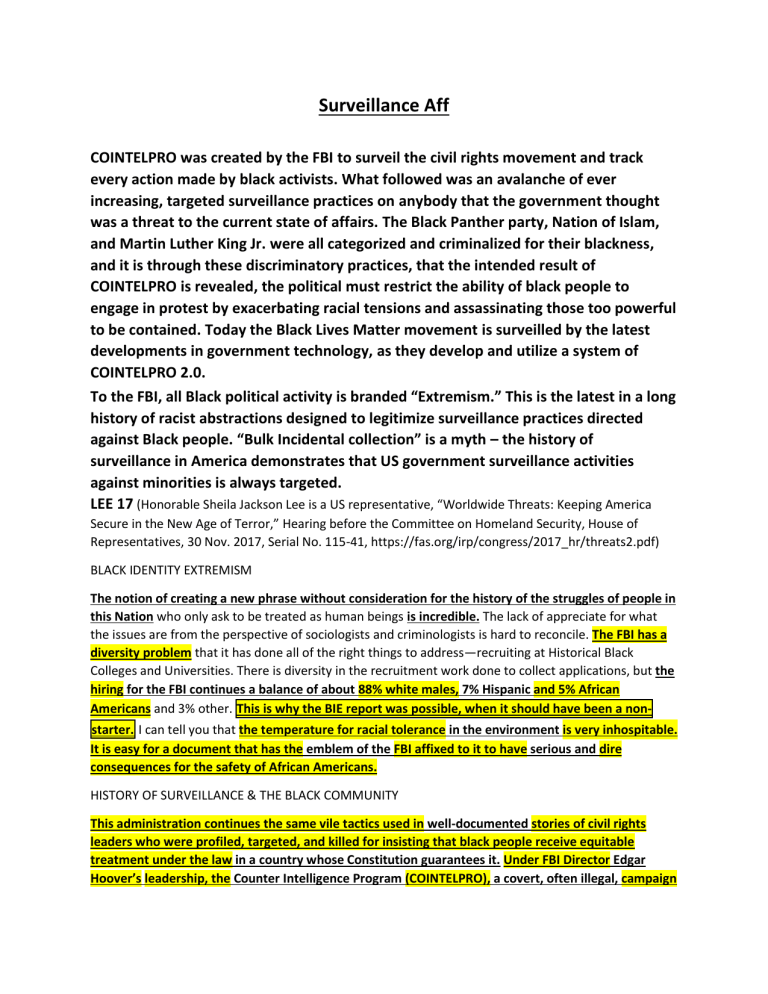

Surveillance Aff COINTELPRO was created by the FBI to surveil the civil rights movement and track every action made by black activists. What followed was an avalanche of ever increasing, targeted surveillance practices on anybody that the government thought was a threat to the current state of affairs. The Black Panther party, Nation of Islam, and Martin Luther King Jr. were all categorized and criminalized for their blackness, and it is through these discriminatory practices, that the intended result of COINTELPRO is revealed, the political must restrict the ability of black people to engage in protest by exacerbating racial tensions and assassinating those too powerful to be contained. Today the Black Lives Matter movement is surveilled by the latest developments in government technology, as they develop and utilize a system of COINTELPRO 2.0. To the FBI, all Black political activity is branded “Extremism.” This is the latest in a long history of racist abstractions designed to legitimize surveillance practices directed against Black people. “Bulk Incidental collection” is a myth – the history of surveillance in America demonstrates that US government surveillance activities against minorities is always targeted. LEE 17 (Honorable Sheila Jackson Lee is a US representative, “Worldwide Threats: Keeping America Secure in the New Age of Terror,” Hearing before the Committee on Homeland Security, House of Representatives, 30 Nov. 2017, Serial No. 115-41, https://fas.org/irp/congress/2017_hr/threats2.pdf) BLACK IDENTITY EXTREMISM The notion of creating a new phrase without consideration for the history of the struggles of people in this Nation who only ask to be treated as human beings is incredible. The lack of appreciate for what the issues are from the perspective of sociologists and criminologists is hard to reconcile. The FBI has a diversity problem that it has done all of the right things to address—recruiting at Historical Black Colleges and Universities. There is diversity in the recruitment work done to collect applications, but the hiring for the FBI continues a balance of about 88% white males, 7% Hispanic and 5% African Americans and 3% other. This is why the BIE report was possible, when it should have been a nonstarter. I can tell you that the temperature for racial tolerance in the environment is very inhospitable. It is easy for a document that has the emblem of the FBI affixed to it to have serious and dire consequences for the safety of African Americans. HISTORY OF SURVEILLANCE & THE BLACK COMMUNITY This administration continues the same vile tactics used in well-documented stories of civil rights leaders who were profiled, targeted, and killed for insisting that black people receive equitable treatment under the law in a country whose Constitution guarantees it. Under FBI Director Edgar Hoover’s leadership, the Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO), a covert, often illegal, campaign was mounted to break up the civil rights movement and ‘‘neutralize’’ activists they perceived as threatening. COINTELPRO was used to surveil and discredit civil rights activists, members of the Black Panther Party and any major advocates for the rights of black people in our Nation’s history. COINTELPRO allowed the FBI to falsify letters in an effort to blackmail Martin Luther King Jr. into silence. This was such a disgraceful period in our Nation’s history that our recent FBI Director, James Comey, kept a copy of a 1963 order authorizing Hoover to conduct round-the-clock surveillance of Martin Luther King Jr. on his desk as a reminder of Hoover’s abuses. The FBI’s dedicated surveillance of black activists follows a long history of the U.S. Government aggressively monitoring protest movements and working to disrupt civil rights groups, but the scrutiny of African Americans by a domestic terrorism unit was particularly alarming to some free-speech campaigners. FBI: Black Lives Matter and the Black Identity Extremists Report Today the FBI continues its once intrusive, abhorrent, and illegal targeting of black activists by labeling the Black Lives Matter movement as Black Identity Extremism. We know that the Department of Homeland Security has been surveilling Black Lives Matter activists since 2014, but there’s no way to know what’s next. With this recent report, the FBI has legitimized the idea that black activism is a threat and should be treated accordingly—with violent force. Despite Charlottesville and all the other harms inflicted by emboldened white nationalists, the FBI has instead, chosen to target a group of American citizens whom merely decry the injustice seen and felt throughout their communities. Despite numerous unarmed black individuals, particularly, young black men that are disproportionately the victims of police shootings, the FBI would like us to believe this is not a reality. Instead, the FBI’s report claims there is a danger in black activism by asserting that violence inflicted on black people at the hands of police is ‘‘perceived’’ or ‘‘alleged,’’ not real. This month the Congressional Black Caucus has written to the FBI director, Christopher Wray, to express our concern over the recent ‘‘Intelligence Assessment’’ report. We have requested a briefing on both the origins of its research and the FBI’s next intended step based on its findings. No response as of date. We should be allowed to exercise our Constitutional and fundamental rights of free speech. We should not be restricted and criminalized when we demand that those we elect to office exercise justice and fairness. This FBI report will further inflame an already damaged police/community relation under the leadership of Attorney General Jeff Sessions. Sessions has dismantled all the safeguards installed under Attorney General Holder’s leadership, thus, returning our justice system to the broken system under Ashcroft. Sessions has unleashed a merciless approach to ‘‘all’’ crimes including low-level drug-related cases, and demands that his attorneys prosecute every case to the fullest extent of the law. In doing so, Sessions has taken away any prosecutorial discretion once available to prosecutors throughout our justice system under U.S. law. The FBI in this Trump administration has returned to the era of Director Edgar Hoover, in their unleashing of this damaging, discriminative, and unconstitutional COINTELPRO 2.0. With these lethal forms of attacks on the African American community from both the DOJ and the FBI, where is justice? Beginning in the 1960’s Republican politicians began to rally political support among the Democrat controlled South by playing on racial fears through a rhetoric of Law and Order which framed Black political activity as street crime. This model was transposed into a form of racial securitization during the Clinton regime of “workfare” because it adapted from a logic of rehabilitation to a model of prevention. This securitization is accelerated by the War on Drugs, a racialized and militarized exercise of government terrorism of Black communities. The mass incarceration of Black people is the inevitable result of the expansion of surveillance and is directly tied to the regular police killings of Black people. KUNDNANI and KUMAR 15 (Arun Kundnani teaches at NYU and Deepa Kumar is an associate professor of Media Studies and Middle East Studies at Rutgers University, “Race, Surveillance, and Empire,” International Socialist Review, Issue #96, https://isreview.org/issue/96/race-surveillance-andempire) The law and order rhetoric that was used to mobilize support for this project of securitization was racially coded, associating Black protest and rebellion with fears of street crime. The possibilities of such an approach had been demonstrated in the 1968 election, when both the Republican candidate Richard Nixon and the independent segregationist George Wallace had made law and order a central theme of their campaigns. It became apparent that Republicans could cleave Southern whites away from the Democratic Party through tough-on-crime rhetoric that played on racial fears. The Southern Strategy, as it would be called, tapped into anxieties among working-class whites that the civil rights reforms of the 1960s would lead to them competing with Blacks for jobs, housing, and schools. With the transformation of the welfare state into a security state, its embedding in everyday life was not undone but diverted to different purposes. Social services were reorganized into instruments of surveillance. Public aid became increasingly conditional on upholding certain behavioral norms that were to be measured and supervised by the state, implying its increasing intrusion into the lives of the poor—culminating in the “workfare” regimes of the Clinton administration.50 In this context, a new model of crime control came into being. In earlier decades, criminologists had focused on the process of rehabilitation; those who committed crimes were to be helped to return to society. While the actual implementation of this policy was uneven, by the 1970s, this model went out of fashion. In its place, a new “preventive” model of crime control became the norm, which was based on gathering information about groups to assess the “risk” they posed. Rather than wait for the perpetrator to commit a crime, risk assessment methods called for new forms of “preventive surveillance,” in which whole groups of people seen as dangerous were subject to observation, identification, and classification.51 The War on Drugs—launched by President Reagan in 1982—dramatically accelerated the process of racial securitization. Michelle Alexander notes that At the time he declared this new war, less than 2 percent of the American public viewed drugs as the most important issue facing the nation. This fact was no deterrent to Reagan, for the drug war from the outset had little to do with public concern about drugs and much to do with public concern about race. By waging a war on drug users and dealers, Reagan made good on his promise to crack down on the racially defined “others”—the undeserving.52 Operation Hammer, carried out by the Los Angeles Police Department in 1988, illustrates how racialized surveillance was central to the War on Drugs. It involved hundreds of officers in combat gear sweeping through the South Central area of the city over a period of several weeks, making 1,453 arrests, mostly for teenage curfew violations, disorderly conduct, and minor traffic offenses. Ninety percent were released without charge but the thousands of young Black people who were stopped and processed in mobile booking centers had their names entered onto the “gang register” database, which soon contained the details of half of the Black youths of Los Angeles. Entry to the database rested on such supposed indicators of gang membership as high-five handshakes and wearing red shoelaces. Officials compared the Black gangs they were supposedly targeting to the National Liberation Front in Vietnam and the “murderous militias of Beirut,” signaling the blurring of boundaries between civilian policing and military force, and between domestic racism and overseas imperialism.53 In the twelve years leading up to 1993, the rate of incarceration of Black Americans tripled,54 establishing the system of mass incarceration that Michelle Alexander refers to as the new Jim Crow.55 And yet those in prison were only a quarter of those subject to supervision by the criminal justice system, with its attendant mechanisms of routine surveillance and “intermediate sanctions,” such as house arrests, boot camps, intensive supervision, day reporting, community service, and electronic tagging. Criminal records databases, which are easily accessible to potential employers, now hold files on around one-third of the adult male population.56 Alice Goffman has written of the ways that mass incarceration is not just a matter of imprisonment itself but also the systems of policing and surveillance that track young Black men and label them as would-be criminals before and after their time in prison. From stops on the street to probation meetings, these systems, she says, have transformed poor Black neighborhoods into communities of suspects and fugitives. A climate of fear and suspicion pervades everyday life, and many residents live with the daily concern that the authorities will seize them and take them away.57 A predictable outcome of such systems of classification and criminalization is the routine racist violence carried out by police forces and the regular occurrences of police killings of Black people, such as Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, 2014. Surveillance debates are framed within a myth of race neutrality – the privacy rights of white America are given precedence over the real violence inflicted on marginalized communities. While our communities are excused and protected Black communities are targeted wholesale. Every time we participate in this whitewashing of surveillance we reinforce racism. KUNDNANI and KUMAR 15 (Arun Kundnani teaches at NYU and Deepa Kumar is an associate professor of Media Studies and Middle East Studies at Rutgers University, “Race, Surveillance, and Empire,” International Socialist Review, Issue #96, https://isreview.org/issue/96/race-surveillance-andempire) Today, we are once again in a period of revelation, concern, and debate on national security surveillance. Yet if real change is to be brought about, the racial history of surveillance will need to be fully confronted—or opposition to surveillance will once again be easily defeated by racial security narratives. The significance of the Snowden leaks is that they have laid out the depth of the NSA’s mass surveillance with the kind of proof that only an insider can have. The result has been a generalized level of alarm as people have become aware of how intrusive surveillance is in our society, but that alarm remains constrained within a public debate that is highly abstract, legalistic, and centered on the privacy rights of the white middle class. On the one hand, most civil liberties advocates are focused on the technical details of potential legal reforms and new oversight mechanisms to safeguard privacy. Such initiatives are likely to bring little change because they fail to confront the racist and imperialist core of the surveillance system. On the other hand, most technologists believe the problem of government surveillance can be fixed simply by using better encryption tools. While encryption tools are useful in increasing the resources that a government agency would need to monitor an individual, they do nothing to unravel the larger surveillance apparatus. Meanwhile, executives of US tech corporations express concerns about loss of sales to foreign customers concerned about the privacy of data. In Washington and Silicon Valley, what should be a debate about basic political freedoms is simply a question of corporate profits.69 Another and perhaps deeper problem is the use of images of state surveillance that do not adequately fit the current situation—such as George Orwell’s discussion of totalitarian surveillance. Edward Snowden himself remarked that Orwell warned us of the dangers of the type of government surveillance we face today.70 Reference to Orwell’s 1984 has been widespread in the current debate; indeed, sales of the book were said to have soared following Snowden’s revelations.71 The argument that digital surveillance is a new form of Big Brother is, on one level, supported by the evidence. For those in certain targeted groups—Muslims, left-wing campaigners, radical journalists—state surveillance certainly looks Orwellian. But this level of scrutiny is not faced by the general public. The picture of surveillance today is therefore quite different from the classic images of surveillance that we find in Orwell’s 1984, which assumes an undifferentiated mass population subject to government control. What we have instead today in the United States is total surveillance, not on everyone, but on very specific groups of people, defined by their race, religion, or political ideology: people that NSA officials refer to as the “bad guys.” In March 2014, Rick Ledgett, deputy director of the NSA, told an audience: “Contrary to some of the stuff that’s been printed, we don’t sit there and grind out metadata profiles of average people. If you’re not connected to one of those valid intelligence targets, you are not of interest to us.”72 In the national security world, “connected to” can be the basis for targeting a whole racial or political community so, even assuming the accuracy of this comment, it points to the ways that national security surveillance can draw entire communities into its web, while reassuring “average people” (code for the normative white middle class) that they are not to be troubled. In the eyes of the national security state, this average person must also express no political views critical of the status quo. Better oversight of the sprawling national security apparatus and greater use of encryption in digital communication should be welcomed. But by themselves these are likely to do little more than reassure technologists, while racialized populations and political dissenters continue to experience massive surveillance. This is why the most effective challenges to the national security state have come not from legal reformers or technologists but from grassroots campaigning by the racialized groups most affected. In New York, the campaign against the NYPD’s surveillance of Muslims has drawn its strength from building alliances with other groups affected by racial profiling: Latinos and Blacks who suffer from hugely disproportionate rates of stop and frisk. In California’s Bay Area, a campaign against a Department of Homeland Security-funded Domain Awareness Center was successful because various constituencies were able to unite on the issue, including homeless people, the poor, Muslims, and Blacks. Similarly, a demographics unit planned by the Los Angeles Police Department, which would have profiled communities on the basis of race and religion, was shut down after a campaign that united various groups defined by race and class. The lesson here is that, while the national security state aims to create fear and to divide people, activists can organize and build alliances across race lines to overcome that fear. To the extent that the national security state has targeted Occupy, the antiwar movement, environmental rights activists, radical journalists and campaigners, and whistleblowers, these groups have gravitated towards opposition to the national security state. But understanding the centrality of race and empire to national security surveillance means finding a basis for unity across different groups who experience similar kinds of policing: Muslim, Latino/a, Asian, Black, and white dissidents and radicals. It is on such a basis that we can see the beginnings of an effective multiracial opposition to the surveillance state and empire. Our method is to become traitors exposing the history of surveillance to confront our complicity with whiteness. Whiteness creates anti-black racism by perpetuating narratives of race blindness, which protect the white population from uncomfortable encounters with their complicity in systems of oppression. This racial contract is premised on a network of surveillance that renders Black people hypervisible. Against this racial violence we create a countergaze which forces white people to accept accountability for their role in the creation and proliferation of whiteness, an act of traitorship which is a necessary prerequisite to any constructive engagement in racial conversations. JUNGKUNZ and WHITE 13 (Vincent Jungkunz and Julie White are both scholars at Ohio University, “Ignorance, Innocence, and Democratic Responsibility: Seeing Race, Hearing Racism,” The Journal of Politics, Vol. 75, No. 2, April 19, pg. 436-46, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.1017/s0022381613000121.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ab77d697547 5e714854a261154e4ce952) In his Seeing Like a State, James Scott argues that the modern state is a vision state, a state whose mechanisms and techniques for seeing and rendering subjects legible are unparalleled. The modern state, Scott claims, makes ‘‘a society legible to arrange the populations in ways that simplified the classic state functions’’ (1998, 2).1 In what follows, we will argue that the making and maintenance of white privilege in the contemporary context requires that subjects be made legible, that is visible, as racialized subjects. The practices of surveillance envision raced bodies, properly ‘‘arranging them,’’ and identifying misplaced or out of place embodiments—the black body in white space as threat, the white body in black space as threatened. It is through these practices of targeted surveillance that we come to know race and know where race belongs. The making and maintenance of white privilege is accomplished through the seeing state and its blind spots; together these naturalize and stabilize racial ordering. Such a vision of racial orderings refuses democratic renegotiations. Democratic renegotiations, we argue, would require that, like Scott, we recognize ‘‘seeing’’ as a discursive practice of actively envisioning and challenge the ways in which these envisionings reflect the gaze of the privileged and the powerful; the way in which it is a white gaze. We then ask, given the actively and politically constructed nature of these envisionings, are there more responsible and less responsible ways to ‘‘see’’ and so to ‘‘know’’ the social world? Is there a responsibility to know the unnamed political system of white supremacy (Mills 1997, 1), even if ‘‘we’’ don’t at present ‘‘see’’ it? What does the political process of coming to know entail? In the pursuit of a racially just democracy, we argue that holding each other accountable—even in the face of claims ‘‘not to know,’’ claims to ignorance, and implicitly, innocence—is a critical democratic practice. Especially because race and visibility are, in this contemporary U.S. context, inherently fused together—race being the visible identity par excellence (See Alcoff 2006), it might be that a move away from centering vision and visibility as the means through which we understand and manage race and racism is vital for attempts to begin undoing white supremacy and its built-in blindnesses. We argue that racially responsible ‘‘knowing’’ requires moving beyond seeing race (as objective fixed identity and demographic variable) to listening for, and to hearing, racism (as oppressive practice and lived experience). ‘‘Hearing’’ as a practice, one made possible by a ‘‘silent yielding’’ (see Jungkunz 2011) on the part of whites to the testimonies of racial others, brings together the possibility of whites coming to recognize racism while simultaneously embodying as a practice a critical political shift in authority. In so doing, white ignorance is challenged not just through reauthoring the story of race—telling a different, and perhaps more complete, truth about racism’s creation of race, a story told from a racially marginal perspective—but also reauthorizing the terms of legitimate speaking. Specifically, democratic renegotiations of the meaning of race require receptive listening:2 the silent yielding of whites to the testimonials of racialized others as both an epistemologically critical practice and a politically transformative one. Interlude: The Scene and the Seeing of the Crime In a neoliberal socioeconomic and political context, it seems a rather straightforward violation, the one experienced by an esteemed Harvard professor in 2009 in Cambridge, Massachusetts: The over-reaching arm of the state once again threatens private property and individual freedom. A man is arrested for breaking into his own house. We could so readily have anticipated the response of right-wing talk radio: ‘‘His home, his castle, HIS PROPERTY and HIS FREEDOM!’’ And beyond Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh we could expect even liberals to participate in the outcry about overly zealous police officers. Voices from both the left and right in concert together are outraged by the violations experienced by an innocent man entering his OWN residence. Shouldn’t we have expected such reactions? Blackness dashes these expectations of outrage even when its address is Cambridge, Massachusetts. This is the dysfunctional and effective world of white privilege. The Gates controversy began with a moment of vision, a citizenly envisioning: A passerby (a white woman) spots Professor Gates and his driver (both African American men) attempting to push open the stuck front door to the Professor’s house. This white subject sees and mobilizes a (white) surveillance posture; unsure whether the Professor is an intruder or the homeowner, she is suspicious enough to call 911.3 The gaze assesses Gates himself as unapproachable. So, the passerby does not engage, does not ask: Is everything o.k.? Is your door stuck? Can I give you a hand? Do you live there? Are you visiting? Are you working on the house? We can imagine this as a hailing moment (Althusser 1971). First, the 911 caller, and then the infamous Sergeant James Crowley, found themselves hailed via white racial consciousness, by a truth regime about black men. Two black men (in no apparent hurry, nor in any posture of secrecy—though viewed through the lens of a white gaze these aspects were not attended to) were struggling with the door to a house in her neighborhood. That’s it. Law (and the criminality it implies) was mobilized. Charles Ogletree, Gates’s attorney and author of a book recounting the events of that day, provides evidence of at least three aspects of the case that suggest the coincidence of the authority of the state with the white gaze. First, while the 911caller was suspicious, she was also acknowledging to the dispatcher that she might be reporting the home-owner struggling with the door to his own property. Yet neither the caller nor the police adopted an open or inquisitive posture toward Gates. Second, it is indisputable that prior to the arrest Gates did provide Sgt. Crowley with two pieces of identification, his Harvard identification card and his Massachusetts driver’s license, both of which identified the residence as his home. Yet Crowley remained skeptical that Professor Gates was ‘‘who he claimed to be and was where he belonged’’ (Ogletree 2010, 33). Finally, the nature of the charge against Gates, the basis for his arrest, the statute entitled ‘‘Crimes against Chastity, Morality, Decency, and Good Order,’’ does not identify any of the behaviors Gates engaged in either in his home or on his porch. Yet arguably the very presence of a black man on the Harvard campus challenges ‘‘good order’’ when viewed through the gaze of the white state.4 Thus, what should have and could have been an open and closed case of offensive home invasion by overly zealous big government becomes, seen through the lens of race, reasonable and just action by the police. In the end, the arresting officer received much praise and ultimately some sympathy because he was accused of being a racist. Many whites expressed concern about Professor Gates ‘‘playing the race card,’’ and the President himself had to retract a statement about the stupidity of the police actions.5 The fact that the police officer both refused to give Gates his name and badge number and refused to apologize speaks volumes about the power and privilege of official whiteness. These privileges are protected and perpetuated through a seeing eye, a white gaze that actively shapes while pretending merely to passively reflect a racial topography. Justice Is Blind and So Are ‘‘We’’ ‘‘Knowing’’ is central to the practice of consolidating responsibility; with the determination that ‘‘he didn’t know any better,’’ we are suggesting that not knowing limits individual culpability. ‘‘He’’ did something, something hurtful, and yet, due to ignorance, is neither personally dogged by responsibility nor held socially accountable. ‘‘Ignorance is bliss’’—that is, the bliss of refusing knowledge and, therefore, accountability. One of the primary ways through which we both imagine and communicate a knowledge, ignorance, and responsibility nexus is ‘‘vision,’’ both metaphorically and materially.6 Yet, while visual metaphors are pervasive in epistemological discussions—as ways of discussing both what we ‘‘see’’ as true and what we are ‘‘blind’’ to—ultimately they undermine the thicker and more politically useful conception of responsibility democracy requires. Given the cultural-political milieus involved, many ordinary white subjects have been rendered blind to racial injustice and racist actions. Thus, when the white gaze ‘‘sees’’ nonwhite citizens in the least habitable areas of a city, it simply observes a population in its place, where it belongs.7 Not an unjust racial politics but undeserving races.8 For this ‘‘observable social pattern’’ to be about injustice, we have to recognize the possibility that there is a different story to tell about belonging. The recognition that it is a story of white privilege that constructs our envisionings requires skepticism about ‘‘what we (whites) see with our own two eyes.’’ But privilege is maintained exactly because it resists such skepticism, because it objectifies white envisionings, putting them outside or beyond alternative narrations, denying or foreclosing the space for counterstories that might prompt different envisionings to emerge.9 Mills identifies the stability of the white gaze as the pervasiveness of an ‘‘epistemology of ignorance.’’ This configuration of responsibility can quite easily be manipulated by whites as a defensive posture that shields them from accusations of racism. However, many ‘‘well-intentioned’’ whites could, on a more appropriate model of the relationship between vision, knowledge, and responsibility, be understood as actively employing blindness. The Epistemology of Ignorance: Blindness, Whiteness, and Irresponsibility Transparency, the tendency of Whites to remain blind to the racialized aspects of that identity, is omnipresent. (Lopez 1996, 157) Whiteness wants to see everything except its own operations. (Fiske 1998, 84) As McIntosh observes, ‘‘As a white person, I realized I had been taught about racism as something which puts others at a disadvantage, but had been taught not to see one of its corollary aspects, white privilege, which puts me at an advantage’’ (2004, 104).10 Most whites do not see themselves, or their lives, as raced in the way they view the lives of ‘‘nonwhites’’ as raced. Lopez fills out the blindnesses of white privilege in this way: Indeed, for many Whites their racial identity becomes uppermost in their mind only when they find themselves in the company of large numbers of non-Whites, and then it does so in the form of a supposed vulnerability to non-White violence, rendering Whiteness in the eyes of many Whites not a privileged status but a victimized one. Nevertheless, the infrequency with which Whites have to think about race is a direct result of how infrequently Whites in fact are racially victimized. (1996, 158) Particular blind spots and alternative visions are critical to the maintenance of white privilege. Blindness on the part of whites—especially the claim, descriptive as well as normative, not to ‘‘see’’ race—becomes a powerful disavowal of responsibility where seeing is knowing, and knowing is taken to precede fair conditions of accountability. When Mills speaks of an epistemology of ignorance that maintains racial divisions, or what he calls a ‘‘Racial Contract’’ that divides the world into ‘‘persons’’ and ‘‘sub-persons,’’ he connects this ignorance to the perpetuation of white privilege. In this context, whites are socialized, legalized, and politicized not to think too much about the socially constructed nature of their privilege or the devastating costs to others. Hochschild captures Mills’s argument in The Racial Contract: Fish don’t see water, men don’t see patriarchy, and white philosophers don’t see white supremacy. We can do little about fish. Carole Pateman and others have made the sexual contract visible for those who care to look. Now Charles Mills has made it equally clear how whites dominate people of color, even (or especially) when they have no such intention. He asks whites not to feel guilty, but rather to do something much more difficult—understand and take responsibility for a structure which they did not create but still benefit from. (Mills 1997, Front Matter) On her account, blindness, not seeing, has implications for intentionality and so for moral accountability. If one cannot see what one is doing, and what one is doing is dominating another, one surely could not be assumed to have intended as much. On traditional models, this lack of vision and intentionality is enough to mitigate responsibility.11 Hochschild is not jettisoning the connection between intention and responsibility per se. She is highlighting the intervening variable of sight, or vision, as a way to assess responsibility for current states of injury. Ultimately, when whites are ‘‘shown the light,’’ they confront a more authentic choice situation. Seeing, knowledge, and responsibility converge in Hochschild’s assessment of Mills. Mills states: The requirements of ‘‘objective’’ cognition, factual and moral, in a racial polity are in a sense more demanding in that officially sanctioned reality is divergent from actual reality. So here, it could be said, one has an agreement to misinterpret the world. One has to learn to see the world wrongly, but with the assurance that this set of mistaken perceptions will be validated by white epistemic authority, whether religious or secular. (1997, 18) While Mills’ racial contract expressly values objective vision, it requires blindness to white privilege, and this blindness is made possible through ‘‘an agreement to misinterpret the world’’ through representations of reality that obscure the presence and meaning of racist practices and ideas. Official proclamations, political communications, and legal apparatuses, a world Marx would call ‘‘politically emancipated,’’ celebrates universalism. Rather than officialdom serving as a check on this interpretation, it ultimately perpetuates it. For ‘‘seeing like a state’’ is seeing with a white gaze, while simultaneously rendering invisible the processes of constructing and directing this gaze. In a social context in which Michael Richards (aka Seinfeld’s ‘‘Kramer’’) performs a blatantly racist tirade and still feels he can claim he just didn’t know what he was doing, where college students ‘‘celebrate’’ Martin Luther King Day with racist parties in which they wear blackface and perform racial stereotypes, it seems maybe more vital than ever to ask whether this invisibility, this ignorance, is willful and therefore irresponsible.12 Richards claimed on the David Letterman Show that the ‘‘crazy’’ thing about his outburst was that he is not a racist, and the students involved in these racist parties also claimed that they did not know they were being racist or offensive. While one might question the authenticity of such claims, Mills’ theorizing of racial ignorance gives some credence to this paradox. Yet Mills insists, To understand the actual moral practice of past and present, one needs not merely the standard abstract discussions of, say, the conflicts in people’s consciences between self-interest and empathy with others but a frank appreciation of how the Racial Contract creates a racialized moral psychology. Whites will then act in racist ways while thinking of themselves as acting morally. In other words, they will experience genuine cognitive difficulties in recognizing certain behavior patterns as racist, so that quite apart from questions of motivation and bad faith they will be morally handicapped simply from the conceptual point of view in seeing and doing the right thing. (1997, 93) When recent controversies surrounding racist speech (Mel Gibson, Michael Richards, Don Imus) have occurred, whites have dominated the debates about whether a given speech act is racist. Remarkably, the ‘‘white epistemic authorities’’ Mills refers to typically offer explanations beyond racism to account for racist language—Michael Richards was ‘‘not really racist,’’ he was just heckled or intoxicated. It is seeing race through this lens and the parallel silence regarding white privilege that produces the ‘‘I didn’t know that was racist’’ explanation qua excuse. A framing of ignorance avoids assessing responsibility and in so doing keeps racism and its harms out of focus. Mills seems to attribute a sensitive moral compass to white subjects: One could say then, as a general rule, that white misunderstanding, misrepresentation, evasion, and self-deception on matters related to race are among the most pervasive mental phenomena of the past few hundred years, a cognitive and moral economy psychically required for conquest, colonization, and enslavement. And these phenomena are in no way accidental, but prescribed by the terms of the Racial Contract, which requires a certain schedule of structured blindnesses and opacities in order to establish and maintain the white polity. (1997, 19) For Mills, white misunderstanding and blindnesses explain complicity with racial exploitation. Whites, on this account, could not stand to look at themselves in the proverbial mirror without fooling themselves into believing that they are upstanding moral agents. The ‘‘Racial Contract,’’ Mills concludes, ‘‘thus places itself within the sensible mainstream of moral theory by not holding people responsible for what they cannot help’’ (1997, 126). The configuration of helplessness with ignorance and whiteness can be a devastating defense of the status quo. The ‘‘blindnesses’’ could alternatively be understood as active techniques of denial, techniques that perpetuate white privilege. Cohen’s work on denial seems helpful here, for as he notes, ‘‘turning a blind eye’’ is often about keeping certain facts ‘‘conveniently out of sight:’’ There are two modes of evading the realities of personal and mass suffering. First, turning a blind eye—keeping facts conveniently out of sight, allowing something to be both known and not known. Such methods can be highly pathological but nevertheless ‘reflect a respect and fear of the truth and it is this fear which leads to the collusion and cover-up.’ Turning a blind eye is a social motion. We have access to enough facts about human suffering, but avoid drawing their disquieting implications. We cannot face them all the time. (2001, 34) Even a slight shift to the language of evasion helps us better situate responsibility with white subjects within racialized polities. Mills, and others including Hochschild, are contributing to the construction of a link between vision, knowledge, intentionality, and responsibility that avoids accountability of white subjects for their privilege. When taken with her other comments, ‘‘for those who care to look’’ does indicate Hochschild’s recognition that care, intentionality, and will are part and parcel of efforts to deal directly with oppression. Again, the metaphor is vision, and within that it is caring to look that becomes important. Ignorance may be a consequence of a failure to see but we are still left with a kind of responsibility: ‘‘the responsibility to care to look.’’ We can be held accountable for our blindnesses. Visions that Perpetuate Racism Responsibility requires more than addressing our blind spots. It requires a racially critical skepticism toward what we see as well. One of the key problems with a vision-knowledge-responsibility configuration that assumes white innocence is that it masks the dangerous ways seeing race is linked to knowing racialized interests where such knowledge may well be put to use to support systems of white privilege. This is evident in Bell’s (1992) work. Bell disputes the claim that knowledge, even a kind of ‘‘racial data storms,’’ produces antiracism. He states, ‘‘we fool ourselves when we argue that whites do not know what racial subordination does to its victims. Oh, they may not know the details of the harm, or its scope, but they know. Knowing is the key to racism’s greatest value to individual whites and to their interest in maintaining the racial status quo’’ (1992, 151). Bell’s approach is the antithesis of Mills’s. Instead of assuming whites innocently inhabit a consciousness of racial ignorance and misunderstanding, Bell reminds us that it is possible that whites know and that it is through knowing that whites maintain white privilege. Seeing and Surveilling The car carrying O.J. Simpson along the Los Angeles freeways was the most watched object in American history ... .The significance of his chase lies only partly in the man who was seen and more in the ability to see him ... .The development of surveillance technology is fueled of course by the social need to see and that, in turn is motivated by the social significance of that which must be seen. In a racially unstable society where whites are about to lose their dominance in numbers and fear losing it in politics and economics, the need to have the threatening other always in sight is paramount. In the contemporary USA the Black man is he who must be seen. (Fiske 1998, 67) Fiske offers an account of the real life ‘‘racialized data storms’’ that are a product of contemporary practices of state surveillance. He examines contemporary surveillance as a racialized set of technologies that materialize the white gaze, rendering especially African American men tracked, always watched: ‘‘In the contemporary USA the Black man is he who must be seen.’’ Surveillance of the kind Fiske describes is necessary to make society legible/visible, as, Scott argues, the modern state requires. But for Fiske, the emergence of widespread reliance upon surveillance in contemporary political societies is due in large part to the interests of whites in keeping racial superiority intact by ‘‘seeing’’ and ‘‘arranging’’ racial others: ‘‘ ... the surveillance that both Orwell and Foucault understood to be essential to the modern social order has been racialized in a manner they did not foresee: today’s seeing eye is white, and its object is colored’’ (1998, 69).13 While Hochschild and others might tend to offer explanations for seeing and blinding that seem to excuse ignorant whites, Fiske and Bell offer accounts of white envisionings that stabilize racist practices and institutions. Fiske writes, ‘‘The high visibility of the structures of democracy masks totalitarian undercurrents and offers those who prefer not to see an alibi for their blindness. In the real of race relations this motivated blindness has produced what we may call a ‘non-racist racism’’’ (1998, 70).14 The visibility of nonwhites, specifically their criminalized visibility, is necessary to constructions of superiority and inferiority. Alcoff has pointed out that race and gender are ‘‘our penultimate visible identities’’ (2006, 6). Visibility is linked to assumptions about what we can see is what is real (6). And, what distinguishes race and gender from identities such as political party or membership in the Sierra Club is the link between visibility, knowledge, and reality. Race and gender are forms of social identity that share at least two features: they are fundamental rather than peripheral to the self—unlike, for example, one’s identity as a Celtics fan or a Democrat—and they operate through visual markers on the body. In our excessively materialist society, only what is visible can generally achieve the status of accepted truth. What I can see for myself is what is real; all else that vies for the status of the real must be inferred from that which can be seen, whether it is love that must be made manifest in holiday presents or anger that demands an outlet of violent spectacle. (Alcoff 2006, 6) The attention to blindness may lead to the neglect of sight and seeing. Fiske continues, ‘‘Black behavior is seen, white behavior is not, and the difference is solely one of color: blackness is that which must be made visible, just as invisibility is necessary for whiteness to position itself as where we look from, not what we look at’’ (1998, 78). To see the other is to be able to make both discriminating choices and to see oneself as the norm, as the standard of what it means to be good Racism is the paradigmatic instance of abnormalization by visible and thus surveillable category. The abnormalization of the racial other that enables the DEA to identify drug runners by what they look like, the banks similarly to identify fraudulent credit card users, and the store to identify shoplifters by their appearance rather than their behavior, is a process without which surveillance cannot work, whiteness cannot work and totalitarianism cannot work. At the core of this process is, of course, the way that whiteness normalizes itself, and excludes itself both from categorizing and from being categorizable: it thus ensures its invisibility—an invisibility that extends into the widespread white ignorance of such incidents. Whiteness wants to see everything except its own operations. (Fiske 1998, 84) Vision then acts at least as a twopronged means of perpetuating white supremacy. First, the vision ignorance-intentionality configuration offers whites a cover for the overt and covert forms of racial dominance. Second, this very same vision-centered approach works in a different way to be the means through which contemporary racism is enforced, above, below, and many times beyond the law. A vision-orientation to understanding why whites seem to allow the perpetuation of racism ends up perpetuating racism: whites are color-blind, so ‘‘they don’t mean to be racist,’’ or they see race but through a lens that perpetuates threatening visions of racialized others and so justifies continuing the racialized surveillance practices that maintain the existing meaning of race. Surveillance as a practice recognizes that because we cannot see everything at once, because there are blind spots, we must focus our visual attention. Race, and particularly the anticipation of racialized violence, focuses our attention. But, many whites interpret surveillance as vision in the sense that vision is simply seeing what is already out there. Surveillance is then depoliticized, objectified, as vision in the unacknowledged service of maintaining white privilege. Taken together, both the practiced blindness and the call for white seeing seem to have limited transformative potential. Ultimately visual metaphors and surveilling practices may be poorly equipped to capture the politics of race. White vision is one-way, and the gaze is unreturned, incontestable, and therefore unaccountable. The Responsibility to Know The conventional framework for accountability begins with an assumption that moral reflection occurs after or in response to a vision of our social world that is taken as given. On this account, we perceive a social world of which there is, presumably because it is an objectively real world, an intersubjectively shared description. Contestation and ultimately moral judgments come into play in response to conflicts over which values take priority with respect to this given world. Vision metaphors are most often ways of capturing this givenness. But as Mills noted earlier, ‘‘objective cognition, factual and moral, in a racial polity are in some sense more demanding in that officially sanctioned reality is divergent from actual reality.’’ Mills then assumes (as Bell does not) that eliminating this divergence is the key to making a more racially just society. Given the ways practices of surveillance reaffirm racist visions or truths about the world, correcting for the white gaze will be an extremely challenging project. In what follows, we draw on insights from feminist epistemology and moral theory to develop a model of political and politicized accountability that we propose takes seriously but also moves us beyond the stalemate regarding white good will that is at the center of the Mills-Bell disagreement. The democratic renegotiation of this official reality requires a turn in the direction of what Scott (1998) describes as an alternative to the epistemological assumptions associated with high modernism and the seeing state. He suggests that in oral as opposed to legible cultures, the fixity of official envisioning can be resisted with ‘‘tales and traditions currently in circulation vary(ing) with the speaker, the audience and local needs’’ (332). Feminist ethicists, particularly work by Walker (2007), Calhoun (1995), and Blum (1991), call attention to the ways that the attribution of responsibility is a practice embedded in storytelling. Blum and Walker in particular suggest the importance of shifting to a model of moral judgment that emphasizes the place of our moral judgments in shaping our descriptions and our narrations, rather than merely responding to objective or officially sanctioned realities. We can be more or less attentive to the ‘‘weal and woe’’ of others.15 He illustrates this with an example of passengers on a bus. A passenger describing the scene may describe a bus in which all seats are occupied, and four riders stand. Alternatively, a passenger may describe a bus in which all seats are occupied, and one of the four riders standing is uncomfortably trying to manage groceries and a child. Both passengers have ‘‘seen’’ the world of the bus accurately, but the latter description attends to the ‘‘weal and woe’’ of other agents in a way that has implications for morally responsible action. Similarly, Walker rejects the possibility of formulating moral responsibility as an ‘‘impersonal code,’’ a ‘‘view from nowhere’’ that guides action in response to a prior and nonmoral description of the world. One way to understand Walker’s approach is as one that rejects the givenness and stability presumed with sight. She argues instead for an expressive collaborative model that creates the openings for a more responsible attentiveness to our social relationships and relevant identities. The narrative form, the idea that a story (rather than a vision) ‘‘is the basic form of representation for moral problems’’ (1998, 116), moves us decisively away from the visual metaphors that secured the epistemology of ignorance. ‘‘A narrative of relationship is a story of the relationship’s acquired content and developed expectations, its basis and type of trust, and its possibilities for continuation’’ (109–10). While both Blum and Walker broaden the scope of responsibility significantly, neither is naive about the roles that systematic, structural inequalities play in shaping the conditions of moral relationship. It is also sometimes said that ‘anyone,’ may make moral judgments, without special powers or office. But that’s not descriptively accurate, either. Making a moral judgment is assuming a kind of authority, at least the authority of grasping and speaking for a common standard (Smiley 1992, 239). Not just anyone has standing to enter any and all judgments, including moral ones, even if an ascendant modern political morality pictures moral equality or a ‘‘kingdom of ends’’ as an ideal. (Walker 1998, 96–97) Both Blum and Walker recognize the ways in which authority is racialized and gendered and that the narrative understandings we have for our relationships reflect this. Walker, in particular, attends to the problem of ‘‘subsumed identities’’ in which subjects ‘‘ ... are pressed toward selfdescriptions that serve plot functions in someone else’s tale within societies in which having one’s own story, quest, or career, is emblematic of full moral agency’’ (1998, 128). At the same time, she says, ‘‘There is no reason to think that many human beings under circumstances of subordination, oppression, or unfreedom of many types do not exhibit valor, perseverance, lucidity, and ingenuity in staying true to what they value within the confines of their situations’’ (123). Walker insists on the moral authority of subordinated people as narrators of the social and political.16 While she acknowledges the ways in which our narrative frames reflect dominant stories and many will reflect white privilege, Walker argues for the moral worthiness of accounts from the perspectives of the marginalized and assumes the plurality of stories. As Scott notes, ‘‘the clarity of the high-modernist optic is due to its resolute singularity. Its simplifying fiction is that for any activity or process that comes under scrutiny [surveillance] there is only one thing going on’’ (1998, 346).17 Vision itself is a narration, but it is one committed to singularity and thus incontestability. Moving beyond ignorance and innocence to a racially responsible politics requires the move to plurality, but this must be seen as a necessary but insufficient condition for democratic renegotiation of racial orderings. With Walker’s commitment to plurality and from the critical perspective of Mill’s epistemology of ignorance, the critical question is how to avoid the narratives we are ‘‘pressed toward’’— narratives which reinforce ignorance, exploitation, and racism, and which are both morally and politically irresponsible. Given the equality commitment that is explicit to our democratic commitments, responsibility requires citizens to create the space for alternative narratives that illuminate and ultimately challenge racism. This project requires both an understanding of where, why, and for whom existing narrative forms fail and a tentative but hopeful reconstruction of political practices of accountability for and dismantling of white privilege . An explicit commitment to narrative or storytelling approaches to framing responsibility has three significant consequences. First, ‘‘ignorance’’ may be no excuse—for we may be held accountable for our attention or inattention to the weal and woe of others for the stories we generate as well as the stories we ‘‘hear.’’ Put another way, there may be more and less racially responsible descriptions of the world. Second, blindness and vision become species of narrative— they are just two among many possible stories to be told, and we should not expect that we all share the same blind spots. A world in which we accept the vision of race constructed by and through white privilege and through racialized practices of surveillance as simply ‘‘true’’ is a world we participate in creating and re-creating through our acceptance, and it is a world which we can deconstruct through our resistance. Finally, because we can and should talk about both our blindnesses and our visions as ‘‘motivated,’’ they are appropriate objects of moral and political reflection. We can be held accountable for both our blind spots and our visions. But the practice of such accountability requires a move away from the visual metaphors to an explicitly recognized narrative framework for knowing and judging. The implications of this for an appropriate model of democratic accountability are critical. For there are official stories that narrate the vision of the surveilling state or that work to reinforce existing structures of privilege. The Political Economy of Our Attention to Suffering The explicit turn to recognize narratives of racism is not by itself a guarantee of a more racially responsible politics. The challenge to seeing like a state—hearing racism rather than merely seeing race through the white gaze—seems a necessary if not sufficient condition for recognizing and redressing racism. Stories too are motivated accounts. The work of Spelman (1997) suggests narratives of suffering and of the suffering experienced in racism in particular can work to reinforce rather than resist white privilege. Some narratives direct our attention to suffering in ways that are morally and politically problematic. To illustrate this, she outlines three common narrative forms through which attention is called to the suffering of racism. First, there is American slavery as ‘‘The American tragedy narrative,’’ which she argues centers our attention on the ways slavery constitutes white Americans as failing morally. In so doing, it turns our attention to issues of white conscience and ‘‘gives short shrift to the suffering of African American slaves’’ (Spelman 1997, 6). Alternatively, our attention can be directed to compassion as a way we are encouraged to respond to the sufferers to whom we are attending. Here Spelman draws on Harriet A. Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, written to appeal to those for whom compassion for the subjugated was seen as a virtue—white, Christian women of the northern United States. Jacobs was, Spelman argues, very much aware that this way of calling attention might reiterate rather than resist many of the patterns entrenched in white-black relations under slavery. Finally, she argues that attention to the suffering of others can narrratively position sufferers as ‘‘spiritual bellhops’’ for others. Here, the political concerns are particularly complicated. ... what if the borrowers are in fact more like scavengers, interested in the suffering of others not as a way of marking deep and pervasive similarities among suffering humanity, and making a case for mutual care, but mainly as a way of trying to garner concern simply for themselves. (Spelman 1997, 10) Spelman’s example here is the attempt by some white women in the mid-nineteenth century to call attention to their own economic, social, and political plight by referring to themselves as slaves. Spelman’s work identifies what Alcoff (1992) has called ‘‘the problem of speaking for others’’ even when that speaking attends to the racialized suffering of others.18 There are several related threads to this knotty problem: the first is the way in which speaking for others marks a failure to fully respect the autonomy that we attribute to members of a participatory democratic public. Paternalism is ultimately inconsistent with equal respect for participants as members of this community. Speaking for others is also consistent with manipulating public understandings of the interests of others to serve one’s own ends, and in this way, the problem of speaking for others is a problem of using others to advance one’s own interests. Stories, like blind spots and visions, can be motivated in ways that reflect privilege rather than resisting it. Finally, even where manipulation is not the goal, there is the epistemological problem of failing to ‘‘know,’’ to understand, the experiences or interests as well as one might think. Misunderstanding and misrepresenting in this way work to deny a democratic public access to information and understandings that may be a necessary if not sufficient condition for better decision making. But for our purposes here, the most damaging of consequences following from this misunderstanding is the way it both marks and perpetuates a denial of epistemological authority to those who are consistently spoken for. In the face of the ‘‘epistemology of ignorance’’ that produces race and racism, we have argued for a responsibility to know. Yet it is difficult to see how the narrative forms Spelman outlines facilitate or enact this responsibility as they largely amount to the appropriation of the experiences of suffering on the part of others to make gains for relatively more privileged groups. One way to address the problem of speaking for others is a more participatory and dialogical approach to the public and its moral and political problems—a more participatory democratic approach to recognition and remedy of racial suffering. But what Mills (1997), Fiske (1998), and Spelman (1997) suggest when taken together is that, even with a more inclusive voice, we have reason to expect collective attention to be directed away from redressing racism.19 And when our attention is called to see race, it can be called to it in a way that does little to challenge the epistemology of ignorance. Just as envisioning race through Fiske’s surveilling practices reinforces racism, the narration of racism when it takes the forms Spelman outlines may well reinforce rather than resist white privilege. Democracy, Accountability, and Antiracism To recognize and address racism, our attention then must shift not only to recognizing historically invisible sufferers—not merely making them ‘‘visible’’— but to hearing their own stories of suffering. One defense of this shift could clearly be located in a standpoint approach that draws from the work of thinkers such as Harding (1986), Hartsock (1983), or Collins (1990). The language of Mills’ epistemology of ignorance seems drawn from Marxist notions of ideology, and the idea that white supremacy reflects an inverted epistemology has its kindred spirits in later Marxism. Hartsock writes: ... the vision available to the oppressed group must be struggled for and represents an achievement that requires both science to see beneath the surface of the social relations in which all are forced to participate and the education that can only grow from struggle to change those relations. As an engaged vision, the understanding of the oppressed, the adoption of a standpoint exposes the real relations among human beings as inhuman, points beyond the present, and carries a historically liberatory role. (1993, 232) Mills seems at times to be implying the same kind of epistemologically privileged position for non-whites. Yet, he concludes not with a call to struggle for a collective recognition and respect for a voice that makes visible and accountable white privilege, but with a call for a more ideal social contract. Moreover, it is not clear how this more ideal social contract would be accomplished within the existing structures of white privilege. What does responsible white action look like in a context where the hypothetical conditions of contract typically ask for the erasure/ invisibility of whiteness altogether? This seems to evade white responsibility and a collective practice of accountability for white privilege. Alternatively, Collins (2000) has argued for the importance of challenging ignorance with an ‘‘outsider-within’’ standpoint which ‘‘by learning about lives on the margins, members of dominant groups come to discover the nature of oppression, the extent of their privileges, and the relations between them. Making visible the nature of privilege enables members of dominant groups to generate liberatory knowledge. Being white, male, wealthy, or heterosexual presents a challenge in generating this knowledge, but it is not an insurmountable obstacle’’ (Bailey 1998, 30). Collins sees outsider-within knowledge as both calling attention to the previously overlooked experience of marginalized groups and providing an opportunity for those in the center to learn to use knowledge generated by ‘‘outsiders within’’ to understand their relationships with marginalized persons from the standpoint of those persons’ lives. But this model ends up at least implying that ignorance and not motivation is the problem and so neglects the possibility, historically well-grounded, that understanding the marginalized may facilitate more effective and efficient means of exploiting the marginalized. Again, moving to the recognition of storytelling as the framework for thinking about moral responsibility, recognizing multiple stories, even privileging the stories of those historically excluded does some but not most of the work of democratic accountability. A model of democratic accountability must address privilege as producing both ignorance and interest. As such, it must encourage not only the voice of the marginal but also practices of engagement that disrupt privileged interest. Bailey contrasts three ‘‘archetypes of knowers: the disembodied spectator, the outsider within, and the traitor’’ (1998, 28). She describes ‘‘Traitorous Identities’’ in terms of privilege-cognizant white character. Traitors, as Bailey understands them, do not so much ‘‘become marginal’’ as they destabilize the center: ... traitors destabilize their insider status by challenging and resisting the usual assumptions held by most white people (such as the belief that white privilege is earned, inevitable, or natural). Descriptions of traitors as decentering, subverting, or destabilizing the center arguably work better than ‘becoming marginal’ because they do not encourage this conflation of the outsider within and the traitor. De-centering the center makes it clear that traitors and outsiders within have a common political interest in challenging white privilege, but that they do so from different social locations. (1998, 32–33) The essence of the challenge is to shift ‘‘scripts’’: ‘‘Privilege cognizant whites actively examine their ‘seats in front’ and find ways to be disloyal to systems that assign these seats’’ (1998, 37). Overcoming ignorance and acting with antiracist responsibility and democratic accountability will require whites to act ‘‘traitorously.’’ Ultimately, the traitor is made through traitorous acts, and it is in the nature of the traitor that she trades across politically contradictory locations and so cannot be sited (or sighted) or placed. Being disloyal is not in the end an alternative ‘‘identity’’ but a series of practices. An important aspect of this traitorous shift is the shift from a script centered on visions of race to one centered on stories of racism and from seeing to receptive listening as the orientation of the racially privileged toward racial ‘‘others.’’ One way to situate these narratives in relation to contemporary political projects is to think of this as a move to Walker’s ‘‘expressive-collaborative’’ approaches to moral relationship and to encourage the expression and reception of formerly excluded voices. It has its political manifestation in the call for voice in a participatory public. This collaborative, participatory project, if it is to remedy the ignorance and irresponsibility of white privilege, must foster two critical and traitorous companion practices. Testimonial Monologue as Counterstorytelling Speech needs to be authorized only where silence is the rule. It need not be obeyed and the justification of disobedience in this case is not a special kind of expertise guaranteed by epistemic privilege but rather by the demands of justice. (Bat-Ami Bar On 1993, 97) In moving to a narrative approach, it is natural to think first about locating narratives within a dialogical process. In part to resist the ways in which dialogue itself, as a form and not just the substance it produces, can reiterate systems of privilege, centering the monologue of racialized others is traitorous. Storytelling approaches moral inquiry, and the attention to a more inclusive voice in the context of democratic theory center the subject not as seeing subject, but as experiencing subjectgiving voice.20 Sanders (1997) and Young (2000) have both persuasively suggested that, in our political culture, those who are already underrepresented in formal political institutions and who are systematically materially disadvantaged, namely women, racial minorities, especially black and poorer people, will not be recognized (and, therefore, not heard) as characteristically deliberative. Democratic theorists concerned with elitism, participation, and informed discussion, as well as mutual respect for fellow citizens, ‘‘need to take one problem as primary. This problem is how more of the people who routinely speak less—who, through various mechanisms or accidents of birth or fortune, are least expressive in and most alienated from conventional American politics—might take part and be heard and how those who typically dominate might be made to attend to the view of others’’ (Sanders 1997, 352). Attending to the views of others is not automatically fostered even with the priority on deliberation as the practice that defines participation: ‘‘Prejudice and privilege do not emerge in deliberative settings as bad reasons and they are not countered by good argument. They are too sneaky, invisible, and pernicious for that reasonable process’’ (Sanders 1997, 353). This seems to be a truth about the workings of deliberation in practice that is rarely acknowledged. There is a good deal of faith in good reason. There is also the assumption that good reason allows us to prioritize the common over an explicit articulation of differences. This priority shapes not only what interests and arguments are given voice but also shapes our practices of listening. As Sanders notes, citing Benjamin Barber, ‘‘what is acknowledged by the listener is only what can be incorporated as identifiably similar’’ (1997, 361). Because theorists of deliberative democracy assume the requirement of mutual respect—a requirement Sanders sees us as having little good reason to assume will be met in actual practice—Sanders suggests the need to amend deliberative democratic practices with testimonial practices.21 ‘‘Instead of focusing so exclusively on deliberation, American democrats could cull an alternative model from their political history. The idea of giving testimony, of telling one’s particular story to a broader group, has important precedents in American politics, particularly in African-American politics and churches’’ (1997, 370). Drawing on Sanders’ critique, we want to shift to a practice that confronts inequality rather than assuming mutual respect. Such a confrontation begins with a commitment to monologue in the testimonial form. But it acknowledges that any adequate communicative infrastructure must not only be about including marginalized voices but also about receptivity to those voices. We outline what those practices of testimony and receptivity might look like. Sanders is persuasive in arguing that deliberative commitments alone are simply not enough to encourage the inclusion of the critical and transformative narratives of racism. She even frames the problem as an epistemological one at one point: ‘‘But their epistemological problem is perhaps more daunting: whites and Blacks see different worlds....’’ (1997, 370; emphasis ours). Testimonials are a way of describing ‘‘voice’’ that articulates the different worlds blacks see, and in so doing, at least puts open to contestation the objective and official visions produced by the white gaze. Sanders implies that it might be a remedy for the historical exclusions that mar deliberative achievement of equality. Race and racial identity are never stabilized but always understood as accomplished through a set of systematically enforced racialized practices in which whites participate, knowingly or not, and should therefore be understood as accountable. Racism as a practice cannot have meaning without whites; narrating racism is about both whites and nonwhites, and its content speaks, though in ‘‘disquieting ways,’’ very explicitly to all members of a racialized polity. In this sense, Balkanized storytelling both can and must be resisted. For these narratives, the narratives of racism narrated by racial others are not ‘‘their’’ stories rather than ‘‘mine,’’ but ‘‘ours,’’ and in this sense there is a collective responsibility to attend to, to listen, to hear, to respond, and to remedy racism. While the testimonial form is monological, its content looks much like what Nelson calls ‘‘counterstories.’’ Counterstories as Nelson understands them undermine a dominant story, undoing it and retelling it in such a way as to invite new interpretations and conclusions (1995, 23). Counterstories resist and undermine a story of domination. The author of a counterstory redescribes a dominant story, repudiates it for her or himself, and sets a new course that commits her or him to certain values for the future. When counterstories are told within a community, they can become ‘‘avenues of access.’’ They are always ‘‘stories of self-expression and self-definition, but they may also be stories of repair and resolution. The teller of a counter-story uses the story to elicit recognition from the community that has oppressed her. To do this, her story becomes, as it were, a pair of spectacles that she extends to the inhabitants of the normal moral context who can’t see her without them’’ (Walker 1998, 128; emphasis ours). Counterstories quite literally use testimonial narrative practices to enable a collective re-visioning through the practice of holding whites accountable. Testimonial practices have a more recent and global context as well. Truth and reconciliation efforts are often similarly defended as potential avenues for repair and resolution. Here expectations of testimony are in marked contrast to deliberative practice. Testimony is not a form of ‘‘reason giving;’’ there is not counter-reason-giving nor is there cross-examination. Storytelling is the expected form, and the veracity of particular details in the accounts is often viewed as less significant than the role the story plays in narrating the experience of mass violence and shaping a transformative process of collective meaning making. For many reasons, this seems an appropriate model for the narration of the experience of American racism, which is also an experience of pervasive violence on a wide scale. Testimonial offered by victims of mass violence is a way of acknowledging the importance of their epistemological, moral, and political authority with respect to historical experiences. Often testimonial practices challenge very explicitly ‘‘official histories.’’ Similarly, Nelson argues that the community that is the moral space for counterstories reauthorizes its members to take their judgments—judgments that challenge dominant or official accounts—seriously. Testimonial practices are themselves a recognition of the moral and political authority and not only the epistemological authority of racialized others. Not all members of a polity will concede to this reauthorization, and this is what makes narrating racism risky. Sanders’s hesitation about deliberation is that expecting this resistance, the historically marginalized will remain so even in a formally participatory setting committed to inclusive voice. While testimonial practices with their monological form are an important revision of a too simple commitment to voice as a remedy, the communicative infrastructure necessary to a deliberative politics that can take a transformative, antiracism seriously requires an elaborated conception of receptivity. The practice of ‘‘silent yielding’’ and attentive listening on the part of whites is necessary to fill out communicative practices central to a more hopeful racial politics and the accountability this requires. For the political economy of our attention to racism to shift, such receptivity must be developed. The responsibility to know racism cannot depend exclusively on an alternative account of voice; it requires too an alternative practice of listening. Silent Yielding The liberal reduction of talk to speech has unfortunately inspired political institutions that foster the articulation of interests but that slight the difficult art of listening ... silence is the precious medium in which reflection is nurtured and empathy can grow. (Barber 2003,174–75) It may seem ironic, but monologic practices accompanied by attentive silences may hold the key to establishing more robust democracies. Silent yielding, and the monologic testimonials and stories that accompany such yielding, are, taken together, practices that adhere to some of the most important facets of deliberative democracy. Ideally, deliberative democracy entails inclusive, dialogic, and transformative conversations. However, as theorists such as Young (1998, 2) and Sanders (1997) suggest, in racialized polities, the meaningful inclusiveness that is both the foundation and the anticipated outcome of democratic legitimacy has not been achieved. As a result of the historical dominance of white voices via enforced and hegemonic monologues of white interest and desire, a corrective series of monologues must be engaged. In this context the correctives of nonwhite testimonial and white silent yielding constitute democratically responsible action. Taken together, testimony and silent yielding disrupt white privilege and its organization of vision and voice in fundamental ways and move us closer to the conditions of equality that are requirements of democratic legitimacy. In the first instance, silence can be a moment of ‘‘awe,’’ as Dauenhauer (1980) describes it— a moral and political recognition of the ‘‘other’s’’ legitimacy and value reflected in the practice of receptivity to the voices of racialized others. Furthermore, as whites take on this role in deliberation, they also embody the practice of deliberation itself more honestly; in this sense, they may become more legitimate codeliberators in the eyes of nonwhite citizen subjects. It is in this moment of yielding and awe that hearing racism opens the way to re-visionings. Ellison’s Invisible Man states, ‘‘That invisibility to which I refer occurs because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact. A matter of the construction of their inner eyes, those eyes with which they look through their physical eyes upon reality’’ (1980, 3). And 50 years later, Frank Wu, author of Yellow, writes, ‘‘I alternate between being conspicuous and vanishing, being stared at and looked through. Although these conditions may seem contradictory, they have in common the loss of control’’ (2002, 8). Whites have simultaneously surveilled and made invisible nonwhites because they have controlled the terms and mechanisms of making visible and so their visions have dominated the discursive terrain. Resisting the white gaze, a re-vision, is accomplished through the narrations of black envisionings and the counterstories these generate. The transformative potential of these counterstories lies both in their telling as an act of collective struggle and in the moment that anticipates white receptivity even to the most unflattering of narrations of whiteness. Such counterstories may call for white subjects to be held to account for their blindness and their (en)vision(ing) as they recognize and reckon with alternative and collectively produced re-visionings. The often violently enforced norm that black Americans should not look whites directly in the eye is just one of the practices reinforcing the position of white privilege as unaccountable. To legitimate through the practice of silent yielding the testimony of nonwhite envisionings might also mean to confront, morally and politically, an accusing eye. In The Devil Finds Work, James Baldwin says, ‘‘The blacks have a song which says, ‘I can’t believe what you say, because I see what you do’’’ (1998, 522). The gaps between the things whites profess as democratic leaders and citizens and what they actually do is a gap that depends for its maintenance on avoiding or denying the accusing eye. Silent yielding, which paves the way for effective testimonials and stories, creates the discursive pause necessary to redirect attention to these gaps. A whiteness that cannot be looked directly in the eye, one whose gaze is fixed by narratives of white supremacy, and one whose ‘‘inner eyes’’ renders racialized others invisible, needs to start by hearing. There are two major points to be made about silent yielding, storytelling, and time. First, it is important to note the democratic temporality of silences that yield. These are moments in democratic dialogue, not permanent yielding postures; those who yield in silence are not forever silent, even on issues of race and racism. White subjects, as democratic participants, are expected to emerge from such silences better equipped to engage critically about issues of race and privilege. Being ‘‘better-equipped’’ does not mean that they remain silent when they engage nonwhite citizens. Instead, it means that silence as receptivity is a recognition of the inherent value of others as democratic participants. Even though silent yielding includes recognition of the other’s valuable epistemic authority, as a democratic practice it eventually is meant to lead to an open discussion and contestation in which privilege is shunned in favor of inclusive democratic dialogue. The second important point to be made about silence and time involves this less temporary goal of yielding and testimonial; silent yielding is meant to have a longlasting impact on democratic contexts in that it aims to dismantle privilege. On the one hand, silent yielding is a temporary transition point in which a historically privileged speaker yields the floor in order to better understand fellow citizens and allow for the inclusion of previously excluded voices. On the other hand, silent yielding is a more lasting attempt to undermine the very existence of privileged speakers who perpetuate white supremacy. Silence is most often situated as nonaction, as passivity, but silence might be the only viable communicative vehicle for an authentic antiracist politics among whites. Silent yielding as configured here is active and resistant, a ‘‘traitorous,’’ silence, a silence that participates in the transformative project to which contemporary deliberative democracy is committed. White silence as a complement to the testimonial practice of racial ‘‘others’’ forgoes the entrenched position of privileged democratic speaker. In other words, the combination of these practices aims to dismantle privileged speakership in favor of more thorough democratic dialogue. In creating the space for historically marginalized stories, it also creates the space for black envisionings and opens up possibilities for meaningful democratic accountability. Conclusion: Seeing Race, Hearing Racism An antiracist politics is better served by reconfiguring a responsibility to know. This requires a shift from discursive practices that position race as seen to practices that encourage attentive listening to the experiences of racism and a commitment to standing traitorously for antiracism before one’s fellow deliberators. The practices that move us in that direction include testimonial and silent yielding—practices that simultaneously enact and nurture a shift in authority over the meaning of race from the standpoint of those historically dominant toward those who have been racially subordinated. Seeing, gazing, and visibility undermine a thicker and politically necessary conception of responsibility by treating race relations as a product of visible and fixed racial identities, without attending to the ways these identities are produced and reproduced through practices of white privilege. To attend to practices and their meanings, and to confront the range of meanings any practice produces, means to take all democratic subjects as legitimate participants in the collective process of meaning making. Imagine a return to the scene and the seeing of the crime, a return to Henry Louis Gates, the arresting officer, and the neighbor who called the police to report that Professor Gates was breaking into his own home. The neighbor clearly saw two black men trying to enter a house, and that was all she needed to know. The arresting officer also saw a black man in his own home, yet would not listen to or empathize with Professor Gates’ frustration at being harassed and ultimately arrested in his own home. The arresting officer held a press conference, surrounded by a supporting cast, to speak out against Gates’ charges of racial profiling. The neighbor, the caller, spoke to media outlets about how the 911 tapes prove she is not a racist. And yet, it is still the surveilling white gaze that sites Gates out of place. And it is the officialdom of white privilege that focuses on a too empathetic black President and a heroic (trespassing) white cop. Imagine a different scenario. Imagine that the neighbor acted neighborly to Professor Gates. Imagine the officer on the scene practiced a silent yielding as a way to listen and construct an alternative reality in the doorway of Professor Gates’ home. Imagine a citizenry, a white citizenry, intent on deprivileging and dismantling their whiteness. This might begin by disputing, perhaps even dismissing, the authority of the arresting officer as the relevant ‘‘expert’’ on racial profiling, instead yielding in silence to the authority of a black President and a black Professor Gates to offer testimony to the pain and the degradation of racial profiling. It is only a system of pervasive white privilege that would resist their authority to be heard. Not talking about racism is complicity with racial violence. Denial of action is a priori unethical and perpetuates oppression. SUE 13 (Derald Wing Sue is a contributor to the teachers college at Columbia University, “Race Talk: The Psychology of Racial Dialogues,” American Psychologist, November 2013, https://www.rochester.edu/diversity/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Sue_RaceTalkArticle.pdf) In general, studies indicate that factors working against race talk are significantly different for people of color and for their White counterparts. Although White participants are disinclined to engage in race talk and/or address race issues superficially, people of color appear more willing to bear witness to their racial thoughts and experiences because it is such an intimate part of their identities. They feel shut off from discussing how race impacts their daily lives in society by the reactions to and perceived consequences of doing so. Furthermore, the contextual norms of our society can hinder race talk by setting the parameters for how it is discussed and interpreted, thereby placing people of color at risk for negative outcomes. For people of color, race talk is difficult because they are placed in the unenviable position of (a) determining how to talk about the “elephant in the room” when Whites avoid acknowledging it; (b) dealing with the denial, defensiveness, and anxiety emanating from their White counterparts; (c) managing their intense anger at the continual denial; and (d) needing to constantly ascertain how much to open up, given the differential power dynamics that often exist between the majority group and the minority group. For White Americans, the greatest challenge in achieving honest racial discourse is making the “invisible” visible. The conspiracy of silence allows them to maintain a false belief in their own racial innocence, lets them avoid personal blame for the oppression of others, and prevents them from taking responsibility to combat racism and oppression. Race talk threatens to unmask unpleasant and unflattering secrets about their roles in the perpetuation of oppression. Avoiding racial dialogues seems to have basic functions related to denial. The denial of color is really a denial of differences. The denial of differences is really a denial of power and privilege. The denial of power and privilege is really a denial of personal benefits that accrue to Whites by virtue of racial inequities. The denial that they profit from racism is really a denial of responsibility for their racism. Lastly, the denial of racism is really a denial of the necessity to take action against racism. Understanding the psychology of race talk from the perspective of White Americans and people of color has major implications for how educators can use this knowledge to facilitate difficult dialogues on race.