Examples of transcultural processes in two colonial linguistic documents

advertisement

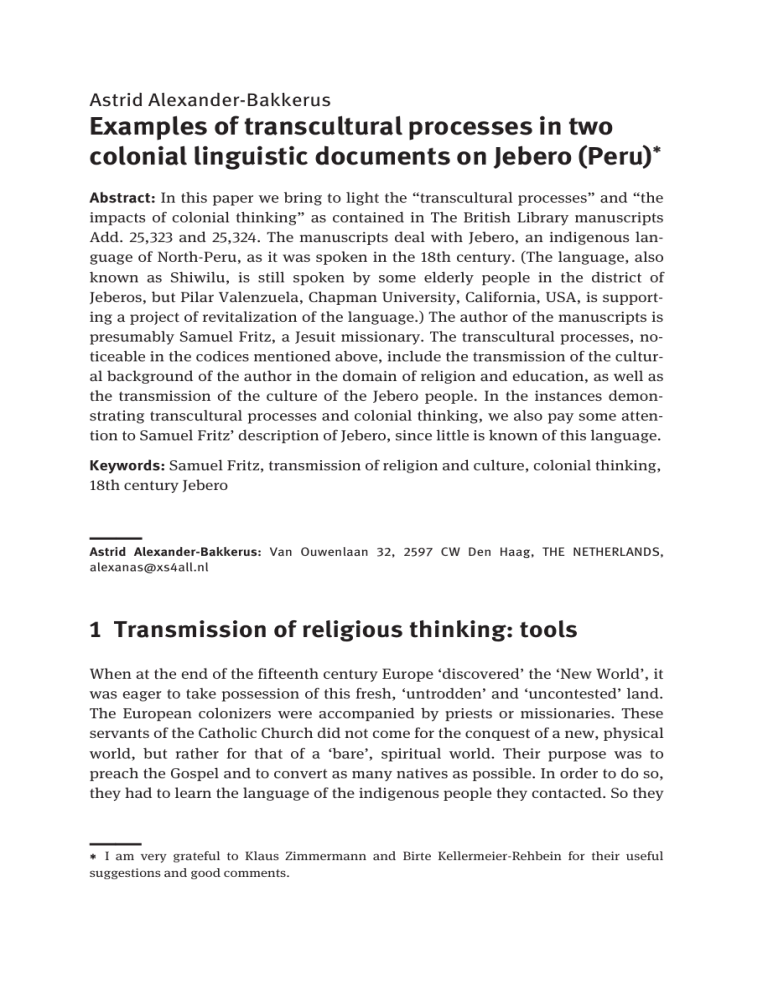

Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus Examples of transcultural processes in two colonial linguistic documents on Jebero (Peru) Abstract: In this paper we bring to light the “transcultural processes” and “the impacts of colonial thinking” as contained in The British Library manuscripts Add. 25,323 and 25,324. The manuscripts deal with Jebero, an indigenous language of North-Peru, as it was spoken in the 18th century. (The language, also known as Shiwilu, is still spoken by some elderly people in the district of Jeberos, but Pilar Valenzuela, Chapman University, California, USA, is supporting a project of revitalization of the language.) The author of the manuscripts is presumably Samuel Fritz, a Jesuit missionary. The transcultural processes, noticeable in the codices mentioned above, include the transmission of the cultural background of the author in the domain of religion and education, as well as the transmission of the culture of the Jebero people. In the instances demonstrating transcultural processes and colonial thinking, we also pay some attention to Samuel Fritz’ description of Jebero, since little is known of this language. Keywords: Samuel Fritz, transmission of religion and culture, colonial thinking, 18th century Jebero || Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus: Van Ouwenlaan 32, 2597 CW Den Haag, THE NETHERLANDS, alexanas@xs4all.nl 1 Transmission of religious thinking: tools When at the end of the fifteenth century Europe ‘discovered’ the ‘New World’, it was eager to take possession of this fresh, ‘untrodden’ and ‘uncontested’ land. The European colonizers were accompanied by priests or missionaries. These servants of the Catholic Church did not come for the conquest of a new, physical world, but rather for that of a ‘bare’, spiritual world. Their purpose was to preach the Gospel and to convert as many natives as possible. In order to do so, they had to learn the language of the indigenous people they contacted. So they || I am very grateful to Klaus Zimmermann and Birte Kellermeier-Rehbein for their useful suggestions and good comments. 232 | Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus threw themselves into the writing of vocabularies and grammars of the languages at issue, which then became “un instrumento de la evangelización” ‘an instrument of evangelization’ (see Zimmermann 1997: 15). This is certainly the case regarding the manuscripts Additional 25,323 and 25,324 from the British Library. They date from the 18th century. Both manuscripts have not been published yet, but a diplomatic edition is in preparation. The former, Vocabulario dela lengua Castillana, la del Ynga, y Xebera, is a trilingual Spanish-Quechua-Jebero dictionary. The latter contains parts of a Doctrina Christiana ‘Christian doctrine’ in Quechua and Jebero, and a Jebero grammar: Gramatica dela Lengua Xebera (henceforth GLX). The presumable author of the writings is Samuel Fritz (1654–1728), a Jesuit missionary, born in Bohemia, were German was widely spoken among the ruling classes and became increasingly dominant. This explains why the author refers to German words when explaining Jebero sounds, which do not occur in Spanish and which he could not represent by means of a letter of the Spanish alphabet, but which do occur in German. The author wrote the manuscripts for his fellow “Missioneros” ‘missionaries’ in order to propagate “la palabra de Dios” ‘the word of God’ (Ms. Add. 25,323, fol. 2v). 1.1 A Christian doctrine The conveyance of the Catholic faith, which Samuel Fritz made his aim when he composed his writings, comes clearly to the fore in the Ms. Add. 25,234. The codex opens with a Christian doctrine, which fills the greatest part of the manuscript and runs up to 35 pages: fol. 1r-18r. (The GLX tails the codex with 22 pages: fol. 19r-29v.) The first folio of the Christian doctrine is a loose part of the original doctrine. It begins with the following warning: Dios pileŋtul-a-ka-su lalá Santa Yglesia lala-neŋ-unda God command-SN-1s-SN word Holy Church word-3sPOS-COR nu-ilala-su sökdep’ð-a-meŋ tiyeg-e-tiyun-ti be-FREQ-SN comply.with-SN-2s be.saved-EU-2sFUT-ASS ‘You will be saved, if you always comply with the commandments of God and the Holy Church’. This warning finger is followed by the Act of Contrition, fol. 2r, in which the prayer, a sinner, is remorseful for having offended God and he fears that he will go to hell. The Christian doctrine itself begins at page 4, fol. 2v. It contains, amongst other things, Examples of transcultural processes | 233 (i) (ii) a short catechism for every day (fol. 2v-4v); questions concerning the sacraments of baptism and penitence, including the articles of faith, fidelity, hope, and charity (fol. 5r-6v); (iii) a short confession (fol. 6v); (iv) an interrogation about sins which everybody, men, women, married people, can commit (7r-10r); (v) the last rites (fol. 10r-11v); (vi) the sacrament of matrimony (fol. 12r-v). The contents of this part of the doctrine, fol. 1r-12v, can be considered as instructions for fellow missionaries and successors. Remarkably is the fact that the first part of the doctrine concerns a bilingual doctrine in which Quechua is the source language. Remarkably, because in the Spanish colonies the missionaries usually used Spanish doctrines, translated into the indigenous language at issue. In such bilingual doctrines Spanish thus functions as the source language and the indigenous language as the object language. It is likely that the author used Quechua as the source language, since Quechua was the lingua franca and most of the population had at least a passive knowledge of the language. Many priests also already knew Quechua when they were sent to the inland to preach the Gospel. The author himself states that he worked together with ladinos, Spanish-Indian half-breeds, and with bilingual Quechua-Jebero speakers. He also takes for granted that a future user of his manuscripts knows Quechua, or, as he says: “sepa el sentido delas palabras dela lengua general”1, i.e. Quechua. More surprisingly, in the last part of the doctrine, it is Jebero that functions as the source language and Quechua as the object language. In this part, the missionary probably changed his tactics by using Jebero as the source language to make sure that his message was understood by everybody, also by those who only spoke Jebero. He obviously also chose a Jebero speaker with knowledge of Quechua (and, possibly, of Spanish) to assist him to secure that the teachings of the church came through clearly. The Jebero-Quechua part of the Christian doctrine contains the following prayers (fol. 13r-14r): (i) Pater Noster ‘Our Father’; (ii) Ave Maria, ‘Hail Mary’; (iii) Credo ‘Creed’; (iv) Salve [Regina] ‘Hail Holy Queen’. || 1 [knows the meaning of the words of the general language] 234 | Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus The prayers are preceded by the Trinitarian formula, the sign of the cross, and they are followed by the commandments of God and the Church, a list of the sacraments, and a full confession (fol. 15r-18r). Fol. 14v contains an advice of the author. On this page, Samuel Fritz addresses himself directly to his successors, insisting that they should explain repeatedly, i.e. cada domingo ‘every Sunday’, to the autochthonous lo que rezan, lo que niegan, lo que creen, loque han de hazer ò de dexar2, so that they do not pray como papageyo.3 This pastoral advice partly shows the way the Catholic faith was transmitted, sc. by urging the people to attend Mass every Sunday and by repeating the Catholic duties and prayers over and over again, so that the priestly message was implanted and the Jeberos could become ‘good’ Catholics.4 1.2 A grammar Most of the colonial grammars or artes were written by priests. They needed a grammar in order to understand the language of the people they wanted to Christianize, so that they could communicate their message and translate their religious texts into the language in question. It comes to no surprise that, in those grammars, the priest often referred to parts of Bible verses, prayers, liturgical texts and the confession, to clarify certain linguistic structures and phenomena. In the GLX we can find many of such examples. For instance, to show that in Jebero prepositional concepts, such as ‘for/instead of’, ‘from/in’, ‘from/ of’, ‘in(side)/‘within’, ‘to’, and ‘with’, are expressed by case marking suffixes or suffix combinations, the author gives the following examples: ‘for’, expressed by the benefactive marker -maleg: (1) saserdote Dios-maleg xuča demuweto-li priest God-BEN sin forgive-3s ‘The priest forgives [our] sins for God’. || 2 [what they are praying, what they are negating, what they are believing, what they have to do or to refrain from] 3 [like a perrot] 4 A more sophisticated strategy to transfer the Catholic faith is demonstrated by Zimmermann (2014) in his analysis of the Sahagun’s Colloquius y Doctrina christiana. Zimmermann says that, in the Nahuatl version, references to ‘Aztec religious phenomena’ are in Nahuatl, whereas references to ‘peculiarities of the Christian-Catholic faith’ are in Spanish, and that “the inclusion of Spanish terms in the Náhuatl discourse [...] had the purpose of avoiding undesired and heretic interpretations”. Examples of transcultural processes | 235 ‘from/in’, expressed by the locative-delative combination -keg-la: (2) Santa Maria du-neŋ-keg-la Jesu Christo oklinando-li Saint Mary womb-3sPOS-LOC-DEL Jesus Christ be.born-3s ‘Jesus Christ was born of the womb of Saint Mary’. (3) Dios ayu-lek ledenot-a-keg-la God offend-1s think-SN-LOC-DEL ‘I have offended God in thoughts’ (4) kwap’r-losa-keg-la mointin-la woman-PL-LOC-DEL exceed-2s ‘You exceed amongst the women’. ‘from/ of’, expressed by the genitive marker -ki(n): (5) supay-ki ma-losa-neŋ luwir-la-nda devil-GEN thing-PL-3sPOS turn.away-2s-QM ‘Do you turn away from devilish things?’ ‘in(side)’, ‘within’, expressed by the inessive marker -lala: (6) iglesia-lala-kek church-IN-LOC ‘from inside the church’ ‘to’, ‘with’, expressed by the comitative marker -lek(n): (7) muča-apa-lek not-inilad virgin Santa Maria-lekn pray-DUR-1s be-FREQ virgin Saint Mary-COM ‘I am praying to the everlasting virgin Saint Mary’. (8) sad-a-ø-su-lekn-ata xuča noto-si-k’n marry-SN-3s-SN-COM-QM sin do-SN-2s ‘Have you committed adultery?’ (lit. ‘Have you committed sins with a married woman?’) Examples with a religious tenor in which other affixes occur, such as the discourse markers -ti ‘assertion’, -unda ‘coordination’, ata/-nda, a question marker; the adjectival/adverbial suffixes -imbo ‘negation’, -nunda ‘repetition’, -čaka/-saka ‘restriction’; and the plural markers -(dap’ð)-losa, indicating a nominal plurality, and misan, a collective marker, meaning ‘all do’, are the following: -ata/ -nda ‘question marker’: (9) má-ata Dios (x) thing-QM God ‘What is God?’ deŋ-ata Dios 2sPRON-QM God ‘Are you God?’ 236 | Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus (-nda occurs after the second person singular marker -la, see (vi) above, -ata elsewhere); -čaka/-saka ‘restrictive marker’ (-čaka is used after [s] in final position, -saka elsewhere): (10) Dios-čaka God-RSTR ‘God only’ -(dap’ð)losa ‘plural’: (11) kalowe-að-ka-su-dap’ðlosa hell-PL-1s-ST-PL ‘hells’ -imbo ‘negation’: (13) missa lao-keð Mass attend-2sIMP ‘Attend the Mass!’ (15) (12) xuča-wan-losa sin-POSS-PL ‘sinners’ (14) xuča-wan-imbo-su sin-POSS-NEG-ST ‘someone without sins’ missa lao-imbo-pa-tiŋ Dios ayu-la Mass hear-NEG-DUR-2s God ennoy-2s You offend God by not attending the Mass’ -misan ‘collective marker’: (16) malea-misan-ku pray-COL-2pIMP ‘Pray, all of you!’ -nunda ‘repetition’: (17) nambi-nunda-li mosninanlo-kek pa-li be.born-RE-3s heaven-LOC go-3s ‘He resuscitated [and] ascended into heaven’ -ti ‘assertative marker’ (cf. the assertative marker -mi in Quechua): (18) malea-tik-ti (19) missa laok-tik-ti pray-1sFUT-ASS Mass hear-1sFUT-ASS ‘I shall pray, yes’ ‘I shall attend Mass, yes’ (20) Dios ni-lin-ti God be-3s-ASS ‘God is, yes’ -unda ‘coordinator’: (21) domingo-losa-kek fiesta-losa-kek-unda Sunday-PL-LOC feast-PL-LOC-COR ‘on Sundays and feasts’ Examples of transcultural processes | 237 Note that the coordinator unda meaning ‘and’, ‘also’, ‘although’, is the only conjunction in Jebero, and that in complex sentences the conjunction may be omitted: (22) saserdote-losa-saka nana Dios iñanto-li enka-li priest-PL-RSTR this God can-3s give-3s nana lala-ke xuča demuwet-a-ø-su this word-COM sin cover-SN-3s-SN ‘God gave the power of absolution to priests only’ 1.3 A vocabulary Colonial vocabularies could also be used for the transmission of religious thinking. This thinking manifests itself in the sorts of entries and semantic fields occurring in the vocabulary, sc. entries and semantic fields concerning catholic concepts. In the Vocabulario dela lengua Castillana, la del Ynga, y Xebera instances of catholic concepts are encountered in different semantic fields, such as, in: (a) the semantic field of priestly duties: absolve anula- ‘leave’ demote- ‘cover’ atiyeg- ‘liberate’ ask for alms Dios-maleg lakGod-BEN ask ‘to ask in the name of God’ baptise; bless a-linlin-wan CAUS-name-VB ‘to give a name’ (deliver) a sermon Dios lala-neŋ God word-3sPOS ‘God’s word’ give the extreme unction iyade-kek bika-ti-k’n grease-INS rub-1sFUT-2sO ‘I shall rub you with grease’ preach Dios lala-neŋ wentuGod word-3sPOS advise ‘to advise God’s word’ ring the bell repika- < Sp. Repicar 238 | Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus (b) prescriptions for the convert: (give) alms limosna < Sp. limosna confess konfesa- < Sp. confesar (have) a good conscience linlin-wan-a-ø-su kanga name-VB-SN-3s-SN heart ‘a Christian heart’ (lit. ‘a baptised heart’) fast lathe day of fasting la ugli marry nana-lekn in-ventu-li, in-ma-a him/her-COM REFL-offer-3s REFL-take-2pD t-a-meŋ say-SN-3sPOS lit. ‘He/She offers himself/herself to him/her, saying: “We both take each other”. (do) penitence penitensiya < Sp. penitencia (c) a field of ecclesiastical affairs: candle kandela < Sp. candela cross kolosek’ð disciple ninitit-a-ø-su understand-SN-3s-SN ‘he is being understanding’ eternal glory nu-ilala-su sakeg-losa be-FREQ-SN feast-PL ‘feasts that are always being’ faith latog-a-ka-su believ-SN-1s-SN ‘my belief’, ‘my faith’ Father (priest) patili < Sp. Padre the grace of God Dios katopa-li God help-3S ‘God helps’ miracle milagro < Sp. milagro the procession starts prosesiyon iyunsu-tiyu procession get.out-3sFUT ‘the procession will get out’ tomb timi-pi lála die-PST.PRT hole ‘hole of a deceased’ Examples of transcultural processes | 239 The translations of the words mentioned above show that the autochthons were unfamiliar with these concepts, so that that they did not have a right equivalent for them in their own language, as a result of which these concepts could not be translated directly into Jebero. Thus, the concepts were either translated by a borrowing from Spanish (cf. milagro ‘miracle’ from Sp. milagro), by a periphrasis (cf. timipi lala, meaning ‘a hole in which a corps can be/is buried’ for ‘tomb’), or by a word which in a certain context can have the same meaning (cf. the verbs anula- ‘leave’, demote- ‘cover’, and atiyeg- ‘liberate’ for ‘absolve’). The fact that both ‘baptize’ and ‘bless’, expressing two different practices, are referred to by the same word in Jebero, also gives evidence that the Jeberos were unknown with these practices and that they did not know what ‘baptise’ and ‘bless’ actually imply. From their point of view both acts were executed by a priest with holy water, so that they termed both alilinwan- ‘to give a name’. It shows that, 1) the Jebero people did not make a distinction between a sacrament and a ritual; 2) they did not realize that by baptism the person to be baptized may call himself a Christian and becomes a member of the Catholic church; 3) they did not understand that objects can be blessed, but not be baptised. It furthermore shows that the attempts of the Catholic missionary to transmit his ideology and practices by means of a translation into the indigenous language had not always the desired effects. The enumeration of the Jebero translations mentioned in (a), (b) and (c) above is just a selection of the corpus. Translations occurring supra in section 2.1, such as malea- ‘pray’ (xvii), (xix), mosninanlo ‘heaven’ (xviii) and virgen ‘virgin’ (vii), for instance, have not been listed. 2 Transmission of a Western culture Since Samuel Fritz, the presumable author of the manuscripts, had been educated in Europe, where Latin was the language of the church and of the humanities, it is inevitable that this cultural background is reflected in the grammar which he conjecturally wrote. His linguistic cultural luggage comes to light in the way the author described the indigenous language, viz. “in terms of a Latin model” (Smith-Stark 2007: 4). In the GLX, the author distinguishes, for instance, five Latin cases (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, and ablative), and he chooses the word tana ‘mountain’ as an example. However, all the ‘declined’ 240 | Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus tana-forms are the same, with the exception of the accusative form tana-kek, which he translates as ‘to the mountain’. The suffix ­ke(k/g) or -ki(k) is actually a multi-functional morpheme. It can function as a locative ‘at’ or an inessive ‘in’, a genitive or separative ‘from’, a directive ‘to’ (see the example tana-kek ‘to the mountain’ above), and as an instrumental ‘with’: (23) nanaŋ-kek there-LOC ‘at/in the mountain’ (24) deŋ-kek who-GEN/SEP ‘whose’, ‘from whom’ (25) Quito-keg-la Quito-SEP-DEL ‘from Quito’ (26) yomotu-kek axe-INS ‘with an axe’ The verb is treated likewise. The author conjugates a Jebero verb as is customary in Latin. He ascribes tenses, moods, and nominalized forms to the Jebero verb, which the verb does not have, and his verbal paradigm is an image of a Latin paradigm. For instance, the conjugation of the verb wentu- ‘advise’ contains the following Latin tenses, moods, and nominalized forms: present, imperfect, future, imperative, prohibitive, subjunctive/optative, infinitive, 2 gerunds (dative and ablative), and participles. In reality, there is no distinction between the present tense and the imperfect; prohibitive has only a few forms, constructed with the negations aneð and uya; subjunctive and optative are nominalized forms, overlapping the other nominalized forms, such as the gerunds and the participles.5 A transmission of the cultural baggage of the author is especially noticeable in the vocabulary. The words referring to his culture are countless. They are translated by means of a borrowing, a periphrasis, or a word meaning metaphorically or in certain contexts more or less the same, cf. those with a religious purpose in section 1.2. The words reflecting a Western culture concern, amongst other things, the names of animals and plants, iron tools and other objects, furniture, numbers, periods of time, products, and relatives. All these unknown items and concepts came along with the colonizers and were subsequently introduced into the indigenous community. The following word list is a choice from the multitude of items found in the vocabulary referring to the European background of the author: || 5 According to Klaus Zimmermann (p. c.) the language description in terms of a Latin model is ‘a colonial device’: “It is a strategy to communicate to other missionaries who knew the Latin grammar. It was not a descriptive error, but a communicational strategy in a colonial context. He did not write the grammar for the Jebero people, but for the missionaries.” Examples of transcultural processes | 241 bastard bed color cow report flour godfather granddaughter hammer key permission law lemon margarine marry needle be obliged oil rope servant soap spoon stepmother teach ten wall week window nað wawa biti-ka-gek sleep-1s-LOC kolor waka wentharina compa nieto martiyo lyawi licencia pileŋdu-la-ka-su lala command-2sA-1sO-SN word limon wira ya-in-ma-li DES-REC-take-3s lawa obligasion pani-li obligation have-3s aceite sodotek wila muda-neŋ jabon kučara auba pot-a-ø-su mother be.as-SN-3s-SN a-nintuCAUS-understand kat-ótekgla-du two-hand-QNT lupa semana wentana ‘that/other child’ ‘my sleeping place’ < Sp. color < Sp. vaca ‘advise’ < Sp. harina < Sp. compadre < Sp. nieto < Sp. martillo < Sp. llave < Sp. licencia lit. ‘the word of your commanding me’ < Sp. limón ‘grease’ ‘they want to take each other’ ‘thorn’ < Sp. obligación ‘obligation’ ‘he has obligations’ < Sp. aceite < Sp. soga ‘Indian’ ‘his/her Indian’ < Sp. jabón < Sp. cuchara ‘she is like a mother’ ‘cause to understand’ ‘two hands’ ‘clay’ < Sp. semana < Sp. ventana The periphrastic translations ‘that/other child’ and ‘they want to take each other’ for the concepts ‘bastard’ and ‘marry’, respectively, give evidence that in Jebero men and women just lived together and had children, and that practices 242 | Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus like marriage and the legitimization of a child were needless, since the passing down of land, titles or goods, which in the Western Christian society is regulated by marriage and legitimization, were obviously not applicable in a Jebero community. Those practices were introduced under colonial administration. A number of nouns and verbs referring to a Western culture were adopted through Quechua, the lingua franca in Peru, such as: bread read ribbon write tanda kilyka drawing čúmbeð kilyka drawing nintituunderstand notomake < Q t’anta < Q qelyqa- ‘to draw’ > ‘to write’ ‘understand drawings’ < Q čumbi ‘make drawings’ The colonizers/missionaries also introduced numbers from Quechua into Jebero: hundred ten thousand pasak čunga waranga < Q pačak < Q čunka < Q waranqa The original Jebero counting system had four numbers: ala katu kala enkatu one two three four For the designation of numbers higher than four, the Jebero used hands and fingers: five six seven eight nine ala ötegla-du one hand-QNT ‘one hand’ intimutu ‘thumb’ tanituna ‘index’ tanituna kabi-a-ø-su index be.next-SN-3s-SN ‘the one which is next to the index’ (lit. ‘him being next to the index’) biti-n ötegla kabi-a-ø-su sleep-3sPOS hand be.next-SN-3s-SN ‘the one which sleeps next to the hand’ (lit. ‘his sleeping being next to the hand) Examples of transcultural processes | 243 ten kat-ötegla-du four-hand-QNT ‘two hands’ 3 Transmission of ‘colonial thinking’ Besides examples of cultural transmission, we can also find reflections of superseded colonial thinking in the dictionaries and artes of the missionaries. This colonial thinking manifests itself in the paternal attitude of the lexicographer or the grammarian towards the Amerindians and the language which he has to translate or describe, especially when he runs up against difficulties concerning the translation of a word and the description of a sound or a structure. For Samuel Fritz, being a child of his time, who was brought up in Europe, colonial thoughts were his own. Manifestations of Eurocentric thinking are encountered in the comments added to the lexicographic, grammatical and religious texts. At the beginning of the vocabulary, for instance, the author warns that the Indians badly pronounce their own language (!) and that they are not intelligible, since, (i) “muchas letras confunden”6, i.e. sounds; (ii) “pronuncian las vocales como diftongos”;7 (iii) “la mayor dificultad tiene la pronunciacion dela d, pues la pronuncian [...] como media r, media l, y algunas vezes como media h”;8 (iv) “la n muchas vezes apenas pronuncian”;9 (v) “tambien à su querer añaden al fin de la sylaba ti sin que se muda la significacion, ni enlos verbos, ni enlos nombres […]. Otras vezes tambien usan en lugar de particulas preguntativas”.10 The author states that his unintelligibility and that what he categorizes from his Eurocentric and scriptural-centric point of view as his confusion of sounds is due to the fact that the Indians do not have books and that they cannot write || 6 [they confuse many “letters”] 7 [they pronounce vowels as diphthongs] 8 [they do not know how to articulate the sound [d], because it is partly articulated as [r], as [l], and sometimes as [h]] 9 [the nasal [n] is hardly pronounced] 10 [and all the time they add the syllable ti to nouns and verbs without changing their meaning. They also use it [the syllable ti] as a substitute for question markers] 244 | Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus “por falta delibros y ortografia”. He also complains that the Jeberos do not speak Quechua, and that “especialmente porlas mugere[s], de las quales parece que no aya esperanza de que aprend[en] la lengua del Ynga [...] y asi quedaran p[ri]vadas del pasto espiritual necessario”.11 At the end of the Christian doctrine, the author addresses himself to his successors and he urges them to explain every Sunday to the Indians “lo que rezan, lo que niegan, lo que creen, lo que han de hazer ò dexar”12, so that they do not speak “como papageyo”13 [...]” (see also section 1.1). From this Eurocentric observation we may conclude that the missionary sees his flock as a featherbrained group of men and women, who cannot think by themselves and who are just echoing what somebody else tells them to say. The author thus ignores that the Indians can very well understand the message and the intentions of the missionaries, and that they are familiar with religious thinking. Like any other culture, the Jeberos had its shamans or priests and its spirits or gods to whom they prayed. The indigenous culture also had its do’s and don’ts which the people had to observe, such as the three basic, time-honored Quechua commandments: ama llullakuy-chu ‘do not lie’, ama suway-chu ‘do not steal’, ama wañuchiy-chu ‘do not kill’. Manifestations of a colonial range of ideas are also encountered in the word list itself. For instance, the words muda, meaning ‘man’, ‘heart’ in Jebero, and wila ‘child’, are used to translate the Spanish word criado ‘servant’. The word muda is also employed for the translation of the word indio ‘Indian’, so that ‘Indian’ becomes synonymous with ‘servant’, and ‘Indian’ equals ‘servant’ (cf. muda-neŋ ‘his Indian’). At the same time, the Spanish words señor and señora, meaning ‘gentleman/master’ and ‘madam/mistress’, respectively, are introduced into the lexicon of the Jebero people. The terms muda ‘Indian’, ‘servant’, indicating a Jebero man, and señor ‘master’, ‘sir’ and señora ‘mistress’, ‘madam’, indicating a Spanish man and woman, respectively, clearly reflect the introduction of a new, colonial system of social relationships between the Spaniards and the Jebero people, and the distinction in status between both groups. || 11 [especially for the women, there seems to be no hope that they will ever learn the Quechua language [...], so that they are devoid of the indispensable pastoral guidance] 12 [what they are praying, what they are negating, what they are believing, what they have to do or to give up] 13 [as perrots] Examples of transcultural processes | 245 4 Transmission of the indigenous culture The cultural transmission is not unilateral. It also occurs the other way round, not compellingly, but under the skin. When the missionaries tried to translate European and catholic concepts into an indigenous language, they had to search for an equivalent in the object language; and when they tried to describe the complex structure of an Amerindian language by means of the Latin model they were faced with difficulties. Through this searching of equivalents and facing with difficulties they came in contact with a completely different world, and thus became aware of a totally different range of thoughts, which they had to bear in mind in order to be able to deliver an adequate translation and a right description of the language in question for their fellow missionaries. 4.1 Linguistic phenomena Notwithstanding the fact that the author of the GLX describes the Jebero language on the Latin model, he is aware of the fact that the language is structured differently. He perceives, for instance, that personal reference markers occur as suffixes attached to nominal and verbal stems in Jebero (see the translation of the number ‘nine’ in section 2), and that the category of prefixes is missing, but that the language has ‘postpositions’ instead, i.e. all sorts of suffixes that have a prepositional meaning when attached to noun, and that function as case markers, see the examples with the suffixes -maleg ‘for/instead of’, -keg-la ‘from/in’, -ki(n) ‘from/of’, -lala ‘in(side)/‘within’, -lekn ‘to’, ‘with’, in section 1.2, and -kek ‘at’, ‘from’, ‘in’, ‘to’, ‘with’, in section 2. The grammarian also perceives that modalities and aspects which in a language like German and English are indicated by a modal or by an adverb are marked by a prefix in Jebero: ya-pa-lek DES-go-1s ‘I want to go’ ap’ð-li-na steal-3s-IT ‘he always steals’ With respect to the verb, the author furthermore notes that the verb has two tenses: a present tense and a future tense. He subsequently exemplifies his present tense by means of the following forms: wentu-lek wentu-li ‘I advise’, ‘I advised’ ‘he advises’, ‘he advised’, ‘it is advised’ 246 | Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus The forms show that what the author calls a ‘present tense’ includes an imperfective aspect, rather than a present tense, a perfective aspect, and a passive voice. Since the author considers this tense to be a counterpart of the future tense, the term ‘non-future’ tense would be a better appellation to refer to the so-called present tense. As regards the future tense, the grammarian remarks that it has irregular forms and that it has a first person dual: regular: kalo-tik ‘I shall cook’ < kalo- ‘(to) cook’ irregular: noteð-tik first person dual: kalo-a ‘the two of us will cook’ noto-a ‘the two of us will do/make ‘I shall do/make’ < noto- ‘(to) do/make’ Note that the first person dual is regularly formed, and that a first person inclusive is constructed with the plural marker -wa: kalo-a-wa ‘we all will cook’, noto-a-wa ‘we all will do/ make’. 4.2 Lexical items The different world and the exotic cultures the colonizers became acquainted with when they entered the Americas, are clearly represented in their dictionaries. There we can find Spanish periphrases describing Amerindian animals, plants, clothes, etc. A number of these items, for which the Spaniards did not have an equivalent, were adopted as loan words, cf. ‘jaguar’ < Guaraní yawar-ete (dog-real ‘the real dog’), ‘tomato’ < Nahuatl (Aztec) toma-tl, ‘poncho’ < Q punču. In the trilingual Spanish-Quechua-Jebero vocabulary, a great number of entries refer to the living conditions of the Jebero people. Many of these concepts concern the flora and fauna of the Jebero habitat and its surroundings. Since these items do not have a Spanish equivalent, they are often translated by means of a periphrasis, a borrowing from Quechua, or a surrogate concept. Items referring to the indigenous flora are often followed by the words fruta ‘fruit’ to emphasise that the item at issue is a fruit: Q sapalla, fruta ku ‘avocado’ batata, Q kumar, fruta aču ‘sweet potato’ cascabel, fruta sangamupi ‘small bell’ (cascabel means ‘small bell’ and ‘rattlesnake’ in Spanish. The fruit indicated as such possibly resembles a bell.) Examples of transcultural processes | 247 fruta como granos, miedo por esso las chagiras dizen ‘miedó’ Q ungurawi, fruta señala ‘fruit like grain’ therefore the farmers call it ‘miedó’ ‘a kind of tuber’ The name of a tree is also often followed by the designation arbol ‘tree’ to indicate that it concerns a tree: balsamo, arbol Q wito, arbol estoraque, el arbol čunalatek öksá söt-teala balsa, el arbol sapote, arbol subuna táku Q sitika, arbol mankóna ‘balm’ ‘kind of fig’ ‘storax’ (used for its balsam and resin) ‘balsa tree’ ‘sapota’ (produces edible fruits and Shea butter) ‘mustard tree’ Names of animals also occur numerously in the vocabulary. They are occasionally followed by the designation animal ‘animal’. The names of fishes, on the other hand, are often indicated as such and followed by the specification pexe (pez or pescado in modern Spanish) ‘fish’: Q maxas, animal Q mota, pexe palmeta, pexe Q woki chico, pexe Q sungaro, pexe dökana kačameð ðog wang’ðtik ‘paca’ (kind of rodent) ‘kind of catfish’ ‘kind of fish’ ‘kind of small fish’ (chico means ‘small’) dawansamerð ‘kind of big fish’ Interestingly, the lexicographer also distinguishes different sorts of animals of the same kind. It gives evidence of how annoying insects can be and of his lively interest in the indigenous fauna, especially in monkeys: flies: snakes: turtles: mosca que entra en los ojos rodador culebra mediana chiquita verde charapa grande mediana pequeña yiyu dawerla isekpila dawa tandeŋmowa siwa asinluntowalek puka, ítu mapápa dameðöta ‘fly’ ‘fly that enters the eyes’ ‘fly that keeps flying around’ ‘snake’ ‘medium-sized snake’ ‘small snake’ ‘green snake’ ‘big kind of edible turtle’ ‘medium-sized turtle’ ‘small turtle’ 248 | Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus monkeys: mono ardilla ‘clever’ blanc[o] negro felines: guapo ‘beautiful’ leon, puma, tigre tigrillo, zorro tigrillo de noche duda solo lolo béa avena, marti óltiu châuben tíqueglóna mudáni anas, nini wasála ‘white-bellied monkey’ ‘wooly monkey’ ‘kind of howling monkey’ ‘clever kind of monkey’ ‘white monkey’ ‘black monkey’ ‘capuchin monkey’ ‘beautiful kind of monkey’ ‘puma’ ‘fox’ ‘nocturnal kind of fox’ A few other interesting types of naming animals are: buytre nocturno pútek ‘nocturnal vulture’ Q hatun tuta piscu ‘big nocturnal bird’ (the Quechua description of the animal gives evidence that it concerns another kind of bird rather than a vulture. A kind of owl maybe?) langosta verde ingueðla ‘green lobster’ venado, taruga boró ‘deer’ The following entries are related to the living conditions of the Jebero people, such as how they fish, hunt, make music, embellish and cloth themselves, what they drink and which illnesses they may catch: fishing and hunting: feasting: clothing : canoa lanza flecha harpon veneno barbasco achiote bebida de yucca de maiz de platanos de chonta flauta Q anaco nau pán-ni námu ukwana, yulo kapálek punanli, porapalek lowa wasu uglólo tötöyek dangúdök oðapidök pileðña kalakasu manta de yndios kapi ‘canoe’ ‘spear’ ‘arrow’ ‘harpoon’ ‘poison’ ‘kind of poison’ ‘red painting’ ‘drink’ ‘yucca drink’ ‘corn liquor’ ‘banana drink’ ‘kind of palm drink’ ‘flute’ ‘Indian wraparound skirt’ ‘Indian blanket’ Examples of transcultural processes | 249 deseases: Q kusma ahuala kapi pampanilla calentura kalanándek čukču < Q čukču de frios lepra sarna l’kulkoto-lek asi sala ‘kind of shirt’, ‘small blanket’ ‘small head cloth’ ‘malaria’, ‘quartan fever’ ‘I have a quartan fever’ ‘leprosy’ ‘scabies’ 5 Conclusion: colonial-ideological strategies of transculturation14 and their impact When the Europeans, following the tracks of their explorers, colonized South America, they brought their culture with them, which they subsequently imposed on the Amerindian population. For the transmission of their standards and values, including their religion, the colonizing countries could also rely upon the powerful Roman Catholic Church, which soon sent its representatives and its missionaries to the newly ‘discovered’ territories. Through their works the missionaries transmitted not only the Catholic faith, but also their European background, as we have seen, so that their writings became not only the mouthpiece of the church and a tool of evangelization and, but also a tool of transculturalization and a mouthpiece of the colonizing country at issue. The Christian doctrine, for example, the tool of evangelization par excellence, imposes not only what to believe, but also how to believe, and it enforces a number of rules of life, such as the obligation to attend Mass every Sunday, to confess, to fast, to marry, to serve the church, and the ban on killing, committing adultery, stealing, lying, being jealous, etc. The impact of these do’s and don’ts was considerable. They completely changed the social structure and the way of life of the indigenous people who were leading a free, somewhat nomadic existence in the woods. (For their living they gathered wild fruits, honey and cotton, they fished, hunted and traded at will or out of necessity, and cultivated some crops.) The church, whether or not with the aid of the army, gathered || 14 For appealing examples of transculturation and a typology of transcultural processes see Zimmermann (2006). He defines the act of transculturalization as “el intento de entender algo ajeno en terminus de algo propio” ‘the intention to comprehend something exotic or peculiar in terms of something proper’, and in (Zimmermann 2009: 168) as: “la integración de elementos de una cultura en otra” ‘the integration of elements of a culture in another one’. 250 | Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus groups of different tribes into reducciones or conversiones: villages with a church, build and maintained by the indigenous population, where the inhabitants led a Christian lifestyle under the command of a priest, who was also maintained by the natives. The authority of the priest was undeniable. The example saserdote Dios-maleg xuča demuweto-li ‘The priest forgives our sins for God’ in section 2.1, gives evidence that the clergyman construes himself as a person with the power of forgiving, and that, by this, he establishes himself as an authoritarian person in the native community. He could also administer justice and inflict a punishment.15 The housing of indigenous groups in reducciones, where their life was regulated according to Christian standards, was useful, not only to the church, but also, from a political viewpoint, to the government: natives roaming in the jungle could not be controlled, whereas native groups living in a village supervised by a priest could be governed easily. Another colonial strategy to impose the Western culture and the Catholic faith and herewith to control the indigenous people was the strategy of ‘translingualization’, i.e. the use of Spanish words in Amerindian texts, or “the general term for any influence of one language onto another” (Zimmermann 2014). In his article about Sahagún’s the translation of Aztec texts, Zimmermann also argues that “the objective of translating the [...] religious sermons from the Aztec religion, was not to mexicanize the Spanish, i.e. bringing them closer to the Aztec religion [...] (Zimmermann 2014: 97). It was rather a step in the endeavor to evangelize the Mexicans and control their spirits”, because ‘through language imposition’, ‘through the transfer of terms from one language to another’, the religious thinking of the user could be controlled. Examples of the use of Spanish loan words in the Jebero discourse can be found not only in the Christian doctrine, but also in grammar, where they are integrated in the morphological and morphosyntactical structure of Jebero, as if they are an integrant part of the language. If we assume that language is a reflection of the way we think and see the world around us, the Spanish loan words, integrated in the Jebero discourse and Jebero-like structured, thus seem to be part of the thinking and the vision of the world of the Jebero. The vocabularies were also strategies of transmission of colonial-cultural values, besides being a tool of religious transmission. The dictionaries were not normative or regulative, they rather gave a “representación mental del mundo” || 15 Cf. for instance the following phrase in Cholón, another North Peruvian language (Alexander-Bakkerus 2005: 276): mitah-la-č či-po-šayč-aŋ 3sO.miss-3pA-FAC 3pA-3pO-whip-IA ‘They whip them because they missed it [the Mass]’ Examples of transcultural processes | 251 ‘mental representation of the world’ (Zimmermann 2006: 320). In the SpanishQuechua-Jebero vocabulary, for instance, we can clearly distinguish lemmas transmitting a Western culture and colonial viewpoints, see the word list ‘bastard – window’ in section 2, from those referring to the Jebero way of life, see the items in section 4.2. A number of those items are translated by means of an explicative periphrasis, reflecting a colonial perspective, such as: bebida buytre calenture cascabel charapa culebra fruta langosta manta mono mosca tigrillo de chonta oðapidök de yucca uglólo de maiz tötöyek de platanos dangúdök nocturno pútek Q hatun tuta piscu de frios čukču < Q čukču fruta sangamupi grande puka, ítu mediana mapápa pequeña dameðöta chiquita siwa mediana tandeŋmowa verde asinluntowalek como granos, por miedo esso las chagiras dizen ‘miedó’ verde ingueðla de yndios kapi ardilla ‘clever’ béa guapo ‘beautiful’ tíqueglóna blanc[o] avena, marti negro óltiu que entra en los ojos dawerla de noche wasála ‘kind of palm drink’ ‘yucca drink’ ‘corn liquor’ ‘banana drink’ ‘nocturnal vulture’ ‘big nocturnal bird’ ‘malaria’, ‘quartan fever’ ‘small bell’ ‘big kind of edible turtle’ ‘medium-sized turtle’ ‘small turtle’ ‘small snake’ ‘medium-sized snake’ ‘green snake’ ‘fruit like grain’ therefore the farmers call it ‘miedó’ ‘green lobster’ ‘Indian blanket’ ‘clever kind of monkey’ ‘beautiful kind of monkey’ ‘white monkey’ ‘black monkey’ ‘fly that enters the eyes’ ‘nocturnal kind of fox’ In conclusion we can say that by means of religious writings, such as Christian doctrines, grammars or artes, and dictionaries, the colonizing countries tried to impose their religion and their standards on the Amerindian society. An attempt which was not always fruitful. On the other hand, the examples in section 4.1 and 4.2 show that the author of both manuscripts, notwithstanding the fact that he had a religious end in mind when he wrote them, certainly had an eye for the particular construction of the Jebero language and its special phenomena, for 252 | Astrid Alexander-Bakkerus the way the Jebero speak and see the world, and, last but not least, for the world in which they live. Abbreviations and symbols A Add. ASS BEN CAUS COL COM COR DEL DES DU DUR EU FAC fol. FREQ FUT GEN GLX IA IMP IN INS IT LOC Ms. NEG agent additional assertative marker benefactive causative collective comitative coordinator delative desiderative dual durative euphonic element factitive folio frequentative future genitive Gramatic dela Lengua Xebera imperfective aspect imperative inessive instrumental iterative locative manuscript negation O p PL POS POSS PRON PST.PRT Q QM QNT r RE REC REFL RSTR s SEP SN Sp. ST v VB 1 2 3 < > object plural plural marker possessive possession marker pronoun past participle Quechua question marker quantifier recto repetition reciprocal reflexive restrictive singular separative stative nominalizer Spanish state marker verso verbalizer first person (subject) second person (subject) third person (subject) derived from resulting in Examples of transcultural processes | 253 References Alexander-Bakkerus, Astrid. 2005. Eighteenth-century Cholón. Utrecht: LOT. Anonymous (18th century). Vocabulario enla Lengua Castellana, la del Ynga, y Xebera. Ms. Add. 25,232, British Library. Anonymous (18th century). Doctrina Christiana and Gramatica dela Lengua Xebera, Ms. Add. 25,324, British Library. Smith-Stark, Thomas C. 2007. Lexicography in New Spain (1492–1611). In Otto Zwartjes, Ramón Arzápalo Marín & Thomas C. Smith-Clark (eds.), Missionary linguistics IV, lexicography, 3–82. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins. Zimmermann, Klaus. 1997. Introducción. Apuntes para la historia de la lingüística de las lenguas amerindias. In Klaus Zimmermann (ed.), La descripción de las lenguas amerindias en la época colonial, 9–17. Frankfurt am Main & Madrid: Vervuert/Iberoamericana. Zimmermann, Klaus. 2006. Las gramáticas y vocabularios misioneros: entre la conquista y la construcción transcultural de la lengua del otro. In Pilar Máynez & María Rosario Dosal G. (eds.), V. encuentro Internacional Lingüística en Acátlan, 319–356. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Méxio. Zimmermann, Klaus. 2009. La construcción discursiva del léxico en la Lingüística Misionera: interculturalidad y glotocentrismo en diccionarios náhuatl y hñahñu-otomí de los siglos XVI y XVII (Alonso de Molina, Alonso Urbano y autor anónimo 1640). Revista Internacional de Lingüística Iberoamericana 7(1). 161–186. Zimmermann, Klaus. 2014. Translation for colonization and Christianization: The practice of bilingual edition of Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590). In Klaus Zimmermann, Otto Zwartjes & Martina Schrader-Kniffki (eds.), Missionary linguistics V/ Lingüística V: Translation theories and practices. Selected papers from the Seventh International Conference on Missionary Linguistics, Bremen, 28 February – 2 March 2012 (Studies in the History of Language Sciences 122), 85–112. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.