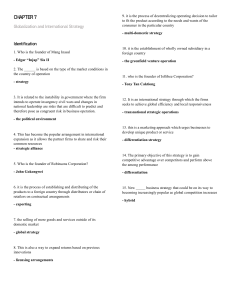

Hal G. Rainey - Understanding and Managing Public Organizations (Essential Texts for Nonprofit and Public Leadership and Management)

advertisement