching on some grass and appearing as harmless as a cow. The situation has since cooled down, but thousands of local Burmese people have gathered and are now closely observing Orwell. Even though he no longer feels the need to murder the animal. Despite the fact that it no longer constitutes a threat to anyone, he recognises that the community expects him to kill it and that failing to do so will cost him "face" both personally and as an imperial agent. He then kills the elephant from a safe distance and is amazed at how long it takes the beast to pass away. At the conclusion of the essay, he admits that the only reason he shot the elephant was to avoid appearing foolish. Ideas Ideas • society • identity 1. Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print. • power 2. Never use a long word where a short one will do. • justice 3. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out. 4. Never use the passive where you can use the active. 5. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent. 6. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous. • Ideas • education • art • biblical anecdotes One morning in Burma, an imprisoned man was hanged, according to Orwell. The jail's superintendent is eager to get rid of the inmate's hangover because the other inmates won't be able to eat breakfast until it gone. Francis, a Dravidian (a race of south Asian people found in India and neighbouring countries), is the head jailor. Francis' speech features sibilant pronunciations of words like "is" and "iss." As the prisoner is being led from his cell to the gallows, a stray dog appears and approaches the crowd of men, attempting to lick the prisoner's face. These are just a few of the minor incidents that Orwell focuses on in the lead-up to the hanging. The subsequent joyful dance, in which the prison warder and a youthful jailor try to catch the dog or chase it away, seems to pique the prisoner's lack of interest. Orwell considers that this was the first time he had thought about what it meant to execute someone in their prime of life, when they are healthy and conscious, as he follows the condemned man to the gallows. When the prisoner gets to the gallows, he repeatedly cries out to his god, shouting "Ram!" He keeps screaming while a bag is placed over his head, waiting for the command to carry out the execution. The head jailor tells a tale of a hanging where the doctor had to yank the prisoner's legs to "ensure decease" as the prisoners, including Orwell, return from the hanging. The next story he tells is of a prisoner who refused to be taken out of his cell prior to his execution, and six guards had to pull him out. The superintendent offers them all a drink of whisky after the men chuckle at his tale. They giggle as they head out to drink together. We are reminded by Orwell's final sentence that the "dead man was a hundred yards away." • society, community • power • justice • racism • identity