Clinical Anatomy - 1991 - Beahrs - Gross anatomy in medicine

advertisement

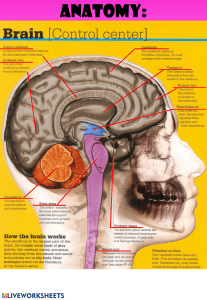

Clinical Anatomy 4:310-312 (1991) Oliver H. Beahrs EDITORIAL Gross Anatomy in Medicine Anatomy is the language of medicine because all of medicine relates to the human body and the function of its various parts and systems. Human anatomy is, in fact, one of the earliest sciences and traces its origin to the early Greek civilization. T h e Greek term for anatomy-anatome-means “taking apart.” T h e Latin t e r m d i s s e c a r t L i s for dissection. Anatomy in ancient times was expressed in sculpture and art. As knowledge of gross anatomy increased, it gave rise to many of the other basic sciences of medicine-pathology (morbid anatomy), embryology (developmental anatomy), histology and cytology (microscopic anatomy), physiology (functional anatomy), physical anthropology, and others. Furthermore, many of the terms used in medicine relating to the human body originated in anatomic parts and their function, such as anterior-posterior, palmar-plantar, proximal-distal, external-internal, abduction-adduction, elevation-depression, protraction-retraction, and others. Thus, anatomy must be considered the most basic science of medicine. I t forms the trunk of the tree from which all other medical sciences stem. As the body of knowledge increases, the branches spread in many directions and the tree grows. How then can a student of medicine not know anatomy and claim to understand the language of medicine, let alone the other sciences related to the human body? If a mechanic does not know the parts of the machine-automobile or television set-that h e is repairing it is unlikely that it will work in the end. So physicians, regardless of their specialty, must know and appreciate gross anatomy. Unfortunately, in the recent past, the explosion of medical knowledge has put pressure on the subjects within the medical curriculum, resulting in a decrease in emphasis on subjects whose current clinical applications were not appreciated. This resulted in a critical period for anatomy. So much so that a formal course in the subject was dropped from the curriculum, and anatomy then taught as part of the clinical subject-such as cardiac anatomy along with cardiology. It soon became apparent that the graduate from medical school was lacking in knowledge of this most basic subject of medicine. Now the pendulum is swinging back, and the importance of an in-depth study of anatomy is once again gaining importance in medical education. I t is difficult to understand why, irrespective of clinical specialty-surgery or psychiatry-a physician should not know the parts, the function, and the language of anatomy. Admittedly, to the young student, anatomy can be a “cold” subject requiring memorizing terminology. Without clinical implications, students can easily lose 0 1991 Wdey-Liss,Inc. l3ditorial 311 interest in the subject. It need not be so. An anatomy teacher can easily be innovative, creative, and make the subject interesting. However, gross anatomy to somc tcachcrs of anatomy has been a “chore” because they are unprepared and are trained in new fields of anatomy such as cellular biology. This, in part, led a group of interested physicians and scientists to form the American Association of Clinical Anatomists in 1983 to once again stimulate interest in teaching and clinical applications of human anatomy. To better understand anatomy, knowledge of embryology is essential. I t is best taught along with anatomy so the student understands the development of the human body. Also, from the clinical standpoint, especially in surgery, congenital abnormalities must be understood for successful treatment. An example of this is in cervical exploration for hyperparathyroidism. If parathyroid glands are not found in their usual positions, by knowing the avenue of descent of the glands in developmental anatomy and extending the surgical exploration appropriately, one can almost always find the glands in predictable ectopic positions. With this information in mind, expensive localizing tests are not necessary. T h e following are examples of how small bits of information are of value to the surgeon. In doing an operation in the pelvis requiring freeing the rectum, bleeding from the hollow of the sacrum is said to be a great hazard. However, considering that there are no collateral vessels between the presacral vessels and those of the rectum, bleeding from the dissection has to be considered iatrogenic. With knowledge of anatomy and using proper technique, bleeding can be prevented. If the surgeon knows the detailed anatomy of the facial nerve and its relationship to bony parts, parotidectomy becomes safe and the nerve easily dissected. Although gross anatomy should be known to all physicians, it is basic to a surgeon and the surgical specialty that h e practices. Surgeons should know the anatomy so thoroughly that at no time in the course of dissection should they have undue concern as to where specific structures are located or any question as to the identity of a structure. Lack of knowledge or hesitancy too often leads to disaster. T h e surgeon must be aware of anatomic variations, since this knowledge is crucial to the success of the operation. To learn basic anatomic information by trial and error at the expense of a patient undergoing an elective or emergency operation is morally wrong. Anatomy must be learned, first, with the aid of texts, by memorizing nomenclature and differentiating anatomic relationships. Second, the student must further study anatomy by dissecting cadavers in order to acquire an even greater understanding of the threedimensional inter-relationships of structures. Third, the surgical residents should supplement their detailed knowledge of live anatomy by assisting and learning from more experienced surgeons at the operating table. By the time residents are seniors or chiefs, they should not only be responsible surgeons, but experts in anatomy. From this time onward, an operation should be carried out in an organized manner, with dispatch and, in many respects, performed as “a song and a dance.” Certain technical aspects in handling tissues in the course of an operation must be recognized. Proper tension on tissues frequently will make them separate along tissue planes. Blunt dissection can, at times, be carried out more safely than sharp dissection. T h e use of traction and countertraction will not only facilitate separation of tissues, but along with pressure, aid in controlling bleeding. Major vessels should be ligated early so major blood loss will not occur. 312 Editorial Following resection of tissues in an operation, remaining structures in the anatomic site should be reconstructed in such a way as to re-establish anatomic relationships. In re-establishing bowel continuity after a resection, preferably an anastomosis should accurately approximate anatomic layers of the bowel wall. All techniques do not do this. With new imaging technology available in clinical practice, a detailed knowledge of anatomy becomes even more important. With computerized axial tomography ( C T scan), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound, cross-sectional anatomy must be known and anatomic relationships appreciated by the diagnostician as well as the surgeon. Endoscopic procedures require greater appreciation of anatomy viewed in a different perspective. T h e recent and rapid acceptance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy is an excellent example of how new technology is leading to a greater appreciation of anatomy. T h e need for detailed knowledge of anatomy has significantly increased over the past several decades. Intracardiac surgery 50 years ago first emphasized the need for understanding the detailed anatomy of the heart. Organ and tissue transplantation or transfer has increased the need for accurate knowledge of blood supply to tissues. Earlier surgical procedures required only information for excisional removal of tissues protecting blood supply to remaining structures. Microsurgery is being done today in the transfer of a section of small bowel to bridge a gap in the esophagus. To anastornose the alimentary tract parts, it is necessary to carefully join blood vessels to assure blood supply to them. A kidney transplant requires not only restoring blood supply to the kidney but also re-establishing urinary tract drainage. Coronary artery bypass or revascularization requires knowledge of arterial anatomy not previously needed. T h e approach to intracranial procedures is possible today because of imaging procedures to more clearly identify the lesions and anatomy involved. This permits operations not previously possible. Even ultrasound imaging has led to identification of congenital defects before birth, permitting repair of these by fetal surgery. Also, massive body defects caused by excisional removal of tumors or trauma can be reconstructed by transfer of tissue, resulting in restored function or repair of the cosmetic defect. T h e increasing technology and improvement of techniques of microsurgery will continue to make possible in the future surgical procedures not previously thought possible. These will require increased knowledge of detailed anatomy. Although the importance of gross anatomy in the medical curriculum waxes and wanes, it will always remain the most basic science in all of medicine. A few years ago, the interest in the subject was at a low point. However, in recent years, anatomy is regaining its rightful place in the medical curriculum and new technology and other advances in medicine are leading to added recognition of the importance of anatomy in the clinical practice of medicine. (Editor’s note: Dr. Beahrs served as first president of the Academy of Clinical Anatomy, and recent past president of the American College of Su7geons.) Oliver H. Beahrs Mayo C h i c Rochester, ,Minnesota 55905