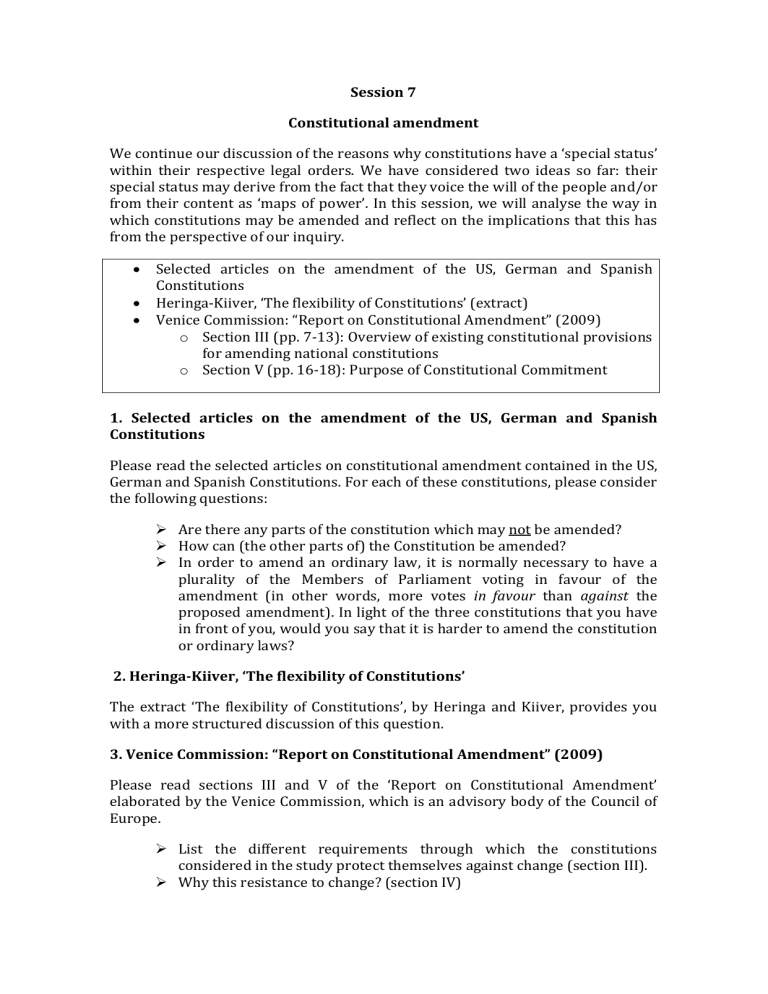

Session 7 Constitutional amendment We continue our discussion of the reasons why constitutions have a ‘special status’ within their respective legal orders. We have considered two ideas so far: their special status may derive from the fact that they voice the will of the people and/or from their content as ‘maps of power’. In this session, we will analyse the way in which constitutions may be amended and reflect on the implications that this has from the perspective of our inquiry. Selected articles on the amendment of the US, German and Spanish Constitutions Heringa-Kiiver, ‘The flexibility of Constitutions’ (extract) Venice Commission: “Report on Constitutional Amendment” (2009) o Section III (pp. 7-13): Overview of existing constitutional provisions for amending national constitutions o Section V (pp. 16-18): Purpose of Constitutional Commitment 1. Selected articles on the amendment of the US, German and Spanish Constitutions Please read the selected articles on constitutional amendment contained in the US, German and Spanish Constitutions. For each of these constitutions, please consider the following questions: Are there any parts of the constitution which may not be amended? How can (the other parts of) the Constitution be amended? In order to amend an ordinary law, it is normally necessary to have a plurality of the Members of Parliament voting in favour of the amendment (in other words, more votes in favour than against the proposed amendment). In light of the three constitutions that you have in front of you, would you say that it is harder to amend the constitution or ordinary laws? 2. Heringa-Kiiver, ‘The flexibility of Constitutions’ The extract ‘The flexibility of Constitutions’, by Heringa and Kiiver, provides you with a more structured discussion of this question. 3. Venice Commission: “Report on Constitutional Amendment” (2009) Please read sections III and V of the ‘Report on Constitutional Amendment’ elaborated by the Venice Commission, which is an advisory body of the Council of Europe. List the different requirements through which the constitutions considered in the study protect themselves against change (section III). Why this resistance to change? (section IV) Selected articles on the amendment of the US, German and Spanish Constitutions US Constitution (1789) Article V The Congress, whenever two thirds of both houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose amendments to this Constitution, or, on the application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several states, shall call a convention for proposing amendments, which, in either case, shall be valid to all intents and purposes, as part of this Constitution, when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the several states, or by conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Congress; provided that no amendment which may be made prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any manner affect the first and fourth clauses in the ninth section of the first article; and that no state, without its consent, shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate. German Grundgesetz (1949) Article 79 (1) This Constitution can be amended only by statutes which expressly amend or supplement the text thereof. (…) (2) Any such statute requires the consent of two thirds of the members of the Bundestag and two thirds of the votes of the Bundesrat. (3) Amendments of this Constitution affecting the division of the Federation into States Lä nder, the participation on principle of the Lä nder in legislation, or the basic principles laid down in Articles 1 and 20 are inadmissible. Constitution of Spain (1978) PART X. Constitutional amendment Article 166 The right to propose a Constitutional amendment shall be exercised under the terms contained in clauses 1 and 2 of Article 87 [which means that the power to initiate the procedure of Constitutional amendment lies with the Government, the Congress, the Senate and the legislative assemblies of the Autonomous Communities]. Article 167 1. Bills on Constitutional amendment must be approved by a majority of three-fifths of the members of each House. If there is no agreement between the Houses, an effort to reach it shall be made by setting up a Joint Commission of Deputies and Senators which shall submit a text to be voted on by the Congress and the Senate. 2. If approval is not obtained by means of the procedure outlined in the foregoing clause, and provided that the text has been passed by an absolute majority of the members of the Senate, Congress may pass the amendment by a two-thirds vote in favour. 3. Once the amendment has been passed by the Cortes Generales, it shall be submitted to ratification by referendum, if so requested by one tenth of the members of either House within fifteen days after its passage. Article 168 1. If a total revision of the Constitution is proposed, or a partial revision thereof, affecting the Preliminary Title, Chapter Two, Section 1 of Title I, or Title II, the principle shall be approved by a two-thirds majority of the members of each House, and the Cortes shall immediately be dissolved. 2. The Houses elected must ratify the decision and proceed to examine the new Constitutional text, which must be approved by a two-thirds majority of the members of both Houses. 3. Once the amendment has been passed by the Cortes Generales, it shall be submitted to ratification by referendum. Article 169 The process of Constitutional amendment may not be initiated in time of war or when any of the states outlined in Article 116 are in operation. ‘The Flexibility of Constitutions’ – extract from AW Heringa and P Kiiver, Constitutions Compared. An Introduction to Comparative Constitutional Law (2nd edn; Antwerp: Intersentia, 2009) A state that has adopted a single charter as its constitution in the narrow sense, codifying most of its broader constitution in that document, typically gives that document a special status. Among other things, that special status is reflected in the fact that in order to change that document, a special procedure has to be followed. Special procedures then differ from the normal legislative process by which statutes, or acts of parliament, are adopted. Sometimes certain important elements in the constitution cannot even be changed at all. Constitutions that are harder to change than ordinary legislation are called 'rigid constitutions' or 'entrenched constitutions'. There, it is made more difficult to change the rules of the game, as it were, than to play the game itself. Typical amendment procedures for rigid or entrenched constitutions include the requirement for super-majorities in parliament (e.g. Germany, Portugal); two parliamentary readings of the amendment and new elections in between readings (e.g. the Netherlands, Sweden); ratification of the amendment in the state's component territorial sub-units (e.g. United States, India in certain cases) or a referendum (e.g. Australia, France usually). Some constitutions are more rigid than others. The German Basic Law is harder to amend than ordinary statutes are, because both legislative chambers have to adopt an amendment with a higher-than-usual majority. Nevertheless, the text was amended that way about fifty times during its first fifty years of operation. The US Constitution, by contrast, has in its first two hundred years of existence seen only twenty-seven amendments, the first ten of which were included as a block right at the beginning. Yet then again, a constitutional amendment in the US requires, once the proposal is adopted, the approval of three-quarters of all the individual States. For fifty States that means thirty-eight approvals, something that is not necessary for amendments in Germany, and that may explain the endurance of the original text in the US. At the same time, the German Basic Law excludes some of its fundamental features from future amendment: humanrights principles and its federal character, for example, may not be changed. The French Constitution does not allow any change to the republican character of its government. The US Constitution has no such 'forever clause', and is formally less rigid in that respect. Rigidity may thus refer to both the procedure and the scope of a possible amendment: the former makes change relatively difficult to accomplish, the latter limits the subjects that can be changed in the first place. The opposite of hard-to-amend rigid constitutions are 'flexible constitutions'. The constitution of the United Kingdom, since it is not contained in a central document, does not prescribe any special amendment procedures. Therefore, it can be changed in the course of an ordinary legislative process, or as a result of the emergence of new customs or case-Iaw in practice. (…)