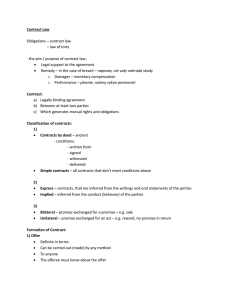

INTRODUCTION TO CONTRACT LAW. A Contract is defined by the Longman Law Dictionary to mean a legally binding agreement creating enforceable obligations. The Contract Act of Uganda 2010, laws of Uganda Section 10 defines a Contract as an agreement made with free consent of parties with capacity to contract, for lawful consideration and with a lawful object, with intention to be legally bound. The law of contract in Uganda, it is legally based on the English principles of the Law of contract and the contract Act 2010, Laws of Uganda. The law of contract governs Agreements which are intended to be legally binding. It allows parties to an agreement to make terms for themselves provided they do so within the limits of the law of the land/Uganda once private persons have made a binding contract the state will protect their legal interests by protecting the contract e.g A person can sue in the High Court Civil Division for breach of contract and court will award Damages or relevant remedy in accordance with the law. For instance – National Insurance Corporation Vs Span International Limited, Civil Appeal of 2002 No. 13 – The matter was based on the contract of Insurance. This indicates the essence and enforceability of contract law and how it facilitates in protecting parties and their interests and hence providing a platform for dispute resolution. Relevancy of Law Contract. The law it ensures that parties honors agreements and business transactions and setting standards and protecting interests BASIC ELEMENTS/ESSENTIALS REQUIRED IN FORMATION OF A VALID CONTRACT IN LAW 1. Consent 2. Offer 3. Acceptance 4. Consideration 5. Capacity 6. Intention to create legal relations. 7. Subject matter of the contract should be legally acceptable. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Consent - provides Section 2 of the contracts Act 2010, laws of Uganda – Defines consent to mean an agreement of two or more persons obtained freely, upon the same thing in the same sense. (Section 13 Contract Act of Uganda 2010) It is relevant to the element. Consideration – Means a right, interest, profit, or benefit accruing to one party or forbearance, detriment, loss or responsibility given suffered or undertaken by the other party. Acceptance – Section 2 of the contract Act 2010, Laws of Uganda – Refers to acceptance to mean an assent to an offer made by a person to whom the offer is made. Section 7, 3,5,4,8 of the contract Act 2010 are vital in respect to acceptance. Capacity - Section II of the contracts Act 2010 laws of Uganda provides for capacity. Section 12 of the contracts Act 2010, is vital. Offer According to Section 2 contracts Act 2010, Laws of Uganda offer means the willingness to do or to abstain from doing anything signified by a person to another, with a view to obtaining the ascent of that other person to the Act or abstinence. 1 Section 6 Contracts Act 2010 is vital. Section 7 Contracts Act 2010 is vital to the notion. 6. Intention to create legal relations. A lot will not be enforceable unless the parties have a clear intention to be bound legally. There must be a clear indication that the parties at the time of acting were willing to recognize their agreement as one with a legal status and it was intended to be enforceable in law. Relevant cases to the element o LENS V DEVONSHIE (1914) THE TIMES. o BALFOUR & BALFOUR (1919) Vol. 2 KINGS BENCH pg. 571 o MERRIT V MERRIT, 1970 Vol. 2. ALLER. Cardinal principles of the law of contract Freedom of contract this means all adult persons of sound mind have the liberty to enter into contractual relationships of their own choices as long as there are within the law Caveat emptor this means in simple buyer beware the principle of buyer beware very crucial in transactions relating to transfer of property. Relevancy of this principle I is to the effect that the buyer will enable him to decide to enter the contract or not. LAW OF CONTRACT A. NATURE OF A CONTRACT A contract may be defined as an agreement between two or more persons who intend to create legally binding obligations that are enforceable in a court of law or by binding arbitration. That is to say, a contract is an exchange of promises with a specific remedy for breach so that if one of the parties to the contract fails to do as per the contract, the offended party may sue and the court will award on appropriate remedy for breach. Contracts may fall into one or more of the following categories. a) Specialty Contract A specialty contract is a contract that must be in writing, be signed and sealed. It’s the presence of these three elements that make a contract specialty. However, it is not an absolute requirement that all contracts must be under seal. b) Contracts of Records These are contracts which do not require the consent of one party but are imposed on the other by persons or bodies with statutory authority. Such contracts are usually given by government bodies such as Court Order or summons, and Orders by Parliamentary committees. Failure to honour a contract of record is punishable as contempt. c) Simple Contracts These are the ordinary contracts made in the course of business and are not under deed but are enforceable by the courts. d) Contracts of Utmost Good Faith These are contracts in which complete and total honesty is a prerequisite of the contract. They are also called contracts of uberimae fidei. In these contracts, one party to the contract is usually more advantaged than the other in terms of information and knowledge. The utmost good faith principle requires that the person with an advantage must not use his advantage to exploit the other contracting party. He should therefore supply to the other party with all the relevant information. Examples of contracts uberrimae fidei are those between insurance companies and the policy holders. The insurance company has detailed 2 information on what they cover and the insured usually has a much greater knowledge about the thing insured against so that both parties have to contract under utmost good faith. e) Executed and Executory contracts To execute means to carry out an obligation or task. An executed contract is, therefore, a contract where both parties have fully performed their duties in the contract and nothing is left to be done. On the other hand, an executor contract is a contract which has not yet been performed or executed. Such contracts mean that something has to be done by one or both parties to the contract. For example, if B delivers goods to C and C promises to pay for them at a future date, C will have not executed his part of the contract and the contract is therefore executory. f) Voidable Contracts These are contracts that are legally binding when formed but can be avoided by one party at his option without any legal consequences. When a contract is voidable the law will allow one of the parties to withdraw from it if he wishes. A voidable contract remains valid unless and until the innocent party chooses to terminate it. Circumstances that make a contract voidable include non-disclosure of one or more material facts, some agreements made by minors, contracts induced by misrepresentation, duress, mutual mistake, lack of free will of a contracting party, or presence of one contracting party’s undue influence over the other, and a material breach of the terms of the contract. g) Void contracts These are contracts that cannot be enforced in a court of law either because they are illegal or they breach express provisions of the law. If a contract is void, then it is of no legal effect. Void contracts include those, which are prohibited by the law or are against public policy An example of such contracts is an agreement to carry out an illegal act such as a contract between drug dealers and buyers. In such a case, neither party can go to court to enforce the contract. A void contract is said to be void ab intio, i.e. from the beginning. Other examples of void contracts are contracts against public policy, some contracts that involve minors or persons with no contractual capacity or contracts that do not have elements of a valid contract. h) Unenforceable Contracts Unenforceable contracts are valid contracts which cannot be enforced by the courts because they may be technically defective according to the law. An example of such contracts is a contract of guarantee which is not supported by written evidence. A contract may be unenforceable because there is no remedy provided by the law for obligations of such a character, or because some prerequisite for the full validity of the obligation has not been performed or because the remedy has been lost. i) Illegal Contracts. These are contracts that involve a criminal element. They cannot be enforced in a court of law e.g. contracts to commit a crime. j) Bilateral contract This is a contract that creates binding obligations on both parties to the contract. k) Unilateral contract This is a contract that creates binding obligations on one of the parties only e.g. promising a reward to whoever finds your lost item. No body is under obligation to look for the item but if the item is found there is a obligation to give the promised reward. QUESTIONS 3 Explain the role of law of contract in a modern economy Define a contract Discuss the different types of contract B) FORMATION OF CONTRACTS The law gives people the freedom to contract on terms that they deem fit based on their circumstances. However, for such contracts to be enforceable, they must have the essentials of a valid contract. The essential elements of a contract are the fundamental principles upon which a valid contract is found and upon which the lack of one render the contract void, voidable or unenforceable. These elements are as follows: 1. There must be an offer An offer is the starting point of contract formation. An offer is an expression of willingness to contract on certain terms provided that these terms are in term accepted by the party or parties to whom the offer is addressed. The person who makes an offer is known as the offeror while the person who accepts the offer is the offeree. According to Section 2 contracts Act 2010, Laws of Uganda offer means the willingness to do or to abstain from doing anything signified by a person to another, with a view to obtaining the ascent of that other person to the Act or abstinence. Section 6 Contracts Act 2010 is vital. Section 7 Contracts Act 2010 is vital to the notion. An offer must therefore constitute the following three elements: It must be an expression of the willingness to do or to abstain from doing something. Such expression of willingness must be made to another person since there cannot be a proposal by a person to himself. The expression of willingness must be made with a purpose to obtain the assent of the other person. The person making an offer is called an offeror or promisor, and the person to whom the offer is made is called the offeree; while the one accepting the offer is called the acceptor or promise. Types of offer Counter offer This is a reply to an offer whose effect is to vary the terms of the original offer. It is in fact an offer in itself, which operates as a rejection of the original offer. Cross offer Where A offers his property to B and B, without knowing about A’s offer also offers to buy the same property from A, each of these offers is a cross offer of the other and therefore no contract can result from them alone. A must specifically accept B’s offer or B that of A if a valid contract is to be made. Conditional offer This is an offer which is made subject to a condition e.g. to be accepted within specific time. Rules governing an offer An offer may be made either orally or in writing or by conduct. An offer is made by conduct where it is implied. For example, boarding a Public Service vehicle is an implied acceptance to pay for the benefits received. 4 An offer may be specific or general. An offer is specific if it is made to a specific person or to any member of a specific group of persons. A specific offer can only be accepted only by the specified persons or group of persons it is made to. Example, an offer by John to sell to Jill his car is a specific offer because it has identified the person to whom the offer is directed, thus only Jill can accept it. Again, a specific offer to a group of persons will identify the group to which the offer is directed. For example, an offer to Manchester United team players can only be accepted by a member of that group only. On the other hand, an offer may be general if it is made or addressed to the world at large and anybody may accept it. An example of this is type of offer is an offer made in an advertisement. A general offer is an offer to the world at large and any person can or may accept the offer. Once the offer is specific, its acceptance can only be made by the targeted offeree, otherwise it will not be binding on the offeror. An exception arises where the offer is made to the general public. A case in point is Carlil vs Smoke Ball Co. (1893) 1 OB 256. In this case Smoke Ball Co. ran an advert claiming a scientific success in a drug fighting influenza. As guarantee of their success they offered to pay 100 pounds to any person who used their drug to a proper prescription and still contracted the disease. As fate had it Ms. Carlil applied the drug but contracted influenza, hence the suit for recovery of the money. Smoke Ball Co. denied liability claiming that the offer had not been addressed to the plaintiff specifically. That therefore, her purported acceptance was not binding on the company. Court held that the company was liable. An offer must contemplate to give rise to legal relation; for example an offer to a friend to dine at the offeror’s place is not a valid offer at all. The offer must be firm and final. The offeror must not merely be initiating negotiation from which an agreement may or may not result. He must be prepared to implement his / her promise if such is the wish of the other party. An offer must be conclusive in nature and must leave no room for further negotiations. The terms of an offer must be certain and not vague. To this extent, it has been held that unless all the material terms of a contract are agreed, there is no binding obligation. Therefore, an agreement to agree in future is not a contract because the terms of the agreement are uncertain. However, the offer may be made subject to any terms and conditions. Where a condition attached to an offer is not fulfilled, the offer fails and no contract can result from it. An offer must be communicated to the offeree. Doing anything in ignorance of the offer does not amount to acceptance. This rule applied to both specific and general offers. If the offer contains special terms, they too must be communicated to the offeree before a proper acceptance of the same is made. An offer becomes effective when it is communicated to the offeree e.g. If B found A’s lost dog and not having seen the advertisement by A offering a reward for its return, returns it out of goodness of heart, B will not be able to claim the reward. This principle was illustrated in the case of Fitch v Snadakar; a two hundred US Dollars reward was offered for the arrest of a criminal. The plaintiff who was not aware of the reward apprehended the criminal and later claimed the reward. Court held that the claim must fail as he was not aware of the offer when he arrested the criminal. An offer should be distinguished from an invitation to treat. An invitation to treat is simply an expression of willingness to enter into negotiations which, it is hoped, will lead to the conclusion of a contract at a later date. The distinction between a specific offer and an invitation to treat is primarily one of intention: did the marker of the statement intend to be bound by acceptance of his terms without further negotiation or did he only intend his statement to be part of the continuing negotiation process? Thus, the court must examine carefully the correspondence which has passed between the parties and seek to identify from the language used and from the actions of the parties whether, in its opinion, either party intended to make an offer which 5 was capable of acceptance. Accordingly, an invitation to treat is a mere invitation by a party to another or others to come make offers. A positive response to an invitation to treat is an offer. Difference between an offer and an invitation to treat An offer differs from an invitation to treat. The major characteristic of an offer is that once it is accepted, it results into a binding contract. An invitation to treat on the other hand is an arrangement written or verbal welcoming parties into negotiations before the two can ultimately enter into a valid contract. In Mayanja Nkangi vs. NHCC (1972) 1 ULR 37, the plaintiff claimed that on the 10/6/1964 he had received a letter from the Minister of housing which offered the recipient an opportunity of hire-purchasing a house in Kampala. Pursuant to the letter; the plaintiff made arrangements and met the Permanent Secretary who showed him a document roughly outlining the main points of the terms of the agreed purchase and an initial payment of 20% of the purchase price and a period of payments to be over 15-20 ears; at the option of the purchaser. In September, 1964 the plaintiff met the Minister and the purchase price of 5,000 pounds was arranged. The plaintiff then sent a cheque of 1000 pounds and was given a receipt by NHCC. By Statutory Instrument, the Minister of Housing and Labour ordered the transfer to NHCC of several government properties then vested in the Uganda Land Commission. The actual transfer was made from 1/04/1965. The house paid by the plaintiff was equally affected by this order. He sued claiming that by paying the 20% of the price value a valid contract had been entered and therefore sought an order for specific performance for breach of the contract. It was held that the initial letter from the Minister of Housing was a mere invitation to treat. Secondly, that there was no contract because the transaction relied upon by the plaintiff was still in the course of negotiations and that no concluded contract was made between the parties. In Bell vs. Fisher, a display of a flicker knife was held to be a mere invitation to treat. An invitation to treat may take any of the following forms; a. Advertisements The general rule is that an advertisement in the newspapers or other media is an invitation to treat rather than an offer.. Advertisements are treated as invitation to treat because if they were treated as offers the advertiser might find himself contractually obliged to sell more goods than he in fact owned. Nevertheless there are certain cases where an advertisement may be interpreted as an offer rather than an invitation to treat. This depends on the nature of the advertisement and the wording thereof. Lord parker CJ in Partridge v Crittenden (1968) held that the advertisement was an invitation to treat and not an offer. In Partridge V Crittenden where a person was charged with ‘offering’ a wild bird for sale contrary to the law after he had placed an advert relating to the sale of such birds in a magazine. It was held that he could not be found guilty of offering the bird for sale as the advert amounted to an invitation to treat not an offer. The classic example is the case of Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Balls Co (1893 vol.1 QB pg. 256). In that case the defendants were the manufacturers of the carbolic smoke balls. They issued an advertisement in which they offered to pay $ 100 to any person who caught influenza after having used one of their smoke ball, in the specified manner. They deposited £ 1,000 in the bank to show their good faith. The claimant caught influenza after using the smoke balls in the specified manner. She sued for the £ 100. The defendants claimed that their advertisement was an invitation to treat thus not bound by the acceptance of the claimant. It was held that the advertisement was not an invitation to treat but was an offer to the whole world and that a contract was made with those persons who performed the conditions ‘on faith of the advertisement’. The claimant was therefore entitled to recover £100. b. Display of Goods for Sale 6 The display of goods for sale in a shop or supermarket with price labels attached thereon is an invitation to treat not an offer. The case to illustrate this is Fisher V Bell in which a shopkeeper was prosecuted for offering offensive weapons for sale, by having flick knives on display on his window. It was held that the shopkeeper was not guilty as the display in the window was not an offer for sale but an invitation to treat. The reasons why the courts decided not to regard this as an offer was explained by Lord Goddard in Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists (1953 vol.1 QB pg. 401). In that case, the defendants, Boots Cash Chemists, operate a self-serve pharmacy where customers selected the articles from the shelf and then proceeded to the cashier to pay for them. Among the articles for sale were pharmaceutical products which, according to the Pharmacy and Poisons Act, were required to be sold only under the supervision or authorization by a pharmacist. On 13th April, 1951, two customers purchased a pharmaceutical product governed by the Act. It was held, a display of items in a store is an invitation to treat, that is, a non-binding invitation to receive offers. The presentation of the item by the customer to the cashier constitutes an offer to purchase the item. The contract is completed with the cashier’s acceptance of the customer’s offer. Therefore, the sales in question were completed under the pharmacist’s supervision and, as such, were legal sales under the Act. It should be noted that declaration of intention and mere statement of information doesn’t constitute an offer. This position is illustrated in Harris Vs Nickerson [1873]. An auctioneer advertised that there would be a sale of office furniture. The plaintiff a prospective buyer traveled to London to attend to sale but all the furniture was withdrawn. He sued for loss of time and traveling expenses. It was held that the auctioneer was not bound to sell the furniture as he was merely stating his intentions to sell and not making an offer which by acceptance wound be transformed into a contract. The advertisement for bids in an action is mere invitation to treat. The sale is complete when the hammer falls and until that time the bid may be withdrawn. c. Tenders Tenders for the supply of a specified quantity of goods during a specified period of time to a group of persons or the whole world are invitations to treat not offers. The advertisement constitutes an invitation to treat and a trader’s response thereto is the offer which may be accepted or be rejected. d. Sale by Auction The general rule is that an auctioneer, by inviting bids to be made makes an invitation to treat. The offer is made by the bidder which in turn, is accepted when the auctioneer strikes the table with a hammer. e. Declaration of Intention A declaration of intention to do something is not an offer but an invitation to treat even if the declaration on the face of it appears to be an offer. An example is the case of Harris v Nickerson (1873) in which the defendant advertised that an auction of certain goods would take place at a stated time and place. The plaintiff travelled to the auction only to find that the items that he was interested in had been withdrawn. He claimed compensation for breach of contract, arguing that the advertisement constituted an offer, and his travelling to the auction, an acceptance by conduct. The court held, that the advertisement was not an offer; it was merely a declaration of intention so that the traveler could not sue the advertiser for breach of contract if the auction is cancelled, or some of the goods to be auctioned are withdrawn. The case law relating to offers has established the following rules as the components of a valid offer. First, the offer may be oral, written or may be implied from the conditions of the offer. In this regard, the manner of communication of the offer to the intended parties is immaterial provided it is communicated. Secondly. An offer must be specific or definite. This means that the offer must be in such a manner as to enable the offeree to understand the intention of the offeror and consider his response thereto. Accordingly, a vague offer cannot stand. The case in point is Scammel and Nephew Ltd. v Quston in which an offer that referred to “hire purchase terms” 7 over a period of two years was declared “void” due to uncertainty over the meaning of “hire purchase terms”. A person cannot be said to have accepted an offer with such conditions: he would not have understood what he was purporting to accept. Where the offeror is asked to explain a vague offer, he must do so. The case in point is Stevens v Mclean. Third, an offer may be conditional or unconditional. Where an offer is a conditional, the conditions stipulated by the offer must be satisfied before the offer can be accepted. On the other hand, where no conditions are attached to the offer, the offer is acceptable as it is made. Fourth, an offer can be made to a specified person, group or to the general public. Fifth, an offer may prescribe the duration the offer is to remain open for acceptance. This means that acceptance must be with the duration stipulated in the offer so that accepting it after the lapse of the given duration cannot constitute a valid offer. Termination of offer An offer lapses or may be terminated and becomes invalid under the following circumstances (relevant legal sections. 5 and 6 of the Contracts Act of Uganda 2010). An offer may be terminated by a number of ways such as; Revocation, Lapse of time, Counter-offer, Death or Insanity of the parties, Rejection and failure of a condition subject to which the offer was made, i.e. frustration of contract. a. Revocation Revocation involves the offeror withdrawing his offer either expressly or impliedly. Revocation must satisfy the following two conditions in order to be valid. First, it must be made before acceptance of the offer. This position was held in Byme v Van Tien Hoven (1880), where a letter of revocation posted after a letter of acceptance had been posted, the revocation was held to be ineffective although the offeror did not know that the offeree had posted the letter of acceptance. Second, revocation must be communicated to the offeree either expressly or impliedly. An example of the implied revocation is the case of Dickinson v Dodd’s, in which James L.J explained in part that an offer can be revoked even though it was declared to be open for a given period provided the same is communicated to the offeree. Thus, offeror can change his mind at any time before the period expires. However, revocation will not be possible if consideration was given for keeping the offer open. Such an offer constitutes an “Option”. An example is a hire purchase agreement where the owner of goods cannot tell the hirer that he will not, after all, sell the goods to him. Second, an application for shares in a company made in response to a prospectus cannot be withdrawn until after the expiration of the third day after the time of opening of the subscription lists. b. Lapse of time An offer comes to an end automatically by operation of law if it is not accepted within the stipulated time if any, or if it is not accepted within what appears to the court to be the reasonable time. After passage of stipulated time or reasonable time. When an offer is not accepted within the stipulated time after its communication to the offeree, or within a reasonable time, where no specific duration of acceptance is given, then such an offer comes to an end. A reasonable time is a question of fact depending on the circumstances of each case. In Ramsgate Victoria Hotel Co. v Montefiore (1866), an offer to buy shares in a company could not be accepted at the end of the fifth month after the offer was made. Further, an offer will be terminated for lapse of time if it is executed before the offeree accepts it as was the care in Dickson’s v Dodd’s (1876). In that case, there was an offer to sell property which was however sold to another party before the offeree accepted the offer. The court regarded the sale as equivalent to the offerors’s death because it rendered performance of the offer impossible. c) Counter-offer 8 A counter-offer is a purported acceptance which does not accept all the terms and conditions proposed by the offeror but instead it introduces new terms. A counter-offer is treated as a new offer which is capable of acceptance or rejection. It therefore ‘kill off’ the original offer. A case in point is Hyde v Wrench (1840), in which the acceptance to buy the house for £950 was held to have cancelled the original offer to sell it at £1,000. d. Death or Insanity of either Party The death of either party before acceptance terminates a specific offer. The reasoning for this position is that once an offeror dies his offer cannot be accepted because there will be no one to contract with. The case in point is Bradbury v Morgan Mellish (1862). Additionally, the unsoundness of mind of either party before acceptance terminates the offer. However, the offer only lapses when notice of the insanity of the one is communicated to the other party to the contract. e) Rejection This is the refusal by the offeree to accept the offer. The refusal may be expressed or implied. It is implied where the offeree remains silent. Silence on the party of the offeree amounts to rejection. For instance, in Felthouse v Brindley, Pual Felthouse offered to buy a particular horse from his nephew and stated in a written offer that ‘if I hear no more about him, I consider the horse mine at £ 30, 15s’. His nephew did not reply but instructed the auctioneer, Bindley, not to sell the horse. However, Bindley mistakenly sold the horse and Felthouse sued the auctioneer for conversion. The question was whether there was a contract between Felthouse and his nephew for the sale of the horse. The court held, that Felthouse could not impose a sale of the horse on his nephew by requiring him to notify. Felthouse if he did not wish to sell on those terms. There was no communication of acceptance before the sale hence the nephew was not bound to sell to Felthhouse the horse on the day of the auction. The rationale in this case is that the silence of the nephew did not amount to acceptance. f) When a condition precedent has not been met Offers made on the basis of a condition precedent or state of affairs existing lapses if the condition or state of affairs fail to materialize. Such offers are referred to as conditional offers. In Financings Ltd v Stimson (1962), D signed an “offer to buy” a car on hire-purchase from a finance company. The document had been given to him by the car dealer. He paid the first installment, insured the car and took it away. However, he was unhappy with its performance and decided to return it to the dealer and cancelled his insurance. The car was subsequently stolen from the dealers and damaged. Not knowing of this the finance company then accepted the written offer which had been sent to them. D refused to pay the charges and the Company sued him for breach of the hire purchase agreement. It was held that D’s offer was subject to an implied condition that the car should continue in its undamaged state and that on the failure of that condition, the offer lapsed. h) An offer comes to an end if not accepted in a manner prescribed (failure of a condition subject to which an offer was made). When acceptance is made by a mode different from one that was preferred. This is more so where the offeror has insisted that acceptance must conform to the proposed mode. In Ellason Vs Henshaw (1819); the plaintiff offered to buy flour from the defendant requesting the reply to be sent with the Wagon driver who communicated the offer. The defendant communicated the acceptance by post office. The driver reached before the letter was received. Court held that there was no contract between the two parties. QUESTIONS Discuss the rules that govern an offer Under what circumstances may an offer be terminated Distinguish between an offer and an invitation to treat 9 2. There must be Acceptance This is the second condition of a valid contract. Acceptance is an unqualified expression of assent to the terms proposed by the offeror. Acceptance may be express or implied by conduct as was in the Carlill case. An acceptance must be clear in the sense that it must accept all the terms of the offer and must not introduce conditions or new terms. A purported acceptance which does not accept all the terms and conditions proposed by the offerer but which introduces new terms is a counter-offer and is treated as a new offer which is capable of acceptance or rejection. By acceptance an agreement comes into existence between the parties because the parties will have reached Consensus ad idem i.e, meeting of the minds. An acceptance means the assent to an offer made by a person to whom the offer is made (Section.2 of the Contracts Act of Uganda 2010). Thus, acceptance is the manifestation by the offeree of his assent to the terms of the offer. Section 7, 3,5,4,8 of the contract Act 2010 are vital in respect to acceptance A valid acceptance must adhere to the following rules (Section.7 of the contract Act 2010, laws of Uganda) 1. As a general rule, acceptance must be communicated to the offeror. Thus, acceptance cannot be implied from mere silence on the part of the offeree. Thus, an offeror cannot impose a contractual obligation upon the offeree by stating that unless the later expressly rejects the offer, he will be held to have accepted it.(Felthuse V Bindley) Further, acceptance is validly communicated when it is actually brought to the attention of the offeror. In this regard, it ought to be made in the absence of any disruption such as noise or otherwise. In Entores v Milles Far east Corp (1952) for instance, the court held that an oral acceptance drowned by an over-flying plane, such that the offeror cannot hear the acceptance is no acceptance and creates no contract unless the offeree repeats his acceptance once the plane or the noise has passed over. A similar example is where a telephone line goes ‘dead’ or an internet link breaks before acceptance is made. under such circumstances, the acceptance is incomplete. However, where acceptance is made clearly and audibly but the offeror does not hear what is said, acceptance is said to be complete unless the offeror makes it clear to the acceptor that he did not hear what was said. However, the rule requiring communication of acceptance has a number of exceptions as follows: 1. An un-communicated acceptance will be effective if, from the words of the offer, the offeror can be regarded as having waived the right to be informed of the acceptance: in Carlill v carbolic Smoke Ball Co. Mrs. Carlill was regarded as having accepted the defendant company’s offer even though she had not told them that she would buy and use the carbolic smoke balls. Second, an offer made to the general public can be accepted by anybody who fulfills, or performs, the conditions stated therein. A gain in Carlill case, Mrs. Carlill was held to have accepted the offer even though it had not been made to her personally. 2. Acceptance is complete the moment it is received by the offeror and at the place the offeror happens to be even in the case of instantaneous communication such as internet, telephone and telex. The case in point is Entores Ltd. v Miles For East corporation (1955), in which the court held that the contract was formed in London when the offeror received the telex message from Amsterdam. 3. An offer made to the general public can be accepted by any member of the public. For instance, an initial public offer of shares by a company can be accepted by any member of the public. However, an offer made to a particular person can only be accepted by that person. In Boulton v Jones, the court held that an offer made by Jones to Brocklehurst could not be accepted by Houlton. Similarly, an offer made to a particular class of persons can only be accepted by a person of that class. for instance, in the case of 10 Wood v lectrike Ltd, an offer to “hair sufferers” was held to have been properly accepted by Mr. Wood, a young man, whose hair was prematurely turning grey and was regarded by the court as a “hair sufferer” within the terms of the offer. On the same reasoning, a rights issues offer can only be accepted by share holder of that company. 4. The acceptance of an offer must be unconditional. (Hyde V Wrench) Thus, the offeree must simply accept the offer the way it is without introducing new conditions for such conditions are regarded as a counter-offer which terminates the original offer. 5. Once an offer has been terminated, it cannot be revived by a subsequent tender of performance thereof. The implication of this condition is that the offeree must accept the offer before it is terminated and that the acceptance thereof must be in the prescribed manner so as not to terminate it. Consequently, where the offeror prescribes a specific method of acceptance and has used clear words to achieve this purpose, the general rule is that the offeror is not bound unless the terms of his offer are complied with. However, where the prescribed method of acceptance is not clear, the court will hold the offeror to be bound by an acceptance which is made in a form which is no less advantageous to him than the form which he prescribed. This position was considered in the case of Manchester Diocesan Council for Education v Commercial and General Investments Ltd 1969) in which the claimant decided to accept the defendants tender by sending his letter of acceptance to the defendant’s surveyors but not to the address on the tender as prescribed by the offeror. The court held, that communication to the address in the tender was not the sole permitted means of communication and that the defendant was not disadvantaged in any way by the notification of acceptance being given to its surveyors. Therefore, there was a valid contract. 6. An acceptance in ignorance of the offer is not a valid acceptance. In this regard, for there to be acceptance, there must be a definite offer which is mirrored by a definite acceptance. For example, if X offers £ 100 as a reward for the safe return of his missing dog and Y returns the dog but is unaware of X’s offer, Y cannot claim the reward since he was not aware of the offer when he was returning the dog. The case in point is R v Clarke 263 in which the court held in this regard that an offer must have been present in the mind when any act which constitutes acceptance is undertaken. This position also holds where the party claiming the reward had forgotten about the offer of a reward at the time he gave the information. 7. Acceptance may be subject to a contract. In this regard, the words ‘subject to contract’ mean that the parties concerned do not intend to be bound until a formal contract has been drawn. In Eccles v Bryant, (1948) B sold a house to E “ subject to contract”. E signed his part and posted it to B but B did not sign his part. The court held that there was no contract between them unless B signed it. 8. Acceptance may be communicated through the post office. Such acceptance is subject to the postal rule of acceptance. Under this rule, the general position is that acceptance by post is complete on the date when a properly stamped and addressed letter of acceptance is posted and that it is immaterial that the letter is lost or destroyed or delayed in the post office. Illustration 1 Day 1: A makes an offer to B. Day 2: A decides to revoke the offer and puts a letter in the mail to B revoking the offer. Day 3: B puts a letter accepting the offer in the mail. Day 4: B receives A’s revocation letter. Note that in this illustration the letter of revocation can be effective only when the offeree gets it on the fourth day. However, a contract was formed on the third day when the letter of acceptance was posted so that it is too late for A to revoke the offer. B can therefore sue A for breach of contract. In Adams v Lindsell, (1818), the defendant sent a letter offering to sell some wool to the plaintiff on 2 September. The letter reached the plaintiff on 7 11 September. On that evening the plaintiff posted acceptance, and this was received by the defendant on September 9. However, the defendant sold the wool on September 8. It was held that there was a valid contract because the acceptance was posted without any delay. The defendant was therefore held liable. Illustration 2 Day 1: A makes an offer to B. Day 2: B intends to reject the offer by putting a letter in the mail to A rejecting the offer. Day 3: B changes his mind and sends a fax to A accepting the offer. Note that in this situation, whichever communication A receives first will determine the contractual position. Illustration 3 Day 1: A makes an offer to sell a parcel of land to B. Day 2: B mails her acceptance. Day 3: Before A receives B’s acceptance, B telephones A and states she wishes to reject the offer. Day 4: B’s original letter of acceptance arrives and, A then records the contract as a sale. Note that in this scenario, B’s acceptance of the offer means there is a binding contract; she is obliged to pay for the land or be liable for damages. Day 1: A makes an offer to sell a parcel of land to B. Day 2: B mails her acceptance. Day 3: Before A receives B’s acceptance, B telephones A and states she wishes to reject the offer. Day 4: B’s original letter of acceptance arrives; A then records the contract as a sale. B’s acceptance of the offer means there is a binding contract – she is obliged to pay for the land or be liable for damages. Finally, it should be noted that the two elements-offer and acceptance-give rise to consensus, hence an agreement. Thus, they constitute the foundation of every contractual relationship but cannot themselves constitute a contract. 3. There must be Consideration. This is another requirement for valid contracts. It generally denotes anything of value promised to another in exchange of what the other is giving when making a contract. Consideration is only sufficient if there is a detriment to the promisor or benefits to the promise but it is not necessary that the benefit should go to the promise. A valuable consideration, in the sense of the law, may consist either some right, interest, profit or benefit accruing to the one party, or some forbearance, detriments, loss or responsibility given, suffered or undertaken by the other’. (as per the case of Currie V Misa 1875). In the case of Currie v. Misa (1875) where Lush J. said: "A valuable consideration, in the sense of the law, may consist either in some right, interest, profit or benefit accruing to the one party, or some forbearance, detriment, loss, or responsibility, given, suffered, or undertaken by the other." Consideration is the price I pay to buy your promise. So, briefly, consideration is something, which is of value to you, which I give you to buy your promise. If you make me a promise but I do not give you consideration, your promise is gratuitous. Generally, the Law does not impose a contractual obligation on a person who makes a gratuitous promise. Consideration may take the form of money, physical objects, services, promised actions, abstinence from a future action and much more. The most important point to note is that consideration is the benefit flowing to each party. 12 Thus if A agrees to sell his car to B for £ 1000, the £ 1000 is the consideration so that A will get £ 1000 while B’s consideration is that car. Again, if A signs a contract with B such that A will paint B’s house for USD 500, A’s consideration is the service of painting B’s house, and B’s consideration is USD 500 paid to A. it is therefore important to note that in bilateral contracts, consideration is constituted by the mutual promises made by the parties. Consideration may be executor or executed. Consideration is executed when one of the two parties has done all he is bound to do under the contract or when one of the parties to the contract has fulfilled his obligations. For example, where A pays for the goods before they are delivered, A will have performed his side of the obligation by paying. Again, where A offers £ 50 reward for the return of her lost handbag, if B finds the bag and returns it, B’s consideration is executed. On the other hand, consideration is executor when there is a promise to do something in the future, that is, when both parties have not fulfilled their promises to one another. For example, in a bilateral contract for the supply of goods whereby X promises to deliver goods to Y at a future date and Y promises to pay on delivery, both parties will not have fulfilled their obligations to the contract. The contract will therefore be executor. If X does not deliver the goods as agreed, he will be in breach of the contract and Y can sue. Types of consideration Consideration can be; …ZExecutory consideration: consideration is said to be executory where there is an exchange of promises to perform acts in the future Executed consideration: consideration is executed when the promisee does an act in return for the promisor's promise. Past consideration: consideration that is given before the promise is made, and the consideration and the promise are not part of the same transaction. Consideration is governed by a number of rules as follows. The first rule is that consideration must not be past. This is the general rule. In this regard, past consideration is no consideration. This means that consideration must be on the performance of the agreement but not for the discharge of a past obligation for past consideration is not valid and cannot be used to sue on a contract. Rose v Thomas 1842 vol 114 English law report. The general rule is that past consideration is not sufficient consideration. This means that if the consideration, which the promisee has given the promisor, is past consideration, the promisee is unable to enforce the promisor's promise. In Re McArdle [1951] Ch 669, the claimant had spent her own money in improving a house belonging to some relatives. After the improvements had been carried out, the relatives signed a document promising to pay her the money she had spent on improvements. They failed to honour their promise and the claimant sued them to enforce the promise. She did not succeed, as she had done the improvements before the relatives had made the promise, and the court was unwilling to treat the claimant's consideration (i.e. doing the improvements) and the relatives' promise as part of the same transaction. Exception to the past consideration rule If the promisor requested the promisee to carry out the act constituting the past consideration. In Lampleigh v. Brathwait (1615) , Brathwait had killed a man and asked Lampleigh to meet the King and get him a pardon. Lampleigh met the King and obtained the pardon. Brathwait promised Lampleigh that he will pay Lampleigh £100 for his services. But as Brathwait did not honour this promise Lampleigh sued him. The court held that Brathwait's prior request to Lampleigh contained an implied promise to pay him a 13 reasonable sum for his services, and that the subsequent mention of the £100 was merely fixing the sum. The court treated the prior request and the subsequent promise as part of the same transaction. Consideration must be bargained for, it means that before a promise or act can be regarded as consideration it must be established that it was given in return for a promise here fore it must have been requested for so a certain it doesn’t merely arise because of performance on the act. Consideration must move from promise. It need not move to the promisor. This rule is meant to ensure that only parties for a contract who has paid a price for that contract can take benefits imposed from it or have burdens imposed on them by the contract. The promisor is the person who makes the promise. The promisee is the person to whom the promise is made. In Tweddle v. Atkinson, (1861) 1 B. & S. 393; Tweddle and William Guy entered into a written contract, by which they agreed to give money to William Tweddle. William Guy did not give the money promised. After his death, William Tweddle sued Guy's estate to enforce Guy's promise. He did not succeed, as he was not a party to the contract and did not give consideration to buy Guy's promise. It was stated that consideration must move from the party entitled to sue upon the contract." Consideration must be sufficient but need not be adequate The promisee's consideration does not have to be fair or equal in value to the promisor's promise. If one of the parties has made a bad bargain, the courts expect him/her to stick with it. In Thomas v. Thomas (1842) 2 Q.B. 851, the defendants promised to convey a cottage to the claimant, and in return, she promised to pay £1 per year as rent. The court held that the defendants were bound by their promise as the claimant had given sufficient consideration. This case makes it clear that the court is not concerned with the adequacy of consideration. Consideration must be given only after the promise in order to make it enforceable. For example, when somebo dy digs your garden or washes your clothes before you asked them to do so, he/she cannot enforce payment because of the past consideration doctrine. This is because the acts were performed voluntary and therefore should not bind the other party. The case of Re McArdle (1951 AC pg 669) it is illustrative on this point. In that case a number of children, by their father’s will were entitled to a house after their mother’s death. During the mother’s life, one of the sons and his wife lived with her in the house. The wife made improvements to the house and at a later date all the children signed a document addressed to her, stating that they would repay her all the moneys she had spent on the house. The Court of Appeal held that the promise was based on past consideration because the document was signed after the work on the house had been done and was therefore not enforceable. However, this rule is subject to a number of exceptions as follows. First, if th e act constituting consideration was done at the promisor’s request, then it will constitute valid consideration. Thus, if the promisor has previously asked the other party to provide goods or services, then a promise made after they are provided will be treated as binding. In Lampleigh v Brathwait the defendant who had killed a Mr. Patrick, asked the plaintiff to endeavour to obtain a pardon for him from the King. The plaintiff thereafter exerted himself to this end, “riding and journeying at his own charges from London to Royston, when the King was there, and to London and back, and so to and from New market to obtain pardon for the defendant for the said felony”. After the pardon was granted by the King the defendant promised to pay the plaintiff £ 100 for his endeavor’s but failed to honour the promise. When sued for the £100 the defendant pleaded past consideration but the court held found him liable because he asked the plaintiff to endeavour to obtain a pardon for him for the King. 14 Second, if so mething is done in a business context and it is clearly understood by both sides that it will be paid for, then past consideration will be valid. Accordingly, if you ask someone to do something for you which will cost them some money, you will be under an implied legal obligation to pay a reasonable amount as compensation for the anticipated expenses. In this regard, when you later on promise to pay some money after the thing has been done, you are merely fixing the reasonable amount which the law all along expected you to pay so that the service rendered is not past consideration. In Re Casey’s patents, Stewart v Casey (1892 vol. 1 CH pg 104), patents were granted to Stewart and another in respect of an invention concerning appliances and vessels for transporting and storing inflammable liquids. Stewart entered into an arrangement, with Casey whereby Casey was to introduce the patents. Casey spent two years “pushing” the invention and then the joint owners of the patent rights wrote to him as follows: “In consideration of your service as the practical manager in working our patents, we hereby agree to give you one-third share of the patents”. Casey also received the letters patents. Sometime later Stewart died and his executors claimed the letters patent from Casey alleging that he had no interest in them because the consideration for the promise to give him a one-third share was past. It was held that the agreement was binding. The reasoning for this position was stated by Lord Scarman in the following wards: An act done before the giving of a promise to make payment or to confer some other benefit can sometimes be consideration for the promise. The act must have been done at the promisor’s request the parties must have understood that the act was to be remunerated further by a payment or the conferment of some other benefits, and the payment, or the conferment of a benefit must have been legally enforceable had it been promised in advance. 270 . Third, under the Bill of exchange Act, the promise would be legally enforceable had it been made prior to the acts constituting past consideration. The Act provides in this regard that valuable consideration for a bill may be constituted by an antecedent debt or liability, which is deemed valuable consideration whether the bill is payable on demand or at a future time. The second rule about consideration is that it must have some economic value but need not be ‘adequate.’ This rule is to the effect that provided consideration has some economic value, the courts will not investigate into its adequacy. Where consideration is recognized by the law as having some value, it is described as “real” or “sufficient” consideration. Thus in Thomas v Thomas, (1842 vol. 2 pg. 851) the promise to pay £ 1 per annum rent was “ sufficient” to support the promise of a right to live in a house. The fact that £ 1 per annum was not a commercial rent was irrelevant, because the courts do not concern themselves with issues of adequacy of consideration. In this regard, it is not the business of the courts to measure the comparative value of the promisee’s consideration and that of the promisor in exchange for it. This rule is illustrated in the case of Chappell & Co.v Nestle Co. Ltd (1960 AC pg 87 or 199 vol. 2 ALL ER pg. 701) in which the court held that ‘ a contracting party can stipulate for what consideration he chooses if it is established that the promise does not like pepper and will throw the pepper away’. The third rule, is that consideration must move from the promise. This rule limits the persons who can seek the enforcement of rights in the contract to those who are privy to it. The rule is clearly illustrated in Price v Easton (1833), where a contract was made for work to be done in exchange for payment to a third party. When the third party attempted to sue for the payment, he was held to be not privy to the contract, and so his claim failed. Again, in a more famous case of Tweddle v Atkinson (1861), the plaintiff was unable to sue the executor of his father15 in-law, who had promised to the plaintiff’s father to make payment to the plaintiff, because he had not provided any consideration to the contract. Wightman J, said in this regard that ‘ no stranger to the consideration can take advantage of a contract although in his benefit’. The doctrine was further developed in Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre v Selfridge and Co. Ltd (1915), through the judgment of Lord Haldane. In that case, the appellants were motor-tyre manufacturers. They sold tyres to Messrs Dew & Co. who was motor accessory dealer under the terms of the contract Dew & Co. agreed not to sell the tyres below Dunlop’s list prices, and as Dunlop’s Agents, to obtain from other retailers a similar undertaking. In return for this undertaking Dew & Co, were to receive discounts, some of which they could pass on to retailers who bought tyres. Selfridge & Co accepted two orders from customers for Dunlop covers at a lower price through Dew & Co. and signed an agreement not to sell or offer the tyres below list price. It was further agreed that £ 5 per tyre so sold should be paid to Dunlop by way of liquidated damages. Selfridge supplied one of the two tyres ordered below list price. They did not actually supply the other, but informed the customer that they could only supply it at the list price. The appellants claimed an injunction and damages against the respondents for breach of the agreement made with Dew & Co. claiming that Dew & Co were their Agents in the matter. The court held, that there was no contract made between the parties. Dunlop could not enforce the contract made between the respondents and Dew & Co because there was no consideration. Even if Dunlop were undisclosed Principles there was no consideration moving between them and the respondents. The discount received by Selfidge was part of that given by Dunlop to Dew & Co. Since Dew & Co. were not bound to give any part of their discount to retailers, the discount received by Selfridge operated only as consideration between themselves and Dew & Co and could not be claimed by Dunlop as consideration to support a promise not to sell below list price. Haldane Viscount stated in this regard thus: My lords, in the law of England certain principles are fundamental. One is that only a person who is a party to a contact can sue on it… A second principle is that if a person with whom a contract not under seal has been made is to be able to enforce it, consideration must have been given by him to the promisor or to some other person at the promisor’s request (…) I am of opinion that the consideration, the allowance of what was in reality part of the discount to which messrs dew, the promise, were entitled as between themselves and the appellants, was to be given by Messrs Dew on their own account, and was not in substance any more than in form, an allowance made by the appellants. It should be noted that although Viscount Haldane spoke of “a second principle” it would appear that there is no “ second principle” as such. What appears to be a “second principle” is merely a verbal variation of the basic rule that consideration must move from the promise – for only then can he say that he is “ a party to the contract” and be entitled to sue on it as such. This rule that consideration must move from the promise is also known as the “privity of contract” rule and its effect is that an agreement between A and B for the benefit of C, if broken cannot, generally speaking, be enforced by C. However, the privity of contract rule has a number of exceptions which allow third parties to sue for contracts to which they are not privy. A third party may therefore sue under any of the following situations. First, a holder in due course of a bill of exchange can sue under the Bill of exchange Act even though there is no contract between him and any of the parties to the contract. Second, under the law of Agency, where the Agent makes a contract on behalf of his undisclosed Principal, the Principal may sue on that contract. Third, under the Road Traffic Act, a person injured in a car accident can sue the insurance company which insured the car against such risks although he is not a party to the contract between the owner of the car and the insurance company. Fourth, an assignee of a debt may sue the debtor in his own name under the Indian Transfer of Property Act. Fifth, a beneficiary under a trust may sue the trustee to enforce the trust obligations even though he was not a party to the contract creating it. Sixth, the assignee of a lease can enforce the terms of the lease against the original lessor. 16 The fourth rule about consideration is that it must not be the performance for an existing public duty. Thus, if the promise provides what he was required by public law to do in any event in return for a promise, performance of existing public duty is not good consideration. In Collins v Godfrey (1831), G promised to pay C for his giving of evidence. It was held, that Collins could not enforce the promise as he was under a statutory duty to give evidence in any event. However, if the promise provides more than what is imposed by public duty, then this is good consideration. The case in point is Ward v Byham (1956), in which a mother was under a statutory duty to look after her child. The ex-husband promised to pay her £1 a week if she ensured that the child was well looked after and happy. The court held that notwithstanding the statutory duty imposed on the mother, she could enforce the promise since the act of keeping the baby ‘happy’ provided additional consideration. Fifth, consideration must not be the performance of a contractual duty owed. In this regard, a promise to perform a pre-existing duty owed to one’s contracting party is not good consideration and cannot be enforceable in law. An illustrative case is Stilh v Myrick . Is that case, Stilh a seaman, agreed with Myrick to sail his boat to the Baltic Sea and back for £5 per month. During the voyage, two men deserted. Myrick promised he would increase Stilh’s wages if Stilh agreed to honour his contract in light of the desertions. Stilh agreed and on return to port, Myrick refused to pay him the extra wages. The court held that, Myrick’s fresh promise was not enforceable as the consideration. Stilh was merely performing a duty he already owed to Myrick under contract. Therefore, Myrick’s promise to increase his wages was not good consideration. Another point worth noting is the doctrine of part performance. A promise to discharge a debt by payment of part of it to discharge the whole debt is not good consideration. Thus a creditor would not be bound to accept part payment in settlement of the whole debt. This is also called the rule in Pinnel’s case (1602). In that case, Pinnel sued Cole for a debt of £8 10s. The defence was based on the fact that the defendant had, at the plaintiff’s request, tendered £5-2s -6d before the debt was due, which the plaintiff had accepted in full satisfaction for the original debt. Judgment was given for the plaintiff on a point of pleading on the ground that part payment of a debt could not extinguish the obligation to pay the whole debt. However, but for a technical hitch in the pleadings, the court would have made a judgment in favour of the defendant on the ground that the part payment had been made on an earlier day than that appointed in the bond. The debt could be discharged through the introduction of the creditor some new element but not due to part payment of the debt. Thus the rule in Pinnel’s case is that payment of a lesser sum on the day is satisfaction of a greater cannot be any satisfaction for the whole, because by no possibility a lesser sum can be a satisfaction to the plaintiff for a greater sum. This rule was confirmed in the case Beer of Foakes v (1884). In that case, Mrs. Beer recovered a judgment debt against Dr. Foakes for £2;077 17s 2d for debt and £13 is 10d for costs. On the 2st of December 1876 a memorandum of agreement was made and signed by Dr. Foakes and Mrs. Beer that, if Dr. Foakers paid £500 at once and the balance in installments of £ 150 on the first day of July and January or within one calendar month after each of the said days respectively in every year until the whole of the £ 2,090 was paid, Mrs. Beer would not ‘take any proceedings whatever on the judgment”. Dr. Foakes paid the whole sum of £ 2,090 19s as had been agreed. However, Mrs. Beer asked him to pay the interest accrued on the judgment. He refused to do so, relying on the agreement between him and Mrs. Beer. Mrs. Beer successfully sued for the interest after contending that the agreement between her and Dr. Foakes was unsupported by consideration. Dr. Foakes’ appeal to the House of Lords was dismissed with costs. Lord Selborne, stated that when Dr. Foakes paid the initial £500 he was merely doing part of something he was already legally bound to do by the court order of 11 August, 1875. When he completed paying the agreed installment he merely completed doing what he was already bound to do on 11 August, 1875. Mrs Beer therefore got nothing for her promise not to ask for interest that would accrue on the judgment date after 11 August, 1875. She was as a consequence free to break the promise. Thus, for an act to constitute sufficient consideration, it must be, that is, it must be something which the plaintiff was not already bound to do. 17 However, there are a number of exceptions to the rule in Pinnel’s case. In this regard, the rule that payment of a smaller amount of money cannot constitute consideration for a promise to accept it in settlement of a debt of a larger amount does not apply in the following situation. First, it does not apply where settlement is made in a different fashion at the request of the creditor. Second, it does not apply if the debt is paid in a smaller sum but at an earlier date or at a different place or location at the request of the creditor. Thus, if the debtor, at the creditor’s request, makes payments of a lesser sum before time, or in a different mode, or at a different place than appointment in the original agreement, the smaller sum constitute good consideration for the whole amount and the creditor claim any further. Third, it does not apply where the payment is made in kind. In this regard, a lesser sum can be a satisfaction to the plaintiff for a greater sum if the debt is paid in kind such as a gift of a horse, hawk, or robe, etc. in satisfaction of the whole debt. Fourth, it does not apply where there is a composition agreement with creditors. In this regard, where a debtor owes to many creditors more than he can pay, the creditors can agree together and reduce the debt on him such that each creditor gets part of the debt. Such part payment of the debt clears the whole debt such that any creditor who goes against the agreement will be held to be defrauding on others. 283. Fifth, he rule does not apply where there is a contractual duty owed to a third party. In his regard, where the promise performs a contractual obligation already imposed on him in favour of a third party, the promise so made by the third party is binding on him. Lastly, the doctrine of estoppels forms another major exception to the rule in Pinnel’s case. Thus, if A has by his own words or conduct made B to believe that a certain state of facts exists, and B has acted upon such a belief to his prejudice, A is not permitted to affirm against B that a different state of facts existed at the same time (Maclaine v Gatty 1921). The doctrine of estoppels was created to stop a party from going back to his original promise he had made to the other contracting party. This doctrine is well elaborated by Denning J, as he then was, in the famous case of Central London Property Trust ltd. v High Trees House Ltd (1947 KB pg 130), that where a party makes a promise intending to be acted on and it is acted on by the defendant, even though no consideration is present and the agreement is not under seal, the promisor is bound by his promise. The facts of that case were that the claimants leased a block of flats to the defendants on a 99-year lease at an annual rent of £2,500. In 1940 the defendants discovered that, as a result of the outbreak of the Second World War and the evacuation of people from London, they were unable to let many of the flats. So the claimant agreed to reduce the rent to £1,250. No express time limit was expressed for the duration of the reduction. From 1940 the property market returned to normal and the flats were fully let. The plaintiff company then claimed the full rent both retrospectively and for the future but the defendants refused to pay. The court held that a landlord who had promised to accept £ 1,250 instead of the contractual £ 2,500 as rent was bound by the promise and could not therefore claim the arrears but could demand again the payment of rent as originally agreed. The court was of the opinion that the agreement made in 1940 to reduce the rent was merely temporal and had ceased to operate in 1945. A number of points must be noted at this point. First, the doctrine of promissory estoppels operates only by way of defence and cannot operate as a cause of action. The case in point is Combe v Combe (1951 vol. 2 KB pg. 215 or 1951 vol.1 ALL ER pg. 767). In the case, the couple had divorced. The husband agreed to be paying her £100 per annum free of tax as part of her maintenance. However, he never made the payments but the wife never brought an action for maintenance because she was earning more than him. She later brought an action basing on promissory estoppels six years later. The Court of Appeal he that there was no consideration for the husband’ promise, and therefore the promise was not binding on him. Second, there must be a clear and unambiguous promise by words or by conduct for the doctrine of promissory estoppels to apply. (Woodhouse A C Israel Cocoa Ltd. SA v Nigeria produce C. Ltd (1972) AC 741, (1972) AL ER 271. Lastly, consideration must be legal. In this regard, an act or promise offered by the offeree as consideration for the other parties must not be a type of consideration prohibited by the law or is against the public policy. For example, a promise between O and Q to smuggle explosives to Kenya in return for £ 50 to be paid by B is an illegal consideration. 18 QUESTIONS Define consideration Discuss the rules that govern consideration State the rule in Pinnel’s case and the exceptions to it Doctrine of Privity of contract A contract is legally binding between the parties who make it thus creates a form of special legal arrangement for the parties who enter upon it. Consequently only such people are supposed to be part of it (parties) to the contract can normally sue or be sued on it. Tweedle v Atkinson (1861) I.B, Dunlop v Selfridge (1915) A.C 446. The both cases the parties sought to get a benefit out of the transaction to which they are not party to. However there exceptions such insurance and law of agency. The concept is based on the fundamental assumption of English law that a contract is a bargain such that he who takes no part in the bargain takes no part in the contract. In effect this means that no one can enforce another person’s promise unless he has been a party to the contract and that a stranger to consideration or to the contract cannot sue on that contract even if it is made for his own benefit. This expression is further illustrated in Dunlop Vs Selfridge [1915] The Plaintiff sold tyres to Dew Company where by Dew and company agreed not to sell the tyres below the price list provided and it was also agreed that Dew and company would obtain similar arrangements with other dealers. Dew and company sold the tyres to Selfridge and it was agreed that they would not sell the goods below the price provided. Selfridge breached this arrangement and Dunlop sued for breach of contract. Court observed that the plaintiff had no right of action because no consideration moved from Selfridges to them. This decision of Dunlop Vs Selfridges derives its basis of an earlier case of Price Vs Easton (1833) The defendant promised a one X that if he did some work for the plaintiff, the defendant would pay sum of money to the plaintiff. The obligations were performed as agreed but the defendant declined to pay the plaintiff. The plaintiff sued for breach of contract. It was held that no consideration had moved from the plaintiff to the defendant and as such the action would not be maintained. It should be noted however that this is a general rule and there are some exceptions to this rule. Agency A principal may sue or be sued on a contract made by his agent. This appears more apparent because the principal is the contracting party who has merely acted through the agent. Bill of exchange A holder for values of a bill of exchange (cheque) can sue prior parties on that cheque for example if A bought goods from B and paid by cheque which B endorsed or negotiates in favour of C for value, C acquires a right to sue A if the cheque is dishonored although no consideration moved from him to A . Assignment A person who proves that a right under a contract was assigned to him can sue under that contract in his own name. The law of trusts. 19 The law of trusts forms an exception in that a beneficiary (people entitled to benefit from the trust) acquires a right to sue the trustee if he intermeddles /interferes with the trust property for his personal benefit. Although the arrangement is between the settlor and the trustee, the beneficiaries though strangers to the arrangement can successfully sue on such contracts. Statutory exceptions e.g. Insurance contracts. In a life assurance and third party insurance policies, the beneficiaries can sue the insurance company. Restrictive covenants. These are rights or conditions that passed on with land. This is a negative term of the stopping one of the parties from doing something. They are common in land transactions where a person buys land from another and it is agreed that the restrictions on the use of land will run with the land. QUESTIONS Explain the doctrine of privity of contract and the exceptions to the rule 4. There must be an intention to create legal relation An intention to create legal relations is another essential element in any contract. The fact that parties have reached an agreement does not necessarily result in an enforceable contract unless the parties intend the agreements are not legally enforceable because they are not intended to create legal consequences. Examples of such agreements include domestic and social agreements and some commercial agreements. Ordinarily, commercial agreements are presumed to be legally binding although the court may rebut such presumption through the construction of the contact in question. A lot will not be enforceable unless the parties have a clear intention to be bound legally. There must be a clear indication that the parties at the time of acting were willing to recognize their agreement as one with a legal status and it was intended to be enforceable in law. Relevant cases to the element o LENS V DEVONSHIE (1914) THE TIMES. o BALFOUR & BALFOUR (1919) Vol. 2 KINGS BENCH pg. 571 o MERRIT V MERRIT, 1970 Vol. 2. ALLER. o The law demands that the parties must intend the agreement to be legally binding. After all if you invite a friend over for a social evening at your house, you would not expect legal action to follow if the occasion has to be cancelled. Intentions of a party determine the creation of a binding contract. In the case of Broomer vs. Palmer (1942) Lord Green said, “Law doesn’t impute intentions to enter into legal relationship where circumstances and the conduct of the parties negate any intentions of the kind” So it follows from this statement that statements which form the basis of the contract must contemplate legal consequences. For the purpose of establishing the intention of the parties, agreements are divided into two categories; business /commercial and social/domestic agreements. Business/commercial agreements In business agreements, it is automatically presumed that the parties intend to create legal relations and make a contract. This presumption can however be rebutted by the inclusion of an express statement to the effect that the parties do not intend to create legal relations. Domestic and Social agreements There is a presumption that the parties did not intend to create legal relations in domestic and social agreements. This group covers agreements between family members and friends. The law presumes that social agreements are 20 not intended to be legally binding because the parties never intend their agreement to be legally binding. You might agree to meet someone for lunch or accept an invitation to a party, but in neither case have you entered into a contract. This principle was illustrated in the case of Jones V Padavatton (1969) 2ALLER 616 where it was held that a mother who had promised her daughter that she would provide an allowance to allow the daughter to complete her legal studies was not liable for breach of contract when she later withdrew from the arrangement because it was a family arrangement and there was no intention to create legal relations The following agreements fall under this category. Agreements between husband and wife Where the husband and wife are living together amicably, there is a legal presumption that any agreement they enter into is not legally binding unless the parties are not of one mind. In Balfour v Balfour, the defendant and his wife were on leave in England. When the defendant was due to return to Ceylon, where he was employed, and his wife was advised to remain in England for health reasons on the promise that the defendant (husband) will be sending her £ 30 a month. He failed to pay and his wife sued on the contract. It was held that the husband was not liable because there was no intention to create legal relation. Atkins L J said in this regard that “it would be of worst possible example to hold that agreements such as this resulted in legal obligations which could be enforced in the courts… the small Courts would have to be multiplied one hundred fold if these arrangements were held to result in legal obligation”. This principle appears to be a consequence of a legal apprehension that ill-advised litigation will destroy the domestic tranquility generally prevailing in the home, or the love between the parties. However, this presumption will not apply where the spouses are not living together at the time of the agreement (separated) this was stated in the case of Merrit Vs Merritt (1970) 2ALL ER 760; the husband left his wife. He later agreed to pay 40 pounds per month for her maintenance. It was also agreed that she would pay off the outstanding mortgage after which the husband had promised to transfer the house into her name. He wrote this down and signed the paper, but later refused to transfer the house. She sued him for breach of contract. The issue was whether the agreement to transfer the house was intended to be legally binding. Court held that the agreement having been made when the parties were no longer living together was enforceable at law. N.B:It should be noted that agreements made between wife and husband which are not necessary of a domestic nature are valid and enforceable for example a husband can be a tenant to his wife. However, such agreements are legally binding only when the parties are willing to be legally bound and they expressly state so or where the intention can be construed from the agreement of the parties . If it can however be shown that the transaction had a commercial element, court may find that the intention to create legal relation was present. This was illustrated in the case of Parker V Clarke (1960) 1 ALLER 93; Mrs. Parker was the niece of Mrs. Clarke. An agreement was made that the Parkers would sell their house and live with the Clarke’s who were an elderly couple. They agreed that they would share the bills and the Clarke’s promised to leave the house to them. Mrs. Clarke wrote to the Parkers giving them the details of the expenses and confirming the agreement. The Parkers sold their house and moved in with the Clarkes.Mr. Clarke changed his will leaving the house to the Parkers. Later the couples fell out and the Parkers were asked to leave. They claimed damages for breach of contract. The issue was whether there was an intention to create legal relations between the parties. Court held that the exchange of letters showed that the two couples were serious and the agreement was intended to be legally binding because the Parkers had sold their own home and secondly Mr. Clarke changed his will. Therefore the Parkers were entitled to the damages for breach of contract. 21 Again, in Simpkins v Pays (1955), the defendants, her granddaughter, and the plaintiff agreed that they should submit, in the defendant’s name, a weekly coupon and share the prize. The coupon won £750 which grandma refused to share. It was held that there was an intention to create legal relations and the parties expected to share any prize that was won. Again, the courts will treat family agreements as legally binding when the husband and the wife have separated or divorced or are about to separate, so that the marriage is practically over. Under such circumstances, any agreement entered into by the spouses is presumed to have been intended to be legally binding. QUESTIONS ‘Social agreements are not legally binding’ Do you agree 5. Capacity Section 2 of the contracts Act 2010 laws of Uganda provides for capacity. Section 12 of the contracts Act 2010, is vital. An essential element of a valid contract is that the contracting parties must be competent to contract. The general rule is that all persons have the power to enter into any contract they wish. But special rules apply to minors, mental patient, drunkards, and corporations. Minors / Infants A minor is defined by the contract Act as a person who hasn’t attained the age of 18. Contracts entered into by a minor may be Valid (binding), void or avoidable. Binding contracts Contracts, which are binding on a minor, are contracts for necessaries and contracts of service. Contracts for necessaries Necessities of life are defined under the Sale of Goods Act as goods suitable to the condition in life of an infant and to his actual requirements at the time of sale and delivery. Necessities of life include services and goods, shelter, medical care education and other services like legal advice N.B: The minor is only liable to pay a reasonable price. If the necessaries are sold but not delivered, the minor is not bound. A minor is liable on these contracts of necessities of life.. Therefore minor is not bound to pay for items that are deemed luxurious. Whether a particular commodity falls within the category of ‘’ necessaries’ depends on the circumstances of each case. Thus, while a suit may be an item of necessaries in the case of a minor who comes from a well to do family, it might be an item of luxury to a peasant’s son. The seller must show the minor was not adequately supplied at the time of the contract. This position of the law was stated in the case of Nash vs. Inman (1908); The plaintiff who was a tailor, in the course of 3 months sold 11fancy Waist coats to the value of the 145 pounds to the defendant who was an infant and under graduate of Cambridge. The infant failed to pay and the plaintiff sued for the price. The defendant’s father proved that minor was an infant and was sufficiently supplied with proper clothing’s according to his position. It was held that the defendant wasn’t liable on contracts as there was no evidence to prove that the goods supplied were necessaries of life, which had not been sufficiently supplied to the minor. Therefore, a minor is not liable if he has an adequate supply, even if the supplier did not know this. Contracts of service These are contracts of a beneficial nature to the minor. They are also binding. These include contracts for education, those enabling a minor to earn a living or improve his skills, occupation or profession. The contract must be beneficial to the minor. This is illustrated in Roberts Vs Grey (1913); the infant defendant had agreed to go on a world tour with the plaintiff a professional player, competing against each other in 22 matches .The plaintiff made all the necessary arrangements but the defendant refused. . The plaintiff sued and court observed that the contract was for the infant’s benefit, as he would gain experience and fame by his association with the outstanding player like the plaintiff. However if a contract as a whole is not beneficial to the minor, it will not be binding on him. Voidable contracts Contracts entered into by minors can also be classified as voidable. Voidable means the contract is binding on the minor until he decides to repudiate (reject) it. Therefore voidable contracts are those contracts, which a minor is entitled to repudiate during minority or within a reasonable time after attaining majority age. Apart from the minor’s option to repudiate, a voidable contract is similar to a binding one in that in either case the contract must be beneficial to the minor. But in case of a voidable contract, the subject matter is generally of a permanent or continuing nature. The most outstanding examples of voidable contract are: Lease agreements (here a minor acquires an interest in land) Contracts for the purchase of shares (minor acquires an interest in a company) Contracts of partnerships (minor becomes a partner in a firm) Void Contracts Minors must not enter into the following contracts: Trading contracts and such contract are not binding however beneficial they may be to the infant thus is an infant receive goods on credit and sales them in course of his business for cash he is still not bound to pay for then. In Mechantile limited Union Vs Ball (1937), the defendant an infant hired the plaintiff company lorry. He refused to pay a hire purchase price in breach of contract. The defendant contended that it was for the defendants benefit. Court held that trading contracts whether beneficial or not are not binding on the infant. Loan contracts The same position is in the case of Leslie Vs Sheil. The contract between the two parties involved a loan. The defendant had a requested for a loan which he failed to pay within the prescribed time. When the matter came up in court, court was of the opinion that such contract couldn’t be enforced against the minor as it was prohibited by the law. Contracts to buy luxuries Corporations These are artificial persons recognized by the law. Corporations can take two basic forms. Those created by statute [Statutory corporations or parastetals].These have only powers conferred upon them by the creating statute. Those created under the Companies Act generally referred to as companies. Like natural persons, corporations can enter into valid contracts. They are recognized by the law and are capable of suing or being sued in their own names. They can own property and dispose it off, they can enter into tenancy arrangement and occupy the premises, they can enter into contracts of employment etc. Insane/persons of unsound mind A Contract entered into by an insane persons is not binding unless if at the time of the contracts such person was capable of understanding and appreciating the nature of the contract and the obligations imposed. Drunkards also fall under this category. A contract entered into by a drunkard is voidable but ordinary drunkardness is not sufficient to avoid a contract. It must be proved that at the time of entering into the contracts the party pleading drunkard ness was incapable of understanding the full implications of the transaction. QUESTIONS Explain the concept of contractual capacity of a minor ‘Contracts entered into by drunkards are void’ do you agree? 23 Genuine Consent (Vitiating Factors) Meaning of genuine consent A contract must have been entered into voluntarily and involved a genuine meeting of minds. The agreement may therefore be invalidated by a number of factors e.g. misrepresentation, mistake, duress, undue influence. These factors are known as vitiating factors or elements of a contract. Misrepresentation A misrepresentation is an untrue statement of fact, which induces a party to enter a contract, but which is not itself part of the contract. There must therefore be a statement. Mere silence cannot constitute misrepresentation even when it is obvious that the other party is mistaken as to the facts, subject to some exceptions. Types of misrepresentation Fraudulent misrepresentation occurs when a party makes a statement, which he knows to be false, or has no belief in its truth. In such a case the innocent party may rescind the contract and claim damages for the tort of deceit. This was stated in the case of Negligent misrepresentation may occur where the person making the false statement has no reasonable ground for believing the statement to be true. A person having a duty of care makes the false statement. Innocent misrepresentation occurs when a person who has reasonable ground to believe that the statement is true makes a false statement. In general, a misrepresentation makes a contract voidable rather than void. On discovering the misrepresentation, no matter whether fraudulent, negligent or innocent, the other party may affirm or rescind the contract. Mistake It may be defined as an erroneous belief concerning some thing. Mistake can divided into three types forms. Common mistake A common mistake is made when or where both parties assume some particular state of affairs where as the reality is the other way round. Infact, both parties make exactly the same mistake. Contracts affected by common mistake are void at common law e.g. where parties make a contract believing that there are goods and yet the goods have already perished. This was illustrated in the case of Counturier Vs Hastie; A contact was concluded between the two parties for the sale of corn, which at the time of the contract was believed to be the cargo on the ship. Unknown to both parties the goods had deteriorated in condition and sold on the way to mitigate the loss. Court held that there was no contract concluded because the contract contemplated the existence of the subject matter of something to be sold and bought, but at the time of the contract no such goods existed. Mutual mistake This occurs where in relation to a particular matter one party assumes one thing while the other party assumes a totally different thing, so that they both misunderstands one another. Where each party is mistaken as to the intentions of the other, there is no consensus ad idem and hence no contract. Raffles Vs Wichlaus The parties entered into a contract for he sale of goods to arrive Ex-perless from Bombay, Infact there were two ships called Ex-perless which sailed from Bombay one in October, the other in December. The buyer thought the contract related to the ship sailing in December while the seller thought it was the October ship and therefore the buyer did not take delivery when the October ship arrived. Court held that the buyer was not liable as there was no contract due to mutual mistake. Unilateral mistake 24 A unilateral mistake occurs when just one party is mistaken as to some aspect of the contract, and the other is or is presumed to be aware of this mistake. Examples of unilateral mistake are common in fraud cases where one misrepresents his identity to the other thereby inducing the other party into contracting with him in the false belief that he is contracting with the person whose identity has been given. Duress and undue influence Duress Duress is an illegal threat applied to induce a party to enter a contract, and makes the contract voidable. It is limited to illegal violence or threats of violence to the person of the contracting party. This was illustrated in the case of Cumming v Ince; an old lady was threatened with unlawful confinement in a mental home if she did not transfer certain property rights to one of her relatives. The transfer was set aside because the threat of unlawful imprisonment amounted to duress. In the case of Barton v Armstrong; the defendant threatened to kill the plaintiff if he did not buy his shares. Court set aside the sale because of duress. Undue influence A contract is said to be affected by un due influence if the relationship existing between the parties is such that one of the parties is in position to influence the will of the other and he uses the position to obtain an unfair advantage over the other. Where there is a confidential relationship existing between the parties undue influence is presumed. For example Parent/ Child, Doctor and Patient, Trustee and Beneficially etc. Undue influence renders a contract voidable. QUESTIONS Discuss the various vitiating factors of a contract and their effect on the validity of a contract Discuss the different types of mistake Terms of the Contract Definition of terms These are undertakings or promises made and agreed upon by the parties in the process of negotiating a contract. This does not mean that all the representations made in negotiating a contract form the terms of the contract. It must be a statement of such a nature that if it was not made the contract could not have been concluded. Terms of the contract can either be express or implied. Express terms are those which are specifically put in a contract such that they can be ascertained from the contract without extrinsic evidence. On the other hand implied terms are those which are so obvious that they need not be included in the contract. Such terms are derived from custom or statute and in addition a term may be implied by the court where it is necessary in order to achieve the result which in court’s view the parties obviously intended the 25 contract to have. The Sale of Goods Act Cap 79 laws of Uganda provides for the a number of implied terms in a contract of Sale of Goods unless if expressly excluded by the parties. Terms of the contract can be divided into conditions and warranties. Condition is a vital term of the contract that goes to the root of the contract breach of which entitles the aggrieved party to treat the contract repudiated (as if it was not there) and claim damages for non performance. A warranty on the other hand is a subsidiary obligation which is not so vital such that failure to perform it does not go to the root of the contract. Breach of a warranty is not repudiatory and the plaintiff is only entitled to damages for loss suffered. Whether a term is a condition or a warranty is basically a matter of the court which will be decided on the basis of the commercial importance of the term. Exclusion/Exemption Clauses These are terms or clauses excluding or limiting the liability of one of the parties to a contract in respect of which he would otherwise be held liable in law. Not all exemption clauses are valid. Some are void by legislation for example those which exclude strict liability for death or personal injury from negligence. The application and enforceability of exclusion clauses depends on a number of reasons. Reasonableness of the clause In circumstances where the clause protects the party who has failed to carryout the basic obligation of the contract, the court will not allow him to rely on the exemption clause to escape liability.this was illustrated in the case of Karsale s ltd Vs Wallis; W inspected a car , it was in good condition and agreed to buy it. The agreement contained the following clause “no condition or warranty that the car is road worthy or so to its age, condition or fitness for any purpose is given by the owner or implied her in” When delivery of the car was made, it was in a shocking condition and incapable of self starting. W refused to accept the car. K sued him relying on the exemption clause It was held that as the breach went to the root of the contract it was so unreasonable and could not entitle the plaintiff to rely on it. Reasonable care must be taken to bring it to the attention of the contracting party at the time of the contract. Court requires a person relying on the exclusion clause to show that it was brought to the attention of the other party and that party agreed to it at or before the time when the contract was made, otherwise it will not form part of the agreement. In Olley Vs Marl borough Court Ltd (1949) Husband and wife arrived at a hotel as guests and paid for the room in advance. They went up to the room allocated to them and on one of the walls was a notice, “The proprietors will not hold themselves responsible for articles lost or stolen unless handed to the Manager for safe custody. The wife locked the door and took the key downstairs to the reception desk. A third party picked the key and took some of the property. The defendant sought to rely on the exemption clause. It was held that the contract was concluded at the reception desk and no subsequent notice would affect the plaintiffs rights. The decision could have been different if the parties had visited the Hotel previously and had knowledge of such notice. Spurling vs. Bradshaw (1956) 1WLR 461 Where an exception clause is printed at the back of the receipts it is not valid unless if brought to the attention of the other party. 26 Chapelton Vs. Barry UDC (Urban Development Council) (1940) C hired deck chairs, paid 4 pence and obtained a ticket which he put into a pocket without reading it. It was printed at the back that the defendant will not be liable for any accident or damage arising from the use of the chairs. When C sat on the chair, it collapsed and he was injured. C sued the defendant. It was held that the printed clause at the back of the receipt could not become part of the contract as no reasonable care was taken to bring it to the attention of the contracting party C was entitled to damages. Fraud/misrepresentation Where an exemption clause is contained in the document and a person endorses such contract document he is bound by those clauses contained in it. He cannot rely on the ignorance of the contents of the document unless if he was induced to sign by fraud or misrepresentation. This observation was made in Estrange v Graucob (1934) 2KB 394, Thompson vs Lms Rly (1930) 1KB, Curtis v Chemical clearing dyeing co. (1951). In Curtis, the plaintiff took a dress to the defendant company for cleaning. She was told to sign a receipt she asked why and was told by the defendants that they would not accept any responsibility for damage to the beads and sequins on the dress. In fact the document contained a clause stating that the article is accepted on condition that the company is not liable for any damage however arising. When the dress was collected it was stained and an action for damages was instituted. It was held that the defendant could not rely on the signed document because the sign was obtained by misrepresentation. In Thompson, the plaintiff asked her niece to purchase for her an excursion ticket on front of which were On the back was a notice that the ticket was issued subject to the conditions in the company’s time table which excluded liability for injury however caused. T was injured and claimed damages. It was held that her claim must fail. That she had constructive notice of the conditions which had in courts view; been property communicated to the ordinary passenger. NB: Whether adequate notice relating to exclusion clauses has been given depends on: Type of document e.g. a passenger ticket, it is usually sufficient for the exclusions clause to be prominently set up or referred to the face of the document e.g. Thompson Vs MLS Rly (1930) 1KB 41; However, the situation would be different if the party relying on the exclusion clause was aware of the other parties’ disability e.g. ((illiteracy), where there are no words or the face of the document drawing the attention to the exemption clause, where the words are made illegible by stamp or otherwise, and where the exception clause is hidden in a mass of advertisements. Nature of the exclusion clause. The principle is that the more unusual or least expected, the clause is, the higher will be the notice required to be incorporated. In Crooks v Allen (1870) 59BD 38, it was held that the person relying on a term least expected should make it conspicuous or take other steps to draw attention to it. Timing. The general principle is that an exclusion clause will be incorporated in the contract if notice of it is given before or at the time of the contract of olley v Marlborough Ltd. QUESTIONS Define an exclusion clause Distinguish between an implied and express term Distinguish between condition and a warranty Discharge of Contract 27 Discharge of a contract means that the parties are freed from their mutual obligations. A contract can be discharged in various ways: Performance This is where both parties have performed the obligations, which the contract placed upon them. Performance must be completed i.e. it must be in accordance with the terms of the contract if the Performance is incomplete (contrary to the terms/the defaulting party may be sued for damages. At common law, where performance is incomplete such party in default is not entitled to any payment. Discharge by agreement Where a contract is still executory, i.e.Where each of the parties is yet to perform his contractual obligation, the parties may mutually agree to release each other from their contractual obligation. Each party’s promise to release the other is consideration for the other party’s promise to release him. . Discharge by frustration. A contract is said to be frustrated if an event occurs which brings its further fulfilment to an abrupt end, and upon the occurance the parties are discharged. But the doctrine of frustration only relates to the future.This mean that the parties are discharged from their future obligation under the contract but remain liable for whatever rights that may have accrued before the frustration , although the parties are both excused from further performance of the contract. It is difficult to determine the frustrating events but some examples are given below: Destruction of Subject Matter Taylor v. Caldwell (1862) The defendant let a building to the plaintiff for holding concerts on specified days. Before the concerts could be held the music hall was accidentally des troyed by fire. A suit was filed for breach of contract and court held that the action could not be maintained. Death or Incapacity Just as the destruction of the subject matter of the contract terminates it, the death or serious indisposition of a party whose personal services were contemplated by the contract will similarly terminate it. Thus, if A contracts to stage a series of shows during the month of June- September but is in May sentences to imprisonment for one year, or becomes insane permanently or for a substantial part of the period in question, the contract will similarly be discharged by frustration- the frustrating event being constituted by the imprisonment or insanity. Supervening illegality A contract is also frustrated if, after its formation, a circumstance arises which renders its further performance illegal. There is said to be supervening illegality, which operates as a frustrating event e.g. change in the law of the country. Discharge by breach Breach of contract by a party thereto is also a method of discharge of a contract, because “breach” also brings to an end the obligations created by by a contract on the part of each of the parties. Of course the aggrieved party i.e the party not at fault can sue for damanges for breach of contract as per law but the contract as such stands terminated. Acontract is said to be breached when its terms are broken. Failure to honour ones contractual obligation is what constitutes a breach of contract. buyer has two options; he may choose to wait for the date of performance to come before taking any action against the seller. 28 Discharge by operation of law Acontract may be discharged by operation of law in certain cases . Some important instances are as under: lapse of time If a contract is made for a specific period then after the expiry of that period the contract is discharged e.g. partnership deed employment contact etc. Death The death of either party to a contract discharges the contract where personal services are involved. Substitution. If a contract is substituted with another contract then the first contract is discharged. Bankruptcy When a person becomes bankrupt, all his rights and obligations pass to his trustees in bankruptcy.But a stustee is not liable on contracts of personal services to be rendered by the bankrupt. Remedies for breach of contract Whenever there is a breach of contract,the injured party becomes entitled for some remedies. These remedies are: Damages Quantum meruit Specific performance Injunction Rescission Damages Damages are monitary compasation allowed to the injured party of the loss or Injury suffered by him as a result of the breach of contract. The fundermantal principle underlying damages is not punishment but compensation. By awarding damages the court aims to put the injured party into the position in which he would have been ,had there been performance and not breach , and not punish the defaulter. As a general rule compesation must be commensurate with the injury or loss sustained, arising naturally from the breach. If actual loss is not proved , no damages will be awarded to the other party. The plaintiff cannot claim damages for loss which is attributable to his failure to mitigate. Quantum Meruit The third remedy for a breach of contract available of an inured party against the guilty party is to file a suit upon quantum meruit. The phrase quantum merit literally means, “as much as is earned” or “ in proportion to the work done. The aggrieved party may file a suit upon quantum merit and may claim payment in proportion to work done or goods supplied. Specific Performance This is an equitable remedy. Specific performance means the actual carrying out of the contract as agreed. Under certain circumstances an aggrieved party may file a suit for specific performance, i.e. for a decree by the court directing the defendant to actually perform the promise that he has made. Injunction Injunction is an order of a court restraining a person from doing a particular act. It is a mode of securing the specific performance of the negative terms of the contract. To put it differently, where a party is in breach of a negative term of the contract (i.e. where he is doing something which he promised not to do), the court may by issuing an injunction, restrain him from doing , what he promised not to do. Thus 29 “injunction” is a preventive relief. It is particularly appropriate in cases of “anticipatory breach of contract” where damages would not be an adequate relief. Rescission When there is a breach of contract by one party, the other may rescind the contract and need not perform his part of obligation. Such innocent party may sit quietly at home if he decides not to take any legal action against the guilty party. But in case the aggrieved party intends to sue the guilty party for damages for breach of contract, he has to file a suit for rescission of the contract. When the court grants rescission, the aggrieved party is freed from all his obligations under the contract; and becomes entitled to compensation for any damage, which he has sustained through the non-fulfillment of the contract. QUESTION ‘Once a valid contract is made, it cannot be terminated under any circumstances’ Discuss 30