Organizational Behavior 13th Edition Don Hellriegel John W. Slocum Jr.

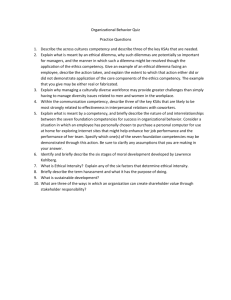

advertisement