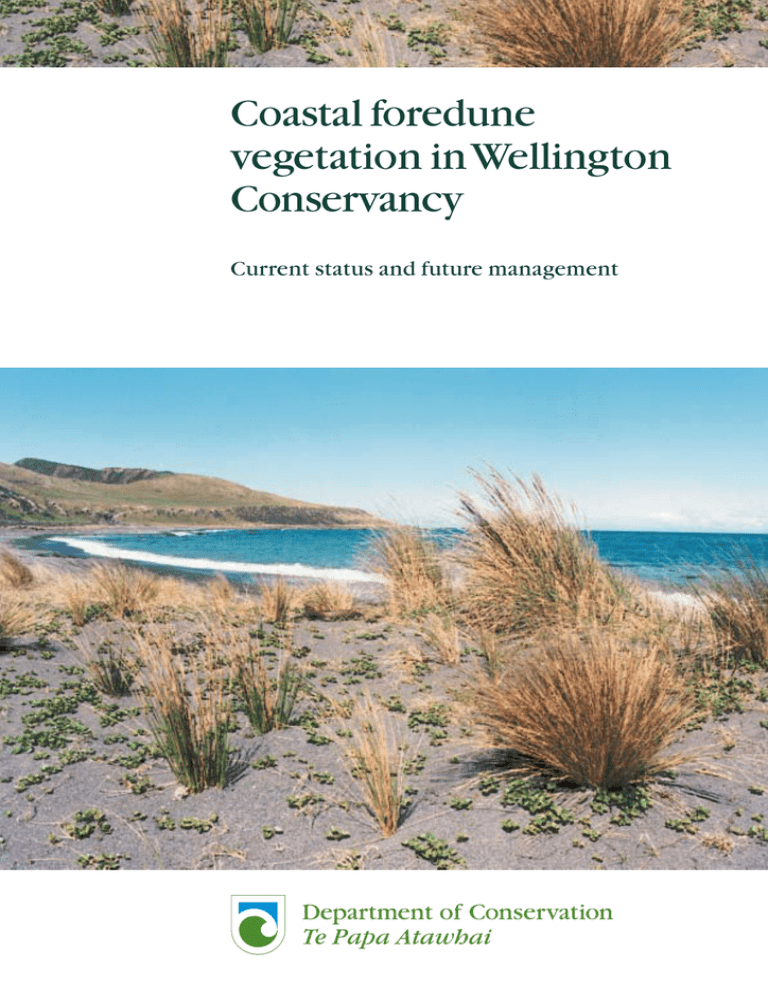

Coastal foredune vegetation in Wellington Conservancy

advertisement