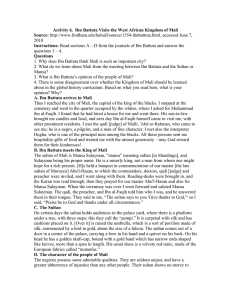

The Travels of Ibn Battuta in the Near East, Asia and Africa, 1325–1354 ( PDFDrive )

advertisement