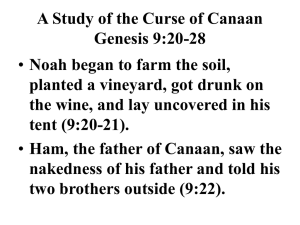

(Studies of the Bible and Its Reception 10) David M. Goldenberg - Black and Slave. The Origins and History of the Curse of Ham-Walter de Gruyter (2017)

advertisement