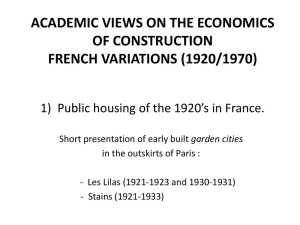

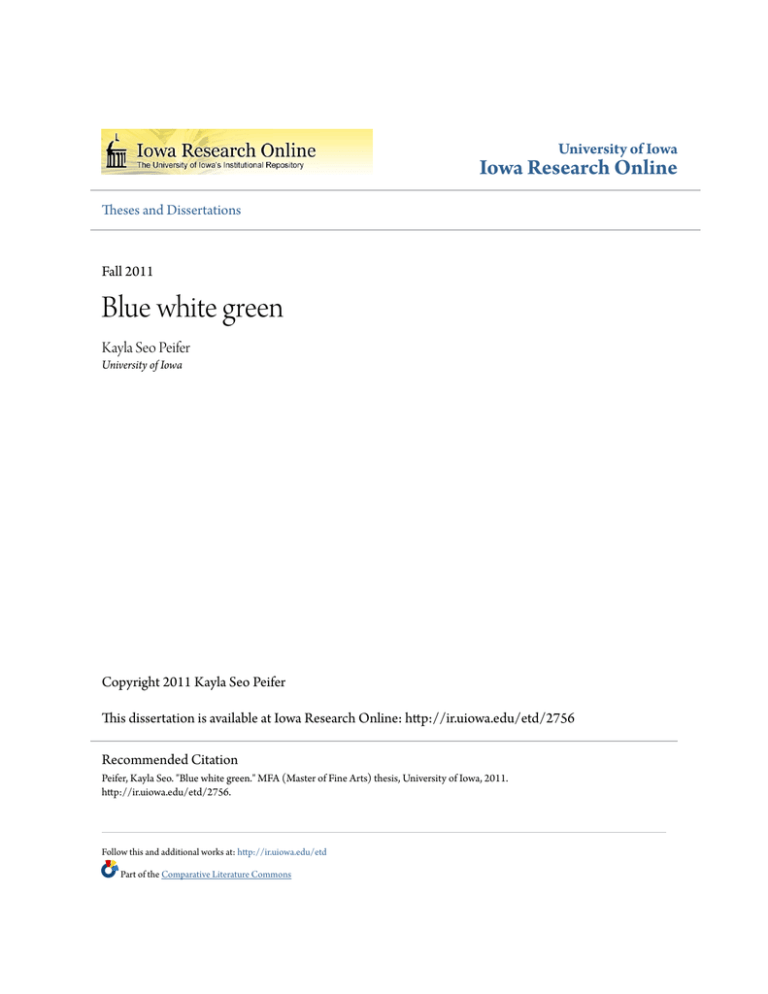

Blue white green - Iowa Research Online

advertisement