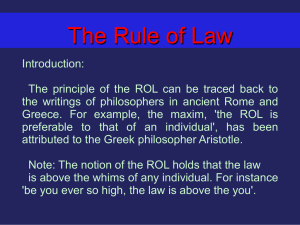

THE MODERN LAW REVIEW Volume 81 September 2018 No. 5 The Rule of Law and the Rule of Empire: A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context Dylan Lino∗ The idea of the rule of law, more ubiquitous globally today than ever before, owes a lasting debt to the work of Victorian legal theorist A. V. Dicey. But for all of Dicey’s influence, little attention has been paid to the imperial entanglements of his thought, including on the rule of law. This article seeks to bring the imperial dimensions of Dicey’s thinking about the rule of law into view. On Dicey’s account, the rule of law represented a distinctive English civilisational achievement, one that furnished a liberal justification for British imperialism. And yet Dicey was forced to acknowledge that imperial rule at times required arbitrariness and formal inequality at odds with the rule of law. At a moment when the rule of law has once more come to license all sorts of transnational interventions by globally powerful political actors, Dicey’s preoccupations and ambivalences are in many ways our own. ‘The precise issue we raise is this – that throughout our empire the British rule shall be the rule of law . . . ’1 In the speeches of developmental experts and the policy documents of international institutions, in the reports of think tanks and global indices of good governance, a four-word phrase has become more ubiquitous than ever. That phrase is, of course, ‘the rule of law’. As Martin Krygier has put it, the rule of law is ‘so totally on every aid donor’s agenda that it has become an unavoidable cliché of international organizations of every kind’.2 Spreading the rule of law is now both the means and the end for an array of international interventions of varying scale and intensity, especially in the Global South. Promoting the rule of law has, for instance, become a core objective of the World Bank in supporting development projects, the United Nations Security Council in authorising sanctions and peacekeeping missions, the International Criminal ∗ Lecturer, University of Western Australia Law School. Special thanks are due to Samuel Moyn for his help in developing the ideas in this article. Thanks also to John Allison, Duncan Bell, Donal Coffey, Ann Curthoys, Coel Kirkby, Priyasha Saksena and Oren Tamir. 1 F. Harrison, Martial Law: Six Letters to ‘The Daily News’ (London: The Jamaica Committee, 1867) 4. 2 M. Krygier, ‘The Rule of Law: Pasts, Presents, and Two Possible Futures’ (2016) 12 Annual Review of Law and Social Science 199, 200. C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License bs_bs_banner Court in prosecuting international crimes and occupying forces in seeking to restore order following military interventions.3 With increasing efforts to establish the rule of law in the Global South by powerful Western states, nongovernmental organisations and international institutions, the ideal may have become ‘our modern mission civilisatrice’.4 That ubiquitous four-word phrase has, it would seem, travelled a great distance from its more provincial inception in the constitutional theory of late-Victorian England. The idea of ‘the rule of law’ was first elaborated by the Oxford law professor Albert Venn Dicey (1835–1922), who developed a deeply influential account in his seminal Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (LOTC), first published in 1885.5 To be sure, others before Dicey had occasionally used the phrase, if only in passing, in a similar way.6 More fundamentally, in Britain, ideas about the importance of law and lawfulness had possessed a powerful hold in earlier times and on the minds of earlier thinkers: the rule of law existed as an ideal avant la lettre de Dicey.7 And contrary to what Judith Shklar caustically described as ‘Dicey’s unfortunate outburst of AngloSaxon parochialism’, political and intellectual traditions of legality had also developed in places outside England.8 But it was Dicey who first congealed ‘the legality of English habits and feelings’ into an extended constitutional account of ‘the rule of law’ and elevated it to ‘the distinguishing characteristic of English 3 A classic statement identifying this trend is T. Carothers, ‘The Rule of Law Revival’ (1998) 77 Foreign Affairs 95. See further, for example, D. M. Trubek and A. Santos (eds), The New Law and Development: A Critical Appraisal (Cambridge: CUP, 2006); S. Humphreys, Theatre of the Rule of Law: Transnational Legal Intervention in Theory and Practice (Cambridge: CUP, 2010); J. Farrall and H. Charlesworth (eds), Strengthening the Rule of Law Through the UN Security Council (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016); J. Stromseth, D. Wippman and R. Brooks, Can Might Make Rights? Building the Rule of Law After Military Interventions (Cambridge: CUP, 2006); B. Rajagopal, ‘Invoking the Rule of Law in Post-Conflict Rebuilding: A Critical Examination’ (2008) 49 Wm & Mary L Rev 1347. 4 T. Ginsburg, ‘In Defense of Imperialism? The Rule of Law and the State-Building Project’ in J. E. Fleming (ed), Getting to the Rule of Law: NOMOS L (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2011) 224. See also R. Brooks, ‘The New Imperialism: Violence, Norms, and the “Rule of Law”’ (2003) 101 Mich L Rev 2275. 5 A. V. Dicey, Lectures Introductory to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (London: Macmillan and Co, 1885). 6 For a use of the phrase ‘the rule of law’ before Dicey used it, see the epigraph to this article. See also J. W. F. Allison, The English Historical Constitution: Continuity, Change and European Effects (Cambridge: CUP, 2007) 157 n 2. 7 cf Krygier, n 2 above, 200–201. See, for example, H. W. Arndt, ‘The Origins of Dicey’s Concept of the “Rule of Law”’ (1957) 31 ALJ 117; J. A. Sempill, ‘Ruler’s Sword, Citizen’s Shield: The Rule of Law and the Constitution of Power’ (2016) 31 J L & Pol 333; N. McArthur, ‘Laws Not Men: Hume’s Distinction Between Barbarous and Civilized Government’ (2005) 31 Hume Studies 123; E. P. Thompson, Whigs and Hunters: The Origin of the Black Act (London: Allen Lane, 1975); D. Hay, ‘Property, Authority and the Criminal Law’ in D. Hay et al (eds), Albion’s Fatal Tree: Crime and Society in Eighteenth-Century England (London: Allen Lane, 1975); B. Z. Tamanaha, On the Rule of Law: History, Politics, Theory (Cambridge: CUP, 2004) especially 25–27, chs 3–4. 8 J. Shklar, ‘Political Theory and the Rule of Law’ in A. C. Hutchinson and P. Monahan (eds), The Rule of Law: Ideal or Ideology (Toronto: Carswell, 1987) 5. See further, for example, Tamanaha, ibid, chs 1–2; M. Loughlin, Foundations of Public Law (Oxford: OUP, 2010) ch 11. Note that Shklar, Tamanaha and Loughlin still tell a Eurocentric story about the rule of law and its importance. For a non-European approach to lawfulness, see C. F. Black, The Land is the Source of the Law: A Dialogic Encounter with Indigenous Jurisprudence (London: Taylor & Francis, 2010). 740 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context institutions’.9 Alongside its commitment to the sovereignty of parliament, the English constitution was, said Dicey, defined by its instantiation of the rule of law. To Dicey, we owe not only the phrase ‘the rule of law’ but also one of the idea’s most influential expositions. Dicey’s account of the rule of law emphasised three elements: first, government through legal norms and procedures rather than unrestrained discretion; second, formal equality before the law; and third, the establishment of individual rights through gradual, bottom-up (common-law) development. These ideas continue to impact contemporary debates over the rule of law – within their conventional home of constitutional theory (especially in the common-law tradition) and beyond.10 Dicey’s account is typically understood as formalist and ‘thin’, focusing on institutional arrangements rather than normatively substantive or ‘thick’ political ideals.11 When understood in historical context, Dicey’s rule of law has also often been seen (correctly) as a defence of laissez faire individualism.12 While the Diceyan rule of law has accumulated many critics over the years, it still has its admirers.13 Loved or loathed, Dicey remains a point of departure for thinking about the rule of law today. But even as Dicey’s rule of law continues to influence contemporary debates, an important facet of his account – its entanglement with imperial rule – remains almost entirely neglected. Certainly, lawyers and historians have undertaken many invaluable studies of how the rule of law ideal has fared in practice under imperial and colonial conditions.14 Scholars have also traced the place 9 Dicey, n 5 above, 168, 171. On the originality of Dicey’s account, see J. W. F. Allison, ‘Turning the Rule of Law into an English Constitutional Idea’ in C. May and A. Winchester (eds), The Edgar Elgar Handbook on the Rule of Law (forthcoming, 2018); B. J. Hibbits, ‘The Politics of Principle: Albert Venn Dicey and the Rule of Law’ (1994) 23 Anglo-Am L R 1, 26–27. 10 In constitutional theory, see, for example, T. R. S. Allan, The Sovereignty of Law: Freedom, Constitution, and the Common Law (Oxford: OUP, 2013) especially ch 3. Outside constitutional theory, see, for example, Tamanaha, n 7 above; Humphreys, n 3 above, chs 1–2; Krygier, n 2 above. 11 P. P. Craig, ‘Formal and Substantive Conceptions of the Rule of Law: An Analytical Framework’ [1997] PL 467, 470–474; Allison, n 6 above, 158–161; cf T. R. S. Allan, Constitutional Justice: A Liberal Theory of the Rule of Law (Oxford: OUP, 2003) 18–21. 12 See, for example, Hibbits, n 9 above. 13 For admiring recent discussions and appropriations, see, for example, T. Bingham, The Rule of Law (London: Allen Lane, 2010); Allan, n 10 above; M. D. Walters, ‘Public Law and Ordinary Legal Method: Revisiting Dicey’s Approach to Droit Administratif’ (2016) 66 UTLJ 53. 14 See, for example, D. Neal, The Rule of Law in a Penal Colony: Law and Power in Early New South Wales (Cambridge: CUP, 1991); A. W. B. Simpson, ‘Round Up the Usual Suspects: The Legacy of British Colonialism and the European Convention on Human Rights’ (1996) 41 Loy L Rev 629; L. Benton, Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400– 1900 (Cambridge: CUP, 2002); N. Hussain, The Jurisprudence of Emergency: Colonialism and the Rule of Law (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2003); R. Kostal, A Jurisprudence of Power: Victorian Empire and the Rule of Law (Oxford: OUP, 2005); H. Foster, B. L. Berger and A. R. Buck (eds), The Grand Experiment: Law and Legal Culture in British Settler Societies (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008); E. Kolsky, Colonial Justice in British India: White Violence and the Rule of Law (Cambridge: CUP, 2011); J. McLaren, Dewigged, Bothered, and Bewildered: British Colonial Judges on Trial, 1800–1900 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011); S. Humphreys, ‘Laboratories of Statehood: Legal Intervention in Colonial Africa and Today’ (2012) 75 MLR 475; M. F. Massoud, Law’s Fragile State: Colonial, Authoritarian, and Humanitarian Legacies in Sudan (Cambridge: CUP, 2013). C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 741 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino of ideas of law and lawfulness within projects of imperial and colonial rule.15 However, when it comes to the man who effectively coined the phrase ‘the rule of law’, the imperial dimensions of his thought about that ideal are still to be properly explored.16 And yet, for Dicey, who was writing during the height of the ‘age of empire’, the rule of law was also bound up with the rule of empire: the British Empire in particular, at whose metropolitan centre he resided.17 Indeed, as the epigraph shows, one of the few scattered references to ‘the rule of law’ before Dicey – by Dicey’s friend and fellow lawyer-intellectual Frederic Harrison – occurred during an especially intense mid-Victorian debate over the nature of British imperial rule.18 This article seeks to bring the imperial dimensions of Dicey’s thinking about the rule of law into view. It does so as a study in intellectual history, situating Dicey’s writings within the imperial historical context in which they were composed. The article examines Dicey’s treatment of the rule of law in LOTC across its 30-year lifespan of eight editions, as well as in Dicey’s extensive other academic and journalistic works.19 Within Dicey’s thought, the rule of law and the rule of empire were in a complex and unstable relationship. In David Sugarman’s astute observation, ‘Dicey, like most people, was not internally consistent’.20 On the one hand, Dicey believed British imperialism to be justified by Britain’s possession of the rule of law – the pinnacle of civilisational achievement – and by Britain’s capacity to spread that achievement abroad. Dicey’s masterwork, the LOTC, was on this score an apology for a liberal version of the British Empire. 15 See, for example, E. Stokes, The English Utilitarians and India (Oxford: OUP, 1959) esp 55–80, ch 3, 273–310; M. Chanock, Law, Custom, and Social Order: The Colonial Experience in Malawi and Zambia (Cambridge: CUP, 1985); S. E. Merry, ‘Law and Colonialism’ (1991) 25 Law and Society Review 1889; J. Comaroff, ‘Colonialism, Culture, and the Law: A Foreword’ (2001) 26 L & Soc Inquiry 305; D. Kirkby and C. Coleborne (eds), Law, History, Colonialism: The Reach of Empire (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001); D. J. Hulsebosch, Constituting Empire: New York and the Transformation of Constitutionalism in the Atlantic World, 1664–1830 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); L. Benton and L. Ford, Rage for Order: The British Empire and the Origins of International Law, 1800–1850 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2016); K. McBride, Mr Mothercountry: The Man Who Made the Rule of Law (Oxford: OUP, 2016). 16 For important analyses putting Dicey’s rule of law in an imperial context, see T. Poole, Reason of State: Law, Prerogative and Empire (Cambridge: CUP, 2015) 197–206; D. Dyzenhaus, ‘The Puzzle of Martial Law’ (2009) 59 UTLJ 1; Kostal, n 14 above, 456–458. For a recent exploration of Dicey’s imperialism, focusing on his treatment of parliamentary sovereignty, see D. Lino, ‘Albert Venn Dicey and the Constitutional Theory of Empire’ (2016) 36 OJLS 751. 17 E. Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire 1875–1914 (New York, NY: Pantheon Books 1987). See further Lino, ibid. 18 The debate was over Governor Edward Eyre’s violent suppression of the 1865 Morant Bay uprising in Jamaica, discussed further below. Dicey and Harrison were like-minded Liberals who studied together at Oxford and moved in the same intellectual circles. See C. Harvie, The Lights of Liberalism: University Liberals and the Challenge of Democracy 1860–86 (London: Allen Lane, 1976). 19 Much of Dicey’s journalism was written anonymously. I have substantiated his authorship for materials cited using D. Haskell, The Nation: Volumes 1–105, New York, 1865–1917: Index of Titles vol 1 (New York, NY: New York Public Library 1951); Wellesley Index to Victorian Periodicals, 1824–1900 at http://wellesley.chadwyck.com (last accessed 9 January 2018). 20 D. Sugarman, ‘The Legal Boundaries of Liberty: Dicey, Liberalism and Legal Science’ (1983) 46 MLR 102, 111. 742 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context On the other hand, Dicey was forced to recognise at various points that sustaining the Empire’s hierarchical relations could necessitate oppressive departures from the rule of law – in deference to the sometimes lawless and frequently discriminatory practices of settler-colonial self-government and to the exigencies of governing rebellious colonial subjects. These departures from the rule of law in turn undercut the Empire’s very reason for existence. More fundamentally, Dicey recognised on occasion that the rule of law could itself be arbitrary and oppressive when imposed on the Empire’s ‘uncivilised’ peoples, for whom he believed it was foreign and too advanced. In Dicey’s thought on the rule of law, liberal imperialism was thus not only undermined by its own internal contradictions but also susceptible to a culturalist critique – associated with the work of Henry Maine – which emphasised the need to rule colonial subjects according to their own level of ‘civilisation’. Gaining a deeper insight into the imperial entanglements of Dicey’s thinking on the rule of law is a worthwhile undertaking. It is, in the first place, valuable for better understanding Dicey himself. For a thinker who has retained remarkable intellectual currency, bringing to light the overlooked imperial dimensions of Dicey’s ideas helps those engaging with Dicey today to gain a fuller appreciation of his thought and its potential implications. Recovering these facets of Dicey’s thought can also help in understanding the rule of law more generally and the liberalism whence it springs. Highlighting the imperial commitments and dilemmas within one of the most canonical accounts of the rule of law can reveal, to quote Krygier again, ‘concerns that have motivated the vocabularies we have inherited’ and disclose ‘intellectual dispositions, sensibilities, and traditions of thought and practice that have left significant residues in our culture’.21 Dicey’s thought demonstrates the rule of law’s potential to serve as a justification for imperial projects, at the same time as it reveals some of the difficulties in sustaining the rule of law and the rule of empire simultaneously, as well as the potential for the rule of law to collapse into its own form of arbitrary domination when imposed by one society on others. It uncovers, in other words, strong affinities but also real tensions at the conjunction of liberalism and imperialism.22 At a moment when the rule of law has once more come to license all sorts of transnational interventions by globally powerful political actors, Dicey’s preoccupations and ambivalences are in many ways our own.23 The article begins by outlining Dicey’s account of the rule of law and showing how it relied upon hierarchical nineteenth-century notions of ‘civilisation’. For Dicey and many of his contemporaries, Britain – with its supposedly unique possession of the rule of law – sat atop the civilisational hierarchy. Next, situating Dicey’s writings against Victorian controversies over British rule in India, Jamaica and Ireland, the article demonstrates how Dicey’s rule of law, especially 21 Krygier, n 2 above, 202. 22 For an excellent overview of recent work on the relationship between liberalism and imperialism, see D. Bell, Reordering the World: Essays on Liberalism and Empire (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016) ch 2. 23 For a similar but broader point, see S. E. Merry, ‘From Law and Colonialism to Law and Globalization’ (2003) 28 L & Soc Inquiry 569. C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 743 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino as articulated in LOTC, served as a liberal apology for the British Empire. The article then turns to fissures within the edifice of Dicey’s liberal imperialism: first, by focusing on moments when Dicey was forced to confront the potential incompatibilities between the rule of law and the rule of empire; and second, by showing how a culturalist critique of liberal imperialism at times undermined Dicey’s confidence in imposing the rule of law on ‘uncivilised’ peoples. THE RULE OF LAW AS CIVILISATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT Dicey was one of the leading legal scholars of late nineteenth century Britain, as well as a well-known ‘public moralist’ of a Liberal – and after 1886, a Liberal Unionist – persuasion.24 It was while serving as Vinerian Professor of English Law at Oxford from 1882 to 1909 that Dicey wrote his most influential academic works: LOTC, a treatise on private international law, and a historical study of English law and its relationship to public opinion in the nineteenth century.25 While Dicey has often and with good justification been pegged as a classic practitioner of a formalistic analytic jurisprudence, his methods were less pure and more eclectic than this, displaying repeated (and sometimes criticised) engagement with historical and comparative approaches in particular.26 As a public intellectual, Dicey reviewed books prodigiously and wrote extensively on the controversies of his day in periodicals and several books.27 Inclined towards a liberal Radicalism in his youth, Dicey, like many Victorian intellectuals, became markedly more Whiggish – even conservative – in later life, tenaciously keeping faith with laissez faire individualism in an increasingly collectivist world while exhibiting a growing scepticism of democracy in a democratising world.28 In the Liberal split over Irish Home Rule in 1886, Dicey followed the Liberal Unionists and quickly established himself as one of the most visible and forthright intellectual forces opposed to Home Rule, producing screed after screed attacking each fresh iteration of the idea.29 As the twentieth century moved into its second decade, an elderly Dicey, while maintaining an enduring commitment to liberal values, was also espousing a range 24 S. Collini, Public Moralists: Political Thought and Intellectual Life in Britain, 1850–1930 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991) 287–301. See further R. A. Cosgrove, The Rule of Law: Albert Venn Dicey, Victorian Jurist (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1982); Harvie, n 18 above. 25 Dicey, n 5 above; A. V. Dicey, A Digest of the Law of England with Reference to the Conflict of Laws (London: Stevens & Sons, 1896); A. V. Dicey, Lectures on the Relation Between Law and Public Opinion in England During the Nineteenth Century (London: Macmillan and Co, 1905). 26 M. D. Walters, ‘Dicey on Writing the Law of the Constitution’ (2012) 32 OJLS 21; J. W. F. Allison, ‘History in the Law of the Constitution’ (2007) 28 Journal of Legal History 263; Allison, n 6 above, 7–14, ch 7. For the conventional view of Dicey, see, for example, Cosgrove, n 24 above, 23–28; Sugarman, n 20 above, 104–110. 27 Collini, n 24 above, 287–301. 28 See further Cosgrove, n 24 above; Hibbits, n 9 above, 12–18; J. Roach, ‘Liberalism and the Victorian Intelligentsia’ (1957) 13 Cambridge Historical Journal 58; Harvie, n 18 above, chs 8–9. 29 H. Tulloch, ‘A.V. Dicey and the Irish Question, 1870–1922’ (1980) 15 IJ 137; Cosgrove, ibid, especially chs 6–7, 10. 744 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context of reactionary views, including the denial of women’s suffrage and extreme measures to thwart Home Rule.30 In keeping with his strident Unionism, Dicey was also, at least from the mid-1870s, a faithful imperialist, committed to maintaining the unity of the British Empire.31 This attitude reflected a wider growth in imperial sentiment during the late-Victorian era – a shift that Dicey, ever the astute observer of public opinion, himself diagnosed.32 As will be outlined in greater detail below, Dicey’s imperialism was in large degree a liberal imperialism: he saw the British Empire as a vital means of spreading English liberty, order, justice and peace around the globe.33 Dicey also embraced the British Empire as a necessary basis for British self-preservation in a world of imperial states, as well as a patriotic project of national greatness.34 Turning to Dicey’s account of the rule of law, his classic treatment in LOTC separated the idea – at heart ‘the security given under the English constitution to the rights of individuals’ – into three analytically distinct senses.35 The first was rule through law: government was to be carried out in accordance with legally established procedures and norms rather than by way of unrestrained and potentially arbitrary power.36 In its second sense, the rule of law meant that ‘every man, whatever be his rank or condition, is subject to the ordinary law of the realm and amenable to the jurisdiction of the ordinary tribunals.’37 This was a norm of formal equality before the law, especially as applied to government officials, who were not to be given special dispensations from the ordinary law of the land, such as the rules of tort and criminal law.38 Third, the rule of law consisted of individual rights established through the bottom-up, case-by-case process of common-law development, rather than by a top-down declaration in a codified constitution.39 Like his account of the British Constitution generally, Dicey’s account of the rule of law reflected a well-established ‘whig’ interpretation of British constitutional history.40 The trajectory of that history was towards ever-greater individual liberty, which in Dicey’s account was manifest in the curtailment of arbitrary executive power through its subjection to parliamentary sovereignty, the rule of law and unwritten constitutional conventions. Dicey’s rule of law, especially in its third sense as the product of slow and steady common-law 30 On women’s suffrage, see A. V. Dicey, Letters to a Friend on Votes for Women (London: John Murray, 1909). On Home Rule, see the discussion below. 31 Lino, n 16 above, 761–764. For an early expression of scepticism about the value of large imperial states like the German Confederation, see A. V. Dicey, ‘The Influence of an Historical Idea’ (1864) 11 Macmillan’s Magazine 155, 160. 32 Lino, ibid, 757–758. See further D. Bell, The Idea of Greater Britain: Empire and the Future of World Order, 1860–1900 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007). 33 See also, Lino, ibid, 762–763. 34 ibid, 763. 35 Dicey, n 5 above, 168. 36 ibid, 172. 37 ibid, 177–178. 38 ibid, 178 (discussing this as ‘the idea of legal equality’), 207 (‘equality before the law’). 39 ibid, 208. 40 W. I. Jennings, ‘In Praise of Dicey, 1885–1935’ (1935) 13 Public Administration 123, 130–133; W. I. Jennings, The Law and the Constitution (London: University of London Press, 3rd ed, 1943) 285–297; Allison, n 6 above, 165–184. C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 745 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino development, tapped into whig histories of progressive and continuous English constitutional growth.41 Unlike in France – bête noire of the ‘diffused Burkeanism’ in nineteenth-century British political thought and historiography – constitutional rights and principles in Britain were the product of gradual accumulation rather than quixotic revolutionary declaration, grounded in the political and legal life of the people rather than theoretical abstraction divorced from society.42 In England, said Dicey, the rule of law was so embedded in society that it ‘could hardly be destroyed without a thorough revolution in the institutions and manners of the nation’.43 Along with reflecting a whig interpretation of the British Constitution, Dicey’s account of a rule of law achieved through slow accretion also tied in with notions of ‘civilisation’.44 The concept of civilisation was widely used in the nineteenth century by European thinkers as a framework for understanding differences between societies.45 The idea of civilisation typically envisioned a universal process of historical development, a common trajectory along which societies progressed (if they were not stationary). As Dicey articulated it in a 1902 lecture on ancient and modern constitutionalism, a civilised society possessed a state; it had moved beyond the Darwinian ‘struggle for existence’ involved in fighting off animal and human enemies and meeting basic material needs; it had ‘acquired the arts and knowledge which contribute to the ease and comfort of life’; and its ‘leading members possess intellectual cultivation and are acquainted with art, science, and letters’.46 In its late nineteenth century uses, including by Dicey, civilisation was generally a hierarchical concept, with different societies ranked according to their level of civilisation.47 Thinkers typically made a broad distinction between civilised and uncivilised societies – generally mapping onto the distinction between European societies (and their settler-colonial offshoots) and non-European societies – as well as finer-grained rankings within those broad categories.48 41 Dicey, n 5 above, 208–215. 42 On Dicey’s ‘diffused Burkeanism’, see Collini, n 24 above, 293; and see further S. Collini, D. Winch and J. Burrow, That Noble Science of Politics: A Study in Nineteenth-Century Intellectual History (Cambridge: CUP, 1983) 20–21, ch 6; E. Jones, Edmund Burke and the Invention of Modern Conservatism, 1830–1914: An Intellectual History (Oxford: OUP, 2017). For Dicey’s manifestation of this attitude, see Dicey, ibid, especially 211–212. Dicey further elaborated on ‘historical constitutions’ such as Britain’s (extensively contrasted with France’s ‘non-historical constitution’) in his 1900 lectures on comparative constitutionalism: A. V. Dicey, The Oxford Edition of Dicey: Comparative Constitutionalism vol 2 (Oxford: OUP, J. W. F. Allison ed, 2013) 171– 191. France figures heavily in Dicey’s account of the rule of law, invariably to prove by negative contrast England’s superior possession of the rule of law: see Allison, n 6 above, 172–184. For an excellent contextualisation of Dicey’s thinking within a long tradition of common-law thought, going back to the sixteenth-century discourse of ‘ancient constitutionalism’, see Walters, n 13 above, 57–65. 43 Dicey, n 5 above, 214. 44 Lino, n 16 above, 764–765. cf Tulloch, n 29 above, 145. 45 D. Bell, ‘Empire and Imperialism’ in G. S. Jones and G. Claeys (eds), The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Political Thought (Cambridge: CUP, 2011) 867–872; P. Mandler, ‘“Race” and “Nation” in Mid-Victorian Thought’ in S. Collini, R. Whatmore and B. Young (eds), History, Religion, and Culture: British Intellectual History, 1750–1950 (Cambridge: CUP, 2000). 46 Dicey, n 42 above, 196–197. 47 Bell, n 45 above, 867. 48 ibid. 746 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context For Dicey, a society’s civilisational progress was fundamentally intertwined with its stage of legal development.49 This idea – of a connection between civilisational attainment and legal development – was longstanding and widespread in British and European political and legal thought.50 In mid-Victorian Britain, the supposed correspondence between civilisational and legal development had been most prominently traced, in historical fashion, by Henry Maine, especially in his enormously influential Ancient Law (1861).51 According to Maine, the law of a given society was an index of progress along a more or less universal continuum from uncivilised to civilised. Though Dicey was not a classical practitioner of the historical and comparative methods that Maine did so much to popularise, and indeed was at times critical of those methods, he was undoubtedly influenced by their underlying intellectual premises.52 As Dicey observed in an 1883 review of Maine’s Dissertations on Early Law and Custom, Maine had forcefully and persuasively pressed a point hitherto overlooked by historians: namely, ‘the close connection between the legal and political development of the nation’.53 Reviewing another of Maine’s books three years later, Dicey observed that ‘[s]ince Maine’s “Ancient Law” appeared, every thinker or historian of average intelligence has become conscious of the fact that a nation’s law is the record of a nation’s genius’.54 The rule of law was, according to Dicey, a distinctive accomplishment of the English people, placing them at the pinnacle of civilisation. As several historians have emphasised, Dicey played an influential intellectual role in the late nineteenth century in connecting English national character with lawfulness, especially through his account of the rule of law.55 In Dicey’s very first treatment of the rule of law – penned in an 1875 review of William Stubbs’s Constitutional History of England – he waxed lyrical over that rule of the severe but always fixed and definite law which is the real glory of English institutions, and which, in ages when arbitrary government was universally established throughout the rest of Europe, made the English constitution, with all 49 Lino, n 16 above, 764–765. 50 See, for example, B. Bowden, The Empire of Civilization: The Evolution of an Imperial Idea (Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press, 2009) ch 5. 51 H. S. Maine, Ancient Law: Its Connection with the Early History of Society, and Its Relation to Modern Ideas (London: J Murray, 1861). See further G. Feaver, From Status to Contract: A Biography of Sir Henry Maine (London: Longmans, 1969); R. Cocks, Sir Henry Maine: A Study in Victorian Jurisprudence (Cambridge: CUP, 1988); K. Mantena, Alibis of Empire: Henry Maine and the Ends of Liberal Imperialism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010). 52 See [A. V. Dicey], ‘Stubbs’s Constitutional History of England’ (1875) 20 Nation 152, 152; [A. V. Dicey], ‘Maine’s Early History of Institutions’ (1875) 20 Nation 225; [A. V. Dicey], ‘The Influence of India on English Opinion’ (1876) 22 Nation 82; [A. V. Dicey], ‘Maine’s Early Law and Custom—I’ (1883) 37 Nation 165; [A. V. Dicey], ‘Maine’s Early Law and Custom—II’ 37 Nation 187; [A. V. Dicey], ‘Maine’s Popular Government—I’ (1886) 42 Nation 263; [A. V. Dicey], ‘Maine’s Popular Government—II’ (1886) 42 Nation 281; A. V. D. [A. V. Dicey], ‘Book Review’ (1886) 2 LQR 88, 88–89; Dicey, Law and Public Opinion n 25 above, 411–412, 455–462. 53 Dicey, ‘Maine’s Early Law and Custom—I’, ibid, 165. 54 Dicey, ‘Maine’s Popular Government—I’ n 52 above, 264. 55 Collini, n 24 above, 287–301; J. Stapleton, ‘Dicey and His Legacy’ (1995) 16 History of Political Thought 234, 234–239. C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 747 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino its obvious defects, seem the most beautiful phenomenon in the history of mankind to all statesmen and theorists interested in the welfare of the human species.56 Such sentiments, which Dicey continued to espouse into later life, were of a piece with the sense of English superiority that marked the Victorian era.57 They were also commonplace in the British legal scholarship of the time.58 As Dicey went on to spell out in the first edition of LOTC, the rule of law had emerged within England before any other state, having prevailed ‘at all times since the Norman Conquest’.59 Whereas England had before the end of the sixteenth century ‘passed through that stage of development . . . when nobles, priests, and others could defy the law’, it took most other European nations two more centuries to achieve the same feat.60 Against a common belief that the rule of law was ‘a trait common to every civilised and orderly state’, Dicey insisted that it was, at least in its most developed form, ‘peculiar to England, or to those countries which, like the United States of America, have inherited English traditions’.61 This differential attainment of the rule of law was, of course, a distinction between those peoples characterised as civilised; it was a distinction even more marked between the English and ‘the fanciful caprice of the torments inflicted by Oriental despotism’.62 As Dicey remarked in an 1898 article on the legal relations between England and America, ‘the spirit of legalism’ was ‘the main point on which the AngloSaxon race has reached a stage of civilization to which other nations have hardly attained’.63 THE RULE OF LAW AS JUSTIFICATION FOR EMPIRE The unique attainment of the rule of law by the British – and their capacity to spread its blessings of order and liberty abroad – furnished, in Dicey’s view, one 56 Dicey, ‘Stubbs’s Constitutional History of England’ n 52 above, 154. Hibbits has identified a fleeting earlier reference by Dicey to ‘the rule of regular law and the abolition of torture’ in his 1860 essay on the Privy Council, subsequently published in 1887: A. V. Dicey, The Privy Council (London: Macmillan & Co, 1887) 130–131, cited in Hibbits, n 9 above, 24 n 82. 57 See, for example, P. Mandler, The English National Character: The History of an Idea from Edmund Burke to Tony Blair (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006) chs 3–4. Compare LOTC, where Dicey styled himself not as an apologist or eulogist for the Constitution but simply as its expounder: see Dicey, n 5 above, 1–4. 58 D. Sugarman, ‘“A Hatred of Disorder”: Legal Science, Liberalism and Imperialism’ in P. Fitzpatrick (ed), Dangerous Supplements: Resistance and Renewal in Jurisprudence (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991) 34, 57. 59 Dicey, n 5 above, 167. Dicey seems to have taken this idea from William Stubbs: see Dicey, ‘Stubbs’s Constitutional History of England’ n 52 above, 154; J. W. Burrow, A Liberal Descent: Victorian Historians and the English Past (Cambridge: CUP, 1981) 138–144. 60 Dicey, n 5 above, 179. See also Dicey’s new Notes in the sixth edition on French droit administratif – which he originally understood as proof of Continental lawlessness but subsequently presented as the nineteenth-century growth of that stage of lawfulness achieved in England several centuries earlier: A. V. Dicey, Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (London: Macmillan and Co, 6th ed, 1902) 485–502. 61 Dicey, n 5 above, 172. 62 ibid, 176. On the idea of Oriental despotism, see Hussain, n 14 above, 44–55. 63 A. V. Dicey, ‘England and America’ (1898) 82 Atlantic Monthly 441, 444. 748 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context of the chief justifications for the British Empire.64 Here Dicey was working within a well-established intellectual tradition that posited English lawfulness as a central normative pillar for colonial rule.65 Dicey’s imperialism was in large part a liberal imperialism (albeit a complex and ambiguous one, as later sections of this paper will demonstrate). ‘The maintenance of the British Empire’, Dicey observed in his 1905 book Lectures on the Relation Between Law and Public Opinion in England During the Nineteenth Century, ‘makes it possible, at a cost which is relatively small, compared with the whole number of British subjects, to secure peace, good order, and personal freedom throughout a large part of the world’.66 In his journalism, Dicey penned paeans to the magnificent imperial diffusion of English law and liberty throughout the globe. A common comparator was the Roman Empire. An 1875 article speculated that English law, ‘the most original creation of English genius’, would be, ‘like the law of Rome, the most permanent record both in East and West of the greatness of its creators.’67 In an 1897 article proposing, as the title put it, ‘A Common Citizenship for the English Race’ between England and the US, Dicey observed: When at some distant period thinkers sum up the results of English as they now sum up the results of Grecian or of Roman civilisation, they will, we may anticipate, hold that its main permanent effect has been the diffusion throughout the whole world of the law of England, together with those notions of freedom, of justice, and of equity to which English law gives embodiment.68 Only Rome could rival England ‘in the capacity for establishing her own law in strange lands’, a capacity revealed in India through the codification project undertaken there by British officials.69 This was a view Dicey also expressed in private, telling his American friend Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1900 that ‘I am more and more convinced that to spread English ideas of law and justice is the one vocation of the English people as it will probably be our one permanent achievement’.70 The rule of law was, it seemed, destined for successful export through British imperialism, and one of the primary rationales underlying that imperialism. Dicey’s liberal vision of empire led him at times to denounce British policies that he believed threatened the rule of law in the imperial periphery. For instance, in an 1883 article titled ‘The Prevalence of Lawlessness in England’ – penned in the same year Dicey began writing LOTC – Dicey singled out for especial critique the departure from the rule of law in India presaged by 64 65 66 67 68 See further Lino, n 16 above, 762–763. Hussain, n 14 above, 3–5. Dicey, Law and Public Opinion n 25 above, 453. [A. V. Dicey], ‘Digby on the History of English Law’ (1875) 21 Nation 373, 373. A. V. Dicey, ‘A Common Citizenship for the English Race’ (1897) 71 The Contemporary Review 457, 470. See further D. Bell, ‘Beyond the Sovereign State: Isopolitan Citizenship, Race and Anglo-American Union’ (2014) 62 Political Studies 418. 69 Dicey, n 68 above, 470. 70 Letter from A. V. Dicey to O. W. Holmes, Jr 3 April 1900 at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn3:HLS.Libr:5348002?n=42 (last accessed 9 January 2018). C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 749 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino the so-called ‘Ilbert Bill crisis’.71 The controversy centred upon legislation put forward by Courtenay Ilbert, Law Member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, which sought to subject white British subjects in India to the jurisdiction of Indian magistrates. According to Dicey, who supported the Ilbert Bill, at stake in the debate was whether our government of India shall or shall not be carried on upon the principle that a native of Bengal is as truly a British subject as a native of Middlesex, and that the aim of our English rule should be ultimately to place all subjects of the Queen in a position of legal equality. Whenever this is accomplished the rule of law will prevail throughout the whole British Empire.72 He criticised those Conservatives who believed that British rule in India ought to be based upon force, upon privilege, upon that kind of permanent inequality of classes which is absolutely opposed to the true supremacy of legality, which is but another name for systematic justice.73 Forming a backdrop to Dicey’s rule of law were mid-century rebellions within the colonies, which had raised questions of law and lawlessness to especial prominence in Victorian political consciousness.74 The 1857 Indian Rebellion and the severe British military force deployed in response were part of that story. Dicey saw these developments as seminal to modern English and European history, when England’s imperial greatness was rescued from potential ruin.75 On one occasion, he likened Lord Canning, the Indian Governor-General during the rebellion, to Abraham Lincoln – ‘[t]he one saved the unity of the British Empire, the other the unity of the United States’ – and ascribed their success and virtue to a trust in law and exercise of mercy over unrestrained violence.76 But he elsewhere acknowledged the brutality and severe force that had accompanied the British response to the revolt, thereby raising questions as to the compatibility of the rule of law with empire.77 Another event that, as Rande Kostal has shown, demonstrated the centrality of law to Victorian England was the 1865 Morant Bay rebellion and its violent crushing under martial law – ‘lawless suppression’ as Dicey called it some two decades later – by Jamaican Governor Edward Eyre.78 The actions of Eyre and 71 A. V. D. [A. V. Dicey], ‘The Prevalence of Lawlessness in England’ (1883) 37 Nation 95. See further E. Hirschmann, “White Mutiny”: The Ilbert Bill Crisis in India and the Genesis of the Indian National Congress (New Delhi: Heritage, 1980). 72 Dicey, ibid, 96. 73 ibid. 74 A. W. B. Simpson, Leading Cases in the Common Law (Oxford: OUP, 1996) 228–229. See also Kostal, n 14 above. 75 [A. V. Dicey], ‘Green’s “History of the English People” – II’ (1880) 31 Nation 188, 188; [A. V. Dicey], ‘Thirty Years of European History – I’ (1890) 51 Nation 327, 327. 76 Dicey, n 68 above, 471–472. 77 Dicey, ‘Green’s “History of the English People” – II’, n 75 above, 188; A. V. Dicey, ‘What is the State of English Opinion About Ireland?’ (1882) 34 Nation 95, 96; A. V. Dicey, ‘English Popular Opinion About Egypt’ (1882) 35 Nation 418, 419. 78 Kostal, n 14 above; A. V. Dicey, ‘Ireland and Victoria’ (1886) 49 The Contemporary Review 169, 173. 750 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context other British officials, which resulted in the killing of over 400 black Jamaicans, became an English cause célèbre, with various criminal and civil proceedings unsuccessfully attempting to hold the perpetrators accountable.79 Playing the pivotal role in seeking to bring Eyre to justice for what were seen as unlawful and unconstitutional actions was the Jamaica Committee, established and led by a mixture of evangelicals and high-profile Liberals and Radicals, among them John Stuart Mill and John Bright.80 Dicey himself, at the time a young mover in Liberal circles, paid a subscription to the Jamaica Committee in 1867 and provided legal advice to one of the controversy’s more senior protagonists.81 Dicey’s cousin and legal luminary James Fitzjames Stephen was retained by the Committee to advise on privately prosecuting Eyre and others.82 In the eventual prosecution of several of the figures, Stephen put the legal question as ‘whether law was to be paramount within the British Empire, or whether officers could set aside the law and establish a military despotism with power of life and death’.83 That none of the criminal or civil proceedings ultimately succeeded could seem, at least for their proponents, to suggest the latter. More proximate to when and where Dicey was writing LOTC was the battle by British authorities to contain civil and political unrest in Ireland. Simmering since the middle of the nineteenth century, Irish agrarian and nationalist struggles came to a head in the sustained agitation of the Land War between 1879–82.84 Gladstone’s Liberal Government responded with the Protection of Person and Property (Ireland) Act 1881 (UK), which for an 18-month period enabled executive detention without trial of anyone who the Lord Lieutenant declared to be suspected of treason or crimes undermining law and order.85 This legislation was the latest but by no means the last in a lengthy list of ‘Coercion Acts’ passed throughout the century to quell Irish unrest.86 In an extended 1882 article titled ‘How is the Law to be Enforced in Ireland?’, Dicey condemned the 1881 Coercion Act as arbitrary and despotic, no better than the public disorder it was supposed to correct.87 ‘To oppose despotism to anarchy is in reality to pit one kind of lawlessness against another’, he proclaimed.88 Dicey favoured the restoration of ordinary law, albeit accompanied by the partial abolition of jury trial – a ‘grave inroad on constitutional traditions’, Dicey admitted, but a necessary measure for overcoming the 79 See B. Semmel, Jamaican Blood and Victorian Conscience: The Governor Eyre Controversy (Boston, Mass: Houghton Mifflin, 1962); C. Hall, Civilising Subjects: Metropole and Colony in the English Imagination, 1830–1867 (Cambridge: Polity, 2002); J. Evans, Edward Eyre, Race and Colonial Governance (Dunedin: University of Otago Press, 2005) chs 7–8; Kostal, ibid. 80 Semmel, ibid, 62–65. 81 ibid, 117; Kostal, n 14 above, 456. 82 Kostal, ibid, 46, 48–53. 83 James Fitzjames Stephen, quoted in Hussain, n 14 above, 5. 84 P. Bew, Land and the National Question in Ireland 1858–82 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1978); R. F. Foster, Modern Ireland 1600–1972 (London: Allen Lane, 1988) 402–415. 85 Bew, ibid, 145–155; C. Townshend, Political Violence in Ireland: Government and Resistance Since 1848 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983) 136–137. 86 Townshend, ibid, 55–66; A. W. B. Simpson, Human Rights and the End of Empire (Oxford: OUP, 2001) 78–80. 87 A. V. Dicey, ‘How is the Law to be Enforced in Ireland?’ (1881) 30 The Fortnightly Review 537. See also A. V. Dicey, England’s Case Against Home Rule (London: John Murray, 1886) 110–121. 88 Dicey, ‘How is the Law to be Enforced in Ireland?’, ibid, 541. C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 751 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino partiality of Irish juries towards agrarian agitators.89 While jury trial would indeed be partially abolished later in 1882 by the Prevention of Crime (Ireland) Act 1882 (UK), so too would a range of other protections of individual liberty, in what was one of the most far-reaching Coercion Acts to date.90 If these and other suppressions of rebellion in the imperial periphery suggested a tenuous foothold for the rule of law in the constitutional space outside the metropole, Dicey’s original account in LOTC overwhelmingly suggested otherwise. His analysis was peppered with cases and examples from the Empire – as, for instance, when substantiating his argument that the rule of law emerged through the accretion of common-law precedent.91 To demonstrate that the rule of law as formal equality ‘had been pushed to its utmost limit’ under the British Constitution, Dicey explained that colonial governors were, like ordinary citizens, accountable for their unlawful actions.92 He cited cases from British possessions in Senegal and Spain as well as a recent Jamaican case – though not, notably, any of the Eyre proceedings.93 Military officers too, Dicey maintained, were amenable to regular legal processes from one end of the British Empire to the other, whether ‘in England or in Van Diemen’s Land’.94 The ‘Jamaica affair’ of some two decades earlier loomed large in the background of LOTC’s treatment of the rule of law.95 In discussing the subjection of military officers to the ordinary law of the land, Dicey cited in support the 1870 civil action against Governor Eyre for his conduct during the rebellion, despite the fact that the action had failed.96 The reason why the civil case against Eyre had failed was that the Jamaican legislature had passed an Act of Indemnity protecting him. But this parliamentary intervention Dicey held up as the ‘legalisation of illegality’ and so an instantiation of the rule of law.97 If the Act of Indemnity covering Eyre’s actions contrasted with the ‘moderateness’ of Acts of Indemnity passed at Westminster, it was nonetheless far from the lawlessness of martial law.98 Martial law, Dicey confidently declared, was ‘unknown to the law of England’, at least insofar as martial law meant ‘the suspension of the ordinary law and the temporary government . . . by military tribunals’.99 In examining martial law, Dicey adopted the Liberal line taken by Fitzjames Stephen in arguing the early Jamaica affair prosecutions: during times of public emergency, the common law continued at all times to govern and constrain 89 ibid, 547. 90 See further Townshend, n 85 above, 172–180. 91 Dicey, n 5 above, 208 n 2. Of the four cases cited by Dicey to make this point at the outset of his discussion, two – Campbell v Hall (1774) 1 Cowp 204, relating to Grenada, and Mostyn v Fabrigas (1774) 1 Cowp 161, relating to Minorca – were colonial. 92 Dicey, ibid, 178. 93 ibid, 178 n 1. The cases were Mostyn v Fabrigas n 91 above; Governor Wall’s Case (1802) 28 St Tr 51; Musgrave v Pulido (1879) 5 App Cas 102. 94 Dicey, n 5 above, 306–307, 178. 95 Simpson, n 74 above, 228–229; Kostal, n 14 above, 456–458; Dyzenhaus, n 16 above, 10. 96 Phillips v Eyre (1870) LR 6 QB 1, cited in Dicey, n 5 above, 178 n 3. See further Kostal, ibid, 450; P. Handford, ‘Edward John Eyre and the Conflict of Laws’ (2008) 32 MULR 822. 97 Dicey, ibid, 249. For a critical but ultimately supportive account of Dicey’s argument, see Dyzenhaus, n 16 above. 98 Dicey, ibid, 249–250. 99 ibid, 249–250, 294–295. 752 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context the actions of public officials.100 Violence meted out by agents of the Crown to suppress unrest could be lawful, even legally required, but only if it satisfied the quite stringent common-law defence of necessity.101 At a time when the status of martial law remained deeply uncertain, this was a partisan move on the side of the Jamaica Committee to which Dicey had subscribed in his younger days.102 Dicey was utterly dismissive of the alternative arguments – promulgated by Eyre’s largely Conservative defenders during the Jamaica controversy, and reflected in the jurisprudence of Continental countries like France – that martial law allowed for the law to be wholly suspended.103 To borrow a line that FH Lawson applied to LOTC overall, ‘[h]aving come down on one side of the fence, he acted as though there had never been any fence at all’.104 As to the situation in Ireland, Dicey’s brief discussions in LOTC presented only a partial exception to his portrayal of imperial peripheries firmly under the rule of law. LOTC contained a succinct account of how the ‘extraordinary powers’ conferred by the 1881 and 1882 Coercion Acts had departed from the rule of law in one of its key applications, the right to personal freedom.105 This implied critique was consistent with Dicey’s earlier writings denouncing the ‘lawlessness’ of British efforts to suppress Irish political and agrarian unrest using coercion.106 But this brief treatment of contemporary British despotism in Ireland was subsumed within Dicey’s broader, repeated affirmation of the uniquely lawgoverned character of the British Empire, and it was also offset by LOTC’s other discussions of Ireland.107 Thus, as one of his main examples of martial law’s constitutional foreignness to Britain, Dicey lauded Wolfe Tone’s Case,108 a decision of the Irish King’s Bench issued during the failed 1798 Irish rebellion.109 The decision concerned Wolfe Tone, an Irish rebel leader captured during the unrest and sentenced to death by court-martial, even though he was not a British officer. Upon a legal challenge to Tone’s detention, the Irish King’s Bench granted habeas corpus. Dicey’s account of the case, as J. W. F. Allison has noted, was highly selective and formalist: Dicey failed to acknowledge that, by the time habeas corpus was granted, Tone had cut his throat, could not be safely moved and would die a week later still in prison.110 For Dicey, Wolfe Tone’s Case demonstrated ‘the noble energy with which judges 100 ibid, 294–301. See Kostal, n 14 above, 9–10, ch 5, 456–457. 101 Dicey, ibid, 295–298. 102 On the uncertain legal status of martial law in this period, see Kostal, n 14 above, 9–10; C. Townshend, ‘Martial Law: Legal and Administrative Problems of Civil Emergency in Britain and the Empire, 1800–1940’ (1982) 25 The Historical Journal 167, 167–176. 103 Dicey, n 5 above, 294–295, 298–300. See further Poole, n 16 above, 199–202; Kostal, ibid, 228–245, 415–427, 456–458; Townshend, ibid, 167–176. 104 F. H. Lawson, ‘Dicey Revisited’ (1959) 7 Political Studies 109, 113. 105 Dicey, n 5 above, 243–244. 106 Dicey, ‘How is the Law to be Enforced in Ireland?’, n 87 above. 107 For a related point, see I. C. Fletcher, ‘“This Zeal for Lawlessness”: AV Dicey, The Law of the Constitution, and the Challenge of Popular Politics, 1885–1915’ (1997) 16 Parliamentary History 309, 318. 108 (1798) 27 St Tr 614. 109 Dicey, n 5 above, 300–301. See further Foster, n 84 above, ch 12, especially 278–282. 110 Allison, n 6 above, 160–161. C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 753 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino have maintained the rule of regular law, even at periods of revolutionary violence’: there was ‘no more splendid assertion of the supremacy of law’.111 Compared with the more arbitrary methods of British rule in contemporary Ireland discussed earlier in LOTC, the case presented a marked – and perhaps an intentionally critical – contrast. But it also reasserted Dicey’s dominant message: that the rule of law ran throughout Britain and the many lands under its sovereignty. Overall, the impression Dicey conveyed in the original LOTC was of an Empire under the constitutional sign of lawfulness. In keeping with Dicey’s own liberal vision of the Empire, his account of the rule of law can be understood as an apology for liberal imperialism. As David Sugarman has argued, the classical British law textbook tradition – of which LOTC was a shining example – also served a tutelary function: such works neatly packaged English law and its underlying liberal principles for ready export to the colonies.112 While Dicey’s account of the rule of law can be seen as an exercise in imperial justification and colonial instruction, in largely overlooking the many departures from Dicey’s own rule-of-law ideal within the British Empire, it was also an exercise in wishful thinking.113 THE RULE OF LAW VERSUS THE RULE OF EMPIRE If Dicey’s original edition of LOTC evaded the potential incompatibility between the rule of law and the rule of empire, there were moments in Dicey’s career where he was compelled to confront that tension more directly. In these moments, Dicey was faced with the reality that, to hold the Empire together, the imperial centre might have to tolerate or initiate departures from the rule of law in the periphery. For the most part, Dicey’s liberalism gave way, albeit reluctantly, to his imperialism. One major imperial challenge to Dicey’s rule of law occurred in the field of martial law. Dicey’s rigidly liberal account of martial law was profoundly tested by the jurisprudence that emerged from the Second Anglo–Boer War of 1899–1902.114 Dicey himself was an enthusiastic supporter of the war and was buoyed by the imperial sentiment it corralled among the British public and in the colonies.115 The conflict was, he celebrated in 1903, ‘as much a war for the unity of the Empire as the war against secession was a war for the unity of the United States’.116 But what was the price of that imperial unity? Would it be constitutionally permissible to purchase such unity by sacrificing the rule of law? Emphatically suggesting an affirmative answer to that question 111 Dicey, n 5 above, 300–301. 112 Sugarman, n 58 above, 56–57; Sugarman, n 20 above, 107. On Dicey’s educative purposes in writing LOTC more generally, see J. W. F. Allison, ‘Editor’s Introduction to Volume One’ in A. V. Dicey, The Oxford Edition of Dicey: The Law of the Constitution vol 1 (Oxford: OUP, J. W. F. Allison ed, 2013) xxiv–xlii. 113 M. Taggart, ‘Ruled by Law?’ (2006) 69 MLR 1006, 1025. 114 Townshend, n 102 above, 174–182; Dyzenhaus, n 16 above, 31–33; Poole, n 16 above, 202–206. 115 Cosgrove, n 24 above, 199–201. 116 A. V. Dicey, ‘To Unionists and Imperialists’ (1903) 84 The Contemporary Review 305, 311. 754 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context was the case of Ex parte Marais,117 a 1902 Privy Council decision arising from the war. The decision in Ex parte Marais delivered a serious blow to Dicey’s theory of martial law. In Ex parte Marais, the Privy Council upheld the arrest and detention of a civilian under martial-law regulations in the Cape Colony during wartime, and shielded such military actions from review by the ordinary civilian courts, even where the courts were still functioning as normal.118 The Privy Council also rebuffed the petitioner’s Diceyan attempt to test his detention against the stringent common-law standard of necessity.119 Notably, the decision was delivered by Lord Chancellor Halsbury, who as a Conservativeaffiliated barrister had defended Governor Eyre in the prosecutions arising from Eyre’s suppression of the Morant Bay rebellion.120 The Marais decision – having unsettled the harmonious vision of a lawgoverned Empire that Dicey had promulgated in earlier editions of LOTC – occasioned a defensive and strained response from Dicey in his 1902 edition. Drawing heavily on colonial legal materials which supported his own case, especially materials relating to the Morant Bay prosecutions, Dicey appended a lengthy new Note to his treatise which did its best to minimise the Marais decision’s significance.121 He did so partly by advancing the narrowest possible readings of Marais – a narrowness justified, Dicey strangely claimed, by ‘the very width of the language’ in the judgment.122 Most significantly, Dicey relegated the Marais decision to one that affected the rule of law in the colonies, rather than the rule of law in England.123 Against his proud claim that martial law was ‘unknown to the law of England’, Dicey was forced to admit in a footnote that ‘[t]his statement has no reference to the law of any other country than England, even though such country may form part of the British Empire’.124 In other words, the rule of law might just be held onto in the metropole, but if rebellious colonies were to be held onto, the rule of law in those places might have to be let go. The tension between maintaining imperial rule and the rule of law could manifest even in the most apparently loyal and ‘civilised’ parts of the British Empire: the settler colonies. There, the tension arose primarily from the wide powers of self-government conferred upon the settler colonies, powers accompanied by an increasingly strident imperial constitutional ethos of noninterference.125 If some statesmen had originally seen colonial self-government as a step towards the colonies’ eventual independence, the watchword by the 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 C [1902] AC 109. ibid. ibid, 110–111. Townshend, n 102 above, 182; Kostal, n 14 above, 305–315, 382–389. Dicey, n 60 above, 502–519. The decision was momentous enough to prompt a symposium in the 1902 Law Quarterly Review, the contributions to which (by Frederick Pollock among others) Dicey variously drew on and critiqued. ibid, 510–511. ibid, 283 n 3, 503, 511. ibid, 283 n 3. On the evolution of the settler colonies’ independence, see further J. M. Ward, Colonial Self-Government: The British Experience, 1759–1856 (London: The Macmillan Press, 1976); K. Roberts-Wray, Commonwealth and Colonial Law (London: Stevens & Sons, 1966) 247–257. C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 755 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino end of the nineteenth century was imperial unity.126 Somewhat paradoxically, the tempering of the Imperial Government’s involvement in settler-colonial governance came to be seen as the price of maintaining ultimate imperial supremacy. With an eye to the lessons of the American War of Independence, many British statesmen came to believe that if the bonds of empire were to be sustained, the Imperial Government would have to grant the settler colonies a wide latitude in governing their internal affairs, or even form an Imperial Federation.127 Though a staunch opponent of Imperial Federation, Dicey was a committed exponent of imperial unity, and lauded the laissez faire attitude manifest in imperial constitutional arrangements as conducive to the Empire.128 But for Dicey, there was nonetheless a problem with these arrangements: the settler colonies, liberated from the strict control of the Imperial Government, could not always be trusted to uphold the rule of law. One example of colonial lawlessness that Dicey railed against occurred in Victoria in 1883. The Victorian Government had refused entry to several Irishmen attempting relocation to Victoria after implicating fellow Irish nationalists in the 1882 murder of the Chief Secretary for Ireland and his undersecretary in Dublin.129 In a series of letters to The Times in which he clashed with the Agent-General of Victoria, Dicey denounced the Victorian Government’s actions as unlawful trespasses and assaults and an egregious departure from the rule of law, which ought to run throughout the Empire as a whole.130 Victoria was a constituent part of the Empire, and as such there was ‘no reason why the law should be less respected at Melbourne than in London’.131 A censorious Dicey, reminding Victoria that upholding the ordinary law of the land was one its ‘duties to the Crown, or, in other words, the whole Empire’, nevertheless pulled back from recommending a restoration of lawfulness through imperial interference.132 The reason was that this would have violated established constitutional convention and potentially undermined colonial allegiance to the Empire. As Dicey explained in an 1886 article, the system of colonial self-government, though subject to the supreme sovereignty of the Imperial Parliament, was ‘kept in tolerable working order by a series of understandings and mutual concessions’.133 The Victorian incident, Dicey observed, showed that the rule of law could be an unfortunate casualty of the wide latitude necessarily conceded to the self-governing colonies to secure their loyalty. ‘[C]olonial independence’, he concluded, ‘is hardly consistent with that enforcement throughout the Crown’s dominions of due respect for law which is 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 756 See generally Bell, n 32 above. ibid, 250–254. Lino, n 16 above, 777–778. See further, T. Corfe, The Phoenix Park Murders: Conflict, Compromise and Tragedy in Ireland, 1879–1882 (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1968). A. V. Dicey, ‘The Victorian Government and the Informers’, The Times (London), 2 October 1883, 12; A. V. Dicey, ‘The Victorian Government and the Informers’, The Times (London), 10 October 1883, 4; A. V. Dicey, ‘The Victorian Government and the Informers’, The Times (London), 18 October 1883, 4. Dicey, ‘The Victorian Government and the Informers’, 10 October 1883, ibid. Dicey, ‘The Victorian Government and the Informers’, 18 October 1883, n 130 above. Dicey, n 78 above, 172. C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context the main justification for the existence of the British empire.’134 In order to maintain the Empire, sometimes it was necessary for the metropole to acquiesce in settler-colonial violations of cherished British constitutional principle – thereby undercutting the Empire’s raison d’être. Such sacrifices of the rule of law relaxed imperial rule in order to shore up imperialism’s continuity. Colonial violations of formal legal equality, especially when it came to discrimination against non-white British subjects, represented further departures from the rule of law which too were – regrettably, thought Dicey – constitutionally shielded from imperial intervention. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had seen the establishment of a ‘global colour line’ throughout the British settler colonies and the United States: the construction of legal regimes aimed at sustaining whiteness and excluding and suppressing racial ‘others’.135 These developments came to trouble Dicey’s liberal sensibility, including when they impinged on the rights of ‘uncivilised’ or ‘native’ British subjects from India and elsewhere.136 In his Introduction to LOTC’s 1915 edition, Dicey lamented that the price of imperial unity was British toleration of racial discrimination in the settler colonies: Events suggest that it may turn out difficult, or even impossible, to establish throughout the Empire that equal citizenship of all British subjects which exists in the United Kingdom and which Englishmen in the middle of the nineteenth century hoped to see established throughout the length and breadth of the Empire.137 The ‘events’ that he had in mind included the enactment of severe restrictions on non-white (especially Asian) immigration in Australia and the Transvaal.138 That the Imperial Parliament had let these enactments stand demonstrated the extent of settler-colonial independence under constitutional customs established to guarantee the settler colonies’ loyalty.139 Again, the virtuous British standard of formal equality under the law had, lamentably, to be sacrificed for the sake of sustaining ultimate imperial supremacy in the settler colonies. But while Dicey generally tolerated colonial departures from the rule of law only grudgingly, as the price of sustaining empire, he would himself come dangerously close to advocating official lawlessness to maintain imperial supremacy in Ireland. The context was the fractious confrontation over the third Irish 134 ibid, 173. 135 M. Lake and H. Reynolds, Drawing the Global Colour Line: White Men’s Countries and the International Challenge of Racial Equality (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008). See also A. McKeown, Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and the Globalization of Borders (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2008). 136 An Observer [A. V. Dicey], ‘Democratic Assumptions – IV’ 53 (1891) Nation 46, 47; A. V. Dicey, ‘Mr Bryce on the Relations Between Whites and Blacks’ (1902) 75 Nation 26; R. F. Shinn and R. A. Cosgrove (eds), Constitutional Reflections: The Correspondence of Albert Venn Dicey and Arthur Berriedale Keith (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1996) 132–134, 161. 137 A. V. Dicey, Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (London: Macmillan and Co, 8th ed, 1915) xxxvi. 138 ibid, 115 n 2. This footnote cites back to his discussion of the same issue in the Introduction at xxxvi. See further McKeown, n 135 above, especially chs 5–7. 139 Dicey, n 137 above, 115 n 2. C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 757 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino Home Rule Bill in 1911–14.140 Through his earlier writings opposing Home Rule, Dicey had established a reputation as a strident but fair-minded Unionist, committed to upholding the British Constitution and its underlying principles.141 However, Dicey’s writings on the Constitution could be – and were – used in support of the Home Rule cause, a development which, as Hugh Tulloch has argued, pressed Dicey into adopting ‘various stratagems to remove those weapons he had initially handed over to his enemies’.142 As Home Rule became ever more likely from 1912, Dicey – the Constitution’s great expounder and defender – underwent a ‘gradual and painful shift towards extremism’.143 Initially opposed to anything more than passive resistance to Home Rule (such as withholding taxes), Dicey was by 1913 refusing to denounce armed resistance by militant Unionists in Ulster, and expressly contemplating ‘recourse to the use of arms’ once ‘all possibility of legal resistance is exhausted’.144 Initially adamant about the British army’s legal duty to enforce the law even against justified Ulster resistance, Dicey could by 1914 be counted among those leading Unionist stalwarts publicly encouraging the army to refuse the forceful imposition of Home Rule in Ulster.145 By sanctioning army disobedience, Dicey willingly endorsed the very thing he had built his reputation denouncing: official lawlessness. Recognising a clash between the rule of law and the rule of empire, Dicey betrayed his own liberal ideals by sacrificing the former for the sake of the latter. THE RULE OF LAW AS IMPERIAL DOMINATION If the practice of imperial rule could reveal incompatibilities with the rule of law, it could also reveal imperial tendencies internal to the rule of law itself. Whereas the notion of spreading the rule of law typically provided an apology for empire – the civilising mission of bringing of order, freedom and justice to ‘uncivilised’ peoples – in practice, the transplantation of the rule of law in distant lands could instead look a lot like straightforward domination. A key part of the problem was the cultural specificity – or in Victorian terms, the civilisational uniqueness – of the rule of law. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, British scholars and administrators increasingly recognised that to spread British institutions and practices of governance among non-European societies was to forcefully impose radical societal transformations which threatened the British Empire’s stability. While this ‘culturalist’ turn resulted not so much in a wholesale critique of imperial rule as a shift in imperial governing strategy, it nonetheless destabilised the prevailing liberal justifications for 140 See A. O’Day, Irish Home Rule, 1867–1921 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998) ch 9. 141 C. Harvie, ‘Ideology and Home Rule: James Bryce, AV Dicey and Ireland, 1880–1887’ (1976) 91 English Historical Review 298, 298–299, 301. 142 Tulloch, n 29 above, 137. 143 ibid, 161. 144 A. V. Dicey, A Fool’s Paradise: Being a Constitutionalist’s Criticism on the Home Rule Bill of 1912 (London: John Murray, 1913) 127; Tulloch, ibid, 161–162; Fletcher, n 107 above, 322–324. 145 Dicey conveyed his support for army subversion of Home Rule as one of the original signatories of the British Covenant. See further Tulloch, ibid, 161–162; Fletcher, ibid, 324–326. 758 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context empire.146 The impact of this culturalist critique is discernible within Dicey’s thinking about the rule of law. Roughly from the 1820s through the 1850s, the predominant imperial ideology for governing the British Empire’s non-European peoples centred on a liberal civilising mission.147 On this front, India was the focus of reformist zeal. Against an earlier approach to imperial rule that professed admiration for Indian traditions and sought to preserve them, the liberal reformers – a mix of evangelicals, free traders and utilitarians – saw Indian society as degraded and in urgent need of improvement.148 For many liberal administrators, the engine of such civilisational progress among the peoples of India was law.149 Accordingly, during this reformist era, India would increasingly be governed by legal institutions based, apparently, on the best European-derived practices and principles (though not, of course, democracy). Under the sign of utilitarian ideas, this period saw extensive reforms to the British Indian administration and judiciary, to land tenure and taxation, and to the criminal law through the Indian Penal Code.150 In part, such reforms were developed and implemented by a succession of British liberal luminaries – including James Mill, Thomas Babington Macaulay and John Stuart Mill – who held senior posts in the British Indian administration.151 However, after the 1857 Indian Rebellion, British imperial governance of non-Europeans came to take on more of a culturalist bent, focused increasingly on preserving native traditions rather than the civilising mission.152 As Karuna Mantena and Mahmood Mamdani have demonstrated, the pivotal figure inaugurating this shift in governing ideology was Henry Maine.153 Beyond his immense influence as an academic and public intellectual during the midVictorian era, Maine also served as Law Member of the Viceroy’s Council in India throughout much of the 1860s.154 Now more under the intellectual sway of Maine than Bentham, British ideologies of imperial governance began to appreciate that the legal ideas and institutions of ‘civilised’ societies, such as Britain, could not without danger be transplanted to those societies supposedly much lower in the scale of civilisation, such as India.155 According to Maine, imperial projects of liberal reform would, in all likelihood, lead not to civilisational advancement for the governed but to the too-rapid dissolution of native society and, potentially, to the dissolution 146 Mantena, n 51 above. 147 Stokes, n 15 above; T. R. Metcalf, Ideologies of the Raj (Cambridge: CUP, 1994) 28–43; ibid, ch 1. 148 Stokes, ibid, ch 1; Mantena, n 51 above, 22–39; Metcalf, ibid, ch 1, 28–43. 149 Stokes, ibid, 55–80, ch 3; Metcalf, ibid, 35–39. 150 Stokes, ibid, chs 2–3. 151 ibid; C. Hall, Macaulay & Son: Architects of Imperial Britain (New Haven, Ct: Yale University Press, 2012) ch 5; Mantena, n 51 above; L. Zastoupil, John Stuart Mill and India (Stanford. CA: Stanford University Press, 1994). 152 Mantena, ibid; M. Mamdani, Define and Rule: Native as Political Identity (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2012); Metcalf, n 147 above, 43–65. 153 Mantena, ibid; Mamdani, ibid, ch 1. 154 On Maine’s influence, see, for example, Feaver, n 51 above; A. Diamond (ed), The Victorian Achievement of Sir Henry Maine: A Centennial Reappraisal (Cambridge: CUP, 1991). On Maine’s time on the Viceroy’s Council, see further Feaver, ibid, 65–109. 155 Mantena, n 51 above. C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 759 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino of the Empire.156 Maine’s ideas counselled an approach to imperial governance that sought to conserve indigenous traditions and institutions, or at least arrest their projected decay.157 While Maine’s own record as an administrator in India did not always follow the logic of his intellectual contributions, Maine’s ideas were formative for the generation of imperial administrators that followed him – in India and beyond.158 Maine’s influence is especially evident in the latenineteenth century ascendance of ‘indirect rule’ as a strategy for governing non-European peoples throughout the British Empire.159 Dicey’s outlook on imperial rule was impacted by this shift from liberal reform to cultural accommodation, creating an ongoing tension in his thinking.160 From the mid-1870s, Dicey positively reviewed many of Maine’s writings, and took on board their lessons for the practice of imperial governance, even as he continued to espouse liberal justifications for imperial rule.161 Reviewing Maine’s 1875 Rede Lecture – an influential contribution titled ‘The Effects of the Observation of India on Modern European Thought’162 – Dicey acknowledged that Maine had made plain the difficulty of applying utilitarian principles to Indian society: It may be true that the object of government ‘ought to be the greatest happiness of the greatest number,’ but the application of this principle is difficult when the sovereign and his subjects form diametrically different estimates of the nature of happiness. . . . [A]n Englishman must find it hard to draw legitimate deductions from it when called to rule a race governed by custom rather than by habits generated by free competition, or to calculate what will be the conduct of men who think it their ‘interest’ rather to starve than to eat food which might involve a loss of caste.163 As Maine said in his lecture, he hoped that the study of Indian law would lead to a ‘wholesome distrust’ of liberal reformism among those imperial administrators ‘who, guided solely by Western social experience, are too eager for innovations which seem to them indistinguishable from improvements’.164 Maine’s hope would be partly borne out in Dicey’s thinking. While Dicey’s views on imperial rule would continue to be shaped by a culturalist sensibility throughout his life, it was a particular concern of his journalism in the early 1880s, a few years before LOTC was first published.165 156 ibid, 51–53,138–145. 157 ibid, 51–53. 158 On apparent inconsistencies between Maine’s ideas and his imperial policy-making, see Mantena, ibid, 150–151. On Maine’s influence in imperial governance, see Mantena, ibid, ch 5; Mamdani, n 152 above, chs 1–2. 159 Mantena, ibid, ch 5; Mamdani, ibid, chs 1–2; C. Kirkby, ‘Henry Maine and the Re-Constitution of the British Empire’ (2012) 75 MLR 655. 160 Lino, n 16 above, 764–767. 161 See n 52 above; Lino, ibid, 764–765. 162 H. Maine, The Effects of the Observation of India on Modern European Thought (London: John Murray, 1875). On the lecture and its influence, see Feaver, n 51 above, ch 12. 163 Dicey, ‘The Influence of India’, n 52 above, 83. 164 Maine, n 162 above, 37. 165 For a later manifestation of this attitude, see, for example, Dicey, n 42 above, 152–156. See also Lino, n 16 above, 766–767. 760 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context Towards the end of 1882, in the aftermath of Gladstone’s military intervention in Egypt, Dicey wrote about the inconsistent views of the English public on Egypt’s future: they supported Egyptian self-government while also wanting to impose ‘the standard of good administration which approves itself to English ideas of justice’.166 Like the English public, Dicey himself also seemed torn, reaching no firm conclusion as to whether Britain should extend or retrench its intervention in Egypt. But he conceded much power to the idea, itself gaining wider acceptance, ‘that even the best of European statesmen and administrators injure rather than benefit Eastern races by forcing upon them the doubtful blessings of a foreign form of civilization’.167 Writing at around the same time on the relations between England and Ireland, Dicey launched a similar culturalist critique of British rule in Ireland. One of the primary causes of Irish discontent and ‘the fruitful source of a thousand ills’ was that ‘England and Ireland have from the beginning of their ill-starred connection been countries standing at a different level, or a different stage, of civilization’.168 Dicey’s central example of this problem was the replacement of Ireland’s customary tenures with English land law during James I’s reign. To those imposing this change, it must have appeared that to pass from the irregular dominion of uncertain customs to the rule of clear, definite law, was little less than a transition from anarchy and injustice to a condition of order and equity.169 The same attitude, Dicey said, prevailed in his own day, among those who are absolutely assured that the extension of English maxims of government throughout India must be a blessing to the population of the country, and are at this moment shaping their Eastern policy upon their unwavering faith in the benefits which the European Control must of necessity confer on the Egyptian peasants.170 But according to Dicey, the unreconstructed imposition of English law on Ireland (and presumably on India and Egypt) ‘led to injustice, litigation, misery, and discontent’. The fundamental problem was that ‘[t]he rulers of the country were influenced by ideas different from those of their subjects’.171 Though Dicey was certainly no advocate for Irish independence, neither was he an uncritical apologist for the Union.172 Not entirely consistently, he could attack the British administration for its failure to uphold the rule of law when suppressing Irish discontent, while also attacking the British imposition of the rule of law for fomenting Irish discontent in the first place. It was in an 1880 article on British rule in India that Dicey most explicitly connected these concerns over civilisational difference to the rule of law. The article, a review of James Talboys Wheeler’s A Short History of India, was in fact 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 C Dicey, ‘Egypt’, n 77 above, 420. ibid, 419. [A. V. Dicey], ‘England and Ireland’ (1882) 35 Nation 267, 267. ibid. ibid. ibid, 268. Tulloch, n 29 above, 147; cf Harvie, n 141 above, 306–309. C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 761 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino one of Dicey’s earliest extended reflections on the rule of law.173 For Dicey, ‘[t]he one permanent, certain, indisputable effect of English government in the East has been the establishment of the rule of law’.174 From the rule of law’s establishment in India flowed ‘all the blessing, such as it is, and a good half (one may suspect) of the curses accruing to the natives from the might of the English crown’.175 On the one hand, British rule in India, Dicey said, had put an end to the disordered, arbitrary and at times violent government that had prevailed earlier. Invoking tales of the sadistic killing of criminals who were slated to be freed, vicious raids by Mahratha rulers to levy excessive taxes on the population and chaotic processes of succession, Dicey concluded that ‘[t]he establishment of English supremacy was the substitution of an administration like that of Rome for anarchy worse than that of the middle ages’.176 For the supposedly uncivilised peoples of India, the rule of law represented extraordinary and rapid advancement. On the other hand, this ‘sudden creation of legal order’ in India also had a ‘dark side [that] may not be as visible to Englishmen, but it will certainly be seen by future historians’.177 Explicitly drawing on Maine’s work as well as the English experience in Ireland, Dicey insisted that the rule of law could become particularly oppressive ‘where foreign tribunals deal with a society of which they do not understand either the habits or the ideas’.178 Even when trying to respect Indian customs, British administrators transformed them, thereby dangerously disrupting existing social hierarchies and the natural course of civilisational development.179 In the long run, Dicey worried that Britain’s imperial government would ‘remain in a state of permanent conflict with the national spirit of its foreign subjects’ in India. ‘[T]he very merits of its administration’ – chiefly, the rule of law – ‘are likely to add strength to a spirit of opposition which if allowed head would be fatal to the existence of the empire’.180 Dicey closed his article on India with a troubled reflection on the coercion that underlay the rule of law’s export to the subcontinent: even the attempts to do justice to India may, without supposing any unnatural perversity on the part of the natives of the country, yet inflict real suffering, or, what is very much the same thing, the feeling of injury on the mass of the population. The rule of law should be the rule of justice; but even at its best the rule of law will not excite affection, and it will often appear to be the rule of unsympathizing force.181 173 [A. V. Dicey], ‘Wheeler’s Short History of India’ (1880) 31 Nation 240; J. Talboys Wheeler, A Short History of India and of the Frontier States of Afghanistan, Nipal, and Burma (London: Macmillan and Co, 1880). 174 Dicey, ibid, 240. 175 ibid. 176 ibid, 240–241. 177 ibid, 241. 178 ibid. 179 ibid. 180 ibid. 181 ibid. 762 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context That liberal British rule in India ultimately relied upon force was a point that had been emphatically pressed, and wholeheartedly embraced, in the authoritarian liberalism of Dicey’s cousin James Fitzjames Stephen.182 A prominent jurist and intellectual as well as Maine’s successor as Law Member on the Viceroy’s India Council, Stephen became – partly as a result of his Indian experience – one of the harshest internal critics of liberalism, especially for its blindness to the necessity of the coercive power of law to serve the greater good.183 But where Stephen unashamedly lauded force as the beneficent engine of law and order in India, Dicey scrupled. For the man who would soon become known as the great expounder and partisan of the rule of law, his frank expression of doubt about its value is an extraordinary conclusion. While Dicey did not propose an end to the enforcement of the English rule of law in India, he clearly discerned its capacity to do harm there. What Dicey’s ambivalence reveals is an unresolved tension within his account of the rule of law, the different strands of which could pull in different directions. There was, on the one hand, the unqualified virtue of rule conducted not by executive caprice but through law that was formally equal. But on the other hand, for those qualities to be truly instantiated, they had to emerge from the bottom up through gradual processes of legal development. Thus, after a steady, centuries-long civilisational progression, the rule of law had in Britain reached its apogee. But transplanted to the supposedly much less advanced India, the rule of law could be indistinguishable from foreign domination. Dicey’s conclusion was a curious mix of English superiority with sentiment at times edging towards the anti-imperial – and a moment of ambivalence for the rule of law as both justification for and practice of empire. CONCLUSION With rule-of-law talk more globally ubiquitous than ever, it is worth revisiting the thinking of the person who first made the phrase famous. In particular, it is worth examining how Dicey’s thinking on the rule of law was shaped by and responded to the imperial context in which it developed. For those who continue to invoke Dicey today, whether sympathetically or critically, seeing the imperial entanglements of Dicey’s rule of law puts it into a new and revealing light. This article has sought to show how Dicey’s rule of law emerged from a constitutional culture that was formed not simply out of the insular materials of British law, politics and history, but also out of the oftenfraught encounters with diverse peoples around the globe over whom Britain claimed and exercised sovereignty. In Dicey’s account, the rule of law was a distinguishing mark of English civilisational superiority, one that justified and underpinned the exercise of British imperial rule. And yet Dicey was forced to acknowledge that the exigencies of imperial governance required arbitrariness 182 On Stephen’s authoritarian liberalism, see Stokes, n 15 above, 273–310; Metcalf, n 147 above, 56–59; Mantena, n 51 above, 38–46. 183 See especially J. Fitzjames Stephen, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity (New York, NY: Holt & Williams, 1873). See further Roach, n 28 above, 60–67 and the references in the previous footnote. C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 763 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License Dylan Lino and formal inequality at odds with the rule of law and the liberal Empire it was supposed to uphold. The very civilisational distinctiveness that apparently made the rule of law so remarkable, and its English possessors so superior, also at times led Dicey to doubt the justice and wisdom of imposing it upon the Empire’s ‘uncivilised’ peoples. At a time when international institutions and powerful Western states are once again engaged in a global mission to spread the rule of law, the study of Dicey’s thought may also be instructive in unearthing enduring tendencies within thinking about the rule of law – and prompt reflection on the role of such thinking in supporting consequential and controversial political projects. Where in Dicey’s day the rule of law was seen as the peak of civilisational achievement – an achievement that licensed and fed into Britain’s imperial endeavours – it is difficult to escape the conclusion that in our day discourses of ‘development’ now play the role that ‘civilisation’ once did in sustaining transnational interventions for promoting the rule of law.184 Dicey’s struggles to marry his liberalism with his imperialism also demonstrate an abiding challenge: of reconciling the ideals underpinning the rule of law – justice, non-arbitrariness, equality – with the hierarchy and violence of empire. In raising hard questions about the globalisation of the rule of law, as Paul Kahn reminds us, ‘[w]e should not romanticize the possibility of alternatives – real or imagined – but neither should we assume that the answer is obvious’.185 If the rule of law is ‘a cultural achievement of universal significance’, it remains an open question whether the universal significance of that cultural achievement is attributable to its unimpeachable political attractiveness or to the potency with which certain of its exponents have been able to foist it – or at least particular versions of it – upon the rest of the world.186 184 See, for example, S. Pahuja, Decolonising International Law: Development, Economic Growth and the Politics of Universality (Cambridge: CUP, 2011) ch 5. 185 P. W. Kahn, The Cultural Study of Law: Reconstructing Legal Scholarship (Chicago. Ill: University of Chicago Press, 1999) 5. 186 Thompson, n 7 above, 265. 764 C C 2018 The Modern Law Review Limited. 2018 The Author. The Modern Law Review (2018) 81(5) MLR 739–764 14682230, 2018, 5, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2230.12363 by University Of Sydney, Wiley Online Library on [18/02/2023]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License A.V. Dicey in Imperial Context