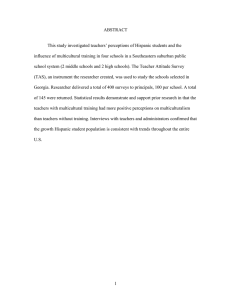

Thesis Sponsor: Dr. Cathy Benedict WHAT’S THE STEELPAN GOT DO TO WITH IT? AN ANALYSIS OF MULTICULTURAL MUSIC EDUCATION IN NEW YORK CITY SCHOOLS Nyasha Rhoden New York University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Music Education, Department of Music and Performing Arts Professions, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development December 2010 ii © Nyasha Rhoden All rights reserved December 2010 iii ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to examine the ways in which music of the African diaspora is addressed within a multicultural setting and how it informs the kind of engagements with students of the same background. Considering New York City is a main center for a multiethnic, social and economic population, it can be a model for multicultural education. Thus, this study examines the ways in which multicultural music is defined and implemented within the pedagogical constructs of New York City’s Blueprint for the Arts. Using this document as a framework, in addition to articles, statistical studies, and personal interviews, this study focuses around the absent historical, social, and political dialogue between students, teachers, and community. It further suggests the steelpan or steel drum as a pedagogical solution and vehicle to bridge the gap between multiculturalism in thought and reality. A steelpan curriculum can be an effective tool in answering multicultural education’s challenges, because of its historical, political and social qualities. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………….……………………………………………………………………..iv Introduction……………………….…………………………………………….…….…...1 Problem Statement……………………….………………………………………….…….5 Purpose of the Study……………...………….…………………………………………..12 Research Questions………………………………………………………………………13 Content Analysis of the Blueprint………………………………………………………..13 Blueprint’s Objectives…………………………...………………………………….…...16 Analysis of the Blueprint……………………………………………………….………..19 Multiculturalism within the Music Making Strand…………....………..……….24 Multiculturalism within the Wraparound………………….……...……………..25 First Inquiry…………………………………..…………….……………27 Second Inquiry………………………………………………….…..……30 Third Inquiry……………………..……..…………………..……………32 Rationale for a Steelpan Curriculum……………………………………………………..33 Cultural Connections…………………………………..…….…………….…….35 Historical Background and Spiritual Ties………………………………………..40 Socialization Tool……………………………………………….……………….48 Holistic Approach…………………………………………….………...………..51 Summation……………………………………………………………………………….52 Glossary………………………………………………………………………………….57 Reference List……………………………………………………………………………58 v vi Introduction I came to this study because there is a special connection between the city, my students and myself that I wanted to address. I am an African woman born and raised in Brooklyn, New York with African Caribbean parentage. Some of my personal friendships fostered in school were examples of the cultural diversity in the city. I currently work in a middle school setting and teach at the same school I attended. Many of my students and I have similar backgrounds. They are born in America with parents from African, Latin Caribbean or Asian backgrounds. Living in the same Brooklyn neighborhoods and attending the same schools contributes to me connecting with my students on a personal level. In many ways I see myself in and through my students. At an early age my mom enrolled me in various arts programs including those based on African culture. She taught me at an early age the importance of knowing my identity. I constantly sought out experiencing and understanding my culture in areas such as African dance and playing in a steelband orchestra. Not only did I personally connect to the historical attributes of the instrument, but also through its unique sound, which transcends words, it touched my soul. It reminded me of the hip-hop music that filled my portable cassette player as a child. Hip- hop had a similar story of acceptance by the middle and upper class in America. These struggles were so familiar to me that learning the craft of playing this instrument became infectious and inevitable in keeping with my African identity. It reminded me of all the music’s of African people that initially were called ‘jungle’, ‘primitive’, or ‘wild’ and once dialogue began became acceptable, innovative and praised. 1 My formal and informal music training was driven by self-determination to express myself. Not to mention the support from my family, friends, and teachers; who constantly encourage me to think outside any imaginary lines I draw for myself. Through this medium I am able to connect and re-connect with my family, steelpan community and ancestors. Through my formative years I was told sayings like, “to whom much is given, much is required”, “a tree without its roots is dead”, “you don’t know where you’re going until you know where you came from”. These proverbs and principles stay within me and remind me of the responsibility I have to give back to the community as well as the respect I desire to show to my elders and ancestors. Therefore playing the steelpan pays respect to my people and their culture. As a student I was unconsciously frustrated with the misrepresentation of the people of African descent contributions to society. Due to the lack of multicultural classes in school, I took outside courses addressing this deficiency. However, at one level of my development, I thought it was more important to teach European music in a steelpan class because I thought it would validate the instrument as a suitable unit of study. These ideas stemmed from my internal discord with my identity as well overarching societal pressures to fit in. I had conflicting ideas of acceptance and validity as a result of my attempt to submerse my students and myself into the mainstream/traditional music classroom setting. As an attempt to successfully assimilate into ‘white’ America, I was sacrificing the most important thing, me. At the same time I knew that students would benefit from a steelpan curriculum because of their personal connection to the culture. Many come from an African and Latino background. A multicultural music curriculum was important in my classroom but critical exploration around the repertoire was not my concern. I realized that my lack of 2 understanding the necessity to liberate my mind stifled the creative energy and potential of my students. At this point multiculturalism in practice was not present. Transformation from an unconscious to a conscious person is constantly developing over years of frustration, defiance, assimilation, awakening and attempts to critically analyze my own thoughts and actions. These engagements were part of the process of transforming my classroom and myself. As a teacher I began to look at ways in which these issues could be addressed in the classroom. I wondered if my students felt similar frustration with the educational system not providing sufficient material on African history and culture. I wondered if they wanted to learn more about their parents’ history and culture and how understanding these things would positively influence my student’s productivity. Observations of student’s interests and development in the classroom led me to address the lack of multiculturalism in my music curriculum. For example speaking to a child who had a reputation of erratic behavior and long visits to the deans’ office, I asked him what were the reasons he went from failing class to receiving the highest grade. His responses were that he was tired of doing poorly in school, and that he enjoyed playing the steelpan, and it made his parents proud the he was learning about the instrument of their birthplace. He wished that he had taken steelpan earlier in his schooling and wanted to be in the more advanced steelpan ensemble especially because he would be moving on to high school at the end of the year. The further developed steelpan group is given advanced music and performance opportunities. The student wanted to be a part of those experiences. His intrinsic motivation to improve was due to several factors. The student culturally saw a connection between himself and the music. Due to the students’ familial roots he was interested in the subject matter. He began to see advantages to playing an instrument. I could 3 see real contentment in his eyes when his father was surprised and proud when I told him his son was an exceptional player and he should study the art form further. The steelpan curriculum appealed to this child in a special way and represented fundamentally his uniqueness. Part of his identity was culturally represented in the curriculum and it created a feeling of existence and equal participation. I believed the young man saw himself in the music he learned and through his authentic experience he began realizing his self-worth. He challenged the false idea that children at the middle school age are only concerned about how they are perceived by others. He saw the need to improve and created higher goals and made strides towards attainment. But as many advancements as the student made, there was still critical multi-cultural concepts missing from the steelpan curriculum. Although a steelpan class could be considered multicultural repertoire, it is only through critical assessment with oneself as the teacher, critical analysis with the musical repertoire and critical engagements with students can true transformation occur. According to Bernard (2008), “In order to help to create and facilitate thoughtful and meaningful experiences with students through a multicultural lens, teachers should locate themselves in the everyday practices to see how their interactions can manifest, represent and transform the theories and philosophies they believe” (Bernard, 2008, p ). A curriculum’s content is dependent on a teacher’s experiences, thoughts and practices. Teachers should analyze their interactions within the world, within the curriculum and within the classroom in order to understand students. In order to understand what a multicultural lens looks like, teachers should examine the meaning of multicultural education and how it interacts with their own interests and actions. 4 Problem Statement When examining the rise, development and purpose of multicultural education, one must look at its origins. “Multicultural education” was founded on the Black civil rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s in the United States. Black folk seeking to improve their political, economic and cultural rights influenced other exploited groups such as Caucasian women, within the country and various parts of the world, to raise their voice against injustice. Marginalized groups “demanded that their histories, cultures, and languages be reflected in mainstream institutions and in the public and civic culture.” (Banks, 2009). Emerging from the frustration of being excluded from the planning of curriculum in the school system came this notion of ‘multicultural education’. According to Banks (2009), “Over four decades and through several phases of development, “multicultural education” evolved into a transformative idea whose implementation requires substantial changes in all of the major variables of the school so that students from diverse racial, ethnic, cultural, language, and religious groups experience educational equality” (p. 1). The complexity of ensuring representation in the school curriculum requires consistent reexamination including multiculturalism in music education. Elliott (1995) examines the coexistence of many different musical groups and ideals within a society, saying, “multicultural music education connotes a social idea: a policy of support for exchange among different groups of people to enrich all while respecting and preserving the integrity of each” (p. 14). The exchange of ideas begins with each human holding the ultimate power over their freedom regardless of race, gender or class. The 5 implications multiculturalism has on music education did not end with the rise of the civil rights movement. It is a continuous exchange among marginalized communities and the organizations designed to represent the educational curricula being taught. Conceptually, “multicultural education” seems unfailing, ethical and advantageous. However, its actions in American education and American music programs are often absent or superficial. Way too often, America’s music curriculum emphasizes music of Western origin. It deemphasizes any music art other than that of European background. For example, there are undergraduate music education programs that do not provide students with at least one core requirement in jazz history or improvisation. Although jazz is categorized as an American music, programs focus mainly on music of the traditional classical genre. In addition to completing the program students must learn jazz music on their own time in order to meet certain music program criteria demands in K through 12 schools. Jazz is just one example of the various musical genres practiced in American communities. One reason this may be is because some institutions having aspirations of achieving Western conservatory level rather than adequately providing an all-inclusive program to students, especially in cities heavily populated by people of African, Latino and Asian descent. Perhaps some institutions have interest in providing a multicultural program to students. Perhaps some institutions do not see the advantages to sustaining such diverse program, or do not know how to balance high levels of classical music instruction with multicultural programs, or have a challenging time seeking the resources, instructors, musicians, and artists within these particular communities to interact and work with. Nonetheless, the music’s of these people are missing from the discussion. And these are some of the same communities music educators work in after graduation. Children in 6 these communities are challenged to connect with educators who may not relate with students culturally, economically or have similar interests as students. Educators are given the challenging task of creating the environment for the equal exchange of music’s, cultures and ideas without adequate education about these groups represented in their own voices. There is a disparity between the concept of multicultural music education and its implementation in American music programs. Many higher education institutions including K through 12 continue to deflect their community’s cultural diversity. These imbalances in representation of exploited groups are not only found in education but in all aspects of society. Focusing solely on Western music’s in curriculum does not authentically represent the multicultural background that is the foundation of American society. Bernard (2008) posits, “In North America, music of English and Western origins is sometimes considered multicultural despite the fact that Western music’s are sonic demonstrations of people who share more cultural similarities than differences” (p. 2). Western music derives from the people’s of European descent experience and principles and can not encompass the experiences of other people’s in America. The challenge music educator’s have is exhibiting America’s cultural diversity in addition to addressing its social, cultural and political identity, concerning race, gender and class. Therefore, the problem is that communities as a whole, and especially those inhabited by marginalized groups, people of African descent in particular, are not equally represented in music curricula, in education as a whole, and in mainstream society. For this studies purpose we will only examine music education through a multicultural lense. 7 There are inconsistencies between the concept ‘multicultural education’ and its practice. Multiculturalism is represented as an idea without actual implementation. Multicultural music education must face the issue of marginalized communities not only being misrepresented in curricula but also excluded from the conversation, politically, economically and socially. If multicultural educational curriculum does not adequately address these issues, it is not multicultural. As a music educator, I have observed programs devoid of the African experience. Even when terms such as ‘multiculturalism’ are used, African peoples music’s, voices, and experiences have been missing or compartmentalized with other disparaged groups. Misrepresented groups are not given their own voice , their own identity, and therefore their own power in the conversation, nor are they able to collectively determine the aspects of education that are important to them. As communities take on different racial, cultural, and socioeconomic shapes, the schools’ curriculum should become tangible images of that community. Curriculum should not only mirror its environment but question its forms. Curriculum should at the same time embrace multiculturalism and question its form and essence. Examining language like ‘multicultural education’ or ‘global education’ can appear appealing to the educator yet are problematic. These terms can become confusing and create contradictory language. These words can potentially establish a mood or idea with which people can feel comfortable and affiliate with particular pedagogical practices. Multicultural education can connect with the instantaneous or emotional side of a human being but if not practically applied to the curriculum, it can become slogans. Rather, these terms can feel good to its users but not take actual forms. 8 Popkewitz (1980) maintains, “The potency of a slogan is that it can create the illusion that an institution is responding to its constituency, whereas the needs and interests actually served are other than those publicly expressed. The slogan may suggest reform while actually conserving existing practices” (p. 304). Conserving the existing practices that slogans carry, preserves the status quo, maintaining marginalized groups misrepresentation in mainstream curriculum. They have the power not only to connote an idea but take form in perpetuating the ‘culture of power’ Delpit (1995) sees present in classrooms (p. 24). The community may think the institution is representing various student groups’ interest, however changes do not actually occur. Even phrases can maintain a groups or class interests. In form and action the power is still in the hands of a small few. Through slogan building, institutionalizing non-mainstream culture in educational pedagogy are perhaps sympathized with but not enacted. The sustenance of these terms as slogans are not only found in education but in all areas of life. At root slogans are always political. Therefore if multicultural education does not seek to empower marginalized groups, it is not actually multicultural. If it does not seek to give voice to the voiceless and empower the powerless then it only maintains the constructs already put in place by the people in power, the elite class. Furthermore, calling a group ‘marginalized’, ‘misrepresented’ or ‘minority’ does not address the specific people’s interests. Rather it puts all people in one big group without allowing each the highest potential of power. There may be several groups interests at hand. Theses words can also hold ideas that keep groups within the particular label. Words like ‘minority’ can become slogans as well. Marginalized groups are defined by outward entities, rather than their inward identity. They are defined by other groups interest rather then their own interests. This language represents a certain class of people. Popkewitz suggests, “the 9 ambiguity of language serves a political function” (p. 304). Curriculum is the manifestation of the political milieu within a society. Therefore a multicultural music curriculum should seek to address the issues of mis- or non-representation and the political power of marginalized groups within a cultural context. In regards to the political power multiculturalism can yield, Sleeter (1996) observes a schools conceptualized idea of multicultural education as having little connection with community-based organizations that aim toward equality and social justice (p. 240). When the intelligentsia talk about multiculturalism without practical engagements, multicultural education takes the form of academic discourse (Platt, 1993). Within this framing, multiculturalism is only an idea, a code word for anything non-Caucasian, yet failing to lead to social reform and action. To solve this problem, Sleeter proposes multicultural education as a social movement. The social movement metaphor suggests a very different change process - one in which parents and other concerned community people, as well as educators, organize to pressure schools to serve their interests and those of their children (p. 242). The type of conversations and interactions occurring amongst students, parents, educators and community determine the level of pressure placed on schools. If the entire group or collective is not aware and in agreement with the need for change, then dialogue will not occur. In order for multicultural education to become a social movement, the collective would have to agree that schools are not providing students with sufficient information that will benefit their interest. They would have to examine these conditions and have to agree to at minimum level what aspects of the curriculum they agree or disagree with, and create a plan to change the conditions. Multicultural education as a social movement can yield a certain amount of political pressure. 10 History has shown countless records of how organized people can reform society or radically change society. Multicultural education has the ability to politicize the interest of disenfranchised people, particularly parents of and children of color and/or of low income backgrounds; children who are disabled, gay or lesbian, and their parents or adult supporters; and girls (p. 242). Social movements can not only politicize girls interest but women who are exploited, discriminated against, and objectified. Movements can make us aware of the issues. Social movements can lead to collective action. However, social movements focus on problems and conditions and can not change the root cause of problems. Social movements are just that, social. These types of organizations do not encompass all aspects of life. They focus on the social issues of society. Because within a social organization can be found various ideologies, they are not designed to articulate at root the ideologies that frame the issues People face. Although multicultural education as a social movement can yield political pressure, it can not yield political power which is all encompassing. Politics covers every aspect of life. Culture is political and therefore, pedagogy and its institutions are political as well. Multicultural education as a social movement can occur in microcosms but can not permanently change all of society. It may politicize our conditions but does not have the ability to radically change society and its systems. Nonetheless, multicultural education as a social movement is crucial to educational reform. It can combat the surface issues of education. It can reform education. It can make us aware of the conditions that marginalized groups face. Multicultural education can create the space for a conscious school climate. In this vein, multicultural music education can frame reformed music pedagogy, a conscious music classroom, and help to awaken all participants to lack of representation of marginalized groups in music pedagogy. 11 Purpose of the Study Therefore the purpose of this study is to examine The New York City Department of Education’s (NYCDOE) Blueprint for the Arts (2008) as a foundation of analysis. New York City teachers of the arts have been advised to use the Blueprint for the Arts (2008) as a guide to strategically planning music curriculum as a “result of an exceptional collaboration between educators from the school system and representatives from the arts and cultural community of New York City” (pg.3). Examining this description, the Blueprint seeks to represent the diverse cultures present in an urban setting such as New York City. And therefore seeks to represent marginalized groups of the community. It seeks to create a multicultural environment for the music classroom. Looking through the eyes of my own identity and experience, I plan to examine the form and function of the suggested repertoire, ensembles, and lesson plans that represent marginalized groups of African heritage in the NYCDOE Blueprint for the Arts (2008) in addition to its implications. An examination of the current definitions of multiculturalism throughout the text, including other supported materials, will frame a rationale, representing a broader voice missing from the Blueprint. I will investigate specifically the African Caribbean themes and experiences found throughout the Blueprint and create a rationale for a steelpan curriculum. Although this investigation cannot satisfy and address all the issues, it can serve as a framework and basis for deeper discussion concerning multicultural themes in music pedagogy in particular and education in general. 12 Research Questions The following research questions guided my study: 1. How is multiculturalism being addressed in the New York City Arts curriculum? 2. How could broader definitions of multiculturalism frame a steelpan curriculum? 3. In what ways can a steelpan curriculum address multiculturalism in arts program? The Content Analysis of the Blueprint The New York City Arts curriculum is based on the Blueprint for Teaching and Learning (Blueprint). New York City arts teachers receive several professional development courses based on the Blueprint every year. Teachers are encouraged to implement the document in addition to providing feedback that is considered for future editions and workshops of the Blueprint. In this study, the five different sets of content strands or standards of the Blueprint for Teaching and Learning in Music were analyzed in relation to the philosophical educational culture within which they play a role. A strand is considered an “essential aspect of teaching and learning in the arts”. These fundamental phases are emphasized throughout every aspect of the Blueprint. The strands are intended to frame the music teachers strategic planning throughout the school year, and “spur the individual creativity, depth, and breadth in music teaching” (Blueprint, p.14). 13 Within each strand is a component categorized by core (also known as general music), vocal, and instrumental music, a unit plan stating long and short term body of related lessons, listing goals, outcomes, materials, broad procedures and assessments. The strands are found throughout every aspect of the Blueprint and each unit plan is geared towards the mastery of the standards. These strands include: I. Music Making II. Music Literacy III. Making Connections IV. Community and Cultural Resources V. Lifelong Learners The theoretical framework for this study is based on a content analysis of the musical strands at the completion of the middle school grade level. This type of examination was used in this study to compare and contrast the strands, within the context of multicultural education. Content analysis provides a systematic procedure for describing content, identifies clear examples, themes and patterns in the data, and supports the qualitative side of the study by quantifying the appearance of categories, words, or phrases. However, this type of analysis cannot be qualitatively sufficient if the data is not interpreted through my knowledge and interests. It is more important that I clearly articulate the themes of multiculturalism found in the Blueprint rather than the reader finding one true meaning or content of communication through the writer. The writings of Delpit and Freire shape this study. These authors were used to provide a framework around the themes and hidden meanings found in each strand and the 14 masked structures within education and society. Delpits’ work focuses on the misdiagnosing and misinterpretation of communication of ‘children of color’ in the educational system and the necessity for teachers to understand the process of learning in the educational system and in society. Freires’ work was chosen because this study postulates the status of multiculturalism in music education as a product of the dominating political fundamental beliefs in the world and the Blueprint for Teaching and Learning in Music is a byproduct of this thinking. Both writers’ work focuses on issues similar to the ways in which the Blueprint addresses multiculturalism, and is the manifestation of the society’s conscious or unconscious political, social, and cultural relationships. This study suggests that the Blueprint in all areas is evidence of an ideology. And is the perpetual representation of the dominant ideology. The Blueprint’s articulate approach to teaching and learning music is vast in all aspects. Each strand is deserving of a thoughtful and thorough critical analysis and each grade level (benchmark). Due to the constraints of this study, I will only be able to focus in depth on Strand One, Music Making. However, this study is not based on preserving the established constructs prescribed for music teachers by each strand, or grade level. It is not confined to the idea of just making music. Rather, this study focuses on multicultural educations’ form and practical application; authentic and critical. Making music intertwines with all the four other strands. Based on the music making process, the four strands can simultaneously interact creating the foundation for critical engagements with students of all ages. 15 The Blueprint’s Objectives Review of the introduction to the Blueprint, provides a clear aim for all New York City public school arts programs to utilize the city’s community resources and the unique cultural circumstances in order to provide every child with an exceptional arts education. The specific circumstances of New York City include its diverse cultural population and the types of interactions between social divisions. The Blueprint is suggested as a roadmap to direct teachers towards specific goals and outcomes through relationships between parents, community, and cultural organizations. Active engagements and interactions between arts specialists (music teachers, artists in residence), parents, and cultural organizations occur when all the city’s resources are maximized. It suggests that the plan has the potential to transform or evolve provided the clear and rigorous forms of assessment based practices offered in the field (Blueprint, 2008, p. 9). In theory, the Blueprint can aid in an effective multicultural music program. The Blueprint’s approach to collaboration is based on both subject-based curricula, which define the goals for the content taught and outcome based curricula, which defines the goals for the learner. Teachers are encouraged to select the approaches that work best for them and their students. With this suggestion in mind, what is most critical to the success of both objectives is the student-teacher relationship and students’ input. The character of student-teacher relationships can contain a fundamentally narrative character or a critical engagement approach. The latter requires teachers not to impose their own thoughts on students but rather seek ‘authenticity’ of students thinking. It is only through a students’ true 16 thinking that a teachers thinking is authenticated. It is concerned about reality and can only occur in communication (Freire, 1970, p. ). A successful arts program is dependent on the school and communities shared values and commitment to collaboration in providing the space for uninhibited creative energy to flow. However, the former is of a narrative character and suffers from a lack of boundless creativity. Students are a means to an end, objects of consumption and must be filled like containers by the teacher. These objects are subjugated to what Freire calls the ‘banking’ concept of education, in which the scope of action allowed to the students extends only as far as receiving, filing and storing the deposits. This writer’s critical analysis of the “teacher – student relationship at any level, inside or outside the school reveals the fundamentally narrative character” (p. 71). The narrative process contains words “emptied of their concreteness and become hollow, alienated, and alienating verbosity” where students are shaped into mechanical objects and containers of information. They lack human inquiry and expression. Students are dehumanized in this process, constantly moving away from reality. Teachers are the narrators ‘filling’ the students minds into ‘good citizens’ believing the better their mind ‘filled’, the better the student. Framing students’ thinking is part of the culture of education. The critical analysis approach does not prescribe answers to students and teachers but rather creates the space for students to develop their “unique personal voice and experience the power of music to communicate (Blueprint, 2008, p. 10). Humanization occurs in the critical analysis approach. Students are considered individuals with particular thoughts and interests. Rather, dehumanization, which marks not only those whose humanity has been stolen, but also (though in a different way) those who have stolen it, is a distortion of the 17 vocation of becoming more fully human (Freire, 1970, p. 44). Critical pedagogy seeks to counteract, or rather counter attack the dehumanization process by socializing students and therefore socializing teachers. Consequently, through further inquiry of the goals of the music Blueprint: “A Roadmap to Strategic Planning”, should include a student-based curriculum, which defines the goals for the content and skills students seek to learn. Also called student centered learning, this curriculum is based on students’ needs, interests abilities and learning styles. This teaching method focuses on the student requiring them to take responsibility, actively engage in their learning, and take ownership of their development. Student-based curriculum in conjunction with critical pedagogy stimulates all participants thinking. As students internalize the material being taught, they can decide on what information matters to them and why. They can determine what information they need. When disenfranchised groups are given opportunity to consistently engage in learning, the gap between multiculturalism in practice and theory constantly minimizes. Therefore, this study will examine the Blueprint’s objectives in the context of multiculturalism and how these goals frame its practical application in the music classroom for students of African origin. The study will analyze the Blueprint's narrative and critical characteristics throughout the suggested repertoire, lesson plans, and objectives and how its practical applications can direct students of marginalized groups (of African descent in particular) and teachers to achieve more critical engagements with each other and the community. This study will analyze whether the Blueprint can frame the socializing aspect of multicultural education. This study will examine whether this document shapes multicultural education as a social movement. 18 Analysis of the Blueprint The Blueprint (2008) is structured to a child’s particular grade level called a benchmark. A benchmark indicates the level of a students’ achievement from the 2nd grade, 5th grade, 8th grade and 12th grade. Found in each level there are five strands, I. Music Making, II. Music Literacy, III. Making Connections, IV. Community and Cultural Resources V. Careers and Lifelong Learning. The first strand explores the act of creating music physically. Music Making – “By exploring, creating, replicating and observing music, students build their technical and expressive skills, develop their artistry and a unique personal voice in music…They understand music as an universal language an a legacy of expression in every culture” (p.10) Words like ‘exploring’, ‘creating’, ‘replicating’ and ‘observing’ are operative terms, implying all participants are putting music into action. However, there is more to music than only making music. All words imply a thought before an action. Among these terms, ‘replicating’ can suggest certain ideas to the teacher and student. It can imply a student’s 19 unique interpretation of information framed and modeled by the teacher, or it can instruct students to follow, repeat back, and regurgitate information. Unless explicit information is given, the latter poses a problem to the teacher or student who wants to be aware of the content presented because it gives the sense of assimilation. Replicating can be problematic to the independent thinker, independent teacher or the independent student, because it suggests submission to certain structures present. Delpit (1995) proposes that dominant ideology is present in the practical examples of the “culture of power”. The type of culture is determined by the codes or rules present in the participation of power. She suggests that in the classroom there are issues over the power of the teacher over the students; the power of the publishers of textbooks and of the developers of the curriculum to determine the view of the world presented (p.24). Depending on the educators’ own awareness, understanding, and examination of the culture of power, her students’ will become explicit or implicit participants of that culture. An educator may teach directly from the textbook without critically analyzing the books content. A teacher may make an unconscious decision to instruct students to replicate by repetition. She may not fully understand the culture of power and the role she plays in it. She may seek ‘multiculturalism’ in the classroom but not know how to unleash these types of engagements. Not cognizant of the dominating culture of power can lead students to regurgitate information rather than create the “environment that affirms their fledging self identity and developmental capacities” (Blueprint, 2008, p.12). In addition the teacher may be wary in addressing her student’s race and its political ramifications in society. These structures of power are not only confined to the classroom setting. 20 There is a culture of power present in all spheres of life. Everyone partakes in the culture of power and consumes a culture through education. Ideology is a way of thinking. Culture is the container of ideology and ideology is a class’s all encompassing system of fundamental political beliefs. The dominating class determine the rules, principles, practices and pedagogy that all people make conscious or unconscious choices to adhere to. Delpit (1995) explains, “the rules of the culture of power are a reflection of the rules of the culture of those who have the power”(p. 24 ). One may be unconscious but still uphold the dominant powers principles. People unaware of the rules of the culture of power will fall prey to its consumption. Unconscious people maintain and sustain the dominant culture in society. In this form, replicating information will lead to one’s voice becoming inferior, or becoming silenced, while another’s dominates. The multicultural music curriculum cannot manifest in an implicit environment. Delpit (1993) finds this silenced dialogue as a suppressed agreement with the elite classes logic (p. 39). Multicultural pedagogy is the antithesis of a silenced dialogue. For example, she recounts a tape by John Gumperz on cultural dissonance in cross-cultural interactions (p. 26). It showed an East Indian being interviewed for a job with an all white committee. The interview went steadily downhill as the several ‘helpful’ interviewers became more and more indirect in their questioning. The interviewers and interviewee were coming from different cultural perspectives, which ultimately resulted in the interviews failure. Delpit determines that as the applicant showed less and less aptitude for handling the interview, the power differential became more and more evident to the interviewers. The “helpful” interviewers, unwilling to acknowledge themselves as having power over the applicant, became more and more uncomfortable. Their indirectness was an 21 attempt to lessen the power differential and their discomfort by lessening the power revealing explicitness of their questions and comments. (p.27). The more the interviewers didn’t acknowledge the applicants cultural difference and the more indirect the questioning, the more cultural dissonance occurred. Whether the interviewers indirectness was intentional or not cannot be determined but what is clear was the presence of the culture of power over the applicant. Perhaps his cultural difference was unrecognizable to the interviewers. Nonetheless, not acknowledging the applicants cultural differences, denied his cultural presence. Denying one’s existence continues to preserve the power disparities present. Whether understood by all participants or not, a silenced dialogue leads to one group being the oppressed and the other, the oppressor. In turn, a silenced dialogue can occur in the classroom as well. The teacher can become the oppressor and her students oppressed, unconsciously maintaining the rules of the culture of power. “Even with well intentioned educators, not only our children’s legacies but out children themselves can become invisible. Many teachers we educate, and indeed their teacher educators, believe that to acknowledge a child’s color is to insult him or her” (Delpit, 1992, p. 245). If a teacher does not acknowledge and address her similarities but more crucial her cultural differences, then there is not only a denial of the student’s cultural presence but their existence within the culture of the classroom. Delpit (1993) concludes that members of any culture transmit information implicitly to co-members (p. ). Curriculum can also transmit information to students. Students can also transmit information back to teachers. Implicitly, students can maintain the status quo without even realizing it and never question the teacher’s intent through the curriculum and the importance of it to them. Friere (1970) explains the submersion in the reality of oppression prompts one to become assimilated. And 22 Comment [1]: Nyasha Rhoden Oct 15, '10, 10:39 PM find page in Delpit through this delusional attempt of adhering to the rules and logic, one attempts to become the oppressor, or sub oppressor (p. 65). Through assimilation, the oppressed become agents of their own oppression. Deyhle and Swisher (1997) define assimilation as adopting “the white man’s language, values, skills, knowledge, customs, attitudes, and religion. Formal education seeks to institutionalize the assimilation process” (p. 113). “While the structure has changed somewhat, this practice has changed very little in the past 100 years” (p. 115). The assimilatory model keeps educators framing curriculum around assimilationist goals. These structures of power are not only confined to the educational system. McCalman (2003) views the process of assimilation through migrant workers whom, as they gain economic stability, blend into the norms of popular culture of the host country (p. 42). The more the migrant worker blends into the status quo, the more the migrant worker becomes less of himself and more of the oppressor. Assimilation can lead to the oppressed becoming an agent of their own oppression. Furthermore, a dialectical relationship exists between society’s culture and our classroom culture. There is a relationship between mainstream society’s consciousness, the classroom consciousness, and the educator and student’s consciousness. Our identity is shaped by and reflects our consciousness. “Culture is therefore the manifestation of life in society and it expresses at the same time the fundamental bases, the rules on which are founded different societies whose creative activities direct towards certain values” (Nkrumah, 1964). Curriculum’s consciousness is based around these principles, interests, and guidelines. Implicitly or not teachers are part of the sphere of holding one consciousness superior over others. Teachers are not devoid of mainstream society’s culture and 23 consciousness. The Blueprint is a manifestation of the codes of power in pedagogy. Examining the ways the Blueprint situates itself in the dynamics of music curriculum and multiculturalism, frames the mainstreams culture and consciousness. Multiculturalism Within The Music Making Strand The first strand in all grades (2nd Grade, 5th Grade, 8th Grade and 12th Grade) of Music Making informs students of the continuity in mastering basic engagement, understanding and integration of the elements of music through performance (p. 18, p. 30, p. 42, p. 54). Within the second benchmark called 5th grade, self-awareness, self expression as musicians through performance, improvisation, and composition is the level of most significance due to its high need and risk in an authentic multicultural setting (p. 30). Teachers and students become cognitive of their place in the world and recognize themselves not as objects of narratives but as humans, and the means and the ends. All participants see themselves as conscious beings whom bring an important role to the whole, to the classroom, and to the world. In reality, self-awareness directs self-analysis. Within this understanding one can find the problem-posing method. Freire (1970) states, “Students as they are increasingly posed with problems relating to themselves in the world and with the world, will feel increasingly challenged and obliged to respond to that challenge. In problem posing education, people develop their power to perceive critically the way they exist in the world with this and in which they find themselves; they come to see the world not as a static reality but as a reality in process, in transformation” (p. 83). 24 Teachers are also a part of the problem posing dialogue, “constantly reforming his reflections in the reflection of the student” (p. 80). Constant transformation and reflection occur and in turn the classroom is constantly being re-created by student and teacher. “Problem posing education involves a constant unveiling of reality” (Freire, 1970, p. 81). Multiculturalism education remains in a constant state of transformation where the awakened person is mobilized and acknowledged as “historical beings” (Freire, 1970, p.84). Practically, multicultural music education is to develop conscious, critically engaged persons with whom through dialogue, problem-posing theory and practice, begin transforming themselves, in turn, transform society. Problem-posing in theory and practice develops students and teachers understanding of the power of consciousness and self identity. Multiculturalism within the Wraparound The Blueprint (2008) determines middle school students have an exhilarating range of characteristics and contradictions. They are develop the following skills and understandings at the Grade 8 Benchmark: 1. Physical/Social: Students acquire vocal and instrumental dexterity: discover leadership skills; and engage in increased peer interaction and group decisionmaking. 2. Cognitive: Students analyze, differentiate, create, and compare performances, repertoire, and experiences 3. Aesthetic: Students develop self-expression as music makers; integrate music learning with observations and choices 25 4. Metacognitive: Students consider and assimilate a range of musical experiences to make appropriate responses (p. 12). A middle school level multicultural music curriculum would encompass all of the above skills, being mindful of, and perhaps not using words like ‘assimilation’ because of the potency that it creates. Assimilation means just that, to assimilate into something else. Popkewitz (1980) considers, “these common phrases give identity to curriculum” (p. 304). Curriculum contains not only an identity but also a consciousness. Whether implicit or explicit, our classroom is a result of our society’s conscience. Therefore, we educators consciously or unconsciously participate in the potency of slogans. However, authentic multiculturalism’ of music pedagogy in form and action is the conscious critical analysis of slogans in curriculum and within us. Authentic multiculturalism requires one to be in a state of alertness, combats the potency of slogans and allows learners to make conscious decisions. For example, the Blueprint (2008) introduces the concept of a ‘Wraparound’ as a “creative and organized tool for teaching repertoire through the five strands of learning (p. 15). The Wraparound is a tool for lesson planning and can be translated with greater detail into Units and Lesson Plans. The first song suggested in the 5th grade ‘Wraparound’ is “Yonder Come Day” based on the traditional Georgia Sea Islands spiritual and arranged by Judith Cook Tucker (p. 39). This study will examine this piece because of its cultural representation and characteristics of Africans in America. It suggests three questions for teachers to answer through the repertoire. 26 First Inquiry: 1. What do students need to know and be able to do in order to authentically and successfully perform the musical selection? This question speaks to the Music Making strand, which deals with the act of performing a musical piece and the cultural context within which authentic processes occur. In addition, it poses teachers and students find genuine interactions with the suggested piece of music. Other questions that should be posed in this section are : • Why do students need to know this musical selection? • What is the function of this music in society? Authentic examples should entail explanations through interactions with musicians from the Georgia Sea Island area in conjunction with forms of media that create more understanding of the people and their culture being performed by them. “Yonder Come Day” can be an effective tool for teaching music in a ‘multicultural’ framework provided understanding the historical, political and social conditions surrounding the repertoire. David Pleasant, a multi-faceted musician and native to the Gullah/Geechee (Georgia/South Carolina) Sea Islands discussed this popular arrangement of “Yonder Come Day” with me. He believed although the arrangement adequate in its own right missed key characteristics regarding the percussive qualities and rhythmic nuances of its traditional form in addition to its cultural framework. He recalled his own experiences with Gullah/Geechee elders who reminded him to “let his feet sing like the song do.” Unique harmonic characteristics, foot stomping, tambourine clapping, drum playing, are some of the physical 27 attributes lost in translation in addition to the aesthetic qualities that are not understood by foreign interpreters. In other words, “Yonder Come Day’s” interpreted version lacked the authenticity the Blueprint recommends teachers to understand and capture in performance. The underlying theme is multicultural music is supposed to bridge the gap between the music and the people’s cultural, social and political experiences around making that music. Multicultural music is only actually multicultural when equated with experiences with the people of that culture. According to Freire (1970) authentic multiculturalism takes the form of analyzed dialogue. The essence of dialogue is the word and within the word we find two dimensions: reflection and action (p. 87). One does not exist without the other. Multiculturalism in its true sense is ‘authentic’ opposed to a false form of multiculturalism, which is unauthentic. Freire’s study found the following: An unauthentic word, one that is unable to transform reality, results when dichotomy is imposed upon its constitutive elements. When a word is deprived of its dimension of action, reflection automatically suffers as well; and the word is changed into idle chatter, into verbalism, into an alienated and alienating ‘blah’. It becomes an empty word, one that cannot denounce the world, for denunciation is impossible without a commitment to transform, and there is no transformation without action. (p. 87). Additionally, the Blueprint accounts for this relationship between words in action and reflection in the description of the “Qualities of Music Learning Experiences” with the following: Music Making: A complete music-making experience includes opportunities for: • Hands-on and interactive learning • Self Expression • Reflection 28 The Blueprint does not describe action other than direct interaction with the music. However, within the framework of reflection are action and the possibility for music teacher’s to create authentic engagements with students of diverse backgrounds. It is up to the teacher, the arts specialist and the school administrators to put the Blueprint’s ideas into action. Action can be understood several ways. Extensive analysis of the infinite possibilities provided in action of reflection, or the reflection in action creates authentic critical engagements. Critical engagements not only occur in the classroom setting but within people’s interactions with society and the world. Freire (1970) suggests this as ‘authentic reflection’ as neither abstract man nor the world without people, but people in their relations with the world. Woman/man is not abstract, isolated, independent, and unattached to the world (p. 81). Rather woman/man resides in the world and the world within woman/man. Each having an ethical responsibility to the other, and relying on the other. Reality resides in people’s engagements with each other and thinking that occurs within these engagements. In the same way the teacher who is committed to her students is ‘truly concerned about reality’ will need to make conscious decisions regarding the manifestation of authentic multiculturalism in the classroom, she will need to criticize her own engagements with and within the world and her students within the world. The teacher will have to understand her student’s reality. Through these interactions and processes, an authentic musical and nonmusical teaching and learning environment may begin to emerge (Bernard, 2009, p.30). Fundamentally, the music making process transcends the act of making music and can address problems found in music pedagogy through deeper or higher analysis. 29 Many times teachers are fixated on the notion that a successful curriculum is based on the quantity of repertoire an ensemble knows and the types of music performed. I have fallen prey to this type of ideology, wanting to teach my students Classical music, sometimes called ‘high’ art as ‘true’ engagements with ‘the most’ complex music, perhaps I thought it to be the most important music to teach. As I reflect on this thinking, I saw it as a part of my conditioning as a classical flutist. At the time, I did not understand and appreciate the diversity and complexity in the music of the African Diaspora. I have heard music teachers of African descent speak on Classical music as a type of ‘high’ art or perhaps the best genre of music. At this level of music instruction, the condition of the classroom is in constant flux with the cultural conflicts within the teachers’ and students’ identity, creating false engagements with students and the music. Therefore, authentic multiculturalism focuses on thinking, the quality of the music, examining all aspects of the people who created the genre, with respect to the peoples’ definitions of their music, and critically engaging all participants in music, smashing the constructs that maintain the disenfranchisement of indigenous groups. Second Inquiry: 2. What tools and resources are uniquely available in New York City? This inquiry encourages New York City educators of various school settings to find support and useful material among the organizations and people of the community. It can be coupled with the Blueprint’s (2008) fourth strand, Community and Cultural Resources, which is described as, 30 “Students broaden their perspective by working with professional artists and arts organizations that represent diverse cultural and personal approaches to music, and by seeing performances of widely varied music styles and genres. Active partnerships that combine school and local community resources with the full range of New York City’s music and cultural institutions create a fertile ground for students’ music learning and creativity” (p. 10). Building community relationships requires critical engagements with school, parents and community. The Wraparound of “Yonder Come Day” prescribes participants to find and listen to folk music of their own and other peoples’ culture, create harmonies with these songs, in addition to visiting the Black History museum (Blueprint, 2008, p.39). Seeking out community and cultural resources aids in understanding the authenticity of music through its people. It encourages teachers to investigate their own culture as well as their students through community support and organization. In addition, the Blueprint attached a community organization directory called the, “Arts and Cultural Education Services Guide”. This guide is designed to provide New York City schools with access to educational programs of New York City’s arts and cultural community. It contains a description of arts organizations and its contact information. Periodically the booklet is updated to attempt to meet the constant development of arts and cultural services. There are a few programs advancing the understanding and practice of African culture through the arts, in addition to some promoting African Caribbean culture more specifically. Moreover, this idea of working with professional artists can promote the Blueprint’s fifth strand called, “Careers and Lifelong Learning”. It is defined as, “Students consider the range of music and music related profession as they think about their goals and aspirations and understand how the various professions support and connect with each other. They carry physical, social, and cognitive skills learned in music, and an ability to appreciate and enjoy participating in music throughout their lives” (p. 10). 31 By developing relationships with artists and organizations, students can see various music careers at work. When given hands on interaction with professionals, ones goals and aspirations become more tangible. Students tend to be engaged in the multicultural process with further interest and motivation. Third Inquiry: 3. What are the most effective ways to engage students in the process? One answer to this question is found within the Blueprint’s definition of the third strand called Making Connections, “By investigating historical, social, and cultural contexts, and by exploring common themes and principles connecting music with other disciplines students enrich their creative work and understand the significance of music in the evolution of human thought and expression” (Blueprint, 2008, p. 10). The assessment for this strand asks students to describe ways in which “Yonder Come Day” is emblematic of Gullah culture and its people (p. 39). It promotes ideas of multiculturalism by asking participants to understand and articulate the characteristics of the specific culture, however, further analysis should ensue. Additional discussion might entail students comparing and contrasting the historical background of Gullah people with the historical, social, and political settings of their own. Multicultural education should aid participants in inserting themselves within the context of the music. Probing for engagements within music’s themes and principles compliments the Blueprint’s recommendations to create that “fertile ground for students’ music learning and creativity” (p. 10). There is a dialectical relationship between all strands. Perhaps examining each strand singularly only scratches the surface of what authentic 32 multiculturalism looks like in the classroom. The more teachers can interconnect all five essential aspects of teaching and learning in the arts, the more students are engaged within the process, and the more effective multiculturalism occurs. Moreover, the Blueprint also has a section called, “Stocking the Music Classroom” which states the physical requirements and inventory for an instrumental, choral and core music studio. Conventional music programs are recommended such as strings, winds and percussion. However, non-Western instrumental groups are not present. If the Blueprint’s recommendations will enable each school or campus to create an environment in which the delivery of music instruction can be offered at the highest level possible” (p. 64), then multicultural music classrooms can be implemented for students of all grade levels and cultural backgrounds. Rationale for a Steelpan Curriculum To this effect there is room for a steelpan curriculum to be included into the New York City Blueprint for the Arts. The diverse cultural makeup of urban populations, such as New York City, encourages the implementation of multicultural music programs. The Caribbean population in New York City alone speaks to the need for a steelpan curriculum in the school. Because the steelpan originates from the Caribbean, one can examine the quantitative measures of New York City’s population of people from the islands, which alone demands for a multicultural curriculum to be implemented into the school system, particularly a steelpan curriculum. 33 According to Kent (2007), between the 17th and 18th century U.S. laws allowed whites only to enter the country. Among the few blacks whom did arrive, most were of African heritage and born in the Caribbean. The Blacks immigrating to the United States in the early 1900s primarily settled in New York and few other cities. Jamaicans and other West Indians created ethnic communities; an estimated one-quarter of the black population of Harlem in the 1920s was West Indian. The term West Indian refers to African immigrants born in the Western Hemisphere, also called Afro-Caribbean, these people are from English speaking Caribbean countries, along with their children (Kent, 2007, p. 5). The early 1970s brought on new developments that resurged immigration from the Caribbean and Africa. New laws, cheaper and more frequent air travel, better communication means through telephone and email connected immigrants to their families back home and sent news of job opportunities to potential immigrants. Better economic opportunities, and a more politically hungry and conscious black population were powerful “push” factors. Between 2000 and 2006 the U.S. black population contributed to one-fifth the growth in United States immigration. In New York City more than a quarter of the black population is foreign born, including other major urban hubs like Boston, and Miami. The term foreign born refers to any U.S. resident who was born outside the United States or its territories, except for people who were born abroad to parents who were U.S. citizens (p.5). More specifically, results from the 2000 Newest New Yorker found approximately 88,794 people born in Trinidad and Tobago residing in New York City, preceded by larger foreign-born population groups from Jamaica, Guyana, and Haiti (p.7). Statistical reports are not always accurate when quantitatively measuring populations. Some still argue that Caribbean people are not counted enough in national polls such as the U.S. Census. However, these numbers 34 can guarantee that diversity has become a hallmark of the city’s foreign-born population (p.7). The patterns of diversity in New York City populations render a diverse curriculum in New York City public schools. A steelpan curriculum can be at the forefront of developing a multicultural music program in New York City. Therefore, the Blueprint has the capacity of developing a steelpan curriculum due to the following main elements: Cultural Connections The steelpan confirms cultural ties between people of Africa and Trinidad and Tobago, the people of New York City, and therefore to people all around the world. New York City’s cultural climate creates sustainable resources for steelpan music programs in school. For example, presently the New York City West Indian Day Parade and Carnival, brings at least 3 million participants and tourists to Crown Heights, Brooklyn, New York every summer. Held on the same day as the American Labor Day holiday, Carnival originally began in Harlem during the Renaissance era, throughout the late 1920s to early 1930s. According to Allen (1999), The early Harlem parade, was, by Trinidadian standards, relatively conventional. As an invite only affair, the parade was attended by masquerade bands and community organizations and guests. Allen’s interview with Caldera Carabello (1996) recalls the event as “a restricted parade, not really a Carnival.” He further states, “Carnival officials were concerned that steelbands might disrupt the otherwise orderly event”. Nonetheless, by the late 1950s, “steelbands were tolerated by the organizers because they wanted to showcase authentic Trinidadian culture, and pan had become a central component of the Carnival celebration back home in Port of Spain” (p. 257). Worries about 35 disruptive behavior became a reality during the 1961 Harlem parade. A fight broke out between panman and parade partygoer. In the end ten people were arrested for disorderly conduct. This occurrence coupled with a rock-throwing incident, led to the revocation of the Lenox Avenue parade permit. As one of the Harlem parade organizers, Rufus Gorin moved to Brooklyn, so did the Carnival celebrations. By 1971, approximately six steelbands, some small (twenty to thirty players) and some large (sixty to seventy-five players) turned out for the Eastern Parkway Carnival ‘parade’ (p. 257). Presently, the steelband community is an integral part of the Labor Day festivities, with at least ten large orchestras participating in the steel pan competition called Panorama on the Saturday night before Labor Day Carnival. Examining the steelpan’s value from the perspectives of people of identical or similar backgrounds, Morin (1989) believes a contemporary issue in North American education is cultural pluralism. Cultural Pluralism occurs when smaller groups within the larger society maintain their unique cultural identity, values and practices. However, assuming smaller groups are defined by identity such as religion and not by population, cultural pluralism is not possible when larger groups are exploited and marginalized by a small few. Certain practices in culture will clash if one group capitalizes on the other. Banks (2004) defines multicultural education as a popular term used by educators to describe education for pluralism. He believes pluralism’s goals are to reduce prejudice and discrimination against oppressed groups, to work toward equal opportunity and social justice for all groups, and to effect an equitable distribution of power among members of the different cultural groups. Schools that are reformed around principles of pluralism and equality would then contribute to broader social reform (p.66). However, schools with reformed educational practices can be effective for a small population but do not speak to the 36 institutionalized pedagogy found systematically in education. Authentic multiculturalism occurs when the masses of people seek to further understand themselves and how they affect the world. It cannot occur unless implemented throughout every aspect of education. Pluralism is not confined to a particular school population or urban setting or suburban area. Pluralism or multicultural education extensively studied leads to a necessity for examination of power constructs present in society. Delpit (1993) raises this issue of multiculturalism in the context of language diversity and power present in society and the importance of it being addressed in the classroom. She refers to a conversation between a black teacher and a black high school student named Joey. Joey’s consciousness was raised by thinking about codes of language. Students begin to understand how arbitrary language standards are, but also how politically charged they are. They compare various pieces written in different styles, discuss the impact of different styles on the message by making translation and back translations across styles and discuss the history, apparent purpose, and contextual appropriateness of each of the technical writing rules presented by their teacher. And they practice writing different forms to different audiences based on rules appropriate for each audience. Such a program not only teaches standard linguistic forms but also explores aspects of power as exhibited through linguistic forms (p. 44). Although Delpit speaks on language and writing styles one can substitute these words with music literacy and see the similar constructs present in multicultural music education. It would be to the effect of, Joey’s consciousness was raised by thinking about codes of musical language. Students begin to understand how arbitrary music’s technical standards are, but also how politically charged they are. They compare various musical pieces composed in different styles, discuss the impact of different music styles on the message by making translation and back translations across styles and discuss the history, apparent purpose and contextual appropriateness of each of the technical rules presented by the teacher. And they 37 practice playing different forms to different audiences based on rules appropriate for each audience. Such a program not only teaches standard musical forms but also explores aspects of power exhibited through musical forms. Authentic multiculturalism occurs when students begin to understand the codes of language present in making music and in the codes of language in society. The achievement of multiculturalism goals implies initiation into various cultural forms so that students may come to appreciate each unique musical logic, grammar, and syntax (Morin, p.12). Because the steelband is unlike Western music ensembles, one may become interested in playing it for its unfamiliar yet worthwhile value. The author continues to propose that an elementary school steelband program contributes to the multi-ethnic music education of students (p.12). Students who encounter and acquire multicultural education have higher appreciation, understanding, respect, and tolerance for non-Western music. Music making is not the only activity present in a steelpan curriculum. Being the only instrument invented in the 20th century, it provides a platform for further research regarding its scientific properties, new innovations, and the challenges that arise with a ‘young’ musical device. In addition, the steelpan’s unique voice or rather language is found interesting by Tanner (2007) who notices people, particularly Westerners find intrinsic value in the performance of Caribbean music. He furthers explains, “The rhythmic language of many Caribbean styles differ from our own, and that difference alone is worth exploring and experiencing” (p. x, preface). Tanner sees the steelpan’s characteristics as different to his culture and that alone warrants interest. He finds value in understanding an unfamiliar art form. McCalman (2003) also supports this idea, stating, “the notion that the steel band would only be of interest to 38 African Caribbean children is now gone for good. For educators the main issue is recognizing and valuing this specific knowledge and identifying the numerous benefits that children can derive from it” (p. 44). The steel band contains a universal language and therefore universal advantages. Nonetheless, one cannot veil the benefits a steelpan program can offer an African child. There are lifelong rewards in valuing one’s own culture and history. Britzman (1992) supports this view stating, “The problem of curriculum is the problem of identity. Our first struggles as teachers is to understand the fears, desires and commitments toward social life that our students hold and to create the conditions for students to become aware and concerned with what their own views about social life mean in the work of understanding self and others and in the forming of thoughtful social relationships” (p. 253). An example of cultural comradery can be found in Walrond’s (2007) observation of several female pan players while visiting a panyard. She states, “While their cultural heritages are as varied as Nigeria, Canada, Trinidad, and Ghana, they all have close ties to the steelpan. Some think that this is so because it is so similar to the drums. There were special codes” (p.31). The cultural ties crossed more than the countries these young women grew up. Most of them seemed to be coming from African backgrounds and this perhaps is what culturally connected them to the sound of the drum and perhaps created those special codes. 39 Historical Background and Spiritual Qualities The steelpan embodies a distinctive historical background that parallels its unique visual, tonal, and spiritual qualities. Within the evolution of steelpan lies a pivotal historical and political background and establishes the foundation for its unique development. As European nations colonized the Africa and the Americas, land natives became sick and died at large proportions. To appease this situation, over the span of approximately 3 centuries, millions of Africans were forcibly brought over and enslaved to toil the land for its resources and large economic gain. Slavery was not born of racism: rather racism was the consequence of slavery. Unfree labor in the New World was brown, white, black and yellow; Catholic, Protestant and pagan (Williams, 1944, p. 7). Trinidad and Tobago is one of many islands where Africans were brought and exploited as workers to toil the land. Then came capitalism, under which the greatest wealth in the society was produced not in agriculture but by machines – in factories and in mines (Rodney, 1970, p. 7). Seeking cultural output for the political, economical, and social unrest they faced, Africans utilized cultural forms of communication to creatively express their pain, anger, joy, and hope. Stuempfle (1995) shares a similar perspective prescribing the study of the steelpan and its history as a cultural phenomenon, with culture conceived of as a temporal and flexible system of symbols which is enacted and manifested in practices (p.4). These practices paralleled the historical development of Trinidad and Tobago. He expands, The panmen’s transformation of objects from their environment into musical instruments is one representation of the whole creative process by which Trinidadians have defined themselves as a people. In fact, the emergence of the steelband and its development up to the present parallel the emergence and development of Trinidad and Tobago itself as a nation. To a large extent, nation building has involved negotiations between Trinidad-Tobago’s various ethnic groups and socioeconomic 40 classes; and patterns of conflict and consensus in these negotiations have, at the same time, been played out in the dramas of the steelband movement. Similarly, the problems and successes of nation building are paralleled by a sense of struggle and achievement among panmen. Parallels such as these suggest that pan embodies some of the essential contours of the Trinidadian experience and can be interpreted as one of the central symbols of the nation (p.1). The steelpan development progressively transcends class structures and race issues that characterized mainstream society. Coincidentally, the struggle for steelband’s acceptance into carnival events in New York partially parallels the development of the steelband movement in Trinidad and Tobago. For example, from personal account, in New York City in preparation for Carnival season, people of various economic and social backgrounds can be found in steelband orchestras working for the set goal to win the Panorama competition. Presently, one can find young children, to ex-convicts, to lawyers, to East Indians, and Africans working collectively with high levels of commitment and involvement in a steelband. The steelpan’s unifying principles cannot only be traced back to its social features but its cultural and religious history as well. Kenrick P. Thomas (1999) identifies the steelpans unifying traits and overall development to its African origins more specifically to a district in Trinidad and Tobago called Tacarigua. During the early decades of the early twentieth century, when sugar production was a pillar of Trinidad and Tobagonian economy, most villagers depended solely on enterprises like Orange Grove Sugar Estates, Ltd. for their livelihood. Therefore, most of the villagers were of similar economic status. And although religious festivals and occasions were basically Indian oriented, the entire village looked forward to them, and actually participated. For, even though no efforts were made towards any form of superficial racial integration, racial intolerance was non-existent or, at most, extremely minimal in Tacarigua. 41 Not only was it common to see people of African descent attending the Mosques, weddings, and special observances, but African men in the district also excelled on the tassa drums which were played at the Indian weddings and hosay festivals, playing alongside their Indian fellow villagers (p. 3, 4). Experienced steelpan scholars date back the origins of steelpan’s evolution or development to the colonial government’s banning of the drum and celebratory activities associated with drumming to around 1883. The Peace Preservation Ordinance prevented all African traditions and practices restricted to reduce the resurgence of violence that intensified during Carnival season. Steumpfle (1995) notes that, during the 1870s public uproar concerning the degeneration of Carnival intensified also due to the fact that ‘obscene’ songs and masques, by then traditional to Carnival were performed with even greater gusto by the jamettes (p. 22). Essentially there was a push to remove or rather “improve” Carnival by the upper class. But the ordinance did not quell all activity of drumming and African culture throughout the country. Thomas (1999) surmounts that around this time Africans who practiced the Orisha religion (Shango), of African religious practices, settled throughout the entire Tacarigua district. In fact, Tacarigua was one of those districts in which Africans from the Yoruba tribe (called “Yarouba” in Trinidad and Tobago) who had been reduced to slavery were able to maintain and practice their traditional religion, albeit in an underground manner (p.3). Yoruban religious traditions can be traced backed to the people of West Africa before the Islam and Christianity. Curtis (1989) describes African tribes people incorporating musical rhythms into drumming and the use of the ‘atumpan’ or talking drums to acclaim the chief and announce important events (p. 25). Interestingly enough the word ‘pan’ can be 42 found in this African word ‘atumpan’ for talking drum that has developed into the steelpan or ‘pan’ in Trinidad and Tobago. Although publicly banned, Orisha drummers continued to permeate Trinidad and Tobago culture through other forms of percussion. Steumpfle (1995) also agrees with this observation adding that restrictions on drumming encouraged development of new forms of percussion for Carnival (p. ). New percussive developments came in the form of hallowed out bamboo sticks thumped on the ground at various lengths. Bamboo grew abundantly in Trinidad and Tobago therefore becoming easy adaptations of drums. Thomas (1999) identifies, the three-instrument arrangement found in Tamboo Bamboo Bands derived from the Orisha drummers “triad formation”. The Orisha drum ensembles consisted of three drums. The bembeh was the biggest or mother drum the midsize drum was the congo, and the smallest of the three, the umbillay. Each drum had a different tone, and when played together, they provided a rhythmic harmonized sound that was really pulsating, creating wild frenzy. Similarly, the tamboo bamboo band substituted the bembeh with the boom, the congo with the cutter, and the umbillay the fuller of foulé (p. 18). Wherever Africans peoples are, their artistic ingenuity is found. Throughout the world, several examples can prove that when African music was prohibited and suppressed, Africans found ways to create and recreate. Some may think it may be a result of attempting to recapture the music of Africa or by sheer accident. However, Green (1987) supports none of the aforementioned. She concludes the history of the steel pan having rudimentary beginnings in retention of African percussions (p. 93). Green supports the holding onto African tradition of the Tamboo Bamboo, precursor of the steel band, with the example of 43 the Ga speaking people of Ghana using bamboo tubes that are striked against a stone slab in the Ga-Adowa, the “Aho” section, the singing portion of festivities. The author continues, In examining the premise that the steelpan innovators in Trinidad were perhaps trying to recreate melodic instruments previously played in Africa, we find, for example, in the xylophones of the Chopi people, a close and startling resemblance. These xylophones use tin cans as resonators. The cans are cut and burned to temper the metal; then each is placed under a strip of wood of the instrument. THe can are graduated with the lower keys having larger cans. The Chopi xylophones are played in ensembles of soprano, alto, tenor, bass, and double bass much like the steel [pan orchestra] (p. 93). In addition, ancestral links to the retention of African music tradition can be found in Steumpfle’s (1995) reference to the people of Ghana, Venezuela, Haiti and Jamaica deploying similar bamboo instruments stamped on the ground. For example, after the seizing and destroying of drums in Haiti the bamboo bands of gambos became popular among the people (p. 23). Hill (1972) also states, “the dormant musical instinct of the African was awakened by the desire to quench those rhythmic urges, and the memory of the bamboo bands which were prevalent in West Africa and Haiti came to the fore” (p. 46). Hill argues that this awakening can be equated to, unlike the Indians and the Chinese, even under indenture, still had some direct bond with their ‘motherland’, the Africans losing their language and basic culture had no choice but to settle for Trinidad and Tobago as their homeland (p. 44). Therefore it would be efficient to understand Thomas’ (1999) argument that most of the creators of the steelband had direct links with the Orisha movement, primarily as outstanding drummers. Furthermore, the African Orisha drum was the catalyst or motor that really spawned the steelband (p. 26). The African Orisha or Yoruban practices can be found predominantly 44 throughout different tribes in West Africa. These views contradict some scholars’ perspectives stating that development of the steelpan came from a multicultural, or a crosscontinental background and that the grappling with the banning of the drum was marked a dilemma to the Africans. Thomas (1999) sees the line of continuity between the traditions of the old ‘homeland’ (Africa) and the cultural life in the new (p.26). Therefore, the steelpans primary underlying principles of unity and togetherness stems from the cultural container it developed within. Although spontaneous at first, steelpans evolutionary culture has a direct connection to the Africans struggle for identity in a ‘new’ land. Morin (1989) agrees with the aforementioned notion suggesting the primary principles of a steelband curriculum as containing unity, participation and togetherness (p. 13). Ironically, the underlying principle of unity contained in steelpan’s history finds mixed reception by some cultural bodies in Trinidad and Tobago. Regarding the expressed views of Trinbagonians claiming the steelpan as the national instrument of Trinidad and Tobago. Nathaniel (2006) examines the government’s advances in declaring the instrument a national art form. She surmises that there are mixed feelings regarding the Trinidad and Tobago government’s efforts to boost the steelband artform in the years following the announcement that it was the official national instrument of the country. Although there have been measured progress, it would appear that citizens have been looking for more significant government thrusts toward giving the steelpan more solid and formal grounding in society by way of organization and education (p. 125). Nathaniel’s analysis raises the concept of identification, representation and nationalization for the people of Trinidad and Tobago, more specifically the two majorities, people of African descent and people of East Indian descent. Looking at the logic behind the 45 opinions of Trinbagonians on opposite sides of the national argument spectrum, the concept of an instrument bringing people together or separating them can be clearer understood in an organizational and educational manner. Addressed in the music classroom, these concepts are teachable moments for all to explore concepts such as identity, nationality and whether a people’s government should recognize an instrument. Organizations can provide effective resources in aiding a classrooms understanding of culture and provide the political framework guiding that culture. For example, one could explore the steelpan’s different titles under names such as steel drum, steel band or pan and the reasons behind the naming and renaming of it and whether the naming of a thing has a particular background and impact on the people understanding and using it. Further study could lead students to question how they define themselves and whether their definitions fit within the mainstream society’s definition. On the other hand, there was a phase where the authorities constant harassment of players and the competitive nature from which the art form derived created serious rivalries amongst bands, which sometimes became violent. However, formation of steelband organizations, economic opportunities abroad and the scientific evolution of the instrument were necessary maturations of the steelpan movement. “Although they identify with the social struggle of the panman, most steelband musicians with whom I have talked remember the early days of the steelband movement as a time of exciting musical discoveries and innovations” (Dudley, 2002, p. 17). These factors prompted comradery and unity amongst bands that communities like Tacarigua exhibited from the steelpan’s early developmental period with the formation of the Tacarigua Welfare and Improvement Council, established in May 1945, which was at the forefront of community development in Trinidad and Tobago 46 (Thomas, 1999, p. 5). During Trinidad and Tobago’s post independence era, post 1962, and during rise of Black Power protest, during the early 1970s, the Steelband Improvement Committee gained support of an increasing number of bands and became the official steelband association under the name of “Pan Trinbago” (Stuempfle, 1995, p. 156). Steelband, like other educational activities requiring bonds among participants, (parents and school staff) contributes to the cohesive force that gives school membership its community spirit (Morin, p. 14). Steelpan programs transcend certain characteristics that are not practiced in other ensemble settings. Steelpan musicians are encouraged to move and dance while playing. Especially during the Panorama competition, some bands encourage their musicians to ‘entertain’ the audience with choreographed movements. Although some steelpan musicians see the need to focus more on the musical arrangements rather than the choreography, Tanner (2007) recommends that steel band personnel interact with audiences in the manner of other popular music ensembles; such interaction is quite distinct from the typical separation between performers and audience members in an art music context (p.xi). The size and mobility of the various steelpan instruments requires players to work collectively especially when carrying and setting up instruments. teaching songs aurally. Players must Unlike other settings where players are only responsible for their own particular instrument and music, the steelpan encourages players to help each other. Parents and school staff can also get involved in the organizing efforts of a program from transportation to organizing logictics to acquiring potential performance venues which encourage school participation, school spirit and parent involvement. 47 Socialization Tool The steelband is a major socializing agent (Morin, 1989, p. 14). The instruments unique sound and interesting qualities can attract even the hardest criminal. As previously stated and from personal account ex-convicts can be found in steelband orchestras working positively and progressively with blue-collar folk. In a school setting students with discipline challenges can benefit from participating in a steelpan group. Historically, the steelband movement has been a disciplinary training ground for troubled Trinbagonian youths. Morin points out that the irony of fifty ‘unemployed and undisciplined’ pan players mastering the European classics like their literary counterparts, is indicative of an unexpected sustainment of energy (p. 14). Labeled ‘unproductive’ and ‘unruly’ also called ‘bajans’ meaning ‘bad Johns’, the steelpan youth were some of the first to organize and employ groups of steelpan players, mainly young men of African descent. Lawson (1991) examines the impact the formation and implementation of a steelpan ensemble had on at-risk students at several pubic schools in a district in Florida. Majority of the students were from low socio-economic status and of African and Hispanic heritage. Although they did not comprise of the majority of schools’ population they represented the majority of at-risk students. The purpose of the organization and implementation of the steel drum ensemble was to solve the problem of low academic achievement, high discipline incidents and isolationism amongst these students. Participants studied and rehearsed music of their background such as Caribbean, Salsa, Latin, African and American (p.4). Results determined a 60 percent increase in students’ cultural knowledge, in addition to ninety percent of students achieving academic success and 90 percent not receiving disciplinary 48 infractions (p.34). The evidence suggests when students were provided with a music curriculum focused on styles and customs of Africa, the Caribbean, Creole, and Latino cultures, not only did knowledge of their own familial cultures increase, but knowledge of cultures other than their own increased as well (p. 5, 31). The use of a multi-cultural curriculum and critical thinking had positive effects on the students. Within Lawson’s research he determined there being no texts or references on steel drum performance techniques (p. 23). However, since the publishing of his work, in the 1990s, there has been a gradual increase of reading resources providing strategies to start and build a steelpan program. Nonetheless, written materials directly targeting effective steelpan ensemble rehearsal techniques and methods is of small quantity and difficult to locate. Lawson’s solution included allowing participants to identify main issues in effectively playing the notes on their respective instrument and creating an action plan to learn the multicultural repertoire. Although the author states his personal experience of being a music educator for several years and his knowledge of teaching at all levels, one questions at what level is his own steelpan experience and how did his experiences inform the critical engagements he had with students. What is not clear is the methodology used by the author. One cannot determine what specific solutions to the problem of learning to play were rendered. According to Lawson, “The author assisted the target group by encouraging free expression of ideas and not judging participant’s solution strategies. The author assisted the target group in encouraging orderly deductive reasoning in tallying the ensemble’s consensus of opinions” (p. 25). This study is an effective example of student-based learning. Challenges, goals and methods were determined by the students to create. 49 In addition, although the parents of the at risk students, administration and community resources were utilized, one cannot determine if among them were steelpan players or someone with steelpan knowledge. In this regard, one can understand the need for students to identify the problems in learning how to play the steelpan and pinpointing techniques that worked unless all participants including the teacher had no prior experience. It appears everyone was a new learner to the process. Nonetheless, the author saw a necessity for a multicultural music curriculum. He states, “In the practicum site school district there was a documented need for multicultural education. The non existence of any multi-cultural music education curriculum was an immediate concern” (p. 20). “A feeling of isolationism and non cohesiveness was statistically evidenced by many minority drop-out rates, poor academic achievement and poor discipline problems” (p. 18). Lawson saw the lack of multiculturalism as the main reason Black and Latino students were isolated and misunderstood the cultural cohesiveness found in schools is directly influenced by the implementation of multi-cultural educational curricula and faculty awareness training. Holistic Approach 3. Has the capacity to render a holistic approach to the musical experience. Morin (1989) found that a steelpan program can support natural modes of music making as educationally desirable (p. 14). Validation of this idea is found in Lawson’s examination, which included participants brainstorming ways to learn the notes on each of the respective instruments. In Harris’s article “Expanding the Role of the Steel Drum Band”, he recalls his experience with classically trained students who were apprehensive to improvise and afraid of playing incorrect notes. A steel band classroom fosters student’s exploration and develops their improvisational skills (p.2). 50 Nachmanovitch (1990) deems all art as improvisation. And improvisation is the most natural widespread form of music making. Some improvisations are presented as is, whole and at once; others are doctored improvisations that have been revised and restructured over a period of time before the public gets to enjoy the work. Up until the last century, it was integral even to the literate musical tradition in the West (p. 6). This writer sees art from the West and the rest of the world as naturally improvised bodies of work. Steelpan is an effective vehicle to transmit all aspects of music. Although the art form derives from an aural tradition, there are growing opportunities for steelpan composers to utilize written traditions and write music for various sized steelpan ensembles. More steelpan repertoire is becoming available to the public through institutions, workshops and websites around the world. Concerning steelpan’s repertoire, Tanner (2007) finds numerous opportunities for improvisation. The steelpan advances general musicianship, improvisation, free play, sight-reading and high levels of creativity. Playing the steelpan is easy to learn but difficult to master. Elementary music educators are constantly searching for types of activities that are simple enough for children to participate in successfully and offer simultaneously a genuine musical experience (Morin, 1989, p. 14). The steelpan allows these types of activities to occur. Currently, the earlydeveloped steelpans called ‘ping pong’ are gaining interest in American elementary schools because of its amiability and light maneuverability. Some steelpan manufacturers are beginning to mass produce these instruments for major instrument retailers. In addition, Tanner (2007) recognizes that “there are no awkward fingerings to negotiate, no breathing control issues, no embouchures to learn and surmises almost anyone can have a baseline level of success playing the steel band, and thus the ensemble provides a valuable resource for a music program that desires to reach out to as many as possible” (p. xi). 51 Music educators can incorporate the natural traits of steelpan playing infused with more advanced approaches, depending on grade level. Personal experience with steelpan artists and creators has taught me the high levels of theoretical perception that the steel band has the capacity to teach students, such as the circle of 5th, tonal scales, and the patterns of notes found throughout all the steelpans. These patterns represent the natural order of notes in most steelpan instruments. Educators can challenge their students’ technical ability, theoretical knowledge, and aesthetic experience through a steelpan curriculum. A multicultural education can aid in students overall academic achievement. Summation There is a personal connection to the familial, historical, and political attributes of the steelpan art form for the author. It reminded her of the hip-hop music that filled my portable cassette player as a child. Hip- hop has a similar story of acceptance by the middle and upper class in America. These struggles were so familiar to the author that learning the craft of playing this instrument became infectious and inevitable in keeping with her African identity. It reminded her of all the music’s of African people that initially were called ‘jungle’, ‘primitive’, or ‘wild’ and once dialogue began becoming acceptable, innovative and ironically ultimately praised. Presently some African art forms are ‘product pushers’ influencing the mainstream to buy. Although, one hopes that African art forms will stay organic, focused, and authentic forms of expression of the masses of people rather than profiting a small few, it is suffice to see that the steelpan has a story that must be told in the American school system. 52 Unless educators are intrinsically interested in the steelpan or have a familiar connection, one may find it difficult to seek out organizations, musicians and steelpan makers who can help in learning how to play, and starting and maintaining a steelband. Nonetheless, steelband curriculums are making progress. Several organizations, schools, colleges, and universities such as the University of the West Indies, Northern Illinois University, Florida Memorial College, and the University of Akron posses music degrees with steelpan concentration. Nevertheless, mostly small groups within the African people’s population utilize the steelpan to educate the community. The steelpan can still be considered “a secret” within America populations of people of color. Many may not know or understand the benefits of a steelpan curriculum. One must see the need for schools to utilize the artform to help children, especially those of the “atrisk” population. “Educators cannot teach what they themselves do not understand. Schools of higher education must make a multicultural music curriculum a part of the training of teachers to prepare them to deal with the Black aesthetic experience along with other cultural experiences” (Curtis, 1988 p. 26). Educators must be trained and sensitive to the Black experience they will face in the classroom. Especially if the educators are of a different background to students, they must be equipped to dialogue with students on cultural, social and political levels. Curtis’s statement holds true approximately twenty years later. If institutions of higher education do not deal with the Black or African experience, within these three levels, they are maintaining the multicultural There is a systematic problem in the lack or low number of multi-cultural music programs within music institutions in America. A multi-cultural educators purpose is to understand students interest and the cultural, social, and political constructs that frame their 53 understanding of the material. Therefore all music programs in higher education should include multi-cultural music programs. Multi-cultural programs have the ability to speak to the community’s needs and interests. Schmidt concludes, the linear and elitist face of the music curriculum continues to impart westernized concepts and ideologies (p.3). Although the elitist are of a small population, their music, culture, interests, and practices continue to dominate music pedagogy. All of these practices are based on ideology. An elitist ideology says it is acceptable to keep another’s music, culture, interests, and practices and ideology suppressed especially if it gets in the way of the dominant groups interests. Schmidt infers that this is based on the respect for expert knowledge and the obliteration of cultural and social constructs” (Schmidt, 2005, p. 3). However, one must further inquire on what this respect for expert knowledge Schmidt speaks on means because ‘what experts’ or rather ‘which experts’ is the question. An expert in anything can be a novice in something else. An expert may think they know all but may only hold fractional knowledge. More reverence should be given to experts who come from the same particular background of the subject being researched. It is in this same experience the expert lives. Moreover, if this latter observation holds true, the aforementioned researchers findings support the observation that some institutions remain seriously deficient in training pre-service teachers in different styles of music, despite a plethora of rhetoric and some progress in practice (Wang and Humphreys, 2009, p. 29). Wang and Humphreys reinforces the idea of multicultural education as maintenance of slogans and ‘feel good’ curriculum. Students, who are trained to become teachers without provided with adequate and authentic multicultural education, are not equipped to teach the 54 whole child. Unconsciously pre-service teachers are reinforcing elitists interests and maintain their ideology. Institutions should not use terms like ‘melting pot’, ‘globalism’ or ‘ethnic and yet maintain the mainstream practices of multiculturalism at the same time. Slogans contain contradictory language and lack action. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to propose a steelpan curriculum as part of New York City’s Blueprint for the Arts. This new curriculum is just one example of America’s educational system representing the various peoples of the nation. It is through examining, questioning and altering frameworks such as the Blueprint that we can begin the dialogue of how multiculturalism will look and feel like within the educational system. A theoretical analysis of current multicultural themes was addressed. Examining the multicultural themes found within the Blueprint exhibits space for an articulate multicultural program. The framework of the document contains several key components and inquiries that compliment a multicultural program. This analysis contains specified forms of multiculturalism in the form of a rationale for a steelpan curriculum. Further research renders the creation of a steelpan curriculum to be included in the Blueprint and put into action. Further information to assist educators with starting a steelband and building a steelpan curriculum is contained in the references. It is hoped that the ideas presented to readers will serve as a generative source for thought, discussion, and active engagements with students using a steelpan module. Institutions of higher learning, community based organizations, and open minded educators, parents, and students will be key components in developing this module and becoming active 55 participants of building authentic multicultural music programs not only in New York City, or nationwide but worldwide. 56 Glossary Ga-Adowa: A traditional dance performed by women and played as funeral music by the Ga people of Ghana. Jamette: A female jamette was part of the lower class sector, also considered the bad girls of the group part of the least educated and poorest, but supported the men of the steelband. Steelpan: A percussive melodic instrument made of steel. Originally made of oil drums, the steel is heated and cut to various lengths with the top sunk in and shaped into circular tones of atleast two octaves chromatically in the key of C. Steelband/ Steel band: A group or ensemble of several different types steelpans, also called the steel orchestra. It consists of instruments called the tenor/lead pan, double tenor/double lead pan, double seconds, triple guitar/cello, double guitar, quadrophonics, tenor bass, and six/nine bass. Variations to the steelpan orchestra can be found throughout the world but have basic sections of high, middle and low pitched steelpan instruments. Trinbagonians: A short way to describe people of Trinidad and Tobago citizenship. Panorama: A music festival held during the Carnival season where steelpan orchestras are required to play technically advanced arrangements of calypso/soca songs of the season by memory. The competition is native to Trinidad and Tobago but has become popular in several countries and often held around their Carnival season as well. Pan yard: The place or area where steel bands rehearse. 57 REFERENCE LIST Allen, R. (1999). J’ouvert in Brooklyn Carnival: Revitalizing Steel Pan and Ole mass Traditions. Western Folklore, 38(3/4), 255-277. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1500461 Banks, J. A. (Eds.). (2009). The Routledge International Companion to Multicultural Education. New York, NY: Routledge. Banks, J. A. (1997). Educating Citizens in a Multicultural Society. New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University. Banks, J. A., Banks, C. A. M. (Eds.). (2004). Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives (5th ed.). York, PA: John Wiley & Sons. Bernard, C. (2008). Thinking, reflecting, and articulating: A teacher’s engagements with musical and extra-musical experiences through a multicultural lens a phenomenological study (Unpublished master’s thesis). Westminster Choir College, Rider University, NJ. Blueprint for the Teaching and Learning in Music, Grades PreK-12. (2008). Retrieved from the New York City Department of Education website: http://schools.nyc.gov Britzman, D. P. (1992). Structures of feeling in curriculum and teaching. Theory into Practice, 31(3), 252-258. doi: 10.1080/00405849209543550 Curtis, M. V. (1988). Understanding the Black Aesthetic Experience. Music Educators Journal, 75(2), 21-26. Delpit, L.D. (1992). Education in a multicultural society: Our future’s greatest challenge. Journal of Negro Education, 61(3), 237-249. Delpit. L.D. (1995). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. New York: New Press. Deyhle, D. & Swicher, K. (1997). Chapter 3: Research in american indian and alaska native education: From assimilation to self-determination. Review of Research in Education, 22, 113-194. doi: 10.3102/0091732X022001113 Dudley, S. (2002). The steelband “own tune”: Nationalism, festivity, and musical strategies in trinidad’s panorama competition. Black Music Research Journal, 22(1), 13-36. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1519963 58 Elliott, D.J. (1995). Music matters: A new philosophy of music education. New York: Oxford University Press. Fairfield’s County Children’s Choir (2008, May 11). Yonder come day [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mJU4ayBCjCs&feature=related Friere, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum Publishing Corporation. Green, D. (1987). “The Steel Band as Universal Black Art.” Pan Magazine 1987: p. 93-94. Print. Harris, S (2002). Expanding the Role of the Steel Drum Band: It’s not just another Percussion Ensemble. Retrieved from www.tsmp.org/band/percussion/pdf/Steel%20Drum%20Band.pdf Hill, E. (1972). The Trinidad Carnival: mandate for a National Theatre. Austin: University of Texas Press. Population Reference Bureau. (2007). Population Bulletin. Immigration and America’s Black Population, 62(4). Washington, DC: Kent, M. M. Lawson, S. (1991). Multi-cultural awareness project. The organization and implementation of a “World steel drum ensemble”. Nova University. (ED 338783) New York City Department of Planning Population Division. (2004). The newest new yorkers 2000. Immigrant New York in the New Millennium (NYC DCP #04-09) McCalman, L. (2003). Steelband in schools: The instructor dependency model vs. the teacher transferency model. New Era in Education, 82(2), 42-50. Retrieved from http://www.pan-jumbie.com/uploads/papers/paninschools.pdf Mediageneration (2009, December 12). Yonder Come Day [Video File]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JOfPJASs-Is&feature=related Morin, F. (1989). Elementary school steelband: A curriculum and instructional plan for canadian schools. University of North Dakota. (ED 401183) Morton, C. (2001). Boom diddy boom boom: Critical multiculturalism and music education. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 9 (1), 32-41. Nachmanovitch, S. (1991). Free play. New York: Tarcher. Nathaniel, D. (2006). Finding an “equal” place: How the designation of the steelpan as the national instrument heightened identity relations in trinidad and tobago (Doctoral) 59 Dissertation, Florida State University, 2006). Retrieved from http://www.panjumbie.com/index.php?page=articles-papers Nkrumah, K. (1970). Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology of De-Colonisation. London: Heinemann. Pan: Strategic plan for sustainable development. (n.d.) Retrieved from http:// www.pantrinbago.co.tt/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2 53:strategic-plan-for-pan&catid=41:feature-articles&Itemid=177 Pleasant, D. (2004). The Drum is a Voice. Brooklyn Rail, 1. Retrieved from http:// www.brooklynrail.org/2004/01/music/the-drum-is-a-voice Popkewitz, T. S. (1980). Global education as a slogan system. Curriculum Inquiry, 10 303-316. doi:10.2307/1179617 (3), Rodney, W. (1972 ). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Washington, DC. Howard University Press. Schmidt, P. (2005). Music education as transformative practice: Creating new frameworks for learning music through a freirian perspective. Visions of Research in Music Education, 6(1). Retrieved from http://www.rider.edu/~vrme/ v6n1/vision/schmidt_2005.pdf Sleeter, C. E. (1996). Multicultural education as a social movement. Theory into Practice, 35(4), 239-247. doi:10.1080/00405849609543730 Tanner, C. (2007). The steel band game plan: Strategies for the starting, building, and maintaining your pan program. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Education. Thomas, K. P. (1999). Panriga. Port of Spain, Original World Press. Walrond, J. (2007). Steelpan, caribbean identity and culturally relevant adult programs. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Education, 2(2), 22-39. Retrieved from http:// ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/JCIE Wang, J, & Humphreys, J. T. (2009). Multicultural and popular music content in an american music teacher education program. International Journal of Music Education, 27, 19-36. doi: 10.1177/0255761408099062 Williams, K. (2008). Steel bands in american schools: What they do and why they’re growing!: Steel drum ensembles promote multicultural music education and attract a wide range of students. Music Educators Journal, 94, 52-57. doi: 10.1177/00274321080940040107 60