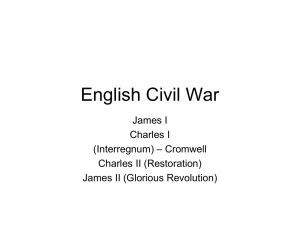

1. The Protestant Reformation (1517-1648) questioned the authority of the Catholic Church, and by extension, nearly every repository of central authority. 2. The Parliaments of 1563 and 1566-67 were active in petitioning Elizabeth to announce a successor and marry (a matter of foreign policy). In 1566 the commons attempted to postpone the Queen's request for money until she had satisfied their grievances, but Elizabeth managed to outmaneuver them. In 1587, Parliament pushed for Elizabeth to accept the sovereignty of the Netherlands, but the queen refused again. In short, during Elizabeth’s 45 year reign, Parliament was in session for a total of 140 weeks. The magnitude of England’s substantial debt racked up through repeated wars against Catholic Spain may be viewed as a measure of Parliament’s weakness. This debt constrained both James I and Charles I. 3. Educational and political consciousness evolved during Elizabeth’s rule. Local gentlemen elected to the House of Commons elevated how well Parliament worked and created an "institutional memory" by improving Parliament’s records and establishing precedents. By 1620, Parliament was quite capable. 4. The Hampton Court Conference of 1604 between James I and his bishops addressed Puritan complaints about the Catholic terms Absolution and Confirmation. The outcome pleased both the King and Puritans: intermediaries between God’s word and man were eliminated and King James commissioned an updated translation of the bible, which became the King James Version used today. 5. Authorities foil Guy Fawkes’ Gunpowder Plot of 1605, leading many to rally round King James and England. Spring 2014 MWH-1AS Charles I execution—Source A Significance page 1 6. James I to Parliament, 21 March, 1610: “Kings are justly called Gods, for if you will consider the Attributes to God, you shall see how they agree in the person of a King. God hath power to create, or destroy, make, or unmake at his pleasure, to give life, or send death, to judge all, and to be judged nor accountable to none: To raise low things, and to make high things low at his pleasure, and to God are both soul and body due. And the like power have Kings: they make and unmake their subjects: they have power of raising, and casting down: of life, and of death: Judges over all their subjects, and in all causes, and yet accountable to none but God only. They have power to exalt low things, and abase high things, and make of their subjects like men at the Chess; A pawn to take a Bishop or a Knight, and to cry up, or down any of their subjects, as they do their money. And to the King is due both the affection of the soul, and the service of the body of his subjects.” http://faculty.history.wisc.edu/sommerville/351/Jamesdrk.htm 7. During the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War in 1618, James I hesitated to send English troops to the aid of German Protestants battling German Catholics. 8. James I ordered the clergy of the Church of England to read The Book of Sports from their pulpits in Lancashire and perhaps throughout England in 1618. James I was concerned that Puritans preaching in the county were insisting that Sunday be reserved exclusively for rest and study. Such prohibitions might drive the people toward Catholicism. The Book, which James wrote, read in part: “For when shall the common people have leave to exercise, if not upon the Sundays and holy days, seeing they must apply their labor and win their living in all working-days? …no lawful recreation shall be barred to our good people, which shall not tend to the breach of our aforesaid laws and canons of our Church.” So many of the clergy refused to read the Book from their pulpits that James I withdrew his order. 9. Gentlemen beyond London began to hire agents in London to send them letters containing news of the latest events in the Commons, at Court and abroad. These news letters were the precursors of the first newspapers, which began in the 1620s. [At first, the newspaper was called a "coranto" because it gave the current news]. 10. Fearing continued persecution from James I and lacking hope for change, two groups of Puritan Separatists fled England in 1620 for North America. The smaller of the two founded Plymouth Colony on Cape Cod Bay while the larger founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Spring 2014 MWH-1AS Charles I execution—Source A page 2 11. James I re-called Parliament in 1621 to discuss the future marriage of his son, Charles, to a Spanish princess. Parliament was outraged. If such a marriage occurred, would the heirs be brought up as Catholics? The marriage never took place but the suspicious relationship between king and Parliament outlived James, who died in 1625. 12. Under James I, Parliament met three times: from 16041611, briefly in 1614 before he dissolved it, and briefly again in 1621 before he dissolved it. In 1614 and 1621, Parliament was eager to discuss whether the Crown could raise funds without the consent of Parliament. 13. When England resumed war with Spain in 1624, Parliament distrusted James I and refused to adequately fund the war. Parliament’s refusal compelled Charles I, who succeeded his father James I in 1625, to levy discontinued taxes and subject English property owners to a “forced loan”. Charles I imprisoned property owners who refused these loans to the crown. To save money and keep a close eye on local politics, he also quartered troops in private homes. 14. Charles I married Henrietta Maria in 1625. Henrietta was the Catholic daughter of Henry IV of France, arousing suspicion among notable Protestants in England that Charles was more sympathetic to Catholics than Protestants and alarming Protestants that heirs to the throne might be Catholic. Every English King was the head of the Church of England, a very different church than the Roman Catholic Church. 15. “…as the King is the sacred & supreme Head of two Bodies, the one Spiritual, the other Secular: so, this high and royal Text contains in it two parts correspondent: The one Civil, which is a Counsel of State, or a politique caution; I counsel thee to keep the King’s commandment: the other Spiritual, which is a devout or religious reason...The zeal, and fervor of which Religion, if at any time it fall into a wane or declination, contempt or derision, portends evermore, the Ruin and desolation of that State and Kingdom, where, the service and worship of him who sits in heaven, is set at naught: and fills the world with terrible examples of God’s revenging Justice, and most ireful indignation.” Bishop Roger Maynwaring, in a sermon entitled Religion and Allegiance, 4 July 1627. Charles ordered the sermon published and distributed. http://oll.libertyfund.org/?option=com_staticxt&staticfile=show .php%3Ftitle=810&chapter=164703&layout=html&Itemid=27 Spring 2014 MWH-1AS Charles I execution—Source A page 3 16. Parliament drafted the Petition of Rights in 1628 and requested Charles I sign it. The Petition recited many principles from Magna Carta, including that there should be no forced loans or taxation without the consent of Parliament, that imprisonment without due cause and quartering troops in private homes exceeded the authority of the crown, and that martial law could not be used in times of peace. 17. Charles I accepted the Petition of Rights presented in 1628, but after further conflicts, he adjourned Parliament shortly after in 1629. Charles next convened Parliament in 1640. 18. Anglican Church Archbishop William Laud (appointed by and with the blessing of Charles I) attempted to force all churches in Scotland to use a prayer book nearly identical to the Anglican Book of Common Prayer in 1637. Accustomed to their own practice of Christianity and proud of their own liturgy and especially their independence, the Scots rebelled and declared war on Charles I. 19. Parliamentary leaders in the 1640s like Oliver Cromwell, Edward Coke, William Prynne, John Pym, John Hampden, Denzil Holles, Arthur Haselrig and William Strode, among others, were extremely capable leaders at a time when many Englishmen rejected absolute monarchy. 20. “Since the breach of the last Parliament, his majesty hath, by a new book of rates, very much increased the burden upon merchandise, and now tonnage and poundage, old and new impositions, are all taken by prerogative, without any grant in Parliament, or authority of law, as we conceive…Men’s goods are seized, their legal suits are stopped, and justice denied to those that desire to take the benefit of the law. The great sums of money received upon these impositions, intended for the guard of the seas, claimed and defended upon no ground but of public trust, for protection of merchants and defense of the ports, are dispersed to other uses, and a new tax raised for the same purposes.” John Pym, speech to Parliament, 17 April 1640 21. The Scots defeated the English army at the battle of Newburn in the summer of 1640. This defeat compelled Charles to reconvene Parliament in November 1640. Parliament promptly determined that it could not be adjourned without its own consent. 22. Charles I again requested Parliament raise funds for his army to suppress the Scots rebellion in 1641. Parliament preferred to become commander-in-chief of the army rather than entrust it to Charles I. Parliament refused Charles I request. Spring 2014 MWH-1AS Charles I execution—Source A page 4 23. Thomas Wentworth became lord deputy of Ireland in 1633 and began a series of reforms which alienated both the Protestant and Catholic ruling elites in Ireland. Wentworth challenged land deeds, confiscated Catholic lands, arbitrarily rejected juries and imposed substantial fines on local officials. Eventually Wentworth’s imperial attitude caught up with him—he had made too many enemies in Ireland. The House of Lords impeached Wentworth in late 1640 and executed him in May, 1641. 24. “Some of the expressions referred to were uttered in private, and I do protest against their being drawn to my injury in this place. If, my lords, words spoken to friends in familiar discourse, spoken at one’s table, spoken in one’s chamber, spoken in one’s sick bed, spoken, perhaps, to gain better reason, to gain one’s self more clear light and judgment by reasoning,—if these things shall be brought against a man as treason, this (under favor) takes away the comfort of all human society. By this means we shall be debarred from speaking—the principal joy and comfort of life—with wise and good men, to become wiser and better ourselves. If these things be strained to take away life, and honor, and all that is desirable, this will be a silent world! A city will become a hermitage, and sheep will be found among a crowd and press of people! No man will dare to impart his solitary thoughts or opinions to his friend and neighbor!” Thomas Wentworth, 13 April, 1641 before the House of Lords http://www.bartleby.com/268/3/9.html 25. Rumors circulated in January 1642 that Parliament might impeach Queen Henrietta Maria. Outraged, Charles barged into Parliament in January 1642 to arrest his Parliamentary opponents, but they escaped. In disgust, Charles I left London to raise his own army. The Parliament passed the Militia Ordinance of 1642 establishing Parliamentary control over county militias. 26. Charles I ultimately headquartered in Oxford and raised his army. After a series of indecisive battles, the Parliamentary Army crushed the Royalists at the Battle of Naseby in June 1645 and captured all the Royalists artillery and stores. Charles I's private papers fell into the hands of the Parliamentarians, revealing the full extent of his negotiations to bring over Irish Catholics to fight against Parliament, and his efforts to secure foreign mercenaries and money from abroad. 27. Charles I surrendered to the Army in 1648. While Parliamentary leaders spent fruitless months failing to negotiate a settlement with him, others allege that Charles was encouraging uprisings in England and Wales and an invasion from Scotland. Spring 2014 MWH-1AS Charles I execution—Source A page 5 28. On the morning of 6 December 1648 Colonel Thomas Pride and his soldiers stood outside the entrance to St Stephen's Chapel. As the Commons convened, Pride arrested 45 Members and excluded a further 186 whom the Army thought were unlikely to support its goal of punishing the King. These detentions became known as “Pride’s Purge” 29. After this military coup a further 86 Members left in protest. Pride's Purge left a 'Rump' (as it came to be called) of barely 200 Members. Among these, a determined clique unilaterally forced through an 'Act' on 6 January 1649, establishing a court to try Charles I for high treason ignoring the negative vote a few days before of the small number of peers still sitting in the Lords. 30. During the trial in Westminster Hall in 1649, Charles I disputed the authority of the court and refused to enter a plea. Regardless of the widespread opposition to the trial, a verdict of guilty was pushed through. The death warrant was signed by only 57 of the 159 commissioners of the high court originally established by the Rump. 31. “I stand more for the liberty of my people, than any here that come to be my pretended judges ... I do not come here as submitting to the Court. I will stand as much for the privilege of the House of Commons, rightly understood, as any man here whatsoever: I see no House of Lords here, that may constitute a Parliament ... Let me see a legal authority warranted by the Word of God, the Scriptures, or warranted by the constitutions of the Kingdom, and I will answer….a King cannot be tried by any superior jurisdiction on earth: but it is not my case alone, it is the freedom and the liberty of the people of England; and do you pretend what you will, I stand more for their liberties. For if power without law, may make laws, may alter the fundamental laws of the Kingdom, I do not know what subject he is in England that can be sure of his life, or anything that he calls his own….I never took up arms against the people, but for the laws .... It is the liberty of the people of England that I stand for.” Charles I, January, 1949, during his trial at Commons http://www.constitution.org/primarysources/charles.html 32. “The degree of the punishment, and the consequences of a crime, ought to be so contrived as to have the greatest possible effect on others, with the least possible pain to the delinquent. If there be any society in which this is not a fundamental principle, it is an unlawful society; for mankind, by their union, originally intended to subject themselves to the least evils possible.” Beccaria Spring 2014 MWH-1AS Charles I execution—Source A page 6