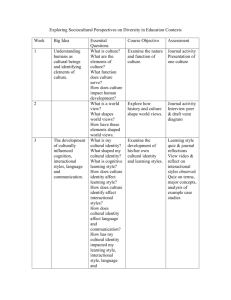

Investing in Interactional Justice: A Study of the Fair Process Effect within a Hospitality Failure Context

advertisement

Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research http://jht.sagepub.com/ Investing in Interactional Justice: A Study of the Fair Process Effect within a Hospitality Failure Context Thérèse A. Collie, Beverley Sparks and Graham Bradley Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2000 24: 448 DOI: 10.1177/109634800002400403 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jht.sagepub.com/content/24/4/448 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: International Council on Hotel, Restaurant, and Institutional Education Additional services and information for Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jht.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jht.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://jht.sagepub.com/content/24/4/448.refs.html >> Version of Record - Nov 1, 2000 What is This? Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 JOURNAL Collie et al.OF / INTERACTIONAL HOSPITALITY & TOURISM JUSTICE RESEARCH INVESTING IN INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE: A STUDY OF THE FAIR PROCESS EFFECT WITHIN A HOSPITALITY FAILURE CONTEXT Thérèse A. Collie Beverley Sparks Graham Bradley Griffith University, Gold Coast Past research has demonstrated that considerations of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice independently influence customers’ fairness and satisfaction ratings in many contexts. Other research shows evidence of a “fair process” effect—a tendency for customers to be more accepting of poor outcomes when they perceive the outcome allocation process to be fair. Van den Bos, Lind, Vermunt, and Wilke (1997) have reported that this effect may operate only when the outcomes received by others are unknown. Set in a hospitality service recovery context, this study examined the impact of interactional justice and knowledge of others’ outcomes on customers’ service evaluations. A 2 (interactional justice) 4 (others’ outcomes) experimental design was employed in which 176 respondents reported their perceptions of fairness and levels of satisfaction after imagining themselves to be customers in a hypothetical service scenario. Contrary to previous research, evidence of the fair process effect was found irrespective of the presence or absence of information regarding others’ outcomes. Implications for the tourism and hospitality industry and justice theory development are discussed. KEYWORDS: justice theory; fairness perceptions; customer satisfaction; service recovery. One of the authors recently had the following experience: While attending an overseas conference held at an island resort hotel, the author made a short (3-minute) phone call to her husband. On checking out of the hotel the following day, the author discovered she had been charged $68 for the call. She drew this apparent overcharging to the attention of the hotel clerk, and subsequently to the clerk’s supervisor, who politely agreed that the amount was excessive and immediately reduced the cost of the phone call to $37—a 45% reduction! (Point A) Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, Vol. 24, No. 4, November 2000, 448-472 © 2000 International Council on Hotel, Restaurant and Institutional Education 448 Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 449 Later that day, while waiting in line in the local airport departure lounge, the author struck up a conversation with a fellow traveler who happened to be returning home after attending the same conference at the same hotel. The author related her story of the discounted phone charge. Her colleague responded that the same thing had happened to her, and she had received a 75% reduction in the price of her phone bill. (Point B) Seeing the author’s reaction, she hastily added, “But, listen to this: I know of another delegate who was required to pay the full amount, despite lodging a similar protest!” (Point C) How would you feel as the customer at Points A, B, and C in the above story? Would you think the hotel staff had treated you fairly? Would you be satisfied with the service provided? Would you return to this hotel on subsequent visits to the island? And, more central to the theme of the present article, would your answers have been any different if, instead of the polite treatment you received, the hotel staff had spoken to you in a discourteous and dismissive manner? Justice is one of the most important concepts receiving attention in the social and organizational psychology literature (Bazerman, 1993; Cropanzano & Greenberg, 1997). It is important that the application of justice theory to service settings such as in the tourism and hospitality industry is also an emerging research domain (see, e.g., Blodgett, Hill, & Tax, 1997; Bowen, Gilliland, & Folger, 1999; Hocutt, Chakraborty, & Mowen, 1997; Sparks & McColl-Kennedy, 2000). Indeed, the theoretical frameworks underpinning justice research offer extensive opportunities for better understanding hospitality encounters, especially service failures. This article draws on theory and research into justice to learn more about the ways in which customers evaluate their experiences of service failure. To achieve this, we explore hospitality customers’ satisfaction and fairness judgments when they either do or do not have information about the sort of compensation other customers have received in similar situations. In addition, we examine the extent to which the nature of the interaction between customer and service provider affects customer reactions when varying amounts and types of information are available. Thus, we seek to demonstrate the usefulness and importance of interactional justice in recovering service failures within a hospitality setting. Service Failures and Recovery The hospitality industry exhibits many of the classic service characteristics (e.g., intangible product, simultaneous production and consumption) that make 100% zero-defect service delivery virtually impossible. Following a failure in the delivery of a service, organizations frequently attempt to retrieve the situation by identifying and responding to customer needs and expectations (Bell & Zemke, 1987). More formally, this process of service recovery has been defined in terms of tactics aimed at “returning aggrieved customers to a state of satisfaction with the organization after a service . . . has failed to live up to expectations” (Zemke & Bell, 1990, p. 43). Service recovery is important because there is evidence to suggest that when a service delivery system fails, customers’ satisfaction or dissatisfaction levels and their word-of-mouth and return intentions are dependent on the Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 450 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH content or form of the employee response (Bitner, Booms, & Tetreault, 1990; Blodgett & Granbois, 1992). If these efforts do not meet customers’ needs and expectations, the resultant dissatisfaction may have serious long-term negative consequences for the service organization (Boshoff, 1999; Tax & Brown, 1998). In contrast, appropriate recovery responses to service failures can create satisfied and loyal customers (Brown, Cowles, & Tuten, 1996). Devising a sound understanding of the efficacy of alternative service recovery tactics is vital to the industry. One potentially productive approach to increasing our understanding of customer evaluations and intentions following service failure comes from the body of theory and research into justice. Justice Theory and Research Justice, as treated by social and organizational scientists, is defined phenomenologically; an act is considered “just” because someone perceives it as such (Bazerman, 1993; Cropanzano & Greenberg, 1997; Folger & Cropanzano, 1998; Leventhal, 1980; Seiders & Berry, 1998). Contemporary theories of justice date back more than 30 years. Early theorizing focused on distributive justice (Homans, 1961); that is, people’s perceptions of the fairness of the outcomes they receive or resource distribution decisions (e.g., Adams, 1963).1 A second wave of justice inquiry, heralded by the seminal work of Thibaut and Walker (1975), demonstrated that an individual’s response to the allocation of resources was also influenced by the fairness of the allocation process, or procedural justice (e.g., Korsgaard, Schweiger, & Sapienza, 1995). In short, distributive justice concerns the fairness of ends, and procedural justice emphasizes the means used to achieve those ends (Greenberg, 1987, 1990). More recently, researchers have described types of unjust treatments that can not be easily subsumed under the traditional concepts of procedural or distributive justice (e.g., Lind & Lissak, 1985; Mikula, 1986). Many (e.g., Blodgett et al., 1997; Clemmer & Schneider, 1996; Tax, Brown, & Chandrashekaran, 1998), but by no means all (see, e.g., Greenberg, 1990), contemporary justice theorists recognize the existence of a third dimension of justice. Most notably, Bies and his colleagues (e.g., Bies, 1987; Bies & Moag, 1986; Bies & Shapiro, 1987; Folger & Bies, 1989; Tyler & Bies, 1990) argued that fairness concerns regarding how a decision maker behaves during the enactment of procedures denotes people’s concern for interactional justice. This interactional (or social) form of justice relates to the informal and dynamic aspects of outcome allocation procedures and particularly refers to those aspects of an exchange that concern communication processes and the treatment of individuals (e.g., courtesy, respect, explanations) (Cropanzano & Greenberg, 1997). By contrast, the term procedural justice is now frequently used to refer to the perceived fairness of the policies, procedures, and other structural criteria used by decision makers to arrive at an outcome (Blodgett et al., 1997). The motivation for researchers to study procedural and interactional justice arises from the belief that issues other than outcomes shape perceptions of fairness (Lind & Tyler, 1988). Indeed, a considerable body of research evidence demonstrates that all three of these dimensions of justice—distributive, procedural, Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 451 and interactional—independently affect fairness, satisfaction, and other evaluations (Clemmer & Schneider, 1996; Cropanzano & Greenberg, 1997; Greenberg, 1987; Lind & Tyler, 1988). Furthermore, researchers have provided intriguing evidence as to the interactive effects of the combination of these justice elements (Brockner & Wiesenfeld, 1996). Indeed, one of the most robust findings in social and organizational psychology is the “fair process effect,” whereby outcome evaluations and subsequent behavior are moderated by perceptions of process justice. Put another way, the fair process effect suggests that if people consider a procedure to be fair, they are more accepting of its consequences (Folger & Cropanzano, 1998; Kim & Mauborgne, 1997). (For a summary of studies demonstrating this effect, see Van den Bos, Lind, Vermunt, & Wilke [1997].) The implications of the operation of this effect are quite profound. If people are more willing to tolerate an unfavorable outcome if delivered in a fair manner, then organizations can control the damage caused by the implementation of tough decisions by ensuring that the decision-making process, and the ways in which these decisions are communicated, are beyond reproof. The fair process effect thus has potential applications in a diverse range of organizational contexts. These range from situations where organizations decide to restructure, downsize, or relocate, to those where customer loyalty is placed at risk by the need to withdraw previously offered services. The Ubiquity of the Fair Process Effect Given the wide-ranging implications of the fair process effect, there is a need for researchers to explore and clarify the parameters under which it operates. Indeed, recent research evidence has cast doubt on the ubiquity of the effect. In an innovative experiment, Van den Bos, Lind, and colleagues (1997) used a computer-based simulation to manipulate participants’ exposure to two kinds of information: First, the participants received varying information regarding the outcomes received by other people in similar situations (social comparison equity information), and second, they received varying information regarding the outcome allocation process (procedural justice information). Van den Bos, Lind, and colleagues predicted that the fair process effect would be found only in conditions where participants could not rely on social comparison equity information to make judgments of outcome fairness and satisfaction. Their hypothesis was supported: When the referent other person’s outcome was not known, the fair process effect was evident; that is, procedural justice information influenced the participants’ evaluations. However, when the other’s outcome was known, and irrespective of whether the other’s outcome was better, worse, or equal to the participant’s outcome, there was no evidence of a fair process effect: Ratings of outcome fairness and satisfaction did not significantly differ between conditions of fair and unfair procedures. In other words, in the presence of social comparison data, procedural justice information appeared redundant: Participants used the information about others’ outcomes to make their evaluations, rather than being influenced by information regarding the fairness of procedures. See Figure 1 for an overview of Van den Bos, Lind, and colleagues’ findings. Similarly designed Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 452 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH Figure 1 Representation Indicative of Van den Bos, Lind, Vermunt, and Wilke’s (1997) Fairness and Satisfaction Ratings additional tests of their hypothesis replicated these results (Van den Bos, Lind, et al., 1997; Van den Bos, Wilke, Lind, & Vermunt, 1998). To explain their results, Van den Bos, Lind, and colleagues (1997) argued that generally people do not have access to information about other people’s outcomes. Accordingly, people are typically compelled to rely on information that is available; namely, procedural justice data (Van den Bos, Lind, et al., 1997; Van den Bos, Wilke, et al., 1998). Thus, in most conditions, others’ outcomes are unknown, and so procedural justice data are used, in a heuristic manner, to shape impressions of overall fairness and satisfaction (Van den Bos, Lind, et al., 1997; Van den Bos, Wilke, et al., 1998). On the other hand, in those rare circumstances where information regarding the outcomes received by others is available, this information is given greater weight than procedural data in the formation of justice evaluations (Van den Bos, Lind, et al., 1997). In such situations, people place limited reliance on procedural justice information, and their outcome judgments show no evidence of the fair process effect. Van den Bos and colleagues’ evidence and arguments regarding the limitations of the fair process effect are, at first glance, quite appealing. However, there are several reasons for caution and for further pursuit of this line of research. First, Van den Bos and colleagues’ (1997, 1998) studies are limited by their use of single-item scales to measure the dependent variables. Such an approach potentially undermines the reliability, precision, and content validity of their fairness and satisfaction measures (De Vaus, 1995). Replication using well-established multiitem scales is warranted. Second, Van den Bos, Lind, and colleagues (1997) tempered their conclusions by emphasizing that there may be “some, as yet unidentified conditions” (p. 1043) where social comparison equity information is present, yet strong effects of procedures on outcome evaluations occur. Hence, there may be value in seeking to identify such conditions. Third, there is an impor- Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 453 tant limitation to the external validity of Van den Bos and colleagues’ (1997, 1998) findings. In these studies, the operationalization of process justice was exclusively structural in nature. Participants were informed either that they did or did not have input (“voice”) into the outcome allocation decision. There was no direct human contact: Participants’ opportunities for input (or lack thereof) were through a computer interface. Hence, issues of interactional justice were effectively eliminated from the experimental task. This exclusive focus on procedural justice leaves open the issue of whether Van den Bos and colleagues’ conclusions can be generalized to other contexts and forms of process justice. There is a need, therefore, for further research that operationalizes justice in interactional, rather than procedural, fairness terms. Service Provision in the Tourism and Hospitality Sector: The Role of Justice in Customer Evaluations Until recently, most of the research into justice issues was situated in workplace and legal contexts. However, the past decade has seen a growing interest in the application of justice theories to service encounters (see, e.g., Clemmer & Schneider, 1996; Sparks & McColl-Kennedy, 2000; Tax, 1993). Much of this early interest initially focused on outcome fairness rather than procedural and interactional justice. Nevertheless, like the workplace and legal contexts, all forms of justice are now seen as relevant to service settings (Clemmer & Schneider, 1996). This interest in the application of a justice framework to service industries has come about because of a recognition of the contribution the perspective can make to understanding the nature and dynamics of the service provider–customer relationship. The provision and receipt of services within the hospitality and tourism sector involves an exchange between customer and service provider. Both parties receive (and presumably assess) an outcome, and both recognize (and presumably evaluate) the existence of formal structures (e.g., hours of opening, modes of payment, queuing systems, refund policy, complaint handling procedures) that regulate the process of outcome allocation. Thus, considerations of distributive and procedural justice potentially affect customer (and staff) evaluations. At its core, however, the service encounter is social in nature; fundamentally, it involves one human being interacting with another (Czepiel, 1990; Czepiel, Solomon, Surprenant, & Gutman, 1985; Mattsson, 1994; Price, Arnould, & Tierney, 1995; Siehl, Bowen, & Pearson, 1992). Moreover, services, such as those in the tourism and hospitality industry, rely heavily on the service provider’s interpersonal skills (Nikolich & Sparks, 1995). Indeed, it is the quality of interpersonal interaction between the customer and contact employee that often influences customer evaluations of services (Bitner, Booms, & Mohr, 1994; Iacobucci, Ostrom, & Grayson, 1995; Schneider & Bowen, 1985; Schneider, Parkington, & Buxton, 1980). Support for this view is provided by Price, Arnould, and Deibler (1995), who found that failure to meet minimum standards of civility in a service encounter (i.e., a failure to meet interactive justice standards) induced negative emotional responses in customers “more than any other service provider performance factor” (p. 49). Similarly, in their recent review of the psychological literature on Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 454 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH interpersonal emotions in services, Dubé and Menon (1998) highlighted the critical role of socialization in forming consumer–provider interpersonal exchanges. Hence, feelings of satisfaction with service encounters are widely thought to be influenced by the level of service provider adherence to fair and consistent behavior patterns (Solomon, Surprenant, & Gutman, 1985). Furthermore, the failure of a service employee to adhere to norms of service behavior may have important consequences for his or her customers. Lovelock, Patterson, and Walker (1998) argue that seemingly uncaring or rude behavior toward a customer by service staff may violate the customer’s self- esteem “because the customer feels they should be treated with more respect” (p. 450). These authors argue that such poor treatment (which could be characterized as low levels of interactional justice) violates basic human needs such as fairness and a sense of self-worth and may result in customer complaints in an effort to restore self-esteem. The role of front-line service employee behavior in customer–service provider interactions is especially crucial in service recovery situations (Boshoff, 1997; Johnston, 1995; Tax, 1993; Tax & Brown, 1998). Research into service recovery has demonstrated that customers’ perceptions of interactional justice are particularly salient when service fails (Bowen et al., 1999; Sparks & McColl-Kennedy, 2000). Goodwin and Ross (1989), for instance, found that if a customer complained about a service failure, both rudeness and the style of interaction strongly influenced ratings of perceived fairness. A more recent service failure study by Tax and his colleagues (1998) also found that the most pervasive customer service expectations concerned courtesy and empathy. Likewise, an experiment by Hocutt and colleagues (1997) showed that interactional justice–oriented service recovery attempts (i.e., prompt, courteous service employees) led to higher satisfaction ratings than when interactional justice was low. These results prompted Hocutt and colleagues (1997) to suggest that in service recovery, interactional justice concerns may be more important than distributive justice issues. Similarly, Sparks and McColl-Kennedy (2000) found that in service recovery, positive demonstrations of interactional justice (such as politeness and concern) on the part of a service provider resulted in high ratings of fairness and satisfaction. There is, therefore, quite a large body of research evidence to support the belief that, contrary to Van den Bos and colleagues’ findings, considerations of interactional justice influence outcome judgments irrespective of the presence or absence of information regarding the outcomes received by other customers. Folger and Cropanzano’s (1998) Fairness Theory offers insights into possible mechanisms through which interactional justice has this pervasive (fair process) effect. This theory emphasizes the underlying cognitive mechanism of “counterfactual thinking” in the assignation of moral accountability to those responsible for the allocation of outcomes (Folger, 1993). Counterfactual is literally defined as “counter to the facts” (Roese, 1997), or thinking “what might have been” (Roese & Olson, 1997, p. 1). Thus, when evaluating the fairness of another’s actions, an individual might imagine possible alternative behaviors and assess whether any of the alternative actions would have been morally superior (Folger & Cropanzano, 1998). For example, if an individual experiences discourteous treatment (i.e., low levels of interactional justice), they might easily imagine that it Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 455 would have been feasible for the other party to have acted courteously, and that such courtesy would be more in keeping with prevailing moral precepts. According to this theory, when unfairness is perceived, an aggrieved party seeks to determine culpability for the offense (i.e., who is to blame) and the motives and intentions of the perceived offender. Moral accountability is then assigned to the offending person or agency. Folger and Cropanzano (1998) posit that interactional justice may prove to be a more important moderator of reactions to unfairness than either procedural or distributive justice, because greater ambiguity potentially exists as to the moral accountability of both procedural structures and tangible outcomes. On the other hand, because of the immediacy and transparency of social interactions, it may be relatively easier to assign moral accountability when interactional justice principles are violated (Folger & Cropanzano, 1998). To extrapolate somewhat, customers participating in a service encounter are likely to be in direct and immediate receipt of interactional justice information, and are more likely to use this information to assign moral accountability than to use other more ambiguous distributive and procedural justice information. There is, however, little empirical evidence directly supporting Fairness Theory, and even less supporting the speculative extrapolations of the theory proposed here. Aims and Hypothesis In summary, it is widely accepted that perceptions of a fair process influence outcome evaluations. Van den Bos and colleagues (1997, 1998) have reported evidence and proposed arguments indicating that this effect does not hold when information regarding others’ outcomes is available. However, both of Van den Bos and colleagues’ studies were limited in several ways. Specifically, these researchers operationalized process justice in exclusively structural terms, performed their tests in an impersonal context, and used single-item dependent measures. Both past research into the service encounter and Fairness Theory (Folger & Cropanzano, 1998) suggest that considerations of interactional justice are crucial in service recovery situations, and that these considerations will influence outcome evaluations regardless of the presence or absence of information regarding others’ outcomes. The aim of the current study was to investigate whether Van den Bos and colleagues’ (1997, 1998) results generalize to contexts where interpersonal aspects of an exchange are salient. To answer this question, we tested the impact of interactional justice and distributive social comparison equity information on evaluations of outcome fairness and satisfaction within a hospitality service recovery setting. In an adaptation of Van den Bos and colleagues’ (1997, 1998) methodology, we held constant procedural justice and the participants’ outcomes while experimentally manipulating both interactional justice (either high or low) and knowledge of others’ outcomes (either a referent other’s outcome is unknown or it is equal, better, or worse than that of the focal customer). This latter manipulation has ecological validity within the tourism and hospitality context because, although there are many occasions when customers are unaware of the outcomes received by others, there is a similar number of situations when customers have Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 456 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH the opportunity to observe (or hear about), for example, the size of another customer’s restaurant meal, the prices others paid for a package tour, or the compensation others received for delayed hotel check-ins. The story that introduced this article is a case in point. Given the limitations of Van den Bos and colleagues’ (1997, 1998) research and the evidence suggesting that interactive justice considerations are central to customer evaluations in service recovery situations, we put forward the following hypothesis: Hypothesis: Customer evaluations of fairness and satisfaction will vary significantly with the level of interactional justice, regardless of whether the outcome of others is known. A finding in support of this hypothesis would have several implications. First, such a finding would suggest that interactional justice functions differently from procedural justice when social comparison equity information is available. This would serve to strengthen the case for maintaining a theoretical and empirical distinction between these two dimensions of justice. Second, this finding would suggest that it may be premature to accept Van den Bos and colleagues’ conclusion concerning the redundancy of information regarding nondistributive forms of justice when others’ outcomes are unknown. Third, the finding would underscore the need for service organizations to implement management, selection, and training policies aimed at the maintenance and enhancement of customer evaluations of interactional justice. If, on the other hand, Van den Bos and colleagues’ finding is replicated using an interactional justice manipulation within a service recovery context, none of the above would follow. Rather, the implication would appear to be that organizations that are able to communicate social comparison equity information to their customers will achieve little further advantage in investing in the promotion of interactional justice. METHOD Design A 2 (interactional justice [IJ]: high or low) × 4 (others’ outcomes [OO]: unknown, better, worse, equal) independent groups factorial experimental research design was utilized. Four dependent variables (DVs) were measured: (a) outcome fairness, (b) satisfaction, (c) word-of-mouth (WOM) intention, and (d) return intention. Participants A convenience sample of 176 university undergraduate students (114 women, 61 men, and 1 of unspecified gender) enrolled in a 1st-year psychology course acted as participants. The mean age of the participants was 21.1 years (SD = 4.19). Participants received course credit for participating in the experiment. The use of Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 457 students for such research can be justified on the grounds that the task was one that the respondent was likely to identify and be familiar with given the context. Materials Scenarios Experimental scenarios have proved valuable in the study of subjective reactions to procedures (Lind & Tyler, 1988) and are used extensively in both justice and services (including hospitality and tourism) research (see, e.g., Barling & Phillips, 1993; Bitner, 1990; Boshoff, 1997; Brown et al., 1996; Goodwin & Ross, 1992; Hocutt et al., 1997; Mattila, 1999). Hence, eight service recovery scenarios were specifically developed for this study through two pilot studies. The scenarios, set in a theme park restaurant, were identical except for manipulations of the two independent variables (refer to the Appendix for complete scenario text). In all scenarios, procedural justice was held constant and operationalized as the customers being given a formal opportunity to verbally state what outcome he or she would prefer and complete a written feedback card. In all versions of the scenario, the restaurant attendant’s gender and age were not revealed, the customer paid $8 for the meal, and the customer later discussed the price paid by other students for an equivalent meal. Independent Variables The four OO conditions were operationalized as (a) unknown: the customer was unaware of the cost of the other students’ meals; (b) better: the other students paid $4 each for their meals; (c) worse: the other students paid $12; and (d) equal: both the customer and other students paid $8. In the high interactional justice conditions, the service provider (the restaurant attendant) displayed courtesy, concern, and empathy toward the customer, whereas low interactional justice was operationalized as a rude service provider who displayed no concern or empathy toward the customer. Dependent Measures The DVs (outcome fairness, satisfaction, and WOM and return intentions) were measured using multi-item scales, with each item requiring a response on a 7-point continuum (1 = very unfair/dissatisfied/unlikely, 7 = very fair/satisfied/likely). A recent scenario-based experiment by Blodgett and colleagues (1997) provided the scales for three of the DVs: outcome fairness, and WOM and return intentions. The scales used by Blodgett and colleagues were considered reliable (reported alphas of .92, .87, and .91 respectively). The multi-item satisfaction scale was adapted from Oliver and Swan (1989) because this scale has been successfully utilized in other recent service fairness studies (e.g., Sparks & McColl-Kennedy, 2000; Tax et al., 1998). Additional 7-point scale items were used to check the manipulation of the independent variables and the perceived believability of the scenarios. Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 458 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH Table 1 Scale Reliabilities and Descriptive Statistics M SD Number of Items α 4.33 3.27 6.3 1.22 1.66 .7 4 12 5 .74 .97 .79 5.32 1.33 1.19 0.51 4 4 .96 .96 Scale Outcome fairness Satisfaction Believability manipulation check Interactional justice manipulation check High Low Note: All items were measured on a 7-point scale; higher values indicate more positive ratings of the dependent variable in question. Procedure Participants were randomly allocated to one of the eight experimental conditions (n = 22 per condition). A booklet containing the appropriate version of the service scenario and the series of questions measuring the DVs, as well as several items providing manipulation and believability checks, was issued to each participant. Participants were instructed to read the scenarios, imagine that the scenarios depicted had happened to them in the role of the customer, and answer the series of questions as if they were the customer. Participants completed the task in small, noninteracting groups under the supervision of the researchers. RESULTS Preliminary Analyses Because the reliability coefficient (α) for the scales used exceeded 0.7, all scales were considered reliable (De Vaus, 1995) (see Table 1). Prior to the application of the primary multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) technique, preliminary data screening was conducted (per Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black, 1995). To ensure assumptions of MANOVA were met, 12 cases were deleted. Thus, in total, 164 cases were available for the main analyses. Bivariate correlations of the four DVs showed significant correlations among all DVs. The associations between satisfaction, return intentions, and WOM scales were considered excessive (r > .85) and, in accordance with the approach adopted in past research (see, e.g., Clemmer, 1993), the scales were averaged to form a single satisfaction scale. The use of an expanded satisfaction scale that incorporates behavioral intention items is consistent with the practice adopted in previous research (see, e.g., Goodwin & Ross, 1992). Hence, all subsequent analyses were based on two DVs: (a) outcome fairness, and (b) the expanded satisfaction scale. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for these two DVs. 2 Manipulation Checks Analysis of the manipulation check variables demonstrated that independent variable manipulations (IJ and OO) and the procedural justice constant were both Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 459 Table 2 Tests of Interpersonal Procedural Justice, Others’ Outcomes, and Their Interaction IV IJ OO IJ × OO DV Outcome fairness Satisfaction Outcome fairness Satisfaction Outcome fairness Satisfaction Univariate F a 99.21 359.58a 7.05a 1.86 0.78 0.42 df Stepdown F df α 1,156 1,156 3,156 3,156 3,156 3,155 99.21*** 158.25*** 7.05*** 0.22 0.78 0.8 1,156 1,155 3,156 3,155 3,156 3,155 .025 .025 .025 .025 .025 .025 a. Significance level cannot be evaluated but would reach p < .001 in a univariate context. ***p < .001. perceived as intended by respondents. In addition, the results indicated that participants perceived the scenarios as believable (see Table 1). Main Analyses A significant multivariate effect was indicated for interactional justice, F(2, 155) = 178.73, p < .001, and for others’ outcomes, F(6, 312) = 3.43, p < .01, suggesting that there were significant differences between both IJ and OO conditions for the dependent variables measured. The multivariate IJ by OO interaction was not significant, F(6, 312) = .79, p = .58. The results suggest a strong association between IJ and the combined DVs, partial η2 = .7, and a more modest association between OO and the DVs, partial η2 = .06. Because the results of Bartlett’s test of sphericity indicated significant interrelations among the dependent variables (p < .001), the Roy-Bargmann stepdown analysis was used to assess the impact of interactional justice and others’ outcomes on each of the dependent variables (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996). Because the main theoretical thrust of the current research is justice, outcome fairness was the dependent variable initially tested, followed by the second dependent variable, satisfaction. The stepdown analysis assumption of homogeneity of regression was tested at the stringent level of α = .01 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996) and found to be satisfactory (for the satisfaction scale, F(7, 148) = 2.4, p > .01). The results of univariate and stepdown analyses are summarized in Table 2. The stepdown analyses revealed that ratings of outcome fairness made a unique contribution to differences between levels of OO, stepdown F(3, 156) = 7.05, p < .001. After the variability due to outcome fairness was entered, satisfaction did not add to the effect of OO, stepdown F(3, 155) = 0.22, p = .88). However, more central to the focus of the current study, the results of the stepdown analyses reveal a unique contribution to the prediction of differences between high IJ and low IJ participants by both outcome fairness, stepdown F(1, 156) = 99.21, p < .001, and satisfaction, stepdown F(1, 155) = 158.25, p < .001. Therefore, the testing of the hypothesis proceeded utilizing both DVs. Evaluation of the hypothesis that IJ will affect the dependent variables regardless of the level of OO required the creation of a dummy variable labeled “group.” Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 460 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH Figure 2 Group Means for Dependent Variable Outcome Fairness Thus, there were eight groups representing the experimental conditions, which enabled a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a series of four planned orthogonal contrasts to be conducted per DV. To control for Type I error, the results of each paired contrast were evaluated using Bonferroni’s correction (α = .0125). Graphical representations of the group means are presented in Figure 2 (outcome fairness) and Figure 3 (satisfaction). For the first DV, outcome fairness, Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances was not significant (p > .05), so the pooled variance estimate t tests were interpreted for the contrasts performed. The first planned contrast involved participants in the two OO unknown conditions. It showed that in keeping with previous fair process findings, mean ratings of outcome fairness were significantly higher for participants in the high IJ condition (M = 5.32) than those in the low IJ condition (M = 4.11), t(156) = 4.2, p < .001. This finding replicates that of Van den Bos, Lind, and colleagues (1997). The second contrast between OO better participants showed that for those in the high IJ condition, the mean outcome fairness rating (M = 4.43) was significantly higher than low IJ participants’ mean outcome fairness rating (M = 3.16), t(156) = 4.35, p < .001. The third planned contrast involved participants in the OO worse conditions. Again, significantly higher outcome fairness ratings were found for those in the high IJ condition (M = 5.31) than low IJ Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 461 Figure 3 Group Means for Dependent Variable Satisfaction (expanded) participants (M = 3.54), t(156) = 6.09, p < .001. Likewise, the final planned contrast concerning those in the OO equal conditions showed that high IJ (M = 5.06) participants perceived their outcomes as significantly fairer than low IJ participants (M = 3.57), t(156) = 5.3, p < .001. A similar pattern of results was observed for the second DV, satisfaction. However, because Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances was significant (p < .05), the heterogeneous variance t tests were interpreted for the contrasts performed. The first planned satisfaction contrast also showed the fair process effect, with mean ratings of satisfaction significantly higher for participants in the high IJ, OO unknown condition (M = 4.85) than for those in the low IJ, OO unknown condition (M = 2.0), t(35.96) = 11.01, p < .001. The second contrast between OO better conditions showed that high IJ participants’ mean satisfaction rating (M = 4.22) was significantly higher than low IJ participants’ mean satisfaction rating (M = 1.71), t(27.44) = 9.76, p < .001. The third planned contrast involved OO worse participants and also demonstrated significantly higher satisfaction ratings for those in the high IJ condition (M = 4.59) than low IJ participants (M = 1.9), t(29.55) = 8.75, p < .001. As was the case for all previous comparisons, the final planned satisfaction contrast, which related to the OO equal conditions, similarly found that high IJ participants (M = 4.8) were significantly more satisfied than low IJ participants (M = 1.85), t(33.19) = 9.42, p < .001. Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 462 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH DISCUSSION The current study investigated the fair process effect under conditions of varying knowledge of others’ outcomes. Levels of interactional justice were manipulated in a series of scenarios depicting face-to-face service recovery encounters set in the hospitality sector. Consistent with the hypothesis, it was found that irrespective of whether participants were aware or unaware of the outcomes of others, participants in conditions where the service provider was courteous and respectful (high IJ) perceived significantly higher levels of outcome fairness and reported significantly higher levels of satisfaction than participants in conditions where the service provider was rude and disrespectful (low IJ). Thus, the fair process effect was observed—interactional justice did make a difference—across all outcome conditions. These findings demonstrate that outcome evaluations are influenced by interactional elements even though information about others’ outcomes is available. More specifically, the results indicate that, at least within a hospitality service recovery setting, the interpersonal treatment of customers significantly affects evaluations of outcome fairness and satisfaction even when information about others’ outcomes is known. Thus, it appears that the present study’s focus on interactional fairness within a service recovery context has revealed at least one of the hitherto “unidentified conditions” to which Van den Bos, Lind, and colleagues (1997, p. 1043) alluded, where strong effects of procedures on outcome judgments are found despite the presence of social comparison equity information. Accordingly, it also appears that Van den Bos, Lind, and colleagues’ (1997) proposition concerning the redundancy of process information when social comparison equity data are present does not generalize to the present context. In contrast to the strong effect associated with interactional justice, the others’ outcomes manipulation yielded a more modest result. Although the multivariate effect associated with others’ outcomes was statistically significant, the stepdown test revealed that this effect was significant for fairness but not for satisfaction. Apparently, knowledge of others’ outcomes influenced participants’ evaluations of the fairness of the amount the customers paid but did not extend to satisfaction with the service encounter nor to future intentions in relation to the particular hospitality outlet. These findings imply that interactional justice has both a larger and a more pervasive influence on customer evaluations than is the case for social comparison equity information. The findings are consistent with those of Blodgett and colleagues (1997), who reported that interactional justice was a more potent determinant of complainants’ repatronage and negative word-ofmouth intentions than were either distributive or procedural justice. It is interesting that Blodgett and colleagues also reported a significant interaction between distributive and interactional justice, a finding not replicated here when knowledge of others outcomes was the independent variable. Procedural Versus Interactional Justice This study provided a partial replication of that conducted by Van den Bos, Lind, and colleagues (1997). That study’s finding that process factors affect out- Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 463 come evaluations only when others’ outcomes are unknown was not confirmed. The two studies differed in several ways, any of which may have contributed to the discrepant findings. For example, the multi-item measures of the dependent variables used in the current study may have produced more reliable and valid findings than those obtained previously. A second, more plausible basis for the different findings from the studies was the different type of process justice manipulated. Procedural justice was manipulated by Van den Bos, Lind, and colleagues (1997) and held constant in our research, whereas interactional justice was manipulated here but eliminated altogether in the experimental task used by Van den Bos, Lind, and colleagues. Although it is also possible that the discrepant findings can be partly explained in terms of the strength of these manipulations (an issue that should be put to future empirical test), it appears reasonable to conclude that the nature of the process justice manipulation, especially when combined with a congruent scenario that rendered this manipulation salient, was the most critical factor. To the extent that this is so, the contrasting findings of the two studies provide further evidence that the two forms of process justice are empirically distinctive and should be theoretically distinguished in future discussions. This stance might be further validated by future studies that include manipulations of high and low levels of both procedural and interactional justice, as well as social comparison equity information. Such research would provide an opportunity to further test Fairness Theory’s postulations regarding the relative importance and ease of interpretation of interactional, as compared with procedural, justice, and the consequent independent and interactive effects of these two forms of process justice on outcome fairness and related evaluations. Mechanisms Involved Our study did not explicitly focus on the mechanisms through which interactional justice has its effect on the participants’ evaluations. Certainly, the findings can be interpreted as being consistent with Fairness Theory’s (Folger & Cropanzano, 1998) postulation that it is the relative lack of ambiguity concerning interactional justice (at least when compared with procedural and distributive issues) that explains the potency of the obtained effects. However, a definitive test of this hypothesis would require the experimental manipulation of this ambiguity variable. If, however, a Fairness Theory approach is pursued, other possible mechanisms by which interactional justice influenced the results can be suggested. The Fairness Theory posits that a universal theme integrating the spectrum of justice models is the consideration of who is morally accountable for a perceived injustice and the direction of responses toward that party (Folger & Cropanzano, 1998). Using this framework, it could be inferred that in determining perceptions of moral accountability, participants in the low interactional justice conditions engaged in counterfactual comparisons of their experiences of rudeness and disrespect with (a) what should have been done (e.g., “I should have been treated politely and respectfully by the restaurant attendant”); (b) what feasibly could have been done (e.g., “The restaurant attendant could easily have been more cour- Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 464 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH teous, or more empathic toward my situation”); and (c) how they would have felt if something different had happened (e.g., “If only the restaurant attendant had been more polite, I would not have felt so upset”). Future research could be usefully directed toward explicating the counterfactual thinking that mediates the relationship between instances of injustice and the assignation of moral accountability. Such research would attempt to probe the participants’ thinking in the face of low interactional justice by the inclusion of measures of the participants’ perceptions of the extent to which (a) the service provider violated moral norms (what should they have done here?); (b) the service provider had discretionary control over alternative recovery options (what else could they have done?); and (c) how the customers’ feelings would have been different if other options had been adopted. Participants in conditions of high interactional justice, on the other hand, were placed in the role of a customer subjected to what Fairness Theory might term a positive “process event”. To date, the theory has not offered any substantive explanation of the psychological mechanisms underlying the more favorable evaluations likely to be elicited by experiences of perceived fairness. Accordingly, two alternate, and rather tentative, explanations for these results are tendered here. First, perhaps in the high interactional justice conditions, dignified and respectful treatment meets (“confirms”) participants’ implicit normative expectations (cf. Mattsson, 1994; Seiders & Berry, 1998). The confirmation of high interactional justice expectations may then elicit positive feelings in these participants, and these feelings may influence ratings of outcome fairness and satisfaction. A second possibility is that rather than producing positive feelings, service provider adherence to treatment norms may simply fail to produce negative affective responses (cf. Westbrook & Oliver, 1991). In other words, the norm of courteous and respectful treatment may be so embedded in the psyches of people in general, and customers in particular, that when received, it is scantly noticed. Perhaps, then, the issue of courteous and respectful treatment only becomes salient when it is not received. In short, a positive display of interactional justice may only be noticeable by its absence. Regardless of which explanation is adopted to explain the favorable evaluations under conditions of high interactional justice, it seems unlikely that the participants in these conditions would have perceived a need to assign moral accountability in these instances, because a violation of fundamental moral precepts had not occurred. Such positive process events, and their associated underlying psychological mechanisms, provide an avenue for future research into, and possible extensions to, Fairness Theory. Limitations As with all research methods, the approach taken here is limited in several ways. For instance, little published validity data appear to exist for the dependent measures, although they are reliable and arguably high in content validity. In addition, because the dependent measures assessed the subjective perceptions of participants, it may be useful for future studies to direct efforts to the development and utilization of behavioral measures to validate the perceptual data used in the current study. Another limitation is that the generalizability of the results may be Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 465 reduced because a student sample was utilized (cf. Brown et al., 1996; Clemmer, 1993; Goodwin & Ross, 1992). Future research could extend the sample to a broader representation of the consumer population. In addition, the findings might not be applicable to services or service failures other than those depicted in the scenarios (Clemmer, 1993; Goodwin & Ross, 1992). Yet, Lovelock and colleagues (1998) caution that it is equally unwise to “over-generalise about services [or] . . . assume that each service industry is unique” (p. 32). This suggests that the results may, at a minimum, apply to services that share certain fundamental characteristics with the hospitality services utilized in the current study. Finally, the use of projective, role-playing scenarios might also reduce the external validity of the findings (Barling & Phillips, 1993; Bitner, 1990; Brown et al., 1996). Participants could have experienced difficulty responding as they would if they were a customer in a similar, genuine service situation (Bitner, 1990; Blodgett et al., 1997). Against this, however, it should be noted that the mean response to the believability manipulation check (including the item “I was able to adopt the role of the customer depicted in the scenario”, see Table 1) exceeded 6 on the 7-point scale. Managerial Implications The results of this study have notable practical implications for hospitality and tourism organizations whose frontline staff interact directly with customers. Given that there is persuasive empirical evidence that customer evaluations of service encounters have important consequences for word-of-mouth behaviors and repeat business, there is a need for service organizations to devote resources to ensuring that service encounters seldom fail and, when they do, are always recovered. The results of the current study underscore the extent to which customer evaluations are shaped by perceptions of the interactional justice of the service encounter. Indeed, the results, in conjunction with similar findings from previous research, suggest that managers should pay more attention to devising and implementing policies that facilitate evaluations of high interactional justice. A number of complementary approaches can be taken to enhance and maintain high levels of interactional justice at the service provider–customer interface. First, service provider displays of dignity and respect may be influenced by the training policies of service organizations. The provision of appropriate interpersonal and communication skills training to customer contact employees appears extremely important for customer satisfaction and loyalty (see, e.g., Bitran & Hoech, 1990; Lewis & Entwistle, 1990). Given the salience of interactional concerns within the service recovery context of the current study, specific training in the courteous and respectful treatment of customers in service failure and recovery situations appears warranted. Although training frontline staff in interactional justice elements may be useful, some commentators highlight the inherent problems in the assumption that sociability toward customers is a skill that can be taught to employees (Hurley, 1998; Romm, 1989). Hurley (1998) suggests that, despite appropriate training and the support of organizational systems, not all people will “display the proper service behaviors consistently if their personality is not aligned with these types Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 466 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH of behavior” (p. 187). Hence, the recruitment and selection practices within service organizations may play a crucial role in facilitating the respectful and courteous treatment of customers. Thus, rather than focusing organizational energies exclusively on the training and development of frontline employees, it may prove equally fruitful to channel efforts into the recruitment of the types of people who will facilitate a positive service climate for both employees and customers alike (cf. Hurley, 1998). More generally, there is evidence that high levels of interactional justice will be manifested to the extent that a service climate characterized by courtesy and respect pervades the entire organization (Schneider, 1990). Although perhaps beyond the narrow scope of the current research, note can be taken of Schneider’s (1973) suggestion that the work climate created by service organizations for their employees influences employee behavior toward customers. Hence, it appears that it is not enough for service organizations to require employees to treat customers politely and respectfully; leaders and managers within organizations should create a climate of respect and dignity through their own treatment of employees (Bitran & Hoech, 1990; Bowen et al., 1999). CONCLUSION The present study offers important theoretical and practical insights into justice concerns within the hospitality and tourism sector organizations. Evidence was found consistent with Fairness Theory’s proposition that interactional justice may be the most potent moderator of reactions to unfair outcomes. The results also suggest that, at least in service recovery settings, interactional justice functions differently from procedural justice, thus lending support to the theoretical differentiation of these two organizational justice dimensions. The placement of the research within a service recovery environment yielded the first known context where fair process effects were found despite the presence of social comparison equity information. Hence, the findings suggest the claim that procedural justice information is redundant when others’ outcomes are known does not generalize to service recovery environments. The importance of dignified and respectful treatment of customers (and employees) by service organizations is also highlighted, with implications for service climate creation and the training and selection of customer contact staff. Thus, amid the continuing complexity of the justice construct, the current study might be best encapsulated by the simple words of Bell and Zemke (1987): “When service fails, first treat the person, then the problem” (p. 34). Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 467 APPENDIX Sample Scenario Instructions: READ THE FOLLOWING SCENARIO AND IMAGINE THIS HAPPENED TO YOU. Imagine you are on a day trip arranged by the student guild to one of the local theme parks. Although there is a whole bus load of students, you don’t know many people. When you arrive at the theme park, the bus load splits up into lots of small groups, and you head off with a student you recently met in one of your tutorials. After enjoying some of the rides, you and your new friend decide to eat. As part of the arrangement with the theme park, the student guild has given each student a lunch coupon that allows you to buy a set meal from the main restaurant for a low $8 (meals normally start at $12). However, when you go to order the meal, the following occurs: The attendant smiles/frowns and asks pleasantly/abruptly, “What would you like?” “I have this special coupon for an $8 meal—I’d like to order that please.” The attendant takes the coupon from you with an interested/disinterested look on their face. After inspecting the coupon, the attendant, sounding concerned/indifferent says, “I’m really very sorry/I’m sorry. These coupons are out of date—we stopped taking them last month.” Seeming slightly perplexed/annoyed, the attendant continues, “You can see that the use-by date is written right here on the coupon. That was over two weeks ago.” “But the coupon is part of the package that we all received today! We’re all from the uni, and our student guild organised them especially with the theme park for us to use today,” you reply emphatically. At this point the attendant seems to become very understanding/agitated,and, in a sympathetic/irritated voice, says, “This meal is usually $12. What would you like us to do?” “Well at the very least I’d like to get what is on the coupon!” you respond. The attendant then replies sincerely/abruptly, “I know this must be very frustrating for you/You people always want something for nothing. I’ll just have to go and check.” The attendant walks over to the counter and returns with a pre-printed visitor comment card that they place/thrust in front of you. Smiling/glaring, the attendant says, “Seeing as I have to refer to the manager, it’s the park’s policy that you are given the opportunity/get to fill in one of our feedback cards.” The attendant gives you a pen and then leaves to consult with the manager. Whilst the attendant is away, you record the details of the incident on the feedback card. The attendant returns and says very politely/huffily, “No problem/Well you’re in luck . . . . you can have the meal for $8.” You and your friend place your order for the discount meals. As you leave the restaurant after finishing your meal, you hand the attendant feedback card and think to yourself, “Well at least I had a say about that.” Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 468 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH Later, at the pre-arranged time, all the students meet back at the bus. On the journey back to uni, you overhear two students sitting across the aisle from you talking about the lunch coupons. You ask them whether they’d had any problem ordering the meal on the coupon, to which one of them replies [equal outcome] “Yeah, they wanted to charge us $12, but we ended up getting it for $8—the amount on the coupon!” [better outcome] “Yeah, they wanted to charge us $12, but we ended up getting it for $4—even less than the amount on the coupon!” [worse outcome] “Yeah, they wanted to charge us $12, and that’s what we ended up having to pay!” [unknown] “Yeah,” and then they continued their own conversation. Straight after the other student’s reply, the bus arrives back at uni. Everyone immediately leaves the bus and goes their separate ways. Note: Experimental manipulations are italicized. IJ manipulations appear throughout the scenario text, with high IJ scenario text appearing first in the italicized text. Manipulations of the second independent variable, OO, appear in the second last paragraph of the scenario text. Each participant received one of the eight versions of the scenario (2 [IJ] × 4 [OO] manipulations). NOTES 1. In accordance with much of the literature (see, e.g., Brockner & Wiesenfeld, 1996; Folger & Cropanzano, 1998; Lind & Tyler, 1988), the terms fairness and justice, and distributive and outcome, are used interchangeably throughout this article. 2. Full details of the items used are available from the first author on request. REFERENCES Adams, J. S. (1963). Toward an understanding of inequity. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(5), 422-436. Barling, J., & Phillips, M. (1993). Interactional, formal, and distributive justice in the workplace: An exploratory study. Journal of Psychology, 127(6), 649-656. Bazerman, M. H. (1993). Fairness, social comparison, and irrationality. In J. K. Murnighan (Ed.), Social psychology in organizations: Advances in theory and research (pp. 184-203). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Bell, C. R., & Zemke, R. E. (1987, October). Service breakdown: The road to recovery. Management Review, 76, 32-35. Bies, R. J. (1987). The predicament of injustice: The management of moral outrage. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 9, pp. 289-319). Greenwich, CT: JAI. Bies, R. J. & Moag, J. S. (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. In I. R. Lewicki, M. Bazerman, & B. Sheppard (Eds.), Research on negotiation in organizations (Vol. 1, pp. 43-55). Greenwich, CT: JAI. Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 469 Bies, R. J., & Shapiro, D. L. (1987). Interactional fairness judgments: The influence of causal accounts. Social Justice Research, 1(2), 199-218. Bitner, M. J. (1990, April). Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. Journal of Marketing, 54, 69-82. Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Mohr, L. A. (1994, October). Critical service encounters: The employee’s viewpoint. Journal of Marketing, 58, 95-106. Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Tetreault, M. S. (1990, January). The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. Journal of Marketing, 54, 71-84. Bitran, G. R., & Hoech, J. (1990). The humanization of service: Respect at the moment of truth. Sloan Management Review, 31(2), 89-96. Blodgett, J. G., & Granbois, D. H. (1992). Toward an integrated conceptual model of consumer complaining behavior. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior, 5, 93-103. Blodgett, J. G., Hill, D. J., & Tax, S. S. (1997). The effects of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice on postcomplaint behavior. Journal of Retailing, 73(2), 185-210. Boshoff, C. (1997). An experimental study of service recovery options. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8(2), 110-130. Boshoff, C. (1999). RECOVSAT: An instrument to measure satisfaction with transaction-specific service recovery. Journal of Service Research, 1(3), 236-249. Bowen, D. E., Gilliland, S. W., & Folger, R. (1999). HRM and service fairness: How being fair with employees spills over to customers. Organizational Dynamics, 27(3), 7-23. Brockner, J., & Wiesenfeld, B. M. (1996). An integrative framework for explaining reactions to decisions: Interactive effects of outcomes and procedures. Psychological Bulletin, 120(2), 189-208. Brown, S. W., Cowles, D. L., & Tuten, T. L. (1996). Service recovery: Its value and limitations as a retail strategy. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 7(5), 32-46. Clemmer, E. C. (1993). An investigation into the relationship of fairness and customer satisfaction with services. In R. Cropanzano (Ed.), Justice in the workplace: Approaching fairness in human resource management (pp. 193-207). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Clemmer, E. C., & Schneider, B. (1996). Fair service. In T. A. Swartz, D. E. Bowen, & S. W. Brown (Eds.), Advances in service marketing and management: Research and practice (Vol. 5, pp. 109-126). Greenwich, CT: JAI. Cropanzano, R., & Greenberg, J. (1997). Progress in organizational justice: Tunneling through the maze. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 317-372). New York: John Wiley. Czepiel, J. A. (1990). Service encounters and service relationships: Implications for research. Journal of Business Research, 20, 13-21. Czepiel, J. A., Solomon, M. R., Surprenant, C. F., & Gutman, E. G. (1985). Service encounters: An overview. In J. A. Czepiel, M. R. Solomon, & C. F. Surprenant (Eds.), The service encounter: Managing employee/customer interaction in service businesses (pp. 3-15). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. De Vaus, D. A. (1995). Surveys in social research. St. Leonards, Australia: Allen and Unwin. Dubé, L., & Menon, K. (1998). Why would certain types of in-process negative emotions increase post-purchase consumer satisfaction with services? Insights from an interper- Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 470 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH sonal view of emotions. In T. A. Swartz, D. E. Bowen, & S. W. Brown (Eds.), Advances in services marketing and management (Vol. 7, pp. 131-158). Greenwich, CT: JAI. Folger, R. (1993). Reactions to mistreatment at work. In J. K. Murnighan (Ed.), Social psychology in organizations: Advances in theory and research (pp. 161-183). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Folger, R., & Bies, R. J. (1989). Managerial responsibilities and procedural justice. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2(2), 79-90. Folger, R., & Cropanzano, R. (1998). Organizational justice and human resource management. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Goodwin, C., & Ross, I. (1989). Salient dimensions of perceived fairness in resolution of service complaints. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior, 2, 87-92. Goodwin, C., & Ross, I. (1992). Consumer responses to service failures: Influence of procedural and interactional fairness perceptions. Journal of Business Research, 25, 149-163. Greenberg, J. (1987). A taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Academy of Management Review, 12(1), 9-22. Greenberg, J. (1990). Organizational justice: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Journal of Management, 16(2), 399-432. Hair, J., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1995). Multivariate data analysis with readings (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Hocutt, M. A., Chakraborty, G., & Mowen, J. C. (1997). The impact of perceived justice on customer satisfaction and intention to complain in a service recovery. In M. Brucks & D. J. MacInnis (Eds.), Advances in consumer research(Vol. 24, pp. 457-463). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research. Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behaviour: Its elementary forms. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Hurley, R. F. (1998). Service disposition and personality: A review and a classification scheme for understanding where service disposition has an effect on customers. In T. A. Swartz, D. E. Bowen, & S. W. Brown (Eds.), Advances in services marketing and management (Vol. 7, pp. 159-191). Greenwich, CT: JAI. Iacobucci, D., Ostrom, A., & Grayson, K. (1995). Distinguishing service quality and customer satisfaction: The voice of the consumer. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 4(3), 277-303. Johnston, R. (1995). Service failure and recovery: Impact, attributes and process. In T. A. Swartz, D. E. Bowen, & S. W. Brown (Eds.), Advances in services marketing and management (Vol. 4, pp. 211-228). Greenwich, CT: JAI. Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (1997, July-August). Fair process: Managing in the knowledge economy. Harvard Business Review, 65-75. Korsgaard, M. A., Schweiger, D. M., & Sapienza, H. J. (1995). Building commitment, attachment, and trust in strategic decision-making teams: The role of procedural justice. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 60-84. Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchanges: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27-55). New York: Plenum. Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 Collie et al. / INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE 471 Lewis, B. R., & Entwistle, T. W. (1990). Managing the service encounter: A focus on the employee. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 1(3), 41-52. Lind, E. A., & Lissak, R. I. (1985). Apparent impropriety and procedural fairness judgments. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 21, 19-29. Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum. Lovelock, C. H., Patterson, P. G., & Walker, R. H. (1998). Services marketing: Australia and New Zealand. Sydney, Australia: Prentice Hall. Mattila, A. S. (1999). An examination of factors affecting service recovery in a restaurant setting. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 23(3), 284-298. Mattsson, J. (1994). Improving service quality in person-to-person encounters: Integrating findings from multi-disciplinary review. The Services Industries Journal, 14(1), 45-61. Mikula, G. (1986). The experience of injustice: Toward a better understanding of its phenomenology. In H. W. Bierhoff, R. L. Cohen, & J. Greenberg (Eds.), Justice in social relations (pp. 103-123). New York: Plenum. Nikolich, M. A., & Sparks, B. A. (1995). The hospitality service encounter: The role of communication. Hospitality Research Journal, 19(2), 43-56. Oliver, R. L., & Swan, J. E. (1989, April). Consumer perceptions of interpersonal equity and satisfaction in transactions: A field survey approach. Journal of Marketing, 53, 21-35. Price, L. L., Arnould, E. J., & Deibler, S. L. (1995). Consumers’ emotional responses to service encounters: The influence of the service provider. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 6(3), 34-63. Price, L. L., Arnould, E. J., & Tierney, P. (1995, April). Going to extremes: Managing service encounters and assessing provider performance. Journal of Marketing, 59, 83-97. Roese, N. J. (1997). Counterfactual thinking. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 133-148. Roese, N. J., & Olson, J. M. (1997). Counterfactual thinking: The intersection of affect and function. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 29, pp. 1-59). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Romm, D. (1989). “Restauration” theater: Giving direction to service. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 29(4), 31-39. Schneider, B. (1973). The perception of organizational climate: The customer’s view. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57, 248-256. Schneider, B. (1990). The climate for service: An application of the climate construct. In B. Schneider (Ed.), Organizational climate and culture (pp. 383-412). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Schneider, B., & Bowen, D. E. (1985). Employee and customer perceptions of service in banks: Replication and extension. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(3), 423-433. Schneider, B., Parkington, J. J., & Buxton, V. M. (1980, June). Employee and customer perceptions of service in banks. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25, 252-267. Seiders, K., & Berry, L. L. (1998). Service fairness: What it is and why it matters. Academy of Management Executive, 12(2), 8-20. Siehl, C., Bowen, D. E., & Pearson, C. M. (1992). Service encounters as rites of integration: An information processing model. Organization Science, 3(4), 537-555. Solomon, M. R., Surprenant, C.C.J.A., & Gutman, E. G. (1985, Winter). A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: The service encounter. Journal of Marketing, 49, 99-111. Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014 472 JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY & TOURISM RESEARCH Sparks, B. A., & McColl-Kennedy, J. R. (2000). Justice strategy options for increased customer satisfaction in a service recovery setting. Journal of Business Research, 50, 1-10. Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (1996). Using multivariate statistics (3rd ed.). New York: HarperCollins. Tax, S. S. (1993). The role of perceived justice and complaint resolutions: Implications for services and relationship marketing. Dissertation Abstracts International, 54(7), 26547A. Tax, S. S., & Brown, S. W. (1998). Recovering and learning from service failure. Sloan Management Review, 40(1), 75-88. Tax, S. S., Brown, S. W., & Chandrashekaran, M. (1998). Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: Implications for relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 62, 60-76. Thibaut, J., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Tyler, T. R., & Bies, R. J. (1990). Beyond formal procedures: The interpersonal context of procedural justice. In J. S. Carroll (Ed.), Applied social psychology and organizational settings (pp. 77-98). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Van den Bos, K., Lind, E. A., Vermunt, R., & Wilke, H.A.M. (1997). How do I judge my outcome when I do not know the outcome of others? The psychology of the fair process effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1034-1046. Van den Bos, K., Wilke, H.A.M., Lind, E. A., & Vermunt, R. (1998). Evaluating outcomes by means of the fair process effect: Evidence for different processes in fairness and satisfaction judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1493-1503. Westbrook, R. A., & Oliver, R. L. (1991, June). The dimensionality of consumption emotion patterns and consumer satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 18, 84-91. Zemke, R., & Bell, C. (1990). Service recovery: Doing it right the second time. Training, 27(6), 42-48. Submitted October 28, 1999 Accepted January 1, 2000 Refereed Anonymously Thérèse A. Collie (e-mail: t.collie@gu.edu.au) is a senior research assistant, and Beverley Sparks, Ph.D. (e-mail: b.sparks@gu.edu.au), is an associate professor, in the School of Tourism and Hotel Management at Griffith University, Gold Coast (PMB 50, Gold Coast Mail Centre, QLD, Australia 9726); and Graham Bradley (e-mail: g.bradley@mailbox.gu.edu.au) is a senior lecturer in the School of Applied Psychology at Griffith University, Gold Coast (PMB 50, Gold Coast Mail Centre, QLD, Australia 9726). Downloaded from jht.sagepub.com at FLORIDA INTL UNIV on August 27, 2014