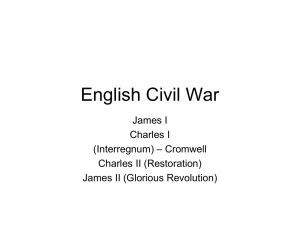

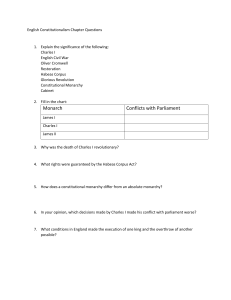

The First English Revolution (called the English Civil War by British historians) is also called the Great Rebellion. The events that happened between 1642-1651 were the result of the Stuart monarchy government of the Kingdom of England. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. The Civil War broke out in England due to the reign of Charles I. Starting in 1603, only one king reigned over England, Wales, and Scotland. However, Scotland and England were still two separate kingdoms, each with its own Parliament. Charles I, who ascended to the throne in 1625, wanted to achieve the ambitions of his father, James Stuart, of unifying England, Scotland, and Ireland under the same kingdom. Charles’ aspirations worried some Englishmen who feared for their rights. Charles, like his father, claimed the divine right of kings to rule without impediment and did not accept the limits that tradition imposed on the King of England. In 1625, Charles controversially married the Catholic Henrietta Maria of France, which upset the predominantly Protestant nation. In 1640, Charles needed to impose new taxes to react to rebellions. A new Parliament was convened, which took the opportunity to air grievances over the king’s conduct. Charle I dissolved Parliament after a few weeks (this is known as the Short Parliament). Charles resumed the war in Scotland without further financial resources. As such, he was forced to convene a new parliament in November. The new parliament was even more hostile to Charles, and it passed several laws to defend its rights against the royal power. Parliament forbade the King from dissolving it. From then on, the King was advised on various ways to resolve the conflict. Charles I opposed each proposition made to him by stating that they threatened the royal institution and his divine right to rule as he pleased. It was precisely for these reasons that the Civil War started. This revolution ended with the execution of King Charles I on 30 January 1649, at Whitehall (near Westminster, in London). The monarchy was abolished, and a republic, called the Commonwealth of England, was established with Oliver Cromwell at its head. Such a revolution in England and Europe was a crucial step in the transformation of English royal power, which would gradually move towards a constitutional monarchy. When Elizabeth I died without heirs in 1603, the throne of England and Ireland passed to her closest relative, James Stuart (who was already king of Scotland under the name of James VI). He, therefore, assumed the English crown with the name of James I of England. For the first time, Anglican England, Catholic Ireland, and Calvinist Scotland were united under the same sovereign. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. The reign of James (which lasted until 1625) was an age of strong contrasts and divisions that affected all areas, especially religion. Although the king was committed to supporting Anglicanism, he often acted in favour of Catholicism. The Puritan movement, which was especially popular amongst the upper classes, sought a more orthodox Calvinist approach and wanted a model of society where the individual was responsible for their faith and choices. Following the reign of James I, the English throne passed to his son Charles I. During this period, conflict between the king and Parliament exploded mainly due to tax issues. His marriage to Henrietta Maria, daughter of King Henry IV of France (a fervent Catholic), as well as the appointment of William Laud to Archbishop of Canterbury (1633), alienated the king from the Anglican majority, which followed Calvinist ideas. Charles I, therefore, exacerbated the divisions of the country over religion and the management of power. In 1628, Parliament voted on the Petition of Right according to which the king could not impose taxes without Parliamentary approval: not imprison a free man without a trial; not subject free men to special courts; not force freemen to lodge troops in their homes. The king disputed these rights and established monarchical tribunals, denying all free men to be judged by their peers, thus causing significant tension between the people’s representatives and the monarchy. Furthermore, although it was forbidden, Charles I was still collecting taxes. In fact, among other things, he had imposed an unpopular tax that maritime cities had to pay in times of war. The king evaded the Petition of Right and extended the tax to all his subjects. Since such a tax would have made sense only in times of war, the king decided to take part in the conflict in Scotland to justify his tax. Charles’ intention was that of conquering Ireland. However, to do this, he needed an army. The Irish question became a problem that set the stage for the English Revolution. In 1629, Charles dissolved Parliament and started a personal government. As a result, discontent grew. One of the contributing factors that led the king to dissolve Parliament was the religious question of continuing to support the Anglican church since Charles proved hostile towards the religious tendencies of many of his English and Scottish subjects. In 1628, a Puritan movement arose, asking for a church very similar to the Scottish one. Faced with the demand for a new social and economic order, Parliament was dissolved again, and the King began an absolutist policy. To avoid appearing in contradiction to his position on religious matters, Charles wanted to impose the English religion on Calvinist 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. Scotland. The Scots rejected this, however, and declared war on Charles. At that time, though, the army was stationed in Ireland, where religious conflicts arose between Catholics and Calvinists. This caused many problems for the English Crown. In fact, in 1641, a revolt had broken out in Ireland wherein landowners, free men, and Catholic peasants rose against the nascent class of English Protestant settlers. Charles, therefore, was forced to give in and tolerated the Presbyterian church in Scotland. The king was forced to reconvene Parliament, among whose members was John Pym, one of the most important figures of this period. He took advantage of the situation to incite the Scottish people to point their guns at the king. When the royal army returned from Ireland, it fell under the command of John Pym (who became “the other king”). Parliament, with the Grand Remonstrance, approved 200 articles of the Magna Carta. Each article was directed towards the Stuart family, especially the king. In 1628, in order to support the Netherlands in their military expenses against Spain, Charles I summoned Parliament. However, instead of granting subsidies to the king, parliamentarians asked him to take responsibility for all of his illegal actions. Charles was asked to sign the Petition of Rights, with which it was decreed that every tax had to be approved by Parliament, while other practices – such as forced loans, obligatory recruitment, and unjustified arrests – were illegal. For this reason, the king dissolved Parliament just a month later. During the ten years of Parliament’s absence, Charles I, supported by Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud and the Crown Council, tried to raise money through the imposition of new taxes. He also attempted to spread Anglicanism in Scotland, a country of Calvinist faith, causing a revolt. Charles I was forced to summon Parliament to ask for the approval of further taxes necessary to form an army to deal with insurgents. This happened on 13 April 1640 (Short Parliament), and Charles I tried to obtain Parliament’s favour through the abolition of the Ship Money tax. Parliament, which was composed of 33% Puritan representatives, responded by criticising Charles I’s policies and decreed the suspension of subsidies. The king responded with the dissolution of parliament on 5 May 1640. The king tried to get rid of the parliamentarians who were most hostile to him. However, through being warned in advance, they managed to save themselves through the support of the people of London, who were growing increasingly impatient with Charles I’s attitude. Thus, a civil war broke out between monarchists and 26. parliamentarians (nicknamed Roundheads by their opponents because of their hairstyle compared to those of the king’s troops). Initially, the monarchists prevailed, but after a short time, the situation was reversed. The desperate king tried to negotiate with the Scots, who arrested him and sold him to parliamentarians. Charles I managed to escape, however, and the war continued for another year. In the end, Parliament won. The leader of the parliamentarians, Oliver Cromwell, expelled the monarchists from parliament, the king was sentenced to death, and the English or Commonwealth Republic was proclaimed. Cromwell assumed leadership of the Commonwealth as Lord Protector of the Kingdom. 27. 28. 29. 30. The first and second English civil wars happened between 1642– 1646 and 1648–1649, respectively. The major battle fought during this time was the Battle of Edgehill on 23 October 1642. Both Charles I and Parliament’s armies had 60,000 to 70,000 men in the field. Another battle fought in the earlier series of civil wars was the Battle of Marston Moor on 2 July 1644. Charles I enforced 11,000 Royalist infantry in this war but was eventually defeated by the overwhelming 31. 32. 33. 20,000 Parliament and Scottish infantry. This loss greatly frustrated the king. The Battle of Naseby occurred on 14 June 1645, and it was a turning point for Cromwell and the anti-royalists because it brought a series of successes for their side. On 5 May 1646, Charles I surrendered to the Scots at Newark and was imprisoned by the army until 1648. The third English civil war happened between 1649 and 1651. It pitted the supporters of King Charles II, the son of Charles I, against the supporters of the Rump Parliament. It ended with the victory of Parliament in the Battle of Worcester on 3 September 1651. The English civil wars resulted in the (1) trial and execution of Charles I, (2) exile of Charles II, and (3) replacement of England’s monarchy with the Commonwealth of England (1649–1653) and the Protectorate (1653–1659) led by Oliver Cromwell. Ultimately, it established the idea that an English monarch cannot govern without the consent of Parliament. However, the ruling power of Parliament was only formally established during the Glorious Revolution in 1688.