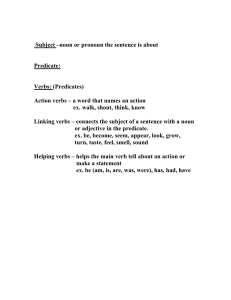

The Artful Sentence 1: Active Subjects A Sentence-Level Style Unit by Constance Hale; Arranged by M.J. Boswell “For surely it is a magical thing for a handful of words, artfully arranged, to stop time.” – Jhumpa Lahiri At some point in our lives, early on, maybe in grade school, teachers give us a pat definition for a sentence — “It begins with a capital letter, ends with a period and expresses a complete thought.” We eventually learn that that period might be replaced by another strong stop, like a question mark or an exclamation point. But that definition misses the essence of sentencehood. We are taught about the sentence from the outside in, about the punctuation first, rather than the essential components. The meaning of our every utterance, is given form by nouns and verbs. To use a boat metaphor: Nouns give us sentence subjects — the hull on which the rest of the boat is built. Verbs give us predicates — the boat’s forward momentum, the twists and turns, the abrupt stops. For a sentence to be a sentence we need a What (the subject) and a So What (the predicate). The subject is the person, place, thing or idea we want to express something about; the predicate expresses the action, condition or effect of that subject. Think of the predicate as a predicament — the situation the subject is in. I like to think of the whole sentence as a mini-narrative. It features a protagonist (the subject) and some sort of drama (the predicate): The searchlight sweeps. Harvey keeps on keeping on. The drama makes us pay attention. Let’s look at some opening lines of great novels to see how the sentence drama plays out. Notice the subject, in bold, in each of the following sentences. It might be a simple noun or pronoun, a noun modified by an adjective or two or something even more complicated: 1. “They shoot the white girl first.” — Toni Morrison, “Paradise” 2. “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed.” — James Joyce, “Ulysses” 3. “Saint Rufina, a famous woman who had been a very lovely young princess with long black hair who decided to give up her jewelry and become a nun and wear only the roughest clothes, and who died in a terrible way, by being eaten to death by wild dogs that ran through the church in the dead of wintertime, was in a special chapel all to herself, where one arm of her was set aside, that someone had scooped up and saved from the dogs, because everyone had loved her for her kindness and her healing ability.” –Nicholson Baker, “The Everlasting Story of Nori: A Novel” Switching to the predicate, remember that it is everything that is not the subject. In addition to the verb, it can contain direct objects, indirect objects, adverbs and various kinds of phrases. More important, the predicate names the predicament of the subject. 4. “Elmer Gantry was drunk.” — Sinclair Lewis, “Elmer Gantry” 5. “Every summer Lin Kong returned to Goose Village to divorce his wife, Shuyu.” — Ha Jin, “Waiting” There are variations, of course. Sometimes the subject is implied rather than stated, especially when the writer uses the imperative mood: 6. “Call me Ishmael.” — Herman Melville, “Moby Dick” And sometimes there is more than one subject-predicate pairing within a sentence: 7. “We started dying before the snow, and like the snow, we continued to fall.” — Louise Erdrich, “Tracks” Understanding the relationship between the hull and the sail, the What and the So What, is the first step in mastering the dynamics of a sentence. ACTIVE SUBJECTS EXERCISE 1: Directions: One way to get the hang of such mini-narratives is to gently imitate great oneliners. Try taking each one of the sentences above and plugging in your own subjects and predicates, just to sense the way that nouns and verbs form little stories. Submit your version to Google Classroom. Your version of #1: Your version of #2: Your version of #3: Your version of #4: Your version of #5: Your version of #6: Your version of #7: ACTIVE SUBJECTS EXERCISE #2: Directions: The following sentences are poorly focused, using either weak subjects or verbs, or both. Rewrite these sentences using more concrete subjects and/or more active verbs. EXAMPLES: A. Weak: My reason for missing the appointment was because I couldn't find the doctor's office. Better: I missed the appointment because I couldn't find the doctor's office. B. Weak: There were two actions, which could have been taken by us. Better: We could have taken two actions. YOUR TURN: 1. Something every person needs is a high degree of self-confidence. 2. It is obvious that there should be more courses in the humanities taken by the average student. 3. In the process of planning his major, the result he hoped to achieve after graduating was getting a good job with a good salary. 4. The reason for the confusion of most people about the new tax-reform proposals is that they are written in legalese, language only lawyers understand. 5. It was when I was waiting in line at the DMV that the realization came to me of how complex dealing with a major bureaucracy is. 6. Her long-winded and unclear sentences have been replaced by succinct, sparkling prose. 7. In an ideal society, creating a sense of belonging would be looked upon highly by its citizens. 8. What Cristina Garcia’s main character, Suki Palacios from The Lady Matador’s Hotel, is trying to prove is that women, young women even, can exert exacting control and power over formidable opposition.