Design and Performance of Small Scale Sensory Consumer Tests

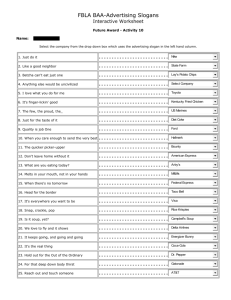

advertisement