Finding Common Ground: A Critical Review of Land Use and

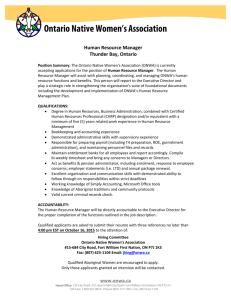

advertisement