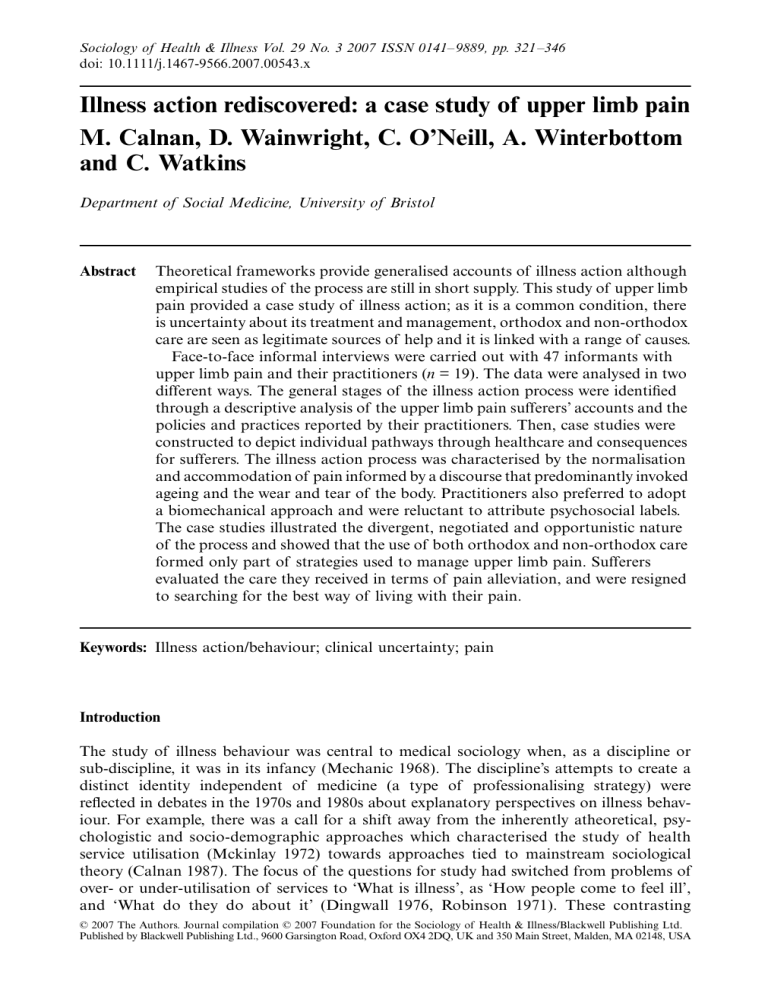

Sociology of Health & Illness Vol. 29 No. 3 2007 ISSN 0141–9889, pp. 321–346 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00543.x M. Sociology SHIL © 0141-9889 O 3 29 Illness riginal Blackwell Calnan, action Article ofD. Publishing Health and Wainwright, upper &Ltd Illness Ltd/Editorial limb C. O’Neill pain Board et al. 2007 Blackwell Oxford, UK Publishing Illness action rediscovered: a case study of upper limb pain M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill, A. Winterbottom and C. Watkins Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol Abstract Theoretical frameworks provide generalised accounts of illness action although empirical studies of the process are still in short supply. This study of upper limb pain provided a case study of illness action; as it is a common condition, there is uncertainty about its treatment and management, orthodox and non-orthodox care are seen as legitimate sources of help and it is linked with a range of causes. Face-to-face informal interviews were carried out with 47 informants with upper limb pain and their practitioners (n = 19). The data were analysed in two different ways. The general stages of the illness action process were identified through a descriptive analysis of the upper limb pain sufferers’ accounts and the policies and practices reported by their practitioners. Then, case studies were constructed to depict individual pathways through healthcare and consequences for sufferers. The illness action process was characterised by the normalisation and accommodation of pain informed by a discourse that predominantly invoked ageing and the wear and tear of the body. Practitioners also preferred to adopt a biomechanical approach and were reluctant to attribute psychosocial labels. The case studies illustrated the divergent, negotiated and opportunistic nature of the process and showed that the use of both orthodox and non-orthodox care formed only part of strategies used to manage upper limb pain. Sufferers evaluated the care they received in terms of pain alleviation, and were resigned to searching for the best way of living with their pain. Keywords: Illness action/behaviour; clinical uncertainty; pain Introduction The study of illness behaviour was central to medical sociology when, as a discipline or sub-discipline, it was in its infancy (Mechanic 1968). The discipline’s attempts to create a distinct identity independent of medicine (a type of professionalising strategy) were reflected in debates in the 1970s and 1980s about explanatory perspectives on illness behaviour. For example, there was a call for a shift away from the inherently atheoretical, psychologistic and socio-demographic approaches which characterised the study of health service utilisation (Mckinlay 1972) towards approaches tied to mainstream sociological theory (Calnan 1987). The focus of the questions for study had switched from problems of over- or under-utilisation of services to ‘What is illness’, as ‘How people come to feel ill’, and ‘What do they do about it’ (Dingwall 1976, Robinson 1971). These contrasting © 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA 322 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. perspectives appear to have persisted in the study of illness behaviour (Young 2004) although new theoretical frameworks have been developed (Pescosolido and Boyer 1996). As Blaxter (2004) points out, however, there are a lack of studies on how people act on their illness to match the wealth of evidence about how they perceive it, experience it and narrate it (Lawton 2003). The aim of this paper is to attempt to fill this gap by presenting evidence from a study of upper limb pain which provides a case study of illness action. The reasons for focusing on upper limb pain will be discussed later but before, there is a need to consider recent theoretical developments in illness behaviour. Theoretical background In the 1950s and 1960s various frameworks were proposed for charting the pathways and explaining the stages involved in the response to problematic signs and symptoms and the experience of illness (Mechanic 1968, Rogers and Elliott 1997, Zola 1973). These approaches to illness behaviour were organised (Dingwall 1976) into what have been termed the individualistic and collective approaches. The former approach attempted to account for observed behaviour by reference to the personal characteristics of individuals whereas the latter placed individuals at the nexus of a balance of social forces, and accounts for their behaviour in terms of the forces that impinge on them. These approaches were the focus of a number of criticisms (Dingwall 1976) not least from sociologists who argued that through their reliance on natural scientific methods they have failed to develop a sociological theory of illness. More coherent sociological approaches were proposed (Dingwall 1976, Fabrega 1974, Robinson 1971) emphasising the need to take a pluralistic perspective on knowledge and an interpretive approach emphasing social meaning and action. These (Dingwall 1976 and Fabrega 1974) frameworks did suggest a form in which decision-making may occur although Dingwall, unlike Fabrega, did not make the a priori assumption that decisions about how to respond to signs and symptoms were based on a cost-benefit model. Dingwall suggests that when a disturbance affects the body, depending on the priorities accorded to the disturbance, the automatic expectation of a stable and predictable relationship between a person and their body may not be sustained. If he or she was to continue to sustain a presentation of themselves to others as essentially a normal person, then remedial action is needed. The process of interpretation of problematic signs and symptoms was, according to Dingwall carried out within a framework of lay health knowledge as opposed to official, health knowledge generated by scientific medicine. The framework included options for action which were to ignore the disturbance, wait and see what happens or decide to seek help. The decision-making process could be interpersonal, involving informal and formal contacts. This theoretically informed, illness action framework (Dingwall 1976) has not spawned a plethora of ‘ethnographic’ or other empirical research even though it raised a number of fundamental research questions. It has, however, come in for some criticism (Calnan 1987) not least because it neglected to place ‘lay’ interpretative work within a wider structural and cultural context and played down the interplay between structure and human agency. For example, lay and official knowledge may not be as distinct as proposed because of the power of scientific, medical discourse and the influences of medicalisation, at least in western society (Cornwell 1984). More recent theoretical approaches (Pescosolido 1991, 1992, Pescosolido and Boyer 1996) have addressed this question of structure and agency through © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 323 the concepts of social networks and social support. These are portrayed as acting as a mediator between the micro- and macro-levels and combines the career and social network approaches (Young 2004). Thus, decision making about illness and help seeking were recognised to be the result of negotiation among actors embedded in social networks, and help-seeking interaction was seen to be shaped by the involvement of actors in structured relations (social networks). The influence of social structure came to be viewed as emerging mainly from regularities in the pattern of relations among actors (network structure) rather than from the social and demographic characteristics of individuals (Uehara 2001). Empirical research informed by Pescosolido’s framework is emerging (Carpenter and Ducharme 2005), particularly focusing on mental health. This latter work (Pescosolido 1996, Pescosolido et al. 1998, Pescosolido and Wright 2004) has shown that client pathways to mental health services are divergent and can be a product of choice, coercion or simply ‘muddling through’. This research, however, with its emphasis on the structural influences of social networks, has tended to negate the interpretative work involved in decision-making. The limited empirical evidence, which sheds light on the nature of these decision-making processes involved in illness actions, can be found mainly in response to acute physical illness and injury (Calnan 1983, Mechanic and Angel 1987) and particularly the life threatening conditions such as the use of emergency care for cardiac events (Alonzo 1984, Cowie 1976, Ruston, Clayton and Calnan 1998). This is surprising, given the sizeable theoretical and empirical literature on the illness experience of those with chronic illness (Charmaz 2000). This work into acute illness and injury identifies in particular how the timing of the decision to seek formal help is influenced by how people make sense of signs and symptoms, drawing on common sense knowledge and the strategy of normalisation. This research has also shed light on the structure of decision making showing that in some contexts it can be routinised, and patients have clear ideas about what is wrong and have recipes for action (Calnan 1983). These studies have also illustrated the influence of organisational factors associated with the structure and values of healthcare systems (Calnan 1987) on how patients negotiate access to healthcare. Finally, there is evidence about the way social circumstances and context-related factors (Alonzo 1984) influence patterns of illness action. This is illustrated, as Rogers and Elliott (1997) suggest, in the paradoxical relationship between work and illness action where some work settings restrain and others encourage seeking formal help. In summary, various theoretical frameworks have been proposed to explain the illness action process and pathways into and out of care, yet empirical research, which provides insights into and can elaborate on the substance of these processes and pathways, is still in short supply. Upper limb pain: a case study Upper limb pain has the potential for being a prime example for a case study of illness action, as it brings together a number of characteristics. First, it is common and disruptive in that it might lead to time off work although the majority are not seriously disabling (Bongers 2001, Coggon, Palmer and Walker-Bone 2000), with only a minority consulting a general practitioner. There is evidence that non-orthodox care is a popular source of help for sufferers with ULDs (Paterson and Britten 1999, Thomas et al. 1991), although whether the use of complementary therapy (CAM) acts as a complement to or substitute for orthodox care still remains unclear. © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 324 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. Secondly, upper limb disorders (ULDs) fall into two broad clinical categories (Palmer and Cooper 2000): specific disorders (such as carpel tunnel syndrome) and non-specific (often chronic and troublesome) pain with the highest proportion falling into the latter category. However, these conditions are heterogeneous by nature which has sown the seeds of confusion and controversy. A variety of labels such as ‘repetitive strain injury’ (RSI), ‘cumulative trauma disorder’ (CTD) and ‘work related upper limb disorder’ (WRULD) have been employed, in particular, when a relationship between symptoms and work activities has been suspected. These labels are seen to be unsatisfactory in several respects (Canaan 1999, Coggon, Palmer and Walker-Bone 2000), not least because clinically indistinguishable disorders may arise for other (non-occupational) reasons. This uncertainty about the status of ULDs, most notably the non-specific conditions, where there is no evidence of a clear pathology, has consequences for practitioners in terms of management, treatment and understanding, and also for causation (Adamson 1997, Rhodes et al. 1999). They may present a challenge to the patient and their sense of identity (May, Doyle and ChewGraham 1999, Nettleton et al. 2004). For example, if they are believed to be fabricating an illness for gain, their integrity is undermined, and if they continue to suffer unexplained pain the associated worry (Aldrich, Eccleston and Crombie 2000) can lead to a sense of a frozen future (Heilstrom 2001) which can prove mutually debilitating. Thus, sufferers with upper limb pain can experience either a temporary or long-term disorder. Thirdly, the ‘scientific’ discourse on ULDs has identified a range of possible causes of ULDs. One of the most common has been the working environment either directly causing or aggravating the problem. High levels of exposure to physical factors (e.g. repetitive lifting of heavy objects, in extreme or awkward postures) are the most common explanation for work-related ULDs (NIOSH 1997, Panel on Musculoskeletal Disorders 2001). More recent research argues against over-reliance on physical or biomechanical explanations and for the need to take into account the psychosocial make-up of the individual, their ability to cope with their working environment and the importance of the role of job stress and psychosocial demands (Macfarlane, Hunt and Silman 2000, Palmer and Cooper 2000). Some researchers have argued that the effects of these conditions are exacerbated or even caused by job dissatisfaction and anxiety, or that workers with boring, repetitive and low paid jobs convert psychosocial dissatisfaction into physical experiences of pain (Canaan 1999). One further explanation suggests that these work-related problems may have been taken on by workers to link normal aches and pains caused by work with previous injury, either unintentionally or by being encouraged by a compensation system which provides financial incentives to articulate grievances in medicalised terms (Canaan 1999, Summerfield 2001). Upper limb pain is common but there is uncertainty over its treatment and management, with both orthodox and non-orthodox care seen as legitimate sources of help. The cause of upper limb pain is linked with both physical and psychosocial factors, particularly in relation to work-related episodes where it has also been linked with ‘claims-making’. Thus, with this combination of characteristics it appears to be a prime case for studying neglected questions in illness action. The study presented here examines illness action across the broad spectrum of upper limb disorders, including those with specific and non-specific pain. The little research that has been carried out into sufferers’ experiences of upper limb pain has involved those at the end of the continuum with non-specific labels such as RSI (Arskey 1998, Reid, Ewan and Lowy 1991) involved with self-help groups. It explores the pathways through healthcare followed by ULD sufferers, and attempts to account for variations in patterns of illness action. More specifically, it explores how sufferers make sense of their problem, how they manage it, © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 325 when and where they seek formal help and why, and how they evaluate the care they receive. It examines how their practitioners manage and treat the conditions they present and what the consequences are for the patient. Methods Design strategy As it was proposed to obtain information from a broad range of informants and to compare the experiences of sufferers at different points in the course of management, diagnosis and treatment, the design consisted of a community-screening survey followed by face-to-face, informal interviews with a purposive maximum variation sample of ULD sufferers. The community-based screening survey was carried out on a random sample from the working population of patients registered with a sample of five general practices in a local area in south west England. Practices were purposively selected according to practice characteristics including partnership size and the socio-demographic characteristics of the practice catchment area, i.e. whether they served an affluent or deprived population. A random sample of 4,998, aged 25–64, was selected and the probability of selection was constant across the practices. Of the original five thousand, 73 were excluded because of death, moved away etc. The final response rate after four mailings (the initial mailing plus three reminders) was 56 per cent (n = 2,781) with four per cent refusing and 40 per cent not replying. The survey was carried out in the winter of 2002/3. A comparison of the agegender characteristics of the survey respondents with the combined practice population from which they were randomly selected showed, for both men and women, that older people were more likely to respond than younger people (chi2 = 196.1, d.f-9, pl.001). The aim was to select informants at different points in the pathway from initial awareness of problems, through consultation, diagnosis and treatment. Thus, informants were identified for follow-up according to strict criteria, using data from the screening questionnaire: ‘experienced arm pain during previous 12 months’ (50% of postal sample); ‘duration of arm pain’ (a month or less or more than a month); ‘disabled or not’; ‘consulted a health care professional or not’; ‘employed or not’. ‘Disabled or not’ was scored on the basis of responses to questions about level of difficulty in carrying out five activities of daily living, i.e. sleeping, getting dressed, carrying bags, opening doors and routine jobs around the house. Informants were randomly selected from each category (see Figure 1). In all, 50 informants were contacted according to these criteria and who had previously reported that follow-up was acceptable. However, it was only possible to interview 47 of these of whom 32 were women and 15 were men, and the age range was from 27 to 64 with the majority (31) being aged between 40 and 59. Thirty-four reported long-term pain and 13 short-term pain. Each informant was asked to nominate healthcare workers they had seen in connection with their ULD for possible follow-up interviews. Fourteen out of 19 possible GPs were interviewed along with two physiotherapists (one private and one NHS), one osteopath, one chiropractor and one hospital specialist. If the healthcare practitioners had dealt with more than one patient in the follow-up sample, then the interview focused on only one of the cases. The data were complemented by information from medical records which was mainly used to provide background information for the healthcare practitioner interviews. Data from a nurse examination (Palmer et al. 2000), carried out on the informant after the interviews took place, were used to provide baseline diagnostic evidence. Forty-six of the 47 informants agreed to a nurse examination. The distribution of diagnostic categories identified © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 326 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. Figure 1 Informant selection criteria from this examination for individual cases showed 20 had specific diagnoses, in 12 cases pain was reported at the time of the examination but this was non-specific, and no diagnostic category could be allocated; in 14 cases there was no pain reported at the time of the examination. Shoulder pain was the most common site of pain but many individuals had multiple problems with both specific and non-specific diagnoses. A statistical analysis of the survey data also showed that upper limb pain was rarely reported in isolation, and those with upper limb pain were also highly likely to report lower back pain and/or knee pain. Interviews were carried out by the researchers in the patients’ homes and those with healthcare workers in their surgeries. All interviews were audio taped and transcribed. The interviews with patients were guided by a list of topics and questions which were derived from different cognitive stages in the illness action process (Dingwall 1976) and pathways through healthcare (Calnan 1987), e.g. initial recognition and interpretation of the problem, decisions about what to do about the problematic experience, self management and when, where and why help was sought, experience of the consultation with a healthcare practitioner, management and treatment and their consequences. The interview was however flexible and informal in order to reveal essential themes of the individual’s experience (Britten 1995). The interviews with the practitioners focused initially on the case of the patient in question, and then broadened out to a discussion about general policies and practices. Analysis strategy The first analysis was derived solely from the themes which emerged from the interviews with the ULD sufferers and the practitioners. This analysis describes the general strategies adopted by informants for managing their pain and related disorders, and by their practitioners for treating their disorders. This is complemented by analysis of specific case studies (n = 9). The strength of the case study is that it provides an overall picture of pathways © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 327 Figure 2 Common themes and sub-themes from the analysis of the interview data through healthcare and the outcomes and consequences for sufferers. The three case studies presented specifically illustrate points of agreement and divergence between the healthcare practitioners and the patients, as well as the negotiation process that is engaged in the attempt to resolve these differences. The case studies were constructed with data from the interviews with patients, their practitioners, medical records and nurse examinations. The interviews were independently analysed by two of the authors and initially involved the examination of a sample of transcripts to identify the principal themes. Coding schemes were then compared and a common category and theme definition agreed. The transcripts were coded using the Atlas.ti software, and codes in each interview were compared with those in other interviews to take account of emergent themes and to create broader categories linking codes across interviews, i.e. using the technique of constant comparison (Strauss 1998). Exceptions to the thematic framework (see Figure 2) were sought and the framework was modified, if appropriate, to take account of the deviant cases. Stages of illness action: the sufferer’s perspective (see Figure 2) Interpreting symptoms and making sense of what is wrong Informants who reported arm pain tended to recall that something was wrong in terms of the sudden onset of physical pain. This recognition of the problem usually occurred once the pain had actually prevented them doing something routine at work or around the house. The informant’s theory of onset was frequently that it was sudden and unexpected: No, I don’t remember doing anything, I just got this very severe pain and I couldn’t lift my arm. It lasted for two or three days and then I went to see the doctor (B2052). The onset of symptoms was often linked to a very specific activity, for example: © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 328 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. Well it was at work actually, we were moving a patient, and I felt and I thought, oh gosh that hurt a bit, the hoist wasn’t working at the time and I just thought, oh I’ve done something with my shoulder and it just got worse and went on really. I guess cos I didn’t rest it, it just aggravated it really (A1018). But the informants themselves also kept in reserve a number of other possible explanations and, if the sudden over-exertion theory no longer made sense as the symptoms persisted, they resorted to recalling the condition, gradually building it up over time: My aches and pains started after it . . . I was very ill with a high fever and shortly afterwards I started experiencing these aches and pains. But then the symptoms went away and the pain started. Interviewer: Do you think they are related? Yes, well the doctor did say that sometimes that’s how these things start. That’s why I think it. He said did you have any thing severe and sort of happening, a traumatic happening in the last six months, and I said the only thing I could think of that was unusual was the symptoms of the virus (N2119). Wait and see: ‘it’s natural wear and tear’ Deciding to ignore the early stages of the pain experience on the assumption that it would pass was the most common response, unless the informant had some reason to suspect a definite pathology. Informants who associated their pain symptoms with a family history of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) like arthritis, or with a heart condition like angina wanted to rule that out quickly: The reason I was concerned about angina, was because my father, when he was in his fifties, started to suffer from angina, and my mother had a heart condition, and my father died when he was 64, and my mother died when she was 77, and I thought ‘oh dear is this something that I have got to look forward to as I get older’ (G2248). The decision to adopt a ‘wait and see’ approach was most commonly used by informants who would not consult their GP at least until they had allowed for what they saw as a normal amount of time for natural healing to occur, i.e. they believed that the symptoms were temporary and would pass, and also that the symptoms were a natural part of the ageing process: I try to only go when I am bad. I usually wait a while and see if it wears off but you get aches and pains at my age. Basically I work with the rule that what can clear up by itself isn’t serious so I wait but if it is something specific I don’t go until I have tried simply waiting it out and treating myself (A2954). Work characteristics and activities were rarely invoked but when they were the assumptions of causality were often tentative and uncertain: this from a nurse with shoulder pain: I just think that when I’m not at work I can tell the difference but I don’t make too much of it because we all go home with aches and pains. Informants also invoked a ‘moral’ dimension to the decision in that informants who wait and see presented themselves as stoical and strong and regarded persistent help-seeking as a weakness: © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 329 I would rather not make a meal of it . . . I think that if I stick my head in the sand, then perhaps I can manage . . . I am pretty bloody-minded and I am not going to let it beat me . . . Yes I could indulge and feel sorry for myself and sit around all day and do nothing and probably create a lot more health problems for myself (A4324). Wait and see: reluctance to seek orthodox care Most instances of reluctance to consult were based on the assumption that the GP was a very busy person and arm pain was something that, at least until it became persistent and disabling, was not a priority. Informants attempted to work out when something was a legitimate complaint worth bothering the doctor with. In addition, they were more likely to be able to access other sources of information and saw self-treatment as a more legitimate approach: I mean generally being a sort of proactive person, if there is something I want to find out about I will go and look myself, knowing how busy doctors are, I would rather go and look on the internet; that’s probably the primary source as far as I am concerned rather than go and bother them (A3033). Informants were also concerned about wasting the doctor’s time: Yes because as I said it is an ache more than a pain. Like most men I don’t have a low pain threshold. I try and keep away from the doctor because I know they have got enough to do. I try and work on the principle that if I go to the doctor there is something wrong (I3994). There were, of course, informants who did not want to consult because of previous experiences with the medical profession and who were unwilling to expose themselves to what they expected would be poor treatment: I suppose it’s personal reasons really, it’s a lot to do with the fact that I lost both my parents quite close together and I became sceptical about going to the doctor’s. That’s why (I3127). But other informants preferred not to consult about their arm pain on the assumption that nothing could be done about it: I can’t remember discussing it with Dr X because I may have mentioned it at sometime but it’s just something that seems to go on and, em, I just work with it I suppose. I don’t really expect anything to be done about it to be honest. I expect he’d give me some more pills or something but its not as if, its not like you need to take painkillers its just annoying . . . (N935). Managing pain: the preferred strategy of self-management Most informants tended to have at least tried some self-treatment before approaching healthcare practitioners for help and this tended to involve the use of creams and pills as well as making lifestyle changes. The common explanations for the pain that were considered by most of the informants, before visiting the healthcare provider, were associated with © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 330 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. their posture and ergonomic factors at work. Thus, they would try out new grips on sporting equipment, lightweight kitchen utensils, or wrist supports for typing: Yes. I bought a specially designed mouse mat, which is quite good. See that supports the wrist. If I had more room on my desk I would get one of those things that would support your wrists as well when you are typing (I3127). For the most part though the pain was not perceived to be bad enough to warrant a major change in lifestyle, and none of the informants recalled giving up anything completely because of pain in the upper limb. Many had designed their own system of exercises to get the blood circulating again since the pain was often seen to act like cramp: Nothing to moan about. Each time it has been after I’ve been lifting and working like this [raise arms above head] doing fitting and things in someone’s house and then I might get a twinge. But I have learned by now just to swing my arm around. Sit down have a cup of coffee and I’m all right (M980). Most were just resigned to getting on with it and rather than paying too much attention to it they preferred to self-treat with painkillers: Only when it gets bad, because I know how to deal with it, I take the tablets and I take the Ibuprofen if things are a bit sore, I put Ibuleve on the left elbow, so I haven’t bothered to see the doctor, because I know there is not really a lot they will do, except perhaps give me another injection (A3033). Reluctance to draw attention to the problem was often motivated by fear of being seen as a problem employee, particularly among the older women in the sample. For example, this woman had resisted her doctor’s advice to take time off work because of the pain, and in fact admitted that her initial reluctance to consult was partly due to her expectation that that was exactly what he would advise: No, just in the end I knew I had to do something. I know it sounds daft but I don’t want to have time off work, and I was frightened he was going to say I’d have to have time off, and because of my age I don’t want that label of oh she’s getting old. Seeking help from orthodox care: pain management rather than diagnosis The most common reason for consultation was the exhaustion of self-treatment options; with the pain getting worse and the perception that this pain was different from more familiar ailments, like a pulled muscle, it needed to be treated in a different way. The first port of call for these informants tended to be the GP’s surgery. It was common for informants to report that they had not received a diagnostic label for their upper limb problems. However, failure to get a diagnosis did not usually cause too many problems for informants because it did not preclude the possibility of treatment. There was an awareness that pain conditions could be difficult to diagnose, and in fact this was often what discouraged them from seeking medical advice in the first place. A diagnosis, where one was given, was often perceived to be based on cursory examinations and discussions with medical practitioners: © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 331 I said I had dreadful pains in both my shoulders. I said it was hard to move my head and my hands and he just said: ‘Can you fasten your bra?’ I said no. He said: ‘Can you put your hands above your head?’ I said no. He said ‘I think you’ve got this myalgia,’ and that was it. It was as simple as that (N2119). Different types of problems arose when the informant adopted the ‘shopping around’ approach, visiting a number of different practitioners who offered different diagnoses or different treatments. Sometimes this arose where the informant was referred to another specialist by their GP: So I go there and they X-rayed it and they came up with osteo-spondilytis. That’s when they put me in the collar and in about a week or less my neck had frozen solid, so my doctor got me back into the hospital to see the physio. And the first thing they said was, you shouldn’t be wearing that collar. So there is a conflict in there of information (B3577). This caused problems for informants who were then unsure about what treatment regimen to follow or who to believe. Most informants adopted the explanation for what was wrong which was tied to the most successful alleviation of symptoms. The attraction of complementary therapy (CAM): a pragmatic approach CAM was not usually the first port of call for treatment by informants, unless they had previous experience of their successful treatment of an earlier problem or their use was a result of lay referral. Informants who consulted CAM practitioners tended to adopt a pragmatic approach to their use: I had a chiropractor and at one point I was in so much pain I couldn’t do anything. It was straight across my shoulders and it even affected my breathing. My chest felt really tight I really was in a very bad way so that time he rubbed my shoulders and my back and the pain just went away it was incredible. It just really was so I would go and do that again but I certainly wouldn’t go to the doctor [again]. I don’t think the doctor could help or would help (I3127). Most informants who tried CAM did so by combining them with more conventional approaches, i.e. taking painkillers and attending for massage, reflexology or osteopathy. In these cases informants were searching for the approach that could best alleviate their pain: I have tried every treatment that is going bar going under the knife, which I don’t really wanna have to do. If I can get away with not going under the knife then I will try anything, and I tried acupuncture a little while ago (I2007). There was no sense in which a CAM approach was favoured on philosophical grounds or in terms of the holistic nature of the care process. Moreover, there were factors that boosted the position of orthodox medicine over CAM, particularly their accessibility to technology such as x-ray and MRI scans. Informants, however, saw no harm in dipping in and out of a variety of approaches: © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 332 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. I had just heard that it (a copper bracelet) was supposed to be good for, I don’t know if there is some property in copper whether they can seep into the skin and radiate, but I just read that it’s, and you see people with them and I thought I will give them a try (C293). As this quotation shows, many sufferers did not feel the need to understand what was involved or even believed in them, they were nevertheless willing to try them. This is perhaps one of the most striking things – the lengths to which informants would go in search of a cure. One woman who was an amateur musician in a local orchestra even talked of seeing a faith healer although she had no personal religious beliefs: I’d only go to him if I was in really serious pain and nothing else was helping, because I have a great belief in doctors and medicine . . . The reason I used it that one time was that you know, was that I just wanted to get through that particular performance and I wasn’t bothered (F2865). Some informants who had not tried complementary therapies would be willing to do so if they felt that practitioners were regulated in some way or even if they felt their GP advised it. These informants did not want to risk doing something that might later prove dangerous: I would actually like to look at alternative therapies, complementary therapies, I guess the difficulty is finding a practitioner who had a reputation, than look for something in the Yellow Pages, because I do see the standards of education and the level of student competence in some of the complementary therapies is more variable . . . I am more concerned that there might be a greater chance that there is somebody that is less well qualified, or less competent . . . And there is no question about it, that would make a difference to me, between going with confidence and going with apprehension (A3200). The financial outlay involved in seeing an alternative practitioner meant that it was only when the pain had become quite bad that the cost could be borne: Yes, be guided by the doctor or however for the best possible option, if it is recommended that I visit a chiropractor and it might cost a bit, I do have some healthcare insurance that does pay a proportion of the fee (A1262). Evaluating healthcare: the risks of orthodox medicines and benefits of dietary supplements Informants were ambivalent about the orthodox medications that were prescribed. They were given the choice of steroid injections or physiotherapy although steroids were often used as a quick solution for pain relief prior to getting access to physiotherapy. However, doubts were expressed about the value of steroids because of the fear of dependence and the uncertainty about their benefits. Similarly, informants were unhappy about the longterm use of painkillers, particularly non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and tried to avoid their use where possible. The fear of painkillers was based on the belief that they could be addictive: Some of the painkillers that I take are very, very strong and I only take them as and when I really, really need to because I just don’t wanna get hooked on them, and then © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 333 get addicted to them, but I try to manage without but then when it gets that bad I can’t (I2007). There was also the assumption that if the informant used analgesics too often, particularly in the early stages, when the symptoms got worse they would have nowhere left to turn. They would become immune to painkillers and there would be no other treatment available to them: I won’t take more painkillers, I could ask for more if I wanted but I don’t, I take one Ibuprofen a day because I have noticed that after a while they no longer work, the more you take the more you need and I don’t want to go down that road, . . . If I have got to be together I will take them if I have got something important to do. But the rest of the time I just live with it. I did have a TENS machine but I don’t think that that works terribly well, not for me anyway (A4324). Another major reason for trying to avoid painkillers, as with steroids, was the fear that masking the pain might do more harm in the long term. This was where the problems caused by lack of a clear diagnosis became most obvious. Because a number of informants did not know what was causing their upper limb problems they were fearful that their problems were possibly a sign of serious pathology. To take painkillers that would enable them to carry on as normal might have meant they were simply storing up trouble for themselves or even making things worse: Well I was wondering if it was anything more sinister than just an ache, and whether or not there was a diagnosis that could be made . . . I was seeking treatment in that respect, rather than just having pain control. I wanted to know the reason before I started taking the painkillers, it is all very well taking painkillers, but in the end you have got to treat the cause and not the symptoms (G2248). Dietary supplements were often used as an alternative form of pain relief. The most commonly used supplements being cod liver oil and glucosamine. Glucosamine, in particular, was held in high regard by informants and was considered by everyone who tried it to have given them some relief from pain. Although, again, they could not explain why they thought it worked: I was just out and about delivering flowers and I was delivering to this lady in this flat and I used to ask her how she was and she had just had a knee operation and a friend of hers took these tablets and she said if she had heard of them before she would have tried them before. So I asked her the name and I tried them; although they are expensive to buy they are brilliant (E2833). Many of the informants who took glucosamine did so on the advice of friends and based their decision to use it on anecdotal evidence. There was, however, some evidence that glucosamine had taken on the status of a prescribed drug. In some cases informants said that their GP had recommended it and others cited ‘scientific’ evidence: Eventually I happened to read an article in the Mail on Sunday on the health page about glucosamine sulphate and I thought, nothing ventured nothing gained you know. And I started doing that and at the time I did have a little pain in my knee, nothing much and © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 334 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. a little twinge in my ankle – nothing much, and literally within weeks that just went, but it took about a year before I had any real improvement in the arms, and since them it has been fine . . . as little as three or four years ago they were saying what a load of rubbish, they are not saying that any more, there has even been a write up in the Lancet about it and there is real proof now that it really is helpful, and it is regenerating worn out muscle tissue, and they are no longer dismissing it (E2389). Redefining the problem: invoking psychosocial explanations Initially the pain and other symptoms, including swelling and tingling, were understood by informants to be a result of some transitory biomechanical dysfunction, primarily resulting from wear and tear. When the symptoms failed to respond to treatment and persisted, or even got worse, then this understanding was called into question. The informant had to redefine their health problem from one that was transitory to one that was probably permanent. Once the condition became persistent and entered into a chronic state, the informants displayed a greater willingness to explore other explanations such as stress as a psychological factor in causing pain, although they tended to begin with an understanding of the physical aspects of stress: Well, yes, I think it does because your neck bunches up and the muscles tighten and I don’t think that helps. And yes any stress will exacerbate any sort of condition (A4324). Later on a more psychosocial understanding of stress was often introduced and informants who had been dealing with their condition for some time suggested that pain could be psychosomatic and realised that being anxious could make things worse: I had just sold my own cottage and it was just hideous what I went through, it took me about three years really, to even begin to even feel emotionally better. But as I got emotionally better, some of my aches and pains got much better as well. It’s only recently that I’m aware that it was a lot to do with stress. Its almost as if it ate away at me. And being shouted at was like being physically slapped (B3590). Informants who invoked stress as an explanation tended to do so as a result of a suggestion by the doctor or other healthcare worker: They always ask about stress, and I was with a very difficult partner. I was stressed most of the time, in fact when I went to the specialist he was asking about the stress in my life, and he sort of questioned me a wee bit, and he said I’m not a psychiatrist Mrs X but really this does not help your situation, and people said you’re so stressed all the time you need to get away . . . I wasn’t aware that stress could affect the body in that way (B3590). More commonly, informants were forced to come to terms with the impairment and the need to adapt to it by invoking the inevitability of ageing and the degeneration of the body that was expected to go with it. These informants eventually gave up on ‘bothering the doctor’ because they were convinced that there was nothing more that could be done for them: © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 335 Well they are not miracle workers, I mean yes I think they probably could have done more, but the state of the NHS, what I have got is not life threatening, it is very uncomfortable, but at the end of the day you have to accept that sometimes there are no cures. And they haven’t managed to do anything yet, I mean yes possibly one day something will come up and yes they will be able to sort it out (A4324). For informants who reached this stage the most common response was to undertake some programme of lifestyle change, usually involving stress management, dietary supplements and exercise. The changes that these informants made were usually relatively minor and were intended to enable them to continue living as normally as possible. When describing these changes no one described feeling particularly disturbed by them, instead their attitude was that anything that enables them to live normally can be accommodated: I just put up with the pain, you know when I went shopping, and I just came back with an aching arm. It doesn’t exactly stop me, I mean its only an ache, it didn’t stop me shopping, or it made me get my granny trolley, but I suppose in that way it changed my life, when I got my granny trolley (F2865). Managing and treating patients with ULDs: practitioners’ policies and practices Difficulties in diagnosis: diagnostic pragmatism Many conditions affecting the upper limb are relatively easily diagnosed and routine investigation such as blood tests and x-rays can reveal evidence of physical pathology, for instance tissue damage and rheumatoid arthritis. Other arm pain cases, however, are much more ambiguous and frequently difficult to diagnose accurately. Diagnostic tests are not always conclusive, and doctors often feel uncertain about the diagnostic category they have decided to use: You start questioning whether or not your diagnosis is correct and then it is difficult because you know sometimes, as I say, ‘there is not a diagnostic test to confirm your diagnosis’, but yeah it is difficult (4:7). The pragmatism of patients was also adopted by GPs in their approach to diagnosis and treatment. The costs involved in pursuing a specific diagnosis (for instance, costly diagnostic tests) were not warranted because treatment options were likely to be the same: I don’t think I often make a very firm diagnosis and I think I still manage them okay without. What I aim to do is differentiate the ones who need to go to physio, or the ones who need to go to orthopaedics, or the ones who will try a bit of anti-inflammatories for a while to see if they get better, or the ones, if the pain is a stress-related thing not musculoskeletal, then the ones that you have to look at that side of it, and I reckon as long as I can get them into those categories then I don’t need to actually put a name to it specifically (7:8). This pragmatic approach was shared by the hospital specialist: There are problems that are multi-functional in origin; they don’t have an easily identifiable basis. And if you can find ways of dealing with these problems then © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 336 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. we can skip the diagnosis. We think giving people a diagnostic label means so much and actually they mean nothing at all (17:38). The diagnostic label sometimes served an administrative function rather than a clinical one: It was the left wrist with what I described as artralgia of the wrist, because you have to pick a Read Code and it is quite difficult to get the right terminology because you have to pick a title. Practitioners, like patients, also favoured a biomechanical approach to explaining the disorder and were reluctant to attribute psychosocial labels even when there was no evidence of physical pathology. This was partly due to clinical uncertainty and the difficulty in ruling out physical pathology, but also that concern that the doctor-patient relationship might be harmed by refuting the patient’s claim that his or her arm pain is a biomechanical problem: If I felt that I couldn’t define a physical structural cause for ongoing discomfort then I would certainly start to tackle the psychological, but I would have to be quite sure that it wasn’t an orthopaedic, structural or rheumatological problem, before going down that road, because I think it would offend the patient and I think it would be bad medicine anyway (5:6). The practitioners were aware of the need to adopt a patient-oriented approach to their practice which involved listening, understanding and trying to achieve concordance between doctor and patient regarding cause, diagnosis, treatment and desired outcome. Most arm pain cases were presented as a biomechanical problem and the patient was often reluctant to accept a psychological interpretation of their complaint, not least because of the stigma attached to psychological problems. Hence, at least in the early stages of the treatment pathway, a biomechanical perspective was adopted without invalidating the patient’s claim that their problem was biomechanical: I think it is quite difficult for the patient to come to accept if you immediately dig into the psychological aspect as they tend to think you are dismissing it so I often tend to treat it as partly physical initially and then perhaps when I get to know them a bit more I will get into that side of it (9:4). Invoking psychosocial labels General practitioners, however, do use psychosocial labels in some contexts and this tends to be when treatments based on a biomechanical diagnosis have proven ineffective. The doctor, however, is faced with a problem in the use of a psychosocial label, as this may appear to contest the biomechanical validity of the patient’s complaint. Hence, various ‘smoothing’ strategies were used by doctors to introduce psychosocial explanations. The relationship was however seen as a form of ‘negotiation’ and doctors’ actions were also shaped by patients’ demands and interests. If patients resisted psychosocial explanations, GPs were required to employ ‘bridging technology’ to span the divide between biomechanical and psychosocial explanations. One such strategy entailed use of the label ‘Fibromyalgia’ which locates the illness in a biomechanical paradigm, but does not rely upon the identification of physical pathology and allows management of the condition to be addressed in terms of ‘coping’ rather than care. Many informants were sceptical about the status of Fibromyalgia as a legitimate disease category but it did enable GPs to treat the illness as psychosocial: © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 337 It is a bridge between the two isn’t it? Saying yes you have got physical symptoms and they are real. This is real pain and I believe you, and I am giving you a diagnosis (8:9). and Once I give that label it means I am ready to say to the patient, lets stop doing this and sending you to lots of different doctors looking for a cause, lets accept, if we can, that this is going on and now lets try and make you better (8:5.6). Practitioners also used stereotypes as a basis for describing a psychosocial explanation of arm pain. For example the socio-economic environment in which a practice is located established a frame of reference within which the origins and character of an illness can be located, i.e. social deprivation may lead to a psychosocial explanation. Attributes of the individual patient, for instance age and gender, could also lead to assumptions about the likelihood of a psychosocial or biomechanical explanation: . . . a 19-year-old boy who comes in with arm pain, you are thinking this is self-limiting and I may not even explore the psychological aspects and just give him some Ibuprofen and tell him it will get better (13:2). There was also a moral dimension in doctors’ appraisals, well illustrated in relation to work: A lot of people find it easier having a sick note saying shoulder pain rather than saying. . . . I mean there are some people who, one chap who had been off a long time with his shoulder problems and I think if he had a stronger work ethic, could have gone to work and for one reason or another could not . . . (6:16). Treatment strategies There was a high degree of homogeneity in the range of treatments employed for arm pain and the order in which they were deployed at different points in the treatment pathway. The first line of treatment usually entailed prescription of non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), such as Ibuprofen and/or analgesia often combined with rest. If this fails the second line of treatment was either a steroid injection, or if the patient resisted, referral to a physiotherapist. However, if this is unsuccessful, a referral is made to a hospital specialist at a pain clinic: I guess initially one tries simple things like analgesics and then we would look at other factors that might be interfering with them coping with the problem, and possibly consider the pain clinic, where they do look at people more holistically (9:17). The other options are re-diagnosis as a psychosocial problem in which case an antidepressant may be prescribed or consultation with a complementary therapist (CAM), which tended to be instigated by the patient rather than the doctor. Doctors supported some CAM treatment such as those provided by osteopaths and chiropractors and adopted an attitude of cautious tolerance in that they did appear to alleviate symptoms, and provided another treatment when orthodox treatment failed. However, there was a general reluctance to refer: © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 338 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. Principally because I think an osteopath and chiropractor lie outside the NHS and I have no absolute vindication of their professional status so I would be wary of referring. Patients may not see any difference (13:22). This cautious tolerance and reluctance to refer was based on doctors’ concerns about the effectiveness of CAM, its potential for harm and because it was in the private sector and was costly for patients who could not afford it. The other concern was about its theoretical basis and the manner in which it worked, for instance some informants felt that CAM achieved the amelioration of symptoms not by directly caring organic disease, but by manipulating the psychological aspects of illness and symptom tolerance. Some referred to the placebo effect or the effects that ‘pampering’ therapies could have on feelings of wellbeing. The amount of time that CAM therapists were able to spend with their clients was often felt to be central to this effect: I think it is more likely to be the placebo effect or, more importantly, what I think people would really like is sometimes people doing something that makes them feel good. Most of the people on this estate do nothing other than caring for other people, or, are working or on drugs and alcohol and nobody’s life is good if you have no time when you can spend half an hour that makes you feel good. And that is where complementary therapies fill the gap I think; I don’t know whether I brook the theory about homeopathy and stuff, but I don’t think it matters really (7:16). The case studies – pathways through healthcare Another perspective on the pathways followed by individual patients with upper limb pain was portrayed through the case studies constructed from the patient narratives, the practitioner’s accounts and the medical records. These provide further insight into how the different stages were linked together. It was not possible, at least from the particular case studies examined, to identify a typology of pathway, as each diverged at some stage. The cases clearly illustrate the nonlinear and negotiated nature of the process, the pragmatic approach to help seeking where pain management was a priority, the reluctance to consult due to the ‘normalisation’ of signs and symptoms (part of the ageing process), commuting between different types of practitioners and treatments and how patients assessed their perceived success or failure. What the case study methodology did specifically show, however, was the pathways out of care and the way practitioners and patients evaluated outcomes. The following three cases illustrate particularly how sometimes these perceptions of outcomes are divergent and sometimes convergent. Case A provided a typical example of the use of psychosocial explanations when the conventional treatments and biomechanical approach failed. It showed that the initial explanation used by both patients and practitioners emphasised physical, biomechanical dysfunction, primarily resulting from wear and tear. When the problems persisted or failed to respond to treatment, then this understanding was called into question. The informant had to redefine their problem from one that was transitory to one that was probably permanent. It clearly illustrated different perceptions of outcome. The GP felt that the musculoskeletal problems had been sorted out but the sufferer felt medicine had little to offer older people and those who had used self-medication to control the pain. In this case both patient and doctor were operating with entirely different models of her © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 339 condition. The GP highlighted the psychosocial aspects of the patient’s condition and believed that a referral to the CPN had resolved her psychological problems, and interpreted the fact that she had not been back to the surgery complaining of arm pain as a sign that this intervention was fully successful. The patient, on the other hand, was left with the impression that her arm pain could not be resolved via conventional medicine and persisted with self-treatment in the form of supplements. The patient was aware of her history of depression but understood this as entirely separate from her arm pain. Case B illustrated the different opinions of doctors about what was wrong and the use of different diagnostic labels. It clearly showed how sufferers used a range of different © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 340 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. practitioners and accepted the treatment which finally led to improvement. Once again, the lack of further use of a GP led the doctor to suggest that the patient’s condition had improved, which in this case was an accurate assumption. A similar approach was used by the GP in Case C although it was not accurate, as the sufferer, a reluctant consulter, adopted a strategy of accommodating the problem through the use of physical support and medication. The patient and the doctor clearly differed in their assessment of the encounter in that the patient felt that the doctor was hinting at the label ‘RSI’. The possible role of work in causation was raised by the doctor but resisted by the patient. Again there © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 341 was disagreement about outcome, with the patient still feeling incapacitated, and the GP suggesting that her non-consulting was a sign that things had improved. For her, the most important thing was to maintain a sense of normality, by adapting her behaviour at work to accommodate the pain she felt was unavoidable. Her priority was to manage that pain and alleviate its worst effects. © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 342 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. Discussion Upper limb pain was used in this paper as an example for shedding light on unanswered or under-researched questions in the study of illness action. It was selected because it appeared to embody the characteristics which could provide further insights into understanding patterns of illness action and help seeking. Those who have advocated the ‘illness career’ perspective (Uehara 2001) have argued that help-seeking can only be understood by looking at what has gone before, such as the recognition and interpretation of a problem. The methodology adopted in this study enabled the examination of the pathway into and out of care as it drew on sufferers and practitioners’ accounts and on case studies of individual pathways constructed from multiple sources of data. This illness career perspective has characterised the action process as a form of negotiation and this was evident in the pathways of people’s upper limb pain. This involved patients moving backwards and forwards between different healthcare practitioners. Beliefs and concepts of aetiology shifted over time in response to the experience of the consultation and treatment and to a variety of possible, yet potentially conflicting, explanations of the same condition. It clearly illustrated how ideas about causation were crucial, as others have consistently shown (Blaxter 2004) to understanding patterns of action and decisions to consult. The preferred explanation or idea about cause for both patients and practitioners was a physical or biomechanical explanation and psychosocial explanations were rarely and selectively invoked only when it was evident that a biomedical explanation could no longer be sustained. The patient’s preference for a physical or biomechanical explanation reflects the emphasis on self-management, the ‘normalisation’ of the problem in terms of routine illness, and that it is a legitimate problem to seek help for. Practitioners, particularly GPs, appeared to favour a biomechanical approach partly because of clinical uncertainty and the difficulty in ruling out physical pathology, but also because of concern that the doctor-patient relationship might be threatened by invalidating the patient’s claim that their arm pain was a biomechanical problem. Hence, the relationship was a negotiation or claimed to be and doctor’s actions appeared to be shaped by patient’s demands and interests. Smoothing strategies, such as the use of bridging technologies, were used which enabled GPs to treat the condition as psychosocial without invalidating the patient’s claim that the problem was biomechanical. The favoured ‘lay’ discourse of physiological ‘wear and tear’ and the ageing body was based on a machine metaphor of the body in which it was assumed that greater use of the arm is likely to make its mechanical components wear out quickly. It reflects a logic of degeneration in which illness follows the running down of the body and is a common finding in studies of musculoskeletal conditions (Sanders, Donovan and Dieppe 2002) and generally in lay theories of causation (Calnan 1987). Such ideas appear firmly embedded in current popular thinking although they may reflect the influence of medicalisation and medical, scientific ideas from previous generations rather than current scientific discourse. The latter emphasises work as a major cause or exacerbating factor. When work was invoked it was mainly seen in terms of exacerbating the condition and informants tended to take on the responsibility for their problem rather than placing the blame on their employers. There was little evidence of claims making (Arskey 1998), and work circumstances and relations seemed to constrain rather than enable help-seeking. Certainly, there appeared a resistance to labels such as RSI when attempts were made by practitioners to use them. However, it might be possible that this was a ‘generational’ rather than an ageing effect. Younger informants might be more aware of the influence of the working environment on their health than previous © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 343 generations because of policy changes such as the more recent increase in health and safety regulations. Theoretical approaches (Calnan 1987) shed only limited insights into the structure of decision-making in illness action. Lay decision-making in upper limb pain tended to be a long, drawn-out series of assessments, and accommodation to and self-management of problematic experiences, which were seen as part and parcel of ageing. Consultation with orthodox and non-orthodox practitioners was seen, at least initially, as inappropriate. This contrasts with conditions such as injuries and sudden illnesses (Calnan 1983, Ruston, Clayton and Calnan 1998) where decision-making was routine, brief and straightforward. The stages of identification that something was wrong, assessment of significance, and decision to act were all compressed into one process. The brevity of this process may have been influenced by the way signs imposed a ‘relevance’ onto the sufferer, although visibility and familiarity of the sign within a context, where cause was usually relatively easily attributed, enabled application of a lay diagnostic label to the disturbance. Upper limb pain sufferers rarely applied a lay diagnostic label and there was limited evidence of them searching for an acceptable diagnostic label. This stands in marked contrast to studies of repetitive strain (RSI) sufferers (Reid, Ewan and Lowy 1991) and chronic illness (Gerhardt 1989), which suggest that one of their major reasons for seeking help was for validation, acceptance and sympathy from their healthcare practitioner. Many did not receive a diagnosis and this did not appear particularly problematic, as it did not preclude the possibility of treatment. There was a general awareness that pain conditions were difficult to diagnose which explained, at least in part, the initial reluctance to seek help. The pragmatism of patients was also adopted by doctors in their approach to diagnosis and treatment, in that general practitioners also experienced doubts about whether the costs involved in pursuing a specific diagnosis were justified, as treatment options were likely to be the same. This provides a further illustration of how the encounter in general practice is, in this context, a ‘negotiated’ one where both actors seem to find a mutually acceptable outcome. The divergence in perceptions of outcomes, however, suggested that either the negotiation process or strategy between doctor and patient was not always adopted or it was sometimes unsuccessful. For example, the lack of further consultation was used as an indicator for healthcare practitioners that the condition would probably have improved but for patients it sometimes reflected that they thought orthodox and non-orthodox medicine had nothing further to offer and the most pragmatic approach was to self-treat and to accommodate to the problem. Thus, patients’ decisions to discontinue their involvement with formal healthcare was not, as some practitioners suggest, because of the success of the treatment but the opposite, i.e. a belief that orthodox and non-orthodox care had little more to offer. Certainly, lay evaluation of treatment and care was based primarily on pragmatic concerns, with the priority placed on alleviation of troublesome pain rather than the quality of the relationship with their practitioner. This search to find treatments that alleviate pain regularly involved the use of CAM practitioners, mainly osteopaths and chiropractors with dual usage between orthodox and CAM being the norm (Sharma 1995). Certainly, there was ambivalence about orthodox medical treatments and particularly about the long-term use of painkillers. This appears to reflect general concerns about the addictive nature of some medicines and drugs (Calnan, Montaner and Horne 2005). Thus, CAM treatments were attractive because they were seen to be safer, although there was little evidence that sufferers believed CAM was more effective than orthodox practice, and osteopaths and chiropractors tended to be evaluated in terms of a biomechanical model of the body. In contrast, medical professionals expressed ambivalence © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 344 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. about CAM practitioners because of altruistic concerns about exploitation of their patients and the possible harm of the treatment, although recognising that the treatment of osteopaths and chiropractors has shown to be beneficial for some of the patients. Thus, patients tended to instigate consultation with CAM practitioners themselves rather than being referred by their doctors. Finally, the topic of illness behaviour appears to have re-emerged or has been ‘rediscovered’ mainly in the context of the ‘problem’ of variations in the use of and provision of services for people with mental health and ‘contested’ illnesses. From a sociological point of view these ‘new’ theoretical perspectives have attempted to synthesise and build on previous frameworks to address the possible influence of structure on the course of illness action as well as attempt to eliminate the artificial dichotomy between the quantitative and qualitative traditions. The concept of social network appears central to these theoretical approaches, and there was evidence in this case study to show how it may influence the interpretive work and decision-making of the sufferer. Pathways to care, at least followed by people with mental health problems (Pescosolido, Brooks Gardner and Lubell 1998) have been shown to reflect a process of ‘muddling through’. Similarly, pathways for sufferers with upper limb pain were divergent and non-linear but were best described as ‘opportunistic’ with patients making use of opportunities which were available and accessible. These ‘opportunistic’ pathways and patterns of illness action seemed to be enabled and constrained by beliefs and experience. These included beliefs about cause, about when and what to seek help for and about the benefits and dangers of treatments. However, these beliefs and knowledge were, in part, a product of formal and informal contacts with others, and thus social networks may structure patterns of action through providing stories and stocks of knowledge about what to do and who and where to seek help from. This suggests the need to explore further how structures for action are embedded in and emerge from people’s accounts and narratives of health and illness. Address for correspondence: M. Calnan, MRC HSRC, Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol, Canynge Hall, Whiteladies Road, Bristol BS8 2PR e-mail: m.w.calnan@bristol.ac.uk Acknowledgments This study was funded by a grant from the MRC HSRC. We are grateful to the MRC Unit at Southampton University for use of their survey questions on upper limb pain and their nurse examination assessment. Thanks also to the two anonymous reviewers and members of the editorial team for their constructive comments on earlier drafts. References Adamson, C. (1997) Existential and clinical uncertainty in the medical encounter, Sociology of Health and Illness, 19, 2, 133 –59. Aldrich, S., Eccleston, C. and Crombie, G. (2000) Worrying about chronic pain, Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 457–70. Alonzo, A. (1984) An illness behaviour paradigm: a conceptual exploration of a situational adoption perspective, Social Science and Medicine, 19, 499 –510. Arskey, H. (1998) RSI and the Experts. London: UCL press. Blaxter, M. (2004) Health: Key Concepts. Cambridge: Polity Press. © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd Illness action and upper limb pain 345 Bongers, P. (2001) The cost of shoulder pain at work, British Medical Journal, 322, 64–5. Britten, N. (1995) Qualitative interviews in medical research, British Medical Journal, 311, 251–3. Calnan, M. (1983) Managing minor disorders: pathways to a hospital accident and emergency department, Sociology of Health and Illness, 5, 149–67. Calnan, M. (1987) Health and Illness: the Lay Perspective. London: Tavistock. Calnan, M., Montaner, D. and Horne, R. (2005) How acceptable are innovative health-care technologies? A survey of public beliefs and attitudes in England and Wales, Social Science and Medicine, 60, 1937– 48. Canaan, J. (1999) In the Hand or in the Head? Contexualising the Debate about Repetitive Strain Injury. In Daykin, N. and Doyal, L. (eds) Health and Work: Critical Perspectives. London: St Martins Press. Carpenter, N. and Ducharme, F. (2005) Support network transformations in the first stages of the caregivers career, Qualitative Health Research, 15, 3, 289–311. Charmaz, K. (2000) Experiencing chronic illness. In Albrecht, G., Fitzpatrick, R. and Scrimshaw, A. (eds) The Handbook of Social Studies in Health and Medicine. London: Sage. Coggon, D., Palmer, K. and Walker-Bone, K. (2000) Occupation and upper limb disorders, Rheumatology, 39, 1057–9. Cornwell, J. (1984) Hard-earned Lives. London: Tavistock. Cowie, W. (1976) The cardiac patients perception of his heart attack, Social Science and Medicine, 10, 87–96. Dingwall, R. (1976) Aspects of Illness. London: Martin Robertson. Fabrega, H. (1974) Disease and Social Behaviour. Boston, Mass: MIT Press. Gerhardt, U. (1989) Ideas about Illness. An Intellectual and Political History of Medical Sociology. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd. Heilstrom, C. (2001) Affecting the future: chronic pain and perceived agency in a clinical setting, Time and Society, 10, 1, 77–92. Lawton, J. (2003) Lay experiences of health and illness: past research and future agendas, Sociology of Health and Illness, 25, 23 – 40. Macfarlane, G., Hunt, I. and Silman, A. (2000) Risk of mechanical and psychosocial factors in the onset of forearm pain: prospective population based study, British Medical Journal, 321, 7262, 676 – 9. May, M., Doyle, H. and Chew-Graham, C. (1999) Medical knowledge and the intractable patient: the case of chronic low back pain, Social Science and Medicine, 48, 4, 523–34. Mckinlay, J. (1972) Some approaches and problems in the study of the use of services – an overview, Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 13, 115, 29–46. Mechanic, D. (1968) Medical Sociology. New York: Free Press. Mechanic, D. and Angel, R. (1987) Some factors associated with the report and evaluation of back pain, Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 28, 131–9. Nettleton, S., Osmalley, L., Watt, I. and Duffey, P. (2004) Enigmatic illness, Social Theory and Health, 2, 47– 66. NIOSH (1997) Musculoskeletal Disorder and Workplace Factors: a Critical Review of Epidemiological Evidence for Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Neck, Upper Extremity and Lower Back. Ohio: DHHS (NIOSH). Palmer, K. and Cooper, C. (2000) Repeated movement and repeated trauma affecting the musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limbs. In Baxter, P., Adams, P., Aw, T-C. et al. (eds) Hunter’s Diseases of Occupations (9th Edition). London: Arnold. Palmer, K., Walker-Bone, K., Linaker, C., Reading, I., Kellingray, S. and Coggon, D. (2000) The Southampton examinations schedule for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limbs, Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, 59, 1, 5 –11. Panel on Musculoskeletal Disorders (2001) Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace. National Research Council: Institute of Medicine. Paterson, C. and Britten, N. (1999) Doctors can’t help much: the search for an alternative, British Journal of General Practice, 49, 626 –9. Pescosolido, B. (1991) Illness careers and network ties: a conceptual model of utilization and compliance, Advances in Medical Sociology, 2, 161–84. © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 346 M. Calnan, D. Wainwright, C. O’Neill et al. Pescosolido, B. (1992) Beyond rational choice: the social dynamics of how people seek help, American Journal of Sociology, 97, 4, 1096 –138. Pescosolido, B. (1996) Building the community into utilisation models, Research into the Sociology of Health Care, 13A, 171–97. Pescosolido, B. and Boyer, C. (1996) From the Community into the Treatment System – how People use Health Services. In Horwitz, A. and Scheid, T. (eds) The Sociology of Mental Illness. New York: Oxford University Press. Pescosolido, B., Brooks Gardner, C. and Lubell, K.M. (1998) How people get into mental health services: stories of choice, coercion and muddling through from first-timers, Social Science and Medicine, 46, 2, 275 – 86. Pescosolido, B. and Wright, E.R. (2004) The view from two worlds: the convergence of social network reports between mental health clients and their ties, Social Science and Medicine, 58, 1795–806. Reid, J., Ewan, C. and Lowy, E. (1991) Pilgrimage of pain: the illness experience of women with repetitive strain injury and the search for credibility, Social Science and Medicine, 32, 5, 601–12. Rhodes, L., McPhillips-Tangum, C., Markham, C. and Klenk, R. (1999) The power of the visible: the meaning of diagnostic tests in chronic back pain, Social Science and Medicine, 49, 9, 1189–203. Robinson, D. (1971) The Process of Becoming Ill. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Rogers, A. and Elliott, H. (1997) Understanding Health Need and Demand, NPCRCD Series Abingdon, Oxon: Radcliffe Medical Press. Ruston, A.M., Clayton, J. and Calnan, M. (1998) Patients’ actions during their cardiac events – qualitative study exploring differences and modifiable factors, British Medical Journal, 316, 1060–65. Sanders, C., Donovan, J. and Dieppe, P. (2002) The significance and consequences of having painful and disabled joints in older age: co-existing account of normal and disrupted biographies, Sociology of Health and Illness, 24, 227–53. Sharma, U. (1995) Using Complementary Therapies: a Challenge ot Orthodox Medicine? In Williams, S. and Calnan, M. (eds) Modern Medicine: Lay Perspectives and Experiences. London: UCL press. Strauss, A. (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage. Summerfield, D. (2001) The invention of post-traumatic stress disorder and the social usefulness of a psychiatric category, British Medical Journal, 322, 95–98. Thomas, K., Carr, J., Westlake, L. and Williams, B. (1991) Use of non-orthodox health care in Great Britain, British Medical Journal, 302, 207–10. Uehara, E. (2001) Understanding the dynamics of illness and help-seeking, Social Science and Medicine, 52, 519 –36. Young, J. (2004) Illness behaviour: a selective review and synthesis, Sociology of Health and Illness, 26, 1, 1 –31. Zola, I. (1973) Pathways to the doctor – from person to patient, Social Science and Medicine, 7, 677–89. © 2007 The Authors Journal compilation © 2007 Foundation for the Sociology of Health & Illness/Blackwell Publishing Ltd