Data Adequacy and China - The possibility of an adequacy decision adopted on China in accordance with the GDPR Article 45

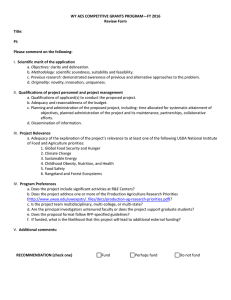

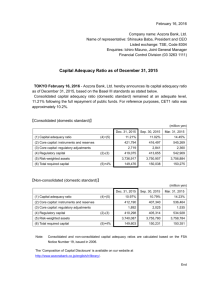

advertisement