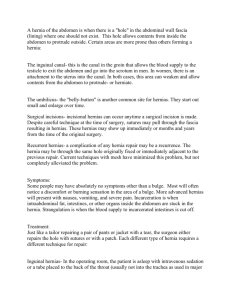

Hernia (2004) 8: 104–107 DOI 10.1007/s10029-003-0182-5 O R I GI N A L A R T IC L E M. Kurzer Æ P.A. Belsham Æ A.E. Kark Tension-free mesh repair of umbilical hernia as a day case using local anaesthesia Received: 7 February 2003 / Accepted: 2 October 2003 / Published online: 13 March 2004 Springer-Verlag 2004 Abstract Background: Umbilical hernias are a common surgical problem with a high recurrence rate using conventional suture techniques. This prospective study examined the feasibility of tension-free mesh repair as a day case using local anaesthetic (LA) for all primary umbilical hernias. Method: Fifty-four patients (eight women) were operated on; 49 using LA. Through a periumbilical skin incision the margins of the sac were freed from the edges of the defect, and a space was made in the extraperitoneal plane. In defects <3 cm in diameter, a cone of polypropylene (pp) mesh was inserted and attached with nonabsorbable sutures. In defects >3 cm, a flat piece of pp mesh was inserted into the extraperitoneal space as a sublay. No attempt was made to close the fascial defect. Results: Postoperative pain was graded as mild (n=37) and moderate (n=17). No patient had severe postoperative pain. Seven superficial wound infections responded to oral antibiotics. In no case it was necessary to remove the mesh. There were no other complications. Patients were recalled between 2 and 6 years postopertively—mean follow-up 43 months (28–67). There were no recurrences. Conclusion: Umbilical hernia repair can be carried out safely and securely under LA with a tension-free mesh technique (cone or a sublay patch) with a low morbidity, negligible recurrence rate, and a high degree of patient satisfaction. It should be the procedure of choice for all such hernias. Keywords Umbilical hernia Æ Day-case surgery Æ Ambulatory surgery Æ Local anaesthesia Æ Surgical mesh Æ Treatment outcome Introduction Umbilical hernias in adults are a common surgical problem with wide variation in techniques of repair and results [1, 2]. Recurrence rates as high as 40% using conventional sutured techniques have been reported [3], although there are sparse data in the literature [4]. Prosthetic mesh is now widely and routinely used for many abdominal wall hernias and virtually all inguinal hernias. This study examined the feasibility, results, and medium-term follow-up of tension-free mesh repair for adult umbilical hernia repair. Patient and methods Over a 38-month period between August 1995 and November 1998, 73 patients with an umbilical hernia were seen. Eight patients had a BMI (Body Mass Index) greater than 40, were advised to lose weight, and were not operated on. Patients with a recurrent hernia were considered to present a complex surgical problem and were also not included in this study. In all, 19 patients were excluded, and 54 patients with a primary umbilical hernia were entered into the study. The majority (49) of patients were ASA 1 or 2, and the mean BMI was 31 (22–39.5). The mean age was 52 years (range 30–76), eight patients were women. No patients had liver failure. In 49 patients, the procedure was carried out using local anaesthesia with an anaesthetist present to monitor and administer sedation. In five patients, the procedure was carried out using general anaesthetic; one because of patient preference, two because of the size of the hernia, and two because of the size of the patient (BMI>35). Operative technique Presented to the 24th International Congress of the European Hernia Society, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, June 2002 M. Kurzer (&) Æ P.A. Belsham Æ A.E. Kark British Hernia Centre, 87 Watford Way, NW4 4RS London, U.K. E-mail: surgeons@hernia.org Tel.: +44-020-82017000 Fax: +44-020-82026714 A broad spectrum antibiotic was given at the start of the procedure, and the local anaesthetic used was 0.25% bupivacaine plain. Midazolam up to a maximum of 10 mg iv was administered by the anaesthetist as appropriate. Through a hemicircumferential periumbilical skin incision, the margins of the sac were freed from the edges of the defect, and a space was made in the extraperitoneal plane beneath the rectus sheath. In defects <3 cm in diameter, a cone of polypropylene mesh was made by the operating surgeon from a 5 cm·5 cm square of polypropylene mesh of such a size that diameter of the cone was 105 no recurrences, and all patients felt that the appearance of the umbilicus was cosmetically acceptable. Discussion Fig. 1 Cone-shaped plug made from a square piece of mesh and a single nonabsorbable suture slightly greater than the size of the defect (Fig. 1). The cone was inserted so that the rim lay just beneath the edges of the defect, and four 2/0 polypropylene sutures were inserted at the four quadrants of the defect to anchor it. In defects >3 cm in diameter, a flat piece of polypropylene mesh was shaped so that its diameter was approximately 5 cm–6 cm greater than the diameter of the defect (there was at least a 2.5–3 cm overlap all round) and was inserted into the extraperitoneal space and held in place with polypropylene sutures. Four sutures were inserted initially and additional sutures as appropriate. No attempt was made to close the fascial defect. If there was a large remaining dead space, a vacuum drain was inserted. The umbilical skin was attached to the fascia or anterior rectus sheath in order to reconstitute the umbilical depression and the incision closed with an absorbable subcuticular suture. In larger hernias, a vacuum drain was inserted and was removed just prior to discharge. A pressure dressing was used in all cases. Seven patients with particularly large hernias in whom a vacuum drain had been inserted remained in hospital overnight for observation. The remainder were discharged the same day. Postoperative pain was controlled with oral analgesics supplemented by self-administered diclofenac suppositories. Patients went home with detailed postoperative instructions and a 24-hour contact number. Patients were asked to grade their pain using a visual analogue scale on the second postoperative day. Results Postoperative pain on the second postoperative day was graded by patients as mild (n=37) and moderate (n=17). No patient had severe postoperative pain. Patients were seen at 1 week for follow-up and removal of dressing. There were seven superficial wound infections, and all responded to appropriate oral antibiotics. In no case it was necessary to remove the mesh, and there were no other complications. Patients were recalled between 2 and 6 years postoperatively—mean followup 43 months (28–67). Forty-four patients were reassessed, and ten patients were lost to follow-up. There were The reported results of umbilical hernia repair vary widely. While some claim that simple suture and a combined closure of peritoneum and fascia yields good results [5, 6], these reports are anecdotal. Recurrence rates as high as 40% [3], rising to 60% in patients with cirrhosis [7], have been reported. More recent studies have revealed recurrence rates of 11% [8] and 15% [2] for sutured repair. Askar [3] has highlighted how physiologically unsound the sutured repair is, particularly with large or recurrent defects. Failure of the treatment of hernia defects is almost certainly due to excessive tension [9], and while various manoeuvres have been proposed to lessen tension when repairing large umbilical hernias, they are all technically complex. A sublay (placement beneath the rectus muscle) of prosthetic mesh achieves a tension-free repair much more simply and reliably and has been employed with great success in incisional hernia [10] and in a small series of umbilical hernias in cirrhotic patients [11], both known to be at high risk of recurrence and morbidity. The recurrence rate of 0 in this series, with a follow-up period of up to 6 years represents a significant improvement over nonmesh repairs and is in line with the findings of other authors using prosthetic mesh [4, 8, 12] Garcia-Urena [2] retrospectively reviewed the charts of 101 patients who had undergone urgent repair of an incarcerated umbilical hernia. They were able to contact and reassess 80 of the patients and found a recurrence rate of 15% with a mean follow-up of 7 years. The majority of patients had undergone some form of suture repair, but, interestingly, in the three in whom mesh had been used, there was no recurrence. Celdran [12] reported no recurrences using mesh in 21 cases with a relatively short follow-up of 13 months. Because of difficulties in developing a preperitoneal plane, an H-shaped piece of mesh was used, part of which was placed intraperitoneally with omentum interposed to separate the mesh from bowel. However, in the present study, we found, similarly to Arroyo, that we were able to make an adequate space in the preperitoneal plane (with defects >2.5 cm in diameter), although it required careful and meticulous sharp dissection. The decision whether to use a flat piece of mesh or a cone in this series was a pragmatic one. Accurate placement and positioning of a flat piece of mesh through a 3.0 aperture was found to be difficult, and the authors were reluctant to enlarge the defect in order to facilitate this. Insertion of a small cone to fill the defect proved to be a straightforward solution. Mesh cones or plugs have been used successfully in a similar way in the repair of primary indirect, femoral, and recurrent groin hernias [13, 14]. Theoretical fears that the cone might 106 shrink, giving rise to local discomfort or recurrence would seem to be without foundation. Bowley and Kingsnorth [15] retrospectively reviewed the case notes on 473 primary adult umbilical hernias operated on over a 5-year period by a number of surgeons in a large hospital, using various techniques. During the period of study, 18 patients were reoperated on for recurence. However, the remaining 455 patients were not contacted for review, so we cannot assess the overall recurrence rate. Of the 18 known patients whose hernias recurred, two out of 80 (4%) were open mesh repairs, and 16 out of 393 (2.5%) were nonmesh. The only randomised clinical trial of umbilical hernia repair in the world literature is that of Arroyo and colleagues [8]. Two hundred patients were randomised to receive mesh or simple suture, mostly (95%) under local anaesthesia. The mean follow-up was 64 months, and there was a ten-fold difference in recurrence rates (1% vs 11%) comparing suture with mesh repair. This group subsequently reported on 213 patients with umbilical hernia repaired with polypropylene mesh [4]. Complications were minimal, and the recurrence rate at 64 months was 0.95%. We also found the use of local anaesthesia in this situation to be feasible, and it meant that cardiac, respiratory, and thrombotic complications did not occur. Patients were able to walk immediately, and there was no nausea or vomiting. The majority of general surgeons still seem reluctant to employ local anaesthesia despite evidence of its efficacy in terms of patient safety, comfort, and overall cost [8, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]. Despite using prophylactic antibiotics in the present series, 7% of patients developed a superficial infection postoperatively, characterised by local tenderness and redness of the skin. No patient had a purulent discharge or evidence of deep infection. All responded to antibiotics, and no mesh required removal. Umbilical hernias seem to be at greater risk of developing a wound infection than groin hernias. Abramov found a 33% incidence of wound infection [23], possible reasons being the poorly vascularised thin skin flap and the intrinsic bacterial colonisation of the area. Some have cautioned against the indiscriminate use of prosthetic mesh for umbilical hernia repairs because of fears of infection [24]. However, reported wound infection rates vary widely. Arroyo found an incidence of wound infection of 2–3% [8] and 1.4% [4], while Celdran reported no wound infections at all in his series consisting only of mesh repairs [12]. In Garcia-Urena’s study [2] (all nonmesh repairs) 18% developed a wound infection, the commonest complication. In contrast to inguinal hernia repair, prophylactic antibiotics should be given routinely in umbilical hernia repair. If a postoperative infection does occur, it would appear to be readily treatable with appropriate antibiotics. Laparoscopic repair of umbilical hernia has also been advocated. Nguyen reported what was essentially a feasibility study of a small series of small hernias repaired laparoscopically by suturing [25]. No compli- cations were reported in this group of 16 patients, followed up for only 5 months. Wright and colleagues [26] retrospectively reviewed 112 patients who had undergone umbilical hernia repair with one of three techniques: open operation without mesh, open with mesh, or laparoscopic. Open without mesh had the highest incidence of recurrence and the highest rate of complications. In 75% of the open mesh repairs, the technique was fascial closure plus onlay mesh—not a true tensionfree sublay technique. Nevertheless, both types of mesh repair had comparable recurrence and complication rates, although operative time and length of hospital stay was less in the open mesh group. Thus laparoscopic repair requires an obligatory general anaesthetic, and all that that entails in terms of staff, equipment, safety, and cost [27, 28, 29]. There is also the creation of additional potential defects at port sites and the need to place mesh intraperitoneally [30]. While advocates of laparoscopic groin hernia repair claim reduced postoperative discomfort to offset these disadvantages, this benefit has not been demonstrated with primary umbilical hernia repair. The present study, along with others [8], has demonstrated the effectiveness with which this type of hernia can be repaired using an open approach and local anaesthetic, with high patient acceptance, low morbidity, and a very low (in this series 0) recurrence rate. Conclusion This straightforward open technique of placing ‘tensionfree’ mesh in a sub-fascial plane is applicable to all umbilical hernias with minimal morbidity and an extremely low incidence of recurrence. The procedure is admirably suited to the use of local anaesthesia and ambulatory surgery in the majority of patients. Acknowledgements Cone drawn by K. Daly, Dept. of Medical Illustration, Royal Free Hospital, London, U.K. References 1. Velasco M, Garcia-Urena M, Hidalgo M, Vega M, Carnero F (1999) Current concepts on adult umbilical hernia. Hernia 4:233–239 2. Garcia-Urena M, Rico P, Seoane J, et al. (1994) Hernia umbilical del adulto. Cir Espanol 56:302–306 3. Askar OM (1978) A new concept of the aetiology and surgical repair of paraumbilical and epigastric hernias. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 60:42–48 4. Arroyo A, Perez F, Serrano P, Costa D, Oliver I, Ferrer R, Lacueva J, Calpena R (2002) Is prosthetic umbilical hernia repair bound to replace primary herniorrhaphy in the adult patient? Hernia 6:175–177 5. Farris J, Smith G, Beattie A (1959) Umbilical hernia: an inquiry into the principle of imbrication and a note on the preservation of the umbilical dimple. Am J Surg 98:236–242 6. Pollak R, Nyhus L (1984–5) Umbilical hernia repair. In: Cameron, J (ed) Current Surgical Therapy. BC Decker, Philadelphia, p 284 107 7. Belghiti J, Durand F (1997) Abdominal wall hernias in the setting of cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis 17:219–226 8. Arroyo A, Garcia P, Perez F, Andreu J, Candela F, Calpena R (2001) Randomized clinical trial comparing suture and mesh repair of umbilical hernia in adults. Br J Surg 88:1321–1323 9. Nahas FX, Ishida J, Gemperli R, Ferreira MC (1998) Abdominal wall closure after selective aponeurotic incision and undermining. Ann Plast Surg 41:606–617 10. Rives J, Pire J, Flament J, Palot J, Body C (1985) Le traitement des grandes eventrations. Nouvelles indications therapeutiques a propos de 322 cas. Chirurgie 111:215-225 11. Gutierrez de la Pena C, Fakih F, Marquez R, DominguezAdame E, Garcia F, Medina J (2000) Umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients: a safe approach. Eur J Surg 166:415–416 12. Celdran A, Bazire P, Garcia-Urena MA, Marijuan JL (1995) H-hernioplasty: a tension-free repair for umbilical hernia. Br J Surg 82:371–372 13. Shulman AG, Amid PK, Lichtenstein I (1990) The ‘plug’ repair of 1402 recurrent inguinal hernias. Arch Surg 125:265–267 14. Robbins AW, Rutkow IM (1998) Mesh plug repair and groin hernia surgery. Surg Clin North Am 78:1007–1024 15. Bowley D, Kingsnorth A (2000) Umbilical hernia, Mayo or mesh? Hernia 4:195–196 16. Deysine M (2000) Umbilical Hernias In: Bendavid, R (ed) Abdominal Wall Hernias, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 680–684 17. Young DV (1987) Comparison of local, spinal and general anesthesia for inguinal herniorrhaphy. Am J Surg 153:560–563 18. Terranova O, deSantis L, Battochio F (2000) Local Anesthesia In: Bendavid, R (ed) Abdominal Wall Hernias, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 317–323 19. Behnia R, Hashemi F, Stryker SJ (1992) A comparison of general versus local anesthesia during inguinal herniorrhaphy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 174:277–280 20. Britton BJ, Morris PJ (1984) Local anesthetic hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am 64:245–255 21. Gianetta E, de Cian F, Cuneo S, Friedman D, Vitale B, Marinari G, Baschieri G, Camerini G (1997) Hernia repair in elderly patients. Br J Surg 84:983–985 22. Paajanen H (2001) Lichtenstein inguinal herniorraphy under local infiltration anaesthesia as rapid outpatient procedure. Ann Chir Gynaecol 90:51–54 23. Abramov D, Jeroukhimov I, Yinnon AM, Abramov Y, Avissar E, Jerasy Z, Lernau O (1996) Antibiotic prophylaxis in umbilical and incisional hernia repair: a prospective randomised study. Eur J Surg 162:945–948 24. Chant H, Tsai P, Kingsnorth A (2001) Randomized clinical trial comparing suture and mesh repair of umbilical hernia in adults. Br J Surg 88:1321–1323 25. Nguyen NT, Lee SL, Mayer KL, Furdui GL, Ho HS (2000) Laparoscopic umbilical herniorrhaphy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 10:151–153 26. Wright BE, Beckerman J, Cohen M, Cumming JK, Rodriguez JL (2002) Is laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair with mesh a reasonable alternative to conventional repair? Am J Surg 184:505-508 27. Arvidsson D, Smedberg S (2000) Laparoscopic compared with open hernia surgery: Complications, recurrences and current trends. Eur J Surg 585:40–47 28. Cunningham A (1998) Anesthetic implications of laparoscopic surgery. Yale J Biol Med 71:551–578 29. Phillips EH, Arregui ME, Carroll BJ, et al. (1995) Incidence of complications following laparoscopic hernioplasty. Surg Endosc 9:16–21 30. Coda A, Bossotti M, Ferri F, Mattio R, Ramellini G, Poma A, Quaglino F, Filippa C, Bona A (2000) Incisional hernia and fascial defect following laparoscopic surgery. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 10:34–38