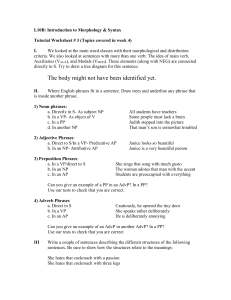

SYNTAX CONSTITUENCY, TREES, AND RULES Learning Objectives • 1. Be able to explain what a constituent is. • 2. Show whether a string of words is a constituent or not. • 3. Using phrase structure rules, draw the trees for English • sentences. • 4. Explain and apply the Principle of Modification. • 5. Produce paraphrases for ambiguous sentences and draw trees for each meaning. • 6. Define recursion and give an example. Introduction • What do we mean by structure? • Ex: The student loved his syntax assignments • The statement that this sentence consists of a linear string of words misses several important • • • • generalizations about the internal structure of sentences and how these structures are represented in our minds. In fact, the words in the sentence above are grouped into units (called constituents) and that these constituents are grouped into larger constituents, and so on until you get a sentence. Let’s agree upon the fact that certain words are closely related to one another. TWO notions are used to capture the intuition of close relationship: • A. Constituent: A group of words that function together as a unit. • B. Hierarchical structure: Constituents in a sentence are embedded inside of other constituents. • The idea that the and student are closely related to one another is captured by the fact that we treat them as part of a bigger unit that contains them, but not other words. There are 2 ways to represent this bigger unit (constituency) through either square brackets [the student] or a group of lines called ‘tree structure’ • Mind you! The “relatedness” is captured by membership in a constituent. Introduction • Constituents don’t float out in space. Instead, they are embedded one inside another to form larger and larger constituents. This is hierarchical structure. • This typical hierarchical treee structure can be read this way: • For example, the sentence constituent (represented by the symbol TP) consists of two constituents: a subject noun phrase (NP) [the student] and a predicate phrase or verb phrase (VP) [loved his syntax assignments], etc. • This tree has constituents (each represented by the point where lines come together) that are inside other constituents. This is hierarchical structure. Introduction • Hierarchical constituent structure can also be represented with brackets ([ ]): • Easy or difficult to read? • A BIT DIFFICULT Rules and Trees • Phrase Structure Rules (PSRs): • First, let’s introduce the terminology we need to use in order to describe sentences: • For example, the rule ‘NP → N’ says that an NP is composed of (written as →) an N. This rule would generate a tree like: Noun Phrases (NPs) • Optionality: • NPs can take the form of : • a noun only (John, water, cats), • a determiner and a noun (the box), • a determiner, an adjective and a noun (his yellow binder), • a determiner, more than one adjective, a noun and more than one prepositional phrase (the big yellow box of cookies with the pink lid) • The only obligatory categry in the above NPs is the noun; the rest are optional elements. Such optionality must be indicated in the rule via the use of parentheses ( ). Therefore, our NP rule should look like: • NP → (D) (AdjP+) N (PP+) (to be revised later) • The Kleene plus ‘+’ stands for the idea that the NP above must allow more than one adjective and more than one PP modifier. Adective Phrases (AdjPs) • Consider these two NPs: • 1. The big yellow book • 2. The very yellow book So, the rule for the AdjP looks like: AdjP → (AdvP) Adj • While in (1) the N is modified by two AdjPs, in (2) by only one. • Rrestriction on tree structures: • Principle of Modification : Modifiers are always attached within the phrase they modify (to be modified) Adverb Phrases (AdvPs) • Consider this AdvP: • 1. very quickly So, the rule for the AdvP looks like: AdvP → (AdvP) Adv • Notice that the AdvP rule specifies that the modifier of the HEAD adverb is another AdvP. • We will never get trees of this form: Adverb Phrases (AdvPs) • To clear up the confusion, have a look at these two phrases (AdjP & AdvP): • In (a), the adverb very is the head of the adverb phrase, and the adjective yellow is the head of AdjP. • In (b), we have the same kind of headedness, except both elements are adverbs. Very is the head of the lower AdvP, and quickly is the head of the higher one. We have two adverbs, so we have two AdvPs – each has its own head. • Principle of Modification (revised): If an XP (that is, a phrase with some category X) modifies some head Y, then XP must be a sister to Y (i.e., a daughter of YP). • N.B. asymmetric relationship: AdvP modifies Adj, but Adj does not modify AdvP. Prepositional Phrases (PPs) • Most PPs take the form of a preposition (the head) followed by an NP: • a) [PP to [NP the store]] • b) [PP with [NP an axe]] • c) [PP behind [NP the rubber tree]] The PP rule appears to be: PP→ P N (to be revised) So, the rule for the PP looks like: PP→ P (NP) • Question: Is the NP obligatory in the PP? • There is some evidence for treating the NP in PPs as optional. There is a class of prepositions, traditionally called particles, that don’t require a following NP: a) I haven’t seen him before. b) I blew it up. c) I threw the garbage out. • If these are prepositions, then it appears as if the NP in the PP rule is optional.