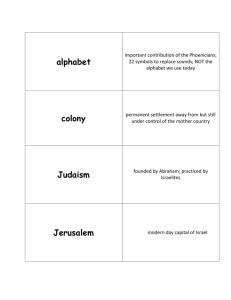

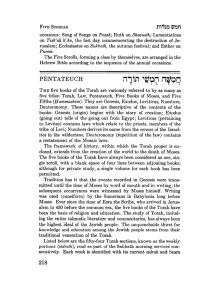

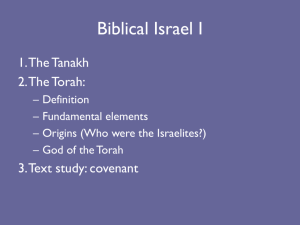

Torah: An Essay Having studied several intricacies of my ethnicity, my identity, (and to the extent of where I am in my spiritual journey), my religion called Judaism: it’s clear to me that, among all the dissent, arguments, assertions, scholarship, etc. there is universal agreement within and outside of the Jewish community: Everything begins with Torah. I asked these questions early on in my studies: Why Torah? Why not the Rig Vedas? Why not the Upanishads? Why not other philosophical, religious, mythical, or otherwise culturally relevant texts in the world? Surely, from our point of view: Each of these sacred texts in their own rite do not represent historical documents (and indeed, many of them date earlier than the Torah). Your answer to me: Because it’s our book. I simply do not, and cannot, and don’t believe in Torah’s messages. Stoning teenagers? Nope. Flood? A bullshit story (and we all know that). So, you, having gotten to know me – I wonder if part of you may have figured that such an answer isn’t going to be prima facie satisfactory and, perhaps you left it at that so that I could determine for myself whether or not Torah is My Book. After exhaustive thinking, reading, and – as much as I hate to admit it – feeling: Without question, Torah is My Book. I’ll finish this essay by explaining how I came to this personal certainty. First, I suspect that its important that I demonstrate at least a cursory understanding of Torah. I will also explain the Documentary Hypothesis. I don’t agree with some (or quite frankly, a lot) of JEDP, but it did serve as an effective framework and starting point for me to get a better understanding of well, The Torah and Me (which could easily be the title of this essay). The Torah The Torah, Pentateuch, first 5 books of the Tanakh – goes by many names. As I understand it, however, the word “Torah” can be effectively translated as “Instruction.” To summarize my understanding of its overall significance: The Torah’s stories, laws and poetry stand at the center of Jewish culture. From Creation of the world, to (as I like to call him) Father Abraham and Sarah in Canaan, to the exile and redemption from Egypt, to Israel, and the Hebrews’ subsequent travels through the desert until their return. Israel enters into a covenanted relationship with God, and in Deuteronomy, many of the societal and personal rules for governing and living a Jewish life. Onto the 5 books: Genesis/Bereishit (“In the Beginning”) o Genesis tells the story of creation, Noah and the flood, and the selection of Abraham and Sarah and their family as the bearers of God’s covenant. Stories of sibling conflict and the long narratives of Jacob and his favorite son Joseph conclude with the family dwelling in Egypt. Throughout the first account of creation, God is called Elohim. But starting in Genesis 2:4, a second and different account of creation begins - in which God is called Yahweh (more on that later) Exodus/Shemot (“Names”) o This begins with Jacob, his family, and the subsequent enslavement in Egypt. The Israelite figure of Moses emerges. I’m not sure about this, but as I read Exodus, it seems that he was initially “adopted” by Pharaoh, and of course becomes God’s prophet. Then we have the 10 plagues upon Egypt, and Charlton Heston (oops, I mean “Moses”) parts the Red Sea and leads the Israelites to Mt. Sinai. Here, Moses receives the 10 Commandments (and traditionally I believe, the entirety of Torah), only to come down from the mountain seeing his people worshipping the Golden Calf, which pisses him off. Or does it? Perhaps it’s in love, to spare the Israelites from knowing the consequences of God’s commandments. In any case: Moses subsequently destroys the commandments, however this leads to the building of the First Tabernacle. Leviticus//Vayikra (“And God Called”) o Now that we have the Tabernacle, Leviticus deals mostly with laws of Israelite sacrificial worship. More laws/rules follow such as Jewish dietary laws (kashrut/kosher) and issues of purity and impurity. It seems that an overall motif an emphasis on community. Diving into two major parts: 1) Largely about the individual sacrifices, 2) Holiness: Focuses more on what it means to create a holy society. Numbers/Bamidbar (“In the Wilderness”) o I understand that a “census” of the Israelites starts the book and the Levites (priestly class). It seems that a group of Israelites venture outside Canaan to spy. Why? Because they feel the need to build their Kingdom, and the spies came back with unfavorable reports. But because they distrust to God for their protection: God, (I guess) leads to the entire tribe wandering the desert for 40 years, during which the Israelites (once again!) behave badly, and rebel against Moses and his brother Aaron, and are promiscuous with local women (“Moabites,” I think). So, those 40 years were just enough time for the old generation of horny Israelites to die off, giving way to a new generation. Deuteronomy/Devarim (“Words”) o Deuteronomy is Moses’ final message to the people of Israel before they cross over the Jordan River into Israel. Moses reiterates the redemption from Egypt, and here is where we get the details of the covenant between Israel and God. The language is pretty black and white here: Everything is described in terms of Reward and Punishment. The “Documentary Hypothesis” It goes without saying that I’ve never believed that Torah contains any historical, factual information. There’s little question that Moses (or any of the other figures described in Torah) never existed, nor did any of the events happen. Of course, while millions of people believe that to be these stories true, and I don’t: I wanted to see what modern scholarship had to say about it. You introduced me to the JEDP concept which was quite helpful in showing that (of course) there were many authors that breakdown into 4 categories: The Yahwists (“J” from the “Jehova” form of the Tetragrammaton) -- ~ 950 B.C.E o As the name suggests, the Yahwists were characterized by using the Tetragrammaton (YHWH) as the name of God and, where this name is used: This serves as evidence of their distinct authorship of those parts of Torah. The Elohists (“E” owing to the use of “Elohim” for God) -- ~ 850 B.C.E o Again, Elohim is used by the Elohists rather than YHWH. The Priestly Source (“P”) -- ~ 600 – 500 B.C.E. o Interestingly, there is a 200-300 year gap between J and E. Contributions of “P” to Torah seem especially concerned with stories and laws relevant for, well, priests. I suspect that a lot of these writings may have either been “revisionist.” At least from my research: “E” and “J” don’t really codify monotheism, whereas “P” is where monotheism seems to be more clearly expressed and finally: The Deuteronomists (“D”) -- ~ 700 B.C.E. – written, and then updated o Presumably, these were the authors of Deuteronomy. Incidentally, I read that there may have been a single author of Deuteronomy, a man named Shaphan. I wasn’t able to determine whether or not this was an actual historical figure. In any case: “D” predates “P,” which is why I figured that, when the JEDP model was conceived in Germany in the late 1900s, it may have suggested that “P” was revisionist. What to make of this? Initially, I had figured that this was a widely-accepted theory of non-Orthodox Jewish scholarship but, in recent times: This has been hotly debated. And really: I can understand why. It strikes me as exactly what it says, a Hypothesis (which is an apt name). I mean, there’s no historical evidence for this. Furthermore: I couldn’t find anything to support the dates to which each of these groups of authors are attributed by the JEDP model. Nonetheless: It is a fine Hypothesis, as it helps explain the inherent contradictions, repetitions, differing literary styles and terminology in Torah. Moving on, there does (did?) seem to be a loose consensus that the Torah as closely as we have it today, came about under the reign of King Josiah, the sixteenth king of Judah (c. 640–609) who, according to the Tanakh, instituted major religious "Deuteronomic" reforms. Was Josiah a Historical Figure? I don't know. Frankly, I'm always skeptical when the Primary Source for history comes from the Tanakh but, as you told me: The Bible essentially transitions from Myth to History in 1 Kings, where the reign of Josiah is described. Tanakh, of course – is outside the scope of this essay. So I did start doing research on hard, archaeological evidence for all of this. (That could be another paper in and of itself), but one of the discoveries that was significant to me was the Merneptah Stele. It was written in Egyptian, and is dated to around 1,200 B.C.E. (ie, predating the Torah) From what I understand, it represents the first documented instance of the name Israel in the historical record, and the only record in Ancient Egypt. This was very significant to me, as I’ll explain below. And of course: I did read about over a dozen other archaeological finds in chronological order, leading to the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947. Final Thoughts At some point: I realized that I wasn’t PhD in Archaeology, Theology, Biblical History, Aramaic, Hebrew, or any of the other things that would truly, once and for all, answer all my questions about Torah and, that’s when I realized the significance of it. Clearly, whenever it was written, whomever wrote it (not mythical “Moses”) it contains different ideologies and theologies, and are not uniform pieces of literature. The Torah has grown over centuries and is the result of many voices, influences from Jewish History (Babylon, Hellenism, Syria, and all sorts of periods of Jewish history – influencing the historic authors, whomever they were). Furthermore, the concept of “Torah” seems much broader than the books themselves, and “Torah” can refer to all of Jewish learning, presumably traditional – but in my case: What the orthodox would consider “non-traditional” learning. That’s exactly what I’m doing now in general, and most Saturday mornings. Suddenly, it’s not as important to me as to who wrote the Torah, but why it was written. To me, part of the beauty and richness of the Torah is what it produced: The Mishnah, Oral Torah, of course, but also the many midrashim, exegeses, commentaries, debates and fundamentally: NO AGREEMENT. Those seem to be common themes throughout Jewish history (which resonate with me, in case it wasn’t obvious). Outside of Fundamentalist Orthodox: There is no consensus. Finally, throughout all the reading, research, study of history and archaeological revelations about which I learned, I did find a cohesive theme throughout all of this: The Israelites were a very real, ancient people. Thus, Torah (in every sense of the word) is extremely relevant to Judaism and my life as a Jew. To me: Torah as a historical or even theological document is complete bullshit. I’m okay with that. Even though I am Jewish by blood, I am more importantly a Jew by choice. The Torah is My Book.