Amstad, Marlene Sun, Guofeng Xiong, Wei - The Handbook of China's Financial System-Princeton University Press (2020)

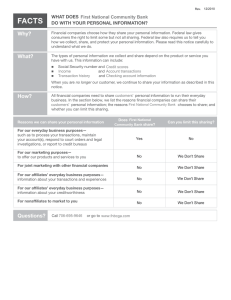

advertisement