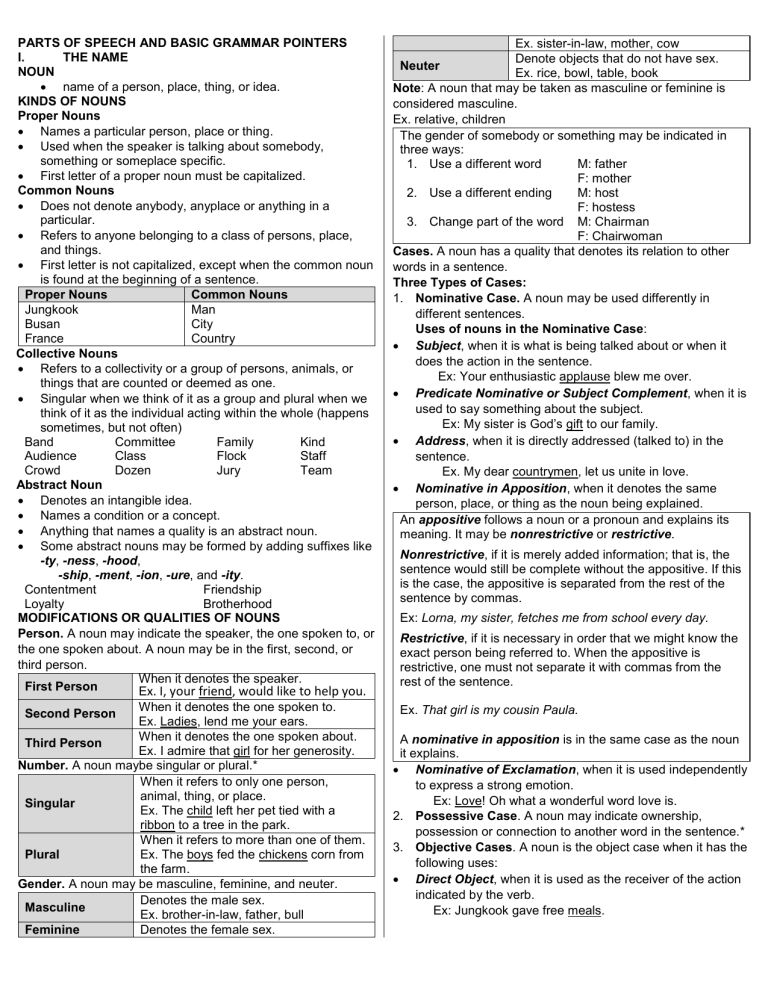

PARTS OF SPEECH AND BASIC GRAMMAR POINTERS I. THE NAME NOUN name of a person, place, thing, or idea. KINDS OF NOUNS Proper Nouns Names a particular person, place or thing. Used when the speaker is talking about somebody, something or someplace specific. First letter of a proper noun must be capitalized. Common Nouns Does not denote anybody, anyplace or anything in a particular. Refers to anyone belonging to a class of persons, place, and things. First letter is not capitalized, except when the common noun is found at the beginning of a sentence. Proper Nouns Common Nouns Jungkook Man Busan City France Country Collective Nouns Refers to a collectivity or a group of persons, animals, or things that are counted or deemed as one. Singular when we think of it as a group and plural when we think of it as the individual acting within the whole (happens sometimes, but not often) Band Committee Family Kind Audience Class Flock Staff Crowd Dozen Jury Team Abstract Noun Denotes an intangible idea. Names a condition or a concept. Anything that names a quality is an abstract noun. Some abstract nouns may be formed by adding suffixes like -ty, -ness, -hood, -ship, -ment, -ion, -ure, and -ity. Contentment Friendship Loyalty Brotherhood MODIFICATIONS OR QUALITIES OF NOUNS Person. A noun may indicate the speaker, the one spoken to, or the one spoken about. A noun may be in the first, second, or third person. When it denotes the speaker. First Person Ex. I, your friend, would like to help you. When it denotes the one spoken to. Second Person Ex. Ladies, lend me your ears. When it denotes the one spoken about. Third Person Ex. I admire that girl for her generosity. Number. A noun maybe singular or plural.* When it refers to only one person, animal, thing, or place. Singular Ex. The child left her pet tied with a ribbon to a tree in the park. When it refers to more than one of them. Plural Ex. The boys fed the chickens corn from the farm. Gender. A noun may be masculine, feminine, and neuter. Denotes the male sex. Masculine Ex. brother-in-law, father, bull Feminine Denotes the female sex. Ex. sister-in-law, mother, cow Denote objects that do not have sex. Neuter Ex. rice, bowl, table, book Note: A noun that may be taken as masculine or feminine is considered masculine. Ex. relative, children The gender of somebody or something may be indicated in three ways: 1. Use a different word M: father F: mother 2. Use a different ending M: host F: hostess 3. Change part of the word M: Chairman F: Chairwoman Cases. A noun has a quality that denotes its relation to other words in a sentence. Three Types of Cases: 1. Nominative Case. A noun may be used differently in different sentences. Uses of nouns in the Nominative Case: Subject, when it is what is being talked about or when it does the action in the sentence. Ex: Your enthusiastic applause blew me over. Predicate Nominative or Subject Complement, when it is used to say something about the subject. Ex: My sister is God’s gift to our family. Address, when it is directly addressed (talked to) in the sentence. Ex. My dear countrymen, let us unite in love. Nominative in Apposition, when it denotes the same person, place, or thing as the noun being explained. An appositive follows a noun or a pronoun and explains its meaning. It may be nonrestrictive or restrictive. Nonrestrictive, if it is merely added information; that is, the sentence would still be complete without the appositive. If this is the case, the appositive is separated from the rest of the sentence by commas. Ex: Lorna, my sister, fetches me from school every day. Restrictive, if it is necessary in order that we might know the exact person being referred to. When the appositive is restrictive, one must not separate it with commas from the rest of the sentence. Ex. That girl is my cousin Paula. A nominative in apposition is in the same case as the noun it explains. Nominative of Exclamation, when it is used independently to express a strong emotion. Ex: Love! Oh what a wonderful word love is. 2. Possessive Case. A noun may indicate ownership, possession or connection to another word in the sentence.* 3. Objective Cases. A noun is the object case when it has the following uses: Direct Object, when it is used as the receiver of the action indicated by the verb. Ex: Jungkook gave free meals. Object of a Preposition, when it is what the preposition in the sentence refers to. It usually follows the preposition. Ex: Gina made tea in the kitchen. Objective in Apposition, when the noun is used as an appositive of (explains or specifies) a noun that is in the objective case, then that noun is in the objective case as well, functioning as an objective in apposition. Ex. The audience crowded around the singer Lea Salonga. Indirect Object, when a noun refers to whom or for whom an action is done. It receives whatever is named by the direct object. It usually found between the verb and the direct object. Ex: Cindy brought her nephew a present. Some verbs which may take both a direct and indirect object: assign get pardon send bring give pay show buy grant promise sing deny hand read teach do lend refuse tell forbid offer remit wish forgive owe sell write Adverbial Objective, when a noun is used as an adverbthe part of speech that tells us when, where, why, how much, how far and how long. Ex: The rope stretched ten yards. Retained Object, when the verb changes from active to passive but retains its direct object. Active: The librarian lent the boy the books. Passive: The boy was lent the books by the librarian. Objective Complement, when a noun is used to explain the direct object and complete the meaning of the verb. Ex: I choose the artist Rogel. Some verbs that may take objective complements: appoint consider choose name call declare make elect Cognate Object, when a noun that repeats the meaning implied by the verb is a direct object. Ex: We ran an exhilarating run. II. THE SUB Pronouns are words that take the place of nouns. Most pronouns have an antecedent, or a noun that has already been specified previously, though some have no antecedent (e.g. everyone). These words take away the monotony of repeating the nouns repeatedly. KINDS OF PRONOUNS Personal Pronouns are pronouns that replace persons or things. First Person Case Singular Plural Nominative i we Possessive my*, mine our* Objective me us Second Person Nominative you you Possessive your* your*, yours Objective you you Third Person Nominative he, she, it they Possessive his*, her*, hers, its their*, their Objective him, her, it them Compound Personal Pronouns are formed by adding the suffixes -self or -selves to certain personal pronouns. Forms of the Compound Personal Pronouns Singular Plural First Person myself ourselves Second Person yourself yourselves Third Person himself, herself, themselves itself TYPES OF COMPOUND PERSONAL PRONOUNS Intensive Pronoun. Used to give emphasis to the noun or pronoun that it replaces or refers to. Ex: She herself must put things to right. The members themselves are to blame. Reflexive Pronoun. Used to indicate that the subject of the sentence also receives the action of the verb. That is, the Subject is also the Object. Ex: I bathed myself. You must love yourself. Note: When pronouns are combined, the reflexive will take the first person. Ex: Greg, Rita and I gave ourselves a pat on the back. But when there is no first person, the reflexive will take the second person. Ex: You and Rose injured yourself. The indefinite pronoun one has its own reflexive form but the other indefinite pronouns don’t. Interrogative Pronouns: Introduce Questions. Used to ask questions. There are three interrogative pronouns: who, which, and what. They are used in Direct and Indirect Questions. Direct Questions Indirect Questions Who did this? My friend asked who did this. Which dress do you think? Beatrice asked which dress you like. What kind of work is that? The boss wondered what kind of work that is. Interrogative Pronouns also sometimes act as Determiners or words which make a noun. If interrogative pronouns are used this way, you’ll know that they will be followed by a noun. In this sense, they act as like adjectives. Ex: Which car did you want? What mood is he in? Relative Pronounswho, which, what, and thatrelate groups of words to nouns or other pronouns. Function as conjunctions by joining to its antecedent the subordinate clause of which it is a part. Ex: The student who studies hardest usually becomes the best in his class. Forms of the Who Singular Plural Nominative who who Possessive whose whose Objective whom whom Compound Relative Pronoun. Formed by adding the suffix ever or -soever to who, whom, which, and what. Ex: Do whatever you have to do. (Do the things which you have to do.) Whatsoever wishes to continue must do so. (The one who wishes to continue must do so.) Adjective Pronouns are pronouns that may be used as adjectives. They modify the noun that follows them. Pronouns Adjective Pronoun These are cute. These puppies are cute. Many were angry. Many people were angry. Each may choose a gift. Each child may choose a gift. TYPES OF ADJECTIVE PRONOUNS Demonstrative Pronouns. Pronoun that identify or point to a definite person, place or thing. They are this, that, and those. This is my pet dog. Ex: That is my boyfriend. These are the eggs I bought. Note: This and these are used for object near at hand. That and those are used to point at objects far from the speaker. Indefinite Pronouns. Pronouns that point out no particular person, place or thing. That is, they do not act as substitutes to specific nouns but stand as nouns themselves. Commonly Used Indefinite Pronouns all everyone one another everything same any few several anybody many some anyone much somebody anything no one someone both nobody something everybody none such Distributive Pronouns. Pronouns that refer to each person, place or thing separately. They are each, either, and neither. Each has made his choice. Ex: Either will do. Neither is satisfactory. Possessive Pronouns. Pronouns used to denote possession or ownership by the speaker, the person spoken to, or the person or thing spoken about. Note: Independent Possessive are possessive pronouns that may be used alone to take the place of nouns. They are mine, ours, yours, hers, its, and theirs. CASE OF PRONOUNS Nominative Case. Pronouns used in the following ways are in the nominative case. 1. Subject of a Verb She and I arrived safely. Note: Do not use me which is in the objective case since the pronoun is the subject. 2. Predicate Nominative/Subjective Complement It was he. Note: Do not use him which is in the objective case since the pronoun is used as a predicate nominative. Objective Case. Pronouns used in the following ways are in the objective case: 1. Direct Object Mother loves us. Note: Do not use we which is in the subject case since the pronoun here is used as a direct object of the verb loves. 2. Indirect Object James promised her a cake. Note: Do not use she which is in the nominative case since the pronoun here is used as an indirect object of the verb promised. 3. Object of a Preposition I received a package from them. Note: Do not use they which is in nominative case since the pronoun here is used as an object of the preposition from. CORRECT USE OF PRONOUNS 1. Pronouns used after the conjunctions than and as should be if the same case as the word with which it is compared. Lorna is as intelligent as he. Note: He is compared to Lorna, which is in the nominative case. Thus, he must be used which is in the nominative case. He has worked harder than they. Note: They is compared to He, which is in the nominative case. Thus, they should be used so that it may conform to the case of the pronoun it is compared with. We like Joseph better than him. Note: Him is compared to Joseph, which is a direct object and is thus in the objective case. Therefore, him which is in the objective case as well should be used. 2. The interrogative pronoun who is used when the sentence requires a pronoun in the nominative case. Whom is used when the sentence requires a pronoun to be in the objective case. Who arrived safely? Note: The pronoun stands for the subject of the verb in this sentence. A pronoun used as a subject is in the nominative case. Therefore, the correct interrogative pronoun is who, which is int the normative case. To whom do you send your love? Note: The pronoun underlined was used as an object of the preposition to. Remember that the object of a preposition should be in the objective case. Therefore, whom must be used instead of who. Whom have you talked to? Note: The pronoun underlined was used as an object of the preposition to. 3. The relative pronoun who is used when the pronoun is the subject of a verb. Whom is used when the pronoun is the object of a verb or a preposition. I have seen Larry who won the game for the school. Note: Remember that a relative pronoun’s case depends on the way the pronoun is used in the subordinate clause. In this sentence the pronoun is used as the subject of the verb won in the subordinate clause. Thus, the pronoun must be in the nominative case. The guy whom we have invited did not come. Note: The pronoun in this instance is used as an object of the verb have invited. Thus, the pronoun must be in the objective case. The man for whom she has dressed up has arrived. Note: The pronoun in this instance is used as an object of the preposition for. Thus, it is necessary that the pronoun be in the objective case. 4. A pronoun must agree with its antecedent in person, number, and gender. A pronoun must have the same person (whether it be first, second, or third person) as the noun or pronoun it refers to. It must also be singular or plural, depending on whether the antecedent is singular or plural. Then the pronoun must be masculine, feminine, or neuter depending on whether the antecedent is feminine, masculine, or neuter. I am grooming myself for the ball. Antecedent = I, which is singular and in the first person Pronoun = myself, which is singular and in the first person Sheila hugged her father. Antecedent = Sheila, which is feminine, singular, and in the first person. Pronoun = her, which is feminine, singular, and in the first person. 5. If the distributive pronouns each, either, and neither, as well as the indefinite pronouns one, anyone, no one, nobody, anybody, everyone, everybody, someone, and somebody are used as the antecedents (or the word referred to), the pronouns referring to them must be singular. Everyone must bring his date. 6. If the indefinite pronouns like all, both, few, many, several, and some which are generally plural are used as antecedent, the pronouns used after should also be plural. All were afraid of their teachers. 7. Compound personal pronouns also agree with their antecedents in person, number, and gender. Intensive The teacher himself gave her money. Reflexive The teacher made herself give the money away. 8. When a sentence contains a negative, such as not or never, use anything too express a negation. Use nothing only if the sentence does not contain a negative already. I can’t do anything. Note: Using anything makes the sentence mean that the speaker cannot do anything. Using nothing instead of anything would make the sentence mean that the speaker can indeed do something. III. THE DESCRIPTORS Adjectives are words that describe or modify another person or thing in the sentence. Adjective describe or modify either nouns or pronouns. CLASSES OF ADJECTIVES Descriptive Adjectives. An adjective that describes a noun or a pronoun. There are also proper and common adjectives. Proper Adjective. An adjective that is formed from a proper noun. Ex: Victorian Gown, Spanish Bread Common Adjective. An adjective that expresses the ordinary qualities of a noun or pronoun. Ex: Frilly gown, Delicious bread Limiting Adjectives. An adjective that either points out an object or denotes a number. Numerical Adjective. An adjective that denotes exact number. Ex: five ducks, ten fingers Pronominal Adjective. An adjective that may also by used as a pronoun. Ex: either cat, that bag Articles. Like the, a, and an are also limiting adjectives because they denote whether a noun is definite or indefinite. Ex: the song, a memory, an undertaker Rule of thumb: If pronouns modify nouns, then they are considered as adjectives at that moment. Thus, aside from the known adjective pronouns, interrogative pronouns that point to a noun or a pronoun are also considered as pronominal adjectives. Ex: Which girl did you say he liked? What mood is he in? Whose turtle won the race? POSITION OF ADJECTIVES Adjectives nearly always appear immediately before the noun or noun phrase that they modify. considerable efforts Ex: huge appetite Sometimes they appear in a string of adjectives, and when they do, they appear in a set order according to category. The following list show the usual order of adjectives when they appear in a string. There are exceptions, of course but this is the usual rule. I. Determiners – articles and other limiters. II. Observation – post determiners and limiter adjectives (e.g., real hero, a perfect idiot) and adjectives subject to subjective measure (e.g., beautiful, interesting) III. Size and Shape – adjectives subject to objective measure (e.g., wealthy, large, round) IV. Age – adjectives denoting age (e.g., young, old, new, ancient) V. Color – adjectives denoting color (e.g., yellow, blue, pink) VI. Origin – denominal adjectives denoting source of noun (e.g., French, American, Korean) VII. Material – denominal adjectives denoting what something is made of (e.g., woolen, metallic, wooden) VIII. Qualifier – final limiter, often regarded as part of the noun (e.g., rocking chair, hunting cabin, passenger car, book cover) When indefinite pronouns – such as something, someone, anybody – are modified by an adjective, the adjective comes after the pronoun: Anyone capable of doing something horrible to someone nice should be punished. Something wicked is coming our way. And there are certain adjectives that, in combination with certain words, are always “postpositive" or always come after the noun or pronoun they modify. The president elect, heir apparent to the Glitzy fortune, lives in New York proper. There are also adjectives that usually come after the linking verb and are thus called predicate adjectives. A-adjectives or adjectives that begin with the letter a are usually found after the linking verb and thus show up as predicate adjectives. Common a-adjectives ablaze alert aloof awake afloat alike ashamed aware afraid alive asleep aghast alone averse The children were ashamed. The professor remained aloof. Occasionally, however, you will find a -adjective before the word they modify: the alert patient the aloof physician Most of them, when found before the word they modify, are themselves modified: the nearly awake student the terribly alone scholar And a-adjectives are sometimes modified by “very much”: very much afraid very much alone very much ashamed Basic rules in the position of adjectives in a sentence: 1. The usual position of adjectives is before the noun. They are called attributive adjectives if they follow this rule. Ex: The humble boy gave his thanks. 2. There are adjectives that follow a linking verb, completing the thought expressed. These adjectives show up as predicate adjectives. Ex: The boy was cold and afraid. 3. An adjective may follow the direct object and at the same time complete the thought expressed by the transitive verb. These adjectives show up as objective complements. Ex: We consider that work excellent. Ex: COMPARISON OF ADJECTIVES The Correct Use of the Positive, Comparative and Superlative Degrees Adjectives can express different degrees of modification. Aiza Mae is a rich woman, but Khryss is richer than Gladys, and Totchelyn is the richest woman in town. The degrees of comparison are known as the positive, the comparative, and the superlative. Positive – denotes the quality of noun or pronoun. There is no comparison here. Ex: sad girl Comparative – denotes the quality in a greater or lesser degree. Ex: sadder girl Superlative – denotes the quality in the greatest or least degree. Ex: saddest girl We use the comparative for comparing two things and the superlative for comparing three or more things. Notice that the word than frequently accompanies the comparative and the word the precedes the superlative. The inflected suffixes -er and -est suffice to form most comparatives and superlatives, although we need -ier and -iest when two-syllable adjective ends in y (happier and happiest). When -er, -est, -ier, and -iest are not suitable, we use more and most, or less and least when an adjective has more than one syllable. Positive Comparative Superlative wide wider widest lovely lovelier loveliest gorgeous more gorgeous most gorgeous handsome less handsome least handsome Some adjective are irregular when it comes to forming the comparative and the superlative. These are the most frequently used: Positive Comparative Superlative little less least bad, ill, evil worse worst good better best many, much more most late later, latter latest, last far farther farthest fore former foremost, first old older, elder oldest, eldest near nearer nearest, next further furthest inner innermost, inmost outer outermost, outmost upper uppermost, upmost Note: The positive for further, inner, outer, and upper do not exist that is why they are blank. Some adjectives do not take to comparison absolute ideal adequate impossible chief inevitable dead main devoid manifest entire minor eternal paramount fatal perpendicular final perpetual preferable principal stationary sufficient supreme unanimous unbroken universal Both adverbs and adjectives in their comparative and superlative forms can be accompanied by premodifiers, single words and phrases that intensify the degree. We were a lot more careful this time. He works a lot less careful than the other jeweler in town. We like his work so much better. You’ll get your watch back all the faster. The same process can be used to downplay the degree: The weather this week has been somewhat better. He approaches his schoolwork a little less industriously than his brother does. And sometimes a set phrase, usually an informal noun phrase, is used for this purpose: He arrived a whole lot sooner than we expected. That’s a heck of a lot better. If the intensifier very accompanies the superlative, a determiner is also required: She is wearing her very finest outfit for the interview. They’re doing the very best they can. Occasionally, the comparative or superlative form appears with a determiner and the thing being modified is understood: Of all the wines produced in Connecticut, I like this one the most. The quicker you finish this project, the better. Of the two brothers, he is by far the faster. The Correct Use of Fewer and Less When making a comparison between quantities we often must make a choice between the words fewer and less. Generally, when we are talking about countable things, we use the word fewer; when ae are talking about measurable quantities that we cannot count, we use the word less. She had fewer chores, but she also had less energy. We do, however, use less when referring to statistical or numerical expressions. In these situations, it is possible to regard the quantities as sums of countable measures. It’s less than twenty kilometers to the city. The shark’s less than 10 feet long. Your essay should be a thousand words or less. We spent less than a thousand pesos on our excursion. The Proper Use of Than When making a comparison with than, do we end with a subject form or object for? Which of the following expressions are correct? a. I am taller than she. b. I am taller than her. The correct response is letter a, taller than she. We are properly looking for the subject form though we leave out the verb in the second clause, is. We also want to be careful in a sentence such as “I like him better than she/her.” The she would mean that you like this person better than she likes him; the her would mean that you like this male person better than you like that female person. To avoid ambiguity and the slippery use of than, we could write, ’I like him better than she does” or “I like him better than I like her.” TRICKY ADJECTIVES The Correct Use of Good and Well In both casual speech and formal writing, we frequently have to choose between the adjective good and the adverb, well. With most verbs, there is no contest: when modifying a verb, use the adverb. He swims well. He knows only too well who the murderer is. However, when using a linking verb or a verb that has to do with the five human senses, you want to use the adjective instead. How are you? I’m feeling good, thank you. After a bath, the baby smells so good. Even after my careful paint job, this room doesn’t look good. Many careful writers, however, will use well after linking verbs relating to health, and this is perfectly all right. In fact, to say that you are good or that you feel good usually implies not only that you're OK physically but also that your spirits are high. “How are you?” “I am well, thank you.” The Proper Use of Bad and Badly When your cat died (assuming you loved your cat), did you feel bad or badly? Applying the same rule that applies to good versus well, use the adjective form after verbs that have to do with human feelings. You felt bad. If you said you felt badly, it would mean that something was wrong with your faculties for feeling. Repetition of the Article Analyze the meaning of the following sentences. The chairman and president of the company walked into the meeting. The chairman and the president of the company walked into the meeting. The first sentence (where the article the is used only before the first noun) indicates that one person is both chairman and president of the company. The second sentence (where the article the is used before each noun) indicates that the chairman and the president are two different individuals. IV. THE ACTION WORDS Verbs carry the idea of being or action in the sentence. I am a student. The students passed all their courses. Verb Phrases are groups of word used to do the work of a single verb. He could have gone abroad. She is called the “Ice Lady.” Verb Phrases can be divided into two major components: Principal verb. The main verb in the verb phrase. In the above underlined examples, the main verbs are gone and called. Auxiliary Verb. The helping verb; that which is used with the main verb to form its voice, mood and tense. Again in the above examples, the helping verbs are could have and is. Following are examples of auxiliary verbs: be are do has will might am was did had may could is were have shall can would KINDS OF VERBS ACCORDING TO FORM The principal parts of the verb are the present, the past, the present participle, and the past participle. According to the manner by which their principal parts are formed, verbs may be regular, irregular, or defective. Regular Verbs are verbs that form their past tense and their past participle by adding d or ed to the present tense. Present Past Past Participle pull pulled pulled create created created greet greeted greeted Irregular Verbs are verbs that do not form their past tense and their past participle by simply adding d or ed to the present form. Present Past Past Participle grow grew grown drink drank drunk hear heard heard wring wrung wrung cut cut cut go went gone Defective Verbs are verbs that do not have all the principal part. Present Past Past Participle beware can could may might must must ought ought shall should will would KINDS OF VERBS ACCORDING TO USE Transitive Verbs are verbs that express action which passes from a doer to a receiver. Doer Action Receiver I saw you. The monkey bit the zookeeper In some cases, the sentence is configured a different way. Active Voice: She greeted her neighbor. Passive Voice: Her neighbor was greeted by Sheila. In the first case, the verb form is greeted. In the second case, the verb form is was greeted. In both cases, however, the verb is transitive because the action passes from a doer to a receiver. Intransitive Verbs are verbs that have no receiver of their action. Doer Action Receiver The dog whined the whole night. She sat on the sofa. Without a receiver, the above sentences are still complete. Unlike transitive verbs, however, intransitive verbs are always in the active voice since there is no receiver to start a sentence in a passive voice with. Verbs become transitive and intransitive according to their use in the sentence. She gave alms to the poor. (Transitive) She regularly gave to the poor. (Intransitive) Cognate Verbs are verbs whose object repeats the meaning implied by the verb itself. They are usually intransitive verbs used transitively. Cognate means related. Cognate Verb Object She cried buckets of tears. cried tears Lydia de Vega ran a brilliant race. ran race Linking Verbs connect a subject and its complement. Sometimes called copulas, linking verbs are often forms of the verb to be, but are sometimes verbs related to the five senses (look, sound, smell, feel, taste) and sometimes verbs that somehow reflect a state of being (appear, continue, seem, become, grow, turn, prove, remain). Their main function is linking or coupling the subject with a noun, a pronoun, or an adjective. Subjective complement is a word or a group of words used to complete the meaning of a linking verb. o Predicate Nominative, if the subjective complement is a noun or a pronoun. o Predicate Adjective, subject complement is an adjective. Subject Linking Verb Subjective Complement Her dress looked stunning. PA That gentleman is the king. PN A handful of verbs that reflect a change in the state of being, are sometimes called resulting copulas. They, too, link a subject to a predicate adjective: His face turned purple. She became older. The dogs run wild. The milk has gone sour. The crowd grew ugly. THE VOICE OF A VERB Voice is that quality of a verb that indicates whether the subject is the doer or receiver of the action of the verb. Remember that only transitive verbs may be used in the passive voice. Intransitive verbs have no receivers (object) of the action. Verbs are also said to be either active or passive in voice. Active Voice denotes the subject as the doer of the action. In the active voice, the subject and verb relationship is straightforward: the subject is a be-er or a do-er and the verb moves the sentence along. Example: Subject and Doer The President of the Philippines signed the new bill into law. The professor scolded the class for an hour. Passive Voice denotes the subject as the receiver of the action. In the passive voice, the subject of the sentence is neither a do-er or a be-er, but is acted upon by some other agent or by something unnamed (when it is, it is usually named by an object of the preposition). Example: Subject and Doer The new bill was finally signed into law. The class was scolded for an hour. Statements and sentences in the passive voice abound. Notice that when you use it yourself when using a computer, the grammar check usually tells you to change it to the active voice. There is nothing inherently wrong with the passive voice, but if you can say the same thing in the active mode, do so. The passive voice does exist for a reason, however, and its presence is not always to be despised. The passive is particularly useful (even recommended) in two situations: When it is more important to draw our attention to the person or thing acted upon: The unidentified victim was apparently struck during the early morning hours. When the actor in the situation is not important: The aurora borealis can be observed in the early morning hours. THE VERB TENSE Tense is the quality of a verb which denotes the time of the action, the being, or the state of being. Simple Tenses Present Tense – signifies action, being, or state of being in present time. Past Tense - signifies action, being, or state of being in past time. Future Tense - signifies action, being, or state of being in future time. Compound Tenses Present Perfect Tense - signifies action, being, or state of being completed or perfected in present time. This is formed by prefixing the auxiliary have or has to the past participle of the verb She has written the article Past Perfect Tense - signifies action, being, or state of being completed or perfected before some definite past time. This is formed by prefixing the auxiliary had to the past participle of the verb. She had written the article before I came. Future Perfect Tense - signifies action, being. or state of being that will be completed or perfected before some specified time in the future. This is formed by prefixing the auxiliary shall have or will have to the past participle of the verb. She will have written the article before I come. THE MOOD OF THE VERB Mood or Mode is that quality of a verb that denotes the manner in which the action, the being, or the state of being is expressed. o Indicative Mood. The indicative mood of the verb is used to make a statement, to deny a fact or ask a question. The exam was easy. I did not get the prize. . What happened? The Potential Form of the Indicative Mood This is used to express permission, possibility, ability, necessity and obligation. Thus, they are formed by using the auxiliary verbs may, might, can, could, must, should and would. These are called modals. Permission You may begin. Possibility It might be so. It could happen. Ability The Philippines can do it. Necessity We must get out of this economic slump. Obligation Filipinos should start thinking of the collective good for a change. Imperative Mood. The imperative mood of the verb is used when we're feeling sort of bossy and want to give a directive, strong suggestion, or order: Get your homework done before you watch television tonight. Please include cash payment with your order form. Get out of town! Notice that there is no subject in these imperative sentences. The pronoun you (singular or plural, depending on context) is the "understood subject" in imperative sentences. Virtually all imperative sentences, then, have a second person (singular or plural) subject. The sole exception is the first person construction, which includes an objective form as subject: "Let's (or Let us) work on this thing together." Subjunctive Mood. The subjunctive mood of the verb is used in dependent clauses that do the following: 1. express a wish; 2. begin with if and express a condition that does not exist (is contrary to fact); 3. begin with as if and as though when such clauses describe a speculation or condition contrary to fact; and 4. begin with that and express a demand, requirement, request, or suggestion. She wishes her boyfriend were here. If Juan were more aggressive, he'd be a better hockey player. We would have passed if we had studied harder. He acted as if he were guilty. I requested that he be present at the hearing. Important: The words if, as if, or as though do not always signal the subjunctive mood. If the information in such a clause points out a condition that is or was probable or likely, the verb should be in the indicative mood. The indicative tells the reader that the information in the dependent clause could possibly be true. The present tense of the subjunctive uses only the base form of the verb. He demanded that his students use two-inch margins. She suggested that we be on time tomorrow. The past tense of the subjunctive has the same forms as the indicative except for the verb to be, which uses were regardless of the number of the subject. If I were seven feet tall, I'd be a great basketball player. He wishes he were a better student. If you were rich, we wouldn't be in this mess. If they were faster, we could have won that race. THE PERSON AND NUMBER OF VERBS A verb may be in the first, the second, or the third person, and either singular or plural in number. Singular Number Plural Number First Person I speak the truth. We speak the truth Second You speak the truth. You speak the truth. Person Third Person She speaks the They speak the truth. truth. He speaks the truth. SUBJECT-VERB AGREEMENT The verb must always agree with its subject in person and number. Of course, there are exceptions, as in the case of the verb be in the subjunctive mode. In this case, the verb always takes the form of were regardless of the number of the subject. (See above for the discussion). A singular subject requires a singular verb while a plural subject requires a plural verb. He likes the smell of wet grass. He is the singular subject; likes is the singular verb. The dancers dance so gracefully. Dancers is plural thus the verb dance is plural, too. The Proper Use of Doesn’t and Don’t If the subject of the sentence is in the third person and singular, doesn’t is the correct form of the verb. If the subject is in the first or second person, regardless of the number, the correct form is don’t. The girl in the yellow shirt doesn’t like Math. The volunteers don’t care about money. I don’t know what I will do. The Proper Use of There is and There are o There is (or There was or There has been) should be used when the subject that follows the verb is singular. o There are (or There were or There have been) should be used when the subject is plural. There is a lot to be done yet. There are awards to be had and medals to be won The Proper Use of Here is and Here are o Here is (or Here was or Here has been) should be used when the subject that follows the verb is singular. o Here are (or Here were or Here have been) should be used when the subject is plural. Here is food for everyone. Here are drinks for us all. The Proper Use of You as a Subject When You is the subject, the plural conjugation of verbs (are, were, have, etc.) should always be used, whether the You is meant in the singular or plural sense. You alone are the apple of my eye. (subject is singular) You (children) are the pride of your (subject is plural) school. Subject-Verb Agreement when there are Parenthetical Expressions Sometimes modifiers will get between a subject and its verb, but these modifiers must not confuse the agreement between the subject and its verb. The mayor, who has been convicted along with his four brothers on four counts of various crimes but who also seems, like a cat that has several political lives, is finally going to jail. Take note only of the subject. If the subject is singular, the verb is singular. If the subject is plural, the verb is plural. She alone among all my classmates commutes to school. Phrases such as together with, as well as, and along with are not the same as and. The phrase introduced by as well as or along with will modify the earlier word (mayor in this case), but it does not compound the subjects (as the word and would do). The mayor as well as his brothers is going to prison. The mayor and his brothers are going to jail. Subject-Verb Agreement for Compounded Positive and Negative Subjects If your sentence compounds a positive and a negative subject and one is plural, the other singular, the verb should agree with the positive subject. The department members but not the chair have decided not to teach on Valentine's Day. It is not the faculty members but the president who decides this issue. It was the speaker, not his ideas, that has provoked the students to riot. Subject-Verb Agreement for Compound Subjects Connected by and Compound subjects connected by and require a plural verb unless the subjects refer to the same person or thing, or express a single idea. The president and the chairman are now taking their seats. The president and chairman is now taking his seat. Subject-Verb Agreement for Compound Subjects Preceded by each and every Two or more singular subjects connected by and but preceded by each, every, many a, or no require a singular verb. Each man and woman was affected by the emotional speech. Many a child dreams to be a star. Subject-Verb Agreement for Compound Subjects Connected by or or nor Singular subjects connected by or or nor requires a singular verb. Neither Rowel nor Madonna wants to go first. Plural subjects connected by or or nor require a plural verb. My grandparents or my sisters are attending my graduation. When two subjects of different person or number are connected by or or nor, the verb agrees with the subject nearest to it. Joanna or her siblings are in the living room. Neither my friends nor I am watching the late-night movie. Subject-Verb Agreement for Collective Nouns A collective noun requires a singular verb if the idea being expressed by the subject is a single unit. It requires a plural verb if the idea expressed by the subject denotes separate individuals. Note, however, that a collective noun is usually thought of as a single unit, and thus, the verb that goes with it is usually singular. A dozen is enough. The audience were on their feet. Subject-Verb Agreement for Distributive and Indefinite Pronouns The distributive pronouns—each, either, neither—and the indefinite pronouns—everyone, anyone, nobody, somebody, everybody, someone, somebody—are always used with a singular verb. Each of us here is determined to get into a good college. Everyone here likes the thought of passing the UPCAT. Some indefinite pronouns — such as all, some — are singular or plural depending on what they're referring to. (Is the thing referred to countable or not?) Be careful choosing a verb to accompany such pronouns. Some of the beads are missing. Some of the water is gone. On the other hand, there is one indefinite pronoun, none, that can be either singular or plural; it often doesn't matter whether you use a singular or a plural verb — unless something else in the sentence determines its number. (Writers generally think of none as meaning not any and will choose a plural verb, as in "None of the engines are working," but when something else makes us regard none as meaning not one, we want a singular verb, as in "None of the food is fresh.") None of you claims responsibility for this incident? None of you claim responsibility for this incident? None of the students have done their homework. (In this last example, the word their precludes the use of the singular verb.) Subject-Verb Agreement for Special Singular and Plural Nouns Sometimes nouns take weird forms and can fool us into thinking they are plural when they are really singular and vice-versa. Some nouns are plural in form but are really singular in meaning. Some words like this are aeronautics, athletics (training), civics, economics, mathematics, statistics, measles, molasses, mumps, news and physics. Mathematics is Liza’s favorite subject. On the other hand, some words ending in -s refer to a single thing but are nonetheless plural and require a plural verb. My assets were wiped out in the depression. The average worker's earnings have gone up dramatically. Our thanks go to the workers who supported the union. Words such as glasses, pants, pliers, and scissors are regarded as plural (and require plural verbs) unless they're preceded by the phrase pair of (in which case the word pair becomes the subject). My glasses were on the bed. My pants were torn. A pair of plaid trousers is in the closet. The names of sports teams that do not end in "s" will take a plural verb: The Miami Heat have been looking … The Connecticut Sun are hoping that new talent … Subject-Verb Agreement of Fractional Expressions, Sums and Products, More Than One Fractional expressions such as half of, a part of, a percentage of, a majority of are sometimes singular and sometimes plural, depending on the meaning. They take the form of the noun they are modifying and thus are singular or plural when the noun modified is singular or plural, respectively. (The same is true, of course, when all, any, more, most, and some act as subjects.) Sums and products of mathematical processes are expressed as singular and require singular verbs. The expression more than one (oddly enough) takes a singular verb: "More than one student has tried this." Some of the voters are still angry. A large percentage of the older population is voting against her. Two-fifths of the troops were lost in the battle. Subject-Verb Agreement of Money When the subject of the sentence is money expressed in currency, the verb should be singular. A hundred pesos is not enough as a daily salary. Five hundred dollars was all she was able to save. USES OF SHALL AND WILL Shall and Will In the future tense of verbs, we use shall in the first person and will in the second and third persons to express simple futurity or expectation. If we wish to indicate an act of the will, promise or determination on the part of the speaker, we use will in the first person and shall in the second and third persons. Expectation/Simple Futurity Determination/Promise I shall go to the gym I will go to the gym tomorrow. tomorrow. You will attend the party. You shall attend the party. She will be waiting. She shall be waiting. Should and Would The same rule as applies on shall and shall applies to should and would. To indicate an expectation or simple futurity, use should in the first person and would in the second and third persons. To indicate determination on the part of the speaker, use would in the first person and should in the second and third persons. Expectation/Simple Futurity Determination/Promise I should be glad to help you. I would be glad to help you. You would cover for me. You should cover for me. They would love the idea. They should love the idea. Should can mean “ought to”. When meant this way, should is frequently used in all three persons. The youth should love their country. Would can be used to express a wish or customary action. When thus meant, would is used in all three persons. I would often sit here alone and listen to the music. Would that you could hear the music I listen to. Shall and Will in Questions Shall is always used to ask a question when the subject is in the first person. In the second and third persons whichever word is expected in the reply is used in asking the question. Question Expected Reply Shall we dance? We shall. Will she do it? She will. TROUBLESOME VERBS (AND THEIR PRINCIPAL PARTS) Lie, lay, lain This verb means to recline or to rest. It is always intransitive. Lay, laid, laid This verb means to put or place in position. It is always transitive. Sit, sat, sat This verb means to have or to keep a seat. It is always intransitive. Set, set, set This verb means to place or fix in position. It is always transitive. Rise, rose, risen This verb means to ascend. It is always intransitive. Raise, raised, raised This verb means to lift. It is always transitive. Let, let, let This verb means to permit or allow. Leave, left, left This verb means to abandon or depart from. WORDS USED AS NOUNS AND VERBS A noun is a name-word, and a verb generally expresses action or state of being. There are words, however, that can be a noun or a verb depending on the way it is used in the sentence. She appeared in my dream. (dream used as a noun) Jose would often dream of being a famous actor. (dream used as a verb) VERBALS Verbals are words that seem to carry the idea of action or being but do not function as true verbs. They are sometimes called "nonfinite" (unfinished or incomplete) verbs. Verbals are frequently accompanied by other, related words in what is called a verbal phrase. Participle: a verb form acting as an adjective. The running dog chased the fluttering moth. A present participle (like running or fluttering) describes a present condition; a past participle describes something that has happened: The completely rotted tooth finally fell out of his mouth. The distinction can be important to the meaning of a sentence; there is a huge difference between a confusing student and a confused student. Infinitive: the root of a verb plus the word to. To sleep, perchance to dream. A present infinitive describes a present condition: I like to sleep. The perfect infinitive describes a time earlier than that of the verb: I would like to have won that game. The Split Infinitive If there is one error in writing that your boss or history prof can and will pick up on, it's the notorious split infinitive. An infinitive is said to be "split" when a word (often an adverb) or phrase sneaks between the to of the infinitive and the root of the verb: "to boldly go," being the most famous of its kind. The argument against split infinitives (based on rather shaky historical grounds) is that the infinitive is a single unit and, therefore, should not be divided. Because it raises so many readers' hackles and is so easy to spot, good writers, at least in academic prose, avoid the split infinitive. Instead of writing "She expected her grandparents to not stay," then, we could write "She expected her grandparents not to stay." Sometimes, though, avoiding the split infinitive simply isn't worth the bother. There is nothing wrong, really, with a sentence such as the following: He thinks he'll be able to more than double his salary this year. The Oxford American Desk Dictionary, which came out in October of 1998, says that the rule against the split infinitive can generally be ignored, that the rule "is not firmly grounded, and treating two English words as one can lead to awkward, stilted sentences." ("To Boldly Go," The Hartford Courant. 15 Oct 1998.) Opinion among English instructors and others who feel strongly about the language remains divided, however. Today's dictionaries allow us to split the infinitive, but it should never be done at the expense of grace. Students would be wise to know their instructor's feelings on the matter, workers their boss's. Gerund: a verb form, ending in -ing, which acts as a noun. Running in the park after dark can be dangerous. Gerunds are frequently accompanied by other associated words making up a gerund phrase ("running in the park after dark"). Gerunds and gerund phrases are nouns, so they can be used in any way that a noun can be used: as subject: Being king can be dangerous for your health as object of the verb: He didn't particularly like being king. as object of a preposition: He wrote a book about being king. V. THE INTENSE WORDS An adverb is a word that modifies a verb, an adjective, or another adverb. Adverbs often function as intensifiers, conveying a greater or lesser emphasis to something. Intensifiers are said to have three different functions: they can emphasize, amplify, or downtone. Here are some examples: Emphasizers: I really don't believe him. He literally wrecked his mother's car. She simply ignored me. They're going to be late, for sure. Amplifiers: The teacher completely rejected her proposal. I absolutely refuse to attend any more faculty meetings. They heartily endorsed the new restaurant. I so wanted to go with them. We know this city well. Downtoners: I kind of like this college. Joe sort of felt betrayed by his sister. His mother mildly disapproved of his actions. We can improve on this to some extent. The boss almost quit after that. The school was all but ruined by the storm. CLASSIFICATIONS OF ADVERBS Classifications According to Meaning Adverbs may be classified according to their meaning. Adverbs of Manner (answer the question how or in what manner) She moved slowly and spoke quietly. Adverbs of Place (answer the question where). She has lived on the island all her life. She still lives there now. Adverbs of Frequency (answer the question how often) She takes the boat to the mainland every day. She often goes by herself. Adverbs of Degree (answer the question how much or how little) I’m half finished with my project. I’m much obliged Adverbs of Time (answer the question when) She tried to get back before dark. It's starting to get dark now. She finished her tea first. She left early. Adverbs of Purpose (answer the question why or for what purpose) He drives her boat slowly to avoid hitting the rocks. She shops in several stores to get the best buys. Classifications According to Use Simple Adverbs A simple adverb is an adverb used merely as a modifier. She does not think about it much. Interrogative Adverbs An interrogative adverb is an adverb used in asking questions. The interrogative adverbs are how, when, where, and why. Conjunctive Adverbs A conjunctive adverb is an adverb that does the work of an adverb and a conjunction. The principal conjunctive adverbs are after, until, as, when, before, where, since, and while. We played poker while we were there. While tells when the action happened and is therefore an adverb. However, it also connects the clause while we were there with the verb played and is therefore a conjunction. Relative Adverbs A relative adverb is a word that does the work of an adverb and a relative pronoun. The principal relative adverbs are when, where, and why. A home where prayers are said is a spiritually-content one. Since where tells a place of the action, it is an adverb. However, as it joins the subordinate clause where prayers are observed to the noun home which is the antecedent of where, it also does the work of a relative pronoun. Adverbial Objectives An adverbial objective is a noun that expresses time, distance, measure, weight, value or direction, and performs the function of adverbs. The sun beat on the laborers’ backs all day. In the above example, day, a noun, tells how long the sun beat on the laborers’ backs. The noun day modifies the verb beat and thus performs the function of an adverb. COMPARISON OF ADVERBS Regular Comparison Some adverbs form the comparative by adding –er to the positive; and the superlative degree by adding – est to the positive degree. Positive Comparative Superlative fast faster fastest often oftener oftenest Other adverbs, particularly those ending in –ly, form the comparative degree by adding more or less to the positive; and the superlative degree by adding most or least to the positive. Positive Comparative Superlative frequently more frequently most frequently legibly less legibly least legibly Irregular Comparison Some adverbs are compared irregularly. In this case it is necessary to learn the comparative and superlative degrees. Positive Comparative Superlative badly worse worst far farther farthest forth further furthest little less least much more most well better best Many adverbs denoting time and place (here, now, then, when, where, again, always, down, above) and adverbs expressing absoluteness or completeness (round, eternally, universally, never, perfectly, forever) cannot be compared. Pre-modifiers Adverbs (as well as adjectives) in their various degrees can be accompanied by premodifiers: She runs very fast. We're going to run out of material all the faster. THE CORRECT USE OF ADVERBS Distinguishing Between Adjectives and Adverbs Adjectives modify nouns and pronouns. Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs. Sometimes, however, the function of a word in the sentence is not so very obvious and one gets confused as to whether a word is a predicate adjective (when it modifies the subject) or an adverb that modifies the verb, an adjective or another verb. There is a rule of thumb to easily distinguish one from the other. Predicate adjectives are used only with linking verbs (be and its forms, appear, become, continue, feel, grow, look, remain, seem, smell, sound and taste). Gretchen looked happy. (equivalent to Gretchen was happy, and is thus an adjective.) Gretchen looked closely at the book. (tells how Gretchen looked at the book and is thus an adverb) Gretchen looked radiantly lovely. (tells how lovely and is thus an adverb) “Farther” and “Further” “Farther” denotes distance. “Further” denotes an addition. Both words may be used either as adjectives or adverbs. The farther you go, the better. The facilitator explained the rules further. Uses of There “There” may be an adverb denoting place, or it may be an expletive used to introduce a sentence. There is the gift. There is something missing. In the first sentence, “there” is part of the sentence. In the second sentence, the expletive is not necessary for it merely introduces the subject to follow the predicate verb. Thus it can be removed from the sentence. The two sentences above can be rewritten as: The gift is there. Something is missing. ADVERBIAL CLAUSES AND ADVERBIAL PHRASES If a group of words containing a subject and verb acts as an adverb (modifying the verb of a sentence), it is called an adverb clause: When this class is over, we're going to the movies. When a group of words not containing a subject and verb acts as an adverb, it is called an adverbial phrase. Prepositional phrases frequently have adverbial functions (telling place and time, modifying the verb): He went to the movies. She works on holidays. They lived in Canada during the war. Infinitive phrases can act as adverbs (usually telling why): She hurried to the mainland to see her brother. The senator ran to catch the bus. But there are other kinds of adverbial phrases: He calls his mother as often as possible. CORRECT POSITION OF ADVERBS One of the hallmarks of adverbs is their ability to move around in a sentence. Adverbs of manner are particularly flexible in this regard. Solemnly, the minister addressed her congregation. The minister solemnly addressed her congregation. The minister addressed her congregation solemnly. Adverbs of frequency may appear before the main verb: I never get up before nine o'clock between the auxiliary verb and the main verb: I have rarely written to my brother without a good reason. before the verb used to: I always used to see him at his summer home. Indefinite adverbs of time may appear either before the verb, or He finally showed up for batting practice. between the auxiliary and the main verb: She has recently retired. Inappropriately placed adverbs Adverbs can sometimes attach themselves to, and thus modify words that they ought not to modify. They reported that Giuseppe Balle, a European rock star, had died on the six o'clock news. Clearly, it would be better to move the underlined modifier to a position immediately after "they reported" or even to the beginning of the sentence — so the poor man doesn't die on television. Misplacement can also occur with very simple modifiers, such as only and barely: She only grew to be four feet tall. It would be better if "She grew to be only four feet tall." The Order of Multiple Adverbs There is a basic order in which adverbs will appear when there is more than one. I. Verb II. Manner III. IV. V. VI. Place Frequency Time Purpose Jungkook walks impatiently into town every afternoon before supper to get a newspaper. In actual practice, of course, it would be highly unusual to have a string of adverbial modifiers beyond two or three (at the most). Because the placement of adverbs is so flexible, one or two of the modifiers would probably move to the beginning of the sentence: "Every afternoon before supper, Jungkook impatiently walks into town to get a newspaper." When that happens, the introductory adverbial modifiers are usually set off with a comma. More Notes on Adverb Order As a general principle, shorter adverbial phrases precede longer adverbial phrases, regardless of content. In the following sentence, an adverb of time precedes an adverb of frequency because it is shorter (and simpler): Jungkook takes a brisk walk before breakfast every day of his life. A second principle: Among adverbial phrases of the same kind (manner, place, frequency, etc.), the more specific adverbial phrase comes first: My grandmother was born in a sod house on the plains of northern Nebraska. She promised to meet him for lunch next Tuesday. A third principle: Bringing an adverbial modifier to the beginning of the sentence can place special emphasis on that modifier. This is particularly useful with adverbs of manner: Slowly, ever so carefully, Jesse filled the coffee cup up to the brim, even above the brim. Occasionally, but only occasionally, one of these lemons will get by the inspectors. Special Cases on Positioning Adverbs 1. “Enough” The adverbs enough and not enough usually take a postmodifier position: Is that music loud enough? These shoes are not big enough. In a roomful of elderly people, you must remember to speak loudly enough. Notice, though, that when enough functions as an adjective, it can come before the noun: Did she give us enough time? The adverb enough is often followed by an infinitive: She didn't run fast enough to win. 2. “Too” The adverb too comes before adjectives and other adverbs: She ran too fast. She works too quickly. If too comes after the adverb it is probably a disjunct (meaning also) and is usually set off with a comma: Jungkook works hard. He works quickly, too. The adverb too is often followed by an infinitive: She runs too slowly to enter this race. Another common construction with the adverb too is too followed by a prepositional phrase — for + the object of the preposition — followed by an infinitive: This milk is too hot for a baby to drink. VI. PREPOSITIONS, CONJUNCTIONS, INTERJECTIONS PREPOSITIONS A preposition is a word or a group of words that describes a relationship between its object and another word in a sentence. In the following sentence, on describes the relationship between the verb ride and the object of the preposition (which is a noun) bus. Do not ride on that bus. The following is a list of the most commonly used prepositions: about behind from through above beside in throughout across between into to after beyond near toward against by of under among down off until around during on up at except over with before for past 1. The Object of a Preposition The object of a preposition is a noun, a pronoun or a group of words used as a noun. I run in the park every morning. (in + noun) I always run into you. (into + pronoun) We took the stool from under the desk. (from + phrase) She passed near where you stood. (near + clause) 2. Words Used as Adverbs and Prepositions An adverb tells how, when, and where. A preposition shows the relation between its objects and some other word in the sentence. I would like to move in by the end of the month. (adverb) I am just in the house. (preposition) 3. The Correct Use of Prepositions Prepositions of Time: at, on, and in We use at to designate specific times. The train is due at 12:15 p.m. We use on to designate days and dates. My brother is coming on Monday. We're having a party on the Fourth of July. We use in for nonspecific times during a day, a month, a season, or a year. She likes to jog in the morning. It's too cold in winter to run outside. He started the job in 1971. He's going to quit in August. Prepositions of Place: at, on, and in We use at for specific addresses. Grammar English lives at 55 Boretz Road in Durham. We use on to designate names of streets, avenues, etc. Her house is on Boretz Road. And we use in for the names of land-areas (towns, counties, states, countries, and continents). She lives in Durham. Durham is in Windham County. Windham County is in Connecticut. Prepositions of Location: in, at, and on and No Preposition IN AT ON NO PREPOSITION (the) bed* class* the bed* downstairs the home the ceiling downtown bedroom the library* the floor inside the car the office the horse outside (the) class* school* the plane upstairs the library* work the train uptown school* *You may sometimes use different prepositions for these locations. Prepositions of Movement: to and No Preposition We use to in order to express movement toward a place. They were driving to work together. She's going to the dentist's office this morning. Toward and towards are also helpful prepositions to express movement. These are simply variant spellings of the same word; use whichever sounds better to you. We're moving toward the light. This is a big step towards the project's completion. With the words home, downtown, uptown, inside, outside, downstairs, upstairs, we use no preposition. Grandma went upstairs. Grandpa went home. They both went outside. Prepositions of Time: for and since We use for when we measure time (seconds, minutes, hours, days, months, years). He held his breath for seven minutes. She's lived there for seven years. The British and Irish have been quarreling for seven centuries. We use since with a specific date or time. He's worked here since 1970. She's been sitting in the waiting room since two-thirty. “Between” and “Among” “Between” is used in speaking of two persons or objects. “Among” is used in speaking of more than two. I choose Group A between the two competing groups. She divided her bounty among her loyal supporters. “Beside” and “Besides” “Beside” means at the side of. “Besides” means in addition to. Come and sit beside me. Besides working days at the mall, she also worked nights at a coffee shop. “From” Use “from”, not “off of”, to indicate the person from whom something is obtained. I bought this dog from that boy. “Behind” Use “behind”, not “in back of”, to indicate location at the rear of. The vase is directly behind you. “Different From” Use “from”, not “than”, after the adjective different. Everyone is different from everybody else. “Differ From” and “Differ With” “Differ with” denotes disagreement of opinion. “Differ from” denotes differences in characteristic between persons or things. The treasurer differs with the board on the budget allocation. Candies differ from each other in color. “Within” Use “within” not “inside of” to denote the time within which something will occur. The seasons are changing within a few weeks. “Angry with” and “Angry At” Use “angry with” a person and “angry at” a thing. Sheila is very angry with Mark. George was angry at the result of the election. “Need of” Use “need of” not “need for”. My son has no further need of your services. “In” and “Into” “In” denotes position within. “Into” denotes motion or change of position. I am in the city. I am going into the building. Idiomatic Expressions with Prepositions Agree: to a proposal, with a person, on a price, in principle Argue: about a matter, with a person, for or against a proposition Compare: to to show likenesses, with to show differences (sometimes similarities) Correspond: to a thing, with a person Differ: from an unlike thing, with a person Live: at an address, in a house or city, on a street, with other people Prepositions with Nouns, Adjectives, and Verbs. Prepositions are sometimes so firmly wedded to other words that they have practically become one word. The following groups of words are considered as one preposition when used with nouns or pronouns. This occurs in three categories: nouns, adjectives, and verbs. NOUNS and PREPOSITIONS approval of fondness for need for awareness of grasp of participation in belief in hatred of reason for concern for hope for respect for confusion about interest in success in desire for love of understanding of ADJECTIVES and PREPOSITIONS afraid of fond of proud of angry at happy about similar to aware of interested in sorry for capable of jealous of sure of careless about made of tired of familiar with married to worried about VERBS and PREPOSITIONS apologize for give up prepare for ask about grow up study for ask for look for talk about belong to look forward to think about bring up look up trust in care for make up work for find out pay for worry about A combination of verb and preposition is called a phrasal verb. The word that is joined to the verb is then called a particle. Unnecessary Prepositions In everyday speech, we fall into some bad habits, using prepositions where they are not necessary. It would be a good idea to eliminate these words altogether, but we must be especially careful not to use them in formal, academic prose. She met up with the new coach in the hallway. The book fell off of the desk. He threw the book out of the window. She wouldn't let the cat inside of the house. [or use "in"] Where did they go to? Put the lamp in back of the couch. [use "behind" instead] Where is your college at? Prepositions in Parallel Form When two words or phrases are used in parallel and require the same preposition to be idiomatically correct, the preposition does not have to be used twice. You can wear that outfit in summer and in winter. The female was both attracted by and distracted by the male's dance. However, when the idiomatic use of phrases calls for different prepositions, we must be careful not to omit one of them. The children were interested in and disgusted by the movie. It was clear that this player could both contribute to and learn from every game he played. He was fascinated by and enamored of this beguiling woman. CONJUNCTIONS A conjunction is a word that connects (conjoins) parts of a sentence. It connects words, phrases, or clauses in a sentence. It’s raining cats and dogs. (connects words) That is not the norm, in times of peace or in times of turmoil. (connects phrases) I did not mean to insult you but it seems I did. (connects clauses). Kinds of Conjunctions 1. Coordinate or Coordinating Conjunctions – are conjunctions that connect words, phrases, or clauses of equal rank. The following are the coordinate conjunctions, arranged in an acronym that makes them easier to understand. F - for A - and N - nor B - but O - or Y - yet S - so Be careful of the words then and now; neither is a coordinating conjunction, so what we say about coordinating conjunctions' roles in a sentence and punctuation does not apply to those two words. Rules on Punctuation 1. When a coordinating conjunction connects two independent clauses, it is often (but not always) accompanied by a comma: Jungkook wants to play for UConn, but he has had trouble meeting the academic requirements. 2. When the two independent clauses connected by a coordinating conjunction are nicely balanced or brief, many writers will omit the comma: Jungkook has a great jump shot but he isn't quick on his feet. 3. The comma is always correct when used to separate two independent clauses connected by a coordinating conjunction. A comma is also correct when and is used to attach the last item of a serial list, although many writers (especially in newspapers) will omit that final comma: Jungkook spent his summer studying basic math, writing, and reading comprehension. 4. When a coordinating conjunction is used to connect all the elements in a series, a comma is not used: Presbyterians and Methodists and Baptists are the prevalent Protestant congregations in Oklahoma. 5. A comma is also used with but when expressing a contrast: This is a useful rule, but difficult to remember. 6. In most of their other roles as joiners (other than joining independent clauses, that is), coordinating conjunctions can join two sentence elements without the help of a comma. Hemingway and Fitzgerald are among the American expatriates of the between-the-wars era. Hemingway was renowned for his clear style and his insights into American notions of male identity. It is hard to say whether Hemingway or Fitzgerald is the more interesting cultural icon of his day. Although Hemingway is sometimes disparaged for his unpleasant portrayal of women and for his glorification of machismo, we nonetheless find some sympathetic, even heroic, female figures in his novels and short stories. Beginning a Sentence with “And” and “But” A frequently asked question about conjunctions is whether and or but can be used at the beginning of a sentence. This is what R.W. Burchfield has to say about this use of and: There is a persistent belief that it is improper to begin a sentence with And, but this prohibition has been cheerfully ignored by standard authors from Anglo-Saxon times onwards. An initial And is a useful aid to writers as the narrative continues. The same is true with the conjunction but. A sentence beginning with and or but will tend to draw attention to itself and its transitional function. Writers should examine such sentences with two questions in mind: (1) would the sentence and paragraph function just as well without the initial conjunction? (2) should the sentence in question be connected to the previous sentence? If the initial conjunction still seems appropriate, use it. The Usual Meanings of the FANBOYS The coordinate conjunctions can mean many things. The following outline their most common meanings. AND To suggest that one idea is chronologically sequential to another: "Jasmine sent in her applications and waited by the phone for a response." To suggest that one idea is the result of another: "Willie heard the weather report and promptly boarded up his house." To suggest that one idea is in contrast to another (frequently replaced by but in this usage): "Juanita is brilliant and Shalimar has a pleasant personality. To suggest an element of surprise (sometimes replaced by yet in this usage): "Hartford is a rich city and suffers from many symptoms of urban blight." To suggest that one clause is dependent upon another, conditionally (usually the first clause is an imperative): "Use your credit cards frequently and you'll soon find yourself deep in debt." To suggest a kind of "comment" on the first clause: "Charlie became addicted to gambling — and that surprised no one who knew him." BUT To suggest a contrast that is unexpected in light of the first clause: "Joey lost a fortune in the stock market, but he still seems able to live quite comfortably." To suggest in an affirmative sense what the first part of the sentence implied in a negative way (sometimes replaced by on the contrary): "The club never invested foolishly, but used the services of a sage investment counselor." To connect two ideas with the meaning of "with the exception of" (and then the second word takes over as subject): "Everybody but Jimmy is trying out for the team." OR To suggest that only one possibility can be realized, excluding one or the other: "You can study hard for this exam or you can fail." To suggest the inclusive combination of alternatives: "We can broil chicken on the grill tonight, or we can just eat leftovers. To suggest a refinement of the first clause: "Smith College is the premier all-women's college in the country, or so it seems to most Smith College alumnae." To suggest a restatement or "correction" of the first part of the sentence: "There are no rattlesnakes in this canyon, or so our guide tells us." To suggest a negative condition: "The New Hampshire state motto is the rather grim "Live free or die." To suggest a negative alternative without the use of an imperative (see use of and above): "They must approve his political style or they wouldn't keep electing him mayor." NOR The conjunction NOR is not extinct, but it is not used nearly as often as the other conjunctions, so it might feel a bit odd when nor does come up in conversation or writing. Its most common use is as the little brother in the correlative pair, neither-nor: He is neither sane nor brilliant. That is neither what I said nor what I meant. It can be used with other negative expressions: That is not what I meant to say, nor should you interpret my statement as an admission of guilt. It is possible to use nor without a preceding negative element, but it is unusual and, to an extent, rather stuffy: George's handshake is as good as any written contract, nor has he ever proven untrustworthy. YET The word YET functions sometimes as an adverb and has several meanings: in addition ("yet another cause of trouble" or "a simple yet noble woman"), even ("yet more expensive"), still ("he is yet a novice"), eventually ("they may yet win"), and so soon as now ("he's not here yet"). It also functions as a coordinating conjunction meaning something like "nevertheless" or "but." The word yet seems to carry an element of distinctiveness that but can seldom register. John plays basketball well, yet his favorite sport is badminton. The visitors complained loudly about the heat, yet they continued to play golf every day. In sentences such as the second one, above, the pronoun subject of the second clause ("they," in this case) is often left out. When that happens, the comma preceding the conjunction might also disappear: "The visitors complained loudly yet continued to play golf every day." Yet is sometimes combined with other conjunctions, but or and. It would not be unusual to see and yet in sentences like the ones above. This usage is acceptable. FOR The word FOR is most often used as a preposition, of course, but it does serve, on rare occasions, as a coordinating conjunction. Some people regard the conjunction for as rather highfalutin and literary, and it does tend to add a bit of weightiness to the text. Beginning a sentence with the conjunction "for" is probably not a good idea, except when you're singing "For he's a jolly good fellow. "For" has serious sequential implications and in its use the order of thoughts is more important than it is, say, with because or since. Its function is to introduce the reason for the preceding clause: John thought he had a good chance to get the job, for his father was on the company's board of trustees. Most of the visitors were happy just sitting around in the shade, for it had been a long, dusty journey on the train. SO Be careful of the conjunction SO. Sometimes it can connect two independent clauses along with a comma, but sometimes it can't. For instance, in this sentence, Soto is not the only Olympic athlete in his family, so are his brother, sister, and his Uncle Chet. where the word so means "as well" or "in addition," most careful writers would use a semicolon between the two independent clauses. In the following sentence, where so is acting like a minor-league "therefore," the conjunction and the comma are adequate to the task: Soto has always been nervous in large gatherings, so it is no surprise that he avoids crowds of his adoring fans. Sometimes, at the beginning of a sentence, so will act as a kind of summing up device or transition, and when it does, it is often set off from the rest of the sentence with a comma: So, the sheriff peremptorily removed the child from the custody of his parents. 2. Correlative Conjunctions Correlative Conjunctions are coordinate conjunctions used in pairs. The most commonly used correlative conjunctions are: both . . . and neither . . . nor not only . . . but also whether . . . or not . . . but as . . . as either . . . or 3. Subordinate Conjunctions A subordinate conjunction is a conjunction that connects clauses of unequal rank. It connects a subordinate clause to a principal or an independent clause. A subordinate clause is one that depends upon some other part of a sentence. Following is a list of the most common subordinate conjunctions: after even if since when although even though so that whenever as if than where as if if only that whereas as long as in order that though wherever as though now that till while because once unless before rather than until The conjunctive adverbs—the words that do the work of an adverb and a conjunction—such as however, moreover, nevertheless, consequently, as a result are used to create complex relationships between ideas and are likewise considered as subordinate conjunctions. The Case of Like and As Strictly speaking, the word like is a preposition, not a conjunction. It can, therefore, be used to introduce a prepositional phrase ("My brother is tall like my father"), but it should not be used to introduce a clause ("My brother can't play the piano like as he did before the accident" or "It looks like as if basketball is quickly overtaking baseball as America's national sport."). To introduce a clause, it's a good idea to use as, as though, or as if, instead. Like As I told you earlier, the lecture has been postponed. It looks like as if it's going to snow this afternoon. Jungkook kept looking out the window like as though he had someone waiting for him. In formal, academic text, it's a good idea to reserve the use of like for situations in which similarities are being pointed out: This community college is like a two-year liberal arts college. However, when you are listing things that have similarities, such as is probably more suitable: The college has several highly regarded neighbors, like such as the Mark Twain House, St. Francis Hospital, the Connecticut Historical Society, and the UConn Law School. Omitting That The word that is used as a conjunction to connect a subordinate clause to a preceding verb. In this construction that is sometimes called the "expletive that." Indeed, the word is often omitted to good effect, but the very fact of easy omission causes some editors to take out the red pen and strike out the conjunction that wherever it appears. In the following sentences, we can happily omit the that (or keep it, depending on how the sentence sounds to us): Isabel knew [that] she was about to be fired. She definitely felt [that] her fellow employees hadn't supported her. I hope [that] she doesn't blame me. Sometimes omitting the that creates a break in the flow of a sentence, a break that can be adequately bridged with the use of a comma: The problem is, that production in her department has dropped. Remember, that we didn't have these problems before she started working here. As a general rule, if the sentence feels just as good without the that, if no ambiguity results from its omission, if the sentence is more efficient or elegant without it, then we can safely omit the that. Theodore Bernstein lists three conditions in which we should maintain the conjunction that: When a time element intervenes between the verb and the clause: "The boss said yesterday that production in this department was down fifty percent." (Notice the position of "yesterday.") When the verb of the clause is long delayed: "Our annual report revealed that some losses sustained by this department in the third quarter of last year were worse than previously thought." (Notice the distance between the subject "losses" and its verb, "were.") When a second that can clear up who said or did what: "The CEO said that Isabel's department was slacking off and that production dropped precipitously in the fourth quarter." (Did the CEO say that production dropped or was the drop a result of what he said about Isabel's department? The second that makes the sentence clear.) Beginning a Sentence with Because Somehow, the notion that one should not begin a sentence with the subordinating conjunction because retains a mysterious grip on people's sense of writing proprieties. This might come about because a sentence that begins with because could well end up a fragment if one is not careful to follow up the "because clause" with an independent clause. Because e-mail now plays such a huge role in our communications industry. When the "because clause" is properly subordinated to another idea (regardless of the position of the clause in the sentence), there is absolutely nothing wrong with it: Because e-mail now plays such a huge role in our communications industry, the postal service would very much like to see it taxed in some manner. 4. Other Connectives Although the work of conjunctions is to connect, this does not mean that all connectives are conjunctions. Relative adverbs and relative pronouns are also used to connect clauses of unequal rank. Since it is raining, the picnic will be postponed. Wednesday is the day when we shall have the picnic. (Relative Adverb) We shall have our picnic in the grove that adjoins the school grounds. (Relative pronoun) The Correct use of Conjunctions 1. “Than” and “As” The conjunctions “than” and “as” are used to compare one thing with another, and there is usually an omission of words after each. The substantive word which follows “than” or “as” must be in the same case as the word with which it is compared. Particular care must be taken when the substantive is a personal pronoun. She is smaller than I am small. I am as small as she is small. 2. “Unless” and “Without” “Unless” is a conjunction and introduces a clause. “Without” is a preposition and introduces a “phrase”. We are going on as planned unless it rains. We would go without umbrellas and hats. 3. “Like”, “As”, and “As If” “As” and “As if” are conjunctions and are used to introduce clauses. “Like” is a preposition and is used to introduce a phrase. He talks as a child talks. (Clause) He talks as if he’s running out of words. (Clause) He talks like a chipmunk. (Phrase) INTERJECTIONS Interjections are words or phrases used to exclaim or protest or command. They express some strong or sudden emotion. They sometimes stand by themselves, but they are often contained within larger structures. Look! There’s a bird. Wait! I don’t understand Wow! I won the lottery! Oh, I don't know about that. I don't know what the heck you're talking about. No, you shouldn't have done that. An interjection is grammatically distinct from the rest of the sentence. They may express delight, disgust, contempt, pain, assent, joy, impatience, surprise, sorrow, and so forth. They are generally set off from the rest of the sentence by exclamation points. An entire sentence, however, may be exclamatory. If the sentence is exclamatory, the interjection is followed by a comma and the exclamation point is placed at the end of the sentence. Following is a list of the most common interjections: Ah! Hark! Listen! Sh! Alas! Hello! Lo! What! Beware! Hurrah! Oh! Good! Bravo! Hush! Ouch! Indeed! The Proper Use of “O” and “Oh” The interjection “O” is used only before a noun in direct address. It is not directly followed by an exclamation point. “Oh” is used to express surprise, sorrow, or joy. It is followed by an exclamation point unless the emotion continues throughout the sentence. O God! Help me please! Oh, I love you! Oh! She is here. SYNTAX AND MECHANICS POINTERS I. PHRASES A phrase is a group of related words used as a single part of speech. They mainly add variety to and relieve monotony of sentences. Look at the following sentences: Vietnamese scarves are all the rage this season. Scarves from Vietnam are all the rage this season. I sadly looked at her. I looked at her with sadness. Note that the subsequent sentences mean the same thing. Only in the first sentence, a single word is used to modify the noun scarves whereas in the second one, a group of words modify scarves. Likewise in the third sentence, one word – sadly – modify the verb looked whereas in the second one, a group of words – with sadness – modifies the same verb looked. KINDS OF PHRASES Divisions according to Form Phrases may be introduced by prepositions, participles, or infinitives. The introductory word determines the classification of the phrase according to form. A prepositional phrase is a phrase introduced by a preposition. A participial phrase is a phrase introduced by a participle. An infinitive phrase is a phrase introduced by an infinitive. Examples: I am leaving in an hour. (prepositional phrase) The boy wearing the baseball cap is our school’s team captain. (participial phrase) To be free is all I ask for. (infinitive phrase) Divisions according to Use Phrases may be used as adjectives, as adverbs, or as nouns. The function determines the classification of a phrase according to use. An adjectival phrase is a phrase used as an adjective. An adverbial phrase is a phrase used as an adverb. A noun phrase is a phrase used as a noun. Examples: A group of students went past. (adjectival phrase) I motioned to her to her with sweeping gestures. (adverbial phrase) She liked being admired. (noun phrase) II. CLAUSES A clause is a part of the sentence containing, in itself, a subject and a predicate. KINDS OF CLAUSES Independent Clause Clauses that make independent statements are called independent or coordinate clauses. The independent clause forms a complete sentence by itself. They are also referred to as principal clauses when used with subordinate clauses. Subordinate Clause Clauses that depend upon some other part of the sentence are dependent or subordinate clauses. The subordinate clause is therefore not complete without the principal clause. Examples: It was he who helped me get my confidence back. IC SC It is imperative that you keep your promise. IC SC TYPES OF SUBORDINATE CLAUSES Subordinate clauses may be used as adjectives, adverbs, or nouns; and as such are known as adjectival, adverbial, or noun clauses. Adjectival Clause An adjective clause is a subordinate clause used as an adjective. Adjectival clauses are usually introduced by relative pronouns (e.g. who, which, what, and that) or relative adverbs (e.g. when, where, and why). The girl who is wearing the red obi topped the UPCAT last year. A restrictive clause is a clause that helps point out, or identifies a certain person or object, and is a necessary part of the sentence. He who has loved much is much loved as well. A nonrestrictive clause is a clause that merely adds to the information given in the principal clause and is not necessary to the sense of the sentence. He, who has loved much, is much loved as well. Adverbial Clause An adverbial clause is a subordinate clause used as an adverb. Remember that adverbial clauses, just like adverbs, may modify a verb, an adverb, or an adjective. Adverbial clauses are usually introduced by conjunctive adverbs (e.g. after, until, as, when, before, where, since, and while) or subordinate conjunctions (e.g. as, that, since, because, then, so, for, than, though, if, provided, and unless). Gregory was on his way home when the bullies assaulted him. Note on punctuation: Every introductory adverbial clause may be separated by a comma. In certain adverbial clauses, a comma is necessary to make a meaning clear. When you arrive, please get the mail. (may or may not use a comma) After he ate too quickly, his stomach ached. (comma is necessary; without the comma the reader will be confused about which quickly modifies: ate or ached) Noun Clauses A noun clause is a subordinate clause used as a noun. That it boggles the mind is inevitable. A sentence that has a noun clause is a complex sentence. The entire sentence is considered the principal or independent clause; the noun clause is the subordinate clause. That it boggles the mind is inevitable. (Principal clause) That it boggles the mind. (Subordinate clause) Uses of Noun Clauses A noun clause has the same uses as nouns. It may be used as subject of a verb, object of a verb, the predicate nominative, the object of a preposition, or in apposition. Noun clause used as Subject A noun clause may be used as the person, place or thing about which a statement is being made. That you may see the error of your ways is my fervent wish. Noun clause used as Direct Object A transitive verb passes the action from a doer to a receiver. In the active voice, the doer is the subject and the receiver is the object. I doubt that you can do it. Noun clause used as Predicate Nominative The predicate nominative follows a linking verb and completes its meaning. In the following example, is is a linking verb and the underlined phrase completes the action by the verb; explains My wish. My wish is that you may see the error of your ways. Noun clause used as Object of Preposition A preposition shows the relationship between its object and some other word in the sentence. Instead of using a noun in this case, we use a noun clause as the object being related to some other word in the sentence. I was thinking about all that we have accomplished. Noun clause used in Apposition An appositive is a word or a group of words that follows a noun or a pronoun and gives additional information about this noun/pronoun. In the following examples, the noun clause in both sentences is used as appositives. My wish, that you may see the error of your ways, is heartfelt. It is my wish that you may see the error of your ways. Caution: Do not confuse an appositive clause with an adjectival clause introduced by that. When that introduces an adjectival clause, it is a relative pronoun. When that introduces a noun clause, it is a conjunction. III. SENTENCES A sentence is a group of words expressing a complete thought. I did not like her at first. I began to see how she truly was. I started to like her. ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF A SENTENCE Every sentence has a subject and a predicate. The subject may or may not be expressed but the predicate is always expressed. The Subject – is a part of the sentence which names a person, a place or a thing about which a statement is made. This is, in a nutshell, what is being discussed or spoken about in the sentence. The subject with all its modifiers is called the complete subject. Children are gifts. Good and behaved children are gifts from God. Come here. (subject not expressed) The Predicate – is that part of the sentence which tells us something about the subject. The predicate with all its modifiers and complements is called the complete predicate. Children are gifts. Good and behaved children are gifts from God. NATURAL AND TRANSPOSED ORDER IN SENTENCES Natural Order Whenever the complete predicate follows the complete subject, a sentence is in the natural order. To be forgiven is such a sweet and liberating experience. Subject Predicate Transposed Order Whenever the complete predicate or part of the predicate is placed before the subject, a sentence is in the transposed order. Up flew the birds. Did you give her the book? Subject Predicate COMPOUND ELEMENTS OF A SENTENCE Compound Subject If the subject of the sentence consists of more than one noun or pronoun, it is said to be a compound subject. God’s grace and love are necessary to us. Compound Predicate If the predicate consists of more than one verb, it is said to be a compound predicate. You were weighed, measured and found wanting. CLASSIFICATION OF SENTENCES Division according to Use A declarative sentence is a sentence that states a fact. An interrogative sentence is a sentence that asks a question. An imperative sentence is a sentence that expresses a command. An exclamatory sentence is a sentence that expresses sudden or strong emotion. Examples: The bus driver was tired from working all day. (declarative) Will I be needed further? (interrogative) Get here as quick as you can. (imperative) Oh, how I was looking forward to meeting you! (exclamatory) Notes on punctuation: Declarative and imperative sentences are followed by periods. An interrogative sentence ends with a question mark. An exclamatory sentence ends with an exclamation point. Division according to Form A simple sentence is a sentence containing one subject and one predicate, either or both of which, may be compound. Mary and Joseph sheltered under a goat shed. A compound sentence is a sentence that contains two or more independent clauses. Mary and Joseph sheltered under a goat shed, and they stayed there until Jesus was born. Notes on punctuation of compound sentences: 1. The clauses of a compound sentence connected by the simple conjunctions and, but, and or are generally separated by a comma. She was very late for her first class, but her teacher understood her reasons and let her in still. 2. If the clauses are short and closely related, the comma may be omitted. The protesters surged toward the palace and the policemen were helpless. 3. Sometimes, the clauses of a compound sentence have no connecting word. The connection is then indicated by a semicolon. Stephanie and Peter were married immediately; it was what they both wanted. 4. The semicolon is also used to separate the clauses of a compound sentence connected by nevertheless, moreover, therefore, however, thus, then because these words have very little connective force. A comma is frequently used after these words. The doctor quickly performed emergency procedures as soon as he arrived at the scene of the accident; however, he was too late to save the victim. A complex sentence is a sentence that contains one principal clause and one or more subordinate clauses. The books, which were ordered last week, are finally arriving today. IV. PUNCTUATION Punctuations help make the meaning of written statements clear. THE PERIOD Use a period: 1. At the end of a declarative statement or an imperative sentence. 2. After an abbreviation or initial. Dr. Mandy T. Gregory THE COMMA Use a comma: 1. To separate words or group of words in a series. Please choose between coffee, tea, lemonade, or fruit juice. 2. To set off a short direct quotation and the parts of a divided quotation, unless a question mark or an exclamation point is required. “Please choose between coffee, tea, lemonade or fruit juice,” offered the stewardess. “I hope they’ll be comfortable,” prayed the host, “and may long they like staying here.” 3. To separate independent elements and words of direct address. Yes, I think so. Mother, I am sick. 4. To set off the parts of dates, addresses, or geographical names. June 15, 2005 5. To separate nonrestrictive phrases and clauses from the rest of the sentence. The youth, who are supposedly the hope of the motherland, couldn’t care less. 6. After long introductory phrases and clauses and when needed to make meaning clear. While you were waiting at the airport entrance, I was waiting at the tarmac. 7. To set off an appositive that is not part of the name or that is not restrictive. It is my wish, that you may see the error of your ways. 8. To set off a parenthetical expression; that is, a word or a group of words inserted in the sentence as a comment or an exclamatory remark, and one that is not necessary to the thought of the sentence. The nurses, as well as the doctor, are confident about the patient’s full recovery. 9. To separate the clauses of a compound sentence connected by the conjunctions and, but, or, nor, yet. If the clauses are short and closely related, the comma may be omitted. I honored my word, but you didn’t honor yours. 10. After the salutation in a social letter and after the complimentary close in all letters. Dear Don, Yours truly, THE SEMICOLON Use a semicolon: 1. To separate the clauses of a compound sentence when they are not separated by a coordinate conjunction. I honored my word; you didn’t honor yours. 2. To separate the clauses of a compound sentence, which are connected by nevertheless, moreover, however, therefore, then, or thus, since these words have very little connective force. She got consistently good grades; thus, she graduates cum laude today. 3. Before as and namely when these words introduce an example or an illustration. I have been to the most romantic city in Europe; namely, Paris. THE COLON Use a colon: 1. After the salutation of a business letter. Dear Sir: 2. Before a list or enumeration of items. Here is a list of government agencies: DOLE, DTI… 3. Before a long direct quotation. John Locke in his Second Treatise of Government said: "The State of Nature has a Law of Nature to govern it, which obliges everyone : And Reason, which is that Law, teaches all Mankind who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his Life, Health, Liberty, or Possessions." THE EXCLAMATION POINT Use an exclamation point: 1. After an exclamatory sentence. I can’ t believe it! You’re really here! 2. After an exclamatory word, phrase , or clause. Wow! What a game! That was great! THE QUESTION MARK Use a question mark: 1. At the end of every question. Are there any questions? QUOTATION MARKS Use quotation marks: 1. Before and after every direct quotation and every part of a divided quotation. For quotations within a quotation, use single quotation marks. “Locke has described the State of Nature much as Hobbes had, but then he adds ‘something different,’ or so Montague believes,” said the professor. 2. To enclose titles of stories, poems, magazines, newspaper articles, and works of art. The usual practice for titles of books, magazines and newspapers is italicization. “Ode to my Family” 3. Periods and commas belong inside quotations. Colons and semicolons are written after quotation marks. Gloria said, “I didn’t reckon on your being here so early in the morning.” “I didn’t know you were coming,” Gloria remarked. THE APOSTROPHE Use an apostrophe: 1. To show possession. My sister’s shoes are hard to fill. 2. With s to show the plural of letters, numbers, and signs. How many a’s are there in this sentence? 3. To show the omission of a letter, letters or numbers. The 25th of February in ’95 We’ll THE HYPHEN Use a hyphen: 1. To divide a word at the end of a line wherever one or more syllables are carried to the next line. 2. In compound numbers from twenty-one to ninety-nine. I have thirty-three baskets already. 3. To separate the parts of some compound words. My brother-in-law and my father-in-law are coming to visit tomorrow morning. THE DASH Use a dash: 1. To indicate a sudden change of thought. He is still at the school—an unusual thing for him. CAPITAL LETTERS Capitalize the first letter of the following: 1. The first word in a sentence. 2. The first word of every line of poetry (not very strict due to poetic license). 3. The first word of a direct quotation. 4. Proper nouns and proper adjectives. 5. Titles of honor and respect when preceding the name. 6. North, south, east, and west when they refer to sections of a country. 7. All names referring to God, the Bible, or parts of the Bible. 8. The principal words in the titles of books, plays, poems and pictures. 9. The pronoun I and the interjection O. 10. Abbreviations when capitals would be used if the words were written in full. Do not capitalize: 1. The seasons of the year. 2. The articles a, an, the, conjunctions, or prepositions in titles, unless one of these is the first word. 3. The names of subjects, unless they are derived from proper nouns. 4. The words high school, college, and university, unless they are parts of the names of particular institutions. 5. Abbreviations for the time of day. (a.m./p.m.) V. BADLY CONSTRUCTED SENTENCES The following are common mistakes in sentence construction: SENTENCE FRAGMENTS It is a basic rule in grammar that every sentence must contain at least one independent clause. A misplaced period may cut off a piece of the sentence, thereby resulting in a sentence that does not contain an independent clause. In the following example, the second sentence is a fragment due to a misplaced period. The committee met early to discuss the barangay budget allocation. Which is a complicated matter. Common Types of Sentence Fragments Fragment appositive phrase A major social problem is the number of undesirable people coming into the state. Professional gamblers and crooks, men who would do anything to make money. Corrected: A major social problem is the number of undesirable people coming into the state— professional gamblers and crooks, men who would do anything to make money. Fragment prepositional phrase I had expected to find the laboratory neat and orderly, but actually it was very sloppy. With instruments on every available space and pieces of electronic equipment lying around the floor. Corrected: I had expected to find the laboratory neat and orderly, but actually it was very sloppy. Instruments were on every available space and pieces of electronic equipment were lying around the floor. Fragment dependent clause A group of ants is busy looking for food and ferrying them back and forth. While another group of ants was busy protecting the colony. Corrected: A group of ants is busy looking for food and ferrying them back and forth, while another group of ants was busy protecting the colony. Fragment participial phrase I was amazed at how alive the city was. Everywhere there were vendors, hawking their unique and varied wares. Calling the attention of shoppers and nudging them in the hope that they’ll be attracted enough to buy. Corrected: I was amazed at how alive the city was. Everywhere there were vendors hawking their unique and varied wares, calling the attention of shoppers, and nudging them in the hope that they’ll be attracted enough to buy. Fragment Infinitive Phrase To get rich the best way how. That is the aim of every businessman I have met, and I doubt if I’ll meet one with a different goal. Corrected: To get rich the best way how is the aim of every businessman I have met, and I doubt if I’ll meet one with a different goal. Permissible Incomplete Sentences Certain elliptical expressions stand as sentences because their meanings are readily understood, especially in a conversation context. 1. Questions and answers to questions especially in conversations. Why not? Because it’s late. 2. Exclamations and requests Yes! This way, please. 3. Transitions So much for that. Now to go to the other issue. There’s also the case of descriptive or narrative prose where fragments are deliberately used for effect. The clock ticked and tocked. Tick and tock. Tick and tock. RUN-TOGETHER SENTENCES This error is also known as the comma splice. This mistake is produced by a misplaced comma. Particularly, it is the use of a comma to connect two independent clauses not conjoined by coordinating conjunctions. Give me liberty, give me death. Three Ways of Correcting Run-Together Sentences Use a semicolon between the two independent clauses Give me liberty; give me death. Use a period between the clauses and make them two sentences instead. Give me liberty. Give me death. Insert a coordinating conjunction between the two clauses Give me liberty or give me death. VI. COMMON MISTAKES IN SENTENCE CONSTRUCTION SENTENCE UNITY A sentence is unified if the various ideas it contains all contribute to making one total statement and if the unifying idea, which ties the various parts together, is made clear to the reader. Faults in sentence unity include inclusion of irrelevant ideas, excessive detail, illogical coordination and faulty subordination. Irrelevant Ideas These are ideas that do not help and contribute to the sentence. Totchelyn got into a fight and when a person gets into a fight, he or she is probably going to be agitated after and this does not contribute to overall feeling of well-being. Problem: Who or what is the topic of the sentence, Totchelyn or well-being? Problematic Statements: A student, whether he or she goes to the University of the Philippines, a premier university in the country which is patterned after Harvard which is a premier college abroad, or any other college or university in the land, should be thankful for the educational opportunity. Improved: A student, whether he or she goes to a premier university like the University of the Philippines or to any other college or university, should be thankful for the educational opportunity. Meeting you has made all the difference for I have never loved nor will love any other man than you, and love means not having to say you’re sorry. Problem: This sentence is about expressing the speaker’s joy in finding her true love. The definition of love in the end is very irrelevant. Leave it out or make it another sentence. Seeming lack of unity: Radio stars have to practice hard to develop pleasant speaking voices; it is very important that they acquire a sense of timing so programs will begin and end promptly. Improved: Radio stars have to practice hard to develop pleasant speaking voices and to improve their sense of timing so that programs will begin and end promptly. Faulty sentence break: Hobbes believed men are naturally equal. He believed they had the same liberties and rights, and moreover he thought men in that state are miserable. Improved: Hobbes believed men are naturally equal, that they had the same liberties and rights. Moreover, he thought men in that state are miserable. Excessive Detail If the sentence contains too many ideas, none of them will stand out and the sentence will seem overcrowded and pointless. Overcrowded sentence: When Rizal and the rest of the ilustrados agitated for equal rights for the Filipinos, other Filipinos heard and took these protests as reason to go up in the mountains and fight a guerilla war with the Spaniards where they lost most of the time yet proved that they would not sit back and let foreigners take over their own country. Improved: When Rizal and the rest of the ilustrados agitated for equal rights for Filipinos, other Filipinos heard. These Filipinos took the ilustrados’ protests as a reason to go up in the mountains and fight a guerilla war with the Spaniards. They lost most of the time, indeed, but they proved that they would not sit back and let foreigners take over their own country. Just because two ideas are related, and thus naturally follow each other; that doesn’t mean they belong to one sentence. Lack of sentence unity: I will give you a grand tour of the campus after I got my things unloaded at the desk and I hope you will enjoy it here. Improved: I will give you a grand tour of the campus after I got my things unloaded at the desk. I hope you will enjoy it here. SUBORDINATION To make main points stand out clearly, less important points must be made less conspicuous. Main ideas should be expressed in independent clauses, which are the backbone of any sentence. Minor descriptive details, qualifications, and incidental remarks should be put into subordinate constructions—dependent clauses, appositives, or modifying phrases. Primer sentences A series of short independent sentences may produce the jerky primer style of elementary students. A disadvantage of such writing is that there seems to be no sentence that is more important than the rest. Primer sentences should be unified into longer sentences, with less important ideas subordinated. Primer Sentences: 1. Look at how she dances. She shows harmony and grace. She is dancing to a jazz piece. She is beautiful to watch. 2. I gave everything to that cause. I gave all my strength. I gave all my time. I gave all my interest. Look where it brought me. Improved Sentences: 1. Look at how she dances to the jazz piece, showing such harmony and grace and is such a beauty to watch. 2. I gave everything—my strength, my time, and my interest— to that cause, but look where it brought me. Illogical Coordination When sentence elements are joined by and or another coordinating conjunction, the implication is that the elements are of equal weight and importance. If that is not really the case, one of them should be subordinated. Illogically coordinated sentences: 1. A large sugar plant was built allegedly to supply the whole country with its sugar needs and is now operational. 2. You should get and shred a piece of ribbon and a size no greater than 0.5 centimeters. 3. I got a free afternoon, and I thought about what I’d like to do, and I decided to clean the house, but my friend Sheila arrived, and we went to the mall instead. Improved Sentences: 1. A large sugar plant, built allegedly to supply the whole country with its sugar needs, is now operational. 2. You should get and shred a piece or ribbon to a size no greater than 0.5 centimeters. 3. When I got a free afternoon, I thought about what I’d like to do and decided to clean the house. However, my friend Shiela arrived so she and I went to the mall instead. Faulty Subordination When the main idea of the sentence is placed in a subordinate construction, the resulting upside-down subordination makes the sentence weak. The context, of course, determines which ideas are relatively more, and which are relatively less important. Faulty Subordination: 1. I was mooning around when my classmate called my name which caused me to trip. 2. The movie had an opening scene which people thought was irrelevant and unnecessarily gory. Improved sentences: 1. While I was mooning around, my classmate called my name and caused me to trip. 2. People thought the opening scene of the movie was irrelevant and unnecessarily gory. PARALLELISM Parallel thoughts should be expressed in parallel grammatical form. For example, an infinitive should be paralleled by an infinitive, not by a participle; a subordinate clause by another subordinate clause, not by a phrase. Parallel method is one way of showing readers the relation between your ideas. Coordinate Constructions The coordinating conjunctions (like and, or, but, and nor) are sure signs of compound construction. Any sentence element which can be joined by a coordinating conjunction should be parallel in construction. Sentences that are not parallel: 1. Among the responsibilities of a UP student are studying hard and to serve the country. 2. I would like to discuss and focusing on the issues at hand. 3. Every child is taught to work with the team and that good sportsmanship must be shown. Sentences that are parallel: 1. Among the responsibilities of a UP student are studying hard and serving the country. 2. I would like to discuss and focus on the issues at hand. 3. Every child is taught to work with the team and to show good sportsmanship. Elements in Series Sentence elements in series (x, y, and z) should express parallel ideas and be parallel in grammatical form. Faulty Parallelism: 1. She is young, well educated, and has an aggressive manner. 2. I was weighed, has been measured, and was found wanting. 3. He was tall, dark, and wore a black coat. Improved Parallelism: 1. She is young, well educated, and aggressive. 2. I was weighed, measured, and found wanting. 3. He was tall, dark, and black-coated. (Or, “He was tall and dark, and he wore a black coat.”) Repetition of Prepositions and Other Introductory Words: In order to make a parallelism clear, it is often necessary to repeat a preposition, an article, a relative pronoun, a subordinating conjunction, an auxiliary verb, or the sign of the infinitive. Obscure Parallelisms: 1. The lady must decide who among the suitors she likes best and not waste time informing them of her decision. 2. The cashier told him that his account has not been cleared yet and he must do so first before he can claim benefits. 3. The area was littered by plastic bottles and candy wrappers, and the tourists who produced all the garbage. Clear Parallelism: 1. The lady must decide who among the suitors she likes best and must not waste time informing them of her decision. 2. The cashier told him that his account has not been cleared yet and that he must do so first before he can claim benefits. 3. The area was littered by plastic bottles and candy wrappers, and by tourists who produced all the garbage. Note: It is not necessary to repeat the connective word when the parallel elements are short and stand close together. Correlatives Correlative conjunctions like either…or, neither…nor, not only…but also should be followed by parallel sentence elements. Undesirables: 1. He is not only discourteous to the students but also to the teacher. (Not only is followed by an adjective with a prepositional phrase modifying it; but also is followed by a prepositional phrase.) 2. He either was a magnificent liar or a remarkably naïve young man. (Either is followed by a verb and its noun complement; or is followed by a noun and its modifying adjectives. Improved: 1. He is discourteous not only to the students but also to the teacher. (The correlatives are each followed by a prepositional phrase now) 2. He was either a magnificent liar or a remarkably naïve young man. (Each correlative is followed by a noun complement of the verb) And Which Clauses Avoid joining a relative clause to its principal clause by and or but. An undesirable and which construction can be corrected three ways: 1. by omitting the coordinating conjunction, 2. changing the relative clause to a principal clause, or 3. inserting a relative clause before the conjunction. Undesirables: 1. We were fooling around on our way to the canteen when we were shushed by the Dean and who had a disagreeable disposition. 2. The witness appeared at the hearing with a long written statement, but which he was not allowed to read. Improved: 1. We were fooling around on our way to the canteen when we were shushed by the Dean who had a disagreeable disposition. 2. We were fooling around on our way to the canteen when we met the Dean who had a disagreeable disposition and who shushed us. 3. The witness appeared at the hearing with a long written statement, but he was not allowed to read it. FAULTY REFERENCE OF PRONOUNS The antecedent of every pronoun should be immediately clear to the reader. Faulty reference of pronouns is particularly hard to detect in a first draft. Ambiguous Reference Do not use a pronoun in such away that it might refer to either of the two antecedents. Do not practice explaining the pronoun by repeating of antecedent in parentheses. Undesirable: 1. Dona met Michelle when she was on the way to school (To whom is she referring to, Dona or Michelle?) 2. Dona met Michelle when she (Michelle) was on the way to school. Improved: 1. Dona, on her way to school, met Michelle. Reference to Remote Antecedent A pronoun need not be in the same sentence as its antecedent, but the antecedent should not be so remote as to cause possible misreading. If a considerable amount of material stands between the antecedent and the pronoun, repeat the antecedent. Undesirable: Cindy lacked enough money to buy the beautiful dress that was made of silk, gorgeously cut, and very expensive. Dozens of other dresses were in the store as well but they were no competition to the dream dress that she wanted. Improved: …but they were no competition to the dream dress that Cindy wanted. Reference to Implied Antecedent Do not use a pronoun to refer to a noun which is not expressed but has to be inferred from another noun. Antecedent implied: I once knew a very old violinist who repaired them very expertly. Improved: I once knew an old violinist who repaired violins very expertly. Reference to Inconspicuous Antecedent Do not use a pronoun to refer to a noun in a subordinate construction where it may be overlooked by the reader. A noun that is used as an adjective is likely to be too inconspicuous to serve as an antecedent. Inconspicuous antecedent: Adobe brick was used in the wall, which is a Spanish word for sun-dried clay. Improved: The bricks in the wall were made of adobe, which is a Spanish word for sun-dried clay. Broad Reference Using a relative or demonstrative pronoun (which, that, this) to refer to the whole idea of a preceding clause, phrase or sentence is acceptable if the sense and if a change would be awkward and wordy. Acceptable broad reference: At first glance, the desert seems completely barren of animal life, but this is a delusion. Undesirable: The battle of Thermopylae was the battle where Spartans fought the Persians and where every Spartan who fought was killed, the account of which can be found in many books. Improved: The battle of Thermopylae was the battle where Spartans fought the Persians and where every Spartan who fought was killed. The account of this battle is told in many books. Ambiguous: The beginning of the book is more interesting than the conclusion, which is very unfortunate. Improved: Unfortunately, the beginning of the book is more interesting than the conclusion. Awkward: In the eighteenth century more and more land was converted into pasture, which had been going on to some extent for several centuries. Improved: In the eighteenth century, more and more land was converted into pasture, a process which had been going on to some extent for several years. Personal Pronouns Used Indefinitely Although the indefinite you is suitable in informal writing, it is generally out of place in formal compositions. Instead, use the impersonal pronoun one, or put the verb in the passive voice. Informal: You should not take sedatives without a doctor’s prescription. Formal: One should not take sedatives without a doctor’s prescription. Formal or Informal: Sedatives should not be taken without a doctor’s prescription. The indefinite use of they is always vague and usually sounds childish and naïve. Undesirable: Thirty years ago, there was no such thing as an atomic bomb; in fact, they did not even know how to split the atom. Improved: …in fact, scientists did not even know how to split the atom. The indefinite it is correctly used in impersonal expressions (e.g. it is raining, it is hot) or in sentences where it anticipates the real subject (e.g. It seems best to go at once) Colloquial use like “It says here that…” should not be used in writing. Undesirable: It says in the paper that they are having severe storms in the West. Improved: The paper says there are severe storms in the West. Demonstrative Pronouns and Adjectives The pronouns this, that these, those are frequently used as adjectives, to modify nouns. Using one of these words as a modifier, without an expressed or clearly implied antecedent, is a colloquialism which should be avoided in serious writing. Acceptable: After struggling through the poetry assignment, I decided that I would never read one of those poems again. Colloquial: It was just one of those things. Colloquial: The building was one of those rambling old mansions. Improved: The building was one of those rambling old mansions that are found in every New England town. DANGLING MODIFIERS A modifier is a dangling modifier when there is no word in the sentence for it to modify. In the sentence “Swimming out into the lake, the water felt cold,” the writer took it for granted that the reader would assume somebody was swimming. In fact, the only noun in the sentence is water and the participial phrase Swimming out into the lake could not logically be modifying it; the water could not be swimming. Thus, this participial phrase is a dangling modifier. A Dangling modifier can be remedied in two ways: 1. By supplying the noun or pronoun that the phrase logically modifies Swimming out into the cold, I felt that the water was cold. 2. By changing the dangling modifier into a complete clause (one which has a subject and predicate) As I swam out into the lake, the water felt colder. Dangling Participles, Gerunds and Infinitives Dangling participial phrase: Strolling around the park one day, a baby suddenly cried. (Who was strolling) Improved: As I was strolling around the park one day, a baby suddenly cried. Dangling Gerund Phrase: For opening the door to let her in, the beautiful lady gave me a radiant smile. (Who opened the door?) Improved: The beautiful lady gave me a radiant smile after I had opened the door for her. Dangling infinitive phrase: To pass the difficult entrance examination, all possible topics must be covered in the review. Improved: To pass the difficult entrance examination, a student must cover all possible topics in the review. Dangling Elliptical Clauses Subject and main verb are sometimes omitted from a dependent clause. These clauses are called elliptical clauses: Instead of while he was going, while going is used. Instead of when he was a boy, when a boy is used. If the subject of the elliptical clause is not mentioned in the rest of the sentence, it may become a dangling elliptical clause. Dangling: When six years old, my favorite pet dog died. Improved: When I was six years old, my favorite pet dog died. Permissible Introductory Expressions Some verbal phrases, like generally speaking, taking all things into consideration, judging from past experience have become stock introductory expressions and need not be attached to any particular noun. Similarly, verbals expressing a generalized process, like in swimming, in cooking, are often used without being attached to a particular noun. Acceptable: Generally speaking, males die younger than females. Taking all things into consideration, the decision was just and as it should be. Judging from past experience, UP graduates get hired much faster than others. In swimming, relaxation is essential. In cooking, the quality of the ingredients is important. MISPLACED SENTENCE ELEMENTS The normal sentence order in English is subject, verb, and complement, with modifiers either before or after the word being modified. This permits certain flexibility in the placing of subordinate clauses, but the following must be observed: 1. Place modifiers as close as possible to the words they modify 2. Do not needlessly split a grammatical construction by the insertion of another sentence element. Misplaced clauses and phrases Some subordinate clauses and modifying phrases can be moved around to various positions in the sentence without affecting its meaning. For example, an introductory adverbial clause can sometimes be shifted from the beginning to the middle or the end of the sentence. Whatever other people may say, I still believe that faith is a matter best left to the individual’s discretion. I still believe, whatever other people may say, that faith is a matter best left to the individual’s discretion. I still believe that faith is a matter best left to the individual’s discretion, whatever other people may say. This freedom, however, has its dangers. Modifiers may be placed so as to produce ridiculous misreading or real ambiguities. Split infinitives are a result of inserting a word or a group of words between the to and the verb form. This may be awkward, especially if the modifier is long. Misplaced modifier: Like many artists of the period, Carey lost the opportunity to make large profits on his paintings through the work of imitators and plagiarists. Corrected: Like many artists of the period, Carey lost, through the work of imitators and plagiarists, the opportunity to make large profits on his paintings. Awkward: I should like to, if the Lord blesses me with such grace, tour the world. Improved: I should like to tour the world, if the Lord blesses me with such grace. Misplaced Modifier: The ramp model wore a grey cardigan over one shoulder which looked fuzzy and warm. Corrected: The ramp model wore over one shoulder, a grey cardigan which looked fuzzy and warm. Acceptable: To never gain back my honor would be a great burden. Acceptable: The company is hoping to more than double its assets next year. Misplaced Adverbs Theoretically, limiting adverbs like only, almost, never, seldom, even, hardly, nearly should be placed immediately before the words they modify. Gino only tried to express his thanks. Gino and I fought only once. Formal: She gave you that food only to make up for yesterday’s fiasco. Informal: She only gave you that food to make up for yesterday’s fiasco. Acceptable: He seldom seems to smile. Acceptable: The migratory bird hardly appeared to be breathing. UNNECESSARY SHIFTS Structural consistency makes a sentence easier to read. If the first clause of a sentence is in the active voice, do not shift to the passive voice in the second clause unless there is some reason for the change. Similarly, avoid needless shifts in tense, mode, or person within a sentence. Shifts of Voice or Subject Shifting from the active to the passive voice almost always involves a change in subject; thus, an unnecessary shift in voice may make a sentence doubly awkward. Awkward: What would foreigners think of us if they only got their impression of the Philippines from Claire Danes’ maligning tongue? Improved: What would foreigners think of us if they got their impression of the Philippines only from Claire Danes’ maligning tongue? Ambiguous: I nearly ate all of it, leaving you with nothing. Improved: I ate nearly all of it, leaving you with nothing. Squinting Modifiers Avoid placing a modifier in such a position that it may refer to either a preceding or a following word. Ambiguous: The person who steals in nine cases out of ten is driven to do so by want. Improved: In nine cases out of ten, the person who steals is driven to do so by want. Ambiguous: Since a canoe cannot stand hard knocks when not in use it should be kept out of the water. Improved: Since a canoe cannot stand hard knocks, it should be kept out of the water when not in use. Awkward Split Constructions; Split Infinitives Any needless splitting of a grammatical construction by the insertion of a modifier may affect the meaning of the sentence. Awkward: The author made the horses, animals that we consider only fit for hard and brute labor, portray an ideal society. Improved: The author portrays an ideal society by means of horses, animals that we consider only fit for hard and brute labor. In some cases, infinitives are split by adverbs. This type of splitinfinitives is usually acceptable. Shift in subject and voice: When I finally found the trouble in an unsoldered wire, the dismantling of the motor was begun at once. Improved: When I finally found the trouble in an unsoldered wire, I began at once to dismantle the motor. Shift in voice: The new cellphone model is so innovative that it is wanted so badly by my friend. Improved: The new cellphone model is so innovative that my friend wants it so badly. Shift in subject: The children have played almost all the games there are, but games of hide and seek are their favorite. Improved: The children have played almost all the games there are, but they like hide and seek best. Shifts of Tense Do not change the tense unless there is reason to do so. Shift of tense: The family was usually quarreled over money matters, and when this new problem arises, the family is broken up. Improved: The family was usually quarreled over money matters, and when this new problem arose, the family was broken up. Shifts of Mode For example, If you begin a sentence with an imperative command (imperative mode), do not shift without reason to a statement (indicative mode). Shift of mode: Jump to the left; then you should jump to the right. (the first clause is a command, the second clause is a statement giving advice) Improved: Jump to the left; then jump to the right. Improved: After jumping to the left, you should jump to the right. Shift of mode: If I were you, I would be very grateful and I will thank him in any way I can. (Subjunctive, Indicative) Improved: If I were you, I would be very grateful and I would thank him in any way I can. Shifts of Person The most common shift in writing is from the third person to the second person. This usually happens when the writer is talking about no particular individual but of everyone in general. Needless shift: A man must always think happy thoughts for you can will happiness. Improved: You must always think happy thoughts for you can will happiness. Improved: A man must always think happy thoughts for he can will happiness. INCOMPLETE CONSTRUCTIONS Sentence constructions are incomplete if words and expressions necessary for clarity are omitted. Auxiliary Verbs Do not omit auxiliary verbs that are necessary to complete a grammatical construction. When the two parts of a compound construction are in different tenses, it is usually necessary to write the auxiliary verbs in full. Incomplete: Due to a vehicular accident last year, he can no longer walk and never walk again. Improved: Due to a vehicular accident last year, he can no longer walk and will never walk again. Idiomatic prepositions English idioms require that certain prepositions be used with certain adjectives: we say for example “interested in”, “aware of”, “devoted to”. Be sure to always include all necessary idiomatic prepositions. Incomplete: She is exceptionally interested and devoted to her friends. Improved: She is exceptionally interested in and devoted to her friends. Comparisons As and Than; One of the…if not the… In comparisons, do not omit words necessary to make a complete idiomatic statement. We say “as pretty as” and “prettier than”. Incomplete: Totchelyn is as pretty, if not prettier than Lolita. Complete but Awkward: Totchelyn is as pretty as, if not prettier than Lolita. Improved: Totchelyn is as pretty as Lolita, if not prettier. Incomplete: The September 11 bombing of the twin towers is one of the worst, if not the worst, terrorist attacks in the world. (two idioms: “one of the worst terrorist attacks” and the “worst terrorist attack”) Correct: The September 11 bombing of the twin towers is one of the worst terrorist attacks, if not the worst terrorist attack, in the world. Incomplete Comparisons Comparisons should be logical and unambiguous. Illogical: Her energy level is lower than an old lady. (Is an old lady low?) Improved: Her energy level is lower than that of an old lady. Improved: Her energy level is lower than an old lady’s. Avoid comparisons which are ambiguous or vague because they are incomplete. A comparison is ambiguous if it is too hard to tell what is being compared with what. It is vague if the standard of comparison is not stated. Ambiguous Comparison: Alabang is farther from Sucat than Makati. Clear: Alabang is farther from Sucat than Makati is. Vague comparison: The people have finally realized that it’s cheaper to commute. More Definite: The people have finally realized that it’s cheaper to commute than to drive. If it is clearly indicated by the context, the standard of comparison need not be specified. Acceptable: You are big, but I am bigger. MIXED CONSTRUCTIONS Do not begin a sentence with one construction and shift to another to conclude the sentence. English is full of alternate constructions and it is easy to confuse them. For example, here are two ways of saying the same thing: 1. Fishing in Alaska is superior to that of any other region in North America. 2. Alaska is superior to any other region in North America for lake and stream fishing. The first sentence compares fishing in two regions; the second compares two regions in regard to fishing. Either sentence is correct, but the combination of the first half of one with the second half of the other produces confusion. Mixed Construction: Fishing in Alaska is superior to that of any other region in North America for lake and stream fishing. Mixed construction: Often it wouldn’t be late in the evening before my father got home. Correct: Often it would be late in the evening before my father got home. Correct: Often my father wouldn’t get home until late in the evening. Many mixed constructions involve comparisons. For example: Mixed Construction: The backyard mechanic will find plastic much easier to work with than with metal. Correct: The backyard mechanic will find plastic easier to work with than metal. Correct: The backyard mechanic will find it easier to work with plastic than with metal. Using a modifying phrase or clause as subject or complement of a verb often produces a badly mixed construction. Mixed Construction: Without a top gave the new car model a very odd look. Correct: Without a top, the new car model looked very odd. Mixed Construction: Only one thing stops me from hurting you— because you’re my sister. (the only thing requires a substantive at the end, not because…) Correct: Only one thing stops me from hurting you—the thought that you’re my sister. The “reason…is because” construction is still not accepted in formal English. Catchall phrases like and others, etc, and the like suggest that the writer has run out of examples. Do not use them unless there’s a good reason. Mixed construction: The reason UP graduates perform so well in the job market is because employers think that UP graduates are competent. Correct: UP graduates perform well in the job market because employers think UP graduates are competent. Weak: Some cities in the Philippines like Quezon City, Manila, and the like, have populations that range over a million. Improved: Some cities in the Philippines, like Quezon City and Manila, have populations that range over a million. WEAK AND UNEMPHATIC SENTENCES Even though the sentence is technically correct, with its elements properly subordinated to throw the stress on the most important ideas, it may still lack force and impact. Weak sentences are usually caused either by shaky structure or by dilution with needless words and repetitions. Sentences ending with prepositions are by no means incorrect. A sentence with a preposition at the end is often more emphatic, and more natural, than a sentence that has a preposition buried within it. Trailing Constructions A sentence should not trail away in a tangle of dependent clauses and subordinate elements. The end of a sentence is an emphatic position. Put some important idea there. However, it is not necessary to make all your sentences “periodic” – that is, arranged so that the meaning is suspended until the very end of the sentence. Periodic sentences may sound contrived and formal: It was Swift’s intention that mankind, despite its ability to deceive itself, should be forced to look steadily and without self-excuse at the inherent evil of human nature. WORDY SENTENCES Unnecessary words and repetitions dilute the strength of a piece of writing. Be as concise as clarity and fullness of statement permit. Note that conciseness is not the same as brevity. A brief statement does not give detail; for example: “I failed.” A concise statement may give a good detail but it does not waste words: “Last month, I did not reach my sales quota.” Being brief is not always a virtue. But it is always good to be concise. In revision, look for unnecessary words in your sentences. Look with suspicion at such circumlocutions as “along the lines of”, of the nature of.” Avoid redundant expressions like “green in color”, “in the contemporary world of today”, “petite in size.” Although such sentences are compact and forceful, too many of them makes one’s writing sound stilted. On the other hand, the following sentence is inexcusably weak: A trip abroad would give me a knowledge of foreign lands, thus making me a better citizen than when I left, because I could better understand our foreign policy. The participial construction “thus making me a better citizen” is especially weak. Not only is it technically “dangling”, but it seems like an afterthought, like it was just an add-on to the sentence. Rearrangement and trimming could make it a better sentence: The knowledge gained on a trip abroad would help me to understand our foreign policy and thus make me a better citizen. Trailing Construction: It is in this scene that Leo finally realizes that he has been deceived by the promises of his sisters. Improved: In this scene Leo finally realizes that he has been deceived by the promises of his sisters. Avoiding Anticlimax When a sentence ends in a series of words varying in strength, they should be placed in climactic order, the strongest last, unless the writer intends to make an anticlimax for a humorous effect. Anticlimactic: The new sales manager proved himself to be mercilessly cruel in discharging incompetents, stubborn and impolite. Improved: The new sales manager proved himself to be impolite, stubborn, and mercilessly cruel in discharging incompetents. Stilted: This is the picture of the girl with whom I am in love. Improved: This is the picture of the girl I am in love with. Wordy and repetitious: If I should be required to serve a term with the armed forces, I would prefer to enter the Air Force, because I think I would like it better than any other branch of the service, as I have always had a strong interest in and liking for airplanes. Improved: If I have to enter the armed forces, I would prefer the Air Force, as I have always liked airplanes. Wordy: I am happy to announce that I grant your request. Improved: Yes. VAGUE SENTENCES If your sentences are to be clear, you must express your meaning fully, in exact and definite language. Gaps in Thought Try to put yourself in the place of your reader and try to read your sentence through his eyes. Would it be clear to someone without prior knowledge of what you are trying to say? It may be that because you wrote it and you know what you are trying to say, you jump ahead and “short circuit” your sentence. Not clear: Maturing faster because of parents’ divorcing does not hold true in all cases. The child may be rendered timid and insecure. Gaps filled in: When his parents are divorced, the shock may hasten the maturation of the child. But this does not always happen; divorce may also retard maturation and make the child timid and insecure. Inexact Statement Be exact in writing sentences. Make your meaning clear through exact phrasing. Inexact phrasing: Luxurious living results in expensive bills at the end of the month. (bills are not expensive; luxurious living is) Improved: Luxurious living brings high bills at the end of the month. Inexact phrasing: From my home are five high schools within a five-minute driving radius from my home. (one can reach the school in an automobile but not in a radius) Improved: Five high schools lie within a five-minute driving radius of my home. DICTION AND VOCABULARY POINTERS I. DICTION LEVELS OF USAGE 1. Standard English: Formal Formal English is usually written and is used in scholarly articles, official documents, formal letters, and any situation calling for scrupulous propriety. Informal (General) Informal or General English is the language, both written and spoken, used by the educated classes in carrying on in their everyday businesses. It is the level used in most books, magazines, newspapers, and ordinary business communications. Colloquial Colloquial English is the language of familiar conversation among educated people. It occurs frequently in informal writing. Formal Informal Colloquial comprehend understand catch on altercation quarrel row wrathful, irate angry mad goad, taunt tease needle predicament problem jam, fix exorbitant high steep 2. Substandard English Dialectical Words common to a particular region and not used throughout the country are part of the dialectical body of words. Slang These words are unconventional. They are vivid ways of expressing an idea which has no standard equivalent. Those that are widely used have a good chance of being accepted as Standard English. After all, some words that are considered as Standard now, like mob, banter, sham and lynch belonged to the slang words before. Ex: stooge, lame duck, shot of whisky, a bridge shark. Most slang words however are too violent to get accepted, and some are just a reflection of some people’s wish to be different. They quickly lose any precise meaning. These slang words have a poor chance of getting accepted in Standard English. Illiterate (or Vulgate) or Errors in Idiom Idioms are peculiarities of language. Idioms require that some words be followed by arbitrarily fixed prepositions. Take in Agree on Take up Agree with Agree to Angry at Angry about Argue for Angry with Argue against Argue with Argue about Some idioms demand that certain words be followed by infinitives, others by gerunds. Infinitive Gerund able to go capable of going like to go enjoy going eager to go cannot help going hesitate to go privilege of going Error in use of Idioms is unacceptable in Standard English. EXACT DICTION Choose words which say precisely what you mean. It is not enough to make sure that you can be understood; you ought to make sure that you cannot be misunderstood. 1. Choose specific words rather than general terms unless there’s a good reason for being general. General: For dinner we had some really good food. Specific: For dinner we had steamed lobsters and grilled tilapia. 2. Make your verbs work. Choose specific verbs or verbs that signify the specific action, rather than colorless or abstract verbs (e.g. occur, took place, prevail, exist). Colorless verb: He beat a hasty exit. Specific verb: He rushed from the room. 3. Do not use too explosive verbs or verbs that are too explosive for their context. Exaggerated: Her angry words pounced out upon him. Specific verb: She scolded him. 4. Do not use the passive voice when unnecessary because this leads to weak constructions. The passive voice is appropriate when the doer of the action is irrelevant or unknown. 5. Avoid jargon. People who are fond of jargon use them to dress up words; they hope to sound more “authoritative”. Certain key words betray the user fo jargon. He has an unhealthy fondness for factor, case, basis, in terms of, in the nature of, with reference to, elements, objective, personnel. Jargon: adverse climatic condition Improved: bad weather Jargon: Plant personnel are required to extinguish all illuminating devices before vacating the premises. Improved: Employees are asked to turn out all lights before leaving the plant. 6. Choose words with the exact connotation required by the context. In addition to their denotation or exact meaning, words have a connotation or a fringe of associations and overtones which make them appropriate in some situations but not in others. 7. Denotation Connotation a place of suggests family life, warmth, residence comfort, affection house a place of emphasizes physical structure residence domicile a place of has strictly legal overtones residence Inappropriate: “House, Sweet House” “A hat to fit every skull” EFFECTIVE DICTION In addition to being exact, your diction must also be effective; that is, you must make it easy and pleasant for a reader to grasp what you are saying. Keep your diction natural and sincere, be direct and concise, use fresh, unhackneyed phrases, and avoid needless technical language. Pretentious Language Do not decorate your sentences with pretentious language; doing so would make you seem insincere to your reader. Do not think that originality is achieved by avoiding ordinary words. Ordinary Word Strained Circumlocution spade implement for agricultural excavation dog faithful canine friends codfish denizen of the deep basketball player casaba-heaver hit the ball smacked the horsehide Do not also attempt to show your superiority by peppering your constructions with needless foreign words. Needless Foreign Phrase English Equivalent entre nous between us joie de vivre enjoyment of life faux pas social blunder sub rosa secret or secretly Sturm und Drang storm and stress Trite Rhetorical Expressions Guard against using hackneyed and stale expressions in your construction. Avoid clichés, hackneyed quotations, literary allusions and proverbs. Some hackneyed expressions: slow but sure speculation was rife mother nature easier said than done Clichéd quotations: all is not gold that glitters make hay while the sun shines Technical Language When writing something aimed at a general audience, you should avoid technical terms which are not commonly understood, even though more words are required to say the same thing in English. Appropriate Figures of Speech A figure of speech is a comparison, either stated or implied, between two things which are unlike except in one particular. Figures of speech are used to give color and vividness to writing, and they should be fresh, reasonable, consistent, and suited to the context in which they appear. When mixed, they should also not be incongruous. Incongruous mix: home This young attorney is rapidly gaining a foothold in the public eye. Awkward Repetitions Do not needlessly repeat words or sounds. Needless repetition: Probably the next problem we will tackle is the problem of rising school tuition. Improved: The next problem we will tackle is the rising school tuition. II. VOCABULARY KNOWING THE ROOTS At least half of the words in the English language are derived from Greek and Latin roots. Knowing these roots helps us to grasp the meaning of words before we look them up in the dictionary. It also helps us to see how words are often arranged in families with similar characteristics. For instance, we know that sophomores are students in their second year of college or high school. What does it mean, though, to be sophomoric? The "sopho" part of the word comes from the same Greek root that gives us philosophy, which we know means "love of knowledge." The "ic" ending is sometimes added to adjectival words in English, but the "more" part of the word comes from the same Greek root that gives us moron. Thus sophomores are people who think they know a lot but really don't know much about anything, and a sophomoric act is typical of a "wise fool," a "smart-ass"! Let's explore further. Going back to philosophy, we know the "sophy" part is related to knowledge and the "phil" part is related to love (because we know that Philadelphia is the City of Brotherly Love and that a philodendron loves shady spots). What, then, is philanthropy? "Phil" is still love, and "anthropy" comes from the same Greek root that gives us anthropology, which is the study ("logy," we know, means study of any kind) of anthropos, humankind. So a philanthropist must be someone who loves humans and does something about it—like giving money to find a cure for cancer or to build a Writing Center for the local community college. (And an anthropoid, while we're at it, is an animal who walks like a human being.) Learning the roots of our language can even be fun! Some common Greek and Latin roots: Root Meaning English words (source) aster, astr star astronomy, astrology (G) audi (L) to hear audible, auditorium bene (L) good, well benefit, benevolent bio (G) life biology, autobiography dic, to speak dictionary, dictator dict (L) fer (L) to carry transfer, referral fix (L) to fasten fix, suffix, affix geo (G) earth geography, geology graph (G) to write graphic, photography jur, just (L) law jury, justice log, logue (G) word, thought, monolog(ue), astrology, luc (L) speech biology, neologism manu (L) meter, metr (G) light hand measure lucid, translucent manual, manuscript, metric, thermometer operation, operator op, oper (L) work path (G) feeling ped (G) child pathetic, sympathy, empathy pediatrics, pedophile phil (G) love philosophy, Anglophile phys (G) body, nature to write physical, physics far off telephone,television ter, terr (L) earth territory, extraterrestrial vac (L) empty vacant, vacuum, evacuate verb (L) vid, vis (L) word to see verbal, verbose video, vision, television scrib, script (L) tele (G) scribble, manuscript LEARNING PREFIXES AND SUFFIXES Knowing the Greek and Latin roots of several prefixes and suffixes (beginning and endings attached to words) can also help us determine the meaning of words. Ante, for instance, means before, and if we connect bellum with belligerant to figure out the connection with war, we'll know that antebellum refers to the period before war. (In the United States, the antebellum period is our history before the Civil War.) Prefixes showing quantity Meaning Prefixes in English Words half semiannual, hemisphere one unicycle, monarchy, monorail two binary, bimonthly, dilemma, dichotomy hundred century, centimeter, hectoliter thousand millimeter, kilometer Prefixes showing negation Meaning Prefixes in English Words without, no, not asexual, anonymous, illegal, immoral, not, absence of, invalid, irreverent, unskilled opposing, against nonbreakable, antacid, antipathy, contradict opposite to, counterclockwise, counterweight complement to do the opposite of, dehorn, devitalize, devalue remove, reduce do the opposite of, disestablish, disarm deprive of wrongly, bad misjudge, misdeed Prefixes showing time Meaning Prefixes in English Words Before antecedent, forecast, precede, prologue After postwar Again rewrite, redundant Prefixes showing negation Meaning Prefixes in English Words above, over supervise, supererogatory across, over below, under transport, translate infrasonic, infrastructure, subterranean, hypodermic in front of proceed, prefix behind recede out of erupt, explicit, ecstasy into injection, immerse, encourage, empower around circumnavigate, perimeter coexist, colloquy, communicate, with consequence, correspond, sympathy, synchronize Suffixes, on the other hand, modify the meaning of a word and frequently determine its function within a sentence. Take the noun nation, for example. With suffixes, the word becomes the adjective national, the adverb nationally, and the verb nationalize. See what words you can come up with that use the following suffixes. Typical noun suffixes are -ence, -ance, -or, -er, -ment, -list, -ism, -ship, -ency, -sion, -tion, -ness, - hood, -dom Typical verb suffixes are -en, -ify, -ize, -ate Typical adjective suffixes are -able, -ible, -al, -tial, -tic, -ly, -ful, -ous, -tive, -less, -ish, -ulent The adverb suffix is -ly (although not all words that end in ly are adverbs—like friendly) READING COMPREHENSION POINTERS Coherence, Unity, Analysis and Inference I. FIGURATIVE EXPRESSIONS LITERARY DEVICES Simile – a figure of speech directly assessing a resemblance in one or more points, of one thing to another. It compares two things using the expressions like, as… as, resembles, etc. My patience is like traffic in EDSA—it is endless. Metaphor – a figure of speech that does say that something is like something or resembles something. It pretends that something is something. She is a rock — rigid and immovable. Synecdoche – a figure of speech by which a part is put for the whole or the whole for the part. A multitude of legs crossed the freeway. Personification – a figure of speech by which inanimate objects are bestowed with human traits. The heavens, cried bitter and noisy tears, whispering and screaming in turns. Metonymy – a figure of speech by which an object is used to represent another. Ladies and gentlemen, please lend me your ears. Hyperbole – a figure of speech by which a strong effect is achieved through an exaggeration and an overstatement. His neck stretched out a mile so that he could see what was going on. II. ORGANIZATION OF IDEAS COHERENCE I have only one word for you: coherence. Within a paragraph, sentences should be arranged and tied together in such a way that the reader can easily follow the train of thought. The relationship between the sentences must be clear. It is not enough that the reader knows what each sentence means. It’s equally important that he sees its relationship to the sentence that precedes it and to the one that follows it. It should also be clear to him the direction and thought where all the sentences are going. To achieve such coherence, you must arrange the sentences into some logical and recognizable order. The kind of organization will depend on the kind of material which is to go into the paragraph. PRINCIPLES OF ORGANIZATION Chronological Order (order of Time) - narration, process, examples and illustrations, cause & effect. Example: next; later; the following Tuesday; afterwards; by noon; when she had finally digested the giant burrito; as soon as; in 1998 Spatial Order - items are arranged according to their physical position or relationships. description, examples & illustrations. Example: just to the right; a little further on; to the south of Memphis; a few feet behind; directly on the bridge of his nose and a centimeter above his gaping, hairy nostrils; turning left on the pathway Climactic Order (Order of Importance) - items are arranged from least important to most important. examples & illustrations, description, comparison & contrast, analogy. o Psychological Order - This pattern or organization grows from our learning that readers or listeners usually give most attention to what comes at the beginning and the end, and least attention to what is in the middle. Example: more importantly; best of all; still worse; a more effective approach; even more expensive; even more painful than passing a kidney stone; the least wasteful; occasionally, frequently, regularly Topical Order - classification & division, comparison & contrast, analogy, definition, examples & illustrations. Example: the first element; another key part; a third common principle of organization; Brent also objected to Stella's breath III. IDENTIFYING AN IRRELEVANT SENTENCE UNITY AND CONCISENESS A construction must have unity; that is, its parts and elements must be working together to clearly say something. It must also be concise; that is, it says in as few words as possible, what is needed to be said. An irrelevant sentence is a sentence that does not contribute anything to the main thought of the passage or selection. It doesn’t help move the paragraph along to its conclusion. In short, it is not necessary. As a simple technique, look for the sentence among the selection that does not cooperate with the rest of the sentence, in terms of direction and support value.