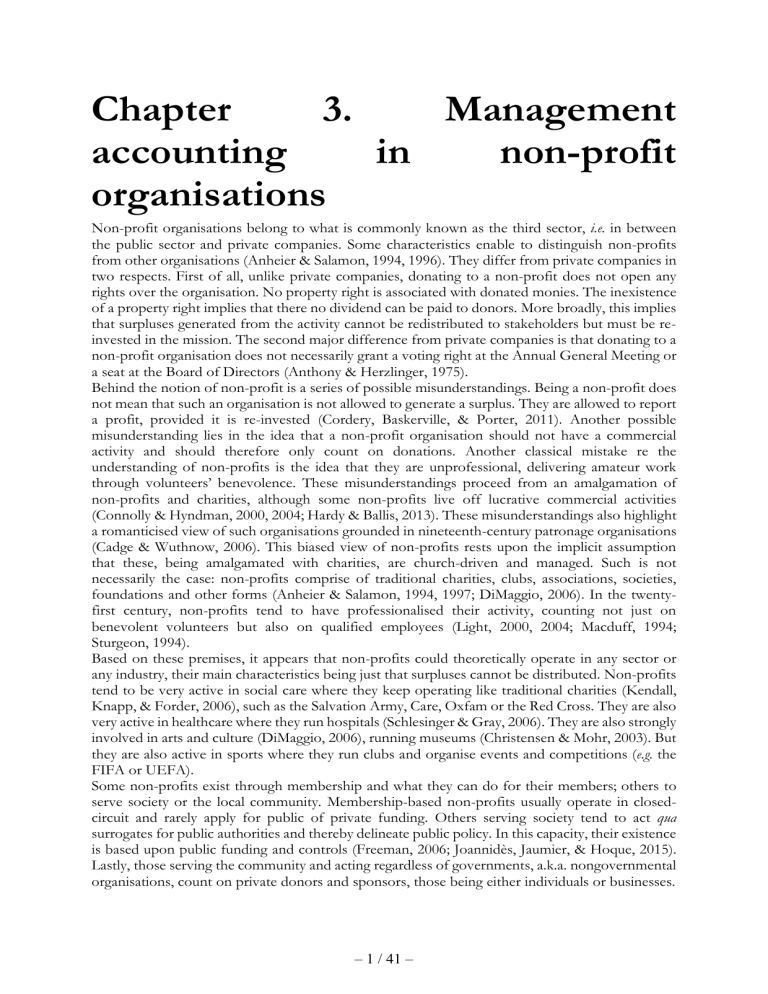

Chapter 3. Management accounting in non-profit organisations Non-profit organisations belong to what is commonly known as the third sector, i.e. in between the public sector and private companies. Some characteristics enable to distinguish non-profits from other organisations (Anheier & Salamon, 1994, 1996). They differ from private companies in two respects. First of all, unlike private companies, donating to a non-profit does not open any rights over the organisation. No property right is associated with donated monies. The inexistence of a property right implies that there no dividend can be paid to donors. More broadly, this implies that surpluses generated from the activity cannot be redistributed to stakeholders but must be reinvested in the mission. The second major difference from private companies is that donating to a non-profit organisation does not necessarily grant a voting right at the Annual General Meeting or a seat at the Board of Directors (Anthony & Herzlinger, 1975). Behind the notion of non-profit is a series of possible misunderstandings. Being a non-profit does not mean that such an organisation is not allowed to generate a surplus. They are allowed to report a profit, provided it is re-invested (Cordery, Baskerville, & Porter, 2011). Another possible misunderstanding lies in the idea that a non-profit organisation should not have a commercial activity and should therefore only count on donations. Another classical mistake re the understanding of non-profits is the idea that they are unprofessional, delivering amateur work through volunteers’ benevolence. These misunderstandings proceed from an amalgamation of non-profits and charities, although some non-profits live off lucrative commercial activities (Connolly & Hyndman, 2000, 2004; Hardy & Ballis, 2013). These misunderstandings also highlight a romanticised view of such organisations grounded in nineteenth-century patronage organisations (Cadge & Wuthnow, 2006). This biased view of non-profits rests upon the implicit assumption that these, being amalgamated with charities, are church-driven and managed. Such is not necessarily the case: non-profits comprise of traditional charities, clubs, associations, societies, foundations and other forms (Anheier & Salamon, 1994, 1997; DiMaggio, 2006). In the twentyfirst century, non-profits tend to have professionalised their activity, counting not just on benevolent volunteers but also on qualified employees (Light, 2000, 2004; Macduff, 1994; Sturgeon, 1994). Based on these premises, it appears that non-profits could theoretically operate in any sector or any industry, their main characteristics being just that surpluses cannot be distributed. Non-profits tend to be very active in social care where they keep operating like traditional charities (Kendall, Knapp, & Forder, 2006), such as the Salvation Army, Care, Oxfam or the Red Cross. They are also very active in healthcare where they run hospitals (Schlesinger & Gray, 2006). They are also strongly involved in arts and culture (DiMaggio, 2006), running museums (Christensen & Mohr, 2003). But they are also active in sports where they run clubs and organise events and competitions (e.g. the FIFA or UEFA). Some non-profits exist through membership and what they can do for their members; others to serve society or the local community. Membership-based non-profits usually operate in closedcircuit and rarely apply for public of private funding. Others serving society tend to act qua surrogates for public authorities and thereby delineate public policy. In this capacity, their existence is based upon public funding and controls (Freeman, 2006; Joannidès, Jaumier, & Hoque, 2015). Lastly, those serving the community and acting regardless of governments, a.k.a. nongovernmental organisations, count on private donors and sponsors, those being either individuals or businesses. – 1 / 41 – This chapter is structured as follows: its first section unveils the span of control in non-profits, understood as the imperative to ensure goal convergence within the organisation. The second section develops more explicitly the main areas and modes of management control in non-profits: financing, mission and operations. 1. The span of control: ensuring goal convergence Regardless of financial constraints on non-profits, their management and control are driven by two series of imperatives: an external imperative relating to regulations of their activities and an internal imperative pertaining to their identity and mission. Whatever their core activity and regardless of their relationship to public authorities, non-profits’ activities are in most countries strictly regulated. These organisations must abide by these regulations, since non-conformance to these may result in sanctions. Therefore, non-profits systematically have to prove that their procedures, processes and organisation comply. Beyond the spirit-versus-letter discussions around which compliance revolve, what matters the most is the more general idea of congruence with standards, whichever these are (Al Arabi, 2017). 1.1. Goal congruence and output control Like any other organisations, as they institutionalise, non-profits tend to become more and more bureaucratic, which is perceived as a condition of possibility for their efficiency (Anthony & Herzlinger, 1975; Ouchi, 1979, 1980; Weber, 1922). Accordingly, as hierarchy becomes stronger, controls tend to address behaviours. Conversely, when the organisation is younger and less bureaucratic, controls tend to focus more on outputs (Ouchi, 1980). Whatever form these controls take in non-profits, they emphasise the honouring of people’s commitment to the mission and its execution. It is constantly verified that members adhere to a project or the defence of the collective interest, serving a common good. Controls aim at ensuring that members work pursuant to these commonly accepted goals, be they clear or ambiguous. In non-profits, in contradistinction to private companies, this common good is hardly measurable through tangible figures, which leads management control to privilege procedures, behaviour, service quality and to a lesser extent costs (Anthony & Herzlinger, 1975). When the organisation pursues more than one goal, control revolved around their prioritisation under the purview of eventually delineating the overall mission. Therefore, the major difficulty confronting management accountants in non-profits consists of identifying and formalising goals’ prioritising. For instance, in an organisation such as the Salvation Army, serving three goals – temporary emergency aid, social inclusion and soul salvation –, goals relating to social work are subordinated to the spiritual objective, thereby contributing to its reaching (Joannidès et al., 2015). More generally, management control systems in non-profits are aimed at making all these collective and individual goals convergent, congruent and coherent Allegedly, organisational members do not spontaneously understand the appropriate behaviour for specified objectives. Accordingly, they may well not all do the same things or act in the same way, highlighting a potential risk or inconsistency throughout the organisation (de Haas & Algera, 2002). The underlying assumption is that goal convergence, by framing individual behaviours, fosters collective performance and enables higher achievements (high quality service). When it comes to control issues, non-profits are often at risk of being defiant of controls, these potentially highlighting a guardian vs. advocate divide (Lightbody, 2000, 2003) leading to the rise of opposed clans (Ouchi, 1980). Allegedly, mission advocates would emphasise the right way of conducting operations, viewing financial managers – guardian of organisational resources – as enemies to the mission. Noticeably, such misunderstanding between various occupational groups in the same organisation, coupled with a misalignment of their objectives, results in a need for controlling behaviours. It is the purpose of hierarchy and bureaucracy: appeasing opposed or separate clans within the organisation (Ouchi, 1980). Top management is required to arbitrate these – 2 / 41 – difficult relationships between various and mutually defiant occupational groups, taking two forms. Firstly, people’s behaviours are codified and regulated in order to pacify relationships and avert conflicts. Secondly, in order to encourage organisation members to do their best, collective achievements are controlled through outputs. The figure below summarises the control challenges raised by the necessary coexistence of several occupational groups (clans) and the need for making their goals converge. Figure 3.1. Clanic controls in non-profits The author reasons that the notion of congruence implies a consensus proceeding from a negotiation; albeit, the ultimate convergence of goals cannot be collapsed to goal similarity. However, difference does not systematically lead to divergence (Fiol, 1991), both terms being in no way antonyms. In return, similarity does not necessarily lead to convergence. Rather, convergence is a common direction. This latter is not necessarily the same as individual objectives but is not necessarily contradicting these. Convergence of non-profits with regulations would mean that day-to-day operations can look towards public governmental direction in a win-win relationship. It is not necessary that they share the same cognitive charts or the same mental programmes, since they are pursuing common objectives. They just go to the same what, in spite of a goal dissemblance. Reciprocally, individuals sharing the same mental programmes and the same cognitive chart can be pursuing different whats, which is not necessarily convergence. For Fiol (1991), goal convergence is an issue, precisely for individual goals are not similar, for which four modes are possible: results, behaviour, regulations, and values and beliefs, as summarised in the figure hereafter. – 3 / 41 – Figure 4.2. Clanic controls in non-profits This figure highlights the broader scope and necessity of behaviour control in a non-profit, since the main issue confronting management is that of making employees and volunteers look into the same direction and behaving consistently with one another and with organisational objectives. Therefore, common behaviours, without necessarily implying that they are standardised, appear as the cement of non-profits’ management. Assuming that members’ behaviours are homogenous or predictable, values and beliefs may appear as the second layer of convergence. These apply as the rationale for certain behaviour at the same time as they can be perceived as its external manifestation. In parallel to these personal convergence controls, procedures and norms enable that organisational members do things in the same way, so that their personal identity ultimately vanishes at the benefit of the superior mission. Procedures and norms operate as the legal cement in a non-profit enabling to give some coherence to individual actions. At the top of the pyramid are results, which are mostly a concern for management. Meeting certain results is not necessarily an objective for non-profits’ members, especially if they join because they adhere to a certain ideology or advocacy. Rather than the final outcome, what may federate them is the overall mission. As volunteers are not necessarily in a capacity of formalising and quantifying these objectives, these are a task central to managers. This ultimately is because certain objectives can be met that organisational members can see effective reasons for their membership. One could even see this pyramid as a cycle whereby effective achievements – results – foster members’ behaviours, and so on. 1.2. Convergence through results The first lever of convergence identified by Fiol (1991) lies in the attaining of objectives commonly set by the two parties involved. As both parties have different agendas, these results cannot lie expressively or explicitly in their very activities’ achievements. By-results need to be agreed upon which reflect each other’s performance on this account. Two solutions are possible, a greater and a lesser one The greater one consists of setting an objective for each party that is complementary to each other. Such is supposedly the case with socially responsible investment (Adam & Shavit, 2008; Clark & Roberts, 2010; Dillenburg, Greene, & Erekson, 2003). The lesser one consists of – 4 / 41 – setting two objectives that are attainable by each party regardless of the other but requires mutual agreement (Crettez, Deffains, & Musy, 2014; McGillis, 1978). If these non-profits are selected because they count on a unique expertise and infrastructures which public authorities do not have, it is implicitly assumed that these organisations know what they are doing, how they do so and why. Accordingly, they are not imposed operational standards but tend to be results-driven. Public authorities pay them a fee or a subsidy but leave them of their organisation and actions, provided they meet the set objectives. Such can be the case when a government commits itself to political objectives, e.g. reducing the unemployment rate to a certain level (Eldenburg & Krishnan, 2003), obtaining the organising of international events – the Olympics or the Football World Cup – (Ballou & King, 1999; Carlsson-Wall, Kraus, & Karlson, 2017). In these situations, what matters is not how things are done but the final outcome set in advance. Case n°1. The London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games Results as standards The London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (LOCOG) was established in July 2005 shortly after the Olympic bid was won by the UK Government London Olympic Bid Team. LOCOG was responsible for organising, publicising and staging the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games of 2012. Among its responsibilities were venue and competition management, sponsorship, ticket sales, the Opening and Closing Ceremonies, the Volunteer programme and monitoring and reporting project progress to the International Olympic Committee. LOCOG was also responsible for preparing and delivering all venues in Games mode, including infrastructure at temporary Games venues and, in the lead up to the Games, to host 'test' events to ensure that the venues were ready for use […] The vision which drove the Games - 'to host an inspirational, safe and inclusive Olympic and Paralympic Games and leave substantial legacy for London and the UK' - was underpinned by the four strategic objectives which were agreed by the UK Olympic Board, which were; to stage an inspirational Olympic Games and Paralympic Games for the athletes, the Olympic Family and the viewing public; to deliver the Olympic Park and all venues on time, within agreed budget and to specification, minimising the call on public funds and providing for a sustainable legacy; to maximise the economic, social, health and environmental benefits of the Games for the UK, particularly through regeneration and sustainable development in East London; and finally, to achieve a sustained improvement in UK sport before, during and after the Games, in both elite performance - particularly in Olympian and Paralympian sports - and grassroots participation. As the Organising Committee, LOCOG's specific key objective is located as the first of the Board's strategic objectives (above) 'to stage an inspirational Olympic Games and Paralympic Games for athletes, the Olympic Family and the viewing public'; this included the delivery of the following sub-objectives: 1. Deliver an inspirational environment and experience for athletes and provide a first-class experience for the Olympic Family and spectators; 2. Meet International Olympic Committee (IOC) and International Paralympic Committee (IPC) needs and specifications, including venue overlays; 3. Ensure effective and efficient planning and operation of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (including security, transport, technology, health, volunteering and accessibility); 4. Maximise audience size at venues; secure support and engagement across all sections of the UK public; 5. Deliver effective media presentation and maximise global audience size; – 5 / 41 – 6. Communicate Olympic values across the world, particularly amongst young people; 7. Stage inspiring ceremonies and cultural events; 8. Deliver an operating surplus from the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games; 9. Operate sustainable and environmentally responsible Olympic Games and Paralympic Games. Source: http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C13273031 1.3. Convergence through behaviour The second means of goal convergence lies in behaviour where conduct is codified, as with codes of ethics or codes of conduct (Avshalom & Rachman-Moore, 2004; Backhof & Martin, 1991; Brooks, 1989; Fisher, Gunz, & McCutcheon, 2001; Gaumnitz & Lere, 2002; Schwartz, 2005; Somers, 2001). This said, in order for such codes to apply and produce any effect, it is crucial that they do not remain mere incantations or procedures. As with results, the challenge, argues Fiol (1991), is to have both parties agreeing on a type of acceptable conduct. As a result, principles for conduct are issued as well as an ‘official’ interpretation thereof. As with results, consensus is required. When non-profits find themselves having their name and brand associated with a specific donor, be it a person, a business or the public sector, it must abide by certain behavioural standards set by these stakeholders. The difficulty for non-profits lies in that these behavioural standards are often implicit. Accordingly, it becomes especially important that management identifies these or formulates them in a way enabling to derive codes of conduct that volunteers and employees must stringently follow (Avshalom & Rachman-Moore, 2004; Deshpande, 1996; Martínez, 2003; Ritchie, Anthony, & Rubens, 2004). Such is often the case when the main donor is a well-established institution managing its brand and reputation. In most cases, these philanthropists do finance nonprofits for the quality of their work but foremost its consistency with the funder’s image. Accordingly, certain types of behaviours are expected or imposed on sponsored non-profits. The utmost example can be the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded by its founders delineating the behaviour they expect of their employees and volunteers for any programme managed, through codes of conduct and behavioural statements. This non-profit appears as an extension of the Gates couple’s philanthropy and is a vehicle for their name’s spreading (Aggarwal, Evans, & Nanda, 2012; Chauvey, Naro, & Seignour, 2015; Mehrpouya & Samiolo, 2016; Sansing & Yetman, 2006; Sobanjo-ter Meulen et al., 2015; Sud, VanSandt, & Baugous, 2009). Case n°2. What we expect and do not expect to hear Behavioural standards from a private sponsor A non-profit infirmary funded by a major private donor receives the following instructions as behavioural standards for staff. In case of non-conformance thither, the sponsor threatens the infirmary that it would stop financing it. What we expect to see and hear Present yourself in a professional way, in how you speak to people and your dress code. • Ensure you follow policies regarding safety, hygiene and cleanliness, conduct, information governance, use of mobiles etc. • Be aware of where you are having conversations and / or information you have access to always ensuring confidentiality is maintained at all times – 6 / 41 – • Speak up and escalate concerns appropriately, either about unsafe practice or inappropriate behaviour • Be open to challenge and welcome feedback from others • Regularly review your performance against feedback to ensure you are doing the best in your role and working within current practices. What we do not expect to see and hear Being disrespectful to people. Not following the appropriate dress code. • Inappropriate conduct or failure to follow policies and processes causes undue worry for patients and colleagues as its seen as unprofessional • Breaching confidentiality by discussing patient or staff information including leaving documentation on desks in an open environment • Criticising others for speaking up on behalf of patient safety and any inappropriate behaviour • Ignoring feedback provided and refusing to take issues on board or make changes to behaviour • Continue to work as you have done rather than reviewing performance and ensuring you are working within current practices • Bringing personal issues into the workplace and letting them interfere with your work Source: Behavioural Standards Framework –A great place to be cared for; a great place to work. p.8 Document retrieved from: https://www.uhmb.nhs.uk/files/8714/4482/8917/UHMB%20Behavioural%20Standards%2 0Framework.pdf 1.4. Convergence through procedures The third means of goal convergence, which is also the best-known, consists of setting rules and procedures that need to be followed by both parties, which raises two challenges. Firstly, the rule must be the offspring of an agreement between both parties, otherwise it cannot be enforced. Secondly, an authority independent from both parties must operate to arbitrate in case of contest. As with rule issuance, a consensus must be reached in terms of who this independent body is and what prerogatives he or she has to enforce it and compel the parties to abide by it (Armour, Deakin, Lele, & Siems, 2009; Madry, 2005; Niblett, Posner, & Shleifer, 2010). 1.4.1. Conformance and compliance The least convergence seems to occur with behaviour or rules and procedures whilst results seem to represent a middle-range form of convergence. Fiol (1991) argues that if less than three of the four modes of convergence can operate at the same time, a lesser approach than coherence and congruence must be envisaged: compliance and conformance. Yet, it is important is to understand that both are not quite fulfilling. 1.4.1.1. Conformance as the strict abiding by regulations The notion of conformance is strongly connected to systems of law or rules where a party is compelled to abide by certain principles issued by a different party. Conformance operates at two levels and raises a number of questions (Bhimani & Soonawalla, 2005; Leavitt & Maykuth, 1989; Tucker, 1962). Firstly, behind the notion of conformance is the authoritativeness of the issuing – 7 / 41 – party since there is no negotiation, contrary to coherence or congruence. One party expects to be acknowledged or recognised by the other as following its principles. Therefore, this demanding party has to make changes to its own procedures and rules of functioning to eventually arrive at new ones mirroring those whither they are expected to conform. The second level of conformance lies in the consequences of not conforming. That is, when a demanding party applies for recognition and after a certain time does not have the appropriate rules of functioning, the accrediting body can ban them or compel them to major sanctions (Cast, Stets, & Burke, 1999; Rai, 1975; Rupert, Jehn, Engen, & Reuver, 2010; Sandron & Hayford, 2002; Yair, 2007). The philosophy behind the notion of conformance is somewhat close to the subjectification mechanisms stressed in disciplinary studies (Foucault, 1975, 1984). Those who apply for recognition are not obliged to do so. Therefore, if they choose to do so, they accept all the constraints implied. They relinquish their own sovereignty and subject it to an external body that, in turn, dictates their own functioning. As the applying body finds itself in this alien regulatory system, it is now forced to do exactly as prescribed. The absence of obligation to join this new system of law results in sanctions being dissuasive in case the applying body breaches the rules to which it supposedly conforms. Where a system of conformance is very Foucauldian is in that one party transfers their own body and soul to an external regulatory body. Not just does that latter impose rules but compels behaviour and operates as a court with no possible appeal (Forneret, 2013; Frickey, 2005; Moore, 2010; Owens & Wedeking, 2011; White, 1995). Again, conformance applies because of the applying body’s willingness to subject itself. If the rule is too much of a constraint, the applying body can decide to quit, thereby belying the object of convergence. The arbitrariness underlying the notion of conformance is therefore what makes it easier to achieve, as compared to convergence of congruence. Yet, its condition of possibility lies in surrendering. Although this may happen in certain contexts and under certain conditions, research highlights an even lesser form of convergence most often in use: compliance. Contrary to conformance, compliance does not imply that sovereignty be relinquished, even though norms remain imposed by the body receiving application for recognition (Cardenas, 2011; Ee, 2011; Gilliland & Manning, 2002; Greenberg, 2010; Wright, 2011). 1.4.1.2. Compliance as a process Compliance consists of issuing standards that will be enforced by the applying body consistently with its own agenda. All possible changes in processes and rules of functioning are the applying body’s discretion (Fasterling, 2012; McKendall, DeMarr, & Jones-Rikkers, 2002; Parker, 2000; Weber & Wasieleski, 2013). This has three series of implications, one for each body and one for their relationship. Firstly, the applying body is setting their own agenda and have to prove to the accrediting body that they are so revising their internal processes as to making them converge with the receiver’s principles. That is, the applicant maintains full control over the application and convergence process at its end (Agócs, 1997; Anderson, Welsh, Ramsay, & Gahan, 2012; Armour et al., 2009; Block, 2013; Boon, Flood, & Webb, 2005). Secondly, the accrediting body is expected to issue clear minimal criteria that must be honoured by the applicant. Such criteria supposedly pertain to the core values on which the accreditor cannot make any compromise. This implies that a list of ‘to-does’ and score-sheet be set up by the accreditor. Compliance is then acknowledged when a certain score is obtained, that is when a certain amount of principles are not breached (Boyce, 2004; Christensen & Mohr, 1999; Rouse, Davis, & Friedlob, 1986). This clearly means that the accreditor loses most of the control over the applicant and the eventual honouring of its core principles. Thirdly, compliance has a major implication for the relationship between the applying and accrediting bodies. The very first implication is that accreditation eventuates ex post facto and not prior to the conduct of applicant’s operations. This means, the accreditation is often issued in response to obvious misuses or misconduct denounced by the party whose principles have been breached (Cardenas, 2011; Chartier, 2012; Fasterling, 2012; Latin, Tannehill, & White, 1976; – 8 / 41 – McKendall et al., 2002; Parker, 2000; Weber & Wasieleski, 2013). Hence, the accreditor appears as the weak in the relationship since it almost emotionally reacts to the situation, so that compliance mechanisms appear as negative regulations whose effect is that they cannot be constraining (Badiou, 2001, 2009). Compliance leads to a paradoxical situation where the norms hence issued find themselves undermining their own applicability since they are just negative, neither programmatic nor performative, and often vague (Joannidès & McKernan, 2015; McKernan, 2012; McKernan & Kosmala, 2007; McKernan & McPhail, 2012). At best, the accreditor operates qua an advisor on compliance that the applicant can consult or not (Parker, 2000). In sum, whilst coherence and congruence lead to substantial convergence conformance and compliance do make two views formally concur. The utmost form of convergence lies in congruence delineated from negotiations the accreditor and the applicant, followed by coherence. Amid the lesser forms of convergence, conformance consists of a set of rules imposed by the accreditor whilst compliance eventually appears as the imposing of the applicant’s agenda. 1.4.2. Standards and regulations for non-profits Should the abiding by standards and regulations take the form of conformance thither or compliance therewith, some of them are common to any non-profit. What may differ relates to country-specific matters, some being more inclined than others to standardising non-profits’ activity (Anheier & Salamon, 1997). Depending on the organisation’s relationship to public authorities and other private businesses, there also exist specific standards and regulations. Lastly, unions and political parties, acting as very specific non-profits, are subjected to tougher standards and controls. 1.4.2.1. Common regulations Whatever activity a non-profit organisation conducts and whatever its relationship with public authorities and private donors is, certain regulations indifferently apply to all. It is mostly regulations pertaining to health, hygiene and security, because these organisations admit the public on their premises. Technically, such regulations cover building size and structure, emergency exits, fire hydrants. Bathrooms must be organised in a certain way and cleaned following a strict schedule. The building must be accessible to people with disability, etc. Conformance is controlled by public authorities and take different forms, depending on location (country, state, region). For the same safety reasons, equipment and materials must conform to official standards. Depending on the country and the level of detail in regulations, these standards can consist in maintenance obligation and evidence thereof, an exhaustive list of allowed materials or suppliers. Such is especially the case of sports clubs, non-profit schools or hospitals where people’s safety and lives are at stake (Kennedy, Burney, Troyer, & Caleb Stroup, 2010; Samuel, Covaleski, & Dirsmith, 2009). To some extent, these standards applying to non-profits are grounded in common sense and are very similar to CSR standards applying to private companies or, more recently, human rights protection standards issued by some multinationals (Cragg, 2000; Gray & Gray, 2011; Harcourt & Harcourt, 2002; McPhail & McKernan, 2011; Whelan, Moon, & Orlitzky, 2009). Such can take the form of equal employment opportunities and non-discrimination based on class, race, gender, sexual orientation, religion or age (del Carmen Triana, Wagstaff, & Kim, 2012; Ferris & King, 1992; Roehling, 2002; Tinker & Fearfull, 2007). For instance, a Christian soup kitchen, such as the Salvation Army, is not allowed to exclude a homeless person because he or she is Muslim, and vice versa (Ng & Metz, 2015). Even though it may seem common sense that such standards should apply to non-profits, this idea is not most intuitive, insofar as non-profits may be perceived as outwith the public realm and therefore out of public control. The third type of common regulations and standards applying to most non-profits relate to skills and qualifications, i.e. professional standards. As a number of non-profits operate in industries – 9 / 41 – where private companies or the public sector are present, professional quality standards apply to them as to any other professional body. Such is especially the case for non-profits operating in education, social care, healthcare, sports and arts. That is, specific degrees, qualifications and training sessions are compulsory for staff. These regulations are aimed at ensuring service quality and professionalism regardless of the organisation’s legal status. Social workers, nurses and medical doctors, schoolteachers and sport instructors must be equally qualified wherever they work or volunteer. Case n°3. Assistant coach – Canterbury Mitre 10 Rugby Cup A job offer: Professional qualifications required The Canterbury Rugby Football Union (CRFU) has a long and proud history since it was established as the first Union in New Zealand in 1879. In 2017 Canterbury won their 9th provincial title in the last 10 seasons and are seeking to build on this success by appointing an assistant coach to join an experienced and talented team of coaches and support staff. The role is a fixed term full time poison for the Mitre 10 Cup campaign (July - October) and provides the successful applicant the opportunity to be immersed fully in one of New Zealand's leading Provincial Union performance rugby programs. Working with a passionate team you will be responsible for coaching the team, both on and off the field, to a standard of excellence that enhances the legacy of Canterbury Rugby. You will be a suitably qualified and successful coach with a proven track record and a deep understanding of the technical and tactical components of forward play and preferably the ability to coach the delivery of set piece execution (scrum, lineout and kick restarts). Just as importantly you will possess the skills, character and attitude, needed to contribute positively to the team and wider organisation's culture through living and exemplifying the CRFU standards and values. This is a unique opportunity to join a successful team within a leading organisation and contribute to its ongoing success. If you are interested in this position, please email your application to name@mail.co.nz by 4th February 2018. A full position description is available on our website at www.crfu.co.nz The Canterbury Rugby Football Union aims to build on its position as one of the leading provinces in world rugby. Its responsibilities extend from the nurturing of junior and school rugby to the management of the Mitre 10 Cup team. 1.4.2.2. Activity-specific regulations Depending on their core activity and on the type of public they are addressing, non-profit organisations are expected to either conform to or comply with regulations. That is, when these organisations only serve their members’ interest, regulations are looser than for organisations handling public policy matters and count on public monies. In this latter case, qua a surrogate for public authorities devolved a quasi-mission as a public service (see chapter for more details). Certain non-profits operating in the field of social work act on behalf of governmental authorities from which they receive funding and standards to follow (Freeman, 2006; Furneaux & Ryan, 2015). Acting qua surrogates for an elected government whose political agenda rests upon democratic promises made to voters, these non-profits are particularly subject to public accountability that is often perceived as technocratic (Dorf, 2006; Morgan, 2006; Sinclair, 1995). Such oversight tends to be particularly intense in countries characterised by a strong welfare system and in which private – 10 / 41 – benevolence is not as central, such as in France, Germany or Sweden (Esping-Andersen, 1992, 1996). Most likely due to the structure of welfare in most countries studied in research addressing accountability in non-profits (e.g., the US, the UK, Australia or New Zealand), accountability to governmental agencies has been relatively under-explored and still requires understanding. Moreover, most publications on accountability in non-profits address an existing accountability system or framework, whereas the creation of such a system is left aside. These organisations are imposed strict standards for the conduct of their operations are regularly inspected by public auditor sent from the ministry devolving them operational authority. Usually, clear books of procedures are to be applied and followed, which mostly eventuated when the concerned non-profit deals with social care or healthcare in the name or on behalf of the government. Concretely, when the Salvation Army or the Red Cross run social homes funded through public monies, house-standards do apply only if these are compatible with national standards. Case n°4. The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers Professional standards The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers are a public statement of what constitutes teacher quality. They define the work of teachers and make explicit the elements of high-quality, effective teaching in 21st century schools that will improve educational outcomes for students. The Standards do this by providing a framework which makes clear the knowledge, practice and professional engagement required across teachers’ careers. They present a common understanding and language for discourse between teachers, teacher educators, teacher organisations, professional associations and the public. Teacher standards also inform the development of professional learning goals, provide a framework by which teachers can judge the success of their learning and assist self-reflection and self-assessment. Teachers can use the Standards to recognise their current and developing capabilities, professional aspirations and achievements. Standards contribute to the professionalisation of teaching and raise the status of the profession. They could also be used as the basis for a professional accountability model, helping to ensure that teachers can demonstrate appropriate levels of professional knowledge, professional practice and professional engagement. The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers are organised into four career stages and guide the preparation, support and development of teachers. The stages reflect the continuum of a teacher’s developing professional expertise from undergraduate preparation through to being an exemplary classroom practitioner and a leader in the profession. The Graduate Standards will underpin the accreditation of initial teacher education programs. Graduates from accredited programs qualify for registration in each state and territory. The Proficient Standards will be used to underpin processes for full registration as a teacher and to support the requirements of nationally consistent teacher registration. The Standards at the career stages of Highly Accomplished and Lead will inform voluntary certification. Source: Australian Professional Standards for Teachers, February 2011, p.2 1.5. Convergence through values and beliefs The fourth lever of goal convergence proposed by Fiol (1991) consists of the sharing of common values or beliefs. Although this seems to be easy at first glance, it is likely to be the most problematic means of convergence. Values and beliefs can easily be shared when the two parties involved are similar in nature, as with professions for instance (Abernethy & Stoelwinder, 1995; Boon et al., 2005; Carlisle & Manning, 1996; Davison, 2011; Frankel, 1989). When the two parties are too – 11 / 41 – different, it becomes difficult to identify shared understandings of the world and emotions driving conduct (Schatzki, 2000, 2003, 2005). When it can appear that non-profit organisations engage in activities where values can clash with those encouraged and diffused by public authorities, controls can rest upon the abiding by official values and norms, whilst beliefs cannot be changed. Such is especially the case in countries where public schooling is on the political agenda, i.e. where schools are supposed to diffuse national values. In this case, non-profit private schools driven by other values – generally religious – than the official ones, must prove that their teaching diffuses these official values. Nowadays, with the rise of radical Islam and its spread amongst youngsters, non-profit Qur’anic schools are under public scrutiny on the grounds of the values they diffuse (Holmwood & O'Toole, 2017). The figure below summarises the formal guidance received by primary school teachers confronted with foreign pupils and cultural differences. These guidelines are aimed at ensuring goal convergence through values and beliefs Questions Evidence How do we promote the values of democracy in lessons and wider in school life? How do we value the importance of identifying and combating discrimination? Do students understand that the freedom to choose and hold other faiths and beliefs is protected in law? How do we promote tolerance between different cultural traditions by enabling students to acquire an appreciation of their own and other cultures? Do students understand the difference between executive and judiciary systems? Are pupils made aware of the difference between the law and religious law? How do we challenge opinions or behaviours that are contrary to fundamental British values? Figure 3.3. The Key for UK School governors – How does our school promote British values? https://schoolgovernors.thekeysupport.com/school-improvement-and-strategy/strategic-planning/valuesethos/promoting-british-values-in-schools/ 1.6. A note on trade unions and political parties Political parties are trade unions playing a major role in the exercise of democracy. Unions were indeed born long before political parties and appeared as the utmost form of democratic expression in private companies (Abrahamson, 1997; Ogden & Bougen, 1985). Trade Unions were first launched in reaction to the excesses in Capitalism imposed by the industrial revolution and the rise of the Communist ideal (Badiou, 2008, 2012a; Behling, 2018). Trade Unions appeared for the first time in the 1880s in the mine and steel industries in the United Kingdom and Prussia and spread throughout Europe and the United States afterwards (Behling, 2018). Almost concomitantly to the rise of trade unions, political parties were created. In the United Kingdom and in Prussia (then Germany), trade unions launched political parties to have relays in the public realm and especially in the making of law. This is how the Labour Party was born in Britain in 1880 (Thorpe, 2015) and – 12 / 41 – the German Socialist Party in 1890 – die SPD – (Hall, 2008). Even though the unionist movement has not spread uniformly across Europe, most countries have given birth to trade unions between 1890 and 1920 (Gumbrell-McCormick & Hyman, 2013). Given the centrality of trade unions and political parties in democratic life and vitality, rules imposed on them are especially though and constraining their activity. Such rules are of two orders. First of all, trade unions, to be allowed to speak on behalf and in the name of employees, must be sufficiently representative. Depending on the country, this representativeness requires full independence from political parties, as in France, Italy, Spain, Austria, Scandinavian countries or the United States. Conversely, in other countries, representativeness rests upon political affiliation, such as Germany and the United Kingdom, where they were initially established by political parties. In addition to this, depending on the country, again, trade unions must be grounded in a certain industry, as in Germany, or count on national relays, as in France and Italy. That is, a union grounded in one industry only cannot claim to be representative at the national level in France and Italy and can therefore not partake in national discussions. At best, it is allowed in these companies where it exists. Conversely, in Germany, as with IG Metall, unions seem to be grounded in one particular industry where they have full legitimacy to negotiate with employers (GumbrellMcCormick & Hyman, 2013). In addition to this, in countries such as France or Belgium, these unions are representative only when the law grants them this status regardless of their scores at workers’ elections. In these latter cases, there is what is called in French law a representativeness presumption (Schain & Kesselman, 1998). In return, political parties in most Western countries are only allowed in their mission statement and electoral programme abide by democratic principles and do not call the regime into question. For this reason, extreme right parties are allowed, unless they are proved Nazi of Fascist, whereby the Vlaams Block has been prohibited in Belgium and the New Nazi Party in Germany whilst monarchists are under severe scrutiny in France and Italy (Hainsworth, 2008; Mammone, Godin, & Jenkins, 2012). More broadly, a political party is allowed, provided its leaders and most active militants do not openly contest the democratic grounds on which the country is standing and does not openly call for a coup. It is because of such fears of a coup that opposition parties have been prohibited in a number of countries, such as China (Wu, 2015), Russia or Turkey (Goldner, 2018). Or, because of the Arab Spring, North African and Middle Eastern countries have been defiant of political parties seen as potentially bearing a revolutionary agenda (Badiou, 2012a, 2012b; Goldner, 2018). A second legal constraint on political parties and trade unions is that their existence and recognition are conditioned by their capability of being elected. That is, a union with no representatives in companies or a political party with no representatives at the Parliament, local governments or municipalities cannot exist. As such, they cannot have a voice in the public realm, since they formally do not exist. This regulation, though implicit, applies to all democratic countries, where an opponent only exists and can partake in public debates when his or her party has solid grounds. This rule was a problem in the French elections in 2017, as Emmanuel Macron was leading a young party founded a year prior and had no elected representatives. His party started to count only when established parliamentarians openly supported him and formally joined his party (Plowright, 2017). The same happened to Beppe Grillo in Italy when he initially launched his 5 Star party: no elected and representatives granted him no legal status and existence until they won seats at the Parliament and the Rome town hall (Tronconi, 2015). 1.7. Organisational constraints: mission and identity As non-profits do not necessarily operate in areas whence the public or the private sector is absent, joining such an organisation is usually grounded in good reasons. These tend to relate to organisation mission associated with a certain identity, if not ideology underlying the conduct of operations (Mintzberg, 1999). In numerous cases, non-profits’ members see in their organisation a – 13 / 41 – missionary engaging in the public sphere or even an advocate for a certain cause in public debates (Jenkins, 2006; Unerman & O'Dwyer, 2006b). Within this context, it becomes clear that members exert a form of control over the honouring of this quasi-political positioning. This ideology driving people’s joining is the common cement enabling the gathering of persons coming otherwise from different backgrounds. The best-known ideologies are certainly those that can be found in political parties or trade unions, since these openly defend certain values and interests. Political parties’ and trade unions’ mission consists of spreading their view of how the country, the local government or the company should be run, which often results in opposing those in office (Gumbrell-McCormick & Hyman, 2013; Pomper, 1992). In other types of non-profits, i.e. neither political parties nor trade unions, this ideology directly relates to the mission itself and the way it is or should be conducted. This can apply to arts: people join a classical music association because they love baroque music and would certainly not admit that contemporary composers would be played on their premises. In return, members of an association promoting contemporary or experimental music would not tolerate that classical music or popular music be played in their society. The same logic could apply to sport organisations. A rugby club playing by Australian rules would not encourage playing according to international rules. In return, a rugby club in Australia playing according to international rules would certainly not promote Australian rules. Outwith sports and culture, this logic applies to any other type of nonprofits, such as churches or charities involved in social work or education. In such organisations, mission and identity are a core constraint imposing itself. As members join because of this particular identity and mission, these impose themselves to management. Members at the bottom of the organisation place management under scrutiny, ensuring that these are making decisions consistent with core values. If management deviates from what members perceive as core identity and mission, they will be notified and maybe sanctioned. To some extent, mission and identity are at the heart of controls exerted from the bottom of the organisation, with management placed at its centre. Whilst the Panopticon effect is widely known and accepted in management control research (Armstrong, 1994; Brivot & Gendron, 2011; Cowton & Dopson, 2002; McKinlay & Pezet, 2010) the imperative of making goals converge leads to a Reversed Panopticon (Joannidès, Démettre, & Naudin, 2008). Through this Reversed Panopticon, management is placed under surveillance: at the centre of the organisation, his or her actions and decisions are visible to every single member. Accordingly, any deviation from what organisational members view as acceptable is immediately seen and can be sanctioned. In contradistinction to organisations from the public and the private sectors, identity and mission control are exerted from the bottom. How this Reversed Panopticon works is as follows. Management is placed at the core of the organisation, where every action is perfectly transparent and visible. Any organisational member can potentially view managers’ behaviour and actions, provided they look. Where they are placed, managers cannot see who is looking at them and if anyone is at all. This visibility should lead these managers to engage in self-control, so as to avoid bitter sanctions from organisational members in case of deviant behaviour. In return, managers in non-profits are constantly accountable to their members for their managerial actions. Such accountability can take numerous forms, depending on how structured and bureaucratic the organisation is. In relatively small and flat organisations with little bureaucracy, notifications of actions planned and undertaken may suffice. Such can be the case of a local football club for instance. Unlike this, when the organisation is larger and has strict procedures, management must apply for permission for certain decisions. Periodically, he or she has to justify these before the Board of Directors and annually before all members on the occasion of the Annual General Meeting (Herman, 2009; Roberts, Sanderson, Barker, & Hendry, 2006; Vaivio, 2006). Such can be the case of non-profits where management is professional, such as in most U.S. or British universities (Feldner, 2006; Firmin & Gilson, 2010; Parsons & Platt, 1973). The figure below summarises this Reversed Panopticon and associated surveillance of managerial actions. – 14 / 41 – Figure 3.4. The Reversed Panopticon Case n°5. Professionalising a soup kitchen Management under surveillance In a French soup kitchen, management wanted to anticipate volunteers’ availability by encouraging them to register for specific actions. In 2012, a first attempt consisted of sticking on the hall’s main wall a timetable with dates, hours and locations. Each cell in the table corresponded to a specific action: a certain soup kitchen in a certain place on a certain day at a certain time. People would register by writing their name in cells. Volunteers strongly rejected this initiative on the grounds that so doing was unfair on the organisation’s spirit. To them, their soup kitchen was built on mutual trust and benevolence, certainly not on control and constraint. They perceived this initiative as an attempt to control their assiduity and pressure them to do things in a certain way. After the first day, they expressed a strong disagreement and threatened the manager to depose him if he maintained this control. Management was forced to relinquish this initiative. In order to anticipate volunteer’s availability, he would only be allowed to ring a few people who would notably not perceived these phone calls as intrusive and controlling. – 15 / 41 – 2. Management control systems in non-profits Management control systems in non-profits take on forms very different from what can be found in private-sector organisations or in the public sector. In non-profits, controls are aimed at following up what is peculiar to these organisations in terms of financing, mission and the conduction of operations. They are not just aimed at ensuring goal convergence but also at discharging accountability to organisational stakeholders. Whilst, in other settings control, serves internal decision-making they also appear as a means of accountability to public and private donors as well as beneficiaries. Accordingly, these controls are twofold. On one hand, they focus on fundraising activities and outcomes; on the other, they scrutinise the conduct of operations and the righteous use of the resources collected. 2.1. Non-profits’ financing and performing The main area of control in non-profits unsurprisingly relates to the use of financial resources and thereby is intertwined with accountability to donors. Resources on which a non-profit can count proceed from four types of donors (Havens, O'Herlihy, & Schervish, 2006). 2.1.1. Public funding When non-profits operate as surrogates for public authorities in whichever field, they are missioned with a form of public policy conduct. In these situations, they are chosen by public authorities because of their knowledge of the local environment in which they are operating and on the grounds of their expertise at the dedicated public policy. Operating through public funding has a series of implications for non-profits’ functioning. These non-profits are publicly funded, which makes them explicitly accountable to public authorities for the use of taxpayers’ monies and the completion of polity programmes. Depending on the polity programme but also on the amounts of money at play and the type of non-profit, public funding can take three forms, implying three types of relationships to public authorities. The best-known public funding consists of subsidies and grants paid annually to these organisations for the conduct of their programmes. In this context, public authorities call on nonprofits and clarify with them what is expected of them in terms of activities. Non-profits’ management estimates what resources are needed, those being human, material or financial. Given these resources they already have regardless of demands from public authorities, they estimate for how much money they need to apply to be able to conduct the operations for which they are missioned. They submit their estimates to public authorities that decide to pay the required amount either in full or in part. The implicit assumption here is that these non-profits have already absorbed most of their fixed costs and need to clarify to public authorities what the variable cost directly relating to the mission shall be. Supposedly, public authorities shall pay the strict amount relating to this variable cost incurred because of polity programmes (Anthony & Young, 1994; Clemens, 2006; Young, 1994). In this case, public authorities can decide to pay the strict variable cost the non-profit shall incur for the conduct of this public policy programme or pay with a margin enabling the organisation to also fund its other activities (Rathgeb-Smith & Grønberg, 2006). The second form of public funding a non-profit can receive consists of a lump sum paid by public authorities for the conduct of public policy. This lump sum does not necessarily consist of a subsidy paid by public authorities. Rather, it appears as an estimate of the cost the public sector would have incurred if it had conducted this programme on its own. In this case, the non-profit is expected to organise itself in such a way that it can conduct the programme within the cost frame imposed by the public service, covering its variable costs and possibly some of the fixed costs the programme would imply. In this situation, the non-profit takes on the role any subcontractor to – 16 / 41 – public authorities would, as in the case of private-public partnerships or the Private Finance Initiative in the UK or Australia (Benito, Montesinos, & Bastida, 2008; Broadbent, Gill, & Laughlin, 2008; Froud, 2003; Shaoul, 2005). Behind this term is a form of private-public partnership that can be found in numerous other countries under different names (Broadbent & Laughlin, 2003; Grimsey & Lewis, 2005). The third option is rarer because it can lead to unpredictable costs for the public sector: a nonprofit charges the public sector for the service. In this situation, a non-profit is a surrogate for public authorities in a polity programme. The amount of money that the programme will ultimately cost public authorities is unknown; the non-profit conducts it and charges the public sector afterwards accordingly. The invoice can only account for the variable cost incurred by the nonprofit for conducting this programme. Whichever form of public funding is chosen, public authorities pay a certain amount of money to non-profits for the conduct of a public policy programme. As most of these practicalities imply the funding of variable costs only, these non-profits need to have a management control system enabling them to account at least for their variable costs. Not only do they have to account for their total variable cost, they also need to specialise their costs by activity or programme. Thence, not just a variable costing system is required but also an Activity-Based Costing system (Sajay, Covaleski, & Dirsmith, 2009). This ABC system has a purpose differing from that of private-sector companies: in these latter, ABC supposedly serves management helping compute the costs the organisation incurs. In a non-profit, it serves to determine whether an activity, especially financed through pubic funding, can be undertaken without putting the organisation at financial risk. 2.1.2. Membership funding The second best-known source of funding for non-profits consists of self-funding through fees and donations received from members. Such is the case of most clubs, societies and associations, where membership rests upon the payment of an annual fee allowing to partake in activities. Unlike non-profits delineating polity on behalf of public authorities, these membership-based organisations provide their members with a service (Anheier & Salamon, 1994, 1996, 1997). Depending on the non-profit’s activity, its public and the overall costs incurred, membership fees can be more or less high. Traditionally, non-profits benefitting from public subsidies can require a relatively low membership fee whilst those that are not otherwise publicly funded tend to apply higher fees. In some other cases, the non-profit is just a legal form allowing people to gather. Through this legal form, members can be insured in case any problem occurs. In this particular case, the organisation itself does not incur particular costs and only charges its members to cover various membership costs. Sport clubs just utilising publicly available equipment and counting on volunteer coaches and only needing minor assets for the conduct of operations, such as balls or after-game refreshments, can charge their members a little amount of money. The same can apply to societies gathering at members’ place or in other spaces where they are not charged (e.g. a café, a public garden, etc.). Such non-profits are for instance literary societies or book clubs, home leagues, or school kids’ parents’ societies, etc. Some other non-profits benefitting from no public funding could apply high membership fees. Such is the case when the organisation incurs high fixed costs and has to cover them through its members’ contribution. This situation occurs with some very private, exclusive clubs and societies gathering in their own spaces (buildings, hotels, restaurants, etc.) This can also happen in the case of non-profits doing activities requiring significant assets (e.g. buildings, equipment or highly qualified employees). Such exclusive non-profits are common in sports (e.g. tennis clubs, golf clubs, polo clubs) where estate, equipment and professional training are central. – 17 / 41 – In either case, the non-profit needs to count on a more or less developed management accounting system whereby the costs incurred can be estimated. Thence, membership fees can cover these costs. In the first case, membership fees shall cover the mere variable costs; in the latter case, membership fees are also supposed to cover fixed costs. Some other non-profits doing charitable giving in their own name may require that their members pay a high fee enabling their donations. Such can occur in societies such as the Rotary or the Lions Club (Martin & Kleinfelder, 2008). In this particular case, the management accounting system is more aimed at tracing donations made rather than costs (Anthony & Young, 1994). This exception these organisations represent is such that they act as sponsors to other non-profits and therefore are the one to whom accountability must be discharged. That is, their direct concern lies in tracing the righteous use of funds entrusted to other non-profits: economy, efficiency and effectiveness. In sum, these particular non-profits operate like trustees financing others and thereby exerting an external control over these. Within this galaxy of non-profits, three types thereof deserve a special treatment: churches, political parties and unions. Most churches can generally count only on their members’ generosity (Irvine, 1999, 2002, 2005; Lightbody, 2000, 2003). Of course, there are some exceptions to the rule: the Roman Catholic Church, which can benefit from international clerical funding, or officially recognised churches receiving public funding in certain countries (e.g. Sweden, Germany, Switzerland, or the UK). In the general model, these churches do not charge their members a certain fee but live off the donations they receive from them. These can consist of donations during services, responses to particular appeals, bequeaths or any other personal donations (Joannidès, 2009). A church is a particular case of non-profits, insofar as members’ generosity usually rests upon certain emotions driving the believer and cannot be explicitly fostered or suggested and therefore difficult to anticipate. In such a church setting, management accounting mostly consists of budgeting day-to-day activities at the least cost, hoping that members will contribute sufficiently to cover the cost of activities (Irvine, 2005). This is especially vivid in local congregations whilst larger denominational churches have other sources of funding, discussed later on in this chapter. The funding of political parties and unions represent another two exceptions to non-profits’ financing. Unions clearly represent and defend their members’ interest. In most countries, unions are therefore funded only through the annual fees paid by members. In this case, the fee paid is generally a very low percentage of the salary received. In some countries, where unions are not just recognised but do have a real negotiation power, the fee can be directly debited monthly from the members’ account. This is the case in Scandinavian countries, Germanic countries, the US, the UK, Australia or New Zealand. The phenomenon is accentuated when membership in a union is compulsory, in which case the monthly fee appears on the payslip almost as any tax payment. Conversely, in countries where unions are weaker or not very institutionalised within companies, the fee paid tends to be a paid by the member him-or-herself (Gumbrell-McCormick & Hyman, 2013). This case can be found in France and Belgium. Monies collected from members serve to finance information flyers addressed to all members, costs of public protests (freighting coaches to a protest place, bandwagons and other accessories) or the possible cost of major strikes. By definition, protests and strikes, which are major actions, cannot be predicted or anticipated, making budgeting if not impossible at least a difficult task. Therefore, management accounting focuses on the securing of resources over time, with financial managers appearing as guardians of organisational resources (Lightbody, 2000). This securing rests upon the following two pillars. Firstly, financial managers are tasked with the tracing of the number of members and their wages so as to anticipate their fees. Secondly, as a union only exists through its members, management accounting traces ways and means of attracting new members and retaining current ones. Political parties’ financial concerns are quite similar to those of trade unions with two major challenges. The first one is that political affiliation and activism may be much less attractive to people than involvement in a trade union. Accordingly, political parties are likely to count fewer members funding their actions than unions. Whilst these latter directly serve their members’ – 18 / 41 – interests political parties do not. This implies that political parties may need to find other sources of funding and donors than mere members (to be discussed in the subsequent subsection). The second challenge proceeds from this one and lies in the fact that political parties have to face electoral campaigns and elections that are known in advance. Thence, management accounting in a political party has a twofold focus. The first consists of estimating of how much electoral campaigns shall cost and how much extra funding will be needed. The second focus is more conventional, as any other organisations and consists of tracing expenses. More particularly, owing to the difficulty to raise funds, expenses’ destination needs to be expressly identified and connected to an operational concern on the political agenda. In other words, any expense must be justified through its contribution to the political battle (Pomper, 1992). 2.1.3. Private donors and sponsors The role played by some generous donors or philanthropists often reveals spectacular actions, with people leaving massive estate and properties or bequeathing their inheritance. As private donating and sponsoring are multifaceted, it is important to draw donor profiles and specific associated issues for management control and accounting. For each type of donor would a management accounting concern arise. 2.1.3.1. Donors’ profiles and expectations The main type of private donations non-profits can receive proceed from philanthropists, i.e. generous donors (Liket & Simaens, 2015; Liu & Baker, 2016). Philanthropists tend to donate to non-profits operating mostly in healthcare, social care, education as well as arts and culture (Gautier & Pache, 2015; Vesterlund, 2006). In these areas, three practicalities reflecting three profiles of philanthropists emerge. The most spectacular profile is that of a wealthy entrepreneur donating a massive amount of money to charities under whichever form. The most famous philanthropists falling within this category are U.S. billionaires who, following Warren Buffett’s initiative, decided to donate half of their fortune to charities acting in the aforementioned fields (Shirley & Askiwith, 2013). These include George Soros, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg and a series of others. After having donated massive amounts of money to non-profits, some of these philanthropists launch their own foundation which they fund through their own wealth, as with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Sobanjo-ter Meulen et al., 2015). The second best-known profile of philanthropist is that of successful professionals, not necessarily as wealthy as in the first category, who decide to bequest their properties to a non-profit after they decease. These legacies can consist of various assets including estate, properties, artworks, bank accounts, security portfolios, life insurance contracts, etc. Depending on the cultural variation of welfare Capitalism in which they are active – Anglo-Saxon, Latin, Germanic or Scandinavian –, the rationale for bequeathing their fortune can vary. In continental European countries, where inheritance and heritage properties are parts of culture, bequests tend to be more the fact of elderly people with no official heirs. In U.S. and Australian settings characterised by a hard-work and selfmade culture, wealthy parent have traditionally donated their fortune to non-profits, letting their children making theirs on their own without counting on family assets (Behling, 2018; EspingAndersen, 1992). In either case, bequests, legacies or major donations cannot be anticipated, unless these donors explicitly share their wills with the targeted non-profits. The third profile is less easily detectable, since it consists of people responding to one particular appeal launched by a non-profit. Specific appeals are often launched by non-profits seeking to partake in a relief action and needed funding for this. Usually, numerous non-profits are called for and raise funds to be capable of responding to this particular crisis. Appeal examples can be those launched by the International Red Cross, Care or the Salvation Army after the 2010 earthquake in – 19 / 41 – Haiti (Salvation-Army, 2010), the need for volunteers to retrieve and aid September 11 victims (Feinberg, 2006), or the 2004 tsunami in Phuket (Schultz, 2015). When such crises arise, these nonprofits are immediately solicited because they can response very quickly: they can raise funds enabling them to send volunteers, professional relief specialists, materials, equipment and humanitarian aid. Donors may be people feeling directly concerned with the event occurring and willing to contribute (Havens et al., 2006; Sargeant, 1999; Vesterlund, 2006). Targeting the public, these campaigns may result in smaller amounts being donated, multiplicity making the difference. Outwith individual donors are corporate sponsors financing non-profits. These fall within three groups, highlighting three profiles. The best-known profile is that of private businesses sponsoring certain non-profits on an ongoing basis. This first profile is an expression of corporate social responsibility policies (Liket & Simaens, 2015; Wulfson, 2001). Thereby, a private company contributes to a social or environmental project borne by a non-profit and associates its name thither by financing it. As discussing the sincerity or spontaneity of such donations is outwith the scope of this chapter, these issues will not be discussed here. For instance, McDonald’s is funding a foundation fighting obesity and infantile diseases. The second profile consists of private companies financing specific, recurring events organised by non-profits and to which they can associate their name and brand. In this case, the corporate sponsor spreads its brand through an event deemed compatible with it, if not seen as an extension thereof. Whilst the first profile appears as a way of gaining social or environmental credits the second profile can more be seen as targeted advertising campaign through a non-profit (Sargeant, 1999). Such can be the case of luxury brands financing some exclusive sport events organised by non-profits, such as Longines Watches sponsoring a world-class horse-riding contest (https://www.longines.fr/univers/actualites/longines-speed-challenge-at-the-longines-mastersof-paris). The same could apply to Rolex sponsoring major world class events in horse-riding, golfing, formula 1, tennis and sailing (https://www.rolex.com/fr/rolex-and-sports.html). The third profile of corporate donors is specific to political parties. Some companies openly support a party or a candidate for a major election, e.g. the presidential election in the U.S. and in France, or the Prime Minister in the UK. In order to facilitate the implementation of a political programme consistent with their values and interests, these corporate sponsors do finance in part or in full an electoral campaign (Pomper, 1992). In case the supported candidate wins the election, this latter should find him-or-herself indebted to these corporate funders and supposedly defend their interests (Zetter, 2014). Such can be the case of the National Rifle Association in the US regularly funding the campaign of candidates rejecting gun control in the country (Street, 2016). 2.1.3.2. Issues in management accounting The specific case of responses to appeals highlights major concerns for management control and accounting. Donors do give not to a non-profit in general but for a specific purpose involving an non-profit organisation. That is, private donors respond to a specific appeal because they feel concerned with a specific event. Accordingly, the main challenge confronting non-profits’ management accounting system is that the monies received are eventually utilised for the conduct of this particular programme. If some of the funds donated have not been utilised, they can supposedly not be used for any other project, since they were given for this one in particular. That is, non-profits cannot afford to raise funds too much exceeding their actual needs. This has major accounting implications. Firstly, the non-profit must raise funds on the basis of a comprehensive forecasting model, setting a collection target and terminating the campaign when it is met. This implies that the scope of nonprofit’s mission be perfectly clear at the outset, hence it is possible to anticipate how much money is needed. Defining the scope of a non-profit’s action appears as functional, temporal and spatial: what is expected of this non-profit, where and for what period of time. It is because this scope is clear that the non-profit can estimate its financial needs (Anthony & Young, 1994). – 20 / 41 – Secondly, in order to avoid dormant monies that cannot be utilised for any other purpose, a fundraising campaign must be associated with an ultimate total collection target and interim objectives. To this should warnings be added, in order to be notified when the target is about to be met. Accordingly, the campaign can regularly be temporarily suspended, until management accountants determine the pace at which the total amount can be collected and progressively prepare the end of the fundraising campaign (Kelly, 2012; Pawson & Joannidès, 2015; Sargeant & Shang, 1999). The issue confronting non-profits is that they cannot return excessive money to donors, and this for two reasons. The first reason for this impossibility is that of the grounds on which excessive monies would be returned to donors. Should there be an allocation rate based upon whichever criteria pursuant to which each donor would receive part of their initial donation? Would certain donors be privileged and paid back in priority? According to what criteria? The second reason arises, assuming that an allocation rate may have been found: as non-profit’s financing is often associated with fiscal incentives, returning their monies to donors would have major financial and fiscal implications. Donors based in countries where donations to non-profits open for tax exemptions and deductions, retrieving their donation back may alter their fiscal situation and result in them retroactively paying unexpected tax. In countries, such as the UK, where the government matches donations received from philanthropy, the non-profit would have to reimburse the tax office, which could affect its financial sustainability. Thirdly, management accounting is expected to periodically produce figures of collection targets associated with actual collection and expenses. Under the purview of proving donors that their monies have been used righteously, the non-profit periodically sends to each of them a note summarising the following (Kelly, 2012; Sargeant & Shang, 1999): - collection target; - actual collection as of a certain date; - expected additional collection; - operational achievements; - how much of the donation received has been utilised as of this date. In the particular case of responses to appeals, management accounting enables the discharging of accountability to donors, by highlighting on an ongoing and continuous basis how resources collected has been utilised. Accordingly, in order to avoid excessive fundraising and monies impossible to spend, it is often recommended that non-profits set targets lesser than their actual needs, the assumption being that they will always find the necessary resources (Kelly, 2012; Sargeant & Shang, 1999). The implicit assumption is that there will always be generous people in a capacity of making an extra effort if required (Havens et al., 2006; Vesterlund, 2006). Fourthly, management accounting helps in the preparation of annual disclosure to donors. Here, it is management accounting that plays a central role rather mere financial reporting abiding by standards. Although financial reporting offers an aggregated view of the non-profit’s financial situations and health, it does not allow them to highlight what has been specific to their activity. In particular, ad hoc programmes, such as responses to appeals, cannot be made easily visible to donors. Accordingly, annual disclosure also builds upon data from management accounting by detailing each programme, highlighting fundraising objectives and actualisations as well as operational achievements (Gray, Bebbington, & Collison, 2006; Jayasinghe & Wickramasinghe, 2006; Unerman & O'Dwyer, 2006b). Case n°6. The 2004 Tsunami in Phuket, Indonesia The Red Cross two-step scandal On December 26 2004, a tsunami devastates the Phuket Island in Indonesia, causing destructions, people missing and other casualties. Immediately after the event took place, – 21 / 41 – international non-profits launched fundraising campaign for relief actions in the region. Amidst these non-profits were the Salvation Army, Care and the Red Cross. In order to allow generosity from all over the world and for any organisation willing to participate in this relief mission, each of them was commissioned with a specific task within a specific geographical area and for a certain period of time. Owing to its international reputation and connections, the Red Cross managed to raise massive amounts of money. After six months, in June 2005, it was noticed that the Red Cross still had 2 millions euros unspent whilst numerous areas in Indonesia were still in deep need. This was the first scandal confronting the Red Cross: as its mission was terminated, the organisation still had excess resources without being allowed to reuse them for any other purpose. At the same time, other non-profits were struggling to finance their field operations. Given its commissioning, the Red Cross was not allowed to trespass on these organisations’ mission. The scandal was that these 2 millions euros found themselves idle although they were dramatically needed. The scandal took a second turn in December 2005 when the Red Cross conducted follow-up missions in Phuket. Having these 2 millions euros in hand for this specific relief programme, the organisation was obliged to spend it all. This resulted in volunteers being flown first-class and accommodated in expensive hotels. The scandal was that these people volunteering for a non-profit were unduly benefitting from international aid whilst needy people in Phuket remained unhelped (Schultz, 2015). This two-step scandal occurred to a great extent because the Red Cross’ management accounting system had not enabled an accurate anticipation of collections and certainly underestimated donors’ generosity. Since this event, when launching appeals, non-profits have added a box to their forms asking permission to reuse excessive funds to other programmes. Such is done so that, if donors tick this box, the organisation is not committed to utilising all the funding received for this specific purpose. Conversely, if donors do not agree, the non-profit is constrained to spend their donation in priority and inform them thereof. 2.1.4. Commercial activities The last and least known source of financing for non-profits consist of revenues generated from commercial activities. Very often, there is confusion as to non-profits’ status leading to mistakenly believe that, because they cannot share profit, they cannot have lucrative activities. Such confusion is probably more vivid in the general public than in research and corporate circles (Hardy & Ballis, 2013). Yet, numerous non-profits, especially those operating in a circumscribed area, do have commercial activities. Some are especially known, such as White Elephant Sales in the UK or New Zealand, garage sales in the U.S. or Australia or thrift shop sales in most countries in the world. Most charities do organise such op-shop sales, since these generate resources that can be used for the conduct of organisational core programmes. The Salvation Army, Oxfam, Emmaüs and many others (Haegele, 2012). Non-profits can also generate resources from recurrent commercial activities, especially in relation to their services. When they own properties and estate, they can generate revenue from leasing them, thereby acting as social landlords. In places, families a minimal rent for dwelling in a place owned and managed by a non-profit. Low rents are often made possible because these properties were received from generous donors or bequeathed. Thence, even minimal, the rent perceived allows to fund other programmes run by the organisation. Other commercial activities conducted on the side of these can generate resources, such as hospitality on estate these non-profits own. Such can be the case at the Salvation Army William Booth training college for officers in London, – 22 / 41 – where visitors can book rooms and pay nightly for their stay in this quasi-hotel run by the organisation (Joannidès, 2009). Lastly, non-profits can generate resources from their publishing activities. Many non-profits do publish books, newspapers and magazines they are selling. In these outlets, these organisations do not just communicate on what they do; they also share some tips and secrets with their readership: personal testimonies in books, other cooking recipes in magazines, colouring books for children with their activities… Some other non-profits do sell goodies and accessories with their logo, such as clothes, tea towels, napkins, key rings, memory sticks or any other thing the public could purchase. As in any other organisation, revenues generated from the commercial activities can be more or less anticipated. For recurrent activities and revenues, non-profits’ management accountants can relatively easily forecast how much money may be earned annually, by building on previous years’ figures. In this case, as compared to private companies’ forecasts, it can be assumed that these nonprofits can count on recurrent ‘clients’ supporting their activities by buying goodies. Thence, it is not necessary that these organisations build sophisticated forecast models (Anthony & Young, 1994; Anthony & Herzlinger, 1975). Also, most of the time, these non-profits do not make their goodies themselves. Either they buy them from external suppliers or are offered these by some supporting companies. In either case, sales happen as these products’ total cost plus a profit margin. As these products do rarely represent high amounts of money, management accounting mostly focuses on volumes sales and the surplus generated from these sales (Anthony & Young, 1994; Anthony & Herzlinger, 1975). 2.2. Operational audits and controls In contradistinction to a commonly agreed idea, management control systems in non-profits do not just serve day-to-day decision-making. Accordingly, management control systems in nonprofits do not only consist of conventional controls but appears as the intertwining of external and internal controls. These former focus on the righteous use of money and effective mission conduct; the latter emphasise the convergence of individual goals with organisational objectives under external accountability constraints. 2.2.1. External operational and financial audit In contradistinction to a commonly accepted idea that management accounting serves for managerial decision-making only and is not supposed to be shared outwith organisational premises, such is not quite the case in non-profits. In these organisations, owing to the fourfold means of goal convergence control, management accounting appears as an information system with a dual objective. In the first place, management accounting indeed play a traditional internal managerial role (Anthony & Young, 1994; Anthony, Dearden, & Bedford, 1984; Anthony & Herzlinger, 1975). Secondly, it contributes to the discharging of accountability to donors of all sorts or public authorities (Joannidès et al., 2015; Joannidès, Jaumier, & Le Loarne, 2013; O'Dwyer & Unerman, 2007; Unerman & Bennett, 2004; Unerman & O'Dwyer, 2006a, 2008). 2.2.1.1. Specialised auditors Donors of whichever sort are considered central stakeholders to the non-profit organisation. In this capacity, some social accounts specific to their requirements and expectations need to be produced. Such accounts are not necessarily financial or, when financial, not systematically aggregated figures. This idea contradicts a certain amount of publications on non-profits’ accounting and accountability emphasising either financial reporting and disclosure, summarised as what needs to be accounted for (Christensen & Mohr, 1995, 2003), how this can be done – 23 / 41 – (Connolly & Hyndman, 2000, 2001; Hyndman & McDonnell, 2009) or income statement construction under with the objective of reporting no surplus (Cordery et al., 2011). Rather, management accounting can serve to prove the systematic effectiveness of resources use by showing how monies, depending on their origins and destination, are eventually spent for the purpose for which they were donated (Joannidès et al., 2015; Joannidès et al., 2013). Something of particular interest here is that financial reporting standards are seen as failing at doing this, which concurs with Connolly & Hyndman’s (2001) findings that such standards are far from being systematically used by charities. It does seem that a reason for such a situation could be that financial reporting standards offer an aggregated view of the organisation and does not allow to grasp the specificities of activity contents. This might also help understand why the Irish charities studied by Connolly & Hyndman (2001) tend not to apply these standards. Seemingly, management accounting and more broadly management control systems can support accountability’s discharging through the identification of what counts for stakeholders (here public authorities), as well as how this should be counted and recounted. In the particular case of non-profits acting as surrogates for public authorities, a form of technocratic accountability grounded in management accounting and controls arises (Morgan, 2006). Governmental agencies control two areas of non-profits’ activity, which mere financial reporting can hardly reveal. The first realm of external audits and controls relates to government’s accountability to citizens for the keeping of the electoral promises made. It is therefore a control of polity execution. To this end, the most common approach consists of sending operational auditors from the ministry under whose responsibility this non-profit’s activity falls (Joannidès et al., 2015; Joannidès et al., 2013). If the non-profit operates in the field of education, auditors are sent from the Ministry for Education; if the organisation operates in the field of healthcare, auditors are sent form the Ministry for Health, etc. These auditors are unsurprisingly specialists of the area in which the non-profit operates and basically control operations at two levels. 2.2.1.2. Public policy execution controls The first layer of controls is at the Headquarters, where the operationalisation of every standard set by the Ministry is scrutinised. This leads external auditors to focus on the effective honouring of standards and regulations on one hand and on results on the other. On the former issue, as the non-profit is acting on behalf and in the name of governmental authorities, it is required to delineate public policy in a certain way, as close as possible to what the public sector would have done. Accordingly and depending on the public policy area, ministerial auditors control the adequacy of staff skills and qualifications with prescriptions from the ministry, internal business processes and service quality. The second level at which external operational auditors exert controls is that of grassroots operations. Not just aggregated outputs and formal processes are scrutinised, but also how things are done on the battlefield. As with conventional audit operating within a risk perimeter (Broadbent et al., 2008; Froud, 2003; Hanlon, 2010; Knechel, 2007; Mikes, 2009), ministerial auditors would select a range of business units they want to investigate. As with conventional audit, they visit these units, browse the available and relevant documentation, observe how things are done and may interact with grassroots actors (beneficiaries, employees, volunteers). In so doing, they would verify that, at the most local level, official operational and quality standards are eventually applied and followed. In the first place, qualification and skill control is especially central when the non-profit is operating in an area where the public sector could do the same and when the public’s health and safety are at stake. Therefore, in any educational activity, teaching staff qualifications and skills are periodically controlled. This results in controls focusing on the HR department and its practices (staff allocation, staff training, etc.) Likewise, in healthcare and social care, qualification and skill – 24 / 41 – control consists of matching what is officially required with nurses’ and other social workers’ actual initial qualifications and continuous training. The same logic applies to any other area of direct interest to governmental authorities. The second area of operational control addresses the contents of the mission itself and how it is executed. As the non-profit is an operational extension of the public sector in numerous areas, how things are done is especially important to governmental authorities. In many cases, the outsourcing of certain activities to non-profits rests upon the assumption that these organisations have a certain level of expertise that the public sector does not internally have. Therefore, it is periodically controlled that such is still the case. Accordingly, public auditors pay attention to the procedures followed internally to do things. Books of procedures, reports of activities sent to the headquarters are checked so as to make sure that the official way of doing things is well honoured. In places, this may lead to control the very contents of what is being done in the non-profit, these operating as a servants for the diffusion of governmental ideology (Robson, Willmott, Cooper, & Puxty, 1994; Rodrigues & Craig, 2009). In schools run by non-profits, this can take the form of controlling what is taught in comparison to official school programmes. Textbooks, lecture notes can be checked and complemented by interviews with teaching staff, pupils and parents. In arts and culture organisations, auditors from the Ministry for Cultural Affairs would control that a certain approach to arts and culture is diffused (DiMaggio, 2006). The nature of what is exhibited in an art gallery can be controlled, material likely to shock the public being potentially subject to an official removal order. The third area of ministerial audit would focus on outputs. More than the results per se, what becomes important to governmental authorities is twofold. On one hand, a major concern is that the quantified promises made during the electoral campaign be kept. Accordingly, these auditors shall trace facts and figures that governmental authorities could claim as their achievements. Depending on the public policy area and governmental authorities’ core concern, these achievements can be expressed in quantitative or qualitative terms. In the case of social care nonprofits dealing with the placement of unemployed people, the number of people effectively placed will be emphasised. If the non-profit meets the publicly set objective or outperforms, governmental authorities can claim this as an achievement for their policy. In the case of schools run by nonprofits, ministerial auditors would follow success rate to university admission. Sport organisation’s achievements could be the final rank at a certain competition or the number of active members… Or, as discussed in case n°1 with the example of the London Olympic Games Organising Committee, the output would be assessed through the final decision made by the International Olympic Committee to grant London the organising of the Olympics, which corresponded to an electoral promise made by the Prime Minister and the Mayor. On the other hand, the output control exerted by ministerial auditors can operate like quality control, which can be perceived similarly to total quality management in private sector organisations (Hoque, 2003; Ittner & Larcker, 1997; Johnson, 1994). Added to internal process controls, output control enables in the very case of non-profits to ensure that organisational expertise is still vivid (Anthony & Young, 1984; Young, 1994). The implicit assumption is that satisfactory achievements rest upon good quality work and organisational processes. Whichever method is chosen to assess outputs from non-profits’ activities, these raise an as yet unresolved issue of what deserves to be measured and how this should be done. 2.2.1.3. Money usage control The control of how monies entrusted to non-profits is certainly the most-known activity of external auditors. This form of control is especially vivid when non-profits are not acting as surrogates for governmental authorities. In this case, two types of external financial audits take place. The mostknown form is that of professional external auditors and approving organisational financial reports. The main weakness research has highlighted lies in that theses reports are built on financial – 25 / 41 – reporting standards whose contents are not necessarily relevant. The aggregated figures produced do give a glimpse of the non-profit’s financial situation and health but do not allow to trace the usage of the monies the organisation has been entrusted. In addition to compulsory conventional auditing, it is not unusual that major private or corporate sponsors do commission their own auditors to verify internal controls and financial management (Anthony & Young, 1994; Anthony & Young, 1984; Young, 1994). These auditors visit the headquarters and investigate the management accounting system and financial management. As with conventional auditing, these external controllers would set a risk perimeter and focus only on this. Within this perimeter, commissioned controllers do verify for certain donations the following: - collection target; - actual collection as of control date; - expected additional collection; - operational achievements; - how much of the donation received has been utilised as of control date. These controls also emphasise the correspondence between the organisation and concerned stakeholders, i.e. letters and reports periodically send to them (Unerman & O'Dwyer, 2006a, 2008). Data is then triangulated with programmes’ management accounting figures so as to verify their reconciliation. Such bureaucratic controls exerted from external auditors would occur in large nonprofits counting on high donations from major donors, since there is a real issue in them having their name associated with this or that particular organisation (Brown & Caughlin, 2009; Luidens, 1982; Morgan, 2006; Rothschild-Whitt, 1979). Such external audits are aimed at either averting the advent of financial scandals in non-profits or at least detect them at the earliest possible stage of their occurring (Bou-Chabké, 2016; Taha, 2013). In the particular situation where a non-profit acts as a surrogate for governmental authorities, public auditors can be sent to do conduct these investigations. Depending on the country and on the sensitivity of public policy delegations, these auditors can be sent either from the supervising ministry or from a different one. When sent from a different ministry, public auditors are tasked with a public interest mission: controlling the righteous use of public monies (Joannidès et al., 2015; Joannidès et al., 2013). Case n°7. The Salvation Army – denomination or charity? Public auditors’ control of public monies’ destination The Salvation Army was founded in 1867 in London’s poor districts by a Methodist pastor, William Booth. Following his recognition of the fact that needy people were perceived as troublemakers, he quit the UK Methodist Church and decided to found a congregation in which they would be provided with temporary emergency aid (i.e., soup kitchens and a shelter for homeless people). In parallel, social workers plan perennial and sustainable social inclusion programmes; hence, they can quit their condition as social outcasts and witness to the miracle of their new birth. All of the above is aimed at making those people receptive to the Gospel. According to the founder’s theology, churchgoers must be involved in their church’s social work either as volunteers or employees. Social work with no religious foundation would make very little sense to the Salvation Army because that would not match its identity. In turn, spiritual coaching with no social work would also not be consistent with the Salvation Army’s identity. It does appear that the intertwining of these two pillars is central to the Salvation Army’s accountability system, proving that social work is grounded in faith and that faith leads to social work. Given the accumulated knowledge and expertise in handling misery, exclusion and poverty, the Salvation Army has progressively become a surrogate for numerous governments in the conduct of social policy, particularly temporary emergency aid and social outcasts’ social re-socialisation, manifested in the constructing and following up of individuals’ – 26 / 41 – plans for a second life and inclusion into society. In France, as a surrogate for social services, the Salvation Army can count on c. 2,000 employees and 3,400 volunteers in 171 centres and congregations to assist almost 150,000 people. The conduct of these operations is enabled through public funding amounting to up to 76 per cent of its resources, in which public money accounts for approximately 130 million euro of a total of approximately 160 million euro funding. Thus, it is no surprise that in France, the Salvation Army's proof of accountability is primarily directed at French governmental authorities and focuses on public policy matters to which the organisation is legally committed. Due to its hybrid identity as both a denomination and registered charity, accountability raises numerous legal and control issues. These issues provide the basis for board discussions around the design and implementation of an accountability system aimed at providing the government with evidence of the Salvation Army's commitment to using public monies specifically for public policy matters. This accountability system is this paper’s empirical concern. The legal problem confronting the Salvation Army in its discharging of accountability to public authorities is known in French as laïcité, a philosophy unique to France. In effect, on December 9, 1905, the French Parliament issued a law separating the State from religion; its first paragraph states, The Republic does neither recognise nor employ nor fund any worship. Consequently, every expense related to the practice of a religion will be removed from the budget of the State, counties and municipalities. Public manifestation of religious affiliation and any public funding for religious organisations and activities is prohibited. However, religious freedom is guaranteed, which justifies the fact that the French authorities recognise no religion. Recognising no religion is manifested in the French authorities granting no monies to religious denominations for any purpose. This principle was reaffirmed by a law passed by the French Parliament on February 10, 2004, confirming this prohibiting of manifest signs of religious affiliation in the public sphere, particularly in schools, hospitals and any other public service and prosecution of trespassers. On 19 June 2000, the Territorial Commander convenes a board meeting. The 14 board members and the TC’s personal counsellor are present. The meeting is open to the sharing of a major concern: Auditors from the Home Office visited us last month. They thoroughly looked at all our processes. They inspected our homes in order to see how we manage to keep religious matters in a strictly private realm. In the report they submitted to the Home Minister and the Minister for Social Affairs, they stressed a major ambiguity in our way of doing things and completing our mission […] Laïcité is our legal constraint. Supposedly, the Salvation Army should no longer be funded by public authorities. However, as we are the main partner of the Ministry for Social Affairs, the government has found a solution; our social work can still be funded but our religious activities cannot. This can be the case, provided we find a way of proving that the money we are granted is directed towards social work only. Accordingly, this meeting’s purpose is to reflect on such a solution. This meeting was the commencement of a reflection on the design of a management accounting system enabling to prove that public monies are used only for a social work purpose (Joannidès et al., 2015; Joannidès et al., 2013). 2.2.2. Internal controls and performing’s performance Notwithstanding the effect of a Reversed Panopticon subjecting non-profits’ general management decision-making and orientations, larger organisations tend to develop their own internal control systems. Although these serve mostly day-to-day internal management and help managerial decision-making (Anthony & Young, 1994; Anthony & Herzlinger, 1975; Anthony & Young, 1984), they appear as a way of tracing that a form of operational accountability can eventually be discharged to the relevant stakeholders (Joannidès, 2012; Laughlin, 1996). That is, what employees – 27 / 41 – and volunteers do needs to be tracked and followed up, since management is ultimately to give their stakeholders a full account thereof. The grassroots person, be he-or-she an employee or a volunteer finds him-or-herself as a moral and responsible self seeking to witness the truth, so that others have faith in him or her. Traditionally, such truth and fairness can be found in stockholders and investors basing decisions upon faith in financial disclosure (McKernan & Kosmala, 2004). This operational accountability requires that management be in a capacity of demanding employees and volunteers an account of what they do, how they do things and how they do these in a certain way. That is, management appears as organisational internal superior authorities deemed legitimate to demand accounts and conduct investigations if need be. In the particular case of non-profits, top managers are to give good reasons for conduct to and markets and finance providers who gather at annual general meetings and other events. On these occasions, such managers take instruction, directly from their higher principals and subsequently render accounts to them (Roberts et al., 2006). This can also be the case in a religious context where the faithful are constituted as open, responsive, and accountable to God (Derrida & Wieviorka, 2001). Organisational authorities are considered to have the legitimacy to define policy and doctrine reflecting the requirements of the higher principal and to compel people to conduct themselves accordingly. Non-profits’ volunteers and employees find themselves compelled to follow prescribed procedures when doing things and accounting for conduct in order to facilitate superiors’ control of accounts and behaviour. When accounts of conduct are given to a hierarchic superior, prescriptions from the organisation management control system are followed in day-today accountability (Ahrens & Chapman, 2002). Thence, numerical figures can provide the higher stakeholder with a visual, memorisable representation of how resources are used in the conduct of business operations. These accounting records are coupled with words that, in the worst case, merely label them and, in the best case, make sense of them to tell an intelligible story (Quattrone, 2009). In face-to-face meetings with investors, comments on numerical figures are demanded from accountable managers: questions are asked and satisfactory answers are expected (Roberts et al., 2006, p. p.283). It is commonplace to consider that external stakeholders require financial accounting figures, in order to appraise how public monies were utilised. In the case of listed companies, these are financial analysts or any investors interested in knowing how much value was created through the proper use of the Higher-Stakeholder’s (economy subrogated by capital markets) funds (Jupe, 2009). In the case of an non-profit, external stakeholders are generally considered donors and public authorities, the Higher-Stakeholder being the public and the beneficiary (Goddard & Assad, 2006; Gray et al., 2006; Lehman, 2007; Unerman & O'Dwyer, 2006a, 2006b, 2008) interested in quantifying the welfare produced for the social body. In other words, they do seem to demand accounts for the righteous use of donations, i.e. for the completion of the announced programmes (training, social work, soup offered, etc.) Lastly, public organisations disclose accounts revealing how taxes collected and returns on public investments were used to construct infrastructures or enable social transfers (Black, Briggs, & Keogh, 2001; Broadbent, Dietrich, & Laughlin, 1996; Collier, 2005; Ezzamel & Willmott, 1993; Humphrey, Miller, & Scapens, 1993). In all these cases, accountants are expected to respect generally accepted accounting principles, viz. routinised norms for the accountability practice. Within the organisation, managers subrogate the Higher-Stakeholder through demands for accounts of actual everyday life, employees accounting for what counts (Ahrens & Chapman, 2002, 2007; Ahrens & Mollona, 2007; Jørgensen & Messner, 2009). In fact, subordinates are expected to provide managers with management accounting figures, which can also comprise of non-financial data, if these are an acceptable and reliable representation of the organisation strategy in practice. In a private sector organisation, such figures can address costs and income, number of units produced or sold, per unit value, inventory, or delivery velocity (Armstrong, 2002; Hopper & Armstrong, 1991; Vamosi, 2005; van Tries & Elshahat, 2007; Wickramasinghe, Hopper, & – 28 / 41 – Rathnasiri, 2004). In public sector organisations and NGOs, management accounting figures can inform on the same issues and service quality (Abernethy & Stoelwinder, 1991; Black et al., 2001; Forgione & Giroux, 1989; Johnson, 1994; Lawrence & Sharma, 2002; Modell, 2003; Parker & Guthrie, 2005; Pettersen, 1995; Unerman & O'Dwyer, 2006b). In all these cases, managers are demanding information contributing to their own evidence giving of value creation for the Higher-Stakeholder. As the latter is unbeknown, no one can argue that He actually requires such figures. Management accounting is a practice per se, insofar as it creates routines re the nature of figures given, procedures and formats to record and report them (Ahrens & Chapman, 2002, 2007; Ahrens & Mollona, 2007; Jørgensen & Messner, 2009). This is where non-profits’ managers enter into an accountability relationship with their volunteers and employees. As any other organisation accountable to its funders and clients (customers or beneficiaries), members in a non-profit are expected to conduct operations in a certain way and achieve certain results that justify resources’ entrusting (Anthony & Herzlinger, 1975). As in any other organisation, and especially owing to the imperative to account for the righteous use of funds (effective use for the purpose for which they were donated), programme managers follow up the resources they are entrusted and the way they spend them in a more or less sophisticated day-today management accounting system (Anthony & Young, 1994; Young, 1994). The official management accounting system records expenses in relation to the origin or resources but also what matters to the organisation. That is, internal controls and management accounting systems shall mostly follow up what is central to the effective conduct of operations. For instance, in a school run by a non-profit, what needs to be accounted for shall be learning material such as books, notebooks, pens, blackboards, desks and chairs, etc. (Khadaroo, 2008); in a football club, it would be balls, clothes, shoes, infirmary material in case of injury, etc. (Carlsson-Wall et al., 2017); in an art gallery, it would be artworks exhibited, artworks inventoried or artworks loaned, etc. (Christensen & Mohr, 1995, 1999). Re people’s day conduct aimed at executing the non-profit’s mission, the main challenge is that it is very difficult to control volunteers and demand them an account of their conduct. On many occasions, especially when volunteers join because of the non-profit’s advocacy or because they are just benevolent, willing to help, there is always a risk of misunderstanding and rejection (Joannidès, 2012; Pullen & Rhodes, 2013; Shapiro & Matson, 2008). However, non-profits’ managers are confronted with the imperative of controlling that volunteers too contribute to the organisation’s overall mission and behave themselves in a convergent manner. Therefore, not exactly the same controls can apply to those as to those who are salaried for the same type of occupation (O'Brien & Tooley, 2013). Whilst formal and explicit controls can apply to employees without major protests more informal controls seem to be applicable to volunteers, almost taking on a ludic form (Hardy & Ballis, 2013). Volunteers would not easily accept to be asked too many explicit questions re their personal involvement and achievements as a traditional performance meeting would suggest; formal meetings tend to be perceived as managerial exercise of disciplinary power over them (Roberts et al., 2006). Case n°8. A social work non-profit Informal internal controls Manager’s office, Paris Cœur de Vey, Every Thursday, 2005-2007, 8:00pm Once a week, active volunteers in a local non-profit doing grassroots social work tell managers the story of their involvement. They comment on their activities, achievements, doubts and expectations in a relatively relaxed environment. Volunteer supposedly fairly report on these to their manager, the relationship between them resting upon mutual trust. – 29 / 41 – The manager: ‘So, what did you do this week?’ The volunteer: ‘Well, I participated in some of scheduled activities, as you know. On Wednesday, I supervised for two hours the homework of a teenager.’ The manager: ‘What topics? The minister asks. The volunteer: ‘This week, we prepared an examination in Russian and in English. We also made several math exercises on the Thales theorem.’ Meanwhile, the manager’s PA wrote in a book of accounts exactly what the volunteer was saying. Here, the manager asks informal questions the volunteer answers under a format seemingly understood by both. Indeed, the minister systematically poses what questions to have clarifications and specifications re recent conduct. On the other hand, the volunteer provides so answers, in which he gives details directed at fulfilling the manager’s informal requirements. Ultimately, when no more questions on the clarity of answers need to be asked, the conversation ends. In the mean time, a scribe records in a book of accounts all these declarations, which come to appraise the consistency of individual conduct with organisation overall mission. The procession in such discursive and scribing practices are made systematic and routinised, manager status and office making the event formal and procedural. Conclusion It appears in this chapter that management control and accounting in non-profits is very specific and cannot be the mere application of what is at work in private companies or in the public sector. What differentiates non-profits from the private sector is the relation to money at the levels of expenses and resources. Resources are central, since they are the condition of possibility for mission execution; resources are not an end per se. Unlike the private sector, expenses are a concern, not because of the amounts of money that are managed, but because they must be used for the purpose for which they are donated. This implies that management accounting in nonprofits is aimed at matching resource origin with destination and effective use. Management control systems more broadly find themselves strongly tied to the discharging of accountability to donors and other stakeholders. The first difference from management control systems in private companies certainly lies in the ultimate purpose: facilitating the discharging of accountability and not just upholding managerial decision-making. Non-profits also differ from the public sector insofar as they are not as directly confronted with the constraints imposed by the pubic interest and democracy on managers. Acting as surrogates for public authorities, non-profits bear constraints of a similar to those of sub-contractors fully integrated in the value chain. Therefore, when running public policy programmes, non-profits are directly controlled from the public sector. Owing to non-profits’ peculiarities, controls cannot merely focus on value (for money) or on outputs (results and achievements). These fall within the span of control but are just a part thereof, as the two pyramids developed in figure 4.1 and 4.2 reveal: management control in non-profits, under the purview of facilitating the discharging of accountability intertwines behaviour control, norms and standards, values and beliefs, and outputs. This intertwining is revelatory of the ideology spread by a non-profit, resulting in controls being mutual, as summarised through the Reversed Panopticon. Bibliography Abernethy, M. A., & Stoelwinder, J. U. (1991). Budget use, task uncertainty, system goal orientation and subunit performance: A test of the `fit' hypothesis in not-for-profit hospitals. – 30 / 41 – Accounting, Organizations and Society, 16(2), 105-120. Abernethy, M. A., & Stoelwinder, J. U. (1995). The role of professional control in the management of complex organizations. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(1), 1-17. Abrahamson, E. (1997). The emergence and prevalence of employee management rhetorics: the effects of long waves, labor unions and turnovers, 1875 to 1992. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 491-533. Adam, A., & Shavit, T. (2008). How Can a Ratings-based Method for Assessing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Provide an Incentive to Firms Excluded from Socially Responsible Investment Indices to Invest in CSR? Journal of Business Ethics, 82, 899-905. Aggarwal, R. K., Evans, M. E., & Nanda, D. (2012). Nonprofit boards: Size, performance and managerial incentives. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 53(1), 466-487. Agócs, C. (1997). Institutionalized Resistance to Organizational Change: Denial, Inaction and Repression. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(9), 917-931. Ahrens, T., & Chapman, C. S. (2002). The structuration of legitimate performance measures and management: day-to-day contests of accountability in a U.K. restaurant chain. Management Accounting Research, 13(2), 151-171. Ahrens, T., & Chapman, C. S. (2007). Management accounting as practice. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(1-2), 1-27. Ahrens, T., & Mollona, M. (2007). Organisational control as cultural practice--A shop floor ethnography of a Sheffield steel mill. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(4-5), 305-331. Al Arabi, F. (2017). Islamic financial products and services in Western banks - Whence and whither? Doctorate of Business Administration, Grenoble École de Management, Grenoble. Anderson, H., Welsh, M., Ramsay, I., & Gahan, P. (2012). THE EVOLUTION OF SHAREHOLDER AND CREDITOR PROTECTION IN AUSTRALIA: AN INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON. The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 61(1), 171-207. Anheier, H., & Salamon, L. (1994). The emerging sector: the nonprofit sector in comparative perspective. An overview. Baltimore: The John Hopkins Sector Series. Anheier, H., & Salamon, L. (1996). The emerging nonprofit sector: an overview. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Anheier, H., & Salamon, L. (1997). Defining the emerging sector: a cross-national analysis. Baltimore: The John Hopkins Sector Series. Anthony, R., & Young, D. W. (1994). Accounting and financial management. In R. D. Herman (Ed.), The Jossey-Bass handkook of nonprofit leadership and management (pp. 403-443). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Anthony, R. N., Dearden, J., & Bedford, N. M. (1984). Management Control Systems. Homewood: Il: Irwin. Anthony, R. N., & Herzlinger, M. (1975). Management Control in nonprofit organizations. Homewood: Richard D Irwind Inc. (ed). Anthony, R. N., & Young, D. W. (1984). Management Control in nonprofit organizations. Homewood: Irwin Inc. Armour, J., Deakin, S., Lele, P., & Siems, M. (2009). How Do Legal Rules Evolve? Evidence from a Cross-Country Comparison of Shareholder, Creditor, and Worker Protection. The American Journal of Comparative Law, 57(3), 579-629. Armstrong, P. (1994). The Influence of Michel Foucault on Accounting Research. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 5(1), 25-55. Armstrong, P. (2002). The cost of activity-based management. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 27(1-2), 99-120. Avshalom, A., & Rachman-Moore, D. (2004). The Methods Used to Implement an Ethical Code of Conduct and Employee Attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 54(3), 225-244. Backhof, J. F., & Martin, C. L. J. (1991). Historical perspectives: development of the codes of ethics – 31 / 41 – in legal, medical and accounting professions. Journal of Business Ethics, 10, 99-110. Badiou, A. (2001). Ethics: an essay on the understanding of Evil. London: Verso. Badiou, A. (2008). The Communist hypothesis. New Left Review, 49, 29-42. Badiou, A. (2009). Theory of the subject. London: Continuum. Badiou, A. (2012a). Philosophy for militants (Pocket communism). London: Verso. Badiou, A. (2012b). The rebirth of history. London: Verso. Ballou, B., & King, R. S. (1999). Olympic soccer comes to Birmingham: managing a nonprofit organization's accounting and finance in a public setting. Journal of Accounting Education, 17(4), 443-472. Behling, F. (2018). Welfare Beyond the Welfare State: The Employment Relationship in Britain and Germany. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Benito, B., Montesinos, V., & Bastida, F. (2008). An example of creative accounting in public sector: The private financing of infrastructures in Spain. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19(7), 963-986. Bhimani, A., & Soonawalla, K. (2005). From conformance to performance: The corporate responsibilities continuum. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 24(3), 165-174. Black, S., Briggs, S., & Keogh, W. (2001). Service quality performance measurement in public/private sectors. Managerial Auditing Journal, 16(7), 400 - 405. Block, F. (2013). Relational Work and the Law: Recapturing the Legal Realist Critique of Market Fundamentalism. Journal of Law and Society, 40(1), 27-48. Boon, A., Flood, J., & Webb, J. (2005). Postmodern Professions? The Fragmentation of Legal Education and the Legal Profession. Journal of Law and Society, 32(3), 473-492. Bou-Chabké, S. (2016). TBC…. DBA, Grenoble École de Management, Grenoble. Boyce, G. (2004). Critical accounting education: teaching and learning outside the circle. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15(4-5), 565-586. Brivot, M., & Gendron, Y. (2011). Beyond panopticism: On the ramifications of surveillance in a contemporary professional setting. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 36(3), 135-155. Broadbent, J., Dietrich, M., & Laughlin, R. (1996). The development of principal-agent, contracting and accountability relationships in the public sector: conceptual and cultural problems. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 7(3), 259-284. Broadbent, J., Gill, J., & Laughlin, R. (2008). Identifying and controlling risk: The problem of uncertainty in the private finance initiative in the UK's National Health Service. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19(1), 40-78. Broadbent, J., & Laughlin, R. (2003). Public private partnerships: an introduction. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 16(3), 332 - 341. Brooks, L. J. (1989). Ethical code of conduct: deficient in guidance for the Canadian accounting profession. Journal of Business Ethics, 71, 117-129. Brown, E., & Caughlin, K. (2009). Donors, ideologues, and bureaucrats: government objectives and the performance of the nonprofit sector. Financial Accountability & Management, 25(1), 99-114. Cadge, W., & Wuthnow, R. (2006). Religion and the nonprofit sector. In W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The nonprofit sector – a research handbook (pp. 485-505). Beverly Hills: Yale University Press. Cardenas, S. (2011). Conflict and Compliance: State Responses to International Human Rights Pressure: University of Pennsylvania Press. Carlisle, Y. M., & Manning, D. J. (1996). The Domain of Professional Business Ethics. Organization, 3(3), 341-360. Carlsson-Wall, M., Kraus, K., & Karlson, L. (2017). Management control in pulsating organisations—A multiple case study of popular culture event. Management Accounting Research, 35(6), 20-34. Cast, A. D., Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (1999). Does the Self Conform to the Views of Others? Social – 32 / 41 – Psychology Quarterly, 62(1), 68-82. Chartier, G. (2012). Enforcing law and being a State. Law and Philosophy, 31(1), 99-123. Chauvey, J.-N., Naro, G., & Seignour, A. (2015). Rhétorique et mythe de la Performance Globale L’analyse des discours de la Global Reporting Initiative. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 33, 79-91. Christensen, A. L., & Mohr, R. M. (1995). Testing a positive theory model of museum accounting practices. Financial Accountability & Management, 11(4), 317-335. Christensen, A. L., & Mohr, R. M. (1999). Nonprofit Lobbying: Museums and Collections Capitalization. Financial Accountability & Management, 15(2), 115-133. Christensen, A. L., & Mohr, R. M. (2003). Not-for-Profit Annual Reports: What do Museum Managers Communicate? Financial Accountability & Management, 19(2), 139-158. Clark, L., & Roberts, S., J. (2010). Employers' use of social networking sites. a socially irresponsible practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 507-525. Clemens, E., S. (2006). The constitution of citizens: political theories of nonprofit organizations. In W. W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The nonprofit sector – A research handbook (pp. 207-220). New Haven: Yale University Press. Collier, P. M. (2005). Governance and the quasi-public organization: a case study of social housing. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 16(7), 929-949. Connolly, C., & Hyndman, N. (2000). Charity accounting: an empirical analysis of the impact of recent changes. The British Accounting Review, 32(1), 77-100. Connolly, C., & Hyndman, N. (2001). A Comparative Study on the Impact of Revised SORP 2 on British and Irish Charities. Financial Accountability & Management, 17(1), 73-97. Connolly, C., & Hyndman, N. (2004). Performance reporting: a comparative study of British and Irish charities. The British Accounting Review, 36(2), 127-154. Cordery, C., Baskerville, R. F., & Porter, B. (2011). Not reporting a profit: constructing a nonprofit organisation. Financial Accountability & Management, 27(4), 363-384. Cowton, C. J., & Dopson, S. (2002). Foucault's prison? Management control in an automotive distributor. Management Accounting Research, 13(2), 191-213. Cragg, W. (2000). Human rights and business ethics: fashioning a new social contract. Journal of Business Ethics, 27, 205-214. Crettez, B., Deffains, B., & Musy, O. (2014). Legal convergence and endogenous preferences. International Review of Law and Economics, 39(0), 20-27. Davison, J. (2011). Barthesian perspectives on accounting communication and visual images of professional accountancy. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 24(2), 250-283. de Haas, M., & Algera, J. A. (2002). Demonstrating the effect of the participative dialogue: participation in designing the management control system. Management Accounting Research, 13(1), 41-69. del Carmen Triana, M., Wagstaff, M. F., & Kim, K. (2012). That’s Not Fair! How Personal Value for Diversity Influences Reactions to the Perceived Discriminatory Treatment of Minorities. Journal of Business Ethics, 111, 211-218. Derrida, J., & Wieviorka, M. (2001). Foi et savoir. Paris: Seuil. Deshpande, S. P. (1996). Ethical climate and the link between success and ethical behavior: An empirical investigation of a non-profit organization. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(3), 315320. Dillenburg, S., Greene, T., & Erekson, H. (2003). Approaching Socially Responsible Investment with a Comprehensive Ratings Scheme: Total Social Impact. Journal of Business Ethics, 43, 163-177. DiMaggio, P. (2006). Nonprofit organizations and the intersectoral division of labor in the Arts. In W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The nonprofit sector – a research handbook (pp. 432-461). Beverly Hills: Yale University Press. Dorf, M. D. (2006). Problem-solving courts and the judicial accountabiltiy deficit. In M. W. Dowdle – 33 / 41 – (Ed.), Public accountability – Designs, dilemmas and experiences (pp. 301-328). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ee, C. (2011). Compliance by Design: IT controls that work: IT Governance Ltd. Eldenburg, L., & Krishnan, R. (2003). Public versus private governance: a study of incentives and operational performance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 35(3), 377-404. Esping-Andersen, G. (1992). The three worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Esping-Andersen, G. (1996). Welfare States in Transition: National Adaptations in Global Economies. London: Sage publications. Ezzamel, M., & Willmott, H. (1993). Corporate governance and financial accountability in the UK public sector. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 6(3), 109-132. Fasterling, B. (2012). Development of Norms Through Compliance Disclosure. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(1), 73-87. Feinberg, K. R. (2006). What Is Life Worth?: The Inside Story of the 9/11 Fund and Its Effort to Compensate the Victims of September 11th: The Unprecedented Effort to Compensate the Victims of 9/11. New York: Public Affairs. Feldner, S. (2006). Living our mission: A study of university mission building. Communication Studies, 67-85. Ferris, G. R., & King, T. R. (1992). The politics of age discrimination in organizations. [journal article]. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(5), 341-350. Fiol, M. (1991). Les modes de convergence des buts dans les organisations. Doctorat d'Etat, Université Paris Dauphine, Paris. Firmin, M. W., & Gilson, K. M. (2010). Living our mission: A study of university mission building. Higher Christian Education, 9, 60-70. Fisher, J., Gunz, S., & McCutcheon, J. (2001). Private/Public Interest and the Enforcement of a Code of Professional Conduct. Journal of Business Ethics, 31, 191-207. Forgione, D., & Giroux, G. (1989). Fund accounting in nonprofit hospitals: a lobbying perspective. Financial Accountability & Management, 5(4), 233-244. Forneret, M. (2013). Pulling the trigger: an analysis of circuit court review of the "Prosecutor Bar". Columbia Law Review, 113(4), 1007-1050. Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and Punish. New York: Vintage Books. Foucault, M. (1984). History of sexuality: 3. The care of the self. New York: Vintage Books. Frankel, M. S. (1989). Professional codes: why, how and with what impact? Journal of Business Ethics, 8, 109-115. Freeman, J. (2006). Extending public accountability through privatization: from public law to publicization. In M. W. Dowdle (Ed.), Public accountability – Designs, dilemmas and experiences (pp. 83-111). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Frickey, P. P. (2005). Getting from Joe to Gene (McCarthy): The Avoidance Canon, Legal Process Theory, and Narrowing Statutory Interpretation in the Early Warren Court. California Law Review, 93(2), 397-464. Froud, J. (2003). The Private Finance Initiative: risk, uncertainty and the state. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(6), 567-589. Furneaux, C., & Ryan, N. (2015). Nonprofit service delivery for government: accountability relationships and mechanisms. In Z. Hoque & L. Parker (Eds.), Performance management in nonprofit organizations: global perspectives (pp. 185-210). London: Routledge. Gaumnitz, R. B., & Lere, C. J. (2002). Contents of codes of ethics of professional business organizations in the United States. Journal of Business Ethics, 35, 35-49. Gautier, A., & Pache, A.-C. (2015). Research on Corporate Philanthropy: A Review and Assessment. [journal article]. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(3), 343-369. Gilliland, D. I., & Manning, K. C. (2002). When Do Firms Conform to Regulatory Control? The Effect of Control Processes on Compliance and Opportunism. Journal of Public Policy & – 34 / 41 – Marketing, 21(2), 319-331. Goddard, A., & Assad, M. J. (2006). Accounting and navigating legitimacy in Tanzanian NGOs. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 19(3), 377 - 404. Goldner, L. (2018). Revolution, Defeat and Theoretical Underdevelopment Russia, Turkey, Spain, Bolivia. London: Haymarket Books. Gray, R., Bebbington, J., & Collison, D. (2006). NGOs, civil society and accountability: making the people accountable to capital. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 19(3), 319 - 348. Gray, R., & Gray, S. J. (2011). Accountability and Human rights: a tentative exploration and a commentary. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 22(8), 781-789. Greenberg, M. D. (2010). Directors as Guardians of Compliance and Ethics Within the Corporate Citadel: What the Policy Community Should Know: RAND Corporation. Grimsey, D., & Lewis, M. K. (2005). Are Public Private Partnerships value for money?: Evaluating alternative approaches and comparing academic and practitioner views. Accounting Forum, 29(4), 345-378. Gumbrell-McCormick, R., & Hyman, R. (2013). Trade Unions in Western Europe: Hard Times, Hard Choices. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Haegele, K. (2012). White Elephants : On Yard Sales, Relationships, and Finding What Was Missing. London: Microcosm Publishing. Hainsworth, P. (2008). The Extreme Right in Western Europe. London: Routledge. Hall, A. (2008). Scandal Sensation Social Democracy: The SPD Press and Wilhelmine Germany 1890-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hanlon, G. (2010). Knowledge, risk and Beck: Misconceptions of expertise and risk. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 21(3), 211-220. Harcourt, S., & Harcourt, M. (2002). Do Employers Comply with Civil/Human Rights Legislation? New Evidence from New Zealand Job Application Forms. Journal of Business Ethics, 35, 207-221. Hardy, L., & Ballis, H. (2013). Accountability and giving accounts: Informal reporting practices in a religious corporation. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 26(4), 539-566. Havens, J. J., O'Herlihy, M. A., & Schervish, P. (2006). Charitable giving: how much, by whom, to what and how? In W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The nonprofit sector – A research handbook (pp. 542-567). Yale: Yale University Press. Herman, R. D. (2009). Are Public Service Nonprofit Boards Meeting Their Responsibilities? Public Administration Review, 69(3), 387-390. Holmwood, J., & O'Toole, T. (2017). Countering Extremism in British Schools? London: Policy Press. Hopper, T., & Armstrong, P. (1991). Cost accounting, controlling labour and the rise of conglomerates. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 16(5-6), 405-438. Hoque, Z. (2003). Total Quality Management and the Balanced Scorecard approach: a critical analysis of their potential relationships and directions for research. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 14(5), 553-566. Humphrey, C., Miller, P., & Scapens, B. (1993). Accountability and accountable management in the UK public sector. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 6(3), 7-29. Hyndman, N., & McDonnell, P. (2009). Governance and charities: an exploration of key themes and the development of a research agenda. Financial Accountability & Management, 25(1), 531. Irvine, H. (1999). Who's counting? An institutional analysis of expectations of accounting in a nonprofit religious/charitable organization within a changing environment. Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Wollongong. Irvine, H. (2002). The legitimizing power of financial statements in The Salvation Army in England, 1865 - 1892. Accounting Historians Journal, 29(1), 1-36. Irvine, H. (2005). Balancing money and mission in a local church budget. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 18(2), 211-237. – 35 / 41 – Ittner, C. D., & Larcker, D. F. (1997). Quality strategy, strategic control systems and organizational performance. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 22(3/4), 293-314. Jayasinghe, K., & Wickramasinghe, D. (2006). Can NGOs deliver accountability? Predictions, realities and difficulties. In M. Abdel-Kader (Ed.), NGOs: Roles and Accountability: Introduction (pp. 296-327). Delhi: ICFAI (Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts India). Jenkins, J. C. (2006). Nonprofit organizations and political advocacy. In W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The nonprofit sector – A research handbook (pp. 307-332). Yale: Yale University Press. Joannidès, V. (2009). Accountability and ethnicity in a religious setting: the Salvation Army in France, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and Sweden. PhD Unpubllished PhD dissertation, Université Paris Dauphine, Paris. Joannidès, V. (2012). Accounterability and the problematics of accountability. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 23(3), 244-257. Joannidès, V., Démettre, C., & Naudin, J. (2008). Le risque: un outil de contrôle? Management & Sciences Sociales, 5, 179-196. Joannidès, V., Jaumier, S., & Hoque, Z. (2015). Patterns of boardroom discussions around the accountability process in a nonprofit organisation. In Z. Hoque & L. D. Parker (Eds.), Performance management in nonprofit organizations – Global perspectives (pp. 234-259). London: Routledge. Joannidès, V., Jaumier, S., & Le Loarne, S. (2013). La fabrique du contrôle: une ethnométhodologie du choix des outils de gestion. Comptabilité Contrôle Audit, 19(3), 87-116. Joannidès, V., & McKernan, J. (2015). Ethics: from negative regulations to fidelity to the event. In P. O'Sullivan, N. Allington & M. Esposito (Eds.), The philosophy, politics and economics of finance in the 21st century – From hubris to disgrace (pp. 310-331). London: Routledge. Johnson, H. T. (1994). Relevance Regained: Total Quality Management and the Role of Management Accounting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 5(3), 259-267. Jørgensen, B., & Messner, M. (2009). Accounting and strategising: a case study from new product development. Accounting, Organizations & Society, in press. Jupe, R. (2009). A "fresh start" of the "worst of all words"? A critical financial analysis of the performance and regulation of Network Rail in Britain's privatised railway system. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 20(2), 175-204. Kelly, K. S. (2012). Effective fundraising. London: Routledge. Kendall, J., Knapp, M., & Forder, J. (2006). Social care and the nonprofit sector in the Western developed world. In W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The nonprofit sector – a research handbook (pp. 415-431). Beverly Hills: Yale University Press. Kennedy, F. A., Burney, L. L., Troyer, J. L., & Caleb Stroup, J. (2010). Do non-profit hospitals provide more charity care when faced with a mandatory minimum standard? Evidence from Texas. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 29(3), 242-258. Khadaroo, I. (2008). The actual evaluation of school PFI bids for value for money in the UK public sector. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19(8), 1321-1345. Knechel, W. R. (2007). The business risk audit: Origins, obstacles and opportunities. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(4‚Äì5), 383-408. Latin, H. A., Tannehill, G. W., & White, R. E. (1976). Remote Sensing Evidence and Environmental Law. California Law Review, 64(6), 1300-1446. Laughlin, R. (1996). Principals and higher-principals: accounting for accountability in the caring professions. In R. Munro & J. Mouritsen (Eds.), Accountability: Power, ethos and the technologies of managing (pp. 225-244). London: International Thomson Business Press. Lawrence, S., & Sharma, U. (2002). Commodification of Education and Academic LABOUR-Using the Balanced Scorecard in a University Setting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 13(56), 661-677. Leavitt, N., & Maykuth, P. L. (1989). Conformance to Attorney Performance Standards: Advocacy Behavior in a Maximum Security Prison Hospital. Law and Human Behavior, 13(2), 217-230. – 36 / 41 – Lehman, G. (2007). The accountability of NGOs in civil society and its public spheres. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 18(6), 645-669. Light, P. C. (2000). Making nonprofits work: A report on the tides of nonprofit management reform: Brookings Institution Press. Light, P. C. (2004). Sustaining nonprofit performance: The case for capacity building and the evidence to support it: Brookings Institution Press. Lightbody, M. (2000). Storing and shielding: financial management behaviour in a church organization. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 13(2), 156-174. Lightbody, M. (2003). On Being a Financial Manager in a Church Organisation: Understanding the Experience. Financial Accountability & Management, 19(2), 117-138. Liket, K., & Simaens, A. (2015). Battling the Devolution in the Research on Corporate Philanthropy. [journal article]. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(2), 285-308. Liu, H., & Baker, C. (2016). Ordinary Aristocrats: The Discursive Construction of Philanthropists as Ethical Leaders. [journal article]. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(2), 261-277. Luidens, D. A. (1982). Bureaucratic control in a Protestant denomination. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 21(2), 163-175. Macduff, N. (1994). Principles of training for volunteers and employees. In R. D. Herman (Ed.), The Jossey-Bass handkook of nonprofit leadership and management (pp. 591-615). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Madry, A. R. (2005). Global Concepts, Local Rules, Practices of Adjudication and Ronald Dworkin's Law as Integrity. Law and Philosophy, 24(3), 211-238. Mammone, A., Godin, E., & Jenkins, B. (Eds.). (2012). Mapping the Extreme Right in Contemporary Europe: From Local to Transnational. London: Routledge. Martin, P., & Kleinfelder, R. (2008). Lions Club in the 21st century. London: AuthorHouse. Martínez, C. V. (2003). Social Alliance for Fundraising: How Spanish Nonprofits Are Hedging the Risks. [journal article]. Journal of Business Ethics, 47(3), 209-222. McGillis, D. (1978). Attribution and the Law: Convergences between Legal and Psychological Concepts. Law and Human Behavior, 2(4), 289-300. McKendall, K., DeMarr, B., & Jones-Rikkers, C. (2002). Ethical Compliance Programs and Corporate Illegality: Testing the Assumptions of the Corporate Sentencing Guidelines. Journal of Business Ethics, 37(4), 367-383. McKernan, J. F. (2012). Accountability as aporia, testimony and gift. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 23(3), 258-278. McKernan, J. F., & Kosmala, K. (2004). Accounting, love and justice. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 17(3), 327-360. McKernan, J. F., & Kosmala, K. (2007). Doing the truth: religion deconstruction justice, and accounting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20(5), 729-764. McKernan, J. F., & McPhail, K. (2012). Accountability and accounterability. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, in press. McKinlay, A., & Pezet, E. (2010). Accounting for Foucault. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 21(6), 486-495. McPhail, K., & McKernan, J. (2011). Accounting for human rights: An overview and introduction. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 22(8), 733-737. Mehrpouya, A., & Samiolo, R. (2016). Performance measurement in global governance: Ranking and the politics of variability. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 55, 12-31. Mikes, A. (2009). Risk management and calculative cultures. Management Accounting Research, 20(1), 18-40. Mintzberg, H. (1999). Ideology and the missionary organization. The Strategy Process In H. Mintzberg, J. B. Quinn & S. Ghosal (Eds.). London: Prentice Hall. Modell, S. (2003). Goals versus institutions: the development of performance measurement in the Swedish university sector. Management Accounting Research, 14(4), 333-359. – 37 / 41 – Moore, D. H. (2010). Do US Courts discriminate agaisnt treaties? Equivalence, duality and nonself-execution. Columbia Law Review, 110(8), 2228-2294. Morgan, B. (2006). Technocratic vs. convivial accountability. In M. W. Dowdle (Ed.), Public accountability – Designs, dilemmas and experiences (pp. 243-268). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ng, E. S., & Metz, I. (2015). Multiculturalism as a Strategy for National Competitiveness: The Case for Canada and Australia. [journal article]. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(2), 253-266. Niblett, A., Posner, R. A., & Shleifer, A. (2010). The Evolution of a Legal Rule. The Journal of Legal Studies, 39(2), 325-358. O'Brien, E., & Tooley, S. (2013). Accounting for volunteer services : a deficiency in accountability. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 10(3/4), 279-294. O'Dwyer, B., & Unerman, J. (2007). From functional to social accountability: Transforming the accountability relationship between funders and non-governmental development organisations. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20(3), 446-471. Ogden, S. G., & Bougen, P. (1985). A radical perspective on the disclosure of accounting information to trade unions. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 10(2), 211-224. Ouchi, W. G. (1979). A Conceptual Framework for the Design of Organizational Control Mechanisms. Management Science, 25(9), 833-848. Ouchi, W. G. (1980). Markets, Bureaucracies and Clans. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(1), 129141. Owens, R. J., & Wedeking, J. P. (2011). Justices and Legal Clarity: Analyzing the Complexity of U.S. Supreme Court Opinions. Law & Society Review, 45(4), 1027-1061. Parker, C. (2000). The Ethics of Advising on Regulatory Compliance: Autonomy or Interdependence? Journal of Business Ethics, 28(4), 339-351. Parker, L. D., & Guthrie, J. (2005). Welcome to "the rough and tumble": Managing accounting research in a corporatised university world. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 18(1), 5 - 13. Parsons, T., & Platt, G. M. (1973). The American university. Boston: Harvard University Press. Pawson, B., & Joannidès, V. (2015). What costs accountability? Financial accountability, mission and fundraising in nonprofits. In Z. Hoque & L. Parker (Eds.), Performance management in nonprofit organizations: global perspectives (pp. 211-233). London: Emerald. Pettersen, I. J. (1995). Budgetary control of hospitals – ritual rhetorics and rationalised myths? Financial Accountability & Management, 11, 207-221. Plowright, A. (2017). The French Exception: Emmanuel Macron – The Extraordinary Rise and Risk. London: Icon Books Ltd. Pomper, G. M. (1992). Passions and Interests: Political Party Concepts of American Democracy. Topeka: University Press of Kansas. Pullen, A., & Rhodes, C. (2013). Corporeal ethics and the politics of resistance in organizations. Organization. Quattrone, P. (2009). Books to be practiced: Memory, the power of the visual, and the success of accounting. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 34(1), 85-118. Rai, L. (1975). Pressures to Conform. Economic and Political Weekly, 10(1/2), 16-18. Rathgeb-Smith, S., & Grønberg, K. A. (2006). Scope and theory of government-nonprofit relations. In W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The nonprofit secteor – A research handbook (pp. 221-242). Yale: Yale University Press. Ritchie, W. J., Anthony, W. P., & Rubens, A. J. (2004). Individual Executive Characteristics: Explaining the Divergence Between Perceptual and Financial Measures in Nonprofit Organizations. [journal article]. Journal of Business Ethics, 53(3), 267-281. Roberts, J., Sanderson, P., Barker, R., & Hendry, J. (2006). In the mirror of the market: The disciplinary effects of company/fund manager meetings. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(3), 277-294. – 38 / 41 – Robson, K., Willmott, H., Cooper, D., & Puxty, T. (1994). The ideology of professional regulation and the markets for accounting labour: Three episodes in the recent history of the U.K. accountancy profession. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 19(6), 527-553. Rodrigues, L. c. L., & Craig, R. (2009). Teachers as servants of state ideology: Sousa and Sales, Portuguese School of Commerce, 1759-1784. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 20(3), 379398. Roehling, M. V. (2002). Weight Discrimination in the American Workplace: Ethical Issues and Analysis. [journal article]. Journal of Business Ethics, 40(2), 177-189. Rothschild-Whitt, J. (1979). The Collectivist Organization: An Alternative to Rational-Bureaucratic Models. American Journal of Sociology, 44(4), 509-527. Rouse, J., Davis, J., & Friedlob, T. (1986). The relevant experience criterion for accounting accreditation by the AACSB —A current assessment. Journal of Accounting Education, 4(1), 147-160. Rupert, J., Jehn, K. A., Engen, M. L. v., & Reuver, R. S. M. d. (2010). Commitment of Cultural Minorities in Organizations: Effects of Leadership and Pressure to Conform. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(1), 25-37. Sajay, S., Covaleski, M., & Dirsmith, M. W. (2009). Accounting in and for US Governments and Non-profit Organizations: a Review of Research and a Call to Further Inquiry. In C. Chapman, A. Hopwood & M. D. Shields (Eds.), Handbook of Management Accounting Research (Vol. 3, pp. 1299-1322). Salvation-Army. (2010). The Salvation Army responds to Haity earthquake, frofile://localhost/m%20http/::www.salvationarmy.org:ihq:news:3BA710B2E3E570788 02576AA004D0ED3 Samuel, S., Covaleski, M. A., & Dirsmith, M. W. (2009). Accounting in and for US Governments and Non-profit Organizations: a Review of Research and a Call to Further Inquiry. In C. S. Chapman, A. G. Hopwood & M. D. Shields (Eds.), Handbooks of Management Accounting Research (Vol. 3, pp. 1299-1322): Elsevier. Sandron, F., & Hayford, S. R. (2002). Do Populations Conform to the Law of Anomalous Numbers? Population (English Edition, 2002-), 57(4/5), 755-761. Sansing, R., & Yetman, R. (2006). Governing private foundations using the tax law. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 41(3), 363-384. Sargeant, A. (1999). Charitable giving: Towards a model of donor behaviour. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(4), 215-238. Sargeant, A., & Shang, J. (1999). Fundraising principles and practice. London: John Willey & Sons. Schain, M. A., & Kesselman, M. (1998). A Century of Organized Labor in France: A Union Movement for the Twenty First Century? London: Palgrave Macmillan. Schatzki, T. R. (2000). Practice theory. In T. R. Schatzki, K. Knorr Cetina & E. Savigny (von) (Eds.), The practice turn in contemporary theory (pp. 1-14). London: Routledge. Schatzki, T. R. (2003). A new societist social ontology. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 33(2), 174-202. Schatzki, T. R. (2005). The sites of organizations. Organization Studies, 26(3), 465-484. Schlesinger, M., & Gray, B. (2006). Nonprofit organizations and healthcare: some paradoxes of persistent scrutiny. In W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The nonprofit sector – a research handbook (pp. 378-414). Beverly Hills: Yale University Press. Schultz, P. (2015). Analysing Phuket and the Boxing Day Tsunami. London: GRIN Publishing. Schwartz, M. (2005). Universal Moral Values for Corporate Codes of Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 59, 27-44. Shaoul, J. (2005). A critical financial analysis of the Private Finance Initiative: selecting a financing method or allocating economic wealth? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 16(4), 441-471. Shapiro, B., & Matson, D. (2008). Strategies of resistance to internal control regulation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(2-3), 199-228. Shirley, S., & Askiwith, R. (2013). Let it Go: The Story of the Entrepreneur Turned Ardent Philanthropist. – 39 / 41 – London: Andrews UK Limited. Sinclair, A. (1995). The chameleon of accountability: Forms and discourses. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(2-3), 219-237. Sobanjo-ter Meulen, A., Abramson, J., Mason, E., Rees, H., Schwalbe, N., Bergquist, S., & Klugman, K. P. (2015). Path to impact: A report from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation convening on maternal immunization in resource-limited settings; Berlin – January 29–30, 2015. Vaccine, 33(47), 6388-6395. Somers, M. J. (2001). Ethical Codes of Conduct and Organizational Context: A Study of the Relationship Between Codes of Conduct, Employee Behavior and Organizational Values. Journal of Business Ethics, 30, 185-195. Street, C. (2016). Gun Control: Guns in America, The Full Debate, More Guns Less Problems? No Guns No Problems? New York: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. Sturgeon, S. (1994). Finding and keeping the right employees. In R. D. Herman (Ed.), The JosseyBass handkook of nonprofit leadership and management (pp. 535-556). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Sud, M., VanSandt, C. V., & Baugous, A. M. (2009). Social Entrepreneurship: The Role of Institutions. [journal article]. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(1), 201-216. Taha, N. (2013). Forensic accounting applicability: the case of Lebanon. Doctorate of Business Administration DBA thesis, Grenoble École de Management, Grenoble. Thorpe, A. (2015). A history of the British Labour Party. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Tinker, T., & Fearfull, A. (2007). The workplace politics of U.S. accounting: Race, class and gender discrimination at Baruch College. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 18(1), 123-138. Tronconi, F. (2015). Beppe Grillo's Five Star Movement: Organisation, Communication and Ideology. London: Routledge. Tucker, S. (1962). Restitution: Quasi-Contract: Non-Conformance with State Building Contractors Licensing Statute as Basis for Denial of Restitution. Michigan Law Review, 60(6), 823-827. Unerman, J., & Bennett, M. (2004). Increased stakeholder dialogue and the internet: towards greater corporate accountability or reinforcing capitalist hegemony? Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(7), 685-707. Unerman, J., & O'Dwyer, B. (2006a). On James Bond and the importance of NGO accountability. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 19(3), 305 - 318. Unerman, J., & O'Dwyer, B. (2006b). Theorising accountability for NGO advocacy. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 19(3), 349 - 376. Unerman, J., & O'Dwyer, B. (2008). The Paradox of Greater NGO Accountability : A Case Study of Amnesty Ireland. Accounting, Organizations & Society, in press. Vaivio, J. (2006). The accounting of "The Meeting": Examining calculability within a "Fluid" local space. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(8), 735-762. Vamosi, T. (2005). Management accounting and accountability a new reality of everyday life. The British Accounting Review, 37, 443-470. van Tries, S., & Elshahat, M. F. (2007). The use of costing information in Egypt: a research note. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 3(3), 329 - 343. Vesterlund, L. (2006). Why do people give? In W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The nonprofit sector – a research handbook (pp. 568-589). Beverly Hills: Yale University Press. Weber, J., & Wasieleski, D. M. (2013). Corporate Ethics and Compliance Programs: A Report, Analysis and Critique. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(4), 609-626. Weber, M. (1922). Economy and Society. Berkeley: The University of California Press. Whelan, G., Moon, J., & Orlitzky, M. (2009). Human Rights, Transnational Corporations and Embedded Liberalism: What Chance Consensus? Journal of Business Ethics, 87(2), 367-383. White, W. H., Jr. (1995). Foreign Law, Politics & Litigants in U.S. Courts: A Discussion of Issues Raised by Transportes Aereos Nacionales, S. A. v. de Brenes. The University of Miami InterAmerican Law Review, 27(1), 161-202. – 40 / 41 – Wickramasinghe, D., Hopper, T., & Rathnasiri, C. (2004). Japanese cost management meets Sri Lankan politics: Disappearance and reappearance of bureaucratic management controls in a privatised utility. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 17(1), 85 - 120. Wright, S. (2011). PCI DSS: A Practical Guide to Implementing and Maintaining Compliance (3 ed.): IT Governance Ltd. Wu, G. (2015). China's Party Congress: Power, Legitimacy, and Institutional Manipulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wulfson, M. (2001). The Ethics of Corporate Social Responsibility and Philanthropic Ventures. Journal of Business Ethics, 29, 133-145. Yair, G. (2007). Existential Uncertainty and the Will to Conform: The Expressive Basis of Coleman's Rational Choice Paradigm. Sociology, 41(4), 681-698. Young, D. W. (1994). Management accounting. In R. D. Herman (Ed.), The Jossey-Bass handbook of nonprofit leadership and management (pp. 444-484). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Zetter, L. (2014). Lobbying: The Art of Political Persuasion. London: Harriman House Publishing. – 41 / 41 –