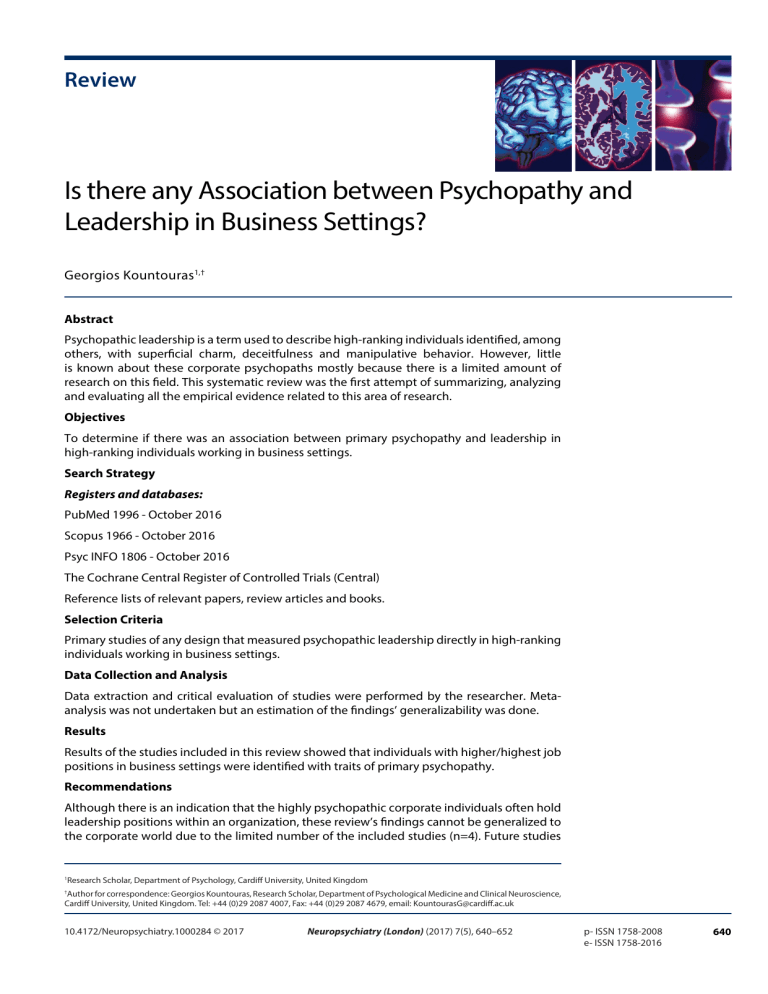

Review Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? Georgios Kountouras1,† Abstract Psychopathic leadership is a term used to describe high-ranking individuals identified, among others, with superficial charm, deceitfulness and manipulative behavior. However, little is known about these corporate psychopaths mostly because there is a limited amount of research on this field. This systematic review was the first attempt of summarizing, analyzing and evaluating all the empirical evidence related to this area of research. Objectives To determine if there was an association between primary psychopathy and leadership in high-ranking individuals working in business settings. Search Strategy Registers and databases: PubMed 1996 - October 2016 Scopus 1966 - October 2016 Psyc INFO 1806 - October 2016 The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Central) Reference lists of relevant papers, review articles and books. Selection Criteria Primary studies of any design that measured psychopathic leadership directly in high-ranking individuals working in business settings. Data Collection and Analysis Data extraction and critical evaluation of studies were performed by the researcher. Metaanalysis was not undertaken but an estimation of the findings’ generalizability was done. Results Results of the studies included in this review showed that individuals with higher/highest job positions in business settings were identified with traits of primary psychopathy. Recommendations Although there is an indication that the highly psychopathic corporate individuals often hold leadership positions within an organization, these review’s findings cannot be generalized to the corporate world due to the limited number of the included studies (n=4). Future studies Research Scholar, Department of Psychology, Cardiff University, United Kingdom 1 Author for correspondence: Georgios Kountouras, Research Scholar, Department of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neuroscience, Cardiff University, United Kingdom. Tel: +44 (0)29 2087 4007, Fax: +44 (0)29 2087 4679, email: KountourasG@cardiff.ac.uk † 10.4172/Neuropsychiatry.1000284 © 2017 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5), 640–652 p- ISSN 1758-2008 e- ISSN 1758-2016 640 Review Georgios Kountouras on psychopathic leadership should have a longitudinal methodological design in order to investigate if specific psychopathic traits are responsible for leadership development. Keywords: Psychopathy, Socio-cultural contexts, Sociopathy, Leadership in Business Introduction Along history and across many different sociocultural contexts, there have been described few individuals with specific characteristics such as callousness, irresponsibility, aggressive and impulsive behavior, lack of empathy and guilt combined with a pathological tendency to deceitfulness [1]. In the modern psychiatric practice, these individuals have been categorized in the most widely used classification systems of mental disorders, DSM-5 and ICD-10, under terms that are often used interchangeably not only by mental health professionals, but also by media and non-specialists [2]. As both DSM’s and ICD’s editions have changed multiple times over the past decades, the terms used to describe and classify these individuals with these particular traits have changed too. From the initial terms of psychopathy and sociopathy included in the first editions of DSM and ICD respectively, psychiatrists and psychologists are using now the diagnostic categories of either antisocial personality disorder (APD) or dissocial personality disorder (DPD) (which has a lesser stigmatizing effect), depending on the classification system that they use in their clinical practice [3]. However, the terms of psychopathy and sociopathy continue to emerge in many contexts. For example, in the legal context, psychopathy characterizes an individual with a severely criminal and ruthless behavior despite the fact that this individual will be possibly diagnosed with an antisocial or dissocial personality disorder in the psychiatric context [3]. Apart from the above-mentioned alterations in the use of terms regarding each context that have little practical value, psychopathy and sociopathy tend to be mentioned more and more frequently in daily and weekly magazines in which they are mostly perceived as common dysfunction of some people rather than a diagnosis that is often observed in criminal, imprisoned populations [4]. Many researchers have pointed out that APD is very common among criminals and this is the reason why most studies have been conducted in these populations [5]. However, this popular notion that some traits of psychopathy can be found in 641 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) a non-institutionalized and non-criminal group of people is gaining ground very fast. Although this growing interest remained, until recently, only on a theoretical level, during the last decade many studies have been conducted in order to investigate how often psychopathic traits can be found among general population [3]. Psychopathy in General Population The idea that specific traits of psychopathy can be found in the general population has begun by some researchers who argued that psychopathy is a dimensional construct [4]. Self-report measures (e.g. the Psychopathy ChecklistRevised; Hare, 1991/2003) and data from randomized population samples have provided a first understanding of the way in which these traits exist, distribute and characterize almost 1% of general population [6-8]. In addition, the use of standardized psychometric tools that yielded reliable and valid statistics provided further support in these large-community studies [9]. For example, Weiler and Widom [10] found that individuals with a history of child abuse had much higher scores in self-report measurements of psychopathic traits than those who were not victims of abuse. Furthermore, these researchers observed that abused individuals had a history of adult violence in comparison to the other group of participants. Farrington [11] also observed in his longitudinal study that few people with no history of child abuse and violence in adulthood tend to be more irresponsible, impulsive, deceitful and manipulative than others. In order to expand this observation, he tried to correlate his findings with many socio-demographic variables such as gender, age, family status, family background, occupation, educational level and income. After analyzing these data, he found that a significant proportion of single, middle-aged, highly-educated and professionally successful (as measured by their income) males identified to have significantly more psychopathic traits in comparison to other groups of participants. Based on these interesting findings, it was concluded that few individuals may put themselves above others in order to achieve any professional and/ Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? or academic goal and this particular behavior may be guided by some specific personality traits such as egocentricity, manipulation of others, superficial charm and pathological lying [11]. However, the study of Farrington [11] may be criticized because it was used a self-report psychopathy scale that was only theoretically related to psychopathy. To be more specific, although the researcher has chosen a reliable and valid tool in order to make measurements, this tool was chosen only on the basis of a theoretical model which conceptualizes the dimension of psychopathy as a social construct and not as a global trait. Although this study had practical and theoretical implications, the use of clinical rating scales combined with structural clinical interviews would had provided further support to these findings. Apart from that, in the study conducted by Weiler and Widom [10] the sample was consisted of paid volunteers who, (after a follow-up evaluation by another research team), almost half of them were seeing themselves as charming, impulsive, sensation-seekers, and risktakers. Although these participants had higher psychopathy scores and expressed more often violent behaviors, the high percentage of those who at baseline described themselves with the above-mentioned traits should had be taken under strong consideration, since it introduces the possibility of selection bias. All things considered, it should be kept in mind that these studies used self-report measures of psychopathy that in many cases their lack of accuracy in capturing real tendencies may be a major problem [12]. However, other quantitative studies with more complex methodological designs (which are not simply observational) have been conducted in order to help scientists coming up to more solid conclusions. These studies went beyond the simple investigation of psychopathy in relation to its early indicators (such as abuse), future outcomes (such as risk of violence) and sociodemographic characteristics. They are mainly focused on the association between psychopathy and various skills (that can affect significantly various aspects of individuals’ life) such as moral judgment, decision-making, problem-solving, rational thinking and leadership. Some of these studies have tried to answer the question of what it takes for someone in order to become a leader. Problem-solving skills, rationality and the ability of making difficult decisions may be some of the core features that a leader should have [2]. Therefore, these features can be viewed as sub- Review skills of leadership. Although there are some important confounding factors such as IQ and emotional intelligence [13] that may also be related to leadership due to the fact that both of them contribute positively on the development of the above-mentioned sub-skills, in the case of psychopathy-leadership relationship there is no a definite answer yet. Leadership in Business Before reviewing the recent research literature in an attempt to explore if there is any relationship between psychopathy and leadership, it is important to define leadership first and investigate some of the key personality characteristics that leaders usually have. Leaving psychopathy aside for now, many researchers (e.g. [14,15]) have argued that a great leader should have a vision, an ability to inspire others, a high sense of commitment towards organizational goals as well as a high intellectual development. As Chemers [16] has argued: “leadership is the process of social influence in which one person can enlist the aid and support of others in the accomplishment of a common task”. At this point, it should be noted that leadership behaviors are very difficult to be investigated in the workplace using self-report questionnaires because managers and chief executive officers (CEOs) are usually very busy people and their willingness to participate in this type of study is always very limited [17]. Specifically, by being interested mostly in the growth of their business, personal success, money, and power, these people usually care little about a study that attempts to reveal some aspects of their personality [17]. Thus, most theoretical attempts of defining leadership and attributing specific characteristics on it are only a way to explain how specific leadership skills result in an organization’s success. There are different types of leadership which amongst them the most well-known are transactional and transformational leadership [18]. Transactional leadership refers to the interaction between active leaders and satisfied employees. More specifically, leaders who create a reward system and through this reinforce their employees (e.g. with pays, promotions, positive feedback etc.) when objectives are met, manage to increase the productivity of the organization and grow their business. In this type of leadership, successful leaders are those who have the following characteristics: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individual consideration. The first two 642 Review Georgios Kountouras compose the idea of “charismatic” leader while the last two constitute the “smart” leader [18]. On the other hand, although transformational leaders create also a developmental environment that encourages employees’ productivity, they act more as role models and ideals without trying actively to inspire or encourage them [18]. The major difference between these two basic leadership types is that the first one is focused more on employees’ abilities and skills while the second one is concerned especially with personal development issues that perhaps promote more directly leadership success [18]. Lastly, there is also a third type of leader which has not received much attention, indicating that it is rarer than the other two. Avoidant/passive leaders do not take action until mistakes are noticed and problems emerge on the surface. They are unwilling to accept the responsibilities of their actions, and they are not often present when needed [19]. Psychopathy and Leadership Some theorists (e.g. [20]), during the past few years, have proposed a fourth leadership style – the so-called “psychopathic leadership”. Babiak and Hare [2] have found that 3.5% of the business world has specific psychopathic traits such as grandiose sense of self-worth, superficial charm, lack of empathy, shallow affect, manipulation of others and pathological lying. Added to this, three organizational psychologists, Cangemi, Joseph and Pfohl [13] who have worked in the HR department of many business organizations, have questioned the accuracy of these percentages by pointing out that the percentage of psychopathy in the business community is much higher. Basically, the idea behind psychopathic leadership style is that some people present the above-mentioned sub-clinical traits of psychopathy, and thus they often manage to rise rapidly through the organizational ranks into higher managerial positions that give them power and control over others [21]. At this point, it should be noted that the term “subclinical psychopathic traits” means that these traits are not severe enough in order to decrease individuals’ social, occupational and cognitive functioning. Moreover, the required criteria for the diagnosis of APD are not met not only in quality, but also in quantity as APD requires a diagnosis of conduct disorder before the age of 15 years, and a past criminal record, usually of minor offences [22]. Babiak, Neumann and Hare [22] have argued that psychopathic leaders are benefited by the 643 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) way in which business industry operates. More specifically, psychopathic leaders, by being able to satisfy their needs for excitement, and by having the opportunity to demonstrate their charm in this chaotic work environment, they are able to adequately cover their unorthodox leadership style often characterized by the manipulation of other people, deceitfulness and abuse of power. Added to this, the fact that they are not compelled to obey in any structured rule setting combined with their unlimited authority, the strict control that they have on the circulation of information and reward systems, makes them able not only to survive but in most cases to thrive in many business organizations [23,24]. The theoretical model that supports the association between psychopathy and leadership had emerged from the conceptual framework of social constructivism. In simple terms, Pech and Slade [25] suggest that psychopathic leaders are successful in business organizations because of cultural and structural-based meanings that society attributes to ideal leaders. Western cultures that favor manipulative, egocentric, and self-centered managerial behavior are more likely to operate more efficiently by having such leaders under the wheel. Furthermore, considering the fact that these CEOs are usually delivering to, and meeting the organization’s goals and expectations, an extra focus on some of their negative aspects of their personality may be overlooked [2]. For the purpose of this current systematic review, an analysis of any positive and/or negative impact of psychopathic leadership style on business industry will not be made. Instead, the author will try to explore in depth a possible association between psychopathy and leadership, provide a rationale for studying this topic, and evaluate all the known empirical evidence that support or put in question this particular association occurred in business settings. Therefore, this review should be seen in the context of a possible correlational relationship between psychopathy and leadership that will not imply causality at any stage of analysis. Corporate Psychopaths: Research Literature Review The literature contains many theoretical attempts of justifying the psychopathy-leadership association. In brief, theorists (e.g. [26,27]) believe that most people with sub-clinical psychopathic traits are attracted by the glamour of the business world because by working in this Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? setting they satisfy their need for admiration that usually seeks from others. Moreover, working in such settings is a good way to conceal the dark side of their personality by being superficially charm and look “normal” [2]. However, all these perspectives are good in theory but they are not telling much about corporate psychopaths. It is true that studies which used a sample of corporate psychopaths in order to determine how often psychopathy is observed in this type of leaders are very limited. One of the well-validated studies on the field of organizational psychology was made by Board and Fritzon [28] who analyzed the profiles of CEOs’ personalities in order to compare them to imprisoned and institutionalized individuals. This studies had a sample consisted of 36 CEOs, 768 mental health patients, and 317 imprisoned individuals with a psychiatric classification of antisocial personality disorder. The assessment method used to make measurements in the three groups of participants was exactly the same. More specifically, personality profiles data across all groups of participants were collected using the Morey, Blashfield, Webb, and Jewell screening tool. This tool contains different scales that some of them are also included in the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, and they are designed to assess features of psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder. Based on this study’s findings, CEOs had significantly higher scores on the histrionic personality disorder scale (that includes items which measure superficial charm, manipulation of others and deceitfulness) than both mental health patients and imprisoned individuals. CEOs’ scores were also higher than both comparison groups on the narcissistic personality disorder scale (that includes items which measure admiration seeking, grandiose ideas and a tendency to put you above others). The interpretation of these findings by Board and Fritzon [28] was that psychopathic personality traits are much more evident in individuals that are on the top of the organizational ranks than in mental health patients and criminal population. Nevertheless, this study should be criticized for several reasons. Firstly, the assumption that psychopathic leaders have histrionic and narcissistic traits has not been confirmed yet. To support that, although Torgersen, et al. [29] have observed that there may be an overlap between psychopathic, narcissistic and histrionic personality, this particular overlap has not Review been seen empirically many times. Secondly, researchers did not use a direct measure of psychopathy but they measure it indirectly through histrionic and narcissistic scales. Thus, due to the fact that it was not used a pure measure of psychopathy (e.g., the PCL-R; Hare, 1991/2003) across all group of participants, the real number of individuals that would have met the criteria of psychopathy is basically unknown. Above all these minor criticisms, this study’s results have been widely cited as wellsupported evidence for an increased prevalence of sub-clinical psychopathic traits in CEOs (e.g.,[30,31]). Consistent with these findings, Babiak and Hare [2] found that six of 200 high-profile chief executives in the highest organizational ranks (3.5%) were identified with specific psychopathic traits. Before arguing that this percentage seems to be quite small, it should be firstly considered that the estimation of psychopathy in the general population is between 1 to 3% of the adult male and 0.5 to 1% of the adult female populations [2]. All of the CEOs were presented with traits of primary psychopathy such as superficial charm, grandiose ideas, pathological lying, impulsiveness, irresponsibility, callousness, absence of remorse and lack of empathy [2]. Babiak and Hare [2] concluded that there may be an overlap between leadership and primary psychopathic traits by pointing out that “a charming facade and a grandiose talk can easily be mistaken for charismatic leadership and selfconfidence” [2]. However, this study was presented only in the book “Snakes in Suits: When Psychopaths go to work” written in 2006 by these two published experts in the fields of psychopathy and organizational psychology, respectively. A detailed description of the method, results and discussion sections was not given in order for the author to appraise the study appropriately. Thus, it was decided not to be included in the final list of papers for this systematic review, despite its close relevance. In another study conducted by Babiak, Neumann and Hare [22], it was examined psychopathy in a convenience sample of 203 individuals with top managerial positions and found a higher incidence of psychopaths in leader positions than would be expected among the general population. From the 203 CEOs who were participating in this large study, nine (4.4%) had very high psychopathy scores and six (3%) 644 Review Georgios Kountouras scored highly enough to qualify as psychopaths on the psychopathy scale. This finding suggests that these individuals may have some of the subclinical traits of psychopathy and provides further support to the argument that these traits are often become evident on individuals who have leadership positions. Researchers went beyond the psychopathy-leadership association and tried to specify the particular subtype of psychopathy that characterizes corporate psychopaths. They found that from the group of psychopathic CEOs, all of them had the primary subtype of psychopathy characterized by arrogance, callousness, and manipulative behavior. This observation was consistent with Babiak and Hart [2] argument that some of the traits found commonly in leaders, such as persuasiveness, charisma, risk taking, determination, and calmness under pressure, correlated highly with the primary type of psychopathy. In the contrary, the secondary type of psychopathy includes antisocial traits and impulsive traits that are usually seen in forensic settings [32-34]. Finally, in another study conducted by Boddy, Ladyshewsky and Galvin [35] was showed that the number of managers with higher positions in an organization who found to have some of the primary subclinical psychopathic traits is significantly larger compared to the number of lower level employees. This evidence also showed that not every individual that works in a business setting can be potentially identified with these traits. However, this may be true for the majority of individuals with leadership positions. All things considered, there are an extremely limited number of studies that investigated the association of psychopathy and leadership using a pure sample of senior managers or CEOs working in large organizations. For the purpose of this review, the first two studies of Board and Fritzon [28] and Babiak, Neumann and Hare [22] respectively were considered to be suitable, and thus they were included in the part of analysis and evaluation. The study conducted by Boddy, Ladyshewsky and Galvin [35] was excluded since it did not use a sample of senior managers/CEOs, but 346 employees of them who were asked to evaluate their bosses. Overall, for the purpose of this review, the author used four studies that met the basic aim and inclusion criteria that had been set before searching the research literature. The rest two case studies included in this review will be mentioned briefly in the study’s rationale section. 645 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) Rationale Although there is a growing research interest on personality-leadership association, most of studies that included a trait approach to leadership [3641] has focused especially on Big Five Factor Model, and not on psychopathic traits. Added to this, not only there is an extremely limited number of studies on psychopathy-leadership association that have used a sample of senior managers/CEOs, but also since to the author’s best knowledge there has not been conducted any other systematic review on this topic before. Therefore, there is not only a great need for more research focusing on psychopathy-leadership association, but also a much greater need for a systematic review that summarizes, analyzes and evaluates the existed findings in order to provide the first conclusive evidence that either support or refute this association. For this reason, this systematic review is a novel piece of work as it will provide a further insight into the factors (which amongst them perhaps the most crucial and not well-studied is psychopathy) that contribute on the rise of some individuals in leadership positions. Prior research literature (e.g.[10,11] ) that has tried to link psychopathy to general population suggested that this relationship may be by far clearer than the association between psychopathy and various skills such as leadership [2]. This may be true considering the fact that it is much easier to choose a population sample by following the basic randomization techniques and then study the prevalence of psychopathy on it in relation to some socio-demographic variables. However, the case is completely different when the sample is high executive managers with heavy workload, high-prioritized responsibilities and a possible unwillingness to participate in this type of study. This difficulty in approaching them has urged most of researchers to study psychopathic leadership through employees’ attitudes toward their bosses. Other studies have used a sample of corporate employees and/or business students with some management experience in an employment setting in order to investigate either their evaluations on their managers’/CEOs leadership style or how many of them expressed leadership behavior and could be also identified with psychopathic traits, respectively. However, these studies (e.g. [18,35,42-45]) might not able to capture the true psychopathy-leadership association since they relied either on third party Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? information provided by employees that did not work closely with their senior managers/CEOs or on non-representative samples of business undergraduates. For example, employees’ evaluations on senior managers’ leadership style (that know little about them) may be guided by their personal prejudices, subjective opinions and hostile feelings towards their bosses. Also, undergraduate students are usually not longterm and well-proven leaders with many years of experience in business settings, and therefore the psychopathic leadership style that characterized them may be circumstantial. Considering all these issues, it is easy to understand why there is a further need to conduct a systematic review that will include the rarest and most well-validated studies with data obtained (via observational and interview procedures) either by middle managers working alongside their bosses (e.g.[46,47]), or directly from difficult-to-approach samples of senior mangers/CEOs (e.g.[22,28]). In this systematic review, the author included four original studies [22,28,46,47] that investigated if individuals working in big organizations and having leadership positions could be identified with the sub-clinical traits of primary psychopathy. In Babiak’s [46] longitudinal case study, it was found that a newly-hired employee named Dave who was identified with psychopathic traits, managed to get a promotion in his department and finally gain a higher position despite his constant conflicts with the senior manager of the department. Boddy [47] in his longitudinal case study, examined the case of a corporate psychopath CEO based on an interview taken from one senior manager and one middle manager who were working alongside him. Psychopathic CEO was found to be superficially charming, fearless, untruthful, deceitful, egocentric, remorseless, callous, interpersonally unresponsive, irresponsible and lacking in self-blame. In the first case study, it was concluded that psychopathic traits perhaps help an individual to reach a higher organizational rank. Based on the findings of Boddy’s [47] case study, it was hypothesized that an individual in a leadership position is quite possible to be identified with subclinical psychopathy. Aims and Objectives The basic aim of this systematic review was to find out if there was any association between the core primary psychopathic traits and leadership positions in business settings. For that reason, the author collected, summarized, analyzed Review and critically appraised all the quantitative and qualitative data obtained by the above-mentioned four studies. Thus, the main objectives of this systematic review were: To identify all studies that investigated the subclinical traits of primary psychopathy in individuals with leadership positions in business settings. • To assess the quality of these studies. • To determine if primary psychopathy is related to leadership in business settings. • To identify gaps in knowledge where new studies in this area are needed. Systematic Review Methods Search Strategy Literature Search: In order to search for existing reviews and primary studies consistent with the review’s objectives, a search of electronic databases (PsychINFO, PubMed, Scopus and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews) was carried out on 23.07.16 using the following terms: “psychopathy” AND “leadership” AND “business settings”. Search Engines: Studies were systematically identified by searching electronic medical and psychological literature databases. The following databases were searched from inception/1966 to October 2016: PubMed (1996 to October 2016), PsychINFO, Proquest (for unpublished dissertations), Dissertations and Abstracts, Academic Search Premier, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), and Scopus (1966 to October 2016). These searches were made between July 2016 and October 2016. For the purpose of this project, the author started looking for documents published ten years before the current project plus any classic document related to this particular topic which it is usually standard in systematic reviews. No limit was placed on date of publication due to scarcity of relevant studies. Additional databases were searched, including Index to Theses, and Google Scholar. Personal Contacts :Leading experts in the fields of leadership, organizational behavior and psychopathy such as Professor Clive Boddy, Professor Robert Hare and Dr Paul Babiak were contacted via e-mail and were asked to provide further information for published and unpublished work in this particular area 646 Review Georgios Kountouras of interest as well as for assistance in locating possible studies conducted internationally. Hand Searching : The Journal of Applied Psychology (publication dates 1998-2016), the International Journal of Law and Psychiatry (publication dates 2009-2016), The European Journal of Personality (publication dates 1995-2016), and the British Journal of Psychiatry (publication dates 1998-2016) were hand-searched as they were likely to contain information relevant to the population under investigation (non-criminal, successful psychopaths), were known to contain information relevant to the phenomenon under investigation (psychopathic leadership), and in an attempt to locate an international crosssection of studies. No relevant papers were retrieved during this search. Reference lists: Reference lists of studies found relevant for this review as well as related studies were examined for sources of further relevant data. This investigation resulted on the retrieval of one case study [46] that was included in this review. Search Terms and Results: The author conducted the main search on the psychopathyleadership relationship in two stages. In the first place, the keywords “psychopathy” AND “leadership” were entered in the Scopus database. The search resulted in 60 documents. Accordingly, the author searched the PubMed, PsychINFO, and Google Scholar databases using the terms of “leadership”, AND “psychopathy” OR “psychopathic traits”. This search in these databases did not result in any relevant papers for this review. To be more specific, business and psychiatric subject headings and text-word terms were combined in the main search strategy that it was developed by the author. Business terms used for search purposes were “leadership”, OR “leadership positions”, OR “managerial positions” AND “CEOs”, OR “senior managers”. Psychiatric terms were the following: “psychopathy”, OR “sub-clinical psychopathy” OR “primary psychopathic traits”, OR “psychopathic leadership”. This search strategy was modified and both business and psychiatric terms were combined appropriately for use in each of the above-mentioned databases. In order to maximize sensitivity the author did not add any additional terms for study design. However, there was a restriction for searching papers only on the English language. All references were downloaded into Mendeley Desktop, version 1.16.3 developed by Elsevier in 2008. 647 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) Selection of Papers Abstract Appraisal: Titles and abstracts of published articles identified by the searches were assessed for potential inclusion by the author of this review. Primary studies in the field of business and organizational psychology that included both psychopathy and leadership were considered potentially eligible. Full, peerreviewed articles that investigated if there was any association between primary sub-clinical traits of psychopathy and leadership in business settings were included. Non-peer reviewed articles (e.g. conference abstracts and dissertations) were not found by the author because the topic of this review is completely new. Studies available only as abstracts were not included because all of them did not contain sufficient information about studies design, population samples, data collection and detailed descriptions of results. Any reference that was considered for inclusion by the author was retrieved for full paper inclusion assessment. Inclusion Criteria: Full-completed studies that met the following criteria (Table 1 for a brief summary) were decided by the author to be included in this review. More specifically, the author decided to include: Primary studies of any design, although the appropriate study designs for this type of research are observational, longitudinal, cross-sectional and case series, not ecological, case-control or randomized-controlled trials. Primary studies that included as a sample middle/ senior managers or CEOS. Primary studies that collected data either directly from middle/senior managers or CEOs or indirectly by a high-ranking individual worked alongside them. Primary studies that one of their main objectives was to investigate psychopathic leadership in business settings and no other leadership positions and styles or personality types (e.g. Machiavellians). Primary studies in which researchers assessed psychopathy through standardized clinical construct raring scales (e.g. PCL-R; [8]), widely used standardized and well-validated self-report questionnaires (MMPI) as well as through observational - interview methods. Primary studies wherein the psychopathy measure was a combination of more than one trait or multiple sub-dimensions (e.g.[28]). Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? Primary studies that perceived leadership as the result of a successful career movement in the top organizational ranks of a company. Table 1: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. Exclusion Criteria: In the current review, the author decided to exclude studies in which psychopathy and leadership were not in reference to the same person (i.e., several studies reported a correlation between employees’ attitudes, job satisfaction or well-being and psychopathic leadership behaviors), studies of leadership that were specific to a particularistic criterion (e.g., political leadership), studies without data (e.g., literature reviews or theoretical works), and studies that have not been fully completed yet. Finally, the author excluded studies that operationalized leadership as elected positions held in other work environments such as high schools or Universities, military job positions, or persons most liked by peers (which they are often perceived as “leaders”). Collection of data Therefore, from the initial number of 60 papers (Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram) identified in the main database and after excluding 27 papers that investigated both Machiavellians, Narcissists and Psychopaths (the so-called “Dark Triad”) that held leadership positions in various settings, 14 papers that were focused only on the destructive leadership style of corporate psychopaths, 10 papers that were only theoretical and literature reviews, and 6 papers that obtained data from large samples of employees and not from middle/senior managers or CEOs, the author came up to the final number of 4 original studies (including Babiak’s case study published in 1995 that was retrieved through a reference list searching). These four papers either investigated some specific traits of corporate psychopathy in relation to business leadership or they were focused on the psychopathy-leadership association in general. This association was specified in these studies in terms of how often psychopathy was presented on individuals that either held top managerial positions in big companies or managed to rise rapidly through the organizational ranks into higher managerial positions. Data Collection and Analysis Data Extraction Methods A data extraction sheet was specifically designed and employed to systematically extract data from the four studies included in this review. Parameters Sample Transcript Predictor Variable Outcome Variable Psychopathic Leadership Inclusion CEOs, senior/middle managers Clinical Rating Scales, MMPI, Interviews Full transcript with data Sub-clinical psychopathic traits Leadership in business settings With reference to the same person Review Exclusion Low-level Employees Self-report measures only No transcript available Other personality types Leadership in various settings Attitudes towards CEOs/ managers only More specifically, data extracted included the following main aspects of each study: a) sample size, b) target group (CEOs or senior/ middle managers), b) scores on the clinical rating and MMPI scales of psychopathy, c) interview outcomes, d) duration of observing participant/s in their workplace (if applicable), socio-demographic outcomes measurements (gender, age, family status, educational level, years of work experience, job position etc.) and results. The author was not blinded to the names of study authors, organizations or publications. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies Quality assessment of the two quantitative crosssectional studies ([22,28]) was performed by the “Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies” (QATQS) developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) in 1998. This standardized and well-validated assessment tool (kappa=.71; [48]) was developed in order to provide high quality systematic reviews that include studies of many methodological designs, including the cross-sectional one. Results of the QATQS lead to an overall methodological rating of strong, moderate or weak study in eight sections including 1) selection bias, 2) study design, 3) confounders, 4) blinding 5) data collection methods, 6) withdrawals and dropouts 7) intervention integrity and 8) analysis. QATQS has been used widely for the evaluation of crosssectional, longitudinal, observational and cohort analytic, case-control and RCTs study designs ([49]), and thus the author decided to use it in this review (Appendix 1 for the QATQS quality assessment form). Risk of bias for the rest two case studies [46,47] was assessed by the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Series (Appendix 1) quality assessment tool developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute in 2016. The purpose of this tool is to assess the methodological quality of a study and 648 Review Georgios Kountouras Figure 1: PRISMA Flow diagram. to determine the extent to which a case study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis. The rating scale is a fourLikert type one including answers of “yes”, “no”, “unclear” and not “applicable” to questions related to the design, conduct and analysis of a case study. The results of this assessment can be used to inform synthesis and interpretation of the overall study results. Although this recently developed tool has not been widely used, it 649 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) is approved by the JBI Scientific Committee following extensive peer review. To eliminate the risk of the reviewer’s bias [49], the above-mentioned tools were both completed by two raters. One of them was obviously the author of this review while the second one was an experienced research psychologist that holds an MBA Global. The kappa coefficient which indicated the strength of agreement between these two raters was calculated for both QATQS Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? and JBI used to assess the methodological quality of the four studies. To calculate the kappa statistic (Appendix 2 for the SPSS output), the author used the SPSS statistical software version 17.0. Methods of analysis A meta-analysis was not undertaken due to the diverse samples, measured outcomes, and methods of assessing corporate psychopathy. Based on the Cochrane Handbook of systematic reviews, an analysis of data that were obtained through different methods often leads to unrealistic results [50]. Thus, the diversity in samples, methods, and outcome measures should be firstly considered by each author when a decision of conducting a meta-analysis is going to be made [50]. Results Characteristics of included studies Of the four studies included in this review, two were case studies ([46,47]) and two had a cross-sectional study design [22,28]. PCL-SV [51] and PCL-R [8] were the rating scales used for assessing psychopathy in two of the four studies. MPPI for Personality Disorders was the only self-report tool that was used to assess psychopathy in the study of Board and Fritzon [28]. The “Psychopathy Measure-Management Research Version 2” (PM-MRV2) was used in the case study of Boddy [47] as a checklist tool that contains 10 different characteristics of psychopathy. All 4 studies included as a sample individuals with higher/highest managerial positions or presidents, vice presidents and CEOs. Exception is the case study conducted by Babiak [46] in which a newly hired employee managed to get in a relatively short period of time a managerial position. All studies found that individuals who held (or managed to get) these leadership positions had also high scores on psychopathy scales. One study [28] included also comparison groups (mental health patients and prisoners). In the study of Babiak, Neumann and Hare [22] there were made inner group comparisons on individuals’ psychopathic scores with regards to the job position that they held (middle/senior managers vs. CEOs). Finally, in the case study conducted by Boddy [47], the current CEO of a company was found to have a much higher score on psychopathy compared to the former one. The above-mentioned characteristics are summarized and presented in Table 2. Review For clarification purposes, the four studies included in this review were categorized into two main groups based on their study design. The first group consists of Cross-sectional Studies while the second group consists of Case Studies. Cross-sectional Studies There were two cross-sectional studies identified for the purpose of this review and originated from United States and United Kingdom, respectively. A cross-sectional study design is a type of observational study that analyses data taken from a population or a representative subgroup of it at a specific period of time [52]. Cross-sectional studies are descriptive studies that are often useful for researchers who want to describe a feature of the population such as the prevalence of a disorder [52]. The two cross-sectional studies [22,28] included in this review had both of them a target group of business managers and chief executives that held leadership positions within their organizations and attempted to estimate the percentage of psychopathy in it. In the study of Board and Fritzon [28], the original sample size was consisted of 39 males business managers and chief executives (who had leadership roles for at least 20 months) working in leading British companies. The comparison groups were 475 randomly selected psychiatric patients and 1085 mentally disordered offenders from Broadmoor Special Hospital that Table 2: Summary of characteristics for each study separately. Country United Sates United Kingdom Characteristics Design Cross-sectional Case study Sample Managers CEOs Presidents Vice Presidents MI Patients MI Offenders Tools PCL-SV PCL-R MMPI-PD PM-MRV2 Outcome Psychopathic leaders √ Babiak (1995) √ √ Board & Fritzon (2005) Babiak, et al (2010) √ √ Boddy (2015) √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ 650 Review Georgios Kountouras subdivided in two subgroups; 768 offenders with any type of mental illness and 317 offenders with a diagnosis of psychopathic personality disorder. Data from these comparison groups were selected retrospectively. These groups were matched for sex and thus comparisons were made only between males. The authors used the MMPI for Personality Disorders which has 11 scales with 38 items and it is a true/false self-report questionnaire that was developed by extracting 162 items from the item pool of the MMPI. Each “true” item is rated with 1 point while each “false” item is rated with 0 point. Thus, the higher the score on any scale the more indicative it is of the PD criterion it represents. Results showed that the group of senior managers and CEOs had a significantly higher MMPI-PD score on histrionic scale (that includes psychopathic traits such as superficial charm, manipulation of others and egocentricity) compared to the other three groups. This difference was even larger between the corporate sample and the two sub-groups of mentally disordered offenders. The corporate sample scored higher also in the narcissistic and compulsive scales, but the results were not statistically significant. However, in the other scales which are generally associated with criminality and delinquent behavior (antisocial, passive-aggressive, paranoid and borderline scale), senior managers and CEOs had significantly lower scores compared to other 3 groups. The authors concluded that primary subclinical psychopathic traits (such as superficial charm, egocentricity, manipulation of others, grandiosity, lack of empathy, pathological lying, independence, perfectionism, excessive devotion to work, rigidity, stubbornness, and dictatorial tendencies) may be presented in a sample of business managers and CEOs (that have leadership roles) significantly more often than in the psychiatric and/or imprisoned population. In addition, they concluded that the absence of secondary psychopathy characterized by a social deviant lifestyle (e.g. impulsivity, hostility, physical aggression) may be one of the reasons behind the successful career movement of corporate psychopaths into leadership positions. The study of Babiak, Neumann and Hare [22] had the largest sample size of all of the included studies as it was consisted of 203 managers and executives working in the largest US organizations. This large sample was selected from management development (MD) programs that were designed for each of the 651 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) respective companies. Individuals were chosen to participate in these programs based on their companies’ belief that they had managerial and leadership potential. Measurements were made with the PCL-R [8] which is a 20-item clinical construct rating scale that uses a semi-structured interview, case-history information, and specific scoring criteria to rate each item on a three-point scale (0, 1, 2) according to the extent to which it applies to a given person. Total scores of PCL-R are ranged from 0 to 40. PCL-R identifies many psychopathic traits such as superficial charm, grandiose sense of self-worth, pathological lying, lack of remorse and guilt, shallow affect, manipulation of others, impulsivity and parasitic lifestyle. Scores on these sub-scales for each participant were calculated after face-to-face meetings, observations of social and work-teams interactions as well as meetings with participants’ supervisors and colleagues. An overall assessment of individuals’ performance who participated in these management programs including communication skills, leadership skills, strategic thinking, management style, creativity and being team player were made and the outcome was correlated to the PCL-R scores. Results showed that although there was not a significant association between the management position (and the level of it) that an individual held within the organization and scores on psychopathy, nine participants who had a PCL-R score of 25 or above (which is considered very high; Hare, 1991/2003), were also in the highest organizational positions (e.g. presidents, vice presidents, CEOs). Moreover, high scores on PCL-R psychopathic scales were positively related to communication skills, strategic thinking, and creativity, but negatively related to being a team player, having leadership skills and being a good manager. The authors concluded (after comparing the PCL-R scores of this corporate sample to those taken from a community sample of a past study) that psychopathy was not associated with participants’ age, gender and education as well as that business managers and CEOs had a significantly higher PCL-R score compared to the community sample. It was also stated that although these managers and CEOs were presented with a lack of leadership and management skills after their performance assessment in MD programs, the fact that they were perceived as having leadership potential by their companies (despite that this was found to be unrelated to PCL-R scores) and being rated with good communication skills, creativity and Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? strategic thinking by their subordinates gave them the opportunity to promote their careers through high ranking leadership positions. Socio-demographic information about these two cross-sectional studies sample size, mean of age, job position, educational level and marital status are summarized in Table 3 below. Detailed numerical results consistent are presented in Table 4 and 5, respectively. Information about participants’ marital status in Babiak, Neumann and Hare’s [22] study was not collected due to the fact that the sociodemographic forms were designed specifically for the MD programs which had some particular restrictions on their content. Similarly, the Board and Fritzon’s [28] study did not include further information about participants’ race and therefore it can be assumed that all of them were Caucasian males. Case Studies There were two case studies identified for the purpose of this review and originated from United States and United Kingdom, respectively. A case study is a type of study that analyzes holistically a person, an event, a group or a situation by using one or more methods over a sustained period of time [52]. According to the most commonly agreed approach among researchers, a case study can be defined as a research strategy that investigates empirically a phenomenon within its real-life context [52]. The case study research can include single and multiple cases, can include quantitative evidence, relies on multiple sources of evidence, and often derives from an existed theoretical perspective that tries to explain a particular phenomenon or behavior [52]. Thus, a case study research can be based on any mix of quantitative and qualitative data and it should not be confused with quantitative studies [52]. Each one case study [46,47] included in this review focused on one individual working in a big business organization and assessed him using a holistic approach for a sustained period of time in an attempt to explain his behavior and draw some relevant conclusions about it. In Babiak’s [46] case study, the participant named Dave was a newly-hired employee that after a short period of time managed to rise rapidly into a higher managerial position despite the conflicts with his supervisor. Although Dave was described as an ambitious, creative and bright employee, he also described as rude, selfish, immature, self-centered, unreliable, Review Table 3: Socio-demographic Variables: Cross-Sectional Studies. Variables Sample size Males Females Race Caucasian Asian African-American Hispanic Mean of Age Marital Status Married Single In a relationship Divorced/Widowed Job Position Middle/senior managers/ directors CEOs/Presidents Vice presidents Other key staff/managers Education Basic only Higher Highest Comparison Groups Psychiatric Patients MI & PD Offenders Board & Fritzon (2005) 39 39 Babiak, et al (2010) 203 158 45 181 2 4 6 45.8 35.92 20 10 3 6 30 86 9 0 0 21 51 45 8 31 0 158 45 475 1085 Table 4: MMPI-PD Scores on the four Psychopathy Scales across all groups. MMPI-PD Histrionic Scale* Narcissistic Scale** Compulsive Scale** Antisocial Scale* Borderline Scale Dependent Scale Passive-Aggressive Scale Paranoid Scale Schizotypal Scale Schizoid Scale Avoidant Scale p<.0045*, NS** Corporate Sample 13.33 15.58 7.35 8.64 9.23 5.92 Psychiatric Patients 11.29 15.85 8.59 10.65 15.77 12.06 8.46 14.34 7.07 13.08 16.38 12.41 3.67 14.54 3.38 12.43 9.66 7.96 5.56 7.87 8.04 6.25 5.82 9.17 6.61 12.79 13.79 22.85 12.82 21.93 13.70 22.70 13.09 8.70 8.61 14.13 7.96 17.59 MI Offenders MI Offenders and irresponsible individual by his colleagues. The case of Dave’s problematic behavior was analyzed by the author due to the fact that he was working as an organizational psychologist in this company at the same time as Dave was working there. To assess Dave’s behavior, the author used the PCL-SV (Hare, 1994) which is a 12-item clinical rating tool which rates items in a 3-point scale (2=match, 1=partial match and 0=no match). This screening tool includes 652 Review Georgios Kountouras 12 different characteristics of psychopathy and the higher the score the more indicative is the presence of psychopathy in individuals under evaluation. Results showed that Dave had a high score on psychopathy which was calculated at 19 points when the mean PCL-SV total scores are ranged from 13 to 16 points in forensic nonpsychiatric imprisoned populations. The author concluded that Dave’s ability to manipulate others and deceive them combined with his good communication skills and persuasiveness gave him the opportunity to get a promotion and achieve a successful career movement in a higher managerial position. Finally, the author reported also PCL-SV scores for other two participants that displayed a problematic behavior similar to Dave’s one. According to the author, these analyses were made for comparison and behavioral pattern identification purposes. Numerical results for each individual separately are given in Table 6 below. The case study of Boddy [47] was based on third-party information provided mainly by a respondent who was the middle manager of a department and worked alongside the CEO of a charitable company in the UK. The researcher interviewed the respondent multiple times in order to be able to complete the “Psychopathy Measure-Management Research Version 2” (PMMRV2) which was the basic tool of psychopathy in this study. This 10-item tool asks a colleague of the participant (where the respondent is typically a current manager) to rate some aspects of the participant’s behavior related to psychopathy. To be more specific, the respondent is asked Table 5: Correlations of the PCL-R scores with overall assessments and performance appraisals. Performance Interpersonal Assessment Communication Skills .34*** Creative/Innovative .28*** Strategic Thinking .31*** Management Style -.48*** Team Player -.71*** Leadership Skills .06 Performance appraisal -.40*** p<.05*, p<.01**, p<.001*** Affective Lifestyle Antisocial Total .27** .24** .20* -.48 -.66*** -.06 -.40*** .20* .21* .15 -.46*** -.58*** -.15 -.40*** .33*** .27** .30*** -.49*** -.71*** .04 .41*** .23** .21* .10 -.36*** -.52*** -.22* - .42*** Table 6: PCL-SV scores for the three participants in Babiak’s (1995) case study. PCL-SV Dave Participant 2 Participant 3 Score 19 19 20.7 Range of the mean total PCL-SV scores is generally between 13-16 points. 653 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) whether the individual under investigation is initially charming, poised and calm, untruthful, deceitful, egocentric, remorseless, flat in affect, interpersonally unresponsive, irresponsible and lacking in self-blame. Results showed that the current CEO displayed all the 10 characteristics of psychopathy as well as that his leadership style was destructive and had a negative effect on employees’ attitudes towards him and on the company’s future in general. In addition, these findings also revealed that some psychopathic traits may contribute on having a leader role in the business industry through a top job position despite the possible lack of actual leadership skills (e.g. inspire, direct and motivate others, have a vision for the company, be supportive, etc.) needed for this particular position. Study Quality and Potential Sources of Bias As it was mentioned earlier in the Methods section, the author and a research psychologist with MBA Global, evaluated these studies on several quality criteria including selection bias, design, conduct, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and dropouts, intervention integrity and analysis. Besides some minor differences on the points given to the above sections, there was a mutual agreement during the rating process and the final outcome was not altered for both cross-sectional and case studies. Board and Fritzon’s (2005) study: The QATQS result regarding Board and Fritzon’s [28] study revealed that this particular study was weak for a number of reasons. First of all, the total number of participants (n=39) agreed to participate in this study was small. Although 51 participants were approached and gave their consent to participate, only 39 actually took part and the researchers did not provide any reason that could potentially explain these dropouts. As a result of this, the representativeness of the sample can be questioned. Moreover, the study design is a limitation of its own due to the fact that a cross-sectional study’s findings can be attributed to reverse causality. Added to this, there were important differences between the three groups prior to the measurement procedure. Psychiatric patients and mentally disordered offenders are not comparable samples due to the fact that they might have received a specific kind of treatment at some point of their life (e.g. during their hospitalization). Thus, the reader does Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? not know if they were in a full remission phase or in a stage of recovery when their data were collected. Moreover, all groups were matched only for sex and not for other socio-demographic variables such as education. Blinding is a process that eliminates the risk of bias usually in RCTs. Due to the type of research in this area of interest and considering the design of this study, both the assessors and participants were aware of the purpose of it. Finally, a significant advantage of this cross-sectional study was the fact that the researchers used a valid and reliable tool to make measurements as well as that they investigated the internal consistency of MMPI-PD in a completely new sample of business managers and executives in which it was shown to yield good statistics. Babiak, Neumann and Hare’s (2010) study: In Babiak, Neumann and Hare’s (2010) study 203 business managers and CEOs were selected through MD programs by different US companies. They were not randomly selected due to the fact that they were chosen as candidates with high managerial and leadership potential for the study aims. However, the sample size was the largest of all studies conducted in this field. From the sample of business managers and CEOs who agreed to participate in the study, all of them completed without drop-outs. Although in cross-sectional designs a possible relationship between exposure and outcome is usually correlational and not causal, considering the nature of this study it can be argued that its methodology was an appropriate one. All participants did not differ significantly across many socio-demographic variables (such as education, health status, race and marital status), and thus there were not important differences between them prior to the assessment. A singleblind procedure (participants were not aware of the study’s research question) was used. In this study, the authors used also a valid and reliable clinical rating scale (PCL-R) and thus the data collection procedure seems to be reliable. However, the rater was only one and thus this might have introduced the potential of the assessor’s bias. The assessment procedure was consistent across all participants as the data were collected with the same way. Overall, the agreed result of this study’s quality assessment was at the moderate level. Summarized results of the QATQS for both Board and Fritzon’s [28] and Babiak’s, et al. [22] studies are presented in Table 7. Review Babiak’s (1995) case study: This case study was included in the current review with a good overall appraisal score for a number of reasons. Firstly, psychopathy was measured in a standard and reliable way for the three participants included in this study with the use of PCL-SV tool (although the main focus was on Dave’s case). Secondly, follow-up results obtained from observations in participant’s workplace, face-to-face meetings with the participant and working groups, and personal interviews were clearly reported for all participants with their overall PCL-SV. However, sub-scores in each of the 12 items of Table 7: QATQS result for the two cross-sectional studies. QATQS Selection bias Very likely Somewhat likely Not likely Can’t tell Percentage of participation agreement 80-100% agreement 60-79% agreement Less that 60% agreement Not applicable Can’t tell Confounders (yes/no) Race Sex Marital status Age Socio-economic class Education Health status Pre-intervention score Blinding (yes/no) Single Double Data collection tools Reliable Valid Drop-outs (yes/no) 80-100% 60-79% Less than 60% Can’t tell MI & PD Offenders Intervention Integrity Consistency of the measurement (yes/ no) Contamination/Co-intervention Statistical Analysis Appropriate Not appropriate Weak*, Moderate**, Strong*** Board & Fritzon (2005)* Babiak, et al. (2010)** √ √ √ √ Yes No √ √ No Yes √ √ √ √ √ √ No Yes √ √ √ 654 Review Georgios Kountouras PCL-SV rating scale were not reported neither for Dave nor for the other two participants. Thus, the reader is not aware of the items in which participants scored higher and lower. Added to this, socio-demographic information were not fully reported for all participants-only Dave was presented as a mid-thirties, married employee with four kids and a degree from a large University. Any other demographic information about his company was not reported due to the nature of this study. According to Babiak [46] it was “a rapidly growing, highly profitable mid-western United States electronic products company”. Overall, the total score of the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for the Babiak’ [46] case study was consisted of five “yes”, one “no” and four “not applicable” ratings. Boddy’s (2015) case study: Boddy’s [47] case study used the PM-MRV2 checklist tool for the identification of CEO’s psychopathic traits, but the author did not report any information about its reliability and validity neither in business settings nor in other settings. However, the author asked from a second respondent (another middle manager who was working alongside the current CEO for two years) to rate again the psychopathic CEO and the result was exactly the same. Thus, it can be assumed that the findings are valid. Participant’s sociodemographic information and his company’s information were not mentioned in order to be secured the anonymity and confidentiality of both respondents’ personal information. However, the results of the PM-MRV2 were clearly reported. Overall, this study included in the present review with a good appraisal score consisted of four “yes”, one “no”, one “unclear” and four “not applicable” ratings. Summarized results of the JBI Critical Appraisal checklist tool for both Babiak’s [46] and Boddy’s [47] case studies are presented in Table 8. Discussion Summary of the main findings This systematic review summarizes the results of 4 studies that investigated the association of psychopathy and leadership in business settings. Results of the studies included in this review showed that individuals with higher/highest job positions in business settings were identified with traits of primary psychopathy. More specifically, the two cross-sectional studies [22,28] revealed that most of those with psychopathic traits 655 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) were high-ranking executives as well as that the corporate sample had a significantly higher score on psychopathy scales not only in comparison to imprisoned and mentally disordered samples [28], but also compared to a community sample too [22]. The study of Babiak, Neumann and Hare [22] also showed that those identified as psychopathic high-ranking individuals were perceived by their companies as creative, good strategic thinkers, and good communicators. In the contrary, negative appraisals on psychopathic individuals with leadership positions included poor management and leadership skills and failure to act as a team player did not seem to have a negative impact on their successful career movement into the highest organizational ranks. This finding is supported also by the fact that in spite of these poor reviews especially with regards to the lack of leadership skills, all companies participated in MD programs seemed to view these “corporate psychopaths” as having leadership potential. Consistent with this finding, the case study conducted by Babiak [46] was focused on a psychopathic individual named Dave that managed to get a manager position in a short period of time. Dave was a newly-hired employee characterized by good communication skills, an ability to manipulate others and a pathological tendency to lying. Dave was able to formulate social relationships with his co-workers, be nice and charming with them and eventually take advantage on them in order to achieve his personal goals and climb the corporate ladder. Most of his co-workers had contradictive opinions about him. Specifically, while they were describing him as ambitious, smart and creative employee, they also characterized him as aggressive, rude, selfish, immature, selfcentered, unreliable, and irresponsible person. Combining these two findings from the studies of Babiak [46] and Babiak, Neumann and Hare [22], it can be concluded that these charismatic and manipulative traits usually allow corporate psychopaths to have a “normal” social and professional functioning as well as that their manipulation skills, persuasiveness, aggressive self-promotion, and single-minded determination may help them rise quickly into the highest leadership positions within an organization [2]. Added to this, in the study of Boddy [47] it was found that the current CEO of a large company was highly psychopathic as well as that despite the lack of leadership skills (e.g. guide, inspire and Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? motivate others, have a vision for the company, be responsible etc.), this CEO had a leadership position by supervising a large number of employees who they perceived him as “bad leader” and as a certain threat of the company’s future. Although one of the aims of this review was not to investigate the leadership style of corporate psychopaths, there is a pattern on this review’s findings that cannot be overlooked. Considering that the corporate sample of Babiak, Neumann and Hare’s [22] study included high-ranking psychopathic executives with lack of leadership skills and by analyzing the cases of Dave and psychopathic CEO in the two case studies of Babiak [46] and Boddy [47] respectively, it can be assumed that having a leadership position does not necessarily mean that the skills needed for someone in order to be a good leader are also present. Although good communication skills, charm, persuasiveness, and the ability to make rational, emotionless decisions would appear to benefit a company, it seems that corporate psychopaths are mainly self-serving opportunists. Therefore, these psychopathic traits seem to help these individuals get more easily what they want including money, personal success and power against their company’s interest. However, a further discussion on this destructive psychopathic leadership style would be beyond the scope of the current review. In addition, there is a common ground between the findings reported by Board and Fritzon [28] and those published by Babiak, Neumann and Hare [22] in terms of how often psychopathy is presented in senior managers/CEOs rather than in middle managers and other key staff of an organization. Specifically, these two studies showed that individuals who were at the top of their organizations’ hierarchy (presidents, vice presidents, CEOs) had significantly higher scores on psychopathy scales compared to those who were middle managers or supervisors of a department. This finding was more evident in the study of Babiak, Neumann and Hare [22] in which participants held either higher or highest job positions (e.g. middle managers, supervisors, senior managers, presidents, vice presidents, CEOs) within their organization rather than in Board and Fritzon’s [28] study which included only a small sample of 39 senior managers and CEOs. These findings are consistent with the current theoretical perspectives about psychopathy suggesting that the highly psychopathic individuals were more likely to be found at Review Table 8: The JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist result for the two case studies. JBI Babiak (1995)* Clear inclusion Criteria Yes No Unclear Not applicable √ Consistency of Measurement Yes √ No Unclear Not applicable Valid methods of data collection Yes √ No Unclear Not applicable Consecutive Inclusion Yes No Unclear Not applicable √ Complete Inclusion Yes No Unclear Not applicable √ Participants’ demographics Yes √ No Unclear Not applicable Participants’ clinical information Yes No Unclear Not applicable √ Clear follow-up results Yes √ No Unclear Not applicable Organizations’ demographics Yes No √ Unclear Not applicable Appropriate statistical analysis Yes √ No Unclear Not applicable Include*, Exclude**, Seek further info*** Boddy (2015)* √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ 656 Review Georgios Kountouras the highest job positions in a business setting in which they have better chances for gaining power, prestige and financial rewards [17]. This theory also suggests that these individuals are more motivated and determined in order to get this senior managerial positions that bring professional success because they mainly want to feel above others [2,17]. Therefore, it can be assumed that corporate psychopaths who held these specific positions in order to feel above others are sharing a common characteristic with criminal psychopaths who usually crave for power and control over their victims. However, as Board and Fritzon [28] have shown, corporate psychopaths share more differences than similarities with the criminal psychopaths with the latter ones being compulsive, irrational, antisocial, unplanned and emotionally unstable. It should be noted that the distinction between “successful” high-ranking psychopathic executives and “unsuccessful” criminal psychopaths is difficult to be made by simply arguing that there are two different types of psychopathy (primary psychopathy vs. secondary psychopathy). In brief, other sociodemographic (e.g. family background, economic class, socio-cultural context), biological and individualistic factors (e.g. IQ, pre-morbid personality, psychiatric history) that interact with each other may finally determine who will be in the boardroom and who will be in the prison. Finally, an interesting pattern of these findings is that in three [22,46,47] of the four studies included in this review, it was shown that despite corporate psychopaths’ poor performance at their workplace, they continued either to rise quickly at higher managerial positions [46] or maintained their top leadership positions for a long period of time [22,47]. In Babiak’s [46] study, Dave was found to be underproductive and often unreliable as he was often absent from group meetings. He was accused for using a plagiarized material and presented it as his own piece of work. However, Dave’s manipulation skills, persuasiveness and charisma helped him to establish strong social relationships with the president and vice president of the company, earn their sympathy, and finally become the manager of his ex-supervisor’s department. The psychopathic CEO in Boddy’s [47] study was also negatively appraised by his employees, but he continued to run his company despite the complaints, counter-productive work behavior and under-performance. This was also evident in 657 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) the large study of Babiak, Neumann and Hare [22] in which managers with high psychopathic scores were rated with poor management style, lack of teamwork, and low performance ratings. One explanation of these common findings may be that psychopathic traits such as superficial charm, manipulation techniques and interpersonally charismatic skills that assisted these individuals in the first place in order to get employed may also help them to manage others’ feelings and maintain their leadership position despite their poor performance [2]. Another theoretical explanation derived from the field of social constructivism suggests that the current research in psychopathic leadership should perceive the whole corporation as a “psychopathic organism”. Specifically, according to Boddy [53], a corporation may operate as a psychopathic organism as it often engages in illegal activities and seeks out loopholes in the law to avoid taxes and regulations. If these corporations “behave” as the psychopathic individual does (without caring about the safety of others and with an inability to conform to social norms and laws), it may be logical to assume that a business setting is an environment in which a psychopathic leader can evolve, rise and finally thrive without restrictions. However, there are not empirical evidence that support this hypothesis and although few studies (e.g.[21]) have shown that some organizations (especially banks and other financial institutions) operate in this way, research on how corporate psychopaths choose a specific type of organization (or chosen by it) did not have come to solid conclusions yet [53]. In the following sections, a detailed description of the included studies’ and systematic review’s limitations followed by the strengths and weaknesses of the review’s methods is presented. Studies Limitations The main limitation of the studies included in this review was their methodological design. Although a randomized design was not feasible in this type of research, a cross-sectional study design used in Board and Fritzon’s [28] and Babiak, Neumann and Hare’s [22] studies has its weakness as it did not allow the author to establish a causal relationship between specific psychopathic traits and leadership in business settings. Moreover, the way in which the results of these two cross-sectional studies were presented may Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? be criticized due to the fact that the possibility of reverse causality cannot be overlooked. The hypothesis that specific psychopathic traits may assist an individual to occupy a leadership position is not in one-way direction. Considering the way in which most corporations operate in western societies, it can be assumed that high-ranking executives develop specific psychopathic traits in order to cope with the challenges of the business world. Therefore, in simple terms as Clarke [17] points out “the more successful businessman you are the more psychopathic person you need to be”. Although many personality theorists such as Gordon Allport, Raymond Cattell, and Hans Eysenck have commonly argued that a trait is a stable and unchangeable element of one’s personality that become evident usually before adulthood, they have also pointed out that there is not a limited number of traits that dominate the whole personality as well as that specific traits are often appear only in certain situations or under specific circumstances [54]. Therefore, these sub-clinical psychopathic traits may be a learned response of some individuals to the business environment and not simply a group of characteristics that dominates their personality in every context. This may be another explanation of the finding in Babiak, Neumann and Hare’s [22] study. Although the overall association of psychopathy and leadership was not statistically significant in this study, findings indicated that presidents, vice presidents and CEOs were significantly more psychopathic than the middle and senior managers. Apart from that, due to the fact that the studies of Babiak [46] and Boddy [44] had a case study design, the generalizability of their results was limited as it was not possible for the author to draw general conclusions from just a small number of cases. However, a case study in this area of interest offers the possibility to explore in more depth the psychopathic personality of an individual as well as to gain a better understanding of the way in which these individuals function within an organization. For example, the case of Dave in Babiak’s [46] study has shown how a psychopathic individual interacts with his colleagues and bosses at the workplace for a sustained period of time. In addition, it provides further support to the dominant theoretical claim of the current research literature which suggests that primary psychopathy is directly related to a successful career movement into the highest Review organizational ranks [2]. Thus, these case studies provided further advancement on this particular field’s knowledge base and enhance reader’s understanding of the real-life phenomenon under investigation. A third limitation of the two case studies was associated with one of the methods used to assess participants’ psychopathic traits. Beyond the use of the reliable and valid clinical rating scale (PCL-SV) in Babiak’s [46] study, it was also implemented a method based on the observation, by co-workers [46], and respondents [47], of psychopathic behavior in others. Thus, the use of this method for data collection purposes might have introduced the potential of assessment bias. However, many studies have shown that psychopathic traits may be identified by ordinary, untrained individuals who work alongside and know well the participants under investigation [55,56]. A fourth limitation of all studies included in this review was the fact that they did not ask from independent evaluators to complete the clinical rating scales used to assess psychopathy, and thus the lack of a blind assessment method might have introduced the possibility of the assessor’s bias. Added to this, each case study included only one assessor. In Babiak, Neumann and Hare’s [22] study the main assessor was Paul Babiak who was working as an organizational psychologist in the HR Department of some companies. In Board and Fritzon’s study, the MMPI-PD was used which is a self-report tool designed to identify the presence of personality disorders. Although, the reliability of the collected data cannot be putted in question due to the fact that this specific tool has a very high internal consistency in a number of different settings and within different population samples [57], the authors decided to measure psychopathy indirectly with the use of 11 sub-scales that include certain behaviors closely related to psychopathy. They did not mention any other pure measurement of psychopathy that could have potentially found to be correlated with the MMPI-PD and therefore the reader is not completely aware of how many participants actually met the criteria of psychopathy as the empirical evidence for a possible overlap between psychopathic, histrionic and narcissistic personalities seem to be inconsistent [29]. Finally, this study had 12 drop outs (51 were initially recruited, but only 39 finally participated) from the corporate sample without providing any reason for that. 658 Review Georgios Kountouras Limitation of this Review The main limitation of this systematic review was the number of studies identified for inclusion. The author decided that only four studies met the inclusion criteria and thus the external validity of this review may be criticized. On the other hand, considering that the empirical evidence related to the topic of this review is very limited, the current dissertation was the first scientific attempt of summarizing, analyzing and critically evaluating all the available evidence on the psychopathy-leadership relationship. One solution to this problem for the author might be to broaden the inclusion criteria in order to identify more studies during the screening process. For this purpose, the author contacted a leading expert in the field of psychopathic leadership, Professor Clive Boddy, asking for his knowledge of other relevant studies, published or unpublished. Professor Boddy admitted that this topic is completely new and thus the number of studies is very limited. However, he suggested the author to expand his criteria and include also other personality types such as Narcissists and Machiavellians. The author decided not to include the so-called “Dark Triad” (Psychopaths, Narcissists, and Machiavellians) because after a thorough investigation in the current research literature, it was found that there are some inconsistencies regarding this construct. More specifically, it is not yet clear if these personalities differ with each other or if they only share some common traits indicating simply an overlap between them [58]. According to the recent research literature (e.g. [59-61]) Machiavellian personality include traits such as low empathy, flat affect, unethical decision making, a tendency to manipulate others, pathological lying and an egocentricity related to a focus exclusively on individualistic goals and not those of others. Narcissistic personality includes traits such as grandiosity, superiority, lacking trust and care for others, and superficial charm. These personalities including the psychopathic one include only sub-clinical traits and therefore they do not reflect the standardized diagnostic criteria of a personality disorder in any case. However, psychopathic personality is a wider term and thus it includes both narcissistic and Machiavellian traits [57]. Moreover, “Dark personality” is a constructed term that usually helps theorists to identify the group of traits that are more dominant in some individuals than in others [62]. As Psychopaths 659 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) can be presented with traits found to both Machiavellians and Narcissists and considering that the main aim of this study was not to investigate which group of traits are present at most in the business world, the author decided to include only the dimension of psychopathy which seems to have also a wider acceptance from the psychiatric community. Limitations of this Review’s Methods First of all, although the author searched only English-language journals, the possibility of finding other relevant studies in this area of interest is very limited. Therefore, the potential of language bias still exists, but it is very low. Secondly, publication bias was not able to be examined in this review because the use of a funnel plot is significant when the number of studies is at least 30 or above [49]. Thirdly, due to the fact that this project was for a Master’s purpose, only one individual, the author, was able to search for studies following a specific search strategy. In general, at least two reviewers should take part in the searching process in order to check and ensure that the inclusion criteria have been met. Strengths of this Review’s Methods In order to find relevant papers, published and unpublished in this area of interest the author contacted many leading experts including Dr Paul Babiak who has been working as an organizational psychologist in many large companies of the United States, Professor Robert Hare who is one of the most eminent researchers in the field of psychopathy, and Professor Clive Boddy who teaches now Leadership and Organization Behavior at Middlesex University Business School in London. Therefore, the possibility of missing any relevant paper in this particular area of interest or other international studies is very limited. In addition, the methodological quality of the included studies was assessed by two raters, the author and one research psychologist that hold an MBA Global. The kappa coefficient was calculated in order to test the inter-rater reliability (Appendix 2) and it was found that the level of agreement between the two raters for the QATQS regarding Babiak, Neumann and Hare’s [22] study was perfect, (κ=1, p<.005). Cohen’s κ was also run to determine if there was an agreement between the two raters’ judgment on the quality assessment of Board and Fritzon’s [28] study. Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? Although there was a good agreement, with κ = .74, the result was not statistically significant, (p>.005), meaning that the difference between the observed and expected agreement could also be zero. Therefore, this strong agreement might be occurred simply by chance. However, this non-significant result might be explained by the fact that QATQS overall methodological rating leads to only eight sections and thus an inter-rater agreement by chance is likely. Finally, a kappa statistic was also calculated to estimate the level of agreement between the two raters’ judgment on assessing the quality of the two case studies with the use of JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist. For the study of Babiak [46], a good agreement, (κ=.69, p<.005), on JBI quality assessment tool was found. A statistically significant Cohen’s κ of 0.71 indicating also a strong agreement was found for the JBI quality assessment tool with regards to Boddy’s [47] study. Last but not least, by designing a search strategy that included not only electronic searches, but also hand searching and searching of reference lists of included papers, the author is confident that all relevant studies were included in this systematic review. Thus, any conclusion arising from this review is based on synthesis of all available evidence in this area of interest which was one of the basic aims of this review. Generalizability of the Review’s Results The studies included in this review were limited in number and due to their diversity across their design, sample size, participants’ characteristics, and methods of assessing psychopathy; it is difficult to synthesize the evidence in order to draw generalized conclusions with strong confidence about the corporate world by using only a summary of data reported in these four studies. Theoretical and Practical Implications This review’s findings support the idea that personality disorders should be perceived as a continuum dimension of traits being distributed even in a completely functional and successful population sample rather than a categorical concept that defines only some mentally disordered individuals. Thus, an important theoretical implication of these findings is related to the psycho-social approach of personality disorders rather than to a “pure” psychiatric one that supports mainly the medical Review model of disease. However, it is important to be noted that the presence of these sub-clinical psychopathic traits in the corporate world should not be considered as “equal” with the presence of an antisocial personality disorder diagnosis. As it was found, corporate psychopaths display only in some degree some specific psychopathic behaviors (e.g. manipulation, pathological lying, superficial charm), without being identified with other features such as impulsivity, physical aggression, compulsiveness and criminality. In addition, not only corporate psychopaths do not meet all the diagnostic criteria for such a diagnosis, but also the expression of their psychopathic behavior is mainly restricted on the business setting [53]. Therefore, the quality, quantity and frequency of their “symptoms” are completely different compared to those observed in imprisoned population and mentally disordered individuals [28]. Another theoretical implication of this review’s findings is related to the concept of social constructivism and specifically to the way in which western culture constructs the idea of a “leader”. Some of the findings presented in this review suggested that despite their low productivity, poor management and leadership skills, and inability to inspire and motivate others, corporate psychopaths with leadership positions were seen as smart, ambitious, good strategic thinkers and good communicators. This conflicting idea about psychopathic leaders may reflect western societies’ expectation of possessing a specific group of traits that should characterize leaders. In this sense, a particular construct such as psychopathic leadership may be attributed with features (e.g. good strategic thinking and good communication skills) which in some way “counteract” the presence of the negative ones. In this way, corporate psychopaths may adopt a specific leadership role characterized mainly by manipulative skills, persuasiveness and pathological lying which are often perceived as charisma, and this role may be a form of the society’s self-fulfilling prophecy about how leaders should be in general [53]. Added to this, all studies included in this review had as samples only male participants and thus the association between how gender is constructed by western culture in relation to the psychopathic traits being present in high-ranking executives has also an important theoretical implication for qualitative research. Specifically, in many qualitative studies (e.g.[63]) it was shown that the main elements of the male identity are 660 Review Georgios Kountouras strength, ambition, and command, which are usually perceived with a positive meaning by the male population. Although dominance and aggression have found to be of less importance with regards to masculinity, they are often described by males as “desirable” traits because they reflect a sense of power and control rather than weakness [63]. Considering this evidence, it can be argued that psychopathic leadership may be a socially constructed dimension that reflects the “true male” that should be bold, ambitious, dominant and competitive, without radical emotional changes that could affect his mood. Thus, a suitable profession for this “true male” may be found within the corporate world. In this way, the sub-clinical psychopathic behavior of some individuals with leadership positions may be only a socially acceptable way of being professionally successful as “true males” in western and individualistically oriented corporations. Apart from that, many economists and financial experts have tried to identify the causes of the global financial crisis started few years ago. The findings of this review may have a limited power, but they may be an integral part of the full answer that these experts are trying to find. Due to the fact that corporate psychopaths manage to rise quickly at the highest positions of an organization and considering that their willingness for power, money and prestige is above company’s interests, an organization that has psychopathic individuals in leadership positions is likely to suffer a collapse from within [53]. An organizational toxic environment being mainly controlled by psychopathic high-ranking executives who’s their personal greed and egocentric personality often leads to corporate frauds and unethical business practices may be the reason of how many big companies finally collapsed despite their long lasting history and reputation [53]. However, the theory which supports that there is an association between the global financial crisis and psychopathic leadership is far more complicated than this simple description provided above as it takes into considering some other factors too (e.g. political decisions, government plans, unorthodox operation of financial organizations and misbehavior of the stock market). Thus, a further discussion would be a whole paper of its own. Finally, the most important practical implication of this review’s findings has to do with professionals such as organizational psychologists working in the Human Resources Department of 661 Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) most companies. These professionals should have a greater role within the company they work for by screening all the potential leadership candidates for psychopathy in order to contribute actively on the development of a better organizational environment. In conclusion, this review’s findings create awareness among organizational managers and mental health professionals that psychopathic high-ranking individuals exist in the business world and thus an extra caution should be taken during the selection of potential employees. Suggestions for Future Research First of all, further research in this area of interest would have great benefits from the use of an instrument specifically designed to measure psychopathy in business settings. Although the traditional reliable and valid measures of psychopathy such as the PCL-R and PCL-SV are able to identify the full range of psychopathic behaviors, they are not business-friendly and thus many companies do not include them in the overall assessment of their personnel. Therefore, an instrument that would be easy on its administration and written in a simple, non-clinical business-friendly language would be necessary for future studies conducted on this field [64]. In addition, it should not include items with stigmatizing effect for the business world, have good face validity, and most importantly it should be capable of collecting data not only for measuring psychopathy, but also for evaluating the specific leadership style associated with it. Secondly, future studies on psychopathic leadership should have ideally a longitudinal methodological design in order to investigate if specific psychopathic traits are responsible for leadership development. A longitudinal design eliminates the possibility of reverse causality and it is suitable for establishing a causal relationship between two factors. However, it would be difficult for future researchers to recruit a large number of participants before their adulthood in order to observe through multiple assessments of their personality how some specific traits that remain stable over a long period of time may be also responsible for the selection of a particular career pathway that involves leadership roles. For this future research project, an interdisciplinary team consisted of developmental and work psychologists, personality experts, independent statisticians, educators, and career advisors would be necessary in order to overcome successfully the above-mentioned difficulties. Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? Thirdly, future researchers should focus not only on the “dark” impact of psychopathic leadership on organizations, but also on the “bright” side of it. An unbiased and objective look into the aspects of psychopathic leadership would help them understand how psychopathic highranking executives think, make decisions, act and run an organization. Assessments of their cognitive functioning and EQ skills would be beneficial for comparisons purposes with other high-ranking executives without psychopathic traits. By gaining a further insight into the “nature” of psychopathic leaders, future researchers would be able to detect them more easily and prevent any destructive consequence of their leadership style. Added to this, future neuro-imaging studies will be able to provide further evidence regarding the neurobiology of psychopathy. By studying the brains of a fully functional and “successful” group of individuals identified with psychopathic traits and comparing them with those of imprisoned and mentally disordered populations, researchers will be able to observe not only the neuro-physiological differences and/or similarities between them, but also to conclude if there are distinct sub-types of psychopathy being responsible for a particular pattern of behavior. In addition, comparisons with a control group consisted of “healthy” individuals would be necessary in this type of research in order to be investigated if there is any abnormality in specific brain regions (e.g. limbic system, prefrontal cortex) that are activated during cognitive and emotional processes. These inter-group comparisons would also help scientists understand if psychopathic leadership is a socially constructed term that reflects a culturally-based idea of how leaders should be or if it has neurobiological origins too. Lastly, future studies that will investigate some other sub-clinical traits of different personality disorders including the narcissist and the obsessive-compulsive one would be certainly References 1. Cooke DJ, Michie C. Psychopathy across cultures: North America and Scotland compared. J. Abnorm. Psychol 108(1), 58–68 (1999). 2. Babiak P, Hare RD. Snakes in suits: When psychopaths go to work. App. Psychol 44(1), 171–188 (2006). 3. Hall J, Benning S. The “successful” psychopath: adaptive and subclinical manifestations of psychopathy in the general population. , Review beneficial in order to help researchers determine all the aspects of PDs that are associated at most with leadership in business settings. In addition, other future studies may contribute on the design of specific psycho-social programs focused on the enhancement of skills that are necessary in order to become one a good and efficient leader. However, the legal and ethical considerations should be firstly taken into account before telling if these leader development programs could be beneficial or not for the corporate world and society in general. Final Conclusions All things considered, although these review’s findings cannot be generalized to the corporate world due to the limited number of the included studies, there is an indication that the highly psychopathic corporate individuals often hold leadership positions within an organization. Future studies in this area of interest will help researchers establish a causal or simply a correlational relationship between psychopathy and leadership in business settings. The current systematic review was the first of its kind and thus it was also the first attempt of summarizing, presenting and critically evaluating all the empirical evidence associated with the psychopathic leadership literature. Future studies of different methodological designs will be necessary not only for providing further support to this review’s findings, but also for offering a solid ground to those researchers who want to conduct other systematic reviews around this topic. To put in a nutshell, research on this particular topic begins now to emerge and its implications on various scientific fields including Organizational Psychology, Behavioral Economics, and Business Administration seem to concern not only the experts on these fields, but also those psychiatrists who tend to adopt a more psycho-socially oriented approach of personality disorders. in Patrick C. (Ed.), Handbook of Psychopathy, Guilford, New York, NY, 459–478 (2006). 4. Lykken DT. Psychopathic personality: the scope of the problem, in Patrick C. (Ed.), Handbook of Psychopathy, Guilford, New York, NY, 3-13 (2006). 5. Patrick CJ. Back to the Future: Cleckley as a Guide to the Next Generation of Psychopathy Research. In Patrick C. (Ed.), Handbook of Psychopathy, Guilford, New York, NY, 605–617 (2006). 6. Hare RD. Predators: the disturbing world of the psychopaths among us. Psychol. Today 27(1), 54-6 (1994). 7. Edens JF, Marcus DK, Lilienfeld SO, et al. Psychopathic, not psychopath: taxometric evidence for the dimensional structure of psychopathy. J. Abnorm. Psychol 115(1), 131–144 (2006). 8. Guay JP, Ruscio J, Knight RA, et al. Ovid: A Taxometric Analysis of the Latent Structure of Psychopathy: Evidence for Dimensionality. J. 662 Review Georgios Kountouras Abnorm. Psychol 116(4), 701–716 (2007). paths: rarely challenged, often promoted. Why? Soc. Business. Rev 2(3), 254-269 (2007). 9. Murrie DC, Marcus DK, Douglas KS, et al. Youth with psychopathy features are not a discrete class: a taxometric analysis. J. Child. Psychol. Psych 48(7), 714-723 (2007). 26. Boddy CR. The dark side of management decisions: organizational psychopaths. Managt. Dec 44(10), 1461–1475 (2006). 10. Weiler BL, Widom CS. Psychopathy and violent behaviour in abused and neglected young adults. Crim.Behav. Ment. Health 6(3), 253–271 (1996). 27. Furnham A, Daoud Y, Swami V. “How to spot a psychopath’’ Lay theories of psychopathy. Soc. Psychiatry. Psychiatr. Epidemiol 44(6), 464–472 (2009). 11. Farrington DP. The importance of child and adolescent psychopathy. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol 7(3), 345-353 (2005). 28. Board BJ, Fritzon K. Disordered Personalities at Work. J. Psychol. Crime. Law 11(1), 17-32 (2005). 12. Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, et al. Linking antisocial behavior, substance use, and personality: An integrative quantitative model of the adult externalizing spectrum. J. Abnorm. Psychol 116(4), 645–666 (2007). 29. Torgersen S, Czajkowski N, Jacobson K, et al. Dimensional representations of DSM-IV cluster B personality disorders in a population-based sample of Norwegian twins: A multivariate study. Psychol. Med 38(11), 1617–1625 (2008). 13. Cangemi, Joseph P, Pfohl W. Sociopaths in high places. Organiz. Develop. J 27(1), 85–96 (2009). 14. Finkelstein S, Hambrick DC. Strategic Leadership: Top Executives and Their Effects on Organizations. West Publishing Company (1996). 15. Chatterjee A, Hambrick D. It’s all about me. Admin. Sci. Quarterly 52(1), 351–386 (2007). 16. Chemers M. Leadership effectiveness: An integrative review. Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Group Processes, 376–399 (2001). 17. Clark LA. Assessment and diagnosis of personality disorder: Perennial issues and an emerging reconceptualization. Ann. Rev. Psychol 58(1), 227–257 (2007). 18. Mathieu C, Neumann CS, Hare RD, et al. Corporate Psychopathy and the Full-Range Leadership Model. Assessment 59(8) (2014). 19. Gudmundsson A. Leadership and the rise of the corporate psychopath : What can business schools do about the “snakes inside”? J. Business. Ethic 2(2), 18–27 (2011). 20. Shaw JB, Erickson A, Harvey M. A method for measuring destructive leadership and identifying types of destructive leaders in organizations. Leadership Quart 22(4), 575–590 (2011). 21. Kets De Vries MFR. The Thought Leader Interview: Manfred F.R. Kets de Vries. Strategy + Business, 1–8 (2010). 22. Babiak P, Neumann CS, Hare RD. Corporate Psychopathy : Talking the Walk. Behav. Sci. Law 28(2), 174-193 (2010). 23. Deutschman A. Is your boss a psychopath? Fast. Company 96(1), 44-48 (2005). 24. Ouimet G. Dynamics of narcissistic leadership in organizations: towards an integrated research model. J. Manag. Psychol 25(7), 713-726 (2010). 25. Pech RJ, Slade BW. Organizational socio- 663 30. Clow KA, Scott HS. Psychopathic traits in nursing and criminal justice majors: A pilot study. Psychol. Rep 100(2), 495–498 (2007). 31. Coynes SM, Thomas TJ. Psychopathy, aggression, and cheating behavior: A test of the cheater-hawk hypothesis. Person. Individ. Diff 44(2008), 1105–1115 (2008). 32. Sellbom M, Verona E. Neuropsychological correlates of psychopathic traits in a non-incarcerated Sample. J. Res. Person 41(2), 276-94 (2007). 33. Sadeh N, Verona E. Psychopathic personality traits associated with abnormal selective attention and impaired cognitive control. Neuropsychology 22(5), 669-680 (2008). 34. Corr PJ. The psychoticism–psychopathy continuum: A neuropsychological model of core deficits. Person. Individ. Diff 48(6), 695-703 (2010). 35. Boddy CR, Ladyshewsky RK, Galvin P. The Influence of Corporate Psychopaths on Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Commitment to Employees. J. Business. Ethic 97(1), 1–19 (2010). 36. Hogan R. Trouble at the top: Causes and consequences of managerial incompetence. Consult. Psychol. J 46(1), 9–15 (1994). 37. Hogan R, Hogan J. Assessing leadership: A view from the dark side. Int. J. Select. Assess 9(1), 40–51 (2001). 38. Judge TA, Piccolo R, Kosalka T. The bright side and dark side of leader traits: A review and theoretical extension of the leader trait paradigm. Leadership. Quarter 20(6), 855–875 (2009). 39. Hiller N, DeChurch L, Murase T, et al. Searching for outcomes of leadership: A 25-year review. J. Managt 37(4), 1137–1177 (2011). 40. Antonakis J, Day DV, Schyns B. Leadership and individual differences: At the cusp of a renaissance. The Leadership. Quarterly 23(4), 643-650 (2012). Neuropsychiatry (London) (2017) 7(5) 41. Zaccaro S. Individual differences and leadership: Contributions to a third tipping point. Leadership. Quart 23(2012), 718–728 (2012). 42. Padilla A, Hogan R, Kaiser RB. The toxic triangle: Destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. Leadership. Quart 18(3), 176–194 (2007). 43. Khoo HS, Burch GSJ. The “dark side” of leadership personality and transformational leadership: An exploratory study. Person. Individ. Diff 44(1), 86–97 (2008). 44. Boddy CR. The Implications of Corporate Psychopaths for Business and Society : An Initial Examination and A Call To Arms. Aus. J. Business. Behav. Sci 1(2), 30–40 (2005). 45. Lilienfeld S, Latzman RD, Watts AL, et al. Correlates of psychopathic personality traits in everyday life: Results from a large community survey. Front. Psychol 5(7), 1–11 (2014). 46. Babiak P. When psychopaths go to work: a case study of an industrial psychopath. App. Psychol 44(2), 171-188 (1995). 47. Boddy CR. Psychopathic Leadership A Case Study of a Corporate Psychopath CEO. J. Business. Ethic 11(6), 01-16 (2015). 48. Thomas J, Harden A, Oakley A, et al. Integrating qualitative research with trials in systematic reviews: An example from public health. BMJ 328(1), 1010-1012 (2004). 49. Boland A, Cherry M, Dickson R. Doing a systematic review: A Student’s Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications (2014). 50. The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (2008). 51. Hare RD. Manual for the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R). Toronto, CA: Multihealth Systems (1991/2003). 52. Coolican H. Research methods and statistics in psychology (5th edition). London: Hodder (2004). 53. Boddy CR. The Corporate Psychopaths Theory of the Global Financial Crisis. J. Business. Ethic 102(2), 255–259 (2011). 54. Kassin S. Psychology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc (2013). 55. Lilienfeld SO, Andrews BP. Development and preliminary validation of a self-report measure of psychopathic personality traits in noncriminal populations. J. Person. Assess 66(3), 488-524 (1996). 56. Mahaffey KJ, Marcus DK. Interpersonal perception of psychopathy: A social relations analysis. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol 25(1), 53-74 (2006). 57. Hare RD, Neumann CN. The PCL-R Assessment of psychopathy: development, struc- Is there any Association between Psychopathy and Leadership in Business Settings? tural properties, and new directions, in Patrick C. (Ed.), Handbook of Psychopathy, Guilford, New York, NY, 58-88 (2006). pathic personality: Bridging the gap between scientific evidence and public policy. Psychol. Sci. Public. Interest 12(3), 95–162 (2011). 58. Paulhus DL, Williams KM. The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Person 36(6), 556–563 (2002). 61. Wu J, LeBreton JM. Reconsidering the dispositional basis of counterproductive work behavior: The role of aberrant personality traits. Person. Psychol 64(3), 593–626 (2011). 59. Christie R, Geis FL. Studies in Machiavellianism. New York, NY: Academic Press (1970). 62. Lynam DR, Widiger TA. Using a general model of personality to identify the basic elements of psychopathy. J. Person. Disord 21(2), 160–178 (2007). 60. Skeem J, Polaschek D, Patrick C, et al. Psycho- Review 63. Edley N. Analysing Masculinity: Interpretative Repertoires, Ideological Dilemmas and Subject Positions.” 189 - 228 in Discourse as Data: A guide for analysis edited by Margaret Wetherell, Stephanie Taylor and Simeon J. Yates. London: Sage (2001). 64. Mathieu C, Babiak P. Validating the B-Scan Self: A self-report measure of psychopathy in the workplace. Int. J. Select. Assess 24(3), 272–284 (2016). 664