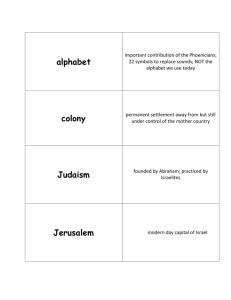

HEBREW SYNCRETISM DURING THE PATRIARCHAL ERA: A STUDY THAT CHALLENGES THE ABRAHAM AUTHORSHIP OF MONOTHEISM BY YEJOJANAN AJENATON LOPEZ GALVAN The three monotheistic religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islamism, are commonly known as Abrahamic religions. This collective designation is because Abraham, the ancient Hebrew patriarch, is thought to have been the first monotheist in history. However, a deep study of the content of some biblical texts, in which the name of Yahweh is involved, and its null relation with the patriarchal epithets for divinity, will teach us that there is no connection it gives food for thought that the patriarchs knew the God of Moses. From what is expressed in Exodus 3:13 it is evident that the "God of the Hebrews" was completely unknown to them until the time of Moses. Judging by Moses' question, "and they shall say to me, What is his name? what shall I say unto them?", neither the Hebrews nor Moses himself knew that they had a God to worship. The proclamation of Yahweh's name to the prophet is of fundamental importance if one considers what it meant to have a name at that time: he who has a name exists; he who does not have a name does not exist. The importance of knowing the specific name of a deity in antiquity in relation to its worshipers is made clear in a Jewish writer statement: "Among the ancient Semites, as among almost all primitive peoples, the name is an indispensable part of the being of the deity. Until his true name is known, so that he may be distinguished from that of all other gods and prayers and sacrifices may be addressed to him in person, it is absolutely impossible to worship him".1 Moses' own statement that "the God of the Hebrews hath met with us" (Exodus. 5:3) ratifies that until then the Israelites had no deity to worship except the divinities of the Egyptians. Nor is there the slightest biblical evidence that Israel had a temple or priesthood dedicated to Yahweh during the entire time they were residing in Egypt. This reinforces the argument that the Hebrews 1 Julian Morgenstern, As A Migthy Stream. The Progress of Judaism Trough History, p. 37. 1 did not know Yahweh at the time they descended into the country of the Nile. With this, we have that the mentions of Yahweh's name in Genesis, prior to the announcement at Sinai, constitute a true anachronism that the author, evidently not Moses, has not made an effort to avoid. In addition to the above, in the Bible is the outstanding testimony about the time since Yahweh is the God of Israel: "Yet I am the Lord thy God from the land of Egypt... I did know thee in the wilderness, in the land of great drought". (Hosea 13:4,5). This does not mean that God did not exist until he made himself known to Moses; but this verse proves that it was only until he deigned to reveal his name that Israel came to be aware of his existence. It seems to me that, then, based on the concept of the name, and in view of the fact that neither the patriarchs, nor the Israelites prior to Moses, not even Moses himself knew the name of God before his announcement at Horeb, along with the fact that, as has been pointed out, there is no evidence showing Israel worshipped Yahweh in Egypt, it is because they did not really have a definitive idea of his existence. Now, it is true that in Exodus. 6:3 there is an effort to try to identify Yahweh with the deity of patriarchal times. But a philological consideration of the terms applied to the divinity at that time will result in an additional clarification that, as we have already anticipated, there is no relationship between Yahweh's name and patriarchal allusions. First than all, the word translated "God" in the Bible was the Semitic term אלל (el), common throughout the Canaanite sphere. The word in question was used to refer to divinity in general, without specifying which particular deity was alluded to. Prof. Moisés Chávez, a Christian scholar of the Hebrew language, points this out: "The word א ללseems to have been used as a determinative, equivalent either to Sumerian DINGIR or Acadian ILU... As such, it preceded the names of the various divinities".2 2 Moisés Chávez, Hebreo Bíblico (Biblical Hebrew), Vol. I, pp. 449, 450. The texts, originally in Spanish, have been translated into English by me. 2 This means that the term with which the patriarchs alluded to deity was such a vague and generalized word that it resists any attempt at nominal identification. Other terminology were needed, almost always qualifying adjectives from אלל. Those other adjectives occur in the Bible, especially in Genesis; but Chávez implicitly admits that such Hebrew terms, which describe the patriarchal deity and accompany the indefinite אלל, are not names of the God of Israel, but only epithets, some of which were also used alongside specific Canaanite deities. Among the eight epithets with which the patriarchal divinity was alluded to, gathered on page 450 of the first volume of his work, Chávez found some that had originally been applied to Canaanite deities at the time of the patriarchs. An example of this association is the term ( ש) יד) ייshaddai), which has always been translated as "the Omnipotent" or "the Almighty".3 In this regard, the author identifies the linguistic origin of the word and its etymological definition: "Now that Ugaritic literature has been discovered, Shaddai (appears) in epithets of the goddess Ashtoret or Astarte. The word seems to mean ¨mountain¨ or ¨mount¨; then, EL SHADDAI would mean "the God of the mount' ".4 Concerning another of the ancient epithets of the deity, ( אללוהelóah), Chávez writes: " אללה) יwould have been an ancient designation of the divinity in Aram-Syria, which, in its original Aramaic ( לאלההread: Elah), makes its way through history... about the possible meaning of אלל ) יהit would have been the name of the divinity upon whose attendance and patronage the covenants were celebrated. This is deduced from the word ( אלההalah) which means 'covenant'... A semantic equivalent of אלההwould be the word ( בההתייתberith), meaning also 'covenant', and which was too the name of a divinity that had its temple at Shechem. In the Bible it is called ( ) יבע) יל ב תירריתBa´al berith) "The divinity of the covenant" Judges. 9:4".5 3 It occurs for the first time in Gen. 17:1: "I am the Almighty God". In Hebrew transcription El shaddai. 4 Op. cit., p. 252. Although Chavez has found the origin and correct meaning of the term SHADDAI, he errs in anachronistically identifying the mountain with Sinai, since in Abraham's day there was no knowledge of this mountain and that there would be Yahweh's revelation. 5 Op. cit., p. 454. 3 This author still has an additional opinion on another of the terms used by the patriarchs to refer to deity: '( אלל בלית־אללel beth-'el) "The god of Beth´el" (Gen. 35:7): "The structure of this name, which is a genitive association, allows it to be translated as follows: ´el god of Bethel´. Here we have a hint that Bethel was in ancient times the center of worship of a Canaanite god. Moreover, it seems, according to documents of Ugarit, that there was a god whose name was Bethel".6 What conclusion does Prof. Chavez reach in light of this unobjectionable evidence provided by Scripture itself? Let us read his sincere statement: "It is very difficult to separate the history of Genesis 35 from its polytheistic associations".7 Therefore, on the basis of what we have considered here, regarding the epithets that the patriarchs applied to divinity were the same with which the pre-Israelite Canaanites named their gods, we can now see that the Exodus statement in 6:3., is nothing more than a futile effort by some post-Moses editor to try to identify Yahweh with the unnamed and suspiciously polytheistic patriarchal deity. The lack of total relationship between the sole God of Moses and the idolatrous references to the divinity of the patriarchs, one has only to admit that the statement in Exodus. 6:3 it is but one of the many interpolations in the Bible to try to resolve many other inconsistencies. These subsequent editions to the text were obviously not of the original writer, Moses in this case, but of those who, as the Bible itself testifies, later assigned to the unique God of the prophet not only the names of the Canaanite gods, but also most of their characteristics. If the patriarchs worshipped their god with identical epithets belonging to Ashtoret, Baal and Bethel, all these authentically Canaanite gods, then it was not Yahweh who worshiped, because according to the prophets, he never 6 Op. cit., p. 453. The great investigator of the ancient religious phenomenon, Mircea Eliade, states of Bethel: "The texts of Ras Shamra, which are precious documents on the religious life of the pre-mosaic Semites, show that El and Beth-el are interchangeable names of the same divinity. Treatise on the History of Religions, p 213. 7 Same page as above, final paraghraph 4 liked not only to be worshipped alongside with strange gods, but also did not like being identified with the various names of these other gods. 8 Neither Abraham, nor his descendants by the lines of Isaac and Ishmael, therefore, were aware of what monotheism meant, and the statement of the Talmud, which attributes to the first Hebrew patriarch to be the father of monotheism, can only be considered as a subjective aphorism, devoid of any documentary basis that supports it. On the other hand, the Muslim assertion that Ibrahim (Abraham) knew monotheism is more out of place here. History bears witness that the great Arab nation, descendant of Ishmael, the son of Abraham, was immersed in polytheism for a long time until the 6th century A.D., when the prophet Muhammad converted it to monotheism. This logically means that Ishmael could not learned monotheism from Abraham because, according to the above Bible data, the latter did not know it either. In conclusion, and based on both internal and external evidence, Jews, Christians and Muslims can only acknowledge that, apart from the fact that the epithets with which the deity was designated in patriarchal times suggest a high degree of anonymity and impersonality, the associations of these epithets with some pre-Israeli Canaanite deities place the Hebrew divinity within a clearly polytheistic environment, completely apart to the elevated monotheistic concept of Moses. This monotheistic idea of the Hebrew prophet has more resemblance, both symbolically and phenomenologically, with the monotheism of the Pharaoh Akhenaten. But this will be the subject of another study. COPYRIGHT NOTE Copyright © 2019 by Juan José López Galván All rights reserved. No portion of this paper may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. 8 Remember here Hosea 2:6: "And it shall be at that day, saith the Lord, that thou shalt call me Ishi; and shalt call me no more Baali"; that is, my Baal. Ba´al was the original name of the popular Canaanite deity before the entrance of Israel into Canaan. Grammatical note: the i after the name is a Hebrew pronominal suffix of pocession meaning "my". "mine". Baali, therefore, mean, "My Baal". 5