Cyrano de Bergerac´s Space Voyage: Copernican Cultural Paradigms in Early Modern Science-Fiction

advertisement

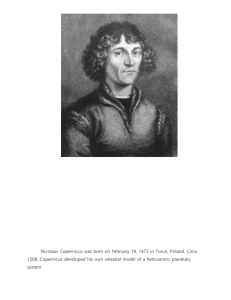

Cyrano de Bergerac´s Space Voyage: Copernican Cultural Paradigms in Early Modern Science-Fiction Universidad de La Salle Bogotá D.C, Colombia, 2019 Facultad de Filosofía y Humanidades Director de Tesis: Doctor Germán Ulises Bula Caraballo Monografía de Pregrado: David Stephen Aronson Cerezo TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 Ptolemaic World System 1.1 Pre-Copernican Astronomical Instruments.......................................................................... 5 2.2 Ptolemaic Trigonometry and Astral Maps ........................................................................... 7 2.3 Aristotelian Geocentrism and Astronomical Models ......................................................... 10 Chapter 2 Copernican World System 2.1 Copernicanism and the Rejection of Geocentrism ............................................................. 12 2.2 Spatial Symmetry and Uniformity....................................................................................... 15 2.3 Giordano Bruno’s Idea of Infinite Space ............................................................................ 18 Chapter 3 Bergerac´s Science-Fiction 3.1 Space Flight and VTTM ....................................................................................................... 22 3.2 Science-Fiction Optimism ..................................................................................................... 25 3.3 Human Intelligence and Alien Species ................................................................................ 27 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 31 Bibliography ................................................................................................................................ 34 Para mi abuela Blanca, un abrazo lleno de gratitud y amor, por lo que me ha empujado a lograr un futuro a partir del esfuerzo y la educación. Con lo que me has dado espero buscar algo más grande en la vida, y sin ti nunca hubiera llegado a este punto. Gracias por pensar en mi bienestar y mostrarme un bueno camino para seguir en la vida. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Para mi madre y padre, Clavia y Harvey, con tenerlos en mi vida he tenido el privilegio de estar rodeado por unos espíritus libre pensantes que me han infundido la paciencia, la humildad, la alegría de la crítica, la rebeldía, y el buen humor. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Para mi director de tesis, el doctor Germán Bula bajo su tutoría, con su liderazgo firme para esta propuesta de investigación, se ha llevado a la culminación una gran idea que empezó con la sugestión de estudiar la ciencia-ficción desde sus cimientos en la cultura pre-Copernicana. "And for my part, Gentlemen," said I, "that I may put in for a share, and guess with the rest; not to amuse myself with those curious notions wherewith you tickle and spur on slow-paced time; I believe, that the Moon is a world like ours, to which this of ours serves likewise for a moon." (Cyrano de Bergerac, A Voyage to the Moon) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ¨Looking at the moon, the convert to Copernicanism does not say, "I used to see a planet, but now I see a satellite." That locution would imply a sense in which the Ptolemaic system had once been correct. Instead, a convert to the new astronomy says, "I once took the moon to be (or saw the moon as) a planet, but I was mistaken.¨ (Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions) Introduction Cyrano de Bergerac, French libertine author, wrote the science-fiction novel Voyage to the Moon1 (henceforth VTTM), published posthumously in 1657. The story describes an unnamed protagonist who seeks to travel to the Moon to locate extra-terrestrials who had once visited the Earth. The narrative starts as the protagonist randomly opens a book in his private library written by Cardanus, the fictionalized figure of Jerome Cardan, 16th century astrologer, demonologist and natural philosopher. Cardanus has met these aliens beforehand, and has written a chronicle about them detailing the information of their place of origin. After finding and reading the chronicle in his own library, the protagonist invents his own propulsion technique to reach the Moon and corroborate if Cardanus´s chronicle is true or false. In VTTM, after arriving to the Moon and being taken in as a guest by the aliens, one of them informs the protagonist that he has visited the Earth before. The alien knows a great deal about human culture, and has even lived among humans at times. The revelation of alien knowledge of human affairs amounts to a commentary on the limits of human experience, positing that aliens are at the highest rung of a cosmic hierarchy of intelligent organisms, and portraying human science and culture as inferior to the alien´s culture and science: ¨…Beast-like men, catching hold of me by the neck, just as wolves do when they carry 'away Sheep, tossed me upon his back, and brought me into their town …when I knew they were Men,…when these people saw that I was so little, (for most of them are twelve cubits long) and that I walked only upon two legs, they could not believe me to be a man.¨ (Bergerac, VTTM: pg. 33) 1 The original title in translation is The Other World: Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon. We will be using the translated title from the 1889 re-publication by Doubleday and Mcclure Co. 1 VTTM portrays the rather novel idea (made possible in part by new scientific developments) of the possibility of alien civilizations on other heavenly bodies; this idea, in turn, relates to intriguing new perspectives for humanity´s place in the cosmos. Before the belief in aliens was widespread, as it is today, to think of life outside Earth was the result of believing in new ideas, like heliocentrism, in a way that was not determined by contemporary cultural values. Science-fiction, as a genre of modern literature, explores heretofore unknown possibilities of modern science and technology. This paper explores two features of Cyrano´s work in a wider cultural context: (1) the possibility of space flight and (2) the possibility alien life. These will show how the work is part of an important cultural moment in early modernity when the idea of sciencefiction became possible in early European humanism. We can call Bergerac´s work science fiction, avant la lettre, because it is a literary exploration of the possibilities of technology, based on the cutting edge science of his time (what would then be called “natural philosophy” 2). VTTM alludes to the development of heliocentrism by giving a description of life on other planets, as well as detailing a physically feasible device for reaching planets outside Earth. We will look at the relationship between VTTM´s significance as a work of fiction, and the paradigm shift in astronomy and culture to be developed later, an object crucial to our inquiry, to examine why scientific innovation and cultural production are interrelated. To this end, we will use Thomas Kuhn´s concept of the paradigm, both in its original narrow sense as a structure for scientific revolutions, and in a sense that includes culture. Kuhn used the term ´paradigm´ to refer exclusively to scientific fields and their historical accumulation of knowledge in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1963). Others like Fritjof Capra in The Systems View of Life (2014) and 2 See; Dear, Peter What is the History of Science the History of? Early Modern Roots of the Ideology of Modern Science. 2 Clifford Geertz in The Interpretation of Cultures (1973), have used the term in a broader cultural sense. Bergerac’s libertine science-fiction is a literary work that contributes to the rise of the newly minted natural sciences and liberal arts, in Europe, during the 17th century. VTTM´s science-fiction story provides an interpretation of heliocentric astronomy, originating from the publication of Nicholas Copernicus´s De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium in 1543. Later, the Copernican theory was developed in the works of Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, Christopher Huygens and Isaac Newton; as well as with philosophical works by Giordano Bruno, Rene Descartes, Tommaso Campanella and Bergerac´s own teacher, Pierre Gassendi. In contrast, Claudius Ptolemy´s astronomical body of work validates the general worldview of geocentrism, which refers to the Ptolemaic world system3, which, as I hope to show, is both a scientific model, and a broader cultural view. This analysis of Bergerac´s cultural paradigm shift will be developed in the following manner: i. Chapter 1 is devoted to the Ptolemaic world system. The cosmological and astronomical model of geocentrism will be explained in relation to the Ptolemaic world system´s astrological and physical perspective. Aristotle´s philosophy will be used as an example of how the cosmos was assumed to exist in a pre-Copernican worldview. Thomas Kuhn´s work on Ptolemy will be introduced in this chapter to analyze how astrology contains a cosmological aspect of geocentric astronomy. Our aim is to reconstruct the astronomical 3 Galileo´s work Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632) introduces Copernicus´s and Ptolemy´s astronomical work, each as its own ´world system´. 3 model of geocentrism from this chapter onwards so as to clearly see how the knowledge of astronomy factors into the possibility of visiting inhabited worlds. ii. Chapter 2 treats the Copernican world system analyzing the problem of the establishment of the heliocentric planetary system. The implication of a rotating and orbiting Earth, will be looked to as a solution for the problem of geocentrism´s model of the Earth´s physical attributes. From here, we will be delving into the culture of astronomical model which upturned the established geocentric paradigm. In this chapter we look clarify how Copernicus came to posit that planets exist in heliocentric space, by hypothesizing the nature of moving planetary masses in space. Giordano Bruno´s work on the plurality of words will be introduced to analyze cultural Copernicanism in a 17th century perspective, as it is similar to Bergerac´s heliocentric science-fiction, in the sense that the possibility of life on other planets represents a contemporary cultural view. iii. Chapter 3 will treat Bergerac´s novel, and its sequel, and focus on the relation between physical and astronomical concepts i.e, mass, motion, uniformity, which are related to the speculation of space travel outside Earth. An exposition of the alien races and environments is useful to explain the context of Bergerac´s views on natural science, and to bring up the issue of human humility in relation to the possibility of discovering intelligent non-human consciousness. Science-fiction motifs, like space travel and alien worlds, contribute to the progress of the natural sciences and liberal arts, and stimulates the cultural production of the Copernican cultural paradigm. In relation to this, we will briefly touch on the subject of space travel as it relates to early modern optimism, as reflected, as an example, in Picco della Mirandola´s views on the possibility of the transformation of humanism into new forms of imagination. 4 1.1 Pre-Copernican Astronomical Instruments The influence of the Sun, Moon’s and zodiac´s motion, the shift of seasons and different hours of the day, has been studied by astrologers to observe terrestrial bodies’ relationships to the celestial proportions of space. The confirmation of the position of stars, to a Hellenic astrologer (Tester, (1987)), is an exercise which is based in the measurement of time 4, aiding the seeking good fortune in everyday human existence. Astrology has its origin in Babylon, and is traced to Greece starting in the 4th century B.C.E. The sun-dial (Figure 1) uses daylight to calculate time from the geometrical plane of the Earth´s surface, by way of making subdivisions of the full day and night into hours, relating them to other units of time that vary throughout the course of one year. The gnomon at the center of the sundial, a shadow caster, marks time using numerical ratios that correspond to astronomical lines running through the Earth´s horizon; a fixed, geocentric circle of the length of a diameter, partly below the surface, and pointing away at the celestial firmament around Earth. Figure 1. Portable Sun-dial found in Qumran. (The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, © Peter Lanyi) 4 The social aspects of astrology are separate from their value as predictive models. See; Riley, Mark (1987): p. 242. 5 The armillary sphere, also known as an astrolabe5, (Figure 2) could point to the position of a celestial body describing the same line of sight, extended into the heavens and displaced from the circular plane of reference of the Earth´s horizon. These tools represented a feasible astrological mechanism for obtaining measurements; and of obtaining the astral position of any stars´ displacement above the Earth´s horizon, from a stationary point marking the Earth´s astrological center. Figure 2. 1. Ecliptic sighting ring. 2. Altitude sighting line. 3. North-South ecliptic ring. 4. East-West equatorial ring. 5. Secondary altitudinal sighting ring. 6. Meridional sight line. Diagram for Construction of Astrolabe (Taken from Almagest Tran. Toomer (1984)) b, b. Sighting holes. d, d. Pivots marking meridian line. e, e. Pivots marking ecliptic poles. Astrologers studied the Earth´s sky, and the position of astral bodies using mechanistic tools, during the first centuries before the first millennium (Wright, (2000)). They believed that the heavens were moving perpetually in circles thought to exist outwards from a heavenly center, which refers to the Earth´s surface as if it were poised atop a single axis of motion. An astronomical geometric plane marks the Earth´s equinoctial points (Couprie, (2013)), determining the changing of seasons. By evaluating geosynchronous lines of motion inscribed on the celestial firmament, a single point of reference is revealed under the influence of other heavenly bodies´ mass and motion6, with instruments that measure the geometrical displacement of matter around Earth. 5 Hipparchus may have invented the astrolabe, also called an armillary sphere. See also, Ptolemy, (1984): p. 217-219. There are theoretical and practical aspects to astrology which require the use of astronomical models: See; Ptolemy, (1882): Book I. Chapter I-II. 6 6 1.2 Ptolemaic Trigonometry and Astral Maps The Ptolemaic astronomical system, proper, is revealed in the book known as the Almagest. The name means ´The Greatest´; which was given to the text by Arabic translators who changed the original title from Mathēmatikē Syntaxis; iconizing the eminence it held at the time as a milestone for culture. Ptolemy, astronomer and philosopher from Alexandria, during the 2nd century C.E, believed in a spherical globe model of Earth and heavens. He posits a spherical globe Earth, which does not rotate on its own axis nor revolve around any other spherical object7 about its horizon; a circle of the Earth´s surface that is a fixed, and visualized in relation to physical objects on Earth, from a point of reference marking the celestial firmament influence over the terrestrial surface. The astronomical plane of Earth is traversing an astronomical position in relation to the observation of the horizon´s plane from the Earth, staring out at the same portion of sky at all times. The basic terms used to mark a trigonometrically observed point in the sky from the Earth´s horizon are the zenith, the line directly above one´s head from the horizon; the nadir, the line leading below one´s feet through the horizon. And declination, the angular velocity where a star is moving, marking distance moved in space according to the observer´s place, as a moving circle atop the Earth´s center. Other planets also have longitude and latitude, the mean lines on an astronomical plane of motion, relative to Earth´s center and its surface shape. The celestial sphere is only partly visible from the Earth’s horizon. The portion that is occluded by the Earth´s surface will come into view 7 The computation of motion and position for objects around Earth is formulated as geocentric model. See: Washburn, Alan R. Orbital Dynamics for the Compleat Idiot. 7 during certain time periods, but is blocked in space by the other side of the Earth´s stationary diameter. Geocentric Circle of Longitude Figure 3. Taken from: Glen Van Brummelen ¨Taking latitude with Ptolemy: Jamshīd alKāshī's Novel Geometric Model of Motions¨ (2006) Q. Equant. C. Deferent eccentric circle centrum (P, C, E, Q) E. Earth (Zenith, and Nadir of E and Altitude of P are measured from the prime meridian). A. Diameter of Deferent. P. Planet. G. Epicycle circle of P. Cm. Mean Motion of Epicycle P. Am. Mean motion of Anomaly of G. Av. True motion of Anomaly of G. In Ptolemaic trigonometry, an equant point (Figure 3) is below the Earth´s surface, slightly away from its center (Ptolemy, (1984): p. 41-43). The cosmos is believed by Ptolemy to be characterized by the cosmos´s primary motion, which goes unceasingly from east to west carrying the heavenly spheres every hour of the day and night, and for seasonal changes (Ptolemy, (1984): p. 38). The ecliptic plane is the geosynchronous geometric plane that computes the orbital positions of multiple heavenly bodies, according to celestial coordinates of longitude and latitude, on a heavenly sphere. The overall material shape of the cosmos yields a sphere displaced along its two poles (See Fig. 4. Note, within the outer boxes on the map are astrological signs), where the immobility of the Earth´s horizon bisects the zodiacal circle. In the Ptolemaic system, the Earth does not move due to its incredible weight and density (Ptolemy, (1984): p. 44). Thus, as the ecliptic plane moves across the Earth´s horizon, it is not affected by displacement of mass of any other part in the cosmos, where all heavenly spheres move along the zodiac circle. In this way of thinking that Earth 8 is an immobile point of matter in space, upon the ecliptic plane and bordering the zodiac´s frame of reference, its location in the center of the cosmos is culturally important. This explains why it is uncontroversial to think how and why the astrological notion saying that stars influence the Earth is quantifiable. If the Earth is a fixed point in space around which everything moves, its center affects the existence of all other moving objects. Figure 4. (Taken from Abbo of Fleury, Computistical, astronomical, and cosmological compilation, Photo: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz.) The word ecliptic, in ancient Greek, means ´to cut the zodiac in two´, referring to how the ecliptic circle was measured from two poles that served as a central axis for the measurement of heaven’s total space. The astral map (See Fig. 4), a cosmographical study of apparent motions and heavenly time, serves the purpose of directing the Ptolemaic astrologer who intends to establish the apparent magnitude of the geocentric ecliptic plane, where the fixed stars and the planets report mean time and position (horoscopy) upon the Earth´s stationary mass and diameter, described beforehand using observational instruments and data. In the next section, from the technical description given here of geocentrism we will know move on to cultural aspects of pre-Copernican culture, using Aristotle as an example. 9 1.3 Aristotelian Geocentrism and Astronomical Models Let us examine a traditional approach to astronomy, touched on by Kuhn8, as it is determined by studying the Earth´s position in respect to other heavenly bodies. Aristotelian studies of cosmology represent contributions to the Ptolemaic world system that are important for the analysis of Earth´s status as the center of the whole cosmos. For Aristotle the problem of a planet´s status can be thought of in relation to the central, immobile point around which all other heavenly bodies revolve. Aristotelian philosophy is steeped in spherical cosmology9. The Earth is located in the exact middle of the immensity of the heavens, as a natural axis for celestial motion and mass to be displaced from one place in space to any other. Aristotle refers to the difference between sub-lunar and super-lunar spatial regions, and posits that causes operate differently in either realm10; the sub-lunar being a frame of reference that is fixed in space. The super-lunar region´s stars display diametric motion that determines circularity about a center, either downwards towards the center, upwards away from the center, and both upwards and downwards on a line about the center. Circular motion can be bidirectional and respective from a stationary cosmic epicenter, the Earth´s surface and fixed mass. 8 This is referring to the cultural aspects of astronomy: ¨That phrase, "Ptolemaic astronomy," refers to a traditional approach to the problem of the planets rather than to any one of the particular putative solutions suggested by Ptolemy himself, his predecessors, or his successors.¨ (Kuhn, T. S. (1957): p. 66). 9 The natural form of the sphere must necessarily be seen in the celestial firmament, proportionally to a fixed center. See, Aristotle, On the Heavens; Book II. 10 The role of generation and corruption in nature is defined as a conditioned principle (ἀρχή) by Aristotle. The prime motor, or unmoved mover, is the first cause for all conditions of all possible objects. See, Aristotle, Metaphysics; Book XII. Aristotle, On Generation and Corruption; Book I, Part 6. 10 Planetary retrogressions show the reversal of circular motion at different points upon the ecliptic plane (See Fig. 5 for retrogression of Mars), where a star goes in one direction, stops, and then goes in reverse motion for a certain time period, before returning again to the first direction. The mechanisms that were responsible for planetary retrogressions were not considered exceptional motions to be investigated further, and did not consistently link super-lunar motion to any other part of the cosmos. The Earth´s weight was also considered to be heavier than any other object in space. In addition, it was considered that the sub-lunar realm represented different relationships for moving masses. Figure 5. Taken from Kuhn (1957) (West) (East) We can see how in a pre-Copernican worldview the great number of untested hypotheses relating to physical matter favors a geocentric view of time and space. The logical opposition between weight and lightness was assumed to be true by virtue of observation. Weight and lightness are considered as determined qualities of space. In addition, motion itself was imagined as if it were a theoretical truth that corresponded to geometric and arithmetic computation, without any overarching concerns relating to broader mathematical-astronomical models. Aristotelian models of time and space lack the integration of scientific models of observation that lead to understanding concrete empirical, naturalistic properties of physical bodies. 11 2.1 Copernicanism and the Rejection of Geocentrism Copernicus sought to challenge the Ptolemaic geocentric model on various different levels, which are based in the reflection on the Sun’s place in space, as well as certain questions pertinent to the development of mathematical astronomy. Copernicanism affirms the postulate of the Earth´s rotation upon its diameter; and also questions how the Earth does not occupy the center of the heavens (Copernicus, (2002): p. 22-26). The Earth´s central place in the heavens is incorrectly perceived by not knowing what a planetary system is, as a feature of space. Astronomers before Copernicus had confirmed the existence of anomalies in the astral position of the zodiac´s erratic motion of precession, but none had considered that these anomalies arose from misperceiving Earth´s place in a planetary system. The Earth´s immobile position, and thus its, relation to other heavenly bodies, is being put into doubt. The ecliptic plane, which was an astral map unfolding before the celestial firmament, before the earthbound sky gazer, has to be reimagined as if physical measurement in a geocentric astronomical plane, corresponded to heliocentric spatial properties. Earth´s twenty four hour daily rotation really belongs to itself, and does not originate with motion about the celestial sphere that planetary masses have to unceasingly obey. From the closest to the farthest object away from the Earth, relatively, a new model should be studying the new synchronous, symmetric space that planets move through. Copernicus´s observational prowess allowed him to rectify the discrepancies that were known about the Ptolemaic world system. The Julian calendar [46 B.C.E] is replaced by Gregorian calendar [1582 A.C.E]. The previously used calendar was off by 10 days due to a shift between the 12 measurements of the tropical year and sidereal year11. For computations performed fifteen hundred years apart, which changes by less than a tenth of a degree per year, the error in measurement produces a deviation in prediction of the seasons that is evidence of an incorrect astronomical model. He considered that the reason for the deviation, for the Ptolemaic system, is related to incorrect assumptions about the cosmos´s symmetrical material order. The Copernican ecliptic plane is no longer distributing an equant point along the computable astronomical plane of the sphere of the fixed stars12. There is an eccentric circle from the solar center enveloping the entire planetary system, where spinning planets are moved by epicycles with an individual, twofold axis of motion. One motion is daily rotation; the other motion is yearly orbit. A spinning planetary globe is the source of many visual distortions that seem like real astronomical perceptions, but in fact are mere optical effects caused by the anomalies of Earth´s astral position. The commensurable effects of planetary spin on visual representation is called commutation13 by Copernicus. Planetary retrogression is now understood, primarily, as a visual distortion caused by Earth´s moving horizon in space. This distorted frame of reference applies to a rotating, symmetric astronomical plane, seen coursing uniform space from the fixed solar center, where spinning planets follow the uniform motion of a central mass, about a circumference where planets and stars are determined by orbital dynamics. 11 The sidereal year is longer than the tropical year by 20 minutes. The different measurements result from the astral position of the Earth and its varying speed during orbit. 12 This is a view in philosophy of science that deals with scientific facts as features of particular research programs, see; Lakatos, Imre; Zahar, Elie, Why did Copernicus´s Research Program Supersede Ptolemy´s. 13 Commutation, traditionally called parallax, is the visual effect of the distance perceived between two observers who are moving on two different planes of motion, where one plane of motion appears to overtake the other, but has not done so as a matter of fact; see, Rosen, Edward Copernicus and his Successors (1995): p. 79. 13 Subsequently his model was determined to take measurements of the Earth´s position and temporal period inside a heliocentric planetary system more accurately. The rate at which the zodiac´s Figure 6. Taken from C.A Gearhart (1985) constellations rising and setting marks measures the Earth´s true position14 in space is affected by commutation. A better measurement of the zodiac´s retrocession15 establishes true measurements of Earth´s spatial-temporal position; proving that greater economy is achieved, in theory, by realistically describing the coherent spatial-temporal relationships of planetary systems (Fig. 6. S is the Sun´s center; C is a deferent circle of motion; P is any planet´s epicyclical axis of orbit around the Sun; A, A-1, and T are anomalies computed from S and P). In order to figure out how to visualize space mathematically beyond the Earth´s sky´s earthbound east-west horizon, we look at the solar frame of reference which defines the ecliptic plane differently than in a geocentric astronomy. The sun´s fixed position in between 7 orbiting objects (Moon, Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Saturn, and Jupiter) is a central axis in space. Since we are no longer thinking of Earth as an absolute center that can be visualized in space we must now imagine Earth´s position as a planet in a system of spheres. A new configuration of space girds the planetary system Earth is moving in, in tandem to other celestial spheres, as a planet. 14 For discussion on the precession of the tropical and sidereal year that explains the Earth´s place in space in relation to the measurement of time, see: Swerdlow, Noel M. Hipparchus's Determination of the Length of the Tropical Year and the Rate of Precession, and Neugebauer, O. The Alleged Babylonian Discovery of the Precession of the Equinoxes. 15 Ptolemy used the numbers for the zodiac´s precession about an axis, collected from the work of Hipparchus, whom says it is equal to 36,000 years (It is actually known to be about 26,000 years today). 14 2.2 Spatial Symmetry and Uniformity Copernicus developed a symmetric spherical astronomy and heliocentric cosmology. The Sun´s frame of reference as a central point in space reimagines the astronomical plane, where heavenly bodies rotated and revolved in orbits, about a new, complex axis of motion that is not geocentric. The feat of establishing a new paradigm for Copernicus is achieved, technically, using his own trigonometry using epicycles, eccentric and deferent circles16, to describe uniform motion (See Fig. 6) about the circumferential position of a heliocentric sphere; and shunning the use of a fixed, equant point. The triplication of measurements, necessary to calculate motion, and which are found in Ptolemy’s mathematical-astronomy, was replaced with a simpler model by Copernicus (Compare Fig. 6 to Fig. 3). Celestial observations are now possible for Copernicus, in his mind´s eye, from the point of view of the attraction of mass to mass; the ´kingly throne´ of the solar harmony, where the omnipotent cosmic center relays motion and mass about the ecliptic plane. Copernicus described the correct order of the planets, as they lie outwards from the Sun´s center in this way (Copernicus, (2002): p. 26-31). The Sun´s place was referred to as a harmony; carrying lesser and greater heavenly bodies, and their orbits, by conveying mass across a starry center in space (Copernicus, (2002): p. 30-32). The detection of true position for Sun, Moon, and Earth is essential for a heliocentric model where planetary motion corresponds to space, and earthbound observers can realistically compute harmonious, mathematical-astronomical spatial properties. The correct position determined by the Copernican model is related to the horizon´s spatial displacement from a spatial center, and to the production of a fixed astronomical table of 16 Copernicus´s mathematics simplifies the three point computation of astral position. See, Gearhart, C.A Epicycles, Eccentrics, and Ellipses: The Predictive Capabilities of Copernican Planetary Models. 15 measurements17. The center of a solar system will be coherently proportioned to other spheres that represent symmetric motion and distance18 about an axis that displaces space from a heliocentric center. The analysis of space, for a planet like Earth, refers to the computation of apparent motion for heliocentric planets (see Fig. 7), where the Earth Figure 7. D C E arranges motion symmetrically about the ecliptic and defines the center of the zodiac19. It can be observed from the Earth (point E), where the rising of signs (point B and point C) and their setting (point A and point D), B A contiguous to the Earth´s horizon (lines BED and AEC). This shows us how their appearance upon the Earth´s horizon completes a full circle of 360 degrees (See Fig. 8) as it follows its yearly and daily motion. The success of Copernicus´s model, in looking at the zodiac´s immeasurable distance from Earth, can be interpreted as a confirmation of the precession of the equinoxes20. He discovered that the precession of the equinoxes is not caused by the apparent Figure 8. eastward motion of stars in the sky. It is a visual distortion, or commutation, of the Earth´s own inclined axis of rotation and 17 The tropical year is measured in relation to the sidereal year to achieve greater accuracy in the measurement of the length of planetary orbit. See: Abers, Ernest S.; Kennel, Charles F., The Role of Error in Ancient Methods for Determining the Solar Distance. 18 Geokinetic motion is possible for spherical mass, see: Knox, Dilwyn Copernicus´s s Doctrine of Gravity and the Natural Circular Motion of the Elements. 19 If one defines the center of the zodiac in relation to a geokinetic body one must calculate the Sun´s position into a variety of astronomical models i.e., the distance of Venus, the precession of the equinoxes, eclipses etc. See, Hanson, Norwood Russell The Copernican Disturbance and the Keplerian Revolution (1961): p. 178-179. 20 The same constellations of the zodiac appear sometimes during winter and other times during summer. In summer, day is longer than night, and in winter, night is longer than day; the equinox are the 4 points of equal day and night during every year. Precession is the predicted shift in the observation of the seasons´ equinoxes, from the zodiac´s apparent motion. The first to discover axial precession was Hipparchus. 16 revolution (Earth is tilted 23.5 degrees on the ecliptic) that produces the aforementioned retrocession of stars in the firmament over a zodiacal cycle. To Copernicus, the naked eye´s illusory perception of Earth´s immobility is also proof that the position of heavenly bodies in the celestial firmament, such as the zodiac, do not always provide meaningful data to accurately compute distances for two spherical orbital relations, across any distance in space. Day and night, therefore, are not sequential sections of the Earth´s horizon, which coincide with the movements of the Sun and Moon; day and night are just units of motion found in between Sun, Earth, and Moon. This new perspective disregards the a priori observation of the human senses, in a Ptolemaic spatial sense is predetermined through the contiguity to the Earth´s mass, and is inclined to think of day and night as features of Earth´s natural form. The motion of stars for Copernicus was seen to represent a well-organized harmony of mechanical motions, which favors an external view of Earth´s temporal and spatial phenomena. The Copernican heliocentric model undermines humanity´s belief in the uniqueness of Earth, and therefore of itself, contrary to religious tradition. This implies the de-centering of human culture, to the view of the human being as an entity in nature that now lives on a moving planet. Humanity is inhabiting a planet, by virtue of a planet´s physical properties identical to that of other planets in the immensity of space. In accordance, human experience is limited by natural laws and the properties of matter. A critique of religion by secular science is a topic that will not be treated here since it implies a more detailed analysis of the relationship between religious institutions and modern science. The Copernican cultural paradigm brings about a new conception of reality based in reason, all the while bringing up the possibilities of a new scientific worldview. 17 2.3 Giordano Bruno’s Idea of Infinite Space Cultural paradigms can arise from astronomical traditions in modern culture. The history of cultural Copernicanism relates to the possibilities of astronomical discovery in cultural products that portray life outside Earth. New interpretations of a heliocentric planetary system add to the cultural relevance of the Copernican revolution: ¨Most of the essential elements by which we know the Copernican Revolution — easy and accurate computations of planetary position, the abolition of epicycles and eccentrics, the dissolution of the spheres, the sun a star, the infinite expansion of the universe — these and many others are not to be found anywhere in Copernicus' work. In every respect except the earth's motion the De Revolutionibus seems more closely akin to the works of ancient and medieval astronomers and cosmologists than to the writings of the succeeding generations who based their work upon Copernicus' and who made explicit the radical consequences that even its author had not seen in his work.¨ (Kuhn, (1957): p. 135) The many followers of Copernicus such as Kepler, Galileo, and others, develop their own versions of Copernican world systems, so that new data and observations are added to the planetary system established in his new astronomical model. Astronomers add hard scientific data: i.e., Galileo´s observation of the rotation of the Sun´s surface using a telescope, or Kepler´s observation that orbits are elliptical. Copernicus could not have imagined in the future how so much that has been based on his theory is related precisely to the discovery of a heliocentric rotation about the cosmos´s many axes of motion; describing a sun around which other moons and planets revolve and spin. 18 Giordano Bruno, the philosopher infamous for publicly defending heliocentrism before the Catholic inquisition, was a student of Copernicus´s theory. He was executed for it, at the Campo di Fiori in 1608. It was Bruno who propounded the idea that space is infinite, and contains an infinity of inhabited planets. According to Bruno, God creates new living beings that populate the universe because an infinite universe is fine-tuned to receive matter in proportion to an infinite, divine creative force. If there is a planetary system with a quality of matter creating life on Earth, then, consequently, there should be many suns in the rest of the universe that do the same thing, because of God´s infinite creativity; the propensity to create life. Bruno´s thesis of life on other planets is derived from Copernicus´s intuition of space. The homogeneous uniformity of nature is generated in a planetary system according to the possibility of life that links suns to earths. An infinite universe is generated in the infinite dimension of space according to a natural principle of a metaphysical condition of existence for corporeal and incorporeal space: ¨The Stoics distinguish between the world and the universe, because the world is everything that is full and has a solid body; the universe is not only the world, but includes void, external space; that is why they say that the world is finite, but that the universe is infinite.¨ (Bruno, (1993): Dialogue I. 398) Physical beings, occupy empty space, and are perceived by intellect, according to its transmutable material properties and forces. Matter is arranged in bodies that exist in the vastness of empty space. Bruno´s thesis of innumerable earths is a response to the question about the existence of life on other planets, and is guided by the discoveries of the Earth´s self-propelled axis 19 of rotation and its direct relation to a heliocentric planetary system21. Life is a process that can be likened to the physical transmutations of forces, where there is an infinite mixing of physical substances and forces. Bruno imagined the causes and effects of living, animated beings are correlated to a dichotomy between a sun, and the earths and moons that surround it. In Bruno´s infinity, all animated objects are determined to exist around a void, which accompanies all the physical processes related to planets22 that have water and can sustain life; and for suns that possess fire and give live, animating matter from within and without organic bodies. Bruno believed that there was a likely possibility of there being an infinite amount of habited worlds like Earth, in other parts of the cosmos, where force is exerted on finite substances, such as water, fire, ether, and earth; from which living organisms are composed. The fundamental constituents of matter, atoms, are carried in space by a creative force, because God has created a universe that will snap into place from nothingness, and assume by nature any physical shape or aspect23. If physical force can become part of the space that defines finite, animated bodies, then there is still a perfect motion of space that is derived from infinite space, created extrinsically from empty space24 in physically animated bodies. There is no defined point in an infinite universe where up, down, left, right describe how mass and motion snaps into place from nothingness; nor can we directly know the mind of God that creates matter ex nihilo. Consequently for Bruno, atoms are the perceived products of infinite earths, suns, and moons that 21 Bruno believes that the soul is responsible for motion in all finite bodies, and in the whole of the universe as well. See, Bruno, (1993): Dialogue II. 432. 22 Earth´s movements for Bruno are both finite and infinite. These movements are not finite and physical, but manifested by divine matter. See, Ibid. Dialogue I. 391-392, Dialogue II. 407-408. 23 Atoms have an infinite path for motion, and for the alteration of their mass there are infinite possibilities from their generation in the divine intellect. See, Bruno, (1993): Dialogue II. 413-414. 24 Marsilio Ficino was the first to translate Plato into Latin in the 15 th century. His Platonic cosmology is based in an intrinsic principle of matter and intellect that is tethered to a world-soul. See: McMullin, E. (1987); p. 61. 20 make up a planetary system, as infinite space is created in proportion to the organic beings that populate it. Space is disposed to receive spiritual matter, of a determined natural property, because there will always be animated bodies 25 that assume the spontaneous generation of physical and living forces in a universe that is infinite. The infinite amount of possible species that represent living matter26 is unconstrained by a relative limit, a single center of force in space, where atoms and physically animated matter originate in physical bodies. In an infinite universe, every physical location can be considered a center for living matter, as much as it is considered to be inside or outside physical bodies, outside of empty space, as a physical force that creates life, as well as new planetary systems, from infinite, empty space. The thesis of Bruno´s infinitely populated version of the cosmos is also represented similarly by Bergerac´s science-fiction narrative where planetary systems exert force, in external space. Thus, Bruno and Bergerac´s thought has a common consciousness for a new vision of the universe, where the universe is being infinitely altered, as God is creating new physical forces, and living organisms. Insofar as we can see that these two thinkers analyzing the nature of spirit and physical force, where infinite species of possible beings live upon infinite space, there is a new view of the cosmos that is separate from a particular, homogenous dimension of spirit and matter. 25 Bruno sees God and infinity as both being the same as the ´infinite all´, a dimension in space where life is put into order in bodies that are animated by the soul. See, Bruno (1993): Dialogue I. 382-383, Dialogue II. 411-412, Dialogue III. 436. 26 The soul has a structure which produces cognitive states. For Bruno, the soul is chain of conscious states that extends from mnemonic recall to the contemplation of God. See, Farinella, A.; Preston, C., Giordano Bruno: Neoplatonism and the Wheel of Memory in the "De Umbris Idearum" 21 3.1 Space Flight and VTTM Copernican science-fiction involves a redefinition of humanity´s point of view as an intelligent species, and as a moving observer of space outside Earth. The issue of life on other planets invokes questioning the perspective of essentially belonging to one world, all the while being a visitor to other worlds. In VTTM, the main character of the story travels from the Earth to the Moon. If we travel to the Moon is it not an Earth? And looking at the Earth from the Moon does it not become a Moon? The greatest part of VTTM´s story of space flight suggests this common misconception is related to the mysterious nature of space outside Earth. The possibilities of heliocentric space characterize the representation of space flight outside Earth. The perspective of the sky-gazer who sees the Moon as a planet like Earth is bound by a spatial frame of reference27 from which the protagonist describes his journey outside Earth. The physical methods of propulsion the protagonist devises to leave Earth are clearly related to folk physic-like rules of thumb for projectile motion. These mix the effects of heat, vapor, and the displacement of mass into a bottle-rocket like jetpack, which the protagonist uses to reach the Moon; tying the vapor engines to his waist and flying upwards. The dynamic of heat and bottled water causes the vapor´s natural propellant properties to buoy himself skywards, working towards other heavenly spheres and new worlds. VTTM´s protagonist´s desired aim is to propel himself directly into the sky and towards the Moon´s and Sun´s astral position. He travels to the Sun, in the sequel to VTTM, using a seated space-vehicle; an icosahedron with planes of glass can amplify heat and rise into space. 27 A spatial frame of reference would not be the same as an ontology of vision that is describing the mechanics of space flight. To read about the ontology of vision in science-fiction see; Chen-Morris, Raz Shadows of Instruction: Optics and Classical Authorities in Kepler's ‘Somnium´. 22 Bergerac does not focus his idea of space flight on meteorological phenomena and its effect on space flight. Neither is the reality of space flight constricted by any limitation of the vapor-driven steam engine, which the protagonist uses to reach the new planets in VTTM. For him, space flight is the privilege of those with the knowledge to devise a working method of propulsion, and beside its evangelical value for space prophets, it is meant as a mechanistic feat of will. Favoring guesswork, curiosity, and adventurousness, the protagonist explores new worlds: ¨When I had, according to the computation I made since, advanced a good deal more than three quarters of the space that divided the Earth from the Moon; all of a sudden I fell with my Heels up and Head down, though I had made no Trip; and indeed, I had not been sensible of it, had not I felt my Head loaded under the weight of my Body: The truth is, I knew very well that I was not falling again towards our World; for though I found myself to be betwixt two Moons, and easily observed, that the nearer I drew to the one, the farther I removed from the other¨ (Bergerac, VTTM, (1687): p. 21) Instead of floating endlessly after leaving Earth, without anything to interrupt a free fall, as he approaches the surface of the Moon the protagonist’s perspective is inverted to perceive a new spatial frame of reference. The inversion in perspective is accompanied by a realization of the falsehood of a mere bodily sensation that asserts ‘up’ and ‘down’, mere conventions, which do not apply to the spatial sense of an astronaut exploring new planets. There is a relative frame of reference for projectile motion, between Earth and the Moon, which the astronaut experiences. Thus, the protagonist is not able to describe a true point of reference as he moves in space, moving away, or toward, a relative point in space, while approaching a new heavenly body. The new planet described in VTTM, as much as it is to do with embodying human spirit theories like a Galilean 23 viewpoint of relative motion, has also to do with the possibilities of establishing a new measuring point for human consciousness; a moving satellite´s vision of the cosmos in a new world outside Earth. We will see in the next sections how the discovery of a new world is a rich avenue of exploration for early modern renaissance culture. The tradition of human optimism28 encapsulates what we will be tracing in the possibilities of science-fiction literature. Cyrano borrows from the tradition of older pre-Copernican science. Human beings explore physical objects in VTTM, and identify the fundamental relationships to other material and spiritual bodies, and discovering spatial regions that exist as a result of what is and what is not possible, in the context of astronomy, and pseudoastronautic technology. The frame of reference for the relations between physical bodies that we see in VTTM, and its sequel, is not based in an actual empirical context of aerodynamics, but is based more so in the interactions between heat and all physical classes of matter, throughout an interplanetary spatial realm. The ballistics and rocketry techniques necessary for space travel imply a higher knowledge of propellants, like gunpowder or cordite, had not yet become a coherent scientific activity in Bergerac´s day29. By reaching a new planet outside Earth and discovering a new world, Bergerac´s astronaut has crossed the threshold between one world and another. By describing the exploration of a new world in a heliocentric worldview Bergerac has himself symbolized the human aspiration towards the 28 The 17th century philosopher Leibniz speaks of metaphysical optimism by stating that humanity inhabits ¨the best of all possible worlds¨. The principle of a pre-established harmony of all existences and laws in nature explains this proposition. Immanuel Kant refers to the same by affirming the existence of two or more equally perfect worlds. 29 Aeronautics was not an established area of research until the 19 th century. In 1908 the Wright Brothers achieved air flight. Space travel was inaugurated by Sputnik, a Russian space satellite, in 1957. Rocket technology has its beginnings in German, American, Russian scientific societies. See, Pendray, G. Pioneer Rocket Development in the United States. 24 unknown. The idealized juncture of heat and projectile motion is his way of developing the idea of space flight and presenting the discovery of new worlds as a feature of astronautic culture that is part of a Copernican paradigm shift. Next, we will be looking into in the thought of renaissance philosopher Pico della Mirandola that is considering human nature as it is ultimately characterized by new possibilities that humanity explores. 3.2 Science-Fiction Optimism Natural science and space technology in Bergerac´s fictional narration represents the experimental discovery of intelligent organisms outside Earth. Whereas before angels, gods, and other spirits would exist in higher realms of thought and space, now the human astronaut in VTTM inhabits interplanetary space and explores the possibilities of new worlds. With Bergerac’s sciencefiction narration, a modern science-fiction worldview, we see how western culture seeks the idea of new worlds, to describe the irremediable value of the human will in modernity, a new human optimism, which makes it possible to imagine humans discovering new spatial regions. The 15th century eclectic philosopher Pico della Mirandola refers to an argument relating to the cosmological worldview of human optimism in his Oration on the Dignity of Man. Using Kabbalistic imagery, and concepts that correspond to mystical practice, Pico explains why the human species exists in a hierarchy of living beings, where angels remain above humankind, and beasts are inferior to the human species. In a sense, humanity´s place in the great chain of being, from Mirandola´s perspective, is proof of the highest bestowal of grace for the human species, which God can manifest as a miracle of divine will in nature (Mirandola, (1956): p. 4-5). Humanity exists in the middle of creation, at a central referential point that can be seen by restoring confidence in humanity. The knowledge of 25 human optimism lies beyond the brutality of human existence, which is characteristic of lower animal consciousness, and is therefore redeemed by divine grace, which leads to a calling for humanity to rise, from obscurity into clarity. The idea of a human body, as it is understood according to the possibility of space travel, recalls the great chain of being30 where life and death are a possibility for conscious beings that possess knowledge of a true reality. The human imagination is to be discovered as new knowledge. Mirandola´s humanist conception of knowledge muses on the necessary aspects for humanity to exist, in a purely spiritual heaven or hell. The state of humankind´s spirit, as a species, exists between these two opposites without exception, in a perpetual motion of knowing and unknowing. The focus of the human species in the continuum of nature is a result of human optimism, an urge to explore nature, and to reveal human knowledge through feats of exploration. The tradition of astronautics, which culminates with such achievements as the moonshot, the Hubble telescope, and the International Space Station, reflects human optimism and knowledge. Human values consider the perspective of humanity´s new place in the cosmos and in the great chain of being, and echo the discovery of new regions of space outside Earth. Under this perspective, the true proportions of human optimism are made possible by affirming that new realms outside Earth can be reached using technology, as it may be understood by human space travelers. 30 Mirandola refers to the ´ladder of being´, in reference to the story of Jacob´s ladder in the Bible, around which heaven and Earth are unified: ¨´We have given you, O Adam, no visage proper to yourself, nor endowment properly your own, in order that whatever place, whatever form, whatever gifts you may, with premeditation, select, these same you may have and possess through your own judgement and decision… I have placed you at the very center of the world, so that from that vantage point you may with greater ease glance round about you on all that the world contains.¨ (Mirandola, (1956): p. 7). 26 We had seen that the Earth´s surface serves as an epicenter of physical and spiritual matter in pre-Copernican culture. Heliocentrism is a necessary aspect of a more precise knowledge of the cosmos that is reflected in early modern science-fiction and which characterizes the meaning and value of the condition of scientific discovery, identifying the character of human optimism in a technological space age. The role of the astronaut in modern culture is representative of a worldview that is given in science-fiction, which comments on the possibilities of astronautic journeys. 3.3 Human Intelligence and Alien Species For the protagonist exploring planets outside Earth31, using rudimentary folk-physics, it is actually possible to discover new forms of life existing in new worlds, on the Sun and Moon. The natural advantage that alien species have over humankind, by virtue of their living outside Earth, and by their place on the hierarchy of spiritual, intelligent species, presents an interesting twist to the protagonist´s space travels. The Copernican status of Bergerac´s novels express a conjecture: if life exists on planets outside Earth, then Earth is not fit to support life; Earth is not a planet that has an environment fit for lifeforms that are more advanced technologically than humans. This quandary leads the reader of VTTM to think the human species as one among countless other species of existent beings on the Moon, and Sun. One of the recurring themes of the protagonist’s narrative deals with the mystification produced by the human body and mind, from the aliens´ perspective. This issue is coupled with the protagonist’s incredulity in accepting that the Moon is a world, and that the Earth is now a Moon. Subsequently, the protagonist is now an alien who is unaware of what type of creature he really is. 31 Exo-planets are planets other than Earth where life can be sustained, which are defined by a system of classification. See; Marcy, Geoffrey W. Other Earths and the Search for Life in the Universe. / 27 There is a prevailing theme wherein the protagonist´s capacity for reason is doubted until a certain alien comes to advocate on behalf of this waylaid earthman, in front of the disbelieving alien hosts. The question of humanity´s place in the cosmos is no longer an astronomical problem solved by using theories. Humans have become aliens to species from another planet. In VTTM, the aliens want to know if the human organism does, or does not have a rational mind. The alien who helps him with the problems he encounters, regarding the veracity of his biological human form, has gone to Greece on Earth, and was called the daemon of Socrates. This alien also happens to be the same one who appeared to Cardanus, the philosopher who informed the protagonist of the existence of life outside Earth. This character is one of the few aliens on the Moon who knows that the protagonist is fit to reason; since he has previously traveled to Earth and communicated with humans. He is actually an alien from the Sun, in disguise, sent to live on the Moon due to overpopulation on the Sun´s worlds. Bergerac´s heliocentric cosmology points to the likelihood, from the perspective of Copernicanism32, for discovering new forms of intelligence in other parts of the cosmos. The urge to devise technologies is the same as the point of view of a human body and mind exploring the rest of the cosmos. Aliens that are conscious have a view born from their own experimental science and natural philosophy. The natural philosophy of the Lunar and Solar species is registered in the eternal transformations of living and inert matter, occurring beyond the animal body of earthbound creatures, and resulting in the form of a first matter, which can be understood in the following way: ¨For that Eternity which they deny the World, because they cannot comprehend it, they attribute it to God, as if he stood in need of that Present, and as if it were 32 Exo-biology treats the question asking if life is limited to our planet or if it is not. See: Levin, G. Significance and Status of Exobiology. 28 easier to imagine it in the one than in the other; for tell me, pray, was it ever yet conceived in Nature, how Something can be made of Nothing? Alas! Betwixt Nothing and an Atome only, there are such infinite Disproportions, that the sharpest Wit could never dive into them; therefore to get out of this inextricable Labyrinth, you must admit of a Matter Eternal with God…¨ (Bergerac, VTTM, (1687): p. 108) The reality of inhabited planets outside Earth can be understood in VTTM as a faculty of created matter, a matter that arises out of nothingness and can give form to an infinite amount of possible beings. Just as the creative instinct of God creates all things in an infinite universe that has no cause, there can be an infinity of possible beings. The difficulty of understanding Bergerac´s natural philosophy refers plainly to the problem of a heliocentric cosmology, as it is altering the view of what matter does, and where, physically, in the cosmos composed of the finite dimensions arising from physical space. Physical space is derived by way of the individual form of atoms and their motions that account for the existence of the physical world, its multiple forms to appear in. A physical world can´t come from nothing, it must have a cause or a physical force. The effect of any atom upon cosmic matter, as such, conditionally arises in nothingness, by physical force alone. Space is seen from a materialist perspective, which understands first matter and atoms as properties of nature, as atoms compose the bodies of all organisms, and their organic processes (Bergerac, VTTM, (1687): p. 107117). An infinite force can´t be constructed, nor perceived by a single observer independently, nor from the perspective of a finite spatial sense. VTTM is alluding to is a principle for nature to 29 dispose matter that may have some function delineated through creative properties that organize atomic bodies in space: ¨If Art then be capable of inclining a Body to a perpetual Motion, why may we not believe that Nature can do it? It's the same with the other Figures, of which the Square requires a perpetual Rest, others an oblique Motion, others a half Motion, as Trepidation; and the Round, whose Nature is to move ¨ (Bergerac, VTTM, (1687): p. 109) Bergerac is not a metaphysician of the realist, reductivist atomist worldview. He takes from the Neoplatonic tradition that speaks of the union of life to matter, depicting the perfection of innate physical forces joining soul and body. This is related to the idea or notion of Earth´s qualities, outside of its image as a fixed center in space, is an attribute of infinite animal consciousness (Bergerac, VTTM, (1687): p. 100). Whereas Bergerac´s science fiction is a modern take on space exploration, we can still find elements in his work that are throwbacks to the Aristotelian and Platonic division of sub-lunar and super-lunar realms, and pre-Copernican natural philosophy. In VTTM, the role of nature in assigning form to tangible objects corresponds to the possibilities of first matter outside Earth33, as is evident everywhere in atoms retaining mass throughout the cosmos. Thus, the Moon and Sun aliens are the only ones that can show human consciousness cosmic creativity in an infinite universe replete with atomic bodies, as it is understood to exist by conscious organisms. 33 In one part of the story a Solar alien illuminates a room with trapped sunlight. ¨I have fixed their Light, and inclosed it within these transparent Bowls. That ought not to afford you any great Cause of Admiration; for it is not harder for me, who am a Native of the Sun, to condense his Beams, which are the Dust of that World, than it is for you to gather the Atomes of the pulveriz'd Earth of this World.¨ (Bergerac, VTTM, (1687): p. 118-119) 30 The creative consciousness of matter, as a principle of nature, is at any rate an example of early modern panpsychism34, a thesis that claims to demonstrate physical matter arises from incorporeal consciousness. The perfection of heliocentric space implies the perfection of those things that exist within a heliocentric cosmos, such as a plenum and vacuum, in every possible configuration of matter. The phenomena of interplanetary space exploration in Copernican science-fiction are used in VTTM to review what humanity knows about the cosmos where physical matter outside Earth35 exists, and extra-terrestrial consciousness is discovered. The alien´s natural science in VTTM is proof of the creation of new life outside Earth. The protagonist’s posture as a science-fiction natural philosopher and astronaut reflects the human body´s performance in new spatial and spiritual realms outside Earth, exploiting the knowledge given to him through the example of space travel and technology. In VTTM, the argument of first matter is clearly observed by alien species who originate outside Earth, who can understand the physical changes of this substantial process as it creates life inside an interplanetary cosmos, understood more clearly by aliens than by humans. Conclusion The Copernican astronomical and cultural frame of reference, in early modern science-fiction, is derived from the character of natural science in literature36. It claims that it is possible to imagine life outside Earth; as well as making it possible to imagine a method of rocket propulsion. In the 34 Thales of Mileto, pre-Socratic philosopher, believed that motion was tied to the soul´s effect on matter. Panpsychism is a problem related to the contemplation of matter and the existence of divinity. See; Skrbina, David Panpsychism in the West. 35 In a scene of the sequel to VTTM, the protagonist is floating out of the planetary system into the vacuum of space at the limit of the sphere of the fixed stars; crossing the celestial firmament his body loses its color and becomes translucent. When the protagonist returns into the planetary sphere, by willing himself towards the solar center, he regains his usual bodily form. (Bergerac, C., Comical History of the States and Empires of the Sun (1687): p. 76-86) 36 Science-fiction literature involves a relationship between the unknowable, and a novel scientific idea, which centers the narrative from an expected dramatic resolution, on a cognitive plane. See; Suvin, Darko Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre. 31 early period of renaissance humanistic culture, freethinkers like Cyrano de Bergerac create new, interrelated cultural products of the new discoveries in astronomy, natural philosophy, and cosmology. Cyrano de Bergerac´s works retain European renaissance cultural view, referring to new possibilities that give birth to modern science-fiction. Additionally, a work like Bergerac´s expresses the possibility of culture that corresponds to a new vision of space inspired from speculation of a new solar center. For this work different philosophers and scientists have been reviewed and commented on to discern the cultural juncture between ancient astronomical thought, and early modern sciencefiction. Ptolemy’s geocentric astronomy, alongside the technical tools used in astrology and horoscopy, show us how there is a cultural view that is related to the reflection on humanity´s spatial sense, identifying the idea of ourselves as earthbound creatures. We have also reviewed Copernicus’s restructuring of mathematical-astronomy, which relates to discoveries in space, in a sense of exposing a relationship between humanism and astronomy. Giordano Bruno´s thesis of an infinite universe is derived from the idea of physical atoms that are part of innumerable worlds, where life is possible in outer space. The cultural model of European humanism implies a sense of the importance of scientific discovery. Copernicanism produces a culture of scientific speculation that is relevant to the moment of origination of science-fiction literature. A new, humanistic vision of the cosmos, which is an inherent part of science-fiction´s depiction of technological innovation, as such, is ambiguously tied up in the possibility of pre-Copernican techniques of astrology and star gazing. A new perception of natural science in VTTM is restructured round the value of human humility, characterizing a new, meaningful posture for a Copernican cultural paradigm that includes the idea of life outside Earth, and the possibility of alien consciousness outside Earth. 32 A Copernican cultural paradigm begins, as an epistemological worldview, with a theoretical feature of the spatial perception of space; the Earth is orbiting the Sun; the vastness of space is so great that humanity must reimagine the nature of bodily experience. The technological space age involves references to postures that are antique, but are reflecting the leadership of Copernicanism in early modern humanism. A new sense of humility, inspired by the discovery of aliens in VTTM, complements the Copernican optimism of an astronautic age. The mixture of Aristotelian and Platonic doctrines that represent Bergerac’s story of aliens outside Earth, quite similarly to Mirandola’s concept of a “ladder of being”. These doctrines are mixed in with the Copernican elements, in VTTM, as a version of science-fiction optimism brought into existence during the renaissance. Astronautic themes are reminiscent of the urge to exploration and discovery has been inquired in this text, relating space travel and technology to paradigm shifts found in modern culture; the climate of human optimism, and human humility, in early modern science-fiction. The change between Ptolemaic and Copernican approaches to astronomical measurement contributes to the discussion of cultural artefacts and their relation to knowledge, beyond technical discussions of astronomical models. The privileged perspective of seeing Earth in space, of seeing Earth as a planetary body, is a perspective from which humans typically assert their physical bodily perception and everyday existence. Earth is no longer a sui generis37 object, but is now a planet with certain natural properties that can be measured, uniformly, in theories that refer to the Earth as a planet, supporting living beings that are made up from atoms. 37 In a geocentric, Ptolemaic world system, Earth is a unique object that is not a planet, and thus, is the only place for life to exist. See; Bula, G. (2011): p. 136. 33 The combination of cutting edge scientific and mythological views on the existence of life in the cosmos is a pertinent feature of the early modern science-fiction that speaks to the development of Bergerac´s unique, hybrid vision of cultural Copernicanism. Early modern science-fiction is an example of a mixed view of human history made up from views of a cyclical, eternal recurrence of nature in older pre-Copernican cultures, and which aspires to an image of progress, where there are innovative technological efforts, exploring new, distant locales away from Earth. The aesthetics of early modern science-fiction suggest that technical innovations can be brought to bear on complex viewpoints that can be expressed in cultural products. Bibliography 1. Dear, Peter What is the History of Science the History of? Early Modern Roots of the Ideology of Modern Science (2005) Isis, 96(3), p. 390-406. 2. Galilei, Galileo Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (1632) Trans. Stillman Drake Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1953) Berkeley: University of California Press. 3. Bergerac, Cyrano L’Autre monde ou les états et empires de la Lune (1657) Histoire comique des états et empires du soleil (1662) Trans. Archibald Lovell, Comical History of the States and Empires of the Worlds of the Moon and Sun (1687) London: Printed for Henry Rhodes, Voyage to the Moon (1889) New York: Doubleday and Mcclure Co. 4. Riley, Mark Theoretical and Practical Astrology: Ptolemy and his Colleagues, (1987) Transactions of the American Philological Association, 117, p. 235-256. 5. Tester, Jim A History of Western Astrology (1987) Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer. 6. Ptolemy Mathēmatikē Syntaxis (2nd century C.E.) Tran. G.J Toomer, Almagest (1984) London: Duckworth. 34 7. Wright, M.T. Greek and Roman Portable Sundials: An Ancient Essay in Approximation (2000) Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 55(2) p. 177-187. 8. Couprie, Dirk L. The Qumran Rounder and the mrhyt: A Comparative Approach (2013) Dead Sea Discoveries, 20(2) p. 264-306. 9. Ptolemy Apotelesmatiká (2nd century C.E.) Trans. J.M Ashmand Tetrabiblos (1882) London: Davis and Dickson. 10. Washburn, Alan R. Orbital Dynamics for the Compleat Idiot (1999) Naval War College Review, 52, p. 120-129. 11. Kuhn, T. S. The Copernican Revolution. Planetary Astronomy and the Development of Western Thought (1957) Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 12. Kuhn, T. S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 13. Aristotle, peri uranú (4th century B.C.E) Trans. J.L Stocks, On the Heavens (1922) Oxford: Clarendon Press. 14. Aristotle ta meta ta physika (4th century B.C.E) Trans. W.D Ross Metaphysics (1924) Oxford: Clarendon Press. 15. Aristotle peri geneseôs kai phthoras (4th century B.C.E) Trans. H. H. Joachim (1926) On Generation and Corruption Oxford: Clarendon Press. 16. Copernicus, N. De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (1543) Trans. Charles Glenn Wallis (1939) Annapolis: St. John´s Bookstore, On the Shoulders of Giants: The Great Works of Physics and Astronomy (2002) p. 1-388. 17. Lakatos, Imre; Zahar, Elie Why did Copernicus´s Research Program Supersede Ptolemy´s The Copernican Achievement (1975) Los Angeles: University of California Press, p. 354-384. 18. Rosen, Edward Copernicus and his Successors (1995) London: The Hambledon Press. 35 19. Swerdlow, Noel M. Hipparchus's Determination of the Length of the Tropical Year and the Rate of Precession (1980) Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 21(4), p. 291-309. 20. Neugebauer, O. The Alleged Babylonian Discovery of the Precession of the Equinoxes (1950) Journal of the American Oriental Society, 70(1), p. 1-8. 21. Ernest S.; Kennel, Charles F. The Role of Error in Ancient Methods for Determining the Solar Distance, (1975) The Copernican Achievement, Los Angeles: University of California Press, p. 130-137. 22. Knox, Dilwyn Copernicus´s s Doctrine of Gravity and the Natural Circular Motion of the Elements (2005) Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 68, p. 157-21. 23. Hanson, Norwood Russell The Copernican Disturbance and the Keplerian Revolution (1961) Journal of the History of Ideas 22(2), p. 169–184. 24. Gearhart, C.A Epicycles, Eccentrics, and Ellipses: The Predictive Capabilities of Copernican Planetary Models (1985) Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 32(3/4), p. 207-222. 25. Bruno. G. De l'infinito, universo e mondi (1584) Trans. Miguel A. Granada, Del Infinito Universo y los Mundos (1993) Madrid: Alianza Editorial. 26. McMullin, E. Bruno and Copernicus (1987) Isis, 78(1), p. 55-74. 27. Farinella, A.; Preston, C., Giordano Bruno: Neoplatonism and the Wheel of Memory in the "De Umbris Idearum" (2002) Renaissance Quarterly, 55(2), p. 596-624. 28. Chen-Morris, Raz Shadows of Instruction: Optics and Classical Authorities in Kepler's ‘Somnium´ (2005) Journal of the History of Ideas, 66 (2), p. 223-243. 29. Pendray, G. Pioneer Rocket Development in the United States (1963) Technology and Culture, 4(4), p. 384-392. 36 30. Mirandola, Pico Della, De hominis dignitate (1486), Trans. Robert A. Caponigri, Oration on the Dignity of Man, (1956) Chicago: Regnery Publishing. 31. Marcy, Geoffrey W., Other Earths and the Search for Life in the Universe (2010) Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 154(4), p. 422-438. 32. Levin, G. Significance and Status of Exobiology (1965) BioScience, 15(1), p. 17-20. 33. Skrbina, David Panpsychism in the West (2005) Cambridge: MIT Press. 34. Suvin, Darko Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre (1979) New Haven: Yale University Press. 35. Bula, G. Cosmotheoros: Spiritual Corollaries to the Rare Earth Solution to Fermi´s Paradox (2011) The Trumpeter, 27 (3), p. 123-146. 36. Van Brummelen, G. Taking Latitude with Ptolemy: Jamshīd al-Kāshī's Novel Geometric Model of the Motions of the Inferior Planets (2006) Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 60(4), 353-377. 37. Geertz, Clifford The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays (1973) New York: Basic Books Inc. 38. Capra, F., Luisi, P. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision (2014) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 39. Obrist, B. THE PHYSICAL AND THE SPIRITUAL UNIVERSE: "INFERNUS" AND PARADISE IN MEDIEVAL COSMOGRAPHY AND ITS VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS (SEVENTH-FOURTEENTH CENTURY) (2015) Studies in Iconography, 36, p. 41-78. 37