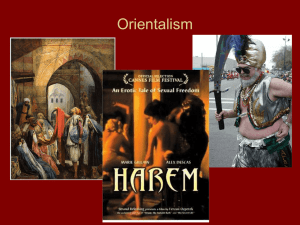

1 Nicole Mikly Bernal The phenomenon of Orientalism Edward Said (1935, Jerusalem -2003, New York, United States) was a political activist and professor from Columbia University, specialized in literary critic and postcolonial studies. He received the Prince of Asturias of the Concord prize in 2002 with Daniel Barendoim for founding the West-East Divan Orchestra. His most important publications are Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography (1966), The Politics of Dispossession (1994), After the Last Sky (1986), and Orientalism (1978).1 This paper will focus on Edward Said’s understanding of Orientalism as it is described in his book. First, we will describe what the Orient is, secondly, we will define Orientalism, and last, we will present a conclusion which summarizes the analysis of the text. For the purposes of his investigation Said limits the Orient geographically to what is usually refer as “The Middle East” or “The Near East”, this means that he leaves out some parts of the East such as India, Japan, China and basically all the territories known as the “Far East” -not because these regions lake of importance, but because it is possible to study the experience that Europe had in the Middle East and in the Islamic countries regardless of their experience in the Far East-. Nevertheless, according to Said, Orient is not an inert fact of nature, and neither the Occident. They are both historical entities or geographical man-made sectors with a history, a tradition of thought, an imagery and a specific vocabulary to which they are referred. The two geographical entities support and reflect each other, the Orient has helped define the Occident as a contrasting image. The “Orient was almost a European invention, and had been since antiquity a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences.” 2 But this image is not equivalent, the relationship between the Occident and the Orient is determined by domination in varying degrees of complex hegemony. 3 This domination expressed itself in establishment of some of the oldest European colonial governments. The Orient also became a career for Westerners: Orientalism studies. To understand the meaning of Orientalism in a general way, Said proposes that it is a style of thought based on an ontological and epistemological distinction between the ‘Orient’ and the ‘Occident’. 4 The most readily accepted definition, is that it is a scientific specialty restricted to a geographical "field". In Said’s words, the historical origins of Orientalism began with the decision of the Church Council of Vienne in 1312 “to establish a series of chairs in "Arabic, Greek, Hebrew, and Syriac at Paris, Oxford, Bologna, 1 Encyclopedia of World Biography. Edward W. Said Biography (Consulted on February 15, 2019) https://www.notablebiographies.com/supp/Supplement-Mi-So/Said-Edward-W.html 2 Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books Edition, 1979), 1 3 Concept coined by Gramsci “In any society not totalitarian, then. certain cultural forms predominate over others, just as certain ideas are more influential than others; the form of this cultural leadership is what Gramsci has identified as hegemony, an indispensable concept for any understanding of cultural life in the industrial West.” (Said, 1979, 7) 4 Said, Orientalism, 2 2 Avignon, and Salamanca."5 Furthermore, Silvestre de Sacy (1757- 1838) was the pioneer of the orientalism, he translated the bulletins of Grande Armée and Napoleon’s Manifesto of 1806 with which Napoleon was hoping to use to said the Muslims against the orthodox Russians. Later, Sacy took part of the Tableau Historique writing team, who canonized the Orient by using orientalist knowledge and a ‘power’ vocabulary. Sacy was treating East as a reality that had to be restored, because of it disorderly presence, so the Orientalist have to reinvent the Orient. The continuity of this study was personified by Renán, who consolidated the official speech, systematized the institutions and represented the cultural and intellectual practice by means of the philologic laboratory. 6 The outcome of this intellectual and historical process was the objectification of the Orient as a thing that could only be understood through the eyes of the orientalist. In Saids words: “Truth, in short, becomes a function of learned judgment, not of the material itself, which in time seems to owe even its existence to the Orientalist.”7 These ideas of the intellectual orientalist became the filter by which Westerns understood the East and it was them who decided who was Oriental based on Western’s desires, interests and projections. The academic discovery, the anthropological descriptions and the psychological analysis helped support the idea of controlling those who are different. At the same time, this is a discourse that produces itself under an unequal exchange determined by various powers: “power political (as with a colonial or imperial establishment), power intelectual (as with reigning sciences like comparative linguistics or anatomy, or any of the modern policy sciences), power cultural (as with orthodoxies and canons of taste texts, values), power moral (as with Ideas about what "we" do and what "they" cannot do or understand as "we" do.”8 Therefore, one can say that Orientalism is a sign of the European power over the East. It is an ideological discourse that authorizes declarations on the East, established canons of taste, value and rests on a vocabulary of erudition, a few doctrines and colonial styles. Orientalism is based on the externality of the West over the East, the Orientalists are outside of the Orient existentially as morally, because of this reason the generated representations of the Orient are distant, amorphous and oversimplified. Orientalism moves away from East itself and depends more on the West, on its own ideological and hegemonic pretensions. This idea of the representation of other one becomes theatrical where “the Orient is the stage on which the whole East is confined. On this stage will appear figures whose role it is to represent the larger whole from which they emanate. [...] The Orient [is a] closed field, a theatrical stage affixed to Europe.”9 The representations realized on the East, are depending on an erudite 5 Ibíd., 49,50 Ibíd., 122 7 Ibíd., 67 8 Ibíd., 12 9 Ibíd., 63 6 3 judgment, an imagined geography that spreads across portraits as the bible or the Bibliothéque Orientale of D'Herbelot, and not precisely on the materiality of the East itself. Geography and the imagined history help to intensify the distance and the difference between the nearby thing and the otherness. Now then, for Said, from a philosophical point of view, Orientalism is an external form of realism. From a rhetorical point of view, it is anatomical and numbered, and when used in a particular vocabulary, is divided and particularized in Eastern realities. From a psychological point of view, Orientalism is a form of paranoia, not the same type we know of ordinarily. 10 Said studies the coherence between the east as a career and the real East. In addition, he analysed Orientalism as a dynamic exchange between individual authors and the political worries of the empires (British, French and American) where it took place. These relations can be understood better if “we realize that their internal constraints upon writers and thinkers were productive, not unilaterally inhibiting.”11 Said saw a possibility inside these own limitations and he proposed to study them from two methodological resources: the strategic location and the strategic formation. 12 The nexus of knowledge and power creates an idea of “Orientals” which eliminate them as human beings. Intellectuals perpetuated structures of the Orientalism with their disciplines, for that reason the academic knowledge about India and Egypt is tinged and impressed by the political factor. Said, Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler argue that “The very ideas “India” and “Africa” were homogenizing and essentializing devices useful for imperial definitions of what it was they ruled.” 13 They continue to mention that the relation between knowledge and power: “while the disciplines of geography and anthropology helped to make the expanding world intelligible and manageable, the relationship of disciplinary knowledge and colonial rule was an ambiguous one. Geography brought the same conceit of science to domestic state building as to overseas ventures.” 14 Said proposes that humanistic investigation should establish a relationship between the specific context of his study, the topic and its historical circumstances. Said also mentions that for the readers of countries of the Third world, this study is a step to the understand cultural Western speech, “my hope is to illustrate the formidable structure of cultural domination and, specifically for formerly colonized peoples, the dangers and temptations of employing this structure upon themselves or upon others.” 15 In summary, Edward Said criticized modern knowledge and imperialism by means of the concept ‘Orientalism’ which is analysed as a discourse of power. The discourse not only creates and limits what we can know, it is also a social and historical product. In other words, the discourse is both 10 Ibíd., 72 Ibíd., 14 12 “Strategic location, which is a way of describing the author's position in a text with regard to the Oriental material he writes about, and strategic formation, which is a way of analyzing the relationship between texts and the way in which groups of texts, types of texts, even textual genres, acquire mass, density, and referential power among themselves and thereafter in the culture at large.” (Said, 1979, 20) 13 Frederick Cooper, Ann Laura Stoler, Tensions of Empire(California: University of California Press, 1993), 11 14 Cooper, Stoler, Tensions of Empire, 14 15 Said, Orientalism, 25 11 4 produced and producer. But Said seems to confuse the process (the practices) with the product (the representation), as Bruno Latour mention “the moderns confused products with processes. They believed that the production of bureaucratic rationalization presupposed rational bureaucrats; that the production of universal science depended on universal scientist; they the production of effective technologies led to effectiveness of engineers; that the production of the abstraction was itself abstract; that the production of formalism was itself formal.” 16 Said seems to give more attention to the representations and forgets that these are also productions. He seems to forget that Orientalism is a product of a practice, the practice of colonial power and its material structures. Orientalism is a conceptual tool that Said uses to explain a universal phenomenon, but his reflection turns into an asymmetric valuation of the discourse and the practice, giving priority to the social sciences on the form of representation of others and turning the Western discourse into a transverse and transcendent discourse. That is to say, that Orientalism cannot only be understood in the domain of social sciences that talk about the cultures of others, or the networks of social knowledge that the universities produce, because this focus on Orientalism turns the material world into symbols of the discursive domination, and leaves aside the material structure of this domination. Finally, is there a way to overcome Orientalism? Maybe if like Said´s mentioned, Orientalism is discursive, then it is a translation problem, but if Orientalism is a power and material difference, this difference is not merely in the discourse and cannot simply be eliminated by revealing the structure of ideological discourse. Bibliography Cooper, Frederick and Stoler, Ann Laura. 1993. Tensions of Empire. California: University of California Press. Latour, Bruno. 1993. We have never been modern. United States: Harvard University Press. Said, Edward. 1979. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books Edition. 16 Bruno Latour, We have never been modern (United States: Harvard University Press, 1993), 115,116