AKMY - 6e - ch11 - SM - 百度文库

百度文库

搜索文档或关键词

普通分享 >

AKMY_6e_ch11_SM

共享文档

2015-02-12

56页

用App免费查看

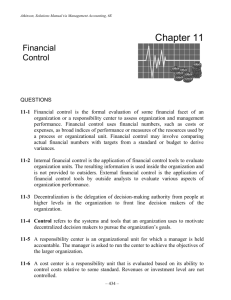

Chapter 11

Financial

Control

QUESTIONS

11-1 Financial control is the formal evaluation of some financial facet of an organization or a

responsibility center to assess organization and management performance. Financial control

uses financial numbers, such as costs or expenses, as broad indices of performance or

measures of the resources used by a process or organizational unit. Financial control may

involve comparing actual financial numbers with targets from a standard or budget to derive

variances.

11-2 Internal financial control is the application of financial control tools to evaluate

organization units. The resulting information is used inside the organization and is not

provided to outsiders. External financial control is the application of financial control tools by

outside analysts to evaluate various aspects of organization performance.

11-3 Decentralization is the delegation of decision-making authority from people at higher

levels in the organization to front line decision makers of the organization.

11-4 Control refers to the systems and tools that an organization uses to motivate

decentralized decision makers to pursue the organization’s goals.

11-5 A responsibility center is an organizational unit for which a manager is held accountable.

The manager is asked to run the center to achieve the objectives of the larger organization.

11-6 A cost center is a responsibility unit that is evaluated based on its ability to control costs

relative to some standard. Revenues or investment level are not controlled.

11-7 A revenue center is assigned the responsibility to achieve, within its own operating

guidelines, a target level of revenues. Managers in a revenue center do not control costs or the

level of investment.

11-8 Organizations use profit centers when profit center employees have the ability and

responsibility to control significant levels of revenues and costs of the products or services

they deliver.

11-9 An investment center is a responsibility unit that is evaluated based on its return on

investment. The managers and other employees control revenues, costs, and the level of

investment.

11-10 The controllability principle requires that people should only be held accountable for

results that they can control. The manager of a responsibility center should be assigned

responsibility for the revenues, costs, or investments controlled by responsibility center

personnel.

11-11 Responsibility centers participate in developing the goods and services that the

organization supplies to its customers, sharing the use of many common resources in this

process. In most organizations, many revenues and costs are jointly earned or incurred.

11-12 A segment margin is the difference between the revenues and costs that are deemed to

be directly controllable by a responsibility center. It is therefore an important summary

performance measure for each responsibility center.

11-13 A soft number is a number that is based on conventional accounting assumptions but

relies on subjective revenue and cost allocation assumptions over which there can be

legitimate disagreement. Because soft numbers result from subjective interpretation, they are

neither right nor wrong.

11-14 A transfer price is the price at which a good or service is deemed to have been

transferred between two responsibility centers within an organization. The transfer price is

treated as revenue in the supplying division and as a cost in the receiving division. The

transfer price is a fiction created for control purposes and does not affect external reporting.

11-15 The four bases for setting transfer prices are market, cost, negotiated, and

administered.

11-16 Organizations earn revenues by selling goods and services to customers. When

organizations use control systems that require revenue numbers for responsibility centers, the

revenue earned from the sale to the final customer must be divided among the contributing

responsibility centers. This process is necessary to prepare responsibility center income

statements, and in turn, evaluate the center’s performance.

11-17 Organizations use many types of resources to make goods and services. When

organizations use control systems that require cost numbers for responsibility centers, the

costs of the resources that are used by two or more responsibility centers must be divided

between or among those responsibility centers. This process is necessary to prepare

responsibility center income statements, and in turn, evaluate the center’s performance.

11-18 Return on investment is a measure of accounting income (typically, operating income)

divided by a measure of the investment in the assets used to earn that income.

11-19 All other things being equal, as efficiency (the ratio of income to sales) increases

(decreases), return on investment increases (decreases).

11-20 All other things being equal, as productivity (the ratio of sales to investment) increases

(decreases), return on investment increases (decreases).

11-21 Residual income is the difference between reported accounting income and the

required return on the investment (economic cost of investment) used to earn that income.

11-22 Economic value added (EVA) is a refinement of the residual income idea. The EVA

computation adjusts reported accounting income and asset levels for what many consider the

biasing effects on current results of the financial accounting doctrine of conservatism. For

example, GAAP requires the immediate expensing of research and development costs; yet,

when shareholder value analysis income is computed, research and development costs are

capitalized and expensed over a certain time period, such as five years.

11-23 Whole Foods states, “ We use EVA extensively for capital investment decisions,

including evaluating new store real estate decisions and store remodeling proposals. We only

invest in projects that we believe will add long-term value to the Company. The EVA decisionmaking model also enhances operating decisions in stores. Our emphasis is on EVA

improvement …”

( http://www.wholefoodsmarket.com/company/eva.php, accessed January 12, 2011) . As

mentioned in Chapter 11, Quaker Foods & Beverages, a food manufacturer, used EVA to

support its decision in June 1992 to cease trade loading , which is the food industry’s practice

of using promotions to obtain orders for a two- or three-month supply of food from customers.

Trade loading causes quarterly peaks in production and sales that, in turn, require huge

investments in assets, including the inventory itself, warehouses, and distribution centers.

11-24 Financial control alone may be an ineffective control scorecard for three reasons. First,

it focuses on financial measures that do not measure the organization’s other important

attributes, such as product quality and customer service. Second, financial control measures

the financial effect of the overall level of performance achieved on the critical success factors,

and it ignores the performance achieved on the individual critical success factors. Third,

financial control is usually oriented to short-term profit performance.

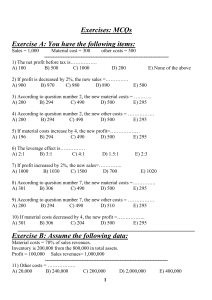

EXERCISES

11-25 Decentralization creates the need to ensure that the decentralized decision makers are

pursuing the organization’s stated goals and are coordinated as they make their independent

decisions.

11-26 Examples of organization units that might be responsibility centers in a university

include: A school or college, a department within a school or college, maintenance, the

computing center, a dormitory residence, the registrar’s office, a sports program, and the

alumni office.

11-27 Examples of cost centers are: A maintenance department in a factory, a computer

department in an insurance company, and a personnel office in a government. What these

responsibility centers have in common is that they do not deal directly with the organization’s

primary customer. Therefore, they have no direct effect on revenues. They also do not control

investment levels.

11-28 Examples of revenue centers are: The sporting goods department in a large department

store where the corporation’s purchasing group makes all stocking decisions, the counter

department in a fast food restaurant, and the sales office in an insurance company. What these

responsibility centers have in common is that they all deal with customers and have little

control over the major cost of the product that they are selling to the customer. They also do

not control investment levels.

11-29 The manager of a large department store may have little control over stock, prices, and

advertising but controls many of the other facets of performance. How customers are treated

and how displays are arranged will affect sales. How staffing is done and service functions

performed within the store will affect its total costs. However, the main determinants of

investment—building costs and inventory, are likely not controllable by the manager.

Therefore, it is likely that the store should be evaluated as a profit center rather than as an

investment center. The maintenance department is likely to meet the conditions of a cost

center—it sells nothing to outside customers and only has a vague and indeterminable effect

on sales. A single department within a store is likely to be treated as a revenue center since the

manager of that department is likely to have a minimal effect on the department’s costs.

11-30 Although many people assume that a foreign subsidiary will meet the conditions to be

treated as an investment center, the classification is not automatic. As with divisions within a

company, the key is the discretion that the subsidiary’s management has over prices, product

selection, product development, costs, and investment levels.

11-31 Responsibility centers might include cooking operations, ordering operations, counter

and customer service operations, and maintenance. All responsibility centers interact in terms

of providing customers with low costs, quality, and service.

11-32 The manager of the cinema does not control the movie that is playing, the advertising

that is done for the movie, the cost of the products sold at the snack bar (these would likely be

purchased by a central agency, which would also make the decision about what products to

sell), and the wages that are paid to employees (this would likely be determined by a collective

agreement between the union representing all the employees at all the cinemas and the parent

company). The manager and her staff would control how customers are treated (which might

affect revenues), the scheduling of staff (which would affect total staff costs and service), the

amount of waste and pilferage in the snack bar, and the organization of ticket and snack bar

sales (which might affect total sales).

11-33 There are two generic problems in this setting. Are the revenues reported for this

division independent of the revenues reported for the other divisions? For example: Are there

interactions that require transfer pricing or do sales in renovations affect sales in other

departments? If these interactions exist, it is difficult to interpret the revenue, and therefore

the profits, reported by each division as the contribution by that division to corporate profits.

Similarly, if there are cost interactions (for example, the divisions use the same expensive

equipment and cost allocations are used to assign the cost of that equipment to the divisions)

then it is difficult to interpret the costs reported for a division, and therefore its profits, with

any certainty.

11-34 The response to this question will reflect the degree of autonomy the respondent feels

that the center manager has. It is likely that the fitness center manager must follow head office

policy concerning the wages paid, but the center manager will control the number of hours

worked by casual employees. If the chain’s policy is to build identical buildings with identical

equipment, then the depreciation on the building and equipment is not controllable by the

center manager.

The manager should be held accountable for controllable costs and should not be held

accountable for costs that (1) were determined or incurred by someone else and (2) cannot be

changed. The reason for distinguishing between controllable and uncontrollable costs is to

identify which costs the manager should be held accountable for. The controllability principle

asserts that the manager should only be held accountable for controllable costs.

11-35 The controllability principle asserts that the manager of a responsibility center should

be assigned responsibility only for the revenues, costs, or investments controlled by

responsibility center personnel. Revenues, costs and investments that people outside the

responsibility center control should be excluded from the accounting assessment of that

center’s performance. For example the manager of a production line in a factory should be

evaluated based on labor and machine hours used and not on labor cost and machine cost

because labor wage rates and machine costs were determined elsewhere in the organization.

In this case, invoking the controllability principle will have a desirable effect if the manager

perceives the performance measurement process as fairer, thereby increasing his or her

satisfaction.

Suspending the controllability principle is desirable if there is a reasonable expectation that

this will cause the employee to find a means of controlling the previously uncontrollable event

and that the employee will feel that being asked to control the event is reasonable. For

example, as described in the textbook, a dairy faced the problem of developing performance

standards in an environment of continuously rising costs. Because the costs of raw materials,

which were between 60% and 90% of the final costs of the various products, were market

determined and, therefore, thought to be beyond the control of the various product managers,

people argued that evaluation of the managers should depend on their ability to control the

quantity of raw materials used rather than the cost.

The dairy’s senior management announced, however, that it planned to evaluate managers on

their ability to control total costs. The managers quickly discovered that one way to control

raw materials costs was to make judicious use of long-term fixed price contracts for raw

materials. These contracts soon led to declining raw materials costs. Moreover, the company

could project product costs several quarters into the future, thereby achieving lower costs and

stability in planning and product pricing.

Thus, managers, even when they cannot control costs entirely, can take steps to influence final

product costs. When more costs or even revenues are included in performance measures,

managers are more motivated to find actions that can influence incurred costs or generated

revenues.

11-36 Division C has sufficient excess capacity to supply the 200,000 units of C82 to Division

D, so neither Division C nor McCann Company will incur an opportunity cost if the transfer

takes place. The incremental cost for Division C to manufacture the C82 for Division D is

200,000 × ($20 + $12 + $8) = $8,000,000. If Division D purchases these units from the outside

market, it will spend 200,000 × $50 = $10,000,000 and both Division D and the McCann

Company will be $2,000,000 (= $8,000,000 − $10,000,000) worse off. For Division C, the

transfer price should at least cover variable costs of $40. For Division D, the transfer price

should be less than $50. So to induce an internal transfer, the transfer price should be between

$40 and $50.

11-37 When transfer prices are used for internal purposes they are generally intended to

motivate the decision maker to act in the organization’s interest. However, when transfer

prices are used for international transfer pricing, managers have an incentive to choose

transfer prices to minimize the organization’s total tax liability by locating most of its profit in

the lower-tax country. The objectives for internal purposes and international tax purposes are

often conflicting. Tax authorities are well aware of the tax incentives, and therefore examine

international transfer pricing policies of companies conducting business under the authorities’

jurisdiction. The 1995 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

guidelines (Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations

(Paris: OECD, 1995)) indicate that whenever possible, transfer prices should reflect market or

economic circumstances. If an organization’s domestic transfer pricing system has been

designed to reflect economic considerations, then its international transfer pricing system

should be the same. Moreover, using one system for domestic transfer pricing and a different

system for international transfer pricing is likely to trigger investigation by taxing authorities.

11-38 Transfer prices can be based on market prices, based on costs, negotiated, or set by

some arbitrator or administrative rule. There are market prices for raw logs. However, the

number of logs that this company buys in these markets would likely be small compared to the

number of logs that are processed internally. The transfer price could be based on the costs of

maintaining the forests and logging costs. However, logs suitable for a sawmill are more

valuable than logs suitable for a pulp mill, and cost-based transfer pricing would not reflect

this. If a reliable market price is available, it can be used as the transfer price.

The real issue here is the benefit to the organization of treating the logging and

finishing divisions (the saw mills and the pulp mills) as profit centers. If company

success is determined by having the appropriate supply of trees at the

appropriate time, those criteria might be a more useful basis for control than

financial controls organized around profit centers.

11-39 Assuming that the finished products are prepared especially for this fishing products

company, there are likely limited market prices for raw fish and semi-processed fish, but little

outside market opportunity to sell finished products. Therefore, while transfers between

harvesting and processing might be based on market prices or costs, transfers between

processing and selling would have to be based on costs. One approach used by a fishing

company in this situation is a dual pricing system where the selling division is paid the net

realizable value of the product and pays the accumulated cost to date. Another fishing

company in this situation treats each unit as a cost center and evaluates the contribution that

each unit makes to product quality and timeliness of product availability.

11-40 A market price is an independent valuation of the transferred good or service.

Therefore, the market price is an excellent way of identifying where value is added in the

organization. However, finding the exact market price of the transferred product may be

difficult because the market price will often reflect many product facets that may not be

identically replicated in the product being transferred. In order to use a market price the

organization must ensure that the transferred product is exactly the same as the product for

which a market price is observed.

11-41 Numbers that accountants report to outsiders in financial statements are hard in the

sense that they result from the application of strict rules . In a given situation, there is some,

but limited, opportunity for discretion in determining a number’s value. Therefore, people

tend to think of accounting numbers as hard in the sense that two accountants faced with the

same situation would likely come up with numbers that are quite close together. For internal

financial control, however, many accounting numbers, such as profits and costs, result from

applying subjective rules such as transfer prices and cost allocations. These subjective rules

create the possibility of large differences resulting from the application of different

assumptions. The idea of a soft number was likely developed to warn people that these

internal accounting numbers have very different properties than the accounting numbers that

are reported to outsiders.

11- 4 2 One possibility is to assign building costs to the departments based on the floor space

that each occupies, on the assumption that the building size is the cost driver for building

costs.

11-43 (a) Return on investment is division income divided by historical cost of investments,

and residual income is division income minus 10% of historical cost of investments.

Division Historical

Division

Return on Investment

Residual Income

Cost of Investments

Operating Income

X

$560,000

$66,500

11.88%

$10,500

Y

532,000

64,400

12.11%

11,200

Z

350,000

43,120

12.32%

8,120

(b)

Division Net Book Value of

Investments

Division

Return on

Investment

Residual

Income

X

$280,000

$66,500

23.75%

$38,500

Y

266,000

64,400

24.21%

37,800

Z

175,000

43,120

24.64%

25,620

Operating

Income

(c) Return on investment and residual income do not necessarily produce the same rankings,

as seen in part (a), where Division Z has the highest return on investment but Division Y has

the highest residual income. Part (a) also illustrates that smaller divisions (for example,

Division Z) will look less favorable than larger divisions (Divisions X and Y) under residual

income. Note, however that Division X is the larger division in terms of investments but has

lower residual income than Division Y. The results in (b) show that, as in part (a), Division Z

has the largest return on investment, but now Division X now has the largest residual income.

Only the measurement of the value of the investment is different between parts (a) and (b),

illustrating that the measurement choice changes not only the return on investment and

residual income measures, but also potentially changes the relative rankings across divisions.

(d) Managers will only find it attractive to invest in new, more costly equipment if the

investment brings a large enough increase in income to offset the reduction in return on

investment or residual income associated with the new investment.

11-44 (a) Return on investment is division income divided by investment. Sales margin is

division income divided by sales, and turnover is sales divided by investment. Moreover,

return on investment = (sales margin) turnover.

Division Investment Division

Sales

Operating

Income

Return on

Investment

Sales

Margin

Turnover

E

$575,000

$75,000

$500,000 13.04%

15.00%

86.96%

F

700,000

91,000

542,000

13.00%

16.79%

77.43%

G

1,000,000

176,000

763,000

17.60%

23.07%

76.30%

(b) Divisions E and F have nearly identical return on investment, but E has higher turnover,

indicating that E generates more sales per dollar of investment, while F has a slightly higher

sales margin. Division G has the highest return on investment and sales margin, but the

division’s turnover is the lowest of the three divisions. Division E has the highest turnover.

(c)

Division E

Division F

Division G

Operating income

$75,000

$91,000

$176,000

Cost of capital:

46,000

56,000

80,000

$29,000

$35,000

$96,000

8% × division investment

Residual income

11-45 (a) The new return-on-sales ratio will be 0.8 × 1.2 = 0.96. The turnover will be 2.0 ×

0.8 = 1.6. Therefore, the r eturn on investment will be 0.96 1.6 = 1.536. The previous return

on investment was 0.8 × 2 = 1.6. Therefore, the percentage change is (1.536 – 1.6)/1.6 = –4%.

(b) Let x = the desired increase in the return-on sales ratio to achieve a 10% increase in

return on investment

R eturn on investment = ( return on sales )

( investment turnover).

1.1 × 1.6 = [ (1 + x ) × 0.8] × (2.0 × 0.8)

x = 0.375

Equivalently, the desired percentage increase is 37.5%.

11-46 (a) R eturn on investment = income/investment

= ($420,000/$1,400,000) = 30%

(b)

Division income

$420,000

Cost of capital:

140,000

10% × division investment

Residual income

$280,000

11-47 The response is problematic and reflects the respondent’s image of different

businesses. One industry that relies on a low ratio of profits to sales and a high ratio of sales to

assets is the grocery store business. One industry that relies on a high ratio of profits to sales

and a low ratio of sales to assets is the quality jewelry business. The business strategy in a

grocery business is to promote sales based on low costs. The business strategy in the quality

jewelry business is to promote a high price based on the nature of the merchandise.

11-48 Recall that the productivity ratio is output divided by input. Consider processing a side

of beef. The input is the weight of the side of beef. If the output measure is simply the weight of

the final products produced from the side of beef, it makes no difference how the side of beef is

processed—if it is all turned into hamburger, the productivity ratio will be the same. However,

if the output measure is the value of the products produced from the side of beef, then the

productivity ratio will assess the skill used to turn the side of beef into finished products. In

general, whenever skill is involved in turning raw materials into finished products, the

organization should consider using the value of the output in the numerator of the

productivity measure and base the evaluation of the process on the value of the output

produced relative to the potential given the quality of the inputs.

11-49 Residual income

income – required return on investment

Residual income = $1,000,000 – ($20,000,000

11-50

0.08) = –$600,000.

Golfing

Ski

Tennis

Football

Line

Line

Line

Line

Income

$3,500,000

$7,800,000

$2,600,000

$1,700,000

Investment

$35,000,000

$50,000,000

$45,000,000

$23,000,000

@ 10%

$3,500,000

$5,000,000

$4,500,000

$2,300,000

Residual income

$0

$2,800,000

($1,900,000)

($600,000)

Required return

Based on this analysis, the golfing line is marginally acceptable and the tennis lines and

football lines are unacceptable. It is only the ski line that appears to be providing a return that

would justify the investment level. These results must be interpreted with caution. The

accountant must determine whether there are revenue and cost allocation assumptions

underlying the reported income figures that could cause the reported results to be quite

different than if other assumptions were used. There should be a determination of whether

this is an unusual year or an average year. If the income numbers seem hard and the results

typical of an average year’s operations, this company must improve its performance in the

tennis and football lines substantially or think seriously of abandoning them.

PROBLEMS

11-51 One interpretation, with reasoning, is given for each of the following items. Other

interpretations are possible but should be provided with appropriate reasoning.

(a) The role is to minimize the cost of the tests while performing them properly (quality) and

when they are required (service). This is a cost center since the responsibility unit does not

affect demand.

(b) The role is to provide profits to the store by providing customers with the

services (food and how it is presented) and controlling the costs associated with

providing those services. This is a profit center since the responsibility unit can

affect sales and costs but is unlikely to affect the investment level significantly.

(c) The role is to provide a range and quality of services that meet customer requirements

while controlling costs. This is probably a cost center since the responsibility unit does not

affect revenues. However, in this setting the company might treat this group as a profit center

and allow users to buy computing services outside if they wish.

(d) The role is to minimize the cost of the maintenance services provided while performing

them properly (quality) and when they are required (service). This is a cost center since the

responsibility unit does not affect demand.

(e) The role is to minimize the cost of the customer services provided while performing them

properly (quality) and when they are required (service). This is a cost center since the

responsibility unit likely has an indeterminable effect on demand.

(f) The role is to minimize the cost of warehousing services provided while performing them

properly (quality) and when they are required (service). This is a cost center since the

responsibility unit likely has an indeterminable effect on demand.

(g) The role is to provide a reasonable return on investment to the parent by providing

customers with desired products and controlling the costs associated with providing those

goods. This is at a minimum a profit center since the responsibility unit can affect sales and

costs, and is an investment center if the publishing company can affect the investment level

significantly.

11-52 One of the first questions to ask is whether there is any purpose served by allocating

factory building depreciation space to the individual cost centers. If there is none, then there is

no point in allocating these costs—cost allocation takes time and inevitably causes

controversies. For example, some accounting systems allocate these costs in proportion to

other costs, such as labor wages. There is no point served by allocations such as these.

One purpose of allocating these costs might be to motivate the cost center managers to use

less floor space for storing work in process. (That is, to motivate them to work toward using

just-in-time manufacturing.) In this case, you might allocate the factory depreciation costs

using floor space occupied by each organization unit. In summary, the method used to allocate

these costs should serve some desired decision-making purpose or motivate some desired

behavior.

11-53 (a) This question is intended to explore the respondent’s understanding of controllable

and uncontrollable cost. The example provided should be unambiguous with an explanation of

why the item is controllable or uncontrollable. It is useful to discuss suggestions in a class

format because some costs that appear to be uncontrollable to some people may seem

controllable to other people. For example, some people will argue that absenteeism costs are

uncontrollable while others will argue that they are controllable through proper human

resource practices.

(b) The idea is that by insisting that someone be held accountable for a cost, that person will

be motivated to discover a way to control that cost. This results in making costs that were

formerly thought to be uncontrollable controllable. For example, one might try to change a

spot market transaction, where the cost is variable, into a contractual transaction where the

cost is fixed.

1154

(a)

Product

Line

1

2

3

Total

Revenue

$7,160,000

$1,900,000

$4,200,000

$13,260,000

Variable costs

4,296,000

950,000

1,680,000

6,926,000

Contribution

margin

2,864,000

950,000

2,520,000

6,334,000

Other costs

859,200

237,500

693,000

1,789,700

Segment margin

2,004,800

712,500

1,827,000

4,544,300

costs

349,000

156,000

698,000

1,203,000

Income

$1,655,800

$556,500

$1,129,000

$3,341,300

Allocated

avoidable

Unallocated costs

801,300

Company profit

$2,540,000

(b) The common interpretation is that the segment margin is the stand-alone

profit of each segment, or the financial effect on the organization if the segment

is eliminated after the fixed capacity used by the segment is either redeployed or sold off.

Beyond issues relating to the allocation of joint costs and revenues, the major

problem with this interpretation is the effects that the segments have on each

other. For example, in a financial institution, the need for checking accounts may

draw customers to the institution; if the financial institution does not offer

checking accounts, customers may take all their business elsewhere. As another

example, consider the role of a restaurant in a large hotel. On the surface,

restaurants are money losers. However, eliminating a restaurant would likely have

a negative effect on room occupancy, particularly if the hotel is a convention

hotel. This question provides an opportunity to discuss these interpretational issues

and possible interdivisional externalities in organizations.

11-55 Such a search should locate many useful illustrations. As of February 2010, a PDF file

on RadioShack® Corporation’s decision to close some underperforming stores was available

at http://media.corporateir.net/media_files/NYS/RSH/presentations/bearstearns/bear_sterns_pres.pdf . The report

discusses the corporation’s plans to take a more proactive approach to closing stores and

managing slow-moving inventory, and discusses use of gross margin per square foot of shelf

space to evaluate the performance of its inventory. The corporation also describes various

measures to control costs, including closing several distribution centers.

11-56 Transfer prices based on market prices invite, and in many cases are designed to invite,

comparisons with the costs of outside suppliers. Given cost, reliability, and quality

comparisons, many organizations are abandoning self-supply and relying on outside experts.

(This phenomenon is sometimes called hollowing-out.) Governments all over the world are

now using this tool to evaluate and improve or eliminate, internal operations. In fact, in New

Zealand , government agencies are required to sell their services to the government as if they

were independent outside suppliers.

The key is that the services must be comparable . Not only must cost comparisons be made,

but also quality and service comparisons must be made. If the outside supplier meets, or

exceeds, the potential of the insider supplier and there are no security issues (for example, the

government cannot rely on an outside printer to print classified government documents or

contract with a gang of hooligans to provide security services), then the outsider supplier

should be used.

11-57 (a) Most commentators on transfer price state flatly that, if a market price is available,

that is the price the organization should use to price internal transfers. In this case the amount

of $650 appears to be a legitimate market price since the commodity is well specified and the

purchaser is willing to sign a long-term contract. Therefore, it is inappropriate to argue in this

setting that the $650 is not a legitimate market price. If the organization wishes to maintain

the credibility, the motivational effect, and the economic insights of transfer pricing, it must

allow the selling division a price of $625 (which is the net realizable value of selling outside)

for the boards.

(b) At the moment, the value-added by the programming division, which is

apparently $75 ($700 – $625), is less than the cost of adding this value ($100).

There are only three alternatives in this situation. First, the programming division

can investigate whether the current price of $700 is too low. Second, the

programming division can try to improve its efficiency so that its programming

costs are less than $75 per unit. Third, the programming division can go out of

business.

Motivationally, it would appear most desirable to require that the programming division pay

$625 per board. The resulting losses would force the programming division to choose one, or

several, improvement alternatives. Setting a transfer price that ignores this situation and

allows the programming division to continue to show a profit would create only disincentives

for appropriate action in this setting.

11-58 (a)

(b)

(c) Because the overall ROI is higher without the new investment, Michelle’s compensation

will be much higher if she does not undertake the new investment. Therefore, the

compensation scheme does not provide incentives for a manager to undertake an investment

that would benefit the corporation.

(d) A variety of changes are possible. For example, the manager could receive a flat bonus

upon achieving a target ROI or target residual income. Another alternative is to base the

manager’s compensation on a combination of financial and nonfinancial measures. Currentperiod actions that decrease the current period’s financial performance may be creating future

value. Such actions include investments in research and development, employee training, new

distribution channels, and customer service. Conversely, companies that decrease their

investments in these activities may show good current-period financial performance but they

will have likely diminished future value. Therefore, a mixture of financial and non-financial

measures can provide information about the current period’s success in generating both

current financial performance and growth options for the future.

11-59 (a)

Net Book Value (The franchise cost is fully amortized.)

= 29,997%

Historical Cost

= 58.71%

(b) Net Book Value (The franchise cost is fully amortized.)

Economic value added = Income – Required return on investment

Economic value added = $3,000,000 – ($10,001

15%) = $2,998,499.85

Historical Cost

Economic value added = Income – Required return on investment

Economic value added = $3,000,000 – ($5,110,000

15%) = $2,233,500.

11-60 In this setting, economic value added requires that the bank can compute the revenue,

costs, assets, and asset values associated with each product line. This will require allocations

of revenues, costs and assets in a bank where many revenues are jointly earned and many

costs are jointly incurred. A remaining problem concerns the valuation of assets.

For example, consider the profitability associated with the provision of safety

deposit boxes. The bank would need to determine the revenues associated with

these boxes, which is straightforward if the boxes are billed separately but can be

complicated if the boxes are part of larger customer service packages sold to

customers. (For example, the customer might pay a monthly fee that includes a

credit card, a checking account, a safety deposit box and direct payment

privileges.) The bank would need to determine the costs associated with these

boxes.

Out-of-pocket costs such as purchasing and maintenance costs on the boxes are

straightforward. However, other costs are more problematic. Such costs include cost of space

for the boxes in the vault, which is also used to store money and records, and the time of bank

staff devoted to safety deposit box activities, when the staff are also engaged in other activities.

Finally, the cost of long-term facilities, such as the vault and bank itself, needs to be evaluated

to determine the investment base for the residual income calculation.

11-61 This is a terrible idea. Economic value added analysis is useful to identify the economic

benefits of an existing investment—it is not intended to assess a manager’s ability to manage

that investment. For example, a manager might be doing a good job managing the investment

in an asset that should be liquidated. Unless the manager controls both the investment and the

management of the investment, the two functions should be evaluated separately. The

investment should be evaluated using economic value added, and the manager should be

evaluated using budgets or benchmarking the manager’s performance to comparable

organizations.

11-62 No. The reported results might be soft numbers resting on subjective allocations.

Moreover, there may be a high degree of interaction between the manufacturing business and

installing business. If the product has an excellent reputation, installation sales might fall if

another manufacturer’s product is substituted. Finally, the current period’s results might be

unusually low. The company owner needs more investigation and data before making the

decision.

11-63 Note : The solution below draws on net present value analysis, which is covered in other

courses but not in this book.

(a)

Strathcona Paper

Year

Outflow

Savings

Depreciation

0

50,000,000

0

0

1

0

16,000,000

10,000,000

2

0

16,000,000

10,000,000

3

0

16,000,000

10,000,000

4

0

16,000,000

10,000,000

5

0

16,000,000

10,000,000

Year

Taxes

NCF

PV

0

0

(50,000,000)

(50,000,000)

1

2,100,000

13,900,000

12,410,714

2

2,100,000

13,900,000

11,080,995

3

2,100,000

13,900,000

9,893,745

4

2,100,000

13,900,000

8,833,701

5

2,100,000

13,900,000

7,887,233

Net present value

$106,388

Since the net present value of this project is positive, from the point of view of the company, it

should be accepted.

(b) The manager is evaluated based on the after-tax return on investment of assets managed.

The current investment base is $50,000,000 and the current net income after taxes is

$7,000,000, which yields a return on investment of 14% = $7,000,000 $50,000,000.

With the new investment in the first year, income after taxes will increase to $10,900,000 =

($7,000,000 + $16,000,000 – $10,000,000 – $2,100,000) and the new investment level will

increase to $90,000,000 = ($50,000,000 + $50,000,000 – $10,000,000). Therefore, the return

on investment for the first year of operations with the new trucks will be 12.1% = $10,900,000

$90,000,000.

Therefore, evaluated by the first year of operations, the manager would prefer not to make

this investment. However, the return on investment numbers for years 2 through 5 inclusive

are 13.6%, 15.6%, 18.2%, and 21.8%, respectively. Note that each year the income level will

remain the same while the investment level will be $80,000,000 in year 2, $70,000,000 in year

3, $60,000,000 in year 4, and $50,000,000 in year 5. Therefore, the manager’s attitude about

this investment will reflect how long the manager expects to remain in her current position.

(c) The after-tax residual income currently is $1,000,000 = [$7,000,000 ($50,000,000

12%)]. The after-tax residual income in the first year after the investment in the new trucks is

$100,000 = [$10,900,000 ($90,000,000 12%)]. If evaluated by the first year of operations,

the manager would not make the investment. The residual income numbers in years 2 through

5 are: $1,300,000, $2,500,000, $3,700,000, and $4,900,000. Therefore, the manager’s attitude

about this investment will reflect how long the manager expects to remain in his current

position.

11-64 The following are suggestions; individual responses may vary depending on what

performance the respondent deems critical to the organization’s success.

(a) Rate of adding or losing customers, contribution per customer, and cost of installation—an

important item not assessed by this financial control system is why customers are signing up

or leaving the company.

(b) Contribution per performance, other costs and revenues, and committed costs—an

important item not assessed by this financial control system is the type of program that

audiences find attractive.

(c) Contribution per unit, cost of developing new recipes and incorporating feedback on

existing recipes, and committed costs—an important item not assessed by this financial

control system is the rate of new product innovation.

(d) Cost per unit of work, number of clients, and services per client—an important item not

assessed by this financial control system is the degree of client satisfaction with the services

being offered by this agency.

(e) Percent available time used, profit contribution per job, and selling and administrative

support costs—an important item not assessed by this financial control system is the degree

of employee preparation for new tools and ideas that customers might demand in the future.

(f) Design cost per line, contribution per unit, and profit per line—an important item not

assessed by this financial control system is the training, future potential and public image of

the organization’s design group.

11-65 Software writers are highly skilled and creative. Many organizations believe that to

attract and keep this type of person, they have to give them freedom to exercise their skill and

creativity. However, unlimited freedom can lead to products that do not meet customers’

requirements. Moreover, in a large project the activities of independent writers must be

coordinated to achieve the project’s overall objectives. Therefore, many people believe that

the organization should control and coordinate the activities of these independent agents as

they create. The example provided for an organic organization should be clearly one where

there are relatively few rules and where decision makers are free to make decisions.

Governments are mechanistic because they believe this is how they can ensure accountability

to the legislative authority for the expenditures that they undertake and so that they will not

do anything unless it has been authorized by the legislative body. Most people believe that

governments should be less mechanistic. The legislative body should delegate the authority to

public servants to meet the spirit of the legislation without tying them down with burdensome

rules and procedures. The example provided for a mechanistic organization should be clearly

on where there are many rules and decision-making responsibilities are highly constrained.

11-66 The key in this question is to identify how many performance measures can motivate

organization units to behave in ways that are inconsistent with the good of the whole

organization. The most interesting examples are highly integrated organizations where

success depends on cooperation between the units. Examples include: A courier, any

organization using just-in-time, and an operating team in a hospital. The response should

explore why organizations tend to use measures of individual performance and the

undesirable behavior they promote.

11-67 Organizations use the functional approach to organization design to capture the

economies of scale due to specialization in task and information. The problem is coordinating

a functional organization where functional experts make decisions about their own function

without regard to the contribution by other functional areas. One approach to improving this

process is to create a team of functional experts who are focused on the product or project

rather than their function. In this context, information between functions is exchanged quickly

and the functional perspective is adapted to focus on the specific product needs. This matrix,

or team approach, to product design results in more effective and lower cost designs that are

completed in much shorter periods than the functional approach to product design. This is the

approach that Ford Motor Corporation exploited to design the Taurus automobile and is called

concurrent design.

11-68 (a) The regional offices meet all the criteria to be managed as investment centers. They

control sales, costs, and the level of investment.

(b) The corporate office performs two, virtually unrelated, functions—administration and

ordering. The ordering activity is service-oriented. The idea is to get the required product at

the lowest long-run cost. This suggests a cost center organization but how to choose a

reasonable target level of costs is a difficult issue here.

(c) While financial control systems that do mesh promote consistency of purpose and view,

the financial control systems do not have to mesh. The key is whether the operational

activities related to ordering at the corporate office mesh with the regional requirements. This

cannot be promoted or controlled using a financial tool. Performance measures will have to be

established that assess the center’s ability to find the products required by the regions and

supply them when the regions require them and at attractive prices.

11-69 (a) The issue turns on the respondent’s view of the role of accountability in

organizations. If the respondent believes that individuals can be motivated to improve the

organization’s performance without holding them specifically accountable for certain facets of

performance, then the issue of controllable and uncontrollable can be avoided. However, if the

respondent believes that people must be held accountable for something to make them

interested in improving performance, then the issue of controllable versus uncontrollable

must be addressed.

(b) The organization would likely move to team rather than individual measures of

performance. All members of the team would be expected to deal with opportunities to

improve performance. Therefore the question of whether any one item is controllable or not

by an individual would disappear and be replaced by questions about group performance.

11-70 The major issue in choosing a transfer price is motivating the managers of the two

divisions to behave in a way that makes the organization’s profits as large as possible.

For existing home kits, the manager of the sales division will want to buy home kits as long as

the sales division can realize a profit on selling the home kits to the final customers. Therefore,

the transfer price must not exceed $35,000, which is the selling price of $40,000 less the

selling division’s cost of $5,000 per home.

The manager of the manufacturing division will want to sell existing home kits as long as the

manufacturing division can realize a profit on selling the homes to the selling division.

Therefore, the transfer price must exceed $30,000 ($33,000 1.1) , which is the variable cost

of making the home kits.

Therefore, any transfer price between $30,000 and $35,000 for the existing homes will cause

the manufacturing division to make, and the selling division to buy and sell, all the home kits

that the manufacturing division is capable of making.

Turning to the proposal to make cottage kits, recall that the manufacturing division is

currently operating at capacity and will therefore have to give up production of home kits in

order to manufacture cottage kits. From the company’s perspective, t he company’s

contribution margin per home kit is $5,000 = ($40,000 – $30,000 $5,000). Let P = the price

at which the company is indifferent (with respect to profit) between selling all home kits or all

cottage kits. Home kits require 10 machine hours (mh) per unit and cottage kits require 13 mh

per unit, and 5,000 mh are available per year. Assuming that the selling cost of the cottage kit

is the same as the selling cost of the home kit ($5,000 per unit), equating the total contribution

margins for the two options requires the following:

(5,000 mh

13 mh per cottage) × (P – $30,000 – $3,000 – $5,000) =

(5,000 mh

10 mh per home) × ( $40,000 – $30,000

$5,000)

Thus, P – $38,000 = ( $5,000

10 mh per home) × (13 mh per cottage), so

P = $38,000 + $6,500 = $44,500.

Note that $6,500 is the opportunity cost of producing and selling a cottage kit instead of a

home kit. This opportunity cost is the $500 of contribution margin per mh for home kits,

multiplied by the 13 mh required per cottage kit. (If one wishes to take into account only

production in whole numbers, then 5,000 13 = 384.62 will have to rounded down to 384,

and the necessary price will be approximately $44,511.)

The analysis from the manufacturing division’s point of view is similar.

Let TP = the transfer price for cottage kits at which the division is indifferent between

transferring home kits at variable cost plus 10% ($30,000 + $3,000) or cottage kits at TP per

unit. Assuming production of either all home kits or all cottage kits and equating the total

contribution margins for the two options requires the following:

(5,000 mh 13 mh per cottage) × (TP – $30,000 – $3,000) =

(5,000 mh

10 mh per home) × ($33,000

$30,000)

TP – $33,000 = ( $3,000/10 mh per home) × (13 mh per cottage), so

TP = $33,000 + $3,900 = $36,900.

This transfer price incorporates the original variable cost of $30,000, the incremental

manufacturing cost of $3,000, and the $3,900 opportunity cost to the manufacturing division

for making a cottage kit instead of a home kit, given the existing transfer price for home kits.

Thus, the manufacturing division will not be willing to accept a transfer price less than

$36,900 per cottage kit. Assuming a selling price per cottage kit of $44,500, the selling division

will not be willing to pay more than $39,500 ($44,500 – $5000). Therefore, a transfer price

between $36,900 and $39,500 should induce both managers to be willing to engage in the

transfer.

11-71 This question explores some of the practical problems of using the return on

investment criterion to evaluate on-going investments in fixed assets. The return on

investment tool was originally designed to evaluate new investments rather than on-going

investments. In the case of new investments, there is no confusion about the investment

amount. When this tool is used to evaluate on-going investments important valuation

problems have to be resolved.

If the original notion of return on investment is applied to evaluate on-going investments, the

philosophy would be to assume that in each period the organization makes a reinvestment

decision. Therefore, the amount implicitly reinvested is the net realizable value (disposable

value) of the investment. In a situation where there are multiple uses of the resource, the

relevant net realizable value is the highest value. Therefore the return would be the income,

plus the change in the net realizable value of the asset during the year, divided by the net

realizable value of the asset at the end of the year.

(a) In this case we do not know the change in the net realizable value of the property during

the year. Therefore we could compute the return on investment as 7.43% = [$130,000

($2,000,000 – $250,000)], which is net profit divided by selling price less disposal costs (the

highest realizable value for the land).

(b) The first question to resolve is whether the current results are typical. The second

question to resolve is the basis that will be used to make this decision. If the basis is purely

financial and if the company requires a return on investment greater than 7.43%, the asset

should be put to its most profitable use, which would be to demolish the building and sell the

land, netting $1,750,000.

CASES

11-72 (a) Shellie is likely to focus her efforts on layout design, the product line that shows

the highest reported profit. With the information provided up to this point, one can conjecture

that Shellie may be undercharging for layout design because there is great demand for

Shellie’s layout design services, but no other lawn and garden businesses in the city are

attempting to compete for the layout design business. If Shellie is undercharging for layout

design and thereby not adequately covering associated costs, profits will continue to

deteriorate.

(b)

Shellie’s Lawn and Garden

Resource Use Information

Trucks and

Cost

Capacity

Rate

Used

Allocation

Unused

$50,000

800

$62.50

600

$37,500

$12,500

37,500

1,500

25.00

1,200

30,000

7,500

150,000

400

375.00

400

150,000

0

87,500

700

125.00

500

62,500

25,000

related costs

Lawn mowing

equipment

Layout design

equipment

Other

maintenance

equipment

$325,000

$280,000

$45,000

(c)

Shellie’s Lawn and Garden

Product Line Income

Statements

Lawn

Mowing

Layout

Design

Other

Maintenance

Total

Revenues

$287,500

$218,750

$312,500

$818,750

Direct costs

156,250

70,000

181,250

407,500

Margin

131,250

148,750

131,250

411,250

Own

30,000

150,000

62,500

242,500

Trucks

12,500

12,500

12,500

37,500

Cost of unused own

7,500

0

25,000

32,500

$81,250

–$13,750

$31,250

$98,750

Cost of used capacity

capacity

Product line profit

Cost of unused shared

12,500

capacity (trucks)

General business

50,000

costs

Organization profit

$36,250

Note that the product line profit numbers do not include the $50,000 of general business

costs and the $12,500 of costs of unused truck capacity, since there is no practical way of

allocating these costs to any one of the three lines of business. They must be covered by the

margins created by each of the three business lines.

(d) Based on the exhibits in part s (b) and (c) , cutting back on lawn mowing and other

maintenance is undesirable if capacity stays the same. Both these product lines have unused

capacity. The layout design business is draining profits. The prices charged for layout do not

reflect the costs of the associated specialized equipment, confirming the conjecture in part (a)

that Shellie’s low prices are generating demand and discouraging competition. Shellie can

raise prices on the layout design business and try to increase volume in the lawn mowing and

other maintenance business, to use available capacity.

11-73 (a) This is an organization where the activities of all the elements of the system must

work together and be very highly integrated. This is a setting where basing rewards on

individual measures of performance can be very dysfunctional. Since the investment center

approach requires that the costs, profit, and investment levels of each responsibility center be

computed, it would seem, on the surface at least, that this is not the type of organization where

an investment center approach can be properly used.

(b) The existing performance measurement system should be expanded beyond financial

control to include measures of performance that reflect what customers require. Performance

measures relating to on-time performance, sorting error rates, and customer complaints

should be developed. These measures could be used not only as bases for rewards, but also to

focus attention on problems relating to customer service, service failures, and cost control.

Similarly, issues important to other stakeholders, such as employee training, relations with

suppliers, and community relations are important performance measures to assess.

(c) The organization should consider eliminating the investment center approach.

The existing responsibility centers could be organized as cost centers and the

performance measurement system expanded along the lines suggested in part (b).

Each responsibility unit manager could contract with the other managers and the

process controller to deliver cost, quality, and customer service results. Unit

members could be rewarded based on their ability to meet cost, customer service,

and quality targets of their unit and the profit of the overall operation. The

performance measurement system could also reflect the requirements of the

organization by other stakeholders (such as public safety considerations in the

operation of the courier trucks) if they are deemed controllable by the

responsibility center managers. The current financial system is distracting the

organization’s attention by focusing on allocation issues rather than customer

service issues.

11-74 (a) This is a situation where historical and political issues, combined with

an inappropriate delegation of organization responsibilities to organization units,

created a problem that caused customer and safety concerns and organization

frictions. Given the structure and the division of responsibilities, the event

described in the case was virtually certain to occur at some point in time.

Moreover, the bureaucracy and inability to handle priority calls relating to citizen

safety issues exacerbated the underlying organization problem. There are at least

five problems here: A poor organization design, a poor division of responsibilities

among the organization units, a bureaucratic structure within each department that

requires approval by specific individuals and makes no provision for replacements

when individuals are unavailable, a lack of initiative that is widespread, and no

provision to provide an emergency response group that cuts across departmental lines.

(b) Within the existing structure this incident could have been avoided by creating a multidepartment team to handle emergency and safety prob lems that cut across departmental

lines.

(c) The city manager should accept the blame for what happened and ensure the public that:

Steps will be taken to ensure that this event will not happen again, that these steps will be

taken promptly, and that the manager will report back to the public within 2 weeks with the

change proposal.

(d) The city must be reorganized so that related activities fall under the same department.

The cost focus of each department might be replaced by a focus on accomplishing service

objectives, within the constraint of not overspending. Response teams, consisting of members

from appropriate departments should be organized to deal with predictable emergency and

safety incidents. These teams should be ready to respond to situations without requiring time

for approval and scheduling.

金榜VIP已享免费阅读及下载

打开百度APP阅读全文

VIP全新升级 买1得3

本文立即免费保存

赠百度阅读VIP精品版

100W文档免费下载

5100W文档VIP专享

立即升级

开通VIP,免费获得本文 新客立减2元

试读结束

文章已购买,您可以发送到邮箱查看剩余内容

发送到邮箱

试读结束,剩余内容购买后可下载查看 本文仅一页,购买后可获取全文

试读结束,购买后可阅读全文或下载 试读结束,购买后可阅读全文

券后价¥${shopVoucherInfo.shopConfirmPrice/100}${payPrice/100}

${voucherDetailTagText} ${getVoucherTagText}

${voucherByeBtnText}

试读结束,剩余内容购买后可下载查看

本文仅一页,购买后可获取全文

试读结束,购买后可阅读全文或下载

试读结束,购买后可阅读全文

下载文库客户端,离线文档随时查看

超出复制上限

现在开通VIP,还可获得

免费下载文档

付费文档8折

点亮专属身份

开通VIP,享无限制复制特权

本文配套内容

含${item.docNum}篇文档

${item.title}

¥${item.price}

立即购买

查看文集

相关推荐文档

•

${searchSpecial.title}

•

${v.docTitle}

推荐 热门 好评

${btnText}

打开百度APP

精品课程

•

•

${item.title}

免费 ¥${item.price}¥${item.oriPrice} ¥${item.oriPrice} ${item.orgName}

•

${item.videoCount}课节

返回百度搜索

下载原文档,方便随时阅读

下载文档

2亿文档资料库

涵盖各行课件、资料、模板、题库、报告等

多种记录存储好工具

提供图转文字、拍照翻译、语音速记等

APP端内容永久保存

随时阅读,多端同步

立即下载

文档售卖收入归内容提供方所有,文库提供技术服务

看视频广告,获取20元代金券礼包

看视频,立领券 视频大小约3.7M

恭喜!您收到一张

文档优惠券

有效期:24小时

${layerInfo.voucher_price / 100}元 优惠券

满${layerInfo.min_pay_amonut / 100}可用

立即领取

您是老用户,送您2张代金券

•

5元

•

•

适用除连续包月外的其他VIP

•

•

24小时内有效

•

10元

•

•

限百度文库VIP-12个月适用

•

•

24小时内有效

领取优惠券

您已成功领取老用户福利

已转存到百度网盘

存储在文件夹【来自:百度文库】

去看看

文库新人专享礼包

限时免费

价值¥500+

去文库APP免费领