EarlyChildhoodCareandEducationinEthiopia-AQuestforQualityEducation

advertisement

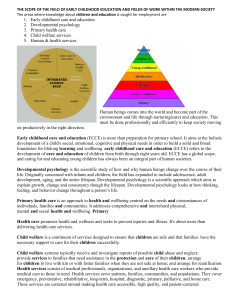

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351974585 Early childhood care and education in Ethiopia: A quest for quality Article in Journal of Early Childhood Research · May 2021 DOI: 10.1177/1476718X211002559 CITATION READS 1 2,562 2 authors: Boitumelo Molebogeng Diale Abatihun Sewagegn University of Johannesburg University of Johannesburg 24 PUBLICATIONS 65 CITATIONS 13 PUBLICATIONS 30 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Understanding Educational Psychology View project Cyberbullying View project All content following this page was uploaded by Abatihun Sewagegn on 29 August 2021. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE 1002559 research-article2021 ECR0010.1177/1476718X211002559Journal of Early Childhood ResearchDiale and Sewagegn Article Early childhood care and education in Ethiopia: A quest for quality Journal of Early Childhood Research 1­–14 © The Author(s) 2021 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X211002559 DOI: 10.1177/1476718X211002559 journals.sagepub.com/home/ecr Boitumelo M Diale and Abatihun A Sewagegn University of Johannesburg, South Africa Abstract Early childhood care and education (ECCE) has a crucial contribution to the future life of children, and overall quality of learning and development of a country. Even though there are no well-established international criteria to evaluate the quality of ECCE programmes because of the variability in nations’ economies, workforces, political regimes and cultures, there are some common standards. Therefore, the purpose of this review article is to assess the status of ECCE in Ethiopia and its contribution to quality education. This review is based on a document analysis from different sources (i.e. policy documents, books, journals, theses and dissertations). The study focuses on identifying common quality indicators/dimensions for ECCE and the challenges that Ethiopian ECCE faces in terms of these dimensions. Indicating that the practice of ECCE in Ethiopia is faced with diverse challenges. Some of the challenges are lack of proper training for teachers and caregivers; use of developmentally inappropriate curriculum; lack of pedagogical skill; unfavourable working conditions; inadequate resources; lack of continuous supervision and programme evaluation; inactive parental and community participation; ineffective school organisation and leadership; imbalanced staff-child ratios; and improper healthcare and hygiene. Therefore, the Ministry of Education (MoE) in partnership with the Ministry of Health (MoH), the Ministry of Women’s Affairs (MoWA), the community and other concerned bodies should work together to improve the practice of ECCE. Keywords Ethiopia, policy, early childhood, education, quality Introduction Education is the key to a better life for every child and the foundation of a stable society. If this is so, training, caring for and moulding children in the early years is essential and lays a foundation for a better country for the children are responsible for leading the country in the future. Early childhood refers to the period between 3 and 6 years of age (Plotnik and Kouyoumdjian, 2011) and it is a critical time in life when young children learn skills and develop abilities that set the foundation for Corresponding author: Abatihun A Sewagegn, Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, P.O. Box 524, APK campus, Auckland-park, Johannesburg 2006, South Africa. Email: abatihunalehegn@gmail.com 2 Journal of Early Childhood Research 00(0) future development. The term ‘early childhood care and education’ (ECCE) refers to a range of processes and mechanisms that sustain and support development during the early years of life: it encompasses education, physical, social and emotional care, intellectual stimulation, health care and nutrition. It includes the support a family and community need to promote children’s healthy development (UNESCO and UNICEF, 2012). Obiweluozor (2015) indicated that ECCE makes a positive contribution to children’s affective, conceptual and social development in later schooling years. Furthermore, ECCE plays a crucial role in improving the quality of education by reducing dropout rates in the later stages of learning (Ministry of Education [MoE], 2010). ECCE is becoming a growing priority as a base for a country’s development, and is recognised as a fundamental strategy in poverty reduction (Young Lives, 2010). Therefore, investing in ECCE is vital to achieving a country’s development goals. The Government of Ethiopia has shown a growing interest in improving the quality of ECCE programmes offered in early childhood education centres. This is reflected in the government’s Education Sector Development Programme V (ESDP-V) (MoE, 2015) and ECCE National Policy Framework, a strategic, operational plan and guideline for ECCE which the Ethiopian Ministry of Education (MoE) developed in collaboration with the MoH and the MoWA. The vision is to ensure that all children have a healthy start in life, are nurtured in a safe, caring and stimulating environment and develop to their fullest potential (MoE et al., 2010). In Ethiopia, the coverage and access to early childhood education is underdeveloped. It is limited mainly to cities and large towns and hardly exists in the rural areas (UNESCO-IICBA, 2010). Belay (2018) explained that, in urban areas, there are several non-governmental schools to which more affluent parents send their children while other more impoverished parents use the services of the limited number of faith-based preschools. To improve the availability and access to ECCE, the government in collaboration with private owners, non-government organisations, communities and religious organisations has implemented different types of ECCE programmes (MoE, 2016). These are O-class, child-to-child programmes and kindergarten. The O-class and child-to-child programmes were introduced to fill the access gaps in areas where kindergartens are not available, mainly in rural areas (Fantahun, 2016; Mulugeta, 2015). O-Class (is known as Zero Grade in Ethiopia) is a 1-year programme for children which is annexed to a primary school where children enrolled at age 6 stay for a year until they enter primary school (MoE, 2015; Rossiter, 2016). It serves as a reception year prior to Grade 1 (MoE, 2015). The rapid expansion of O-classes has raised concerns regarding the quality of childhood education provided (MoE, 2015). Child-to-child programmes are part of the early childhood education system in which older brothers or sisters (younger facilitators of Grade 5 or 6 students) play with their younger siblings and neighbourhood children (Fantahun, 2016; Mulugeta, 2015). This programme is not wellorganised but is designed to create access and opportunity for children to communicate with their older brothers and sisters and share their experience. Kindergarten is a programme for 4- to 6-year-old children. It is generally a 3-year programme at nursery, lower kindergarten and upper kindergarten. Kindergartens are primarily operated by private and faith-based institutions as opposed to the other two programmes, because of gaps, lack of staff and few schools in the public schooling system (Fantahun, 2016; Mulugeta, 2015). ECCE is considered an essential component of universal enrolment, retention and achievement in primary grades and later education (Reetu et al., 2017). However, there is lack of quality in such education in all three kinds of programmes in Ethiopia (Fantahun, 2016). The low quality of ECCE has an impact on children in later grades and even in higher institutions. Given that the quality dimensions/indicators for early childhood education are not adequately addressed in different studies which have been conducted locally and globally, the main purpose of Diale and Sewagegn 3 this review is to assess the status of ECCE from a quality perspective in Ethiopia. Hence, the following research questions are raised: 1. 2. What are the dimensions/indicators of quality ECCE? What are the challenges that hinder the provision of quality ECCE in Ethiopia? Concept of quality in early childhood care and education It is difficult to define quality because it is a broad concept concerning different variables and diverse contexts internationally. Fantahun (2016) noted that the quality of ECCE is a multifaceted issue which cannot easily be defined or measured. For our purposes, quality means meeting a predetermined set of standards or criteria. In this paper, quality ECCE is regarded as a system that is pedagogically and developmentally acceptable and lays the foundation for a child to become an active and productive member of society. From the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) formulated by the UN in 2015 to transform our world, provision of quality education (the 4th goal) is the focus of this research. The goal is stated as ‘ensuring inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning’. The Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development [ASCD] (s.a.: 2) defines quality education as follows, using the 2030 SDGs as a reference: quality education is one that focuses on the whole child - the social, emotional, mental, physical, and cognitive development of each student regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or geographic location and it prepares the child for life, not just for testing. Researchers and professionals agree that ECCE is the basis for quality education and country development. Heckman (2006) noted that access to quality ECCE could improve children’s future educational outcomes and set the foundation for later learning. In Rao’s (2010: 181) study, it was reported that ‘children in higher quality ECCE centres had better perceptual, memory, verbal and numerical skills than [those] with lower quality, indicating that quality is related to child outcome measures’. A quality ECCE system is characterised by the employment of qualified teachers, use of developmentally appropriate pedagogy, access to education facilities and healthy lifestyles including such things as a balanced diet and personal hygiene (Neuman et al., 2015). Whitebread et al. (2015) also noted that quality ECCE influences children’s academic development and their emotional and social well-being more powerfully than any other level of education. Researchers indicate the components of a quality early childhood education even if there is no clear-cut measure or standard. These are indoor and outdoor curriculum and activities, teacher and child relations, materials, nutrition and health factors, adequate experience and trained staff, knowledgeable and skilled staff (Fontaine et al., 2006). Some researchers use these as a standard or predetermined criterion for evaluation and accreditation of quality ECCE programmes. To some, coverage, efficiency, effectiveness and equity (Myers, 2006), teacher sensitivity, behaviour management, productivity and quality of the feedback (LoCasal-Crouch et al., 2007) are quality indicators in ECCE. Therefore, this review aims to identify the possible common standards/indicators of quality ECCE from a wide range of literature. Benefits of quality ECCE Teaching and caring children starting from their early years has major benefits for the children themselves and for the development of a country. ECCE plays a significant role in the introduction 4 Journal of Early Childhood Research 00(0) Quality ECCE at preschools Quality primary and secondary school education Quality learning in higher institution Competent and creative graduates/workforce to a country and the world at large will be produced. Figure 1. The quality chain at different education levels. of basic learning skills which are vital for their subsequent formal training at all levels of education (MoE, 2015). Investing in children in the early years improves their performance in later years of education. Children who have access to ECCE in their early years have a better background in the academic, social and behavioural dimensions of development. Investment in children at an early age makes a significant contribution to the quality of education in general and the future life of the child in particular. Whitebread et al. (2015) indicated that ECCE is critical for later academic achievement and overall well-being. According to Mwamwenda (2014: 1403), children who have had early childhood education have the following advantages as they are ‘less likely to repeat classes; less likely to drop out of school and are less likely to be assigned to special need classes’. He states that ‘ECE leads to higher achievement scores [and] higher completion rates in subsequent years of education’. There is also a ‘low correlation between such children and criminal activity’. Studies have recognised that ECCE provides several benefits, including social and economic benefits, better child well-being and learning outcomes as a foundation for lifelong learning. Quality ECCE is holistic in that it is not limited only to the provision of literacy and numeracy programmes to children (Fontaine et al., 2006). Instead, it integrates multiple services to improve the nutritional and health status of children, reduce the incidence of mortality, morbidity, malnutrition and school dropout and enhances the capability of mothers to care for and educate their children (Woodhead, 2014). Figure 1 shows the following figure shows the contribution of quality ECCE from preschool to higher learning institutions and its effect on the work environment. Research methods Data sources This section describes the approach and the data sources used to conduct the review study of the global literature that focuses on some quality ECCE issues and sources which focus on the current situation of early childhood care and education in Ethiopia in relation to quality. Government policy documents and reports, books, journal articles, conference/workshop papers, thesis and dissertations and educationrelated non-governmental associations’ research findings on ECCE-related issues were the sources used which are collected, identified and reviewed from scholarly and online databases (e.g. Google scholar, Diale and Sewagegn 5 Proquest, EBSCO, institution websites) and library catalogues from the University of Johannesburg (South Africa) and Debre Markos University (Ethiopia). The resources included in the review were identified by an online search. The search includes studies published between 2002 and 2019. Based on the research questions, 51 manuscripts were selected and reviewed. The types of the manuscripts were eight books, 21 journal articles, five theses and dissertations, 16 policy guidelines/papers/reports and proceedings of one conference. Eighteen of them were from Ethiopia and were peer-reviewed. Four were Ethiopian government publications. Studies and books which were related to ECCE and some formal education settings were considered in the review. Even though the focus of the review was the Ethiopia context, some international literature was included for a wider review. The following were search terms used to select manuscripts from scholarly and online databases. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Early childhood care and education Quality indicators for ECCE Dimensions of quality ECCE Challenges of quality ECCE Practice of ECCE Benefits of quality ECCE Developmentally appropriate curriculum Teacher and care giver training Pedagogical beliefs, skills and practices Working conditions in ECCE Parent and community involvement or participation Resources for ECCE Supervision, monitoring and evaluation School organisation Health care and hygiene Staff-child ratio Data analysis The data from the reviews were analysed and interpreted using descriptive-narrative analysis. Descriptive-narrative analysis involves the description of research findings and drawing conclusions from the literature (Cozby and Bates, 2012). The analysis and discussions of studies are presented based on the topics identified in the research questions, and finally, conclusions are given. Discussion Dimensions/Indicators of quality ECCE Researchers and professionals in ECCE set different standards or indicators to assess quality although they are not uniform because of the differences among nations in terms of their economies, political regimes, cultures, workforces and use of technology. In considering the differences in the definitions, components and elements of quality of ECCE, this paper highlights the common quality dimensions. The attributes of high-quality ECCE programme are the following. Appropriate training for teachers and caregivers. Well-trained, experienced and motivated teachers and caregivers are essential to the quality of ECCE and promote children’s development. Teacher 6 Journal of Early Childhood Research 00(0) education and training is the most important indicator of quality in ECCE (Whitebread et al., 2015) and an important policy issue (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2006). Without well-trained teachers, the ECCE goals cannot be achieved (UNESCO-IICBA, 2010). Neuman et al. (2015) also indicated that training could improve teacher performance and interactions, and that children do better with better-trained teachers in both formal and informal settings. Preschools children score better in tests when they learn with qualified teachers (Montie et al., 2006, cited in Neuman et al., 2015: 18). Whatever inputs in the educational system (management, facilities, resources or instructional materials) are available, they will be of little benefit if the teacher is untrained (Akinrotimi and Olowe, 2016). Neuman et al. (2015) stated that inexperienced teachers face challenges in using a playbased approach to teaching. Therefore, teacher training is critical in shaping pedagogical beliefs about how children learn best and high-quality ECCE. Use of developmentally appropriate curriculum. The curriculum is the vehicle through which any educational programme can be successfully implemented (Akinrotimi and Olowe, 2016) and a key determinant of quality ECE (Whitebread et al., 2015). According to Rossiter (2016), an effective ECCE curriculum will be play-based and will cover learners’ physical, cognitive, language, social, emotional, cultural, motivational and artistic needs. Developmental appropriateness is a widely used indicator of quality in education for young children (Fantahun, 2016) and is categorised as age-appropriate (i.e. it considers the age of children) and individualised (i.e. it is suited to the personality and learning style of the child). Developmentally appropriate curriculum materials are fundamental to the successful implementation of an ECCE programme and play a critical role in the quality of ECCE. A high-quality and well-implemented ECE curriculum provides developmentally appropriate support and cognitive challenges that can lead to positive child outcomes (Whitebread et al., 2015). An ECCE curriculum should incorporate a developmentally appropriate teaching approach for children’s age and experience. This means that what we teach and how we teach changes with age and knowledge (Belay, 2018). The medium of instruction is of major concern in ECCE, and it should be indicated in the curriculum. Literature recommends that use of mother tongue is appropriate in ECCE as the language of instruction and curriculum content should be culturally appropriate to the children’s environment (Singh, 2011). Content relevant curricula, textbooks, aids and materials are essential in ECCE. Story and picture books that reflect a country’s cultural values and moralities (Belay, 2018) should be included in the curriculum. Wood and Hedges (2016) also indicate that the curriculum should include all the activities and experiences in the setting, including the ethos, agreed rules and behaviours. They add that practitioners identify children’s interests and needs and plan the curriculum in emergent and responsive ways. In general, the ECCE curriculum should be developmentally appropriate considering the children’s ages, and personalities and learning styles. Favourable teacher beliefs and pedagogical practices. Favourable teacher beliefs and pedagogical practices are two critical indicators in ensuring quality childhood education. Neuman et al. (2015) add that teachers’ beliefs inform pedagogical practices and are key factors in ECCE programme quality. Use of developmentally appropriate teaching methods is one of the characteristics of pedagogically qualified teaching staff. High-quality pedagogy relates to how staff engages children, support their learning, and stimulate interactions with other children (Parker and Newharth-Pritchett, 2006). As mentioned above, training is vital and can help to shape teachers’ beliefs that affect pedagogical practices in the classroom and impact how they develop activities for the children (Neuman et al., 2015). Conducive working conditions. Conducive working conditions motivate staff members who have better qualifications to join the ECCE work environment. Excellent salaries, appropriate staff-child Diale and Sewagegn 7 ratios and working hours are structural quality indicators for conducive working conditions, influence the ability of staff to do their work well and impact their job satisfaction (OECD, s.a.). OECD (s.a.) also stated that non-financial benefit, workload, teamwork and managers’ leadership are other features of conducive working condition that influence the ability of professionals in ECCE. Neuman et al. (2015) indicated that low job satisfaction and high turnover are the results of inadequate salaries and other poor working conditions (such as limited resources, poor leadership, long working hours without additional incentives) and these create a challenge in attracting and retaining quality ECCE professionals in the work environment. Low salaries for ECCE staff may discourage trained and committed individuals from joining the profession (OECD, 2010). Therefore, conducive working conditions are an excellent indicator for quality ECCE. Adequate resource/facilities. Resources are essential for the successful implementation of an ECCE programme (Akinrotimi and Olowe, 2016) and should be accessible and appropriate for children (Whitebread et al., 2015). Specifically, indoor and outdoor facilities that encourage a play-based approach are essential in ECCE services. Making resources accessible at preschools helps the caregiver or the teacher to encourage and support children more appropriately and implement the curriculum effectively. The indoor and outdoor materials and equipment contribute significantly to attracting and maintaining the attention of children. It also makes the teaching-learning process more concrete, suitable and easily understandable (Astatke and Kassaw, 2017). More particularly, locally produced instructional materials are vital in creating different mental maps and conceptual understandings (Chowdhury and Choudhury, 2002). In addition to the indoor and outdoor materials, child-sized chairs, toilets and appropriate classroom space make a contribution to the quality of ECCE. Continuous supervision and programme evaluation. An effective ECCE system includes a monitoring and evaluation mechanism to strengthen quality (Rossiter, 2016) and continuously supervising and evaluating the ECCE programme is one of the essential elements of ensuring quality. The supervision and evaluation help to detect gaps in the implementation of the ECCE programme. In the supervision process, information can be gathered from children, parents, caregivers and communities, and can be used to correct errors and modify practices (Awino, 2014). Awino (2014) added that supervision in early childhood education leads to the holistic development of children, enables efficient implementation of curriculum and checks whether the objectives of the programmes have been achieved. Active parent and community participation. Active parent and community participation are vital for the quality of ECCE. Parents’ participation in education is a right and they have a duty to monitor their children’s education, growth and protection (OECD, 2010) as they have the first and continuing responsibility for teaching their children about life, behaviour and conduct (Andrea, 2016). Parental engagement in school contributes to the children’s later academic success, socio-emotional development and high school completion. In this regard, Neuman et al. (2015) indicated that close communication and interaction between children, parents and other professionals are crucial for the quality of ECCE. Whitebread et al. (2015) added that staff (teachers, caregivers and practitioners) and families must work together to ensure the best quality of ECCE. ECCE requires a strong partnership between the family, community, teachers, caregivers, practitioners and professionals. Fantahun (2016) stated that the ECCE partnership combines the knowledge and experiences of parents and ECE staff, both of which are important in the child’s life. Andrea (2016) also indicated that the partnership between families and ECCE professionals involves sharing information, ideas and questions about the child. Parents or other guardians 8 Journal of Early Childhood Research 00(0) should have the primary educational responsibility for their children. Parents better understand the childhood education programme offered by preschools if they are involved in children’s learning at home and school (Chan and Chan, 2003). Durisic and Bunijevac (2017) listed six factors or ways of effective parental involvement: parenting, learning at home, communication, volunteering, decision making and community collaboration. The involvement of the community in ECCE plays a central role in the development of children (OECD, 2010). If the relationship between schools and communities is active, it is easier for children to develop the skills needed to thrive physically and academically, socially and emotionally (OECD, 2006). Effective school organisation and leadership. Good school organisation and leadership significantly contribute to the active teaching-learning process, enhance teachers’ motivation and improve the quality of education. Research shows that effective school organisation and leadership are a valuable source of success in children’s learning (Abebe and Woldehanna, 2013). Therefore, school directors or head teachers should be properly trained on how to manage, monitor and supervise the activities of teachers in schools and classrooms. Neuman et al. (2015) noted that proper training and education equip ECCE personnel with the skills, knowledge and beliefs to create quality learning environments that ultimately improve child outcomes. Balanced/appropriate staff-child ratio. The balance between the staff (teacher/caregiver) and the child in the classroom contributes to the quality of childhood education. Reetu et al. (2017) noted that an appropriate teacher-children ratio is the significant aspect of quality ECCE. A low teacher/ child ratio enhances the quality of ECCE (Huntsman, 2008; OECD, s.a.) and improves the relationships between the teacher and the child. This plays a fundamental role in child development and academic achievement (Whitebread et al., 2015). When the number of children is smaller, caregivers can interact better with them and provide more support to children with special needs (OECD, s.a.). Whitebread et al. (2015) also explained that teachers’ interactions with children in smaller groups are more responsive, sincere and supportive. Huntsman (2008) added that a low teacher/ child ratio makes children more cooperative in activities, and children tend to perform better in different assessments. In contrast, a higher teacher/child ratio in early childhood education settings will not allow caregivers to give sufficient attention to children and the children may experience neglect (Akinrotimi and Olowe, 2016). This has a negative impact in the quality of ECCE. Proper healthcare and hygiene. Physical care is not the only responsibility of the caregiver. Family, teachers and other school members should also take care of the psychosocial well-being of the children. Teachers’ skill in treating children, knowing how to approach them, for example, smiling and greeting them when they come to the school, is essential elements in quality ECCE. Quality ECCE programmes encompass early learning as well as health, nutrition, hygiene, safe water, sanitation, affection, care and protection of children (UNESCO and UNICEF, 2012 as cited in Reetu et al., 2017). Sanitation/hygiene, safety, security and follow-up if there are problems of any kind are critical to the quality of ECCE. Figure 2 shows the possible dimensions /indicators of quality ECCE. Challenges that hinder the provision of quality ECCE in Ethiopia Studies conducted in Ethiopia have listed several problems in the practice of ECCE. In this review, the main challenges that hinder the provision of quality ECCE in Ethiopia are summarised and presented in different categories. Diale and Sewagegn 9 A. Appropriate teachers and caregivers’ training B. Use of developmentally appropriate curriculum C. Favourable teacher beliefs and pedagogical practices D. Conducive working conditions E. Adequate resource/facilities F. Continuous supervision and programme evaluation Quality ECCE G. Active parent and community participation H. Effective school organisation and leadership I. Balanced/appropriate staff-child ratio J. Proper healthcare and hygiene Figure 2. Dimension/indicators of quality ECCE. Lack of proper teacher and caregiver training Teachers’ training plays a significant role in education in updating and giving new information to the trainees and filling the gaps that the trainees have. However, studies conducted in Ethiopia indicate that most preschool teachers are untrained or have minimal training (Assefa, 2014; Mulugeta, 2015; Tirussew et al., 2009) and staff have irrelevant or only slightly relevant qualifications (Astatke and Kassaw, 2017; Fantahun, 2016; Haile and Mohammed, 2017; Rahel, 2014; Tigistu, 2013). Even the caregivers in private kindergarten schools in urban areas provide services without having pre-service or in-service training (Astatke and Kassaw, 2017). Haile and Mohammed (2017) found that there is a lack of accessible training institutions. Furthermore, the training given is too theoretical and insufficient to support practitioners to acquire the required professional skills for the real work setting. Tigistu (2013) adds that, in Ethiopia, trainees often enrol at preschool colleges when they do not have options or opportunities to pursue higher education studies in other professions or fields of study. Use of developmentally inappropriate curriculum Developmentally inappropriate curriculum means a curriculum that does not consider the children’s ages, children’s personalities or learning styles. Though developmentally appropriate curriculum and teaching strategy are determinant factors for a quality preschool programme, the curriculum that is being implemented and the teaching strategy practised in Ethiopia are far from satisfactory (Fantahun, 2016). Teka et al. (2016) found that lack of developmentally appropriate books and other relevant learning materials were the challenges observed in ECCE centres in Ethiopia. Lack of standard curriculum-based books and guidelines; lack of culturally relevant storybooks; the misconception that anybody can teach young children; and the use of a foreign language as the language of learning and teaching in private preschools (mainly English instead of the mother tongue) that makes the use of local stories challenging (Astatke and Kassaw, 2017; Haile and Mohammed, 2017; MoE, 2010). Belay and Belay (2016) added that no significant initiative was observed to incorporate locally produced resources for educational purposes. 10 Journal of Early Childhood Research 00(0) According to Fantahun (2016), another challenge for most preschools about the curriculum was parents’ unrealistic needs. Parents want their children to speak English, and preschool teachers and owners try to meet parents’ needs by teaching children English at the expense of other learning experiences. Parents compare one preschool with others in terms of the children’s ability to speak English, and this parental interest seems to influence the curriculum content of most preschools and the quality itself (Fantahun, 2016). Lack of pedagogical skill Teaching preschool children requires not only academic mastery but also pedagogical skills of managing and understanding their behaviours. However, the pedagogical skill that the current preschool teachers have in Ethiopia is inadequate because of a lack of institutions that provide such training as well as lack of professional teachers who have specialised in the area. As a result, there is improper management of children by non-professional preschool teachers, which may result in several adverse outcomes on children like school phobia, low academic achievement in later grades and a high dropout rate (Abebe and Woldehanna, 2013; MoE, 2015). Studies conducted in Ethiopia show that teachers possess little understanding of pedagogical principles about teaching very young children (Tirussew et al., 2009) and all preschools lack appropriate teaching methods to meet desired quality criteria in ECCE (Haile and Mohammed, 2017; Rahel, 2014). Assefa (2014) also found a similar result saying that using different teaching methods which are appropriate to children was one of the greatest challenges faced by the preschool teachers. Bruce (2011) about the preschool teaching method stated that children could not learn without real, direct and first-hand experiences. Unfavourable working conditions Conducive working conditions and job satisfaction make a crucial contribution to the quality of ECCE. However, studies conducted in Ethiopia showed that low salaries of teachers and high teacher turnover are challenges that affect practices and the quality of ECCE (Astatke and Kassaw, 2017). Inadequate resources/facilities Although resources or facilities are determinant factors for the quality preschool programme, what is observed in the Ethiopian preschools is inadequate as different research results have demonstrated. For example, Haile and Mohammed (2017) found that insufficient classroom space, ageinappropriate chairs and unavailability of outdoor playing materials are problems. Unavailability and lack of safe playgrounds and materials, child-sized tables, chairs and shelves, classroom space per child, separate restrooms for the children and child-sized toilets (Assefa, 2014; Astatke and Kassaw, 2017; Tirussew et al., 2009) are problematic. Also, the absence of clean, well-ventilated and well-lit classrooms (Astatke and Kassaw, 2017) was a challenge. An inaccessible physical learning environment, inaccessibility of indoor-outdoor materials (Astatke and Kassaw, 2017; Rahel, 2014) and lack of equipment for children with disabilities, unavailability and the high cost of educational materials, lack of standardised classroom space and absence of recreation areas (Astatke and Kassaw, 2017; Rahel, 2014) were observed as challenges. Lack of continuous supervision and programme evaluation Supervision and programme evaluation activities make a contribution to the quality of ECCE. However, different research reports have shown that there is lack of monitoring to maintain the Diale and Sewagegn 11 standard of the curriculum and other facilities in preschools and in the training of preschool teachers (MoE, 2010; UNESCO-IICBA, 2010). Effective supervision is a process that entails keeping check and monitoring to ensure curriculum implementation is done effectively and efficiently (Akinrotimi and Olowe, 2016). A robust monitoring and evaluation system will be able to assess whether a child is receiving all essential services, how services are delivered and how the system is functioning (Richter et al., 2014). Inactive parent and community participation Parental and community participation play a pivotal role in the quality of ECCE. However, in the Ethiopian context, parental and community participation is not clearly understood in preschools, most of them have no such practice of working with communities (Fantahun, 2016) and parental involvement is limited (Belay, 2018). Even programme policies do not specify what is expected of the families and communities in the education of preschool children. Fantahun (2016) added that guidelines are not established as to how parents could participate and could be involved in the preschool programme in most preschools. Tsegaye (2017) found that parents’ involvement in the education of their children was minimal and they did not regard preschools as a place for learning and fun, but were used for feeding their children and looking after them during workdays. Ineffective school organisation and leadership Effective leadership and school organisation make a positive contribution to the quality of ECCE. However, existing personnel working at the different levels of the education system related to ECCE have irrelevant or only slightly relevant qualifications (Tigistu, 2013) and ECE directors are not trained in ECE management (Tirussew et al., 2009). Studies have indicated that trained leaders are not assigned to lead and manage preschools. About this, Belay (2018) noted that untrained facilitators, administrators and supervisors are still commonly appointed to leadership positions. Imbalanced/inappropriate staff-child ratio There are is large number of children per staff member (teacher or caregiver) and this affects the quality of ECCE services. Studies have indicated that, in Ethiopia, preschool teacher-child ratio is high (Mulugeta, 2015; UNESCO-IICBA, 2010). The ratio significantly affects the child-adult interaction because the children cannot be given the individual attention they need (Essa, 2011). When an adult is in charge of too many children, both the children and adults are adversely affected. Low ratios facilitate interaction and allow for more individualised attention to each child. Improper healthcare and hygiene At preschools, healthcare and sanitation are the primary tasks of the school community (teachers, caregivers and other concerned bodies). However, most preschools in Ethiopia were not built for ECCE and did not consider the accessibility issue for preschool children in general and children with disability in particular (Astatke and Kassaw, 2017). Studies show that there is a lack of childsized toilets, the toilets were not kept clean and there were no portable water points (Astatke and Kassaw, 2017; Tirussew et al., 2009). 12 Journal of Early Childhood Research 00(0) Conclusion The review shows the possible dimensions/indicators against which to measure quality ECCE and the challenges that the Ethiopia ECCE programme faces in this regard. The identification of quality indicators helps to evaluate the practice of ECCE programmes and points out the gaps to be filled. From different studies, it has been found that ECCE can make a positive contribution to children’s wellbeing. The most important aspects of quality in ECCE are appropriate staff training (teachers, caregivers and practitioners); effective use of developmentally appropriate curriculum; favourable teachers’ beliefs and pedagogical practices; conducive working conditions; adequate resource/facilities; continuous supervision and programme evaluation; active parental and community participation; effective school organisation and leadership; a balanced/appropriate staff-child ratio, and proper care and hygiene. However, most of the ECCE centres in Ethiopia today are struggling to meet these standards, despite the efforts being made to improve the situation. Therefore, government, private, religious, non-government organisations and the community should work together to deliver quality childhood education and produce future citizens who will serve and bring change to the country. Further research The investigators addressed a range of research articles in the area of early childhood education. However, important papers may have been missed in the search. Therefore, further study or review using different search items and a broader time span is needed to address the issue more extensively. Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. ORCID iD Abatihun A Sewagegn https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0147-5190 References Abebe W and Woldehanna T (2013) Teacher Training and Development in Ethiopia: Improving Education Quality by Developing Teacher Skills, Attitudes and Work Conditions. Oxford: University of Oxford. Akinrotimi AA and Olowe PK (2016) Challenges in the implementation of early childhood education in Nigeria: The way forward. Journal of Education and Practice 7(7): 33–38. Andrea V (2016) Parents and educators: What are the components that govern a successful partnership in childcare settings? Master’s Thesis, Laurea University of Applied Sciences, Otaniemi, Finland. Assefa G (2014) Practices and challenges of early childhood care and education in Addis Ababa, Arada Sub-City government kindergartens. Master’s Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD) (s.a.) The 2030 sustainable development goals and the pursuit of quality education for all: A statement of support from Education International and ASCD. Available at: http://www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/siteASCD/policy/ASCD-EI-Quality-EducationStatement.pdf (accessed 23 September 2019). Astatke M and Kassaw K (2017) Early childhood care and education (ECCE): Practices and challenges, the case of Woldia Town, North East Ethiopia. Global Journal of Human-Social Science: Linguistics & Education 17(9): 1–11. Awino NL (2014) Impact of supervision on the implementation of early childhood education curriculum in selected public preschools in Lang’ata District, Nairobi County. Master’s Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya. Available at: http://cees.uonbi.ac.ke/sites/default/files/cees/fina%20final%20final%20 pdf_0.pdf (accessed 20 September 2019). Diale and Sewagegn 13 Belay T (2018) Early childhood care and education (ECCE) in Ethiopia: Developments, research, and implications. The Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review 34(1): 172–206. Belay T and Belay H (2016) Indigenization of early childhood education (ECCE) in Ethiopia: “A goiter on mumps” in ECCE provisions. The Ethiopian Journal of Education 36(2): 73–117. Bruce T (2011) Early Childhood Education, 4th edn. Oxon: Hodder Education. Chan LKS and Chan L (2003) Early childhood education in Hong Kong and its challenges. Early Child Development and Care 173(1): 7–17. Chowdhury A and Choudhury R (2002) Preschool Children: Development, Care and Education. New Delhi: New Age International Publishers. Cozby PC and Bates SC (2012). Methods in Behavioral Research, 12th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. Durisic M and Bunijevac M (2017) Parental involvement as an important factor for successful education. CEPS Journal 7(3): 137–152. Essa EL (2011) Introduction to Early Childhood Education, 6th edn. Ontario: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. Fantahun A (2016) Early childhood education in Ethiopia: Present practices and future directions. The Ethiopian Journal of Education 36(2): 41–72. Fontaine NS, Torre LD, Grafwallner R, et al. (2006) Increasing quality in early care and learning environments. Early Child Development and Care 176(2): 157–169. Haile Y and Mohammed A (2017) Practices and challenges of public and private preschools of Jig Jiga city administration. International Journal of Research: Granthaalayah 5(12): 17–32. Heckman JJ (2006) Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science 312(5782): 1900–1902. Huntsman L (2008) Determinants of quality in child care: A review of the research evidence. Available at: http://www.community.nsw.gov.au/_data/assets/pdf_file/ 0020/321617/research_qualitychildcare.pdf (accessed 12 October 2019). LoCasal-Crouch J, Konold T, Pianta R, et al. (2007) Observed classroom quality profiles in state-funded pre-kindergarten programs and associations with teacher, program, and classroom characteristics. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 22(1): 3–17. Ministry of Education (MoE) (2010) Early Childhood Care and Education Policy and Strategic Framework. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education (MoE) (2015) Ethiopia Education Sector Development Program V (ESDP-V): 2015/16–2019/20: Program Action Plan. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education (MoE) (2016) Educational Statistical Annual Abstract. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Ministry of Women’s Affairs (2010) Strategic Operational Plan and Guideline for Early Childhood Care and Education in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: MoE, MOH & MoWA. Mulugeta T (2015) Early childhood care and education attainment in Ethiopia: Current status and challenges. African Educational Research Journal 3(2): 136–142. Mwamwenda TS (2014) Early childhood education in Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5(20): 1403–1412. Myers RG (2006) Quality in program of early childhood care and education (ECCE): Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2007. Strong foundations: Early childhood care and education. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001474/147473e.%20 pdf (accessed 10 October 2019). Neuman MJ, Josephson K and Chua PG (2015) A Review of the Literature: Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) Personnel in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Results for Development Institute. Paris, France: UNESCO. Obiweluozor N (2015) Early childhood education in Nigeria, policy implementation: Critique and a way forward. Africa Journal of Teacher Education 4(4): 1–8. OECD (2006) Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. 14 Journal of Early Childhood Research 00(0) OECD (2010) Encouraging quality in early childhood education and care. Research Brief: Parental and Community Engagement Matters. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/education/school/49322478.pdf (accessed 17 May 2019) OECD (s.a.) Encouraging quality in early childhood education and care. Research Brief: Working Conditions Matter. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/edu/school/49322250.pdf (accessed 17 May 2019). Parker A and Newharth-Pritchett S (2006) Developmentally appropriate practice in kindergarten: Factors shaping teacher beliefs and practice. Journal of Research in Childhood Education 21(1): 63–76. Plotnik R and Kouyoumdjian H (2011) An Introduction to Psychology, 9th edn. New York: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. Rahel G (2014) Quality of early childhood care and education: The case of selected government ECCE centers in Bole and Kirkos Sub-cites in Addis Ababa. Master’s Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Rao N (2010) Preschool quality and the development of children from economically disadvantaged families in India. Early Education and Development 21(2): 167–185. Reetu C, Renu G and Adarsh S (2017) Quality early childhood care and education in India: Initiatives, practice, challenges and enablers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education 11(1): 41–67. Richter L, Berry L, Biersteker L, et al. (2014) Early Childhood Development: National ECD Program Short Report. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council. Rossiter J (2016) Scaling up access to quality early education in Ethiopia: Guidance from international experience. Young Lives policy paper. Oxford, England: Young Lives. Singh NK (2011) Culturally appropriate education: Theoretical and practical implications. In: Reyhner J, Gilbert WS and Lockard L (eds) Honoring Our Heritage: Culturally Appropriate Approaches to Indigenous Education. Flagstaff: Northern Arizona University, pp.11–42. Teka Z, Daniel D, Daniel T, et al. (2016) Quality of Early Childhood Care and Education in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Institute of Educational Research, Addis Ababa University. Tigistu K (2013) Professionalism in early childhood education and care in Ethiopia: What are we talking about? Childhood Education 89(3): 152–158. Tirussew T, Teka Z, Belay T, et al. (2009) Status of childhood care and education in Ethiopia. In: Tefera T, Dalelo A and Kassaye M (eds) First international conference on educational research for development, vol. I. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University Press, pp.188–223. Tsegaye TB (2017) The role of parents’ involvement in education of their preschool children and its relationship with academic performance and development of good manners of their children: The case of selected preschools of Kirkos Sub City of Addis Ababa. Master’s Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. UNESCO and UNICEF (2012) Early childhood care and education: Asia-Pacific End of decade notes on education for all. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/End_Decade_Note_-_Education_for_All_new. pdf (accessed 11 November 2020). UNESCO-IICBA (2010) Country-case studies on early childhood care and education (ECCE) in selected sub-Saharan African countries 2007/2008: Some key teacher issues and policy recommendations. A summary report: I-35. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: UNESCO. Whitebread D, Kuvalja M and O’Connor A (2015) Quality in early childhood education: An international review and guide for policy makers. World Innovation Submit for Education. Available at: https://www. wise-qatar.org/app/uploads/2019/04/wise-research-7-cambridge-11_17.pdf (accessed 16 September 2019). Wood E and Hedges H (2016) Curriculum in early childhood education: Critical questions about content, coherence, and control. The Curriculum Journal 27(3): 387–405. Woodhead M (2014) Early Childhood Development: Delivering Inter-Sectoral Policies, Programs and Services in Low-Resource Settings. Oxford: University of Oxford. Young Lives (2010) Policy brief: Early childhood care and education as a strategy for poverty reduction: Evidence from Young Lives. Available at: https://www.younglives.org.uk/content/early-childhoodcare-and-education-strategy-poverty-reduction-evidence-young-lives (accessed 15 September 2019). View publication stats