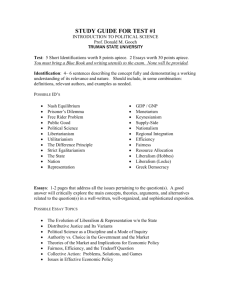

Reading for Lecture in WEEK 01 - HUMAN NATURE & Political Philosophy - Heywood

advertisement