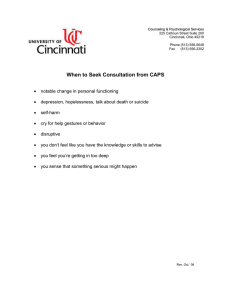

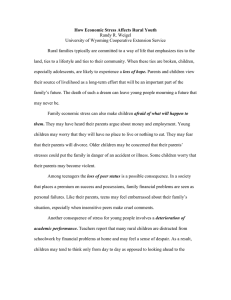

Name Here Project 2 1 In order to ensure your assessment is correctly identified, The author hasand notdeclaration authorised below any further reproduction the information must be copied and or communication of this material. pasted on to the title page of each written assessment. You must enter your own details prior to submission. Portions of text have been removed from this preview. STUDENT DETAILS ACAP Student ID: ID HERE Name: Name Here Course: Bachelor of Counselling ASSESSMENT DETAILS Unit/Module: Project 2 Educator: Name Here Assessment Name: Literature review Assessment Number: 1 Term & Year: Word Count: 2402 (excluding abstract & headings) DECLARATION I declare that this assessment is my own work, based on my own personal research/study . I also declare that this assessment, nor parts of it, has not been previously submitted for any other unit/module or course, and that I have not copied in part or whole or otherwise plagiarised the work of another student and/or persons. I have read the ACAP Student Plagiarism and Academic Misconduct Policy and understand its implications. I also declare, if this is a practical skills assessment, that a Client/Interviewee Consent Form has been read and signed by both parties, and where applicable parental consent has been obtained. Name Here Project 2 Self-Harm Among Rural Australian Adolescents: A Literature Review Name Here Australian College of Applied Psychology Term 3, 2017 2 Name Here Project 2 3 Abstract This review examines the current literature regarding self-harm among rural Australian adolescents. The objective was to determine the vulnerabilities and impacts of self-harm among adolescents in rural Australian communities and explore potential treatment interventions. Twenty-five papers were selected from approximately 438 abstracts. Limited data were found reflecting self-harm, specifically among adolescents residing in rural communities, indicating that further research is needed. The literature revealed that the prevalence of self-harm among adolescents in general ranges from 4-18% and is almost double that among rural populations. Various risk-factors were identified as well as significant risk of suicide among self-harmers. Several factors were also identified as barriers This treatment portion offor text has been removed from this preview. to receiving adequate self-harming behaviour among rural adolescents. The The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. literature suggests that Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) and family therapies, within school-based initiatives, as potentially effective interventions for this population. The proposed intervention offers a 16-week DBT program, alongside a psychoeducational workshop for parents, delivered within a school setting. It also recommends mental health promotion within rural communities and schools. Name Here Project 2 4 Self-Harm Among Rural Australian Adolescents: A Literature Review Adolescent self-harm (ASH) is a significant health concern in Australia (Guerreiro et al., 2013). Prevalence rates range from 4-18% among the general adolescent population with many of these individuals later attempting suicide (Freeman et al., 2016). This review portion of text has been in removed from thiswhere preview. explores self-harmThis among adolescents residing rural Australia, the prevalence of The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. self-harm and suicide is almost double than urban Australia (AIHW, 2014). This review explores the literature regarding ASH in rural communities, including, prevalence, riskfactors, consequences and needs of this group. It further explores evidence-based treatment interventions that may be effective in supporting youth resorting to self-harm. A comprehensive approach, incorporating group DBT and family psychoeducation, implemented within rural schools, is predicted to be a viable intervention for self-harming among rural Australian adolescents. Definitions Self-harm refers to deliberate damage to one’s own body, without intent of dying, through self-injurious behaviour (De Kloet et al., 2011; Freeman et al., 2016; Guerreiro et al., 2013; Hawton et al., 2009). Deliberate self-harm behaviours include, self-cutting, jumping off This portion of textillicit has been removed from this preview. heights and ingestion of prescribed, or non-ingestible substances (Madge et al., 2008, as The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. cited in, Guerreiro et al., 2013; Healey, 2014). For the purposes of this review, the term selfharm will be used to describe any deliberate harm to self without intent of death. This review refers to experiences of self-harm in the context of adolescents, specifically aged 13-18, residing in rural areas of Australia. ‘Rural’ refers to individuals living in regional and remote geographical locations, both of which can be included in the loose definition of ‘rural’ (Kõlves et al., 2012). The review explores the literature within this context. Name Here Project 2 5 Database Search A literature review was undertaken to examine self-harm among rural Australian adolescents. Twenty-five papers were selected from approximately 438 abstracts using EBSCO Host, Google Scholar and internet searches. Articles were chosen on the basis that they were; reliable research, relevant to the rural Australian context, referred to adolescents and published in the last decade. Search criteria included: ‘Self-harm in adolescents in rural Australia’; ‘Rural adolescent mental health’, ‘Self-harm in rural areas Australia AND adolescents’ and ‘DBT for self-harm’. Self-harm’ was also searched among E-book databases which yielded two suitable results. This literature was reviewed by the author, resulting in the selection of those appearing in this paper. Review of the Literature on Self-Harm Prevalence Prevalence rates for self-harm among adolescents vary from 4% within the general population to 60–80% among hospital inpatients (De Kloet et al., 2011). Numerous studies report results ranging from 12-18% for adolescents in general (Freeman et al., 2016; Hawton et al., 2009; Ougrin et al., 2012). These varying results may reflect the samples, measures, This portion of text has been removed from this preview. definitions of self-harm, the secretive nature of the behaviour and disparities in the way The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. hospitals record data (Fox, Hawton & Fox, 2004). Freeman et al., (2016) assert that it is difficult to obtain accurate prevalence rates for self-harm. Self-harm data are much more limited for those in rural communities. In rural areas, the prevalence is documented to be higher than the general population, increasing with remoteness (NRHA, 2017). The National Rural Health Association (NRHA) undertook studies, in 2009 and 2017, which showed that in a one-year period there were 191 hospital admissions in regional areas and 231 in remote areas following self-harm, as compared to Name Here Project 2 6 125 in major cities. This suggests that rates of self-harm are almost twice as likely in rural adolescent populations as compared to the general population. Risk-Factors There are a multitude of risk-factors documented to predispose adolescents to selfharm. Most notably, psychopathology has been found to be highly predictive of self-harm. Studies suggest that at least 87% of adolescents who self-harm have coinciding diagnoses including depression, post-traumatic stress and personality disorders (De Kloet et al., 2011; Freeman et al., 2016; Guerreiro et al., 2013; Hawton et al., 2009; Madge et al., 2011; Ougrin et al., 2012). Furthermore, previous suicidal behaviour is one of the most significant predictive factors for self-harm (Shaffer & Pfeffer, 2001, as cited in, Guerreiro et al., 2013). This suggests that adolescents are resorting to self-harm due to enduring immense psychological burden. Specific individual characteristics may be risk factors for self-harm. Such traits include; poor problem-solving and emotion regulation skills and withdrawing from social portion removed thisThis preview. support (Stanford This et al., 2009, of as text citedhas in, been Guerreiro et al.,from 2013). suggests that these The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. adolescents require social support and the development of new coping skills. Family life is another influencing factor. Difficulties with parental relationships are common concerns for adolescents (De Kloet et al., 2011; Hawton et al., 2009). Many studies have linked parental criticism, unresponsiveness, lacking support and rejection with selfharm, which is frequently preceded by parental conflict (Scott, Diamond & Levy, 2016). Again, this suggests adolescents may be lacking support and developing more supportive family relationships may be a protective factor for self-harm. Scott et al. (2016) suggested that family involvement in treatment would support positive outcomes by addressing this risk-factor. Name Here Project 2 7 In rural areas, specific risk-factors affect young people including, unemployment, increased availability of lethal means and barriers to accessing mental health services. These barriers include, lacking anonymity, self-reliance being culturally embedded, and stigma This portion text has been removed from this preview.particularly associated with mental illnessof (Boyd et al., 2007). Personal vulnerabilities The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. magnified by living rurally include, loneliness, lack of community understanding and untreated depression (NRHA, 2009; NRHA, 2017). These issues may increase isolation and reduce availability of support. It is evident there are a combination of factors that may predispose adolescents to self-harm including, psychological disorders, personal characteristics, family difficulties, as well as additional factors affecting rural communities. Social and Psychological Impacts There are significant and detrimental consequences for ASH. The most serious implication highlighted across the literature was the increased risk of suicide, with at least 70% of adolescents who had self-harmed having also attempted suicide (De Kloet et al., 2011; Freeman et al., 2016; Guerreiro et al., 2013; Hawton et al., 2009; Ougrin et al., 2012). In fact, Bennardi et al. (2016) highlighted that repeated self-harm is the strongest suicide riskfactor. Considering rural communities, where adolescent suicide occurs almost twice as often than in urban areas (NRHA, 2017), addressing self-harm may also reduce suicide prevalence. Needs Various needs have been identified for rural ASH arising from the risk-factors and impacts. These include addressing poor emotion regulation skills, difficult family relationships and barriers to utilising treatment services. Freeman et al. (2016) highlighted that developing effective coping strategies and emotion-regulation skills is needed for adolescents. An appropriate intervention should include such skill development. As family difficulties are a contributing factor of ASH, there is consensus that family involvement within treatment interventions may be useful (Hawton et al., 2009; Scott et al., This portion of text has been removed from this preview. The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. Name Here Project 2 8 2016). Research suggests that adolescents more commonly seek support from family and friends as opposed to mental health professionals (Hernan et al., 2010; Rughani, Deane & Wilson, 2011). This preference was also observed by Ougrin (2012), who asserted that wider systems, such as school and family, play important roles in addressing ASH. The notion that family and peers are a preferred support system for adolescents and family difficulties can be This involving portion ofthem text has been removed from this preview. a risk-factor for ASH, in treatment interventions could enhance benefits. The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. The barriers affecting treatment utilisation among rural youth such as stigma, poor mental health literacy (Boyd et al., 2007) and insufficient access to mental health services (AIHW, 2014; NRHA, 2009) require attention. Findings suggest that increasing mental health literacy and understanding of the benefits of seeking help may increase the use of services (Rughani et al., 2011). It would therefore be important to ensure that intervention strategies seek to mitigate these barriers by de-stigmatising mental health, providing accessible services and improving mental health literacy. While these issues require attention, another factor is that limited literature exists regarding self-harm among rural adolescents and no interventions have been established as entirely effective for adolescents (Ougrin et al., 2012; Scott et al., 2016). Therefore, more research is required among this population to find effective treatments. Review of Interventions The evidence suggests various interventions that would be potentially effective in addressing self-harm. Trials of DBT and family therapies are yet to determine results among adolescent populations, however, have been found effective among adults (Ougrin, 2012). DBT is the recommended treatment for adults engaging in self-harm and has been widely used and tested (Andion et al., 2012; Boyce et al., 2003; Freeman et al., 2016; James et al., 2008; Low et al., 2001). There have been fewer studies however, adapting this treatment for use with adolescents al., has 2016; James et al., from 2008;this Ougrin et al., 2012). Due to This(Freeman portion ofettext been removed preview. The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. Name Here Project 2 9 the specific needs of adolescents, DBT programs for young people differ from standard adult approaches. Despite this, Muehlenkamp (2006) highlights that adapted versions of DBT with adolescents have been trialled (as cited in, Freeman et al., 2016). DBT has a variety of components. Interventions may include, individual psychotherapy and group skills training (Linehan, 1993, as cited in, Freeman et al., 2016). Core components include teaching emotion regulation, interpersonal skills, distress tolerance and mindfulness (Rathus and Miller 2002, as cited in Freeman et al., 2016; James et al., 2008). Adolescent adaptions of DBT, as recommended by Miller, Rathus and Linehan (2007) have incorporated additional components including; improving parent and adolescent communication; family skill-building; family therapies; shorter treatment length of 16Thismaterials portion offor text has been removedfor from this preview. weeks; and reworded greater applicability teenagers (as cited in, Freeman et The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. al., 2016). James et al. (2008) found marked improvements on all self-harm measures using an adapted version of DBT for female adolescents. Standard DBT appears to address the need for the development of coping skills among adolescents, while the additional components in adolescent versions attend to familial risk factors associated with self-harm. While there is growing evidence to support DBT as a viable intervention for ASH, some challenges need to be addressed (Freeman et al., 2016). These include; the need for consistency across studies in defining self-harm, treatment length and measures, incorporation of all DBT treatment components tailored for adolescents and longitudinal studies to determine efficacy long-term (Freeman et al., 2016). This suggests further clinical trials should be undertaken using consistent methods to determine efficacy among rural adolescents. Families also play a key role in treating ASH. Kerfoot et al. (1996) asserts that selfharm in adolescents is often associated with family dysfunction and therefore DBT Thisbeportion of text has been removed fromtherapies this preview. interventions should delivered in conjunction with family (as cited in, James et The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. Name Here Project 2 10 al., 2008). There are various avenues for achieving this such as, group psychoeducation for parents and family therapy to improve relationships (James et al., 2008; Scott et al., 2016). De Kloet et al. (2011) validates the importance of parental involvement in treatment due to family difficulties being a risk-factor for self-harm. Parents are increasingly included in treatments to target family dynamics linked to risk and protection from self-harm and increasing family cohesion (Diamond et al., 2014, as cited in, Scott et al., 2016). The evidence suggests that family involvement in the treatment of ASH has the potential to improve outcomes and addresses this risk-factor for ASH. In terms of implementation within a rural setting, other factors would need to be taken into consideration to address barriers to help-seeking. Boyd et al., (2007); Hawton et al. (2009); Fortune et al. (2008) assert that for adolescents, access to help is primarily schoolbased and Hawton et al. (2009); Hernan et al. (2010) suggest that school-based initiatives may offer the most potential for this population. Hernan et al. (2010) further suggest that health promotion strategies should promote school-based utilising family This portion of text has been removedinterventions from this preview. The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. involvement for adolescents. Therefore, a viable treatment intervention for self-harm, specifically adapted to adolescents residing in rural communities should incorporate DBT with family involvement, delivery within a school setting and health promotion initiatives in order to address the identified needs of this group. Proposed Intervention A recommended intervention program that is evidence-based, and addresses the needs of rural adolescents who self-harm, would be most effective. Growing evidence suggests DBT is a promising intervention for ASH (Freeman et al., 2016). The proposed intervention incorporates three elements including, group DBT for adolescents, psycho-education for parents and implementation within a school setting. This portion of text has been removed from this preview. The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. Name Here Project 2 11 The DBT program would be adapted for adolescents. In addition to the inclusion of core components of DBT, the intervention would also include improving communication between adolescents and their parents, skills training for parents, 16-week treatment length and age appropriate materials (Miller, Rathus & Linehan, 2007, as cited in, Freeman et al., 2016). Furthermore, Boyd et al., (2007); Hawton et al. (2009); Hernan et al. (2010); Francis et al. (2006); Tormoen et al. (2013) suggest the delivery of ASH interventions should be school-based for enhanced effectiveness. These elements would be implemented to support the additional needs of adolescents. Additionally, family involvement is recommended as being predictive of enhanced success in treatment interventions for ASH (De Kloet et al., 2011; Scott et al., 2016). The literature suggests the incorporation of psycho-education for parents within interventions (De portion text Scott has been removed from this preview. Kloet et al., 2011;This James et al.,of 2008; et al., 2016). Hence, a parental psychoeducation The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. group would be included that would address topics such as; improving parent-adolescent communication (Miller, Rathus & Linehan, 2007, as cited in, Freeman et al., 2016) and increasing family cohesion (Scott et al., 2016). Incorporating family and school involvement within the intervention is likely to support treatment outcomes. While no specific intervention has proven effectiveness for treating rural ASH, by incorporating elements the literature suggests as effective for this population, there is increased potential for positive outcomes. Conclusion The aims of this review were to examine the literature regarding ASH within rural Australia. As this population has not been extensively studied, much of the data refer to Australian adolescents in general. However, some key considerations were identified for this population, including prevalence of self-harm being almost double, coupled with various barriers to treatment utilisation. The identified needs for this group included; development of Name Here Project 2 12 coping skills, family and school involvement within interventions, improving treatment access, reducing stigma and providing treatment options for rural adolescents. DBT was the This portion of text has been removed from trials this preview. recommended treatment amongst adult populations and some delivered positive The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. outcomes for adolescents, despite some challenges that need to be mitigated. In terms of providing DBT treatments for rural ASH, the literature highlighted that interventions should incorporate family involvement and be delivered within school-based settings to increase potential for benefit among this population. The proposed intervention offers a 16-week DBT program, alongside a psychoeducational workshop for parents, delivered within a school setting. It also recommends mental health promotion within rural communities and schools. In delivering an evidence-based and comprehensive intervention, self-harm may be addressed more effectively among these vulnerable Australians, as well as contribute to the existing literature. Name Here Project 2 13 References Andion, O., Ferrer, M., Matali, J., Gancedo, B., Calvo, N., Barral, C., & … Casas, M. (2012). Effectiveness of combined individual and group dialectical behaviour therapy compared to only individual dialectical behaviour therapy: A preliminary study. Psychotherapy, 49(2), 241-250. doi: 10.1037/a0027401 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2014). Suicide and Hospitalised Selfharm in Australia. Retrieved from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/b70c6e7340dd-41ce-9aa4-b72b2a3dd152/18303.pdf.aspx?inline=true Bennardi, M., McMahon, E., Corcoran, P., Griffin, E., & Arensman, E. (2016). Risk of repeated self-harm and associated factors in children, adolescents and young adults. This portion of text has been removed from this preview. The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 1-12. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1120-2 Boyce, P., Carter, G., Penrose-Wall, J., Wilhelm, K., & Goldney, R. (2003). Summary Australian and New Zealand practice guideline for the management of adult deliberate self-harm (2003). Australasian Psychiatry, 11(2), 150-155. doi: 10.1046/j.1039-8562.2003.00541.x Boyd, C., Francis, K., Aisbett, D., Newnham, K., Sewell, J., Dawes, G., & Nurse, S. (2007). Australian rural adolescents’ experiences of accessing psychological help for a mental health problem. Australian Journal Of Rural Health, 15(3), 196-200. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00884.x De Kloet, L., Starling, J., Hainsworth, C., Berntsen, E., Chapman, L., & Hancock, K. (2011). Risk factors for self-harm in children and adolescents admitted to a mental health inpatient unit. Australian & New Zealand Journal Of Psychiatry, 45(9), 749-755. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.595682 Name Here Project 2 14 Fortune, S., Sinclair, J., & Hawton, K. (2008). Adolescents’ views on preventing self-harm. Social Psychiarty & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(2), 96-104. doi: 10.1007/s00127007-0273-1 Fox, C., Hawton, K., & Fox, C. (2004). Deliberate self-harm in adolescence. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com Francis, K., Boyd, C., Aisbett, D., Newnham, K., & Newnham, K. (2006). Rural adolescents’ attitudes to seeking help for mental health problems. Youth Studies Australia, 25(4), This portion of text has been removed from this preview. 42-49 The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. Freeman, K., James, S., Klein, K., Mayo, D., & Montgomery, S. (2016). Outpatient Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for Adolescents Engaged in Deliberate Self-Harm: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33(2), 123-135. doi: 10.1007/s10560-015-0412-6 Guerreiro, D. F., Cruz, D., Frasquilho, D., Santos, J., Figueira, M. L., & Sampaio, D. (2013). Association Between Deliberate Self-Harm and Coping in Adolescents: A Critical Review of the Last 10 Years’ Literature. Archives Of Suicide Research, 17(2), 91-105. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.776439 Healey, J. (2014). Self-harm and young people. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com Hawton, K., Rodham, K., Evans, E., & Harriss, L. (2009). Adolescents Who Self Harm: A Comparison of Those Who Go to Hospital and Those Who Do Not. Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 14(1), 24-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2008.00485.x Hernan, A., Philpot, B., Edmonds, A., & Reddy, P. (2010). Healthy minds for country youth: Help-seeking for depression among rural adolescents. Australian Journal Of Rural Health, 18(3), 118-124. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2010.01136.x Name Here Project 2 15 James, A. C., Taylor, A., Winmill, L., & Alfoadari, K. (2008). A Preliminary Community Study of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) with Adolescent Females Demonstrating Persistent, Deliberate Self-Harm (DSH). Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 13(3), 148-152. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2007.00470.x Kõlves, K., Milner, A., McKay, K., & De Leo, D. (2012). Suicide in Rural and Remote Areas of Australia. Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention. Retrieved This portion of text has been removed from this preview. from: https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/471985/Suicide-inThe author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. Rural-and-Remote-Areas-of-Australia.pdf Low, G., Jones, D., Duggan, C., MacLeod, A., & Power, M. (2001). Dialectical behaviour therapy as a treatment for deliberate self-harm: Case studies from a high security psychiatric hospital population. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 8(4), 288-300. doi: 10.1002/cpp.287 Madge, N., Hawton, K., McMahon, E., Corcoran, P., Leo, D., Wilde, E., & … Arensman, E. (2011). Psychological characteristics, stressful life events and deliberate self-harm: findings from the Child & Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(10), 499-508. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0210-4 National Rural Health Alliance (NRHA) (2009). Suicide in Rural Australia. Retrieved from: http://ruralhealth.org.au/sites/default/files/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-14suicide%20in%20rural%20australia_0.pdf National Rural Health Alliance (NRHA) (2017). Mental Health in Rural and Remote Australia. Retrieved from: http://ruralhealth.org.au/sites/default/files/publications/nrha-mental-health-factsheet2017.pdf Name Here Project 2 16 Ougrin, D. (2012). Commentary: Self-harm in adolescents: the best predictor of death by suicide? – reflections on Hawton et al. (2012). Journal Of Child Psychology & Psychiarty, 53(12), 1220-1221. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02622.x Ougrin, D., Kyriakopoulos, M., Zundel, T., Banarsee, R., Stahl, D., & Taylor, E. (2012). Adolescents With Suicidal and Nonsuicidal Self-Harm: Clinical Characteristics and This portion of text has been removed from this preview. Response to Therapeutic Assessment. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 11-20. doi: The author has not authorised any further reproduction or communication of this material. 10.1037/a0025043 Rughani, J., Deane, F. P., & Wilson, C. J. (2011). Rural adolescents’ help-seeking intentions for emotional problems: The influence of perceived benefits and stoicism. Australian Journal Of Rural Health, 19(2), 64-69. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01185.x Scott, S., Diamond, G. S., & Levy, S. A. (2016) Attachment-Based Family Therapy for Suicidal Adolescents: A Case Study. Australian & New Zealand Journal Of Family Therapy, 37(2), 154-176. Doi: 10.1002/anzf.1149 Tormoen, A., Rossow, I., Larsson, B., & Mehlum, L. (2013). Nonsuicidal self-harm and suicide attempts in adolescents: differences in kind or degree? Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(9), 1447-1455. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0646-y