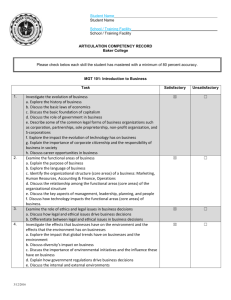

571117957-Business-and-Society-a-Strategic-Approach-to-Social-Responsibility-Ethics-Ferrell-Linda-Ferrell-O-C-Thorne-Etc-Z-lib-org-1

advertisement