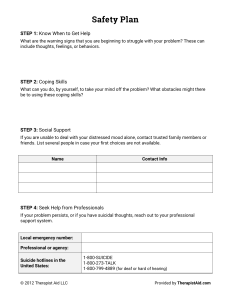

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management Why is employees’ emotional intelligence important?: The effects of EI on stresscoping styles and job satisfaction in the hospitality industry Hyo Sun Jung, Hye Hyun Yoon, Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) Article information: To cite this document: Hyo Sun Jung, Hye Hyun Yoon, (2016) "Why is employees’ emotional intelligence important?: The effects of EI on stress-coping styles and job satisfaction in the hospitality industry", International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 28 Issue: 8, pp.1649-1675, https:// doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2014-0509 Permanent link to this document: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2014-0509 Downloaded on: 20 May 2019, At: 03:45 (PT) References: this document contains references to 118 other documents. To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 3598 times since 2016* Users who downloaded this article also downloaded: (2012),"Emotional intelligence and emotional labor acting strategies among frontline hotel employees", International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 24 Iss 7 pp. 1029-1046 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111211258900">https:// doi.org/10.1108/09596111211258900</a> (2004),"How emotional intelligence can improve management performance", International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 16 Iss 4 pp. 220-230 <a href="https:// doi.org/10.1108/09596110410537379">https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110410537379</a> Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by emeraldsrm:108246 [] For Authors If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation. *Related content and download information correct at time of download. The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/0959-6119.htm Why is employees’ emotional intelligence important? The effects of EI on stress-coping styles and job satisfaction in the hospitality industry Emotional intelligence 1649 Hyo Sun Jung and Hye Hyun Yoon Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) Department of Culinary Arts and Food Service Management, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea Received 9 October 2014 Revised 22 February 2015 30 April 2015 15 June 2015 Accepted 29 September 2015 Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this study is to examine the effects of hospitality employees’ emotional intelligence (EI) on their stress-coping styles and job satisfaction. Design/methodology/approach – The sample consisted of 366 food and beverage employees in the Korean hospitality industry. The validity and reliability of the respondents’ replies regarding EI, stress-coping styles and job satisfaction were tested through exploratory factor analysis, reliability analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. Once the measure was validated, a structural equation model was used to test the validity of the proposed model and hypotheses. Findings – The results showed that the elements of EI (i.e. self-emotion appraisal [SEA], use of emotion [UOE], regulation of emotion [ROE] and others’ emotion appraisal [OEA]) had a significant, positive effect on the cognitive-appraisal coping style, whereas only SEA and UOE had a significant, positive effect on the problem-solving coping style. Meanwhile, SEA had a significant, negative effect on the emotion-focused coping style. In addition, employees’ problem-solving and cognitive-appraisal stress-coping styles showed a significant, positive effect on their job satisfaction. Employees’ UOE and ROE demonstrated a significant, positive effect on job satisfaction. Research limitations/implications – The generalizability and, therefore, implications are limited to the Korean hotels and family restaurants. Future research needs to closely examine models and variables which may become the causes of individual traits, relationship traits and leadership. Originality/value – Strategies to cope with stress and job satisfaction used by family restaurant employees showed more sensitive effects of control than hotel employees did in the organic causal relationships between EI and strategies to cope with stress/job satisfaction. The results of this study, which indicate that hospitality companies can increase employees’ job satisfaction by enhancing their employees’ EI, suggest detailed and practical alternatives to human resource management, as employees with higher degrees of EI can bring positive outcomes to both organizations and employees. Hospitality employees’ EI is significant in terms of organizational performance. Keywords Hospitality industry, Emotional intelligence, Employees attitudes Paper type Research paper 1. Introduction Can employees with high emotional intelligence (EI) cope with a stressful situation reasonably well? Does the ability to respond to stress well affect employees’ job satisfaction? These questions are the driving themes of this paper, which examines EI and stress-coping styles to identify organic, causal relationships between them and job satisfaction. EI is the universal ability to perceive others’ emotions and indicate suitable self-emotions (Mayer et al., 2002). The competitiveness of a business is affected by the International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management Vol. 28 No. 8, 2016 pp. 1649-1675 © Emerald Group Publishing Limited 0959-6119 DOI 10.1108/IJCHM-10-2014-0509 IJCHM 28,8 Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) 1650 organizational passion, sense of responsibility and reliability of talented employees, as well as their intellectual properties. Organizations utilize passion and reliability as criteria for the selection of workers in addition to their ability to perform the cognitive aspect (Michaels et al., 2001). For this reason, businesses pay attention to creative and autonomous talented persons who can flexibly perform their duties. This means that the ability to smoothly perform duties together with colleagues and handle one’s own emotions has become important not only for individuals’ lives but also for success in organizations. Because even talented persons with excellent intellectual capabilities hinder a business’ long-term growth if they have little devotion and loyalty (Dickey et al., 2011), EI has become a criterion of employee desirability. Rational abilities are indicated by the intelligence quotient (IQ), and emotional abilities are indicated by EI. Regarding the relationship between IQ and EI, Goleman (1995) argued that success in relationships between superiors and subordinates, including general human relations, are not determined by cognitive intelligence (i.e. the head) but by EI (i.e. the heart), thereby advocating a logic that emotions are more important than intelligence when predicting individuals’ success or happiness. Furthermore, he advised that emotional abilities also have an important role in selecting employees who could contribute predicting outstanding business abilities. For these reasons, paying attention to employees’ EI has been known to help employees endure stress in fiercely competitive organizational environments, enhance loyalty to the firm, share positive energy with colleagues and team with colleagues to achieve goals (Hur et al., 2011). Palmer et al. (2002) indicated that the emotions of individual employees were important in maximizing individuals’ performances and that individual performances might vary according to their emotions. Caruso and Salovey (2004) argued that emotions were not only important but also necessary to achieve success in taking appropriate actions to solve problems and coping with changes. In particular, given that EI is not a gift but can be developed and improved through education and training (Salovey et al., 2002; Slaski and Cartwright, 2003), it is considered useful in in meaningful marketing strategies for business performance too. In particular, employees in the hospitality industry who should treat their customers with positive emotions such as bright smiles had higher intensity of emotional labor compared to ordinary occupational groups (Chu et al., 2012). Furthermore, EI is necessary to control individuals’ moods, which is a very important factor in the case of service-oriented businesses, where employees’ roles at counters are to communicate face-to-face with customers (Lee and Ok, 2012). Service organizations determine the norms for emotional expressions and require employees to observe these norms. These emotional expressions are determined and required by organizations and are important components of jobs that must be performed by employees currently (Shani et al., 2014). Such emotional labor can be determined by the degree of the employees’ EI (Johnson and Spector, 2007). For example, Psilopanagioti et al. (2012) said that if employees’ EI is excellent, it can help them carry out the positive performance of emotional labor, thereby increasing job satisfaction. Also, in the case of organizations that manage EI well, the employees have passion for their companies and display will, involvement, affection and liveliness (Day and Carroll, 2004; Weinberger, 2003; Wong and Law, 2002). In contrast, feelings of helplessness, stress and anxiety can be easily triggered among employees to affect the organization adversely (Aghdasi et al., 2011; Jung and Yoon, 2012; Sakloske et al., 2012). However, studies conducted thus far examined only the organic relations between EI, coping styles and satisfaction (Daus and Ashkanasy, Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) 2005; Kafetsios and Zampetakis, 2008; Kim and Agrusa, 2011; Moradi et al., 2011; Mousavi et al., 2012). EI can motivate individuals based on their abilities to perceive (self-emotion appraisal, SEA), control (regulation of emotion, ROE) and utilize (use of emotion, UOE) their emotions and those of others (others’ emotional appraisal, OEA), as well as enabling them to contribute to an organization’s performance through the formation of smooth human relations with all employees of the organization (Labo, 2005). Hence, this study divided EI into four elements of OEA, UOE, SEA and ROE (Mayer and Salovey, 1997) and attempted to investigate the sub-elements of EI that affect stress-coping styles and job satisfaction. We believe that the study can suggest practical implications to executives by providing them with the aspects of EI that help smart response to stressful situation and satisfaction enhancement. Therefore, this study focuses on individuals’ EI based on the study results where individuals’ decision-making or behavioral bases are based more on emotional than cognitive aspects (Salovey et al., 2002). It is assumed that as employees with high EI are quick to understand the requirements and values of stakeholders related to organizations, manage their stress or crises well and have good relations with others, they are emotionally comfortable and, thus, positively affect job satisfaction. The propose of this study is: • to investigate the effect of sub-factor in EI on stress-coping styles and satisfaction; and • to analyze the effect of employees’ stress-coping styles on job satisfaction (Figure 1). Emotional intelligence 1651 2. Literature review and conceptual model 2.1 Emotional intelligence in the hospitality industry Research on EI in the hospitality industry largely focused on positive performance. In particular, Goleman (1998) advised that the high EI of service employees has direct and positive effects on customers’ responses. In a study conducted on employees in the hospitality industry, Langhorn (2004) demonstrated that the EI of employees in the leisure and restaurant industries in the UK is closely related to company performance. Scott-Halsell et al. (2007) found that respondents’ EI and leadership skills were highly Figure 1. Research model of EI, stress-coping styles and job satisfaction IJCHM 28,8 Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) 1652 correlated with each other, and the level of EI among employees in the hospitality industry was above average compared to other industries so that employees’ performance can be estimated based on their EI level. Scott-Halsell et al. (2008) compared EI of managers and graduate students and reported that managers’ EI was significantly higher than that of graduate students and observed that EI was an essential element in the post of a leader in the hospitality industry. According to Cha et al. (2008), groups in which the EI of foodservice industry employees is high can also demonstrate excellent stress management abilities and social skills. Cichy et al. (2008) divided the results of the validation of measured variables of EI among private club managers into three factors: in (oneself), out (others) and relationships (interpersonal relationships). Kim and Agrusa (2011) examined the EI of hotel and restaurant service employees and found that it varied according to demographic and personal characteristics, which also significantly affected strategies used to cope with stress. According to Jung and Yoon (2012), the EI of hotel employees was closely related to counterproductive behavior (negative) and organizational citizenship behavior (positive). In addition, Lee and Ok (2012) identified significant causal relations among employees’ EI, labor exhaustion and job satisfaction. They determined that EI can reduce emotional depletion and unbalance in a work environment, which was followed by an increase in job satisfaction. Prentice and King (2013) verified the effects of casino employees’ EI on their adaptability and host performance. Meanwhile, Min (2012) demonstrated that a tour guide with high levels of EI also displayed high job performance. Wolfe and Kim (2013) reported that EI of hotel employees was an important variable to predict their job satisfaction, and the more excellent their EI in a hotel company, the higher their longevity. As such, many studies focused on the hospitality industry, including hotels, restaurants and hospitality-related companies, have discovered that EI can reduce stress, burnout and the separation rate while increasing satisfaction and performance. 2.2 Model development and hypotheses 2.2.1 Emotional intelligence, stress-coping styles and job satisfaction. EI, as defined by Mayer and Salovey (1997), refers to: […] the ability to perceive accurately, appraise, and express emotion; the ability to access and/or generate feelings when they facilitate thought; the ability to understand emotion and emotional knowledge; and the ability to regulate emotions to promote emotional and intellectual growth (p. 10). EI comprises four dimensions: OEA, UOE, SEA and ROE (Bande et al., 2015; Jung and Yoon, 2012; Lee and Ok, 2012; Mayer and Salovey, 1995; Wong and Law, 2002). In terms of sub-factors, OEA is the ability to recognize and comprehend the emotions of individuals; thus, the UEO refers to the ability to utilize individual emotional information for individual performance and constructive activities. SEA is the ability to perceive and indicate one’s emotions accurately; the ROE means the ability to demonstrate individual emotions through appropriate behavior depending on given situations (Wong and Law, 2002). Stress-coping, as defined by Lazarus (1998), refers to “person’s constantly changing cognitive and behavioral effects to meet specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person (p. 202)”. Folkman et al. (1986) noted that cognitive-appraisal and problem-solving coping styles and emotion-focused coping styles changing relationship between humans and the Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) environment in a stressful situation were important stress-coping strategies (Folkman and Lazarus, 1980; Oakland and Ostell, 1996). Aldwin and Revenson (1987) emphasized on the importance of three stress-coping styles noting that problem-solving and cognitive-appraisal coping styles played the role of a buffer in coping with stress, but emotional methods had adverse psychological effects. Based on Billings and Moos’s (1981), this study divides stress-coping styles into cognitive-appraisal coping, problem-solving coping and emotion-focused coping. The cognitive-appraisal coping style tries to handle one’s appraisal of the stressful situation (Meichenbaum, 1985). The problem-solving coping style is aimed at doing something to modify the cause of the stress to prevent or supervise it (Collins, 2008). Also, the emotion-focused coping style is aimed at decreasing or controlling the emotional distress associated with the situation (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). Job satisfaction is: […] an attitude that individuals have about their jobs. Job satisfaction results from their perception of their jobs and the degree to which there is a good fit between the individual and the organization (Ivancevich et al., 1997, p. 86) Locke (1969, p. 317). Locke (1969, p. 317) defined job satisfaction as the “pleasant emotional condition resulting from the evaluation of one’s job as achieving or facilitating one’s job standards”. Spagnoli et al. (2012) suggested that from a long-term perspective, job satisfaction positively affects attitudes toward the job. Therefore, it is a broad concept that includes consciousness about a set of factors in the workplace and the job itself (Gil et al., 2008). 2.2.2 Relationship between emotional intelligence and stress-coping styles. In a similar study that examined the relationship between EI and positive stress-coping styles, such as cognitive-appraisal coping and problem-solving coping, Gohm et al. (2005) explained that if employees’ EI improved, stress-coping styles related to organizational performance would be significantly increased, thereby exhibiting positive relationships between EI and employees’ stress-coping styles. In addition, Noorbakhsh et al. (2010) said that employees’ EI and problem-focused coping style had a positive relationship. Kim and Agrusa (2011) also indicated that the EI of employees in the hospitality industry was positively correlated with job-focused style to cope with stress. People high in EI are thought to be better prepared to cope with stressful situations (MacCann et al., 2011). Moradi et al. (2011) noted the correlation between EI and positive coping behaviors (e.g. cognitive-appraisal coping and problem-solving coping). Por et al. (2011) suggested that EI can help solve problems in stressful situations and plays an important role in increasing well-being. In a study that examined the correlations between the sub-elements of EI and styles to cope with stress, Rogers et al. (2006) found that emotional regulation was closely related with cognitive coping, whereas Sakloske et al. (2012) verified that EI (e.g. ROE) was significantly correlated with task-focused coping style with problem-solving. In addition to the aforementioned studies, other researchers have indicated that employees with high EI used cognitive coping or problem-solving styles in stressful situations (Austin et al., 2010; Downey et al., 2010; Houghton et al., 2012; Mikolajczak et al., 2008). Based on these previous findings, the present study assumed that employees’ EI was positively correlated with both cognitive-appraisal coping and problem-solving coping styles. Emotional intelligence 1653 IJCHM 28,8 H1. EI is positively related to cognitive-appraisal coping. H1a. Others’ emotion appraisal (OEA) is positively related to cognitive-appraisal coping. H1b. Self-emotion appraisal (SEA) is positively related to cognitive-appraisal coping. 1654 H1c. Use of emotion (UOE) is positively related to cognitive-appraisal coping. H1d. Regulation of emotion (ROE) is positively related to cognitive-appraisal coping. Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) H2. EI is positively related to problem-solving coping. H2a. Others’ emotion appraisal (OEA) is positively related to problem-solving coping. H2b. Self-emotion appraisal (SEA) is positively related to problem-solving coping. H2c. Use of emotion (UOE) is positively related to problem-solving coping. H2d. Regulation of emotion (ROE) is positively related to problem-solving coping. In a study of the relationship between employees’ EI and negative stress-coping styles to emotion, Salovey et al. (2000) indicated that emotion regulation derived from EI was closely related with emotional coping style. Ciarrochi et al. (2002) mentioned that weak ability to control personal emotion results in negative response to stress because of recognition of emotions such as hassles, suicidal thoughts and depression in a stressful situation. Pau and Croucher (2003) also pointed out that people with low EI tend to react emotionally to minor stresses by sensitively responding to them. Hunt and Evans (2004) suggested that low EI is associated with anxiety stress-coping style. Rogers et al. (2006), and Shah and Thingujam (2008) observed that when one lacked in emotion controlling capabilities among EI, one coped with stress in an emotional style. Sakloske et al. (2007) reported that EI and emotion-focused stress-coping styles had a negative relationship, meaning that the higher EI, the lower possibility one had of emotion-focused copings styles in a stressful situation. Noorbakhsh et al. (2010) argued that people with low EI in an aspect of using and controlling individual’s emotion are more likely to emotionally respond to stress. In addition, Vergara et al. (2010) identified a negative relationship between EI and passive coping styles, such as cognitive avoidance and emotional discharge. Kim and Agrusa (2011) argued that low EI means responding to stress in a more emotion coping style, pointing out the negative correlation between EI and neuroticism. Moradi et al. (2011) mentioned that EI significantly affects the coping style of emotional and somatic inhibition and argued that lower EI is linked to negative response to stress because of weak emotion-controlling ability. Wons and Barqiel-Matusiewicz (2011) also argued that people with low EI tend to respond depending on their emotions, trying only to avoid stressful situation. Davis and Humphrey (2012) said that people with excellent EI deal with stress with minimal evasive measure. Based on these previous findings, the present study assumed that employees’ EI was negatively correlated with emotion-focused coping style (Gooty et al., 2014). H3. EI is negatively related to emotion-focused coping. H3a. Others’ emotion appraisal (OEA) is negatively related to emotion-focused coping. Emotional intelligence H3b. Self-emotion appraisal (SEA) is negatively related to emotion-focused coping. H3c. Use of emotion (UOE) is negatively related to emotion-focused coping. Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) H3d. Regulation of emotion (ROE) is negatively related to emotion-focused coping. 2.2.3 Relationship between stress-coping styles and job satisfaction. In a work situation, the stress-coping styles that employees use produces different degrees of job satisfaction. For example, cognitive-appraisal and problem-solving coping styles increase job satisfaction, whereas emotion-focused coping style decreases job satisfaction. Several studies identify the two different viewpoints. First, regarding the study on the relationship between stress-coping styles of positive aspect and job satisfaction, Welbourne et al. (2007) said that problem-solving coping and cognitive coping styles were positively related with job satisfaction. Also, Park and Adler (2003) advised that as problem-solving coping and cognitive-appraisal coping styles were positively correlated with physical health and well-being, they also positively affected job satisfaction. Littrell and Beck (2001) indicated that problem-solving-focused cognitive style is a driving force that leads employees to adapt to stressful situations faster and solve problems faster than emotional style. In terms of another type of positive stress-coping style, Golbasi et al. (2008) observed that although optimistic coping style (such as problem-focused coping; Strutton and Lumpkin, 1992) in stressful situations are positively correlated with job satisfaction, they further emphasized the fact that different levels of job satisfaction depend on the styles used to cope with stress (Reissner et al., 2008). Chen et al. (2009) noted that constructive stress-coping (e.g. talk to spouse and relative and friends about problem) is positively correlated with job satisfaction, according to Kim (2010). In the case of organizations with appropriate strategies for coping with stress, turnover intent resulting from job stress decreases as job satisfaction increases. Studies of the relationship between stress-coping styles of negative aspects and job satisfaction, such as Callan et al. (1994), have indicated that using emotion-focused style to cope with stress might cause negative behavior in employees be anxiety and depression, which can result in job dissatisfaction. According to Brown (1996), employees who use avoid-coping styles in stressful situations tend toward dissatisfied with jobs. Littrell and Beck (2001) said that emotional styles also reduce negative behavior in organizations and enhance job satisfaction. Golbasi et al. (2008) noted that lethargic-coping style (such as avoid coping) is negatively correlated with job satisfaction; Chen et al. (2009) found that destructive stress-coping (e.g. stay away from everyone and increased smoking and drinking) is negatively correlated with job satisfaction. In addition, as avoid-coping styles can bring about negative performance caused by maladjustment to organizations and environments, they would also negatively affect job satisfaction (Armstrong-Stassen, 2004; Carver et al., 1993). Song (2008) suggested that as emotion-focused coping style is positively related with job exhaustion and problem-focused coping style is negatively related with employees’ exhaustion, styles for coping with stress are significantly related with job satisfaction. As such, most previous studies have verified that job satisfaction varies according to 1655 IJCHM 28,8 1656 individuals’ coping styles in stressful situations (Amber Raza and Ali, 2007; BhuIiar et al., 2012; Shimizu and Nagata, 2003). Based on these previous results, the present study assumes that cognitive-appraisal coping and problem-solving coping styles positively affect job satisfaction, whereas emotion coping style negatively affects job satisfaction. H4. Stress-coping styles are positively (or negatively) related to job satisfaction. H4a. Cognitive-appraisal coping is positively related to job satisfaction. H4b. Problem-solving coping is positively related to job satisfaction. Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) H4c. Emotion-focused coping is negatively related to job satisfaction 2.2.4 Relationship between emotional intelligence and job satisfaction. According to Wong and Law (2002), senior and junior coworkers’ EI did not affect job performance, although both had a positive effect on job satisfaction. It was mentioned that ROE shows the highest correlation with job satisfaction. Also, Brackett et al. (2010) said that emotion regulation ability had a positive effect on employees’ satisfaction, because employees with high EI who can control their emotions can also favorably accept positive emotion and support from the organization, resulting in high job satisfaction. Guleryuz et al. (2008) suggested that employees’ job satisfaction was observed to be associated with ROE and UOE. A research that considered EI and job satisfaction from the macroscopic perspective is as follows. Mayer and Salovey (1995) indicated that employees with excellent abilities to efficiently control and utilize their emotions used to be more satisfied. Also, Daus and Ashkanasy (2005) noted that EI is an important factor in job satisfaction. Fariselli et al. (2008) found that employees with high EI experienced low stress in job situations, which can be used as a variable to estimate performance, including employees’ job satisfaction; its estimation accuracy was around 60 per cent. Kafetsios and Zampetakis (2008) claimed that not only did employees’ EI have a direct relationship with job satisfaction but also indirect effect was present between EI and job satisfaction, with both positive and negative effects. Lee and Ok (2012) proposed that employees with high EI were more sympathy, suggesting that it is indirectly related to job satisfaction through the mediating roles of personal accomplishment. Overall, the prior studies suggested that employees’ EI is an important leading variable for enhancing job satisfaction (Çekmecelioğlu et al., 2012; Law et al., 2008; Lope et al., 2006; Sy et al., 2006; Wolfe and Kim, 2013). H5. EI is positively related to job satisfaction. H5a. Others’ emotion appraisal (OEA) is positively related to job satisfaction. H5b. Self-emotion appraisal (SEA) is positively related to job satisfaction. H5c. Use of emotion (UOE) is positively related to job satisfaction. H5d. Regulation of emotion (ROE) is positively related to job satisfaction. 3. Research methodology 3.1 Data collection and procedure The data utilized for this study were collected in 2012 from food and beverage employees in two hospitality sectors in South Korea. For this study, it selected deluxe hotel and family restaurant in the same number as a company of representing Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) hospitality industries. The following are the process of each sampling. A convenience sample was chosen from the participants, which comprised all employees of the five target hotels (250 samples) and five family restaurants (250 samples). After removing incomplete questionnaires, we obtained 336 valid samples for data analysis (response rate of 73.2 per cent): • Deluxe hotel: The participants in this study were employees working in the food and beverage division of five five-star hotels. Among 12 five-star chain-hotels located in Seoul, 10 hotels whose human resource management (HRM) department provided organic collaboration were selected. Employees of having responded to self-administered questionnaires were presented the fixed gift card. • Family restaurant: Five-ranked family restaurants were selected according to their sales in 2011. Questionnaire survey was conducted targeting employees of working at each of the family restaurants by receiving permission of five franchise head offices. Two branches per one brand were randomly extracted. The corresponding branches were supported the prescribed get-together expenses. 3.2 Instrument development To measure employees’ EI, this study applied the work of Mayer and Salovey (1997) and Wong and Law (2002). The study examined four dimensions of employees’ EI (Cartwright and Pappas, 2008; Cote and Miners, 2006; Mayer and Salovey, 1997; Wong and Law, 2002): OEA, UOE, SEA and ROE (Appendix 1). EI was measured by 16 items based on a seven-point Likert-type scale (here after). Stress-coping styles were measured using 12 items by Billings and Moos (1981, 1984) and Moradi et al. (2011). The study explores three dimensions of employees’ stress-coping styles (Billings and Moos, 1981): cognitive-appraisal coping, problem-solving coping and emotion-focused coping. Also, Job satisfaction was measured using five items by Cammann et al. (1983), Spector (1985) and Ko (2012). The questionnaire also included questions obtaining characteristics of respondents (e.g. gender, age and education level) and job-related information (e.g. tenure and company statues). 4. Results 4.1 Descriptive statistics of sample The characteristics of the sample are presented in Table I. The majority of the employees (55.4 per cent) were male. The participants’ mean age was 33.27 (⫾7.95) years; 44.5 per cent were 30-39 years of age. Most participants (41.8 per cent) had a university degree. All respondents had been working for five years or less in current company (53.8 per cent), and their company types were deluxe hotel (55.7 per cent) and family restaurant (44.3 per cent). 4.2 Measurement model Following the two-step approach (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988), a confirmatory factor analysis was practiced to estimate the fit of the eight-factor model using analysis of moment structure (AMOS) programs. As shown in Table II, all t-values exceeded 8.0 (p ⬍ 0.001), and each indicator standardized loadings exceeded 0.60 (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). The Cronbach’s alpha (0.839-0.932) and composite construct reliability estimates (0.701-0.896) of each measurement scale exceeded 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978). In Emotional intelligence 1657 IJCHM 28,8 Characteristic Gender Male Female Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) 1658 Age 21-29 years 30-39 years Older than 40 years Educational level College university University Graduate university Tenure 5 years or fewer Table I. Profile of the samples 6-9 years N (%) 10 years or more Hotel (N ⫽ 204) Family restaurant (N ⫽ 162) Total (N ⫽ 366) 115 (56.3) 89 (43.7) 75 (46.2) 87 (53.8) 203 (55.4) 163 (44.6) 44 (21.6) 95 (46.6) 65 (31.8) 80 (49.3) 68 (41.9) 14 (8.8) 124 (33.8) 163 (44.5) 79 (21.5) 57 (27.9) 87 (42.6) 74 (45.6) 66 (40.7) 131 (35.7) 153 (41.8) 60 (29.5) 22 (13.7) 82 (22.5) 93 (45.5) 62 (30.3) 49 (24.0) 104 (64.1) 33 (20.3) 25 (15.6) 197 (53.8) 95 (25.9) 74 (20.2) addition, the average variance extracted of all factors (OEA ⫽ 0.725; SEA ⫽ 0.691; UOE ⫽ 0.672; ROE ⫽ 0.693; cognitive-appraisal coping ⫽ 0.745; problem-solving coping ⫽ 0.632; emotion-focused coping ⫽ 0.576; and job satisfaction ⫽ 0.713) exceeded 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Also, discriminant validity was evident because the variance extracted estimates, ranging from 0.61 to 0.75, exceeded all squared correlations for each constructs, ranging from 0.01 to 0.34. The results of confirmatory measurement models proposed the fit of measurement model [2 ⫽ 954.767; df ⫽ 467; p ⬍ 0.001; 2/df ⫽ 2.044; goodness-of-fit index (GFI) ⫽ 0.864; normed fit index (NFI) ⫽ 0.899; comparative fit index (CFI) ⫽ 0.945; root square error of approximation (RMSEA) ⫽ 0.053; and root mean square residual (RMR) ⫽ 0.068]. To examine a common method bias (CMB), we tested for common method variance using Harman’s single-factor test (Harman, 1967; Podsakoff et al., 2003). An exploratory factor analysis showed eight factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.00 (Appendix 2). The scale items exhibited eight factors (33 variables) that explained 77.028 per cent, with the first factor (job satisfaction) explaining 38.023 per cent and the last factor (emotion-focused coping) explaining 3.354 per cent of the total variance. Additionally, CMB error was verified through marker variable, which was used in researches by Lindell and Whitney (2001) and Hon and Lu (2010). As Table III, the correlation between exogenous variable (EI) and endogenous variable (coping style and job satisfaction) had no significant difference (partial correlation) from when having used job engagement as marker variable.. Accordingly, the probability that CMB error will occur in this study was indicated to be very small. The correlations, means and standard deviations are shown in Table III. The correlation analysis result showed that emotion-focused coping and all other variables had a negative correlation, showing that the hypothesis and direction were consistent. In addition, it was studied that other variables of general characteristics showed a low correlation with the independent and dependent variables (⬍0.20), indicating that Construct (Cronbach’s alpha) Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) Others’ emotion appraisal (0.922) OEA1 OEA2 OEA3 OEA4 Standardized loadings t-value 0.871 0.869 0.877 0.787 Fixed 22.057 22.414 18.615 Self-emotion appraisal (0.899) SEA1 SEA2 SEA3 SEA4 0.812 0.865 0.866 0.780 Fixed 19.157 19.188 16.649 Use of emotion (0.891) UOE1 UOE2 UOE3 UOE4 0.841 0.819 0.781 0.838 Fixed 18.333 17.114 18.925 Regulation of emotion (0.900) ROE1 ROE2 ROE3 ROE4 0.870 0.892 0.757 0.805 Fixed 22.320 17.238 19.017 Cognitive-appraisal coping (0.922) CAC1 CAC2 CAC3 CAC4 0.809 0.845 0.899 0.898 Fixed 18.854 20.629 20.605 Problem-solving coping (0.878) PSC1 PSC2 PSC3 PSC4 0.830 0.817 0.808 0.756 Fixed 17.669 17.417 15.951 Emotion-focused coping (0.839) EFC1 EFC2 EFC3 EFC4 0.805 0.866 0.721 0.635 Fixed 16.479 14.048 12.142 Job satisfaction (0.932) JS1 JS2 JS3 JS4 JS5 0.853 0.865 0.860 0.868 0.772 Fixed 21.377 21.174 21.511 17.760 CCRa AVEb 0.877 0.725 0.863 0.691 0.827 0.672 – 0.826 0.693 0.880 0.745 0.814 0.632 0.701 0.576 0.896 0.713 Emotional intelligence 1659 Notes: a CCR ⫽ composite construct reliability; bAVE ⫽ average variance extracted; 2 ⫽ 954.767 (df ⫽ 467) p ⬍ 0.001; 2/df ⫽ 2.044; goodness-of-fit Index (GFI) ⫽ 0.864; normed fit index (NFI) ⫽ 0.899; Tucker Lewis index (TLI) ⫽ 0.938; comparative fit index (CFI) ⫽ 0.945; incremental fit index (IFI) ⫽ 0.945; root square error of approximation (RMSEA) ⫽ 0.053; root mean square residual (RMR) ⫽ 0.068 Table II. Confirmatory factor analysis and reliabilities Table III. Correlation analysis, means, and standard deviations 1 ⫺0.09 ⫺0.22** ⫺0.21** ⫺0.07 ⫺0.09 ⫺0.17** ⫺0.13* ⫺0.09 ⫺0.11* ⫺0.14** ⫺0.11* 1 ⫺0.09 0.41** 0.02 ⫺0.06 ⫺0.01 0.03 0.08 0.10 ⫺0.04 0.08 2 1 0.39** 0.11* 0.09 0.20** 0.05 0.09 0.18** 0.21** 0.20** 3 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 0.10 1 0.52** 0.43** ⫺0.06 0.02 0.59** 1 0.52** 0.54** ⫺0.11* 0.14** 0.46** 0.52** 1 0.49** 0.50** ⫺0.12* 0.08 0.31** 0.44** 0.46** 1 0.37** 0.38** ⫺0.07 0.12* 0.53** 0.55** 0.49** 0.39** 1 0.18** 0.43** 0.56** 0.51** 0.38** 0.56** 1 0.03 ⴚ0.08 ⴚ0.18** ⴚ0.09 ⴚ0.12* ⴚ0.20** ⴚ0.13* 1 0.23** 0.38** 0.45** 0.52** 0.42** 0.49** 0.52** ⴚ0.17* 4 1 0.37** 0.44** 0.51** 0.41** 12 – – – – 4.81 ⫾ 1.12 4.90 ⫾ 1.08 4.87 ⫾ 1.13 4.53 ⫾ 1.24 5.16 ⫾ 1.13 4.87 ⫾ 1.09 3.41 ⫾ 1.25 4.55 ⫾ 1.08 Mean ⫾ SD a a Notes: SD ⫽ standard deviation; all variables were measured on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree); OEA ⫽ others’ emotion appraisal; SEA ⫽ self-emotion appraisal; UOE, use of emotion; ROE ⫽ regulation of emotion; CAC ⫽ cognitive-appraisal coping; PSC ⫽ problem-solving coping; EFC ⫽ emotion-focused coping; JS ⫽ job satisfaction; * p ⬍ 0.05; ** p ⬍ 0.01; italic data ⫽ marker-variable partial correlation analysis (job engagement, mean ⫽ 3.45, SD ⫽ 1.45); Bold data ⫽ squared correlations 1. Gender 2. Age 3. Education level 4. Tenure 5. OEA 6. SEA 7. UOE 8. ROE 9. CAC 10. PSC 11. EFC 12. JS 1 1660 Construct Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) IJCHM 28,8 general characteristics of the respondents had no significant effect on this causal relationship. 4.3 Structural equation modeling Structural equation modeling (SEM) was demonstrated to analyze the hypotheses and the proposed model. The model fit was data well (2 ⫽ 825.109; df ⫽ 463; p ⬍ 0.001; GFI ⫽ 0.884; NFI ⫽ 0.912; CFI ⫽ 0.959; and RMSEA ⫽ 0.046). The value of the normed 2 was 1.782, which was below the cut-off criterion of 3 (Hair et al., 2006). Table IV and Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) Hypothesized path (stated as alternative hypothesis) Standardized coefficients t-value 1661 Results H1: EI ¡ cognitive-appraisal coping H1a OEA ¡ CAC H1b SEA ¡ CAC H1c UOE ¡ CAC H1d ROE ¡ CAC 0.291 0.263 0.194 0.112 4.532*** 3.275*** 3.216** 1.922* Supported Supported Supported Supported H2: EI ¡ problem-solving coping H2a OEA ¡ PSC H2b SEA ¡ PSC H2c UOE ¡ PSC H2d ROE ¡ PSC 0.060 0.391 0.266 0.102 0.912ns 5.099*** 4.141*** 1.693ns Rejected Supported Supported Rejected H3: EI ¡ emotion-focused coping H3a OEA ¡ EFC H3b SEA ¡ EFC H3c UOE ¡ EFC H3d ROE ¡ EFC 0.056 ⫺0.233 0.033 ⫺0.059 0.669ns ⫺2.509* 0.414ns ⫺0.766ns Rejected Supported Rejected Rejected H4: Coping style ¡ job satisfaction H4a CAC ¡ JS H4b PSC ¡ JS H4c EFC ¡ JS 0.196 0.255 ⫺0.085 2.837** 3.631*** ⫺1.796ns Supported Supported Rejected H5: EI ¡ job satisfaction H5a OEA ¡ JS H5b SEA ¡ JS H5c UOE ¡ JS H5d ROE ¡ JS 0.020 ⫺0.017 0.240 0.127 0.291ns ⫺0.212ns 3.631*** 2.161* Rejected Rejected Supported Supported Goodness-of-fit statistics Emotional intelligence 2(463) ⫽ 825.109 (p ⬍ 0.001) 2/df ⫽ 1.782 GFI ⫽ 0.884 NFI ⫽ 0.912 CFI ⫽ 0.959 RMSEA ⫽ 0.046 Notes: GFI ⫽ goodness-of-fit index; NFI ⫽ normed fit index; CFI ⫽ comparative fit index; RMSEA ⫽ root mean square error of approximation; EI ⫽ emotional intelligence; OEA ⫽ others’ emotion appraisal; SEA ⫽ self-emotion appraisal; UOE ⫽ use of emotion; ROE ⫽ regulation of emotion; CAC ⫽ Table IV. cognitive-appraisal coping; PSC ⫽ problem-solving coping; EFC ⫽ emotion-focused coping; JS ⫽ job Structural parameter estimates satisfaction; * p ⬍ 0.05; ** p ⬍ 0.01; *** p ⬍ 0.001 IJCHM 28,8 Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) 1662 Figure 2. SEM with parameter estimates Figure 2 show the standardized coefficients and t-values for all relationships in the SEM. 4.3.1 Relationship between emotional intelligence and stress-coping style. To examine how employees’ EI affects cognitive-appraisal coping styles, H1 was verified and accepted. Specifically, among the elements of employees’ EI, OEA ( ⫽ 0.291; t ⫽ 4.532; p ⬍ 0.001), SEA ( ⫽ 0.263; t ⫽ 3.275; p ⬍ 0.001), UOE ( ⫽ 0.194; t ⫽ 3.216; p ⬍ 0.01) and ROE ( ⫽ 0.112; t ⫽ 1.922; p ⬍ 0.05) had positive effects on cognitive-appraisal coping style. H2 was partially supported (i.e. employees’ EI has a significant effect on problem-solving style). SEA ( ⫽ 0.391; t ⫽ 5.099; p ⬍ 0.001) and UOE ( ⫽ 0.266; t ⫽ 4.141; p ⬍ 0.001) had positive effects on problem-solving style, whereas OEA ( ⫽ 0.060; t ⫽ 0.912; p ⬎ 0.05) and ROE ( ⫽ 0.102; t ⫽ 1.693; p ⬍ 0.05) did not. H3 was partially supported as well (i.e. employees’ EI has a significant effect on emotion-focused style). SEA ( ⫽ -.233; t ⫽ ⫺2.509; p ⬍ 0.05) had a significant negative effect on emotion-focused style, whereas OEA ( ⫽ 0.056; t ⫽ 0.669; p ⬎ 0.05), UOE ( ⫽ 0.033; t ⫽ 0.414; p ⬎ 0.05) and ROE ( ⫽ ⫺0.059; t ⫽ ⫺0.766; p ⬍ 0.05) did not. 4.3.2 Relationship between stress-coping style and job satisfaction. Employees’ coping styles had a significant effect on job satisfaction; therefore, H4 was also partially supported. Specifically, among employees’ stress-coping style elements, problem-solving coping ( ⫽ 0.255; t ⫽ 3.631; p ⬍ 0.001) and cognitive-appraisal coping ( ⫽ 0.196; t ⫽ 2.837; p ⬍ 0.01) had positive effects, whereas emotion-focused coping ( ⫽ ⫺0.085; t ⫽ ⫺1.796; p ⬎ 0.05) did not. 4.3.3 Relationship between emotional intelligence and job satisfaction. H5 (i.e. employees’ EI has a significant effect on job satisfaction) was also partially accepted. UOE ( ⫽ 0.240; t ⫽ 3.85; p ⬍ 0.001) and ROE ( ⫽ 0.127; t ⫽ 2.161; p ⬍ 0.05) had a significant effect on job satisfaction, whereas OEA ( ⫽ 0.020; t ⫽ 0.291; p ⬎ 0.05) and SEA ( ⫽ ⫺0.017; t ⫽ ⫺0.212; p ⬎ 0.05) did not. 5. Conclusion and implication 5.1 Conclusions This study sought to explore the effects of hospitality employees’ EI on stress-coping styles and job satisfaction. EI is divided into four dimensions: OEA, UOE, SEA and ROE. This study observed that all dimensions – OEA, SEA, ROE and UOE in order of Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) influence – have a significant positive effect on cognitive-appraisal coping style (Moradi et al., 2011; Sakloske et al., 2012; Vergara et al., 2010). Thus, all four EI sub-factors have positive effects on coping when using cognitive-appraisal styles in stressful situations. In other words, as employees understand others’ emotions and control their emotions while effectively utilizing and adjusting their emotions, they can also cope with stress using cognitive-appraisal styles, as all other EI sub-factors play a positive role in the cognitive-coping styles. Another finding was that SEA and UOE in employees’ EI have significant positive effects on the problem-solving coping style. These findings support previous studies (Noorbakhsh et al., 2010; Por et al., 2011). The results of this study indicated that EI regarding the ability to perceive self-emotions efficiently while using emotions induced problem-solving coping behaviors. In particular, EI in SEA was the most important factor in increasing problem-solving coping; moreover, SEA had greater influence on problem-solving coping than UOE did. Unlike other factors, however, ROE and OEA had no significant effects. Thus, ROE and OEA are not important factors in problem-solving coping styles in stressful situations. In other words, the results can be interpreted such that individuals’ abilities to understand, control and adjust their emotions are more advantageous in coping with stress by solving problems. In addition, the influence of SEA on the emotion-focused coping style was negatively significant (Davis and Humphrey, 2012; MacCann et al., 2011; Moradi et al., 2011). Conversely, OEA, UOE and ROE had no significant effects on emotion-focused coping style. Thus, EI with regard to understanding one’s emotions negatively affects styles to emotionally cope with stressful situations. In other words, employees with excellent understanding and control of their emotions were not likely to cope with stress using emotional styles. Consequently, SEA was shown to be the EI variable that would most affect all styles of coping with stress. The assumed reason for this finding is that only those who can recognize and comprehend their own emotions can understand others’ emotions, thereby utilizing and regulating emotions. Regarding the link between stress-coping styles and job satisfaction, the influence of problem-solving coping and cognitive-appraisal coping on job satisfaction was positively significant. These results are in line with the studies conducted by Golbasi et al. (2008), Reissner et al. (2008) and Welbourne et al. (2007); an employee’s positive stress-coping styles (problem-solving coping and cognitive-appraisal coping) induce his or her job satisfaction. The UOE and ROE of hospitality employees’ EI were noted to have a significant effect on job satisfaction, whereas OEA and SEA among EI dimensions did not. This result can be interpreted as a context similar to the fact that UOE significantly affected not only positive styles for coping with stress (cognitive coping and problem-solving coping) but also emotional coping, a negative style for coping with stress. This result was partially consistent with that of Mayer and Salovey (1995), indicating that employees with higher EI have better control of self-emotion, which leads to positive work satisfaction. 5.2 Theoretical implications This study developed a theoretical foundation for the cause-and-effect relationships among EI, stress-coping styles and job satisfaction recognized by hospitality employees. Although, as predicted, employees’ EI was shown to affect stress-coping styles and job satisfaction, this study also examined the effect of employees’ coping styles on job satisfaction. However, this study is significant because it investigates Emotional intelligence 1663 IJCHM 28,8 Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) 1664 sub-factors in EI and examines the relationship between stress-coping styles and job satisfaction in hospitality companies. The present study demonstrated that enhancing employees’ EI through education and reflecting the importance of EI when selecting talented persons for efficient personnel management could have positive results that enhance organizations’ effectiveness. In particular, the present study showed that employees with high EI cope with stressful situations using positive styles and, consequently, experience higher job satisfaction. The theoretical implications of this finding are important. This result showed that, although rational approaches to solving problems with the brain were pursued in past personnel management practices, EI-oriented approaches to employee management are worth considering. In particular, the present study verified that coping styles in stressful situations experienced during the performance of jobs varied according to employees’ EI. A sub-result showed that the SEA of employees’ EI significantly affected all types of styles used to cope with stress. Thus, employees’ ability to efficiently overcome stressful situations is determined by how well they understand and control their emotions. Moreover, as an element of EI, SEA is the most closely related to strategies for coping with stress. In addition, the results showed that EI plays an efficient role in helping individuals take appropriate actions to solve problems and cope with problems using active styles (Caruso and Salovey, 2004). In particular, SEA not only has a significant positive effect on stress-coping styles (cognitive-appraisal coping and problem-solving coping) but also is considered to be a unique EI variable that can negatively affect the decrease of the stress-coping styles (emotion-focused coping). This means that employees who control their emotions well but perhaps lack the ability to utilize their emotions and understand others’ emotions might have a higher probability of not coping with stress using emotional styles. Therefore, corporations should improve their employees’ ability to understand and utilize their emotions. As a result, one can utilize one’s emotions and understand others’ emotions only when one can control one’s own emotions. In particular, in the case of the hospitality industry, employees’ EI has all the more special meanings owing to their continuous emotional labor. EI also showed a significant relationship with job satisfaction. Among the many factors involved in EI, UOE and ROE were shown to affect job satisfaction directly. Thus, as employees have a better ability to utilize and control their emotions, they experience more job satisfaction. Therefore, it is assumed that in the representative hospitality industry where direct communications with customers are frequent (Choi et al., 2014; Kang and Hyun, 2012), the regulation or utilization of momentary emotions not only is important but also affects job satisfaction. In other words, employees who utilize emotions well even when they face negative emotions, such as stress, while performing their jobs can positively affect their job satisfaction by efficiently controlling their emotions and seeking effective coping styles. As employees perform their jobs in every situation, instead of simply understanding or utilizing their own or others’ emotions, the study results show that EI is the ability to regulate and manage emotions so that one can quickly solve problems without being embarrassed or excited in problematic situations. 5.3 Practical implications As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, considering that individual employees’ EI is not fixed like an inherent disposition but is similar a trait that can be developed (Goleman, 1998), outstanding internal marketing measures can be sought by Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) utilizing this study’s results with hospitality companies’ managers. First, tangible tools (test of EI index) should be procured that can be utilized to select employees with high EI or a HRM recruit with potentially outstanding EI ability. Furthermore, for those already working in a company, systematic training and education programs should be enacted to improve their EI. For example, employees’ potential EI should be developed using coaching or mentoring, and through simulation education, which may occur in various virtual service situations, coping abilities using EI in a sudden service situation may be able to be learned. In addition, to form bond of sympathy among organizational employees, opportunities to share opinions about organizational culture should be frequently created, employees’ emotions should be respected and employees’ own changes should be induced. Moreover, considering that senior leaders could influence junior employees’ positive work attitude, programs in which senior managers, rather than junior employees (Pastor, 2014), might participate should be provided. In addition, as the most important factor in EI requires understanding and identifying one’s own emotions, as inferred from this study’s results, professional counselors should be available within an organization to help employees understand and control their emotions by themselves. In addition, watching movies and musicals should be recommended for improving cultural emotions of employees, and methods to stimulate employees’ emotions through book lending and watching art galleries or exhibitions should be created. Through such efforts, the ability to demonstrate emotional understanding and empathy, as well as to adjust and control the negative emotions, can be improved via suitable training program development to maximize employees’ EI within an organization, thereby preparing them to cope with stressful situations flexibly while contributing to the improvement of their job performance. Ultimately, this study emphasized on the simple fact that the development and management of EI, whatever it might be, is needed to improve employees’ efforts and behavior for organizational enhancement. Following this trend, this study’s results support the introduction of emotional management in hospitality companies. The results also demonstrated that employees’ job satisfaction varied according to the styles they used to cope with stressful situations. In particular, it was verified that employees who used positive methods (cognitive coping and problem-solving coping) showed high job satisfaction. Employees have a desire to cope with stressful situations using their own methods (Pearlin and Schooler, 1978), and job satisfaction is determined by the degree of actively coping with stressful situations. In particular, given that foodservice employees are likely to be exposed to stressful situations because of their frequent contact with customers, they will be dissatisfied with their jobs if this stress is not efficiently managed or relieved. Methods to cope with stressful situations are assumed to be meaningful at the business level. The results also suggested that to induce employees’ positive actions, it is necessary to encourage them to implement active job-oriented coping strategies. To this end, foodservice businesses should seek methods to implement appropriate education to prepare their employees to cope with stress. To inform their employees, such education should include methods to effectively cope with and overcome the stress they face, as well as strategies to improve employees’ job satisfaction. The results of this study, which indicate that hospitality companies can increase employees’ job satisfaction by enhancing their employees’ EI, suggest detailed and practical Emotional intelligence 1665 Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) IJCHM 28,8 alternatives to HRM, as employees’ EI can bring positive outcomes to both organizations (job satisfaction) and employees (efficient stress-coping). Hospitality employees’ EI is significant in terms of organizational performance (e.g. job satisfaction and positive stress-coping behavior). 1666 5.4 Limitations and future research Despite the contributions made by this study, several limitations need to be addressed. First, the generalization of the results might be limited, because the sample comprised employees of deluxe hotels and family restaurants in South Korea; as such, the study’s subjects cannot be evaluated to be typical of the hospitality industry. Second, the questionnaire’s contents, which were used to measure EI and stress-coping styles, were based on a general company and not specifically on a company in the hospitality industry. Thus, these results do not apply to the entire hospitality industry. Third, this study did not meditate a sufficient number of variables of individual differences that might influence EI. Also, CMB error was somewhat validated through exploratory factor analysis (EFA), but the possibility for error is still present. In addition, investigating the moderate effects of cause-and-effect relationships in employees’ characteristics (demographic and job-related) could lead to specific recommendations. As EI can differ according to culture and individuals’ characteristics (Gökçen et al., 2014; Koveshnikov et al., 2014; Wechtler et al., 2014), we believe that verifying its controlling role in general aspect can provide management side with practical and useful implications. Even comparisons through analyzing the moderating effect in this causality targeting general service-business employees and hospitality company employees in future research will be useful for hospitality company operators. This can be further developed into a study which puts emphasis on the EI among the employees in the hospitality industry who are required to frequently perform emotional labor by comparing EI between ordinary firm employees and hospitality industry employees. Finally, this study relied exclusively on the job satisfaction level as the final dependent variable; therefore, future studies should examine additional inputs of variables that can define an employee’s intention to leave a job, such as their job performance or job commitment. This will be able to suggest meaningful research results in that it can study the EI sub-factors that affect the overall work attitude of the employees. References Aghdasi, S., Kiamanesh, A.R. and Ebrahim, A.N. (2011), “Emotional intelligence and organizational commitment: testing the mediatory role of occupational stress and job satisfaction”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 1965-1976. Aldwin, C.M. and Revenson, T.A. (1987), “Does coping help? A re-examination of the relation between coping and mental health”, Journal of Personality and Society Psychology, Vol. 53 No. 2, pp. 347-348. Amber Raza, M.A.K. and Ali, U. (2007), “Occupational stress and coping mechanism to increase job satisfaction among supervisors at Karachi pharmaceuticals”, Market Forces, Vol. 2 No. 4, pp. 1-23. Anderson, J.C. and Gerbing, D.W. (1988), “Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 103 No. 3, pp. 411-423. Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) Armstrong-Stassen, M. (2004), “The influence of prior commitment on the reactions of layoff survivors to organizational downsizing”, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 46-60. Austin, E.J., Saklofske, D.H. and Mastoras, S.M. (2010), “Emotional intelligence, coping and exam-related stress in Canadian undergraduates students”, Australian Journal of Psychology, Vol. 62 No. 1, pp. 42-50. Bande, B., Fernandez-Ferrin, O., Varela, J.A. and Jaramillo, F. (2015), “Emotions and salesperson propensity to leave: the effects of emotional intelligence and resilience”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 44 No. 1, pp. 142-153. BhuIiar, N., Schutte, N.S. and Malouff, J.M. (2012), “Trait emotional intelligence as a moderator of the relationship between psychological distress and satisfaction with life”, Individual Differences Research, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 19-26. Billings, A.G. and Moos, R.H. (1981), “The role of coping response and social resources in attenuating the stress of life event”, Journal of Behavioral Medicine, Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 139-157. Billings, A.G. and Moos, R.H. (1984), “Coping, stress and social resources among adults with unipolar depression”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 46 No. 4, pp. 877-891. Brackett, M.A., Palomera, R., Mojsa-Kaja, J., Reyes, M.R. and Salovey, P. (2010), “Emotion-regulation ability, burnout, and job satisfaction among British secondary-school teachers”, Psychology in the Schools, Vol. 47 No. 4, pp. 406-417. Brown, S.P. (1996), “A meta-analysis and review or organizational research on job involvement”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 120 No. 2, pp. 235-255. Callan, V.J., Terry, D.J. and Schweitzer, R. (1994), “Coping resources, coping strategies and adjustment to organizational change: direct or buffering effects?”, Work and Stress, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 372-383. Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D. and Klesh, J. (1983), “Assessing the attitudes and perceptions of organizational member”, in Seashore, S., Lawler, E., Mirvis, P. and Cammann, C. (Eds), Assessing Organizational Change: A Guide to Methods, Measures, and Practices, Wiley, New York, NY. Cartwright, S. and Pappas, C. (2008), “Emotional intelligence, its measurement and implications for the workplace”, International Journal of Management Review, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 149-171. Caruso, D.R. and Salovey, P. (2004), The Emotionally Intelligent Manager, Jossey-Bass, CA. Carver, C., Pozo, C., Harris, S., Noriega, V., Scheier, M. and Robinson, D. (1993), “How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: a study of women with early stage breast cancer”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 65 No. 2, pp. 375-390. Çekmecelioğlu, H.G., Günsel, A. and Ulutaş, T. (2012), “Effects of emotional intelligence on job satisfaction: an empirical study on call center employees”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 58 No. 12, pp. 363-369. Cha, J.M., Cichy, R.F. and Kim, S.H. (2008), “The contribution of emotional intelligence to social skills and stress management skills among automated foodservice industry executives”, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 15-31. Chen, C.K., Lin, C., Wang, S.H. and Hou, T.H. (2009), “A study of job stress, stress coping strategies, and job satisfaction for nurses working in middle-level hospitality operating rooms”, Journal of Nursing Research, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 199-211. Choi, C.H., Kim, T.G., Lee, G.H. and Lee, S.K. (2014), “Testing the stressor-strain-outcome model of customer-related social stressors in predicting emotional exhaustion, customer orientation Emotional intelligence 1667 IJCHM 28,8 Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) 1668 and service recovery performance”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 272-285. Chu, K.H., Baker, M.A. and Murrmann, S.K. (2012), “When we are onstage, we smile: the effects of emotional labor on employee work outcomes”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 906-915. Ciarrochi, J., Deane, F. and Anderson, S. (2002), “Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between stress and mental health”, Personality and Individual Difference, Vol. 32 No. 2, pp. 197-209. Cichy, R.F., Cha, J.M. and Kim, S.H. (2008), “Private club leaders’ emotional intelligence: development and validation of a new measure of emotional intelligence”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, Vol. 31 No. 1, pp. 39-55. Collins, S. (2008), “Statutory social workers: stress, job satisfaction, coping, social support and individual differences”, British Journal of Social Work, Vol. 38 No. 6, pp. 1173-1193. Cote, S. and Miners, C.T.H. (2006), “Emotional intelligence, cognitive intelligence and job performance”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 51 No. 1, pp. 1-28. Daus, C.S. and Ashkanasy, N.M. (2005), “The case for the ability-based model of emotional intelligence in organizational behavior”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 26 No. 4, pp. 453-466. Davis, S.K. and Humphrey, N. (2012), “The influence of emotional intelligence on coping and mental health in adolescence: divergent roles for trait and ability EI”, Journal of Adolescence, Vol. 35 No. 5, pp. 1369-1379. Day, A.L. and Carroll, S.A. (2004), “Using an ability-based measure of emotional intelligence to predict individual performance, group performance, and group citizenship behaviours”, Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 36 No. 6, pp. 1443-1458. Dickey, H., Watson, V. and Zangelidis, A. (2011), “Job satisfaction and quit intentions of offshore workers in the UK North Sea oil and gas industry”, Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 58 No. 5, pp. 607-633. Downey, L.A., Johnston, P.J., Hansen, K., Birney, J. and Stough, C. (2010), “Investigating the mediating effects of emotional intelligence and coping on problem behaviours in adolescents”, Australian of Psychology, Vol. 62 No. 1, pp. 20-29. Fariselli, L., Freedman, J., Ghini, M. and Valentini, F. (2008), “Stress, emotional intelligence, and performance in healthcare: the emotional intelligence network”, White Paper, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 1-11. Folkman, S. and Lazarus, R.S. (1980), “An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample”, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 21 No. 3, pp. 219-232. Folkman, S., Lazarus, R.S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., Delongis, A. and Gruen, R.J. (1986), “Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 50 No. 5, pp. 992-1003. Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981), “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50. Gil, I., Berenguer, G. and Cervera, A. (2008), “The roles of service encounters, service value, and job satisfaction in achieving customer satisfaction in business relationship”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 37 No. 8, pp. 921-939. Gohm, C., Corser, G. and Dalsky, D. (2005), “Emotional intelligence under stress: useful, unnecessary, or irrelevant?”, Personality and Individual Difference, Vol. 39 No. 6, pp. 1017-1028. Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) Gökçen, E., Furnham, A., Mavroveli, S. and Petrides, K.V. (2014), “A cross-cultural investigation of trait emotional intelligence in Hong Kong and the UK”, Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 65 No. 1, pp. 30-35. Golbasi, Z., Kelleci, M. and Dogan, S. (2008), “Relationships between coping strategies, individual characteristics and job satisfaction in a sample of hospital nurses: cross-sectional questionnaire survey”, International Journal of Nursing Studies, Vol. 45 No. 12, pp. 1800-1806. Goleman, D. (1995), Emotional Intelligence, Bantam Books, New York, NY. Goleman, D. (1998), Working with Emotional Intelligence, Bantam Books, New York, NY. Gooty, J., Gavin, M.B., Ashkanasy, N.M. and Thomas, J.S. (2014), “The wisdom of letting go and performance: the moderating role of emotional intelligence and discrete emotions”, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 87 No. 2, pp. 392-413. Guleryuz, G., Guney, S., Aydin, E.M. and Asan, O. (2008), “The mediating effect of job satisfaction between emotional intelligence and organizational commitment of nurses: a questionnaire survey”, International Journal of Nursing Studies, Vol. 45 No. 11, pp. 1625-1635. Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E. and Tatham, R.L. (2006), Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings, 6th ed., Prentice-Hall, NJ. Harman, H.H. (1967), Modern Factor Analysis, University of Chicago Press, IL. Hon, A.H.Y. and Lu, L. (2010), “The mediating role of trust between expatriate procedural justice and employee outcomes in Chinese industry”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 29 No. 4, pp. 669-676. Houghton, J.D., Wu, J., Godwin, J.L., Neck, C.P. and Manz, C.C. (2012), “Effective stress management: a model of emotional intelligence, self-leadership, and student stress coping”, Journal of Management Education, Vol. 36 No. 2, pp. 220-238. Hunt, N. and Evans, D. (2004), “Predicting traumatic stress using emotional intelligence”, Behavioral Research and Therapy, Vol. 42 No. 7, pp. 791-798. Hur, Y.H., Berg, P.T. and Wilderom, C.P.M. (2011), “Transformational leadership as a mediator between emotional intelligence and team outcomes”, The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 22 No. 4, pp. 591-603. Ivancevich, J., Olelelns, M. and Matterson, M. (1997), Organizational Behavior and Management, Irwin, Sydney. Johnson, H.A.M. and Spector, P.E. (2007), “Service with a smile: do emotional intelligence, gender, and autonomy moderate the emotional labor process?”, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 319-333. Jung, H.S. and Yoon, H.H. (2012), “The effects of employees’ emotional intelligence on counterproductive behavior and organizational citizenship behavior”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 369-378. Kafetsios, K. and Zampetakis, L.A. (2008), “Emotional intelligence and job satisfaction: testing the mediatory role of positive and negative affective at work”, Personality Individual Difference, Vol. 44 No. 3, pp. 712-722. Kang, J.H. and Hyun, S.H.S. (2012), “Effective communication styles for the customer-oriented service employee: inducing dedicational behaviors in luxury restaurant patrons”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 772-785. Kim, H.J. and Agrusa, J. (2011), “Hospitality service employees’ coping style: the role of emotional intelligence, two basic personality traits, and socio-demographic factor”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 30 No. 3, pp. 588-598. Emotional intelligence 1669 IJCHM 28,8 Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) 1670 Kim, Y.H. (2010), “The effects of foodservice employee‘s job stressors on job satisfaction and turnover intention focused on social support and coping strategies”, Korean Journal of Culinary Research, Vol. 16 No. 4, pp. 206-219. Ko, W.H. (2012), “The relationships among professional competence, job satisfaction and career development confidence for chefs in Taiwan”, Tourism Management, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 1004-1011. Koveshnikov, A., Wechtler, H. and Dejoux, C. (2014), “Cross-curtural adjustment of expatriates: the role of emotional intelligence and gender”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 49 No. 3, pp. 362-371. Labo, T.P. (2005), “The relationship between leader-member exchange (LMX) and emotional intelligence (EI) in public schools: a regression approach”, Doctoral dissertation, Barry University, Adrian Dominican School of Education, Miami. Langhorn, S. (2004), “How emotional intelligence can improve management performance”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 16 No. 4, pp. 220-230. Law, K.S., Wong, C.S., Huang, G.H. and Li, X. (2008), “The effects of emotional intelligence on job performance and life satisfaction for the research and development scientists in China”, Asia Pacific Journal Management, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 51-69. Lazarus, R. (1998), The Life and Work of an Eminent Psychologist: Autobiography of Richard S. Lazarus, Springer, New York, NY. Lazarus, R. and Folkman, S. (1984), Stress, Appraisal and Coping, Springer, New York, NY. Lee, J.H. and Ok, C. (2012), “Reducing burnout and enhancing job satisfaction: critical role of hotel employees’ emotional intelligence and emotional labor”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 31 No. 4, pp. 1101-1112. Lindell, M.K. and Whitney, D.J. (2001), “Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 86 No. 1, pp. 114-121. Littrell, J. and Beck, E. (2001), “Predictors of depression in a sample of African-American homeless men: identifying effective coping strategies given varying levels of daily stressors”, Community Mental Health Journal, Vol. 37 No. 1, pp. 15-29. Locke, E. (1969), “What is job satisfaction?”, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 309-336. Lope, P.N., Grewal, D., Kadis, J., Gall, M. and Salovey, P. (2006), “Evidence that emotional intelligence is related to job performance and affect and attitudes at work”, Psicothema, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 132-138. MacCann, C., Fogarty, G.J., Zeidner, M. and Roberts, R.D. (2011), “Coping mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and academic achievement”, Contemporary Educational Psychology, Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 60-70. Mayer, J.D. and Salovey, P. (1995), “Emotional intelligence and the construction and regulation of feelings”, Applied and Preventive Psychology, Vol. 4 No. 3, pp. 197-208. Mayer, J.D. and Salovey, P. (1997), What is Emotional Intelligence? Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Educators, Basic Books, New York, NY, pp. 3-31. Mayer, J.D., Salovey, P. and Caruso, D.R. (2002), MSCEIT User’s Manual, Multi-Health Systems, Toronto. Meichenbaum, D. (1985), Stress Inoculation Training, Pergamon, Oxford. Michaels, E., Handfield-Jones, H. and Axelrod, B. (2001), The War for Talent, Harvard Business Review Press, MA. Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) Mikolajczak, M., Nelis, D., Hansenne, M. and Quiodback, J. (2008), “If you can regulate sadness, you can probably regulate shame: associations between trait emotional intelligence, emotion regulation and coping efficiency across discrete emotions”, Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 44 No. 6, pp. 1356-1368. Min, J.C.H. (2012), “A short-form measure for assessment of emotional intelligence for tour guides: development and evaluation”, Tourism Management, Vol. 33 No. 1, pp. 155-167. Moradi, A., Pishva, N., Ehsan, H.B., Hadadi, P. and Pouladi, F. (2011), “The relationship between coping strategies and emotional intelligence”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 30 No. 1, pp. 748-751. Mousavi, S.H., Yarmohammadi, S., Norsrat, A.B. and Tarasi, Z. (2012), “The relationship between emotional intelligence and job satisfaction of physical education teachers”, Annals of Biological Research, Vol. 3 No. 2, pp. 780-788. Noorbakhsh, S.N., Besharat, M.A. and Zarei, J. (2010), “Emotional intelligence and coping styles with stress”, Procedia Social and Behavioral Science, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 818-822. Nunnally, J. (1978), Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. Oakland, S. and Ostell, A. (1996), “Measuring coping: a review and critique”, Human Relations, Vol. 49 No. 2, pp. 133-155. Palmer, B., Donaldson, C. and Stough, C. (2002), “Emotional intelligence and life satisfaction”, Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 33 No. 7, pp. 1091-1100. Park, C. and Adler, N. (2003), “Coping styles as a predictor of health and well-being across the first year of medical school”, Health Psychology, Vol. 22 No. 6, pp. 627-631. Pastor, I. (2014), “Leadership and emotional intelligence: the effect on performance and attitude”, Procedia Economics and Finance, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 985-992. Pau, A. and Croucher, R. (2003), “Emotional intelligence and perceived stress in dental undergraduates”, Journal of Dental Education, Vol. 67 No. 9, pp. 1023-1028. Pearlin, L.I. and Schooler, C. (1978), “The structure of coping”, Journal of Health Society Behavior, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 2-21. Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y. and Podsakoff, N.P. (2003), “Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88 No. 5, pp. 879-903. Por, J., Barriball, L., Fitzpatrick, J. and Roberts, J. (2011), “Emotional intelligence: its relationship to stress, coping, well-being and professional performance in nursing students”, Nurse Education Today, Vol. 31 No. 8, pp. 855-860. Prentice, C. and King, B.E.M. (2013), “Emotional intelligence and adaptability: service encounters between casino hosts and premium players”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 287-294. Psilopanagioti, A., Anagnostopoulos, F., Mourtou, E. and Niakas, D. (2012), “Emotional intelligence, emotional labor, and job satisfaction among physicians in Greece”, BMC Health Service Research, Vol. 12 No. 463, pp. 1-12. Reissner, V., Baune, B., Votsidi, V., Schifano, F., Room, R., Stohler, R., Schwarzer, C. and Scherbaum, N. (2008), “Burnout, coping and job satisfaction in service staff treating opioid addicts: from Athens to Zurich”, European Psychiatry, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. S81-S191 (P0025), Abstracts for Poster Session 1. Rogers, T., Qualter, P., Phelps, G. and Gardner, K. (2006), “Belief in the paranormal, coping and emotional intelligence”, Personality and Individual Difference, Vol. 41 No. 6, pp. 1089-1115. Emotional intelligence 1671 IJCHM 28,8 Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) 1672 Sakloske, D.H., Austin, E.J., Galloway, J. and Davidson, K. (2007), “Individual difference correlates of health-related behaviors: preliminary evidence for links between emotional intelligence and coping”, Personality and Individual Difference, Vol. 42 No. 3, pp. 491-502. Sakloske, D.H., Austin, E.J., Mastoras, S.M., Beaton, L. and Osborne, S.E. (2012), “Relationships of personality, affect, emotional intelligence and coping with student stress and academic success: different patterns of association for stress and success”, Learning and Individual Differences, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 251-257. Salovey, P., Bedell, B.T., Detweiler, J. and Mayer, J.D. (2000), “Current directions in emotional intelligence research”, in Lewis, M. and Haviland-Jones, J.M. (Eds), Handbook of Emotions, Guilford Press, New York, NY, pp. 504-520. Salovey, P., Mayer, J.D. and Caruso, D. (2002), “The positive psychology of emotional intelligence”, in Zinder, C.R. and Lopez, S.J. (Eds), The Handbook of Positive Psychology, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp. 159-171. Scott-Halsell, S., Blum, S.C. and Huffman, L. (2008), “From school desks to front desk: a comparison of emotional intelligence levels of hospitality undergraduate students to hospitality industry professional”, Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 3-13. Scott-Halsell, S., Shumate, S.R. and Blum, S. (2007), “Using a model of emotional intelligence domains to indicate transformational leaders in the hospitality Industry”, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 99-113. Shah, M. and Thingujam, N.S. (2008), “Perceived emotional intelligence and ways of coping among students”, Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, Vol. 34 No. 1, pp. 83-91. Shani, A., Uriely, N., Reichel, A. and Ginsburg, L. (2014), “Emotional labor in the hospitality industry: the influence of contextual factors”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 37 No. 2, pp. 150-158. Shimizu, T. and Nagata, S. (2003), “Relationship between coping skills and job satisfaction among Japanese fulltime occupational physicians”, Environment Health and Preventive Medicine, Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 118-123. Slaski, M. and Cartwright, S. (2003), “Emotional intelligence training and its implications for stress, health, and performance”, Stress and Health, Vol. 19 No. 4, pp. 233-239. Song, W.I. (2008), “The relationship between stress coping strategy and job burnout of sport and leisure instructors”, Korean Alliance Health, Physical, Education, Recreation, Vol. 47 No. 1, pp. 263-269. Spagnoli, P., Caetano, A. and Santos, S.C. (2012), “Satisfaction with job aspects: do patterns change overtime”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 65 No. 5, pp. 609-616. Spector, P.E. (1985), “Measurement of human service staff satisfaction: development of the job satisfaction survey”, American Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 13 No. 6, pp. 693-713. Strutton, D. and Lumpkin, J. (1992), “Relationship between optimism and coping strategies in the work environment”, Psychology Report, Vol. 73 No. 3, pp. 1179-1186. Sy, T., Tram, S. and O’Hara, L.A. (2006), “Relation of employee and manager emotional intelligence to job satisfaction and performance”, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 68 No. 3, pp. 461-473. Vergara, M.B., Smith, N. and Keele, B. (2010), “Emotional intelligence, coping responses, and length of stay as correlates of acculturative stress among international university Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) students in Thailand”, Procedia Social and Behavioral Science, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 1498-1504. Wechtler, H., Koveshnikov, A. and Dejoux, C. (2014), “Just like a fine wine? Age, emotional intelligence, and cross-cultural adjustment”, International Business Review, In Press, Corrected Proof, Available online 11 October 2014. Weinberger, L.A. (2003), “An examination of the relationship between emotional intelligence, leadership style and perceived leadership effectiveness”, Doctoral dissertation, The Graduate School of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Welbourne, J.L., Eggerth, D., Hartley, T.A., Andrew, M.E. and Sanchez, F. (2007), “Coping strategies in the workplace: relationships with attributional style and job satisfaction”, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 70 No. 2, pp. 312-325. Wolfe, K. and Kim, H.J. (2013), “Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, and job tenure among hotel managers”, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 175-191. Wong, C.S. and Law, K.S. (2002), “The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: an exploratory study”, The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 243-274. Wons, A. and Barqiel-Matusiewicz, K. (2011), “The emotional intelligence and coping with stress among medical students”, Wiadomoœci Lekarskie, Vol. 64 No. 3, pp. 181-187. Further reading Karatepe, O.M. and Olugbade, O.A. (2009), “The effects of job and personal resource on hotel employees’ work engagement”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 28 No. 4, pp. 504-512. Matamala, A. (2011), “Work engagement as a mediator between personality and citizenship behavior”, The Graduate School, FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations, The Florida State University, Tallahassee. Organ, D.W. and Near, J.P. (1985), “Cognitive vs affect measures of job satisfaction”, International Journal of Psychology, Vol. 20 No. 1, pp. 241-254. Zeidner, M. and Shemesh, D.O. (2010), “Emotional intelligence and subjective well-being revisited”, Personality and Individual Difference, Vol. 48 No. 4, pp. 431-435. Appendix 1. Descriptive statistics of variables Emotional intelligence OEA1: I Always know my friends’ emotions from their behaviors (4.76 ⫾ 1.30). OEA2: I am good observer of others’ emotions (4.74 ⫾ 1.26). OEA3: I am sensitive to the feelings and emotions of others (4.88 ⫾ 1.18). OEA4: I have good understanding of the emotions of people around me (4.94 ⫾ 1.29). UOE1: I always set goals for myself and then try my best to achieve them (4.93 ⫾ 1.27). UOE2: I always tell myself I am a competent person (4.83 ⫾ 1.35). UOE3: I am a self-motivated person (4.75 ⫾ 1.26). UOE4: I always encourage myself to try my best (5.03 ⫾ 1.33). SEA1: I have a good sense of why I have certain feelings most of the time (4.75 ⫾ 1.23). SEA2: I have good understanding of my own emotions (4.91 ⫾ 1.24). SEA3: I really understand what I feel (4.99 ⫾ 1.25). SEA4: I always know whether I am happy or not (5.02 ⫾ 1.21). Emotional intelligence 1673 IJCHM 28,8 Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) 1674 ROE1: I am able to control my temper and handle difficulties rationally (4.70 ⫾ 1.36). ROE2: I am quite capable of controlling my own emotions (4.52 ⫾ 1.35). ROE3: I can always calm down quickly when I am very angry (4.50 ⫾ 1.43). ROE4: I have good control of my own emotions (4.49 ⫾ 1.42). Stress-coping styles CAC1: Tried to step back from the situation and be more objective (5.06 ⫾ 1.28). CAC2: Took things one step at a time (5.14 ⫾ 1.27). CAC3: Tried to step back from the situation and be more objective (5.25 ⫾ 1.26). CAC4: Prayed for guidance or strength (5.28 ⫾ 1.21). PSC1: Considered several alternatives for handling the problem (5.01 ⫾ 1.24). PSC2: Drew on my past experiences; I was in a similar situation before (4.88 ⫾ 1.25). PSC3: Tried to find out more about the situation (4.94 ⫾ 1.29). PSC4: Talked with spouse or other relative about the problem (4.84 ⫾ 1.34). EFC1: Sometimes took it out on other people when I felt angry or depressed (3.60 ⫾ 1.46). EFC2: Tried to reduce the tension by eating (smoking, drinking) more (3.43 ⫾ 1.50). EFC3: Kept my feelings to myself (3.34 ⫾ 1.51). EFC4: Got busy with other things in order to keep my mind off the problem (3.33 ⫾ 1.65). Job satisfaction JS1: I like the people I work with (4.58 ⫾ 1.50). JS2: My job is enjoyable (4.66 ⫾ 1.17). JS3: I like doing the things I do at work (4.72 ⫾ 1.20). JS4: In general, I like working here (4.60 ⫾ 1.22). JS5: All in all, I am satisfied with my job (4.39 ⫾ 1.41). Notes: (Mean ⫾ SD); SD ⫽ standard deviation; a all variables were measured on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree); OEA ⫽ others’ emotion appraisal; UOE ⫽ use of emotion; SEA ⫽ self-emotion appraisa; ROE ⫽ regulation of emotion); CAC ⫽ cognitive-appraisal coping; PSC ⫽ problem-solving coping); EFC ⫽ emotion-focused coping; JS ⫽ job satisfaction Emotional intelligence Appendix 2 Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) Variables OEA1 OEA2 OEA3 OEA4 SEA1 SEA2 SEA3 SEA4 UOE1 UOE2 UOE3 UOE4 ROE1 ROE2 ROE3 ROE4 CAC1 CAC2 CAC3 CAC4 PSC1 PSC2 PSC3 PSC4 EFC1 EFC2 EFC3 EFC4 JS1 JS2 JS3 JS4 JS5 Eigen values Variance F1 F2 F3 0.196 0.195 0.106 0.032 0.212 0.155 0.160 0.103 0.179 0.210 0.265 0.189 0.112 0.160 0.190 0.149 0.170 0.132 0.267 0.202 0.231 0.144 0.177 0.287 ⫺0.094 ⫺0.047 ⫺0.048 ⫺0.048 0.797 0.829 0.798 0.810 0.779 12.548 38.023 0.784 0.826 0.819 0.811 0.357 0.258 0.224 0.173 0.187 0.201 0.088 0.139 0.058 0.09 0.106 0.088 0.173 0.166 0.265 0.253 0.145 0.127 0.115 0.143 0.011 ⫺0.052 0.020 ⫺0.031 0.102 0.085 0.114 0.112 0.142 2.717 8.234 0.108 0.106 0.176 ⫺0.004 0.150 0.151 0.161 0.195 0.185 0.155 0.187 0.172 0.813 0.833 0.804 0.836 0.097 0.154 0.118 0.149 0.064 0.182 0.146 0.097 ⫺0.080 0.032 ⫺0.070 ⫺0.014 0.120 0.151 0.100 0.162 0.177 2.465 7.469 Factor loading F4 F5 0.181 0.162 0.213 0.163 0.122 0.207 0.171 0.184 0.145 0.092 0.158 0.183 0.164 0.120 0.037 0.106 0.797 0.825 0.754 0.740 0.241 0.165 0.169 0.188 ⫺0.063 ⫺0.069 ⫺0.152 0.056 0.170 0.115 0.180 0.167 0.074 2.088 6.328 0.180 0.138 0.128 0.130 0.132 0.189 0.154 0.191 0.783 0.790 0.739 0.744 0.183 0.162 0.101 0.152 0.141 0.143 0.133 0.197 0.133 0.139 0.142 0.209 ⫺0.038 ⫺0.017 0.063 ⫺0.071 0.191 0.140 0.219 0.158 0.123 1.638 4.964 F6 F7 F8 0.158 0.123 0.059 0.136 0.202 0.138 0.234 0.168 0.170 0.181 0.064 0.200 0.159 0.143 0.100 0.032 0.147 0.176 0.223 0.260 0.710 0.772 0.784 0.710 0.134 ⫺0.022 0.007 ⫺0.248 0.164 0.145 0.186 0.214 0.088 1.467 4.446 0.216 0.153 0.234 0.197 0.688 0.763 0.776 0.738 0.114 0.090 0.205 0.231 0.133 0.100 0.125 0.152 0.187 0.152 0.170 0.165 0.288 0.207 0.155 0.065 ⫺0.060 ⫺0.083 ⫺0.026 ⫺0.032 0.082 0.126 0.089 0.109 0.165 1.389 4.209 0.003 ⫺0.029 ⫺0.031 0.000 ⫺0.042 ⫺0.075 ⫺0.057 ⫺0.129 ⫺0.002 0.005 ⫺0.020 ⫺0.060 ⫺0.050 ⫺0.101 ⫺0.002 ⫺0.008 ⫺0.093 ⫺0.106 ⫺0.067 ⫺0.072 0.023 ⫺0.013 ⫺0.128 ⫺0.004 0.836 0.875 0.799 0.752 ⫺0.112 ⫺0.110 ⫺0.043 ⫺0.040 ⫺0.028 1.107 3.354 Notes: Total cumulative ⫽ 77.028%; OEA ⫽ others’ emotion appraisal; SEA ⫽ self-emotion appraisal; UOE ⫽ use of emotion; ROE ⫽ regulation of emotion; CAC ⫽ cognitive-appraisal coping; PSC ⫽ problem-solving coping; EFC ⫽ emotion-focused coping; JS ⫽ job satisfaction; italic data ⫽ factor loading values of each factors Corresponding author Hye Hyun Yoon can be contacted at: hhyun@khu.ac.kr For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com 1675 Table AI. Exploratory factor analysis Downloaded by Robert Gordon University At 03:45 20 May 2019 (PT) This article has been cited by: 1. PanWen, Wen Pan, SunLiuyuan, Liuyuan Sun, SunLi-yun, Li-yun Sun, LiChenwei, Chenwei Li, LeungAlicia S.M., Alicia S.M. Leung. 2018. Abusive supervision and job-oriented constructive deviance in the hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 30:5, 2249-2267. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF] 2. Bani-MelhemShaker, Shaker Bani-Melhem, ZeffaneRachid, Rachid Zeffane, AlbaityMohamed, Mohamed Albaity. 2018. Determinants of employees’ innovative behavior. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 30:3, 1601-1620. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF] 3. ChiaYew Ming, Yew Ming Chia, ChuMackayla J.T., Mackayla J.T. Chu. 2017. Presenteeism of hotel employees: interaction effects of empowerment and hardiness. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 29:10, 2592-2609. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF] 4. WuXue, Xue Wu, ShieAn-Jin, An-Jin Shie. 2017. The relationship between customer orientation, emotional labour and job burnout. Journal of Chinese Human Resources Management 8:2, 54-76. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]