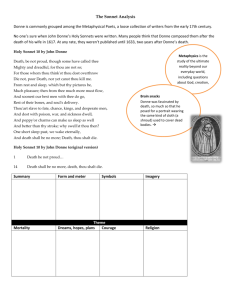

ohn Donne, Poems, Summary, Analysis, Text summary. Poems Summary Donne is firmly within the camp of metaphysical poets--those poets for whom considerations of the spiritual world were paramount compared to all earthly considerations. While a master of metaphysical expression, Donne achieves this mastery by refusing to deny the place of the physical world and its passions. He often begins with a seemingly carnal image only to turn it into an argument for the supremacy of God and the immortality of the soul. Donne's poetry falls most simply into two categories: those works composed and published prior to his entering the ministry, and those which follow his taking up the call to serve God. While many of his later poems are certainly more in the metaphysical vein that Donne has become famous for, it is nonetheless a matter of little debate that his work has a certain continuity. There is no sharp division of style or poetic ability between the two phases of Donne's literary career. Instead, it is only the emphasis of subject matter that changes. Donne is ever concerned with matters of the heart, be they between a man and a woman or between a man and his Creator. It is in his later poetry that Donne most often fuses the two into a seemingly paradoxical combination of physical and spiritual that gives light to our understanding of both. Poems Summary "Song" ("Goe, and catche a falling starre"): The reader is told to do impossible things like catch a meteor or find a "true and fair" woman after a lifetime of travels. The poet wishes he could go and see such a woman if she existed, but he knows that she would turn false by the time he got there. "The Sunne Rising": The poet asks the sun why it is shining in and disturbing him and his lover in bed. The sun should go away and do other things rather than disturb them, like wake up ants or rush late schoolboys to start their day. Lovers should be permitted to make their own time as they see fit. After all, sunbeams are nothing compared to the power of love, and everything the sun might see around the world pales in comparison to the beloved’s beauty, which encompasses it all. The bedroom is the whole world. "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning": The beloved should not openly mourn being separated from the poet. Their love is spiritual, like the legs of a compass that are joined together at the top even if one moves around while the other stays in the center. She should remain firm and not stray so that he can return home to find her again. “Death Be Not Proud" (Holy Sonnet 10) presents an argument against the power of death. Addressing Death as a person, the speaker warns Death against pride in his power. Such power is merely an illusion, and the end Death thinks it brings to men and women is in fact a rest from world-weariness for its alleged “victims.” The poet criticizes Death as a slave to other forces: fate, chance, kings, and desperate men. Death is not in control, for a variety of other powers exercise their volition in taking lives. Even in the rest it brings, Death is inferior to drugs. Finally, the speaker predicts the end of Death itself, stating “Death, thou shalt die.” Analysis " Thou hast made me, and shall thy work decay? As a child, John Donne was persecuted for being a Catholic in a country that was predominately Protestant. He was distantly related to Sir Thomas More, who was a "great Catholic humanist and martyr" (1260). Donne's religious affiliation prevented him from having any sort of public career, and he was not even allowed to get a degree from a university. Donne decided to go abroad, during which time he studied theology. When Donne returned to London sometime in the 1590s, he converted to the English church. King James wanted Donne to take an ecclesiastical career, and in 1615 Donne was ordained in the Church of England. Donne's sermons were just as clever and bold as his previous poems, which allowed him to establish a very distinguished career for himself. Donne's poems began to reflect his increasingly "anxious contemplation of his own mortality" (1261). In Donne's Holy Sonnets #1, he is speaking directly to God, asking God to hurry up and fix him before the devil takes hold of his soul. The rhyme scheme of this poem is ABBA CDDC EFEF GG, which is the English sonnet. It consists of three quatrains and one rhyming couplet at the end. Thou hast made me, and shall thy work decay? Repair me now, for now mine end doth haste; I run to death, and death meets me as fast, And all my pleasures are like yesterday. (lines 1-4) The narrator is asking God if He is just going to let His work go to waste. He demands that God fix him quickly, because death is upon him. He is scared that God will not absolve his sins before he dies, and he will then not be able to enter into heaven. In line four, he is describing the moment where your life flashes before your eyes when you are sure that you are going to die. I dare not move my dim eyes any way, Despair behind, and death before doth cast Such terror, and my feeble flesh doth waste By sin in it, which it towards hell doth weigh. (5-8) He does not want to move his eyes away from God, because he is scared that the devil will take that opportunity to damn him to an eternity in hell. The sins that he has amounted during the course of his life scares him just as much as his impending death; if he is found unworthy of God's love, he will have to suffer the consequences. His sins are rotting away his flesh, and they are so heavy that he believes he is slowing sinking into hell. Only thou art above, and when towards thee By thy leave I can look, I rise again; But our old subtle foe so tempteth me That not one hour myself I can sustain. (9-12) God is the only one who matters now; his last judgment will decide whether the narrator has done enough to get into heaven. It is by God's grace that he will rise up into heaven; so he will look up to heaven in hopes that he will soon be going there. The devil is still there trying to tempt the narrator, and if God doesn't take him soon then his soul will be going with the devil. Thy grace may wing me to prevent his art, And thou like adamant draw mine iron heart. (13-14) These last two lines are the sonnets rhyming couplet, which serve to sum up the entire poem. He tells God that His grace will give him the wings to escape the clutches of the devil. The last line is an analogy: God is like a giant magnet that attracts the narrator's iron heart. I am a little world made cunningly. Here, I will present two alternate readings of this sonnet, being an allegorical interpretation of the judgement that will one day meet us all, and the other being a more common theme for the sonnet, that of love, in this case love that has failed. Firstly, the sonnet's speaker describes himself as "a little world made cunningly / Of elements, and an angelic sprite;" in other words, he is comprised both of his actual, physical parts, and of his soul (Donne 1-2). The speaker proclaims that "black sin hath betrayed... / [His] world's both parts," and as a result, "both parts must die" (Donne 3-4). Deeper than the surface implication of simple death, however, this implies that not only will he lose his life, but his soul will also die, or in other words, be doomed to eternal damnation as a result of his sins. The speaker pleads that "new seas" be poured "in [his] eyes, / that so [he] might / Drown [his] world with [his] weeping earnestly, / Or wash it if it must be drowned no more" (Donne 7-9). This is a representation of repentence, although in this case, it seems to be a little too late. The speaker weeps over his own fate, and begs for the chance to "drown" or "clean" his soul of the sins he has committed. Indeed, the word "clean" parallels with the common religoius theme of absolution, washing ones slate clean of sins in order to attain entrance into heaven. Finally, the speaker proclaims that "the fire / of lust and envy have burnt it heretofore," so "let their flames retire, / And burn me, O Lord, with a fiery zeal" (Donne 11, 13). Lust and envy are two of the seven deadly sins, and according to many religions, dying with these on your soul will result in damnation. The references to "fire" and "burning" also correlate with the image of hell as a hot, fiery pit. In other words, the sonnet refers to the judgement that awaits everyone. If it's too late to repent, there is no way to save oneself from an eternity in the fires of hell. Alternatively, sonnets traditionally speak of love, often love for one specific, absent woman. Going back to the speaker's description of his body being comprised of both its physical self and a soul, the soul is often associated with love. "[His] world's both parts" have been "betrayed" by "black sin;" in other words, his soul has been betrayed by the woman that he loves, so that "both parts" of him "must die" (Donne 4, 3). What sort of "black sin" has been commited, then, that has so harmed his soul and its love for this woman? The speaker addresses someone in the sonnet, calling this person "You which beyond that heaven which was most high Have found new spheres, and of new lands can write" (Donne 5). He addresses this person with extollation, referring to him or her as higher than even heaven; surely only one who he loves could be referred to with such adulation. Assuming that he is referring to the woman he loves, he goes onto say that she "[Has] found new spheres, and of new lands can write" (Donne 6). In other words, she has moved onto something or someone new, implying that perhaps she has committed adultery, or simply left the speaker in favour of a new love. The speaker wants to "Drown [his] world with [his] weeping earnestly," and this obviously describes heartache and the desire to drown out his life without his love, now that she is gone (Donne 8). His world, however, has been "burnt" by "the fire / Of lust and envy;" in other words, he is destroyed by both his lust for the woman who no longer wants to be with him and the lust she now has for another man, as well as the envy that he feels for this other man who has taken his love from him (Donne 11). Therefore, he begs the "Lord" to "burn [him]... with a fiery zeal ... / which doth in eating heal" (Donne 13-14). In other words, only the fires of the Lord have the power to overcome to lust and envy that have consumed the speaker's life as a result of losing the woman he loves. If Poisonous Minerals, and If That Tree The argument that the speaker offers in the first eight lines of the poem is rejected, not because it is unreasonable, but precisely because it is reasonable. And the protests, although emotional, are "not illogical"; for even though the complaint of God preferring retribution over mercy is "a specious argument, as [the speaker] recognises in his outcry," it is an argument that has no "textual warrant” Rather the outcry of the speaker is not a recognition that the argument is specious but a recognition that the speaker "should not advance any argument against God" The ambiguity stems primarily from the reference of the pronoun "them" in "That Thou remember them, some claimer as debt,/I think it mercy, if Thou wilt forget." "Them" in this sonnet of penitence probably refers to "some," who ask to be remembered for their works, whereas the speaker pleads for salvation through God's mercy. The speaker asks that his “sinnes black memory” be erased; it is not only the speaker’s memory of his sins that is involved here, but God’s memory of them as well. The speaker’s forgetting, we can infer, is dependant upon God’s prior act of mercy in the forgiveness and forgetting of these sins. The speaker also recognises the “claim” that God should be mindful of his sins – The speaker’s own sins – just as He is mindful of the sinful state of fallen man, of original sin. The sonnet as a whole moves from prideful disputation, in which reason attempts to exempt itself and man from the special position it places him in, to a humility which recognizes both the rational claim that man’s culpability should not be forgotten, and the supra-rational process through which Christ’s sacrifice and the speaker’s contrition can cancel out that debt. The “some" in line 13 is not specific, but refers generally to all who maintain this theological position. The sonnet concludes, however, with a plea for mercy greater than justice, greater than fallen man could ever “claim as debt”: it concludes with the reiterated plea that God should forget the speaker’s sins. The unrepentant reader is initially lead to believe that it is entirely reasonable until the argument of the octet is questioned by the speaker in the lines that follow it; and the reader, now aware of his or her own sinfuhiess (as exemplified in the reading of the poem), is brought to repentance in the same way as the speaker. The basis for the rhetorical strategy that Donne uses here, I believe, can be found in Paul's epistle to the Romans One might object by saying that the substitution of the first-person pronoun "I" for the secondperson pronoun "thou" of Romans in the sonnet means that Donne is not drawing on the ancient rhetorical technique of speech-in-character found in Paul's epistle, and therefore the reader is not concerned with the outcome of the speaker's argument. The reverse, however, is true. It follows that by choosing the first person over the second-person pronoun, Donne intensifies rather than weakens the reader's participation in the speaker's fortunes and is more effective in helping the reader identify, on an emotional level, with the speaker and his attitude.. John Donne's prose and poetry are filled with references to, as well as accounts of, his selfunderstanding as a melancholic. If we take his self-professed depressive tendencies as seriously as his devotional meditations, we find that the two are interlinked: Donne often describes ecstatic religious experience with the same metaphors of earthly instability and material metamorphoses he uses to catalogue his melancholic, self-destructive inclinations. If poisonous minerals, and if that tree,Whose fruit threw death on (else immortal) us,If lecherous goats, if serpents envious Cannot be damn'd, alas ! why should I be ?Why should intent or reason, born in me,Make sins, else equal, in me more heinous ?And, mercy being easy, and glorious To God, in His stern wrath why threatens He ?But who am I, that dare dispute with Thee ?O God, O ! of Thine only worthy blood,And my tears, make a heavenly Lethean flood,And drown in it my sin's black memory.That Thou remember them, some claim as debt ;I think it mercy if Thou wilt forget. These lines include an allusion to the Garden of Eden. In Eden, first Eve and then Adam ate of the fruit God had forbidden them. As a result, God decreed that Adam and Eve should know death. In Genesis, 3:19, God says to Adam: "In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground; for out of it wast thou taken: for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return. "The Sunne Rising": “The Sunne Rising” is a 30-line poem in three stanzas, written with the poet/lover as the speaker. The meter is irregular, ranging from two to six stresses per line in no fixed pattern. The longest lines are generally at the end of the three stanzas, but Donne’s focus here is not on perfect regularity. The rhyme, however, never varies, each stanza running abbacdcdee. The poet’s tone is mocking and railing as it addresses the sun, covering an undercurrent of desperate, perhaps even obsessive love and grandiose ideas of what his lover is. The poet personifies the sun as a “busy old fool” (line 1). He asks why it is shining in and disturbing “us” (4), who appear to be two lovers in bed. The sun is peeking through the curtains of the window of their bedroom, signaling the morning and the end of their time together. The speaker is annoyed, wishing that the day has not yet come (compare Juliet’s assurances that it is certainly not the morning, in Romeo and Juliet III.v). The poet then suggests that the sun go off and do other things rather than disturb them, such as going to tell the court huntsman that it is a day for the king to hunt, or to wake up ants, or to rush late schoolboys and apprentices to their duties. The poet wants to know why it is that “to thy motions lovers’ seasons run” (4). He imagines a world, or desires one, where the embraces of lovers are not relegated only to the night, but that lovers can make their own time as they see fit. In the second stanza the poet continues to mock the sun, saying that its “beams so reverend and strong” are nothing compared to the power and glory of their love. He boasts that he “could eclipse and cloud them [the sunbeams] with a wink.” In a way this is true; he can cut out the sun from his view by closing his eyes. Yet, the lover doesn’t want to “lose her sight so long” as a wink would take. The poet is emphasizing that the sun has no real power over what he and his lover do, while he is the one who chooses to allow the sun in because by it he can see his lover’s beauty. The lover then moves on to loftier claims. “If her eyes have not blinded thine” (13) implies that his beloved’s eyes are more brilliant than sunlight. This was a standard Renaissance love-poem convention (compare Shakespeare “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun” in Sonnet 130) to proclaim his beloved’s loveliness. Indeed, the sun should “tell me/Whether both th’Indias of spice and mine/Be where thou lef’st them, or lie here with me.” Here, Donne lists wondrous and exotic places (the Indias are the West and East Indies, well known in Donne’s time for their spices and precious metals) and says that his mistress is all of those things: “All here in one bed lay” (20). “She’s all states, and all princes I”(21). That is, all the beautiful and sovereign things in the world, which the sun meets as it travels the world each day, are combined in his mistress. This is a monstrous, bold comparison, a hyperbole of the highest order. As usual, such an extreme comparison leads us to see a spiritual metaphor in the poem. As strong as the sun’s light is, it pales in comparison to the spiritual light that shines from the divine and which brings man to love the divine. The strange process of reducing the entire world to the bed of the lovers reaches its zenith in the last stanza: “In that the world’s contracted thus” (26). Indeed, the sun need not leave the room; by shining on them “thou art everywhere” (29). The final line contains a play on the Ptolemaic astronomical idea that the Earth was the centre of the universe, with the Sun rotating around the Earth: “This bed thy centre is, these walls, thy sphere.” Here Donne again gives ultimate universal importance to the lovers, making all the physical world around them subject to them. This poem gives voice to the feeling of lovers that they are outside of time and that their emotions are the most important things in the world. There is something of the adolescent melodrama of first love here, which again suggests that Donne is exercising his intelligence and subtlety to make a different kind of point. While the love between himself and his lover may seem divine, metaphorically it can be true that divine love is more important than the things of this world. The conflation of the earth into the body of his beloved is a little more difficult to understand. Donne would not be the first man who likened his female lover to a field to be sown by him, or a country to be ruled by him. Yet, if she represents the world because God loves the world, is Donne really putting himself, as the one who loves, in the position of God? What we can say with some firmness is that the sun, which marks the passage of earthly time, is rejected as an authority. The “seasons” of lovers (with the pun on the seasons of the earth, also ruled by the sun) should not be ruled by the movements of the sun. There should be nothing above the whims and desires of lovers, as they feel, and on the spiritual level the sun is just one more creation of God; all time and physical laws are subject to God. That the sun, of course, will not heed a man’s insults and orders is tacitly acknowledged. It will continue on its way each day, and one cannot wink it out of existence. There is nothing that the poet can do to change the movements of the sun or the coming of the day, no matter how clever his comparisons. From his perspective, the whole world is right there with him, yet he knows that his perspective is limited. This conceit of railing against the sun and denying the reality of the world outside the bedroom closes the poem with a more heartfelt (and more believable) assertion that the “bed thy centre is.” It can be imagined that here he is speaking more to himself, realizing that the time he has with his lover is more important to him than anything else in his life in this moment, even while the spiritual meaning of the poem extends to the sun’s relatively weak power compared with the cosmic forces of the divine. "Song" ("Goe, and catche a falling starre"): The poem simply titled “Song” is often referred to by its opening line, “Goe, and catcher a falling starre” to distinguish it from other poems published as Donne’s Songs and Sonnets. This 27-line poem is deceptively light, upon first reading, as so much of Donne’s poetry appears. On the surface, it suggests attitudes about love and the relations between the sexes, but once again Donne’s poem carries a spiritual metaphor. The tone is lightly satirical, with deeper truths peeking out from underneath the poet’s assumed worldliness and cynicism. The meter for this poem is slightly unusual for Donne. It is not a typical “song” meter, even though that is its title. The title “Song” also gives a certain lightness and flippancy to the poem which is matched by the early lines about doing impossible things. The early lines prepare us for a cynical perspective that calls to mind the attitude of the jaded courtier singing to a collection of adults who are well-schooled in the vagaries of love. The meter—tetrameter punctuated by monometer iambic lines—creates excellent and interesting pauses in the middle of stanzas. It is typical of Donne to surprise his reader, but usually not with tricks of meter that are so blatant. The short lines, which introduce the final line of each stanza, add greatly to the musical quality of the poem. One might imagine a male singer accompanying himself, perhaps, with a lute, and pausing to strum “And sweare/No where” or “Yet shee/Will be” with a wry or joking look towards his audience. The short lines act like a caesura (a poetic pause or breath) for the stanzas, setting up the surprising final lines. For example, “Serves to advance an honest minde” is surprising because it reverses the frivolous tone of the earlier lines about impossible tasks. Near the end of the stanza the poet suddenly asks serious questions: what can cure the sting of envy, and how can an honest mind advance? On the surface, the three stanzas progress to a cynical assertion of the nature of womankind. The poet begins with a series of impossible orders to an unseen actor (who can be interpreted as another young man, or perhaps the poet himself), such as, “catch a falling starre,/Get with child a mandrake root” (1-2). A mandrake root was a mythical root in medieval lore, said to grow under hanged men, and also to be useful somehow with witchcraft. It would scream when pulled up. But then the poet becomes more serious and says, “Tell me, where all past yeares are” (3), suggesting sadness in the mention of the loss of past years. Like meteors, moments of one’s life whiz by and are lost forever, although the most weighty meteors will leave remnants on earth. That this solemnity creeps into the poem at this early point is a foreshadowing of the conclusion in the third stanza. While hearing “mermaids singing” may not be a universal human desire, the next line’s desire to keep away “envy’s stinging” (6) is one almost everyone has shared. These strange juxtapositions of fantastic desires and real human longings are jarring, which leads into the desire to find out how to separate fantasy from reality, that is, how to “advance an honest mind” (9). Yet, as part of the same list, is this goal just another impossibility? Also part of the list is finding a woman who is “both true and faire.” Is a beautiful and faithful woman possible to find, even if one travels for 10,000 days and, significantly, nights? The poet would go to her; “Such a pilgrimage were sweet” (20), but the poet cannot believe that such a woman exists. The poet goes so far to say, in the wry ending of the last stanza, that even if the traveler were to find such a one, and she were as close by as next door, that by the time the traveler’s letter was written to Donne telling him of her beauty and loyalty, she would have become unfaithful to two or even three men. The fantastical constructions in the beginning of the poem accentuate the mythical quality of this most longed-for character, the beautiful and faithful woman. This hyperbole leads us, as usual, to see Donne’s spiritual point. This poem is not just about misogyny or even a sincere statement about the alleged infidelity of women. Yes, on the surface the poem could read as a way for a young, scorned lover to cope with a woman who was false to him. And misogyny in love poems, read with a contemporary lens, might even seem like a convention in seventeenth-century poetry. Yet, a spiritual reading suggests a gender-neutral criticism of fallen humanity. As much as people may pledge themselves to be true to the divine, they fall short and might sin two or three times in the course of an afternoon. People are false the world over. "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning" The first two of the nine abab stanzas of “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” make up a single sentence, developing the simile of the passing of a virtuous man as compared to the love between the poet and his beloved. It is thought that Donne was in fact leaving for a long journey and wished to console and encourage his beloved wife by identifying the true strength of their bond. The point is that they are spiritually bound together regardless of the earthly distance between them. He begins by stating that the virtuous man leaves life behind so delicately that even his friends cannot clearly tell the difference. Likewise, Donne forbids his wife from openly mourning the separation. For one thing, it is no real separation, like the difference between a breath and the absence of a breath. For another thing, mourning openly would be a profanation of their love, as the spiritual mystery of a sacrament can be diminished by revealing the details to “the laity” (line 8). Their love is sacred, so the depth of meaning in his wife’s tears would not be understood by those outside their marriage bond, who do not love so deeply. When Donne departs, observers should see no sign from Donne’s wife to suggest whether Donne is near or far because she will be so steadfast in her love for him and will go about her business all the same. The third stanza suggests that the separation is like the innocent movement of the heavenly spheres, many of which revolve around the center. These huge movements, as the planets come nearer to and go farther from one another, are innocent and do not portend evil. How much less, then, would Donne’s absence portend. All of this is unlike the worldly fear that people have after an earthquake, trying to determine what the motions and cleavages mean. In the fourth and fifth stanzas, Donne also compares their love to that of “sublunary” (earthbound) lovers and finds the latter wanting. The love of others originates from physical proximity, where they can see each other’s attractiveness. When distance intervenes, their love wanes, but this is not so for Donne and his beloved, whose spiritual love, assured in each one’s “mind,” cannot be reduced by physical distance like the love of those who focus on “lips, and hands.” The use of “refined” in the fifth stanza gives Donne a chance to use a metaphor involving gold, a precious metal that is refined through fire. In the sixth stanza, the separation is portrayed as actually a bonus because it extends the territory of their love, like gold being hammered into “aery thinness” without breaking (line 24). It thus can gild that much more territory. The final three stanzas use an extended metaphor in which Donne compares the two individuals in the marriage to the two legs of a compass: though they each have their own purpose, they are inextricably linked at the joint or pivot at the top—that is, in their spiritual unity in God. Down on the paper—the earthly realm—one leg stays firm, just as Donne’s wife will remain steadfast in her love at home. Meanwhile the other leg describes a perfect circle around this unmoving center, so long as the center leg stays firmly grounded and does not stray. She will always lean in his direction, just like the center leg of the compass. So long as she does not stray, “Thy firmness makes my circle just, / And makes me end where I begun,” back at home (lines 35-36). They are a team, and so long as she is true to him, he will be able to return to exactly the point where they left off before his journey. "Death be not proud" Elizabethan/Shakespearean sonnet form in that it is made up of three quatrains and a concluding couplet. However, Donne has chosen the Italian/Petrarchan sonnet rhyme scheme of abba for the first two quatrains, grouping them into an octet typical of the Petrarchan form. He switches rhyme scheme in the third quatrain to cddc, and then the couplet rhymes ee as usual. The first quatrain focuses on the subject and audience of this poem: death. By addressing Death, Donne makes it/him into a character through personification. The poet warns death to avoid pride (line 1) and reconsider its/his position as a “Mighty and dreadful” force (line 2). He concludes the introductory argument of the first quatrain by declaring to death that those it claims to kill “Die not” (line 4), and neither can the poet himself be stricken in this way. The second quatrain, which is closely linked to the first through the abba rhyme scheme, turns the criticism of Death as less than fearful into praise for Death’s good qualities. From Death comes “Much pleasure” (line 5) since those good souls whom Death releases from earthly suffering experience “Rest of their bones” (line 6). Donne then returns to criticizing Death for thinking too highly of itself: Death is no sovereign, but a “slave to Fate, chance, kings, and desperate men” (line 9); this last demonstrates that there is no hierarchy in which Death is near the top. Although a desperate man can choose Death as an escape from earthly suffering, even the rest which Death offers can be achieved better by “poppy, or charms” (line 11), so even there Death has no superiority. The final couplet caps the argument against Death. Not only is Death the servant of other powers and essentially impotent to truly kill anyone, but also Death is itself destined to die when, as in the Christian tradition, the dead are resurrected to their eternal reward. Here Donne echoes the sentiment of the Apostle Paul in I Corinthians 15:26, where Paul writes that “the final enemy to be destroyed is death.” Donne taps into his Christian background to point out that Death has no power and one day will cease to exist. Posted by Dr Haseeb Sharif at 22:36 Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to FacebookShare to Pinterest No comments: Post a Comment