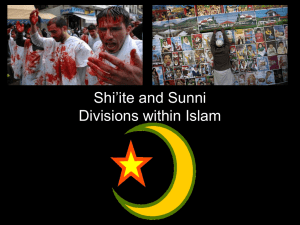

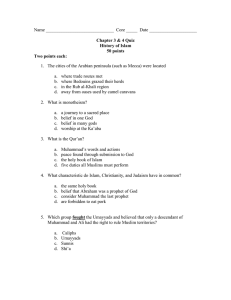

Sunni Shiite Split The Islamic religion emerged during the seventh century C.E. in the Arabian Peninsula, a region of the world dominated by Bedouin tribal culture. The harsh desert climate fostered a sense of cooperation while also encouraging shifting alliances and competition over scarce resources amongst rival tribes and clans. A burgeoning trade system, centered in the oasis town of Mecca, elevated one clan in particular, the Quraysh, to a level of wealth and prestige enjoyed by few clans throughout the Peninsula. It is under these conditions that Muhammad introduced the Islamic religion. Though his ideas were met initially with a great deal of resistance, Islam was eventually embraced by a significant portion of the population in the area. Following the death of Muhammad in 632 C.E., the fledgling Islamic community faced a crisis of succession which caused a significant rift among its members. When forced to decide who among this new community would succeed the prophet as their political and spiritual leader, several conflicting ideas surfaced regarding the qualifications that would be required of any such person. Along with religious ideology, political aspirations among various members of the Islamic community played a significant role in this debate. The family of the Prophet, or Banu Hashim, as they were referred to by the Islamic community, endorsed leadership from within the direct lineage of Muhammad. Supporters of this claim came to be known as the Shi’atu Ali, or the Shi’a. Contrarily, the powerful Quraysh clan wished to regain control over Mecca, as well as the Islamic community as a whole. Those Muslims who adhered to this idea became known as the Sunnis. This political and religious friction was further enhanced by the personal hostilities between leading members of the community. Early political decisions favored the Quraysh clan, with the first three leaders, or caliphs, being from the various tribes of the Quraysh. When the Banu Hashim attempted to claim the caliphate, tensions flared between the two groups, with the ultimate result being the beheading of Husayn, the grandnephew of the prophet Muhammad. The aforementioned tensions caused the schism between these two sects of the Islamic faith. As a consequence of the various events which occurred amongst the rival political factions, the Shi’ites developed a doctrinal and ideological foundation for their pre-existing sect. Consequently this rift, which initially called into question the issue of politics and leadership, developed into a theological divide. Starting in the early 5th century, the Quraysh clan of Mecca shrewdly manipulated the existing religious beliefs of the Bedouin people in order to consolidate their own political power. The pre-Islamic religious beliefs included the worship of a myriad of idols representative of tribal gods and nature spirits. In a culture whose religion incorporated pilgrimages and idol worship, the Quraysh recognized that those clans who controlled access to the various shrines held a clear advantage over other clans. With this knowledge, the Quraysh embarked on a mission to collect “…all the idols venerated by neighboring tribes – especially those situated on the sacred hills of Safah and Marwah” (Aslan, 25). After obtaining these idols from the surrounding areas, the leaders of the Quraysh clan transferred them to the Meccan religious shrine, the Ka’ba. By doing so, the Quraysh ensured a steady movement of pilgrims in and out of the city. As with all other shrines, the Ka’ba was considered to be sacred ground and therefore fighting was strictly prohibited in or around the area. The ultimate consequence of both, the increase in pilgrimage and the prohibition of fighting in the region, is that Mecca became a major trading center in the Arabian Peninsula. The Quraysh benefited from this situation economically by levying a tax on all those merchants who wished to trade there (Wolf, 332). Their control over the Ka’ba enabled the clan to dominate the political and economic life in Mecca until the introduction of Islam and Muhammad’s subsequent conquest of the city in 630 C.E. Muhammad was born into the Hashim tribe, one of the poorer tribes of the Quraysh clan, sometime during the late 6th century. He was orphaned by the age of six, and therefore considered an outcast in a society defined by kinship ties. Despite these obstacles, he was able to rise in Meccan society through his trade contacts and his marriage to the wealthy widow, Khadijah. Muhammad was raised by an uncle, who allowed him to assist in his flourishing caravan business. While on these trading expeditions, Muhammad came into contact with the various religious traditions of the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern regions. Consequently, he was familiar with the monotheistic traditions of the Jews and the Christians, upon which the religion of Islam is based. According to the Islamic faith, the message of Islam was revealed to Muhammad over a period of twenty two years, starting with The Night of Power and Excellence in 610 C.E. (Nigosian, 9). From the time of the first revelation, Muhammad attempted to spread the message of this new faith throughout Mecca. At the core of this new religious tradition was the idea that the community must be responsible for those who were considered outcasts in society; those who generally could not take care of themselves. This message was met with resistance by the wealthiest members of the Quraysh clan, as the religion implicitly attacks the excessive wealth of groups like the Quraysh. It was only through the protection of his uncle, whose influence in Mecca afforded him respect, and support of his wealthy wife, Khadija, that Muhammad was able to remain in Mecca unharmed. After the death of both his wife and uncle in 622 C.E., Muhammad was forced to flee the city of Mecca with his small community of followers. The Aws and Khazraj tribes from the small oasis town of Yathrib extended the invitation for Muhammad and his followers to live there in sanctuary. This journey from Mecca to Yathrib, later renamed Medina or the city of the Prophet, marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar and the official start of the Islamic religion (Hooker, 13). It is in Medina that Muhammad assumes political and religious control of what would be termed the Ummah, or the community of the faithful. Without the interference of the Quraysh, the Islamic religion is able to prosper, and the Ummah increases dramatically. The support that the Aws and the Khazraj, collectively known as the Ansar or helpers, gave to Muhammad and the Ummah is a crucial element when considering the foundations of the Islamic religion (17). This support, and the legitimacy it lends to the Ansar, will play a significant role in the political maneuvering regarding Muhammad’s successor in the years following his death. After building a solid foundation for the Islamic religion in Medina, the Prophet returned to Mecca with his army, both to convert his brethren there and to formally denounce the idols and gods of the pre-Islamic Bedouin tribal religions. After his army conquered the city in a swift, bloodless victory, Muhammad turned his attention to the Ka’ba. “With the help of his cousin and son-in-law, Ali, he lifted the heavy veil covering the sanctuary door and entered the sacred interior. One by one, he carried the idols out before the crowd, and raising them over his head, smashed them to the ground” (Aslan, 106). Though this spectacle was a definitive message regarding the beliefs and strength of the Islamic faith, Muhammad’s next action was even more emblematic of those beliefs. Rather than punishing those members of the Quraysh clan who had attempted to murder him, he instead granted them their freedom. He extended the invitation to join the Ummah, and they wholeheartedly accepted his message. For the next two years, up until the death of Muhammad, the Ummah continued to grow, both within the city of Mecca and beyond. Upon the death of Muhammad, the Quraysh predictably attempted to regain their control over the city of Mecca, as well as the larger Islamic community. Since they historically controlled the region for the two centuries prior to Muhammad’s conquest, the leading members of the Quraysh maneuvered in order to ensure that a member of their tribe would lead the Ummah thereafter. Additionally, it is important to note that the vast majority of Muslim converts within the city of Mecca had only converted in the last two years of the Prophet’s life. Thus, there were several prominent Meccans who felt little loyalty to the religion itself. The Quraysh therefore argued that it made more sense for the leader of this community to come from the preceding leaders of the city of Mecca, since the people of Mecca maintained pre-existing tribal connections to them. “The Quraysh laid their claim on the basis that theirs was the most experienced tribe in [the] diplomatic sense…”(Engineer, 5). There is some validity to this claim, both within the city of Mecca and in several other areas of the Arabian Peninsula that had come under the military control of the Ummah during the time. According to tribal customs, several new converts perceived their loyalty to the religion as being severed with the death of Muhammad, and it was common practice to uphold loyalty to a cause or a person only as long as that person was alive. In the absence of this loyalty, the Quraysh emphasized the need for experienced leadership which would be able to subdue those who wished to rebel against the new community. Again, they definitively promoted the idea that the men from their own leading clan would best fulfill this position. It was necessary, however, for the Quraysh to also promote leaders who would be recognizable to the larger Islamic community. “It quickly became clear that the only way to maintain both a sense of unity and some measure of historical continuity in the Ummah was to choose a member of the Quraysh to succeed Muhammad, specifically one of the Companions who had made the original Hijra to Medina in 622” (Aslan, 112). In an attempt to appease the community as a whole, as well as to promote their own political interests, the Quraysh pushed for the recognition of Abu Bakr as the first successor to the Prophet, commonly referred to as the Caliph. This selection was based on the generally acknowledged facts that Abu Bakr was one of the first Meccans to convert to the religion, was with the Prophet during the Hijra, and regularly traveled with him. Moreover, the responsibility of leading the important prayers was bestowed upon Abu Bakr by Muhammad himself in the last few weeks of his life. These attributes imparted Abu Bakr with the legitimacy sought by the pious members of the Ummah, while his prominent position as a member in the leading Muhajirun tribe of the Quraysh clan served to reestablish the clan’s control in the area. While the Quraysh of Mecca desired to assert their control over the Islamic world, the Ansar sought conversely to promote a leadership based in Medina. The Aws and the Khazraj tribes which made up the Ansar contended that the success of the early Islamic community rested primarily with the sanctuary provided by the city of Medina. It was during Muhammad’s time there that the adherents of the Islamic faith swelled in numbers. There, also, the Muslims were able to live in full accordance with the teachings of Muhammad and truly become a community of the faithful, or Ummah. The Ansar argued that while the Quraysh had persecuted the Muslims in the earliest stages of Muhammad’s revelations, the Ansar welcomed the Muslims. This, they believed, conferred the city with special status within the Islamic world, higher even than Mecca. As further argument, the Ansar point to the fact that the Islamic calendar does not start with the Night of Power and Excellence in Mecca, but rather with the Hijra, the journey of Muhammad and his companions to Medina (Esposito, 10). Therefore, when the prominent members of the Ummah met to select a leader to rule in Muhammad’s stead, the Ansar rejected the idea that the Quraysh were the logical and inevitable choice. Their support was placed firmly behind the Khazraj tribesman, Abu Thabit Sa’d b. Ubadah, “…in a clear bid to pre-empt the Quraysh…from cementing their leadership over the Ansar, and probably to assert or restore autonomy over their own city of [Medina] as the center of the new faith” (Crow, 45). The motivation for the Ansar does not lie solely in the need for recognition of their vital role in the early Islamic success. A Caliph chosen from amongst the population in Medina would certainly provide the city with an economic advantage. Just as the Quraysh had benefited from the control of the pre-Islamic pagan religion, so too would the Ansar benefit from an elevated status within the Islamic religion. Ultimately, however, the Ansar could not produce a leader who would have been acceptable to the Ummah which by this point was predominantly Meccan, and whose most powerful members belonged to the very clan they opposed for leadership. A third, and essential, player in these early political struggles for the Caliphate was the Banu Hashim, and more specifically Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali. With regards to the dominant Quraysh, Ali represented the only serious political opposition. Ali has the distinction of being one of the earliest converts to the religion, second only to Muhammad’s wife Khadijah. As a result, his piety and noble intentions regarding the Islamic community are never called into question, an advantage that the Quraysh, as a whole entity, never enjoyed. As one of the first converts, Ali, like Abu Bakr, accompanied Muhammad through all of the early triumphs and failures of the religious community. He therefore, according to the rationale used by the Quraysh for the selection of Bakr, would be acceptable to the Ummah as a result of his experience with regard to the teachings of Muhammad. Through his prolonged contact with Muhammad, he certainly gained an insight into how Muhammad settled disputes amongst fellow Muslims and why he favored one side over the other in various conflicts. He was well-versed in Quranic tradition, and “Ali was widely recognized for both his spiritual maturity and his military prowess” (Aslan, 116). The latter is important as a qualification for the leadership of this community. As stated previously, there were several groups throughout the Arabian Peninsula which sought to break ties with the Islamic religion and its political power base after the death of the Prophet. Any leader, from the Hashim, Ansar or Quraysh, would have to possess strong military prowess in order to subdue these rebellions. The Banu Hashim pointed to actions taken by Muhammad himself to legitimize the leadership of Ali. “He was regularly placed in charge of the Ummah in Muhammad’s absence and...only Ali was allowed to assist the Prophet in cleansing the Ka’ba for God” (Aslan, 116). From the Hashim point of view, these responsibilities were a clear indication that Muhammad himself wished Ali to lead in his stead. The former demonstrates Muhammad’s faith in Ali’s ability to politically lead the community of the faithful, while the latter is evidence of Muhammad’s conviction regarding the spiritual piety and strength possessed by Ali. It is, and has been, the contention of those who support Ali’s legitimacy that Muhammad verbalized his intentions for Ali to succeed him. “It is believed by the Shi’a that Muhammad took his son-inlaw and cousin, Ali, one of the very first Muslims, by the hand and said, ‘He, of whom I am the patron, of Him Ali is also the patron’” (Geaves, 101). This, they believed, occurred during one of Muhammad’s last pilgrimages to Mecca. Opponents of Ali discount the actuality of this event, claiming it to be merely propaganda for the political intentions of the Banu Hashim. They assert, rather, that Muhammad did not leave a successor and instead expected the community of the faithful to come to a consensus concerning the question of leadership. Political reasoning aside, proponents of Ali and the Banu Hashim contended that Islamic leadership must descend from within Muhammad’s lineage for religious purposes. Those who supported Ali’s leadership firmly believed that as a blood relative to the Prophet, his ability to divine the true meanings of Quranic verse would be vastly superior to that of other Muslims. “The Quran itself repeatedly affirms the importance of blood relations and endows Muhammad’s family – the ahl al – bayt – with an eminent position in the Ummah… (Aslan, 116). The Banu Hashim pointed to their inclusion within the holiest text of their religion as definitive proof of the legitimacy of their claim that the leadership of the Ummah remain within Muhammad’s family. The frequency with which the family of Muhammad is mentioned within the Quran is also seen by the Hashim as significant regarding the validity of their claims. “The total number of verses that mention special favour requested for and granted to the families of the various prophets by God runs to over a hundred in the Quran” (Jafri, 16). In addition to references in the Quran regarding their status within the Ummah, the family of the Prophet saw themselves as part of a historic pattern stretching all the way back to the family of Abraham. It was not uncommon for the families of important prophets to be granted leadership positions in their stead. “…A great many of the prophets and patriarchs of the Bible were succeeded by their kin: Abraham to Isaac and Ismail; Isaac to Jacob; Moses to Aaron; David to Solomon; and so on” (Aslan, 117). It is upon these religious arguments that the Islamic community began to polarize. In response to the claims of the Banu Hashim, the Quraysh argued vehemently that the Caliph, once selected, would fulfill a purely secular role for the Ummah. Their prime argument against the religious claims made for Ali’s leadership was that “the successor to the Prophet could not be another prophet or nabi…as it had already been made known through divine revelation that Muhammad was the Seal of the Prophets” (Daftary, 34). While only a minority of those who supported the Banu Hashim actually espoused the idea that Ali, or any other relative, would actually be a prophet, the urgency with which the Quraysh argued this fact convinced a majority of leading members within the Ummah to disregard Ali’s claims to the Caliphate. The Quraysh also exploited the tribal sentiments of the people in the Arabian Peninsula. “Among the Arabs, the chieftaincy of a tribe is not hereditary, but elective; …all the members of a tribe have a voice in the election of a new chief” (Nadwi, 74). In fact, the Arabs had a longstanding disdain for the hereditary governments in the Empires which surrounded them. The Quraysh therefore asserted that leadership from within the family of the Prophet would necessarily lead to a hereditary line of political leadership; one that would attempt to control the teachings of the religion as well. They instead presented the Ummah with their choice of leadership, Abu Bakr, who rejected the idea of either a hereditary or religious caliphate. “As far as Abu Bakr was concerned, the Caliphate was a secular position that closely resembled that of the traditional tribal Shaykh – ‘the first among equals’ – though with the added responsibility of being the community’s war leader…and chief judge” (Aslan, 113). By aligning the job of the Caliph with that of the former tribal Shaykh, Abu Bakr put himself in a position of advantage over all other potential candidates. At the time of Muhammad’s death, Bakr had distinguished himself as a capable military leader, a respected member of both the Meccan and Medinan communities, and as a pious and honest man. He was also one of the oldest members of the original converts to the Islamic religion. “The chiefs or the [shaykhs] in the North had always been elected on a principle of seniority in age and ability in leadership” (Jafri, 12). Bakr clearly exemplified all of the traits demanded by the traditional leadership position in tribal culture. It was only natural to deduce, then, that those qualities made him an excellent candidate for the position of Caliph as well. Although the Quraysh emerged victorious though this maze of political wrangling, the instatement of Abu Bakr as the first Caliph did not bring an end to the question of legitimacy and leadership. Within the Arabian Peninsula, there were a myriad of groups who bristled under the control of the Quraysh clan. The Ansar, in particular, did not support the selection of Abu Bakr. Ali also did not formally recognize Abu Bakr as the Caliph until six months passed (Crow, 49). Each group possessed their own reason for resisting the leadership which had been imposed on them. Although Abu Bakr himself proved to be a competent and capable leader, his connection to the Meccan aristocracy caused people great concern. There were several disenfranchised groups who felt that a continued leadership from the Quraysh family would lead to the same socioeconomic situation that existed in that region before the introduction of the Islamic religion. Their fear was such that the Shi’a gained popularity and support throughout the two years of Abu Bakr’s reign as Caliph. Ali, although disappointed at the decision to bypass him in favor of Bakr, had other reasons for his opposition to Bakr’s leadership; reasons stemming from personal frictions between the two men. As members of the larger Islamic community, Ali and Abu Bakr were viewed as respected leaders and early Companions of the Prophet. Personally, the two men were on less than harmonious terms. The tensions between these two men stemmed initially from an incident known as “The Affair of the Necklace.” According to the story, Muhammad’s wife, Aisha, went to a previous encampment to retrieve a lost necklace while accompanying Muhammad on a military expedition. The following morning, she arrived at the new camp accompanied by a young man. As would be expected in any patriarchal society, Aisha’s fidelity was called into question (Ahmed, 46). Abu Bakr, the father of Aisha, immediately came to the defense of his daughter. Contrarily, Ali asserted that whether or not she was guilty did not matter. What did matter, in his opinion, was that her reputation after the incident would tarnish the reputation of Muhammad. Aisha was ultimately cleared of any wrongdoing, but this incident caused a personal rift between Ali and Abu Bakr. This rift intensified as a result of Abu Bakr’s actions as Caliph. An early action taken by Bakr was to disinherit Muhammad’s family from the money and property that Muhammad had amassed during his lifetime. This Bakr did by recalling a conversation in which Muhammad stated, “We [the Prophets] do not have heirs. Whatever we leave is alms” (Aslan, 119). This left the Banu Hashim without the means to support their growing tribe. During Muhammad’s lifetime, he had strictly forbidden members of his family to accept alms. He had argued that accepting it would tarnish the religious purity of the family. After Bakr disinherited the Banu Hashim, he informed them that they were entitled to accept alms. “In the view of the Banu Hashim…Abu Bakr thereby demoted [them] from their rank of religious purity…” (Crow, 63). This attempt to reduce the growing support for the family of Muhammad actually had the opposite effect. Several groups, whose support initially favored continued rule by the Quraysh, saw Bakr’s actions as an affront to Muhammad’s family and therefore to Muhammad himself. Sensing that the general populace was now in great support of Ali as a leader, Abu Bakr pre-empted a loss in Quraysh power by naming his own successor, Umar. Although seen by some within the community as another attempt to usurp the power that rightfully belonged to the Banu Hashim, the rule of Umar was largely uncontested. During his ten year reign as Caliph, Umar attempted to heal the rift that Abu Bakr’s actions created between the Quraysh and the Banu Hashim. Nevertheless, “Umar continued to uphold, as a matter of religious dogma, the contention that prophet hood and the Caliphate should not reside in the same clan” (Aslan, 123). During this time, Ali patiently awaited his opportunity to eventually lead the Ummah. It was not until ten years later, with the selection of Uthman as Caliph, that hostilities emerged again between the Shi’a and the Sunnis. The selection of Uthman was made under the guise of a shura, or a meeting designed to allow leading members of the community reach a consensus. In reality, those leading members who were present at the shura were predominantly from the wealthy ranks of the Quraysh clan. Those present had the choice of two men for possible leadership, Ali and Uthman. “A wealthy member of the Quraysh clan…Uthman was a Quraysh through and through….He was, more than anything else, the perfect alternative to Ali: a prudent, reliable old man who would not rock the boat” (Aslan, 124). His selection as Caliph enraged the supporters of Ali. Moreover, Uthman proved to be a wholly impious, corrupt and covetous leader. He waged wars of expansion not for the benefit of enlarging the empire and the community of the faithful, as others had done. Rather, his motivation was economic, as he sought to increase the treasury of the Caliphate. Additionally, “[Uthman] placed Meccans, particularly relatives and members of his own family, in key positions such as provincial governorships to strengthen and control the Islamic state” (Nigosian, 19). During his short time as Caliph, Uthman alienated nearly everyone within the Islamic community. Resentment for his policies and greed became firmly entrenched and resulted in his assassination in 656. This violent act was committed by Egyptian Muslim rebels, and they were politically linked to the Shi’a whose support had increased significantly throughout Uthman’s reign as Caliph. The assassins themselves did not necessarily steadfastly support the aspirations of the Banu Hashim on the basis of religious ideology, but they demanded the removal of Uthman and his clan as a political necessity. This was not an uncommon position for Muslim converts to hold during the reign of Uthman, and “[the Shi’a] attracted malcontents who for various reasons were dissatisfied with the ruling house of the Umayyads…” (Nigosian, 48). The increased support the Shi’a received from these groups was certainly desirable, in light of their prior defeats. By the time of Uthman’s assassination, Ali and the Banu Hashim had gained enough political backing to take control of the Caliphate. In the days immediately following the assassination, the Egyptian rebels remained in Mecca and insisted upon the immediate designation of the fourth caliph (Muir, 244). After some hesitation, mainly stemming from the violent manner in which his predecessor was removed, Ali accepted the Caliphate. By taking on the caliphate in the wake of Uthman’s assassination, the first perpetrated by a fellow Muslim, Ali placed himself in command of a highly volatile situation. The Ummayad family, from which Uthman hailed, was considerably angered by the situation. More so, the remaining family members desired to maintain control of the Caliphate, arguing that the reign of Uthman and his efforts to place family members into positions of bureaucratic authority had legitimately transferred the Caliphate to their clan. Sensing political backlash and possible violence, “Ali decided to move the centre of the caliphate to [Kufa], a town in Iraq where he had more support” (Geaves, 103). From this power center, Ali attempted to restore order to the Muslim community. Although most people within the Ummah agreed with Ali’s policies, especially his decision to remove several of Uthman’s family members from their government posts, his decision to grant amnesty to Uthman’s assassins led to further political tensions. Ali’s reasoning for pardoning those who were complicit in the bloodshed was reminiscent of Muhammad’s decision to grant reprieve to those in Mecca who had persecuted the early Islamic community. Ali reasoned that any effort to seek vengeance on the assassins would perpetuate the tribal hostilities which existed before the onset of Islam. Unfortunately for Ali, his attempt to avoid these hostilities was not embraced in the same manner as were Muhammad’s. The Umayyad clan perceived this amnesty as proof of Ali’s own complicity in the affair. They used this suspicion to promote the idea that their family should still rightfully control the Caliphate. Shortly after Ali’s decision, the Umayyad proclaimed a member of their clan, Mu’awiyah, to be the fourth Caliph. Implicit in this action was the refusal to recognize Ali as a legitimate Caliph. Ali’s actions with regard to Uthman’s assassins “not only enraged the Ummaya [family], they paved the way for Aisha [Abu Bakr’s daughter] to rally support in Mecca against the new Caliph by pinning him with the responsibility for Uthman’s murder” (Aslan, 130). Presumably still bitter with regards to “The Affair of the Necklace, Aisha sought to undermine Ali’s authority. Aisha maintained powerful connections to prominent members in the Quraysh clan and thus was able to gain considerable support in her effort to remove Ali from power. Arguing from an ideological standpoint originated by her father, she reinforced the idea that the Caliphate must be kept separate from the Banu Hashim. She appealed to older sentiments that the future of Islam would be seriously compromised in the event that the family of the Prophet was able to maintain control over the political realm of the Islamic community. At the core of her arguments against Ali, though, was her insistence that he was a part of Uthman’s assassination. She was able to raise a considerable army under this premise, which she brought north toward the new capital of Kufa. “After driving out the governor who represented Ali, Aisha set up her headquarters in Basra, and with her two allies, Talha and al-Zubair, members of the Quraysh tribe like herself, she continued her campaign of information, negotiation, and persuasion through individual interviews and speeches in the mosques, pressing the crowds to support her against the “unjust” caliph (Mernissi, 7). She and her faction marched against Ali’s forces in 656 in what became known as the Battle of Bassorah, or the Battle of the Camel. Although she and her army were able to inflict serious damage on Ali’s forces, she was ultimately unsuccessful. In accordance with Muhammad’s teachings, however, Ali pardoned those who took part in this rebellion as well. The Battle of the Camel was followed by a succession of military conflicts and political maneuvers which had lasting implications for the Shi’a control of the Caliphate. While Ali was handling the rebellion led by Aisha, Mu’awiyah was consolidating political control and amassing his own army in Damascus. Mu’awiyah’s actions necessitated that Ali turn his attention immediately toward this new threat. At the Battle of Siffin, Ali was on the verge of successfully putting down this rebellion as well, when Mu’awiyah signaled a desire to surrender and meet for arbitration. Although Ali was suspicious of Mu’awiyah’s actions, he could not refuse to acknowledge the surrender, a point that had been laid out by Muhammad in the Quran. Ali’s decision to meet for arbitration enraged some of his supporters, the Kharijites, who defected and assembled their own army. While the arbitration was taking place, Ali was forced to confront his former allies in a considerably bloody battle. Ali returned from the battle to hear the outcome of the lengthy arbitration. It was declared that the murder of Uthman was worthy of retribution, an idea that legitimized the actions of Mu’awiyah. Although the arbitration did not specifically state that Ali was to blame for the assassination of Uthman, this outcome “did serve to delegitimize Ali in the eyes of some of his supporters” (El-Soufi, 3). This was a significant blow for Ali, especially in light of the fact that Mu’awiyah had taken advantage of the lengthy arbitration process and used the time to reassemble his military forces in Damascus. The morning before Ali was able to bring the remnants of his army against Mu’awiyah, however, a Kharijite murdered him with a poisoned sword. With his death, Ali’s sons Hasan and Husayn were left to further the Shi’a cause and reinstate the Caliphate under the name of the Banu Hashim. Hasan, as the elder of the two brothers, was expected by his Shi’a supporters to forcibly remove Mu’awiyah. Although there was significant pressure on him to do so, Hasan opted instead for a cease-fire agreement. He understood that it would not be possible to defeat Mu’awiyah and his powerful Syrian army with his own scattered forces. By agreeing to a cease-fire, Hasan furnished the Shi’a with the time necessary to consolidate their support as well as to build up an adequate military. This armistice endowed Mu’awiyah with a legitimate claim to the Caliphate, but was also accompanied by a promise on his part to allow the Muslim community to decide upon his successor by consensus. The possibility of a restoration of political power appeased the Banu Hashim and its supporters for the remaining nineteen years of Mu’awiyah’s reign. By the last years of his life, however, it became increasingly clear that Mu’awiyah intended to transform the Caliphate into a dynasty, not unlike those of the neighboring Sassanid and Byzantine Empires. In an effort to remove himself from both the power centers of the Shi’a and the other prominent members of the Quraysh clan, Mu’awiyah designated Damascus as his capital city. There he encouraged intellectual and cultural pursuits, making the city into a center of great learning and civilization (Simons, 150). Throughout his reign, he centralized his political control and enlarged the Islamic Empire. His power went largely uncontested, and he therefore cemented his intention to establish an official Umayyad dynasty by naming his own son, Yazid as his successor. By doing so, he reneged on his initial promise to put the question of the Caliphate before the Islamic community. Understandably, the appointment of Yazid as Caliph was not embraced by all groups within the Muslim community. “That sentiment was perfectly embodied by the heterogeneous coalition of the Shi’atu Ali, who had little else in common save their hatred of the Banu Umayya and their belief that only the family of the Prophet could restore Islam to its original ideals of justice, piety, and egalitarianism” (Aslan, 175). In response to Yazid’s appointment as Caliph, the Shi’a supporters in Kufa encouraged Ali’s younger son Husyan to join them there. Yazid regarded this invitation as an implicit threat against his sovereignty, and moved swiftly to preempt any rebellious activity. His chief general, Ubaydu'llah ibn Ziyad, was sent to the city of Kufa to ensure that the Shi’a did not attempt to engage in activities that would be subversive to his reign (Hooker, 2). Additionally, a military contingent was sent to intercept Husayn and his fellow travelers. Traveling with a band of mainly women and children, Husayn found himself and his followers in a precarious situation after Yazid’s forces surrounded them. This group was surrounded in Karbala, a town close to Kufa. In an effort to force Husayn’s retinue to surrender, the Caliph’s troops blocked all access to their water and food supplies. Thus, Husayn’s group of supporters was left to face dehydration, starvation and eventually death. According to Shi’a sources, Husayn charged into the line of enemy forces, although he was fully aware that he would not survive the attempt. Islamic scholars argue that he intentionally martyred himself, knowing that it was his purpose and destiny; as he commenced the attack, Husayn is reported have said, “We are for God, and to God shall we return” (Aslan, 173). His actions are regarded by the whole of the Shi’a community as the ultimate sacrifice, and as a reflection of Husayn’s dedication to preserving the integrity of the Muslim community as a whole. Following the encounter with Husayn and his followers, Yazid’s forces defamed the integrity of the Banu Hashim and their Shi’a supporters. Central to this humiliation was the beheading of Husayn. Additionally, “Husayn's followers were decapitated, and the women and children were led back to Yazid in chains” (Hooker, 4). Before bringing the captives to Yazid in Damascus, however, the soldiers first entered into the city of Kufa. There, before the Shi’a supporters, the heads of Husayn and others were paraded through the center of the city. The women and children were also led in chains throughout the city, including Husayn’s sister, Zaynab, and his son, Ali. This humiliating demonstration, along with the death of Husayn, enraged the Shi’a supporters, and firmly established an already present resentment of the Umayyad rulers. For the Shi’a, “[Husayn’s] martyrdom epitomized the essential illegitimacy of the Umayyad rulers, who contrasted unfavorably with his pious lifestyle” (Cook, 58). Though the Shi’a had repeatedly attempted to reach compromises with the remainder of the community up to this point, these efforts ceased with the beheading of Husayn. From this point forward, the Shi’a saw themselves as distinctly separate from the Sunni majority who supported the Umayyad. In fact, from the time of Husayn’s martyrdom to the modern period, “…the Shi’a would view the mainstream of Sunni Islam, although ostensibly successful and the majority of Muslims, as representative of an illegitimate and degenerate empire that could never be the true people of God” (Geaves, 107). It is important to note that the actions of Yazid and his military forces were not endorsed by the Sunni majority, and in truth most Sunnis were horrified by the manner in which the family of the Prophet had been treated. Nevertheless, this event created a rift between these two groups that persists even to the present. Though these groups initially differed with regards to political ideologies alone, the events at Karbala set into motion a transformation of Shi’a theology. Central to the developing Shi’a theology is the importance of martyrdom, with the primary emphasis being placed on the martyrdom of Husayn. “The 10th of Muharram, the anniversary of his martyrdom, is a time of profound mourning and demonstrations of loyalty to al-Husayn and the other Imams that followed him” (Cook, 58). This “cult of martyrdom,” as it is referred to, stems from the belief that these martyrs suffered and died in order to preserve the integrity of the Islamic religion. Their sacrifice was also seen as a reflection of the suffering that the early Islamic community experienced in Mecca and during the Hijra. “Based on the way in which the events of Karbala were interpreted, there developed in Shi’ism a distinctly Islamic theology of atonement through sacrifice, something alien to orthodox, or Sunni, Islam” (Aslan, 179).The Shi’a, therefore, attempt to emulate that suffering and sacrifice during the mourning period that accompanies the anniversary of Husayn’s martyrdom. “The climax of this mourning period is the celebration of a passion play, culminating on the tenth day of Muharram with a re-enactment of the suffering and death of Husayn” (Nigosian, 127). In areas of the world with a significant Shi’a population, the people demonstrate through the streets and engage in self mutilation. Also central to the Shi’a theological tradition that emerged after the split is the figure of the Imam. According to Shi’a ideology, an Imam is related to the Prophet and therefore the spirit of Allah is housed within that person. As such, the Imam alone is spiritually capable of interpreting Qurani scripture As the Shi’a believe, “prophets and imams are sinless and infallible and therefore cannot err” (Nigosian, 46). For the Shi’a, the Imam is an important figure, and these Shi’a Imams are seen as having divine power. Contrarily, the Sunni Imam is merely the person who leads the prayers at the mosque. The Sunni majority regards the Shi’a interpretation of the Imam as heretical doctrine, since the Quran does not explicitly create an ideological foundation for a divine Imam. These differing ideas regarding the Imams and their role in Islamic life have led to widespread persecution of Shi’a Muslims, as well as the Imams themselves. The Sunni were involved with “…interning members of the Prophet’s family during the ninth century or keeping them effectively under house arrest. Alternatively, descendants of Muhammad who fled to distant corners of the empire…or to territories outside the political control of the caliphate were assassinated” (Cook, 60). Martyrs aside, the Shi’a suffered continuously throughout Islamic history, both politically and physically. During the time from the inception of Islam until the present, there has only been one major Shi’a dynasty, controlled by the Seljuk Turks. The Shi’a have also been exploited by various groups who had aspirations for political power. The Abbasids in the 8th century, for example, sought the support of the Shi’a in their attempt to overthrow the Umayyad Caliphate. They claimed legitimacy by linking their leader, Abu al-Abbas, to a cousin of the Prophet Muhammad. With the help of the Shi’a, thousands of the Umayyad political leaders and advisors were slaughtered or removed from power. “Once in power, the Abbasids found the support of their erstwhile allies a problem and repressed the Shi’a with a significant degree of brutality. The key players who had participated in the rebellion against the Umayyads amongst the Shi’a were murdered” (Geaves, 108). It is this perpetual political and physical suffering that strengthened the rift between the Sunni and Shi’a sects of the Islamic religion. During the years immediately following the death of the Prophet Muhammad, the political maneuvering that occurred in an effort to gain control of the Islamic community laid the foundation for an ideological schism. The Shi’a, though initially opposed to the majority Sunni population in a strictly political realm, came to see themselves as diametrically opposed to the Sunni in a theological manner as well. The events which unfolded during the political power struggles between the two groups cemented tensions and laid the foundation for a distinctive religious ideology. Works Cited Ahmed, Leila. Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992. Aslan, Reza. No god but God: The Origins, Evolution, and Future of Islam. New York: The Random House Publishing Group, 2006. Cook, David. Martyrdom in Islam. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Crow, Karim D., and Amad Kazemi Moussavi. Facing one Qiblah: Legal and Doctrinal Aspects of Sunni and Shi’ah Muslims. 1st. Singapore: Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd, 2005. Daftary, Farhad. The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990. El-Soufi, Denise. "Muawiya B. Abi Sufyan." Islamic Timeline. 12 Sep 1996. Princeton. 7 Apr 2007 <http://www.princeton.edu/~batke/itl/denise/muawiya.htm>. Engineer, Asghar Ali. "The Political Universe of Islam." Islam and Modern Age. Feb 2002. Rutgers. 9 Apr 2007 <http://www.andromeda.rutgers.edu/~rtavakol/engineer/politics.htm> Esposito, John L.. Islam: The Straight Path. 1st. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988. Geaves, Ronald. Aspects of Islam. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2005. Hooker, Richard. “Islam.” Shi’a. Washington State University. 17 Apr 2007 <http:// www.wsu.edu/~dee/ISLAM/SHIA.HTM>. Jafri, S. Husain M.. Origins and Early Development of Shi'a Islam. New York: Longman, 1979. Mernissi, Fatima. "Can a Woman Be a Leader of Muslims?." IRFI. 11 Mar 2007. Islamic Research Foundation International, Inc. 30 Mar 2007 <http://www.irfi.org/articles/ articles_401_450/can_a_woman_be_a_leader_of_musli3.htm>. Muir, Sir William. The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline And Fall from Original Sources. Piccadilly: The Religious Tract Society, 1891. Nadwi, S. Abul Hasan. "Ali During the Reign of Caliph Abu Bakr." 18 Apr 2004. The Canadian Society of Muslims. 17 Mar 2007 <http://muslim-canada.org/ali_abubakr.html>. Nigosian, S.A.. Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004. "Shi'a Islam." 9 Aug 2000. Washington State University. 30 Mar 2007 <www.wsu.edu/~dee/ TEXT/111/unit6pt2.rtf>. Simons, Geoff. Iraq: From Sumer to Saddam. 2nd. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996. Wolf, E.. "The Social Organization of Mecca and the Origins of Islam." Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 7(1951): 329-356